2

FIVE UNFORGETTABLE GAMES

LOYOLA 60, UC 58 (OT) MARCH 23, 1963, NCAA FINAL

The University of Cincinnati had won back-to-back national championships and was going for three in a row. UC was playing in its fifth consecutive Final Four, something no school had done to that point. The Bearcats blasted seventh-ranked Oregon 80-46 in the semifinals to set up their meeting with No. 3 Loyola (Illinois), the highest-scoring team in the country, in the 1963 NCAA title game.

No. 1-ranked UC was 26-1—its only loss coming at Wichita State, 65-64, in February.

The coaches stayed up until 4 a.m. preparing for Loyola. Tony Yates, the team captain and starting guard, became sick the afternoon of the game and was taken to Methodist Hospital in Louisville for treatment. About 15 minutes before tipoff, Yates joined his teammates on the court.

Still, it didn’t look like coach Ed Jucker’s team was going to have to sweat it out. The Bearcats were ahead 45-30 with 14 minutes remaining.

“At that point, I was hoping we would lose respectably,” Loyola All-American Jerry Harkness told The Cincinnati Post in 1987.

But UC players George Wilson and Tom Thacker got in foul trouble, and Loyola managed to crawl back into the game, which was played at Louisville’s Freedom Hall. In the final 10 minutes, UC went into a controlled offense and tried to run time off the clock.

The strategy seemed to backfire. The Bearcats had just one field goal in the final 14 minutes of regulation. Yates got in foul trouble. So did leading scorer Ron Bonham.

Cincinnati was ahead by one point when Harkness fouled Larry Shingleton with 12 seconds left in regulation. Loyola called a timeout. Jucker had plenty to tell his players, too.

“To this day, I couldn’t tell you one word he said,” Shingleton said. “I was on the bench praying.”

Shingleton swished the first free throw. He turned around and looked at Yates, who had a big grin on his face. UC led 54-52.

But Shingleton missed the next foul shot; the ball bounced off the rim to the right. Loyola’s Vic Rouse rebounded it, threw the ball to Ron Miller, who took several steps according to players from both teams (but wasn’t called for traveling) and passed the ball to Harkness, who went in for a layup that sent the game into overtime.

Loyola then won 60-58 on a rebound basket by the six-foot-six Rouse with one second left in the extra period. The Ramblers only shot 27.4 percent from the field; UC shot 49 percent.

“At halftime, we had Loyola completely under control,” Bonham said. “The guy guarding me said, ‘You’ve got one helluva team.’ It just wasn’t to be. You never get over that. We could’ve played them another 50 times and beaten them. I had 22 points and I don’t think I took a shot the last 10 minutes of the game.”

The 1963 NCAA runner-up trophy came home to Cincinnati by bus without much fanfare. The trophy is now proudly displayed in the Richard E. Lindner Center, the centerpiece of the University’s $105 million Varsity Village, which opened in 2006. (Photo by University of Cincinnati/Sports Information)

More than 35 years later, Shingleton was at a hardware store, signing a credit card slip at the cash register when the woman checking him out noticed the NCAA championship ring he was wearing and asked what it was for. Shingleton told her.

Then the man standing next to Shingleton in line blurted out, “Yeah, if he’d have made that damn free throw in ’63, we would’ve won three in a row.”

“Invariably, somewhere every year, somebody will say, ‘Are you the guy who missed the free throw?’ People often become infamous, if you will, on the basis of what they fail to do, not what they did do,” Shingleton said.

“I know one thing: I didn’t choke. I didn’t freeze. I swished the first one. The reason I missed, the ball rolled off the wrong fingers on my left hand. I’ve never said (the loss) was my fault. I always said, ‘Boy, I had a hell of an opportunity to be the youngest senator from the state of Ohio.’ If I had made that free throw, we would’ve been the only team in history—at that point—to win three in a row.”

That was Shingleton’s last organized basketball game.

