3

JOHN WIETHE ERA (1946-1952)

We begin now in the 1940s.

Though the University of Cincinnati basketball program officially started in 1901, it was in the latter part of the ’40s that the Bearcats first won 20 games, first averaged more than 50 points a game, first achieved a national ranking, first hired a full-time coach, and first had a 1,000-point scorer.

Most important, however, expectations were forever changed.

FOOD, GLORIOUS FOOD

More than 40 years before a driven and intense 35-year-old coach named Bob Huggins arrived in Clifton, the Bearcats were led by a man named John “Socko” Wiethe, who was equally known for his intensity and hatred of losing.

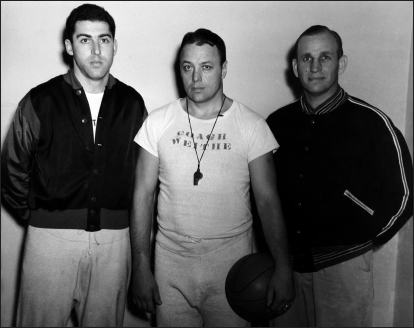

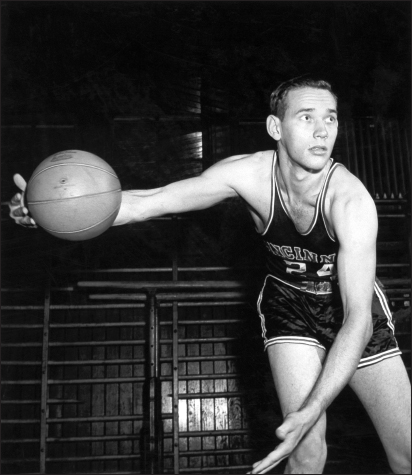

John Wiethe (center) led UC to a 106-47 record in six seasons. (Photo by University of Cincinnati/Sports Information)

Wiethe, a Xavier University graduate who attended UC’s College of Law, had a football background, having been an All-NFL guard for the Detroit Lions. He also played semi-pro baseball, pro basketball in Fort Wayne, and was an American Association umpire one year. Wiethe was a UC football team assistant coach before he took over the basketball team in 1946.

He had what could be considered an unusual way of expressing his dissatisfaction with losing to his players. He hit them where it counted—in their stomachs.

When UC played on the road and won, Wiethe would take his players out for steak dinner. When they lost? He’d give the student manager a five-dollar bill and tell him to go get 10 half-dollars. Then he’d give each player 50 cents to go buy a hamburger.

That went on until Athletic Director Chick Mileham went on a few road trips with the team, saw what was happening, and put an end to it.

SWITCHING SPORTS

Ray Penno started his athletic career at UC as a basketball player but ended up in another sport.

How did that happen?

Mileham saw Penno when he led Western Hills High School past Elder for the 1944 city league championship in Cincinnati. Mileham asked Penno if he wanted to play basketball at UC.

“Not really,” Penno told him.

“All my friends were going into the service,” he said. “It sounds corny, but I wanted to get in as soon as I could. But I was only 17.”

Mileham told Penno that he could play one year with the Bearcats, then join the military. Which is what he did. He started every game of the 1944-45 season and was the team’s No. 4 scorer with a 4.0 average.

UC closed its season with a 65-35 loss to Kentucky. The day after the game, Penno signed up with the U.S. Army and spent the next two years in The Philippines.

He returned to Cincinnati just in time for the end of the 1946-47 season. By then, the Bearcats had a new basketball coach: John Wiethe. Just before the final game of the season, Penno showed up on campus and introduced himself to Wiethe.

“Go down and get a uniform,” the coach said.

Penno didn’t want to, but he relented. He played maybe a minute in a 61-51 victory over Butler. In the locker room afterward, Wiethe introduced Penno to Ray Nolting, UC’s football coach. “We’d like you to come out and play end on the football team,” Nolting said.

Penno weighed over 200 pounds, about 30 more than when he first played basketball at UC. But, he had not played a down of high school football.

“I wouldn’t even know how to put on the uniform,” he told Nolting.

He got the hang of it quickly and played three years for the football team, including on the 1949 Glass Bowl team for coach Sid Gillman. He started five games in his football career.

“I just fell in love with football,” Penno said.