There is a picture of Shingleton missing the foul shot, with the scoreboard partially visible. Since 1964, he has sent out roughly 50 cards, often including a copy of the photo, to what he calls members of the “Woulda/Coulda/Shoulda Been a Hero Club.”

Georgetown guard Fred Brown got one of Shingleton’s notes of encouragement after he threw a pass right to North Carolina’s James Worthy at the end of the 1982 NCAA championship basketball game. Michigan’s Chris Webber got one after he called a timeout at the end of the 1993 NCAA final against North Carolina (the Wolverines were out of timeouts and were called for a technical foul). Florida State kicker Xavier Beitia got one in 2002 after missing a 43-yard field goal (wide left) as time expired in a 28-27 loss to rival Miami (Florida).

“What I always say is there’s life after missed free throws, missed field goals or whatever,” Shingleton said.

In 2003, he was with his mother and grandson having lunch at a Ruby Tuesday in Cincinnati. On the television, as part of Black History Month, was a replay of the 1963 NCAA final between UC and Loyola.

Shingleton couldn’t help but watch. “You know,” he said, “I missed that free throw again on the instant replay.”

When he got home that day, he called Yates.

“All these years I’ve been taking the flak for losing the game,” he told his former teammate. “But damn it, Thacker didn’t box out!”

UC 75, BRADLEY 73 (7OT) DECEMBER 21, 1981

No Division I game in NCAA history has lasted longer. Seven overtimes. Seventy-five minutes of playing time. Three hours, 15 minutes of high drama.

“My heart was racing the entire game,” UC’s Jelly Jones said afterward.

There was no shot clock, so in the overtime periods, the teams mostly held the ball. During the third overtime, neither team scored. No team got more than four points in any overtime period.

The unlikely hero would turn out to be Doug Schloemer, a senior reserve and former Mr. Basketball in Kentucky who averaged 4.8 points that season.

Schloemer had a key offensive rebound in the sixth OT, then hit a jumper to tie the game at 73 and send it to a seventh extra period.

Neither team had scored in the seventh OT. UC had the ball in the final seconds and called timeout. Point guard Junior Johnson was supposed to penetrate to the basket. If nobody picked him up, he was going to go all the way to the goal. If the defense collapsed on him, he was expected to pitch the ball out to one of the wings. Bobby Austin would be on the right side, Schloemer on the left.

Well, Johnson was swarmed and Austin was being shadowed. The ball came out to Schloemer, who was about 18 feet out, foul line extended. He caught it and launched the shot with defender Voise Winters running at him hard.

“I don’t know how he missed it,” Schloemer said. “He came crashing by me. It’s one of those things, when you let a shot go, you know it’s in. It felt good.”

There was one second left. After a timeout, Bradley inbounded the ball and got off a 20-foot attempt that bounced off the rim.

“My body’s tired,” Bearcats forward Kevin Gaffney said after the game. “I feel like an old man. I don’t know how old people feel, but if it’s like this, it’s a terrible feeling.”

The six-foot-five Schloemer, from Holmes High School in Covington, Kentucky, finished with just six points but was three of three from the field.

“I was soaking wet,” UC coach Ed Badger recalled. “I was exhausted. I was getting tired of climbing up and down on that (raised) floor (at old Bradley Arena). It was a long, long game. It was really fun when you think about it now.”

“I played 68 minutes,” Johnson said. “I played the last 40 with four fouls. Every pass, every dribble, every single thing was so intense. That’s what you live for. I was mentally and physically drained, but you’re just working off adrenaline.”

The Bearcats were 7-1 after their final game before Christmas. Bradley would go on to win the 1982 National Invitation Tournament.

“I would say that was one of the highlights of an otherwise pretty mediocre career,” Schloemer said with a laugh.

KENTUCKY 24, UC 11 DECEMBER 20, 1983

Shortly after Tony Yates was hired as UC’s head coach in April 1983, he had a meeting with Athletic Director Mike McGee to review the upcoming schedule.

McGee told Yates he had worked out a three-game contract to play perennial power Kentucky—and the series would begin that December in what would be Yates’s eighth game as a Division I head coach.

“That day I told Mike I was going to hold the ball against them,” Yates said. “I don’t think he took me seriously.”

The Bearcats came into the game at Riverfront Coliseum with a 1-6 record, a starting center (Mark Dorris) who was just six foot six and only one player (Dorris) who would average in double figures that season.

Unbeaten Kentucky came in ranked No. 2 in the country and had a front line that consisted of future NBA players Melvin Turpin (6-11), Sam Bowie (7-1) and Kenny Walker (6-8). The Wildcats were favored by 18 points. The game was nationally televised on ESPN.

“I thought the only way we had a chance to win, was to do what we did,” Yates said.

Cincinnati had worked on its “delay” game a little in practice, but there was no hint of Yates’s strategy until game day. It was then, in the locker room, he told the players his plan: The Bearcats would hold the ball on every possession until they had a chance for a layup. At the time, there was no shot clock forcing teams to shoot within a certain number of seconds.

“We just kind of looked around at each other (and thought), ‘You’ve got to be kidding?’” Luther Tiggs said. “We’re going to freeze the ball on national television? This man has lost his mind.”

Yates wasn’t sure how his players felt about his strategy, but he knew they’d carry it out as best they could.

“And they did it to the letter,” he said.

Kentucky won the opening tipoff and immediately lobbed an alley-oop pass to Bowie near the basket. He was fouled. He missed the first free throw and made the second.

The Bearcats then passed the ball 22 times on their first possession. By the seventh pass, there were boos from the crowd. Dorris hit a jumper just above the foul line for a 2-1 UC lead. Kentucky missed its next shot, and UC went into a four-corner spread, normally used to run time off the clock at the end of games.

UC took only five first-half shots and trailed 11-7 at intermission. At one point, the Bearcats held the ball for seven minutes, 22 seconds.

Kentucky ended up winning 24-11.

Yates could hear fans booing throughout the game. The crowd would start chanting: “Bor-ing.” Though Wildcats coach Joe B. Hall never said anything to Yates, he did tell the media afterward that he’d never consider such a strategy.

“I would not have the guts to do that before our home fans,” Hall said that night. “The real feeling I have is that our fans were somewhat exploited. Some of them bought Cincinnati season tickets to see this game.”

Cincinnati scored its fewest amount of points since 1930; Kentucky totaled its fewest since 1937. Hall made it clear he would not favor resuming the series with the Bearcats after the three-game contract expired.

“We would like to continue this series,” McGee was quoted as saying in The Cincinnati Enquirer. “But we’re not going to go begging. And if that’s the way it is, that’s the way it is.”

Yates said he got several letters from all over the country after that game, almost all in support. Some coaches wrote and told him, “You did what you had to do to win the game.”

A year later, in December 1984, the Bearcats went to Lexington to play in the University of Kentucky Invitational. The day before the tournament started, there was a banquet attended by fans.

All the coaches spoke. When it was Yates’s turn, he stood up and said: “Folks, I just want to prepare you for tomorrow night and get you warmed up. So on the count of three, I want you all to stand up and boo me right now.

“One . . . two . . . three . . . ”

Sure enough, the crowd booed. Yates laughed.

“I just kind of tried to take the edge off,” he said.

UC 66, MINNESOTA 64 NOVEMBER 25, 1989

Steve Sanders was a wide receiver from Cleveland, Ohio, who played four years for the University of Cincinnati football team. But that’s not how he will forever be remembered on the UC campus.

This is what made Sanders part of Bearcats basketball history: It was his three-pointer from the corner as time ran out that gave Cincinnati a 66-64 victory over 20th-ranked Minnesota in the first regular-season game at Shoemaker Center—and the first game of the Bob Huggins era.

Here is what led up to November 25, 1989 . . .