A DIFFERENT KIND OF START

Dick Dallmer was the second player in University of Cincinnati history to score 1,000 points—Bill Westerfeld was the first—and when Dallmer graduated in 1950, he was the Bearcats’ all-time leading scorer. He was also the first Bearcat to earn All-America honors. All of which are some pretty nice accomplishments for a guy who never played high school basketball—and, in fact, was cut from his team as a sophomore and junior.

Dallmer grew up in Hamilton, Ohio, and graduated from high school in 1942. Like many of his peers, he immediately reported to the military, joining the U.S. Army.

Dallmer was among the soldiers who landed on Normandy in France in June 1944 during World War II. Two months later, he was moved to the port city of LeHavre, France. At about 8 o’clock one night, he was walking through a path of rubble—the streets had been blown up—when he saw a large building with a hole in the roof. He noticed the lights were on and thought he heard balls bouncing.

Sure enough, some GIs were playing basketball and invited Dallmer to join in. He took off his boots and played in stocking feet. He went back the next night. And the next. After the fourth night of playing, he was approached by the master sergeant, who told Dallmer he was being transferred to headquarters in Lille, France, in the morning.

“Why?” Dallmer asked. He was told that the commanding general was a West Point graduate who wanted the best basketball team in the area.

Dallmer’s team won the section title and played in Paris for the U.S. Army championship of Europe. He had left high school six feet tall, 160 pounds. Two years later, he was 6-3, 190 and holding his own against former college and pro players.

Dallmer was discharged in November 1945. He signed up for classes at UC, but it was too late to play basketball for the Bearcats that season. That winter, he played with Champion Paper Company of Hamilton, which won the state industrial championship. Dallmer was named MVP of the league and had tryout offers at Kentucky and Tennessee. Wiethe was given Dallmer’s name, invited him to try out in the summer of ’46, then offered him a scholarship.

“That’s how I got started at UC,” Dallmer said. “Now that’s a different story.”

Dallmer was an Associated Press honorable mention All-American in 1948 and ’49 and was third-team All-America in 1950. He finished his career with 1,098 points.

ROCKY RELATIONSHIP

Cincinnati native Ralph Richter was an Elder guy. So naturally, coming out of the Catholic high school on Cincinnati’s west side, he figured he’d go to Xavier University, the Jesuit college across town from UC.

After serving two years in the navy, Richter returned to Cincinnati in the fall of 1946 and went to XU to talk to coach Lew Hirt about joining the team. Hirt—“a Hamilton guy”—said Richter could come over for a tryout. But there was no scholarship offer.

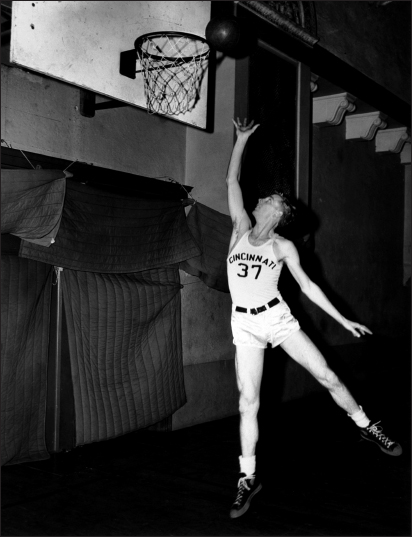

Ralph Richter was Cincinnati’s leading scorer in 1948-49, averaging 16.4 points a game for the 23-5 Bearcats. (Photo by University of Cincinnati/Sports Information)

“I knew I was in bad shape,” Richter said. “He kind of favored the boys from Hamilton and Middletown. So I talked to my high school coach, Mr. Walter Bartlett, and he said, ‘I think UC’s trying to build up a team.’”

As it turns out, Wiethe had coached at Roger Bacon High School at the same time Richter played at Elder. But when Richter approached Wiethe about playing for the Bearcats, the coach acted as if he knew nothing about Richter.

“Did you ever play?” Wiethe asked.

“I played some in the service,” Richter told him. “I averaged about 25 points.”

Richter said that Wiethe then turned to football coach Ray Nolting and said, “Listen to this clown over here.”

That was the start of what would be a rocky relationship between UC’s third 1,000-point scorer and his character of a coach.

The six-foot-four Richter led Cincinnati in scoring in 1947-48 and 1948-49. But he and Wiethe never did see eye to eye.

‘HE WAS A DIFFERENT BREED’

This was an interesting postponement of a game.

The Bearcats were scheduled to play the University of Miami (Florida) in the Orange Bowl in Miami on February 6, 1947.

But it got so cold and windy—yes, that cold in Miami—that the basketball game was postponed until the next day and played in a Miami high school gym. The Hurricanes won 57-54 in the final seconds, and Wiethe was none too happy.

UC flew home that night and landed at the airport in Northern Kentucky. A school bus was waiting for the team.

Wiethe jumped in the bus and rode it back to campus. Alone. He gave the players bus fare, and they had to wait until six in the morning when the buses started running to leave the airport. Their bus stopped at every stop all the way into Cincinnati.

“We said many times he was nuts,” Dallmer said. “He was a different breed. And he took pride in that.”

TRIVIA QUESTION

Who scored the first basket ever at Cincinnati Gardens?

It was Richter, who hit a five-foot hook shot over a Butler defender on February 22, 1949. UC won 49-41.

“I just happened to be the guy who got the ball,” he said. “I was very pleased about it, though.”

Turns out it was Richter’s only field goal of the game. He finished with six points.

NOT ON SAME PAGE

Richter never warmed to Wiethe. “Very difficult to get along with at times,” Richter said of his coach. “The longer you were there, the more difficult it became.”

In his fourth year in college in 1949-50, Richter was accepted to UC’s medical school. He did not plan to play his senior year, but after a meeting with Wiethe, he agreed to participate in only Cincinnati’s home games.

“That worked out for a while—until we finally had an away game,” Richter said.

The 12th-ranked Bearcats had a Monday night game at No. 14 Western Kentucky on January 16. On Sunday, Richter received a phone call from a man who said he was a pilot; Wiethe—without telling Richter—had arranged for a private two-seat airplane to fly Richter to Bowling Green, Kentucky, from Lunken Airport at 4 p.m. the day of the game.

“I had classes until 5 o’clock,” Richter said. “I didn’t go because I couldn’t miss that much school and I wasn’t too anxious to fly to Bowling Green, Kentucky, at night in a two-seat airplane.”

He sent Wiethe a telegram saying he couldn’t make it. The players told Richter that Wiethe “hit the ceiling” after he got the telegram. Western Kentucky won 84-59. Afterward, WKU coach Ed Dibble brought a basket of apples to the Bearcats in their locker room. Wiethe took one and slammed it off the wall.

“After that,” Richter said, “things weren’t too smooth.”

Richter averaged 8.7 points coming off the bench that season. He went on to become an orthopedic surgeon in Cincinnati—and even worked for the Cincinnati Bengals in the 1970s.

HEADS UP

Dallmer remembers the tension between Richter and Wiethe. One day, the Bearcats were running a figure-8 drill to warm up at the beginning of practice. Wiethe watched from a chair.

After about 15 minutes, a panting Richter told Dallmer: “Next time I get the ball, I’m going to sail it over his head where he’s sitting.”

“Sure enough, Ralph did it,” Dallmer said.

“Yeah, I missed him,” Richter added.

WARMS YOUR HEART, DOESN’T IT?

Richter and Wiethe did have their nice moments together. Well, maybe one.

When UC beat St. Francis (New York) 91-62 on February 18, 1949, Richter scored 38 points and established a UC record for single-season scoring. After the game, Wiethe walked by and said, “Pretty hot, huh Slim?” Then he walked away.

“That was the only compliment I got in four years,” Richter said.

He was Cincinnati’s No. 3 all-time scorer (1,053 points) when his career ended—behind only Dallmer and Westerfeld.

UH, SURE, I’M A CENTER

Jim Holstein was not the first UC player drafted into professional basketball, but he was the first to play in the National Basketball Association, spending 1952-55 with the Minneapolis Lakers and 1955-56 with Fort Wayne.

But he had to lie to get on the court to start his collegiate career.

Holstein was a guard for a Hamilton Catholic High School team that was state runner-up his senior year. UC offered him a scholarship.

When he arrived on campus in 1949, Holstein realized veteran guards Dick Dallmer and Ralph Richter were back for their senior years. Forwards Jack Laub and Al Rubenstein also returned. However, center Bill Westerfeld had graduated.

Wiethe asked Holstein if he had ever played center. Seeing that it was the only position available, Holstein fibbed and said, “Yeah, I played inside occasionally.”

In fact, he had never played inside.

The first day of practice, Wiethe put Holstein in at center. And because he had more of a scorer’s mentality, almost every time he got the ball, he shot it.

After practice, Wiethe called over Holstein. “I can’t use you at center because you shoot the ball all the time,” the coach said.

Holstein pleaded for another chance. The next day, he started passing the ball—and he was back as the team’s center.

“He saw I could play that part of the game, too,” Holstein said.

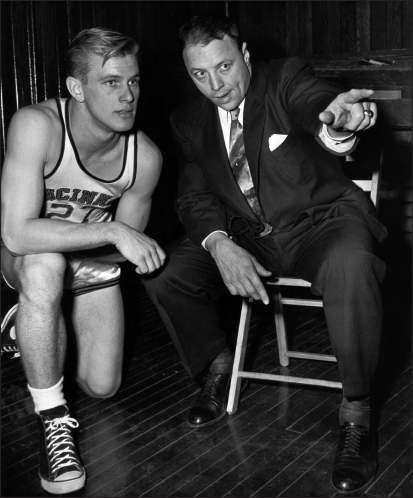

Jim Holstein (left) averaged 15.7 points and 12 rebounds in 1951-52, John Wiethe’s last season as UC’s coach. (Photo by University of Cincinnati/Sports Information)

The centers in the Mid-American Conference at the time were around 6-5 and 6-6. Holstein was 6-3 and able to drive by most defenders.

“I’m not sure I was quick enough to stay with the smaller guys,” he said. “Staying with the big guys was a snap. I loved center. I enjoyed the physical part of it. It just took time to get used to.”

After his college career, Wiethe recommended Holstein to the Lakers, with whom he went back to playing guard.

EARLY CHALLENGE

The third game of Holstein’s college career, he went up against Kansas’s two-time consensus first-team All-American Clyde Lovellette, who was six foot nine—six inches taller than Holstein. The two guarded each other all night.

UC would win 56-54 at the Cincinnati Gardens on December 15, 1949, and for Holstein, it was a memorable outing.

“I don’t recall how many points I got, but I held him to 15 points—and eight of them were free throws,” he said. “I’ve got a picture (from the game) on my wall.”

Holstein finished with 19 points. Afterward, Kansas coach Phog Allen did a fair amount of complaining about the referees.

GOING TOE TO TOE

Joe Luchi had served in the military and was older than most of his teammates. “But what a competitor,” Holstein said. “He really came after you. He was about six feet tall, but he was all man.”

Wiethe would sometimes play half-court games with the team during practice. One day, Wiethe hit Luchi, and Luchi went after his coach.

“All of a sudden, Joe was decked on the floor; John punched him good,” Holstein said. “So we jumped on Joe and held him and said, ‘Now, stop it, he’s going to kill you.’ They were punching each other while we were scrimmaging.”

They didn’t call the coach “Socko” for nothing.

WHAT ABOUT OUR REPUTATION?

UC played Long Island University at Madison Square Garden in New York on a Thursday night in February 1950. The Bearcats had a Saturday game scheduled against La Salle in Philadelphia.

When the team left New York on Friday morning, a student manager accidentally left his bag at the Bearcats’ hotel.

The good news for the manager was that Wiethe had stayed in New York to scout high school players that Friday night. An assistant coach called back and asked Wiethe to retrieve the bag from the hotel.

That was also bad news for the manager.

The UC team was in the lobby of its Philadelphia hotel when Wiethe arrived Saturday afternoon. As soon as Wiethe walked in, he threw the manager’s bag across the hotel’s tile lobby floor and smack into a wall on the other side.

The manager stood still. Wiethe was steaming.

“Damn you,” the coach said. “We had a good reputation up there, we were well behaved—and you’ve got two of the hotel towels in your handbag!”

“All I wanted was a souvenir,” the manager said.

The whole team cracked up.

INNER CONFLICT

The night of March 3, 1950, Wiethe didn’t know what to feed his players. Remember, he made sure they ate better when they won.

The Bearcats played in Cleveland against Western Reserve, which was coached by Wiethe’s friend Michael “Mo” Scarry, also a former NFL player. Well, UC was having its way with Western Reserve and nearing the 100-point plateau.

Though Wiethe loved to win, he didn’t want to embarrass an old pal. So as the final minute ticked away, he didn’t want UC to score anymore. The players, however, had other ideas. No Cincinnati team had ever scored 100 points in a game. So in the final seconds, one of the Bearcats called timeout. The players decided to let Western Reserve score, then they’d go down and try to get past the century mark.

Which they did. Don Huffner made the last three UC baskets.

Final score: Cincinnati 101, Western Reserve 58. The Bearcats finished 10-0 in the Mid-American Conference.

No matter. Wiethe was furious. He came into the locker room and scolded his players.

“That’s the only friend I have in the coaching business, and look what we did to him!” Wiethe yelled. “I don’t know whether to give you steak or hamburger.”

Interestingly, Scarry became the line coach of the UC football team in 1956.

CHANGE OF HEART

Bill Lammert had scholarship offers from UC and Xavier coming out of Roger Bacon High School, and he chose XU.

The summer after his senior year at Roger Bacon, Lammert was all set to become a Musketeer—even though he considered coach Lew Hirt’s deliberate style of play to be rather boring.

Wiethe held open gym for local high school players in the off season at UC, and even though Lammert had committed to Xavier, Wiethe welcomed him to the UC campus for pickup games. As the summer wore on, Lammert decided he was more comfortable with Wiethe’s up-tempo style. Two weeks before classes were to begin at Xavier, Lammert called Hirt to tell him he had changed his mind and was becoming a Bearcat. “He really reamed me out,” Lammert said.

He remembers calling from the southernmost phone booth in UC’s student union. And despite making numerous calls from the building during his college career, Lammert never returned to that same booth.

Here’s the kicker: Hirt never would have coached Lammert. He retired before the start of the 1951-52 season and was replaced by assistant Ned Wulk, whose teams played a completely different style.

“I guess if I had known Ned Wulk was going to be the coach, I probably would never have made the decision I made,” Lammert said.

Lammert went on to score 1,119 points in his UC career and was the No. 3 scorer in school history at the time of his graduation.

JUST A SHOOTAROUND, EH?

Lammert was a freshman during Wiethe’s final season. Lammert had just missed six games with an ankle injury but was scheduled to return to action January 15, 1952, at Ohio University. The Bearcats bused to Athens, Ohio, and arrived around 10 p.m. Wiethe took the players to the gym “just to get the rubber out” of their legs after the bus ride.

Lammert, whose ankle was still weak, asked whether he should get taped. “No,” Wiethe told him. “We’re just shooting around.”

By midnight, the Bearcats were going all out and full-court pressing. Lammert turned his ankle again and missed six more games.

“That’s just kind of the way he was,” Lammert said. “There we were, full-court pressing at midnight the night before a game when we were just supposed to be shooting around.”

CONSPIRACY THEORY

UC played at Western Kentucky on January 30, 1952, and lost 79-63. For some reason, the up-tempo Bearcats could not get out and run and had trouble keeping up with the Hilltoppers, who won their 72nd straight game at home. Another thing the players wouldn’t forget was a power outage at halftime.

The players were talking on the bus ride back to Cincinnati about the nets. They noticed that Western Kentucky was shooting into a basket with very tight strings, and the Bearcats would have to wait for the ball to come through every time WKU scored giving the Hilltoppers a chance to get back and set up their defense. The UC players also realized that the strings were very loose on their basket. The ball would go right through the net, allowing the Hilltoppers to take the ball out of bounds quickly and get a fastbreak going. This was strange because, of course, the teams changed baskets at halftime.

Larry Imburgia finally made the connection: When the power went out, the nets were switched.

“It was orchestrated, of course,” Jack Twyman said. “In retrospect, you realized that you’d been had.”

THANKS, COACH

In 1951-52, freshmen were eligible to compete on the varsity teams, and UC freshmen Twyman and Lammert played with the upperclassmen.

This was Wiethe’s last year as UC’s coach. But it was a season Twyman won’t forget.

On February 21, Cincinnati played St. John’s in New York. It was Twyman’s first trip to Madison Square Garden.

St. John’s was winning 38-30 at halftime. Twyman walked into the locker room and started to take a seat. Wiethe was already ranting and raving. “This is how you dive for a loose ball,” he shouted. And he dove straight at Twyman, knocking him right through a tear-away door and into the lobby.

“People are getting popcorn, and there I am laying flat on my back,” Twyman said. “And Weithe’s saying, ‘Now that’s how you go after a loose ball.’

“He was very intense. I feel very fortunate to have played for him. He certainly taught you to be competitive and to never give up. I learned a lot from John. I also learned a lot from George (Smith, UC’s head coach from 1952-60). He was like my father away from home.”

IMPRESSIVE

Imburgia, who averaged 24.2 points a game in 1950-51, had contracted polio as a child. However, he had some teammates who didn’t even know it.

“His left arm was almost useless, but he could flat-out play the game with that right hand,” Holstein said. “He had a great big hand. He