Sanders’s last football season was 1988. He knew he was coming back to UC for a fifth year to try to complete requirements for his degree. In the spring 1989, Sanders was playing intramural basketball and caught the eye of assistant basketball coach Larry Harrison. Harrison, who was on the lookout for players, asked News Record reporter Branson Wright about Sanders and another football player, Roosevelt Mukes. “Steve was our nemesis in intramural basketball,” Wright says now. Sanders played pickup games every off season with UC basketball players, felt he held his own, and often wondered whether he could play Division I basketball.

The next fall, Sanders joined the basketball team for preseason conditioning, then had second thoughts.

“That was the hardest thing I ever did in my life,” Sanders said. “I talked to Coach Harrison and said, ‘I don’t know if I can do this.’ We just ran so much. I actually stopped for about two weeks.”

When practices officially started, UC held walk-on tryouts. The six-foot-two Sanders and the five-foot-ten Mukes, who at the time was the school’s all-time leading wide receiver, both showed up.

“Coming in, I didn’t really expect to play a lot,” Sanders said. “I thought maybe I could play five or 10 minutes a game and just enjoy the experience. But as time went on, I started feeling more and more comfortable.”

Huggins was beginning to assert himself as the Bearcats coach and certainly grabbed the attention of the players.

“He was a maniac,” Sanders said. “The yelling and the screaming didn’t bother me. I came from a football background, and that’s all football coaches do is yell and scream. But practice was so intense for three-and-a-half hours. He never let us cheat ourselves. I was in the best shape of my life playing basketball.”

The Bearcats only had eight scholarship players. By the first game, Sanders was in the starting backcourt with Andre Tate.

“The whole time leading up to the Minnesota game, he never let us think that we weren’t good enough to win,” Sanders said of Huggins. “We had an awful lot of confidence, which he gave us. And the coaching staff did a great job with the scouting report. Everything he said that they would do during the game, they did.”

Sanders, who would average 7.0 points and 2.5 rebounds for the season, had four points all game. Until the very end.

UC led by one with 30 seconds left. Lou Banks fouled Willie Burton off the ball on an inbounds pass, and Burton made two free throws.

Minnesota was ahead 64-63—its first lead in the second half. The Bearcats brought the ball up past midcourt and called their final timeout.

Cincinnati worked the ball around, but when Keith Starks tried to hit Tate cutting across the foul line, the ball was stolen by Minnesota’s Kevin Lynch, who dribbled down the sideline in front of the scorer’s table. Lynch picked up his dribble right in the front of the Minnesota bench and started falling out of bounds. He tried to throw the ball off Tate and missed, and it bounced all the way back toward the UC basket and went out of bounds on the baseline with eight-tenths of a second remaining.

The Golden Gophers called a timeout.

The first thing Huggins told his players was, “You guys are going to win this basketball game.”

As the huddle broke, Huggins grabbed Sanders by the arm and said, “Steve, if they can’t get it inside, you have to break around, because Andre’s going to throw you the ball.”

Tate had to inbound the ball against seven-footer Bob Martin. The play was designed for Tate to lob it toward the basket. Banks was covered when he cut inside. By the time Levertis Robinson broke free into the middle of the paint, Tate was looking toward his last option.

Sanders had broken toward the ball, faked back, then went to the corner in front of the UC bench. Tate delivered a short bounce pass. Sanders caught it and shot it from about 20 feet out over Martin, his first three-point attempt of the night and the Bearcats’ only three-point field goal in the game.

Swish.

The arena erupted.

“It felt perfect,” Sanders said. “It felt like I just placed the ball into the basket. It had to go in. I saw it and when it went in, I was so happy. There was so much energy flowing through my body I cannot explain. I jumped up and down and ran, and they chased me and caught me. They dived on top of me. They picked me up and then I got down and ran across the court and up into the stands. Everybody was off the court but me. I was still running around in the stands. Then I ran down back through the court again. When I finally got in the locker room, I was so hyped and excited, I just had to go lay down on the floor in the shower. . . . It was truly amazing.”

Later, Sanders was talking to Harrison.

“You know, you just went down in UC basketball history,” the assistant coach said.

“Coach, in two weeks, no one will remember this shot,” Sanders told him.

He couldn’t have been more wrong.

UC 77, DUKE 75 NOVEMBER 28, 1998

There had been so many heartaches for the University of Cincinnati during Melvin Levett’s career.

Miles Simon’s buzzer-beating 65-foot bank shot that handed No. 13 Arizona a 79-76 victory in February 1996. Lenny Brown’s last-second jumper that gave Xavier a 71-69 upset over the No. 1-ranked Bearcats in November 1996. Top-ranked Kansas coming back from 16 points down to beat UC 72-65 in Chicago just over a week later. The 1998 NCAA Tournament loss to West Virginia on Jarrod West’s halfcourt heave with 0.8 seconds to play.

That is the context of the championship game of the 1998 Great Alaska Shootout.

No. 1 Duke vs. No. 15 Cincinnati. National TV. Midnight tipoff.

Fast forward to the end.

The Bearcats were ahead 74-73 when Pete Mickeal went to the foul line with 42 seconds left, but Mickeal missed both free throws. Duke missed two shots on its possession, and UC rebounded. Alvin Mitchell was quickly fouled with 13 seconds remaining. Mitchell missed his first foul shot, then made the second. UC led 75-73.

After a UC timeout, Duke guard William Avery hit a running jumper from the baseline over Kenyon Martin to tie the game with three seconds to play.

“We were always in that position, playing a big school, and somehow, someway, we always let it slip away,” Levett said. “We knew this was our moment.”

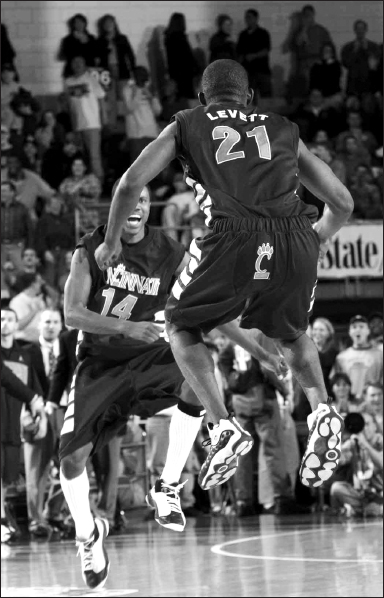

Melvin Levett (21) and Alvin Mitchell (14) leap in celebration of Levett’s game-winning dunk against Duke in the 1998 Great Alaska Shootout. Levett was named by Slam magazine in 2001 as one of the 50 greatest dunkers of all time. (Jim Lavrakas/ Anchorage Daily News)

The Bearcats called a timeout, and without hesitation Huggins drew up a play that the team had gone over in practice—though not often with success.

“Sometimes you’d think, ‘What are we doing this for?’ Because when we ran it in practice, it didn’t go smoothly, or we didn’t beat the buzzer,” Levett said. “But this time it was like destiny.”

Ryan Fletcher took the ball out of bounds from under Duke’s basket. He sailed a long pass to Martin, standing at the top of the three-point arc near UC’s basket. Martin jumped, caught the ball, immediately turned to his left, and—before he landed back on the ground—passed to Levett, who was streaking toward the basket on the right side. Levett snagged the ball on the run and went straight up.

“I didn’t want to lay it up because you’ve seen guys in those situations blow the layup,” Levett said. “I wanted to leave no doubt.”

He jumped . . . and dunked (hard) . . . to complete one of the most memorable baskets in Bearcats history.

“Everything flowed. It was unbelievable,” Levett said.

“You’d pray sometimes . . . that maybe you could have that moment. I just burst into tears. I had to be calmed down during the timeout before they came out and ran their last play. I was losing it. I kind of got caught up in the moment.”

What is almost forgotten is that Duke, with one second on the clock, almost tied it again. Shane Battier threw a full-court pass that got knocked back to Avery, who nailed a 14-foot bank shot—clearly after the final buzzer sounded.

“It was more than just us winning that game,” Levett said. “It was for Cincinnati, for our school, and for all the teams that didn’t win before.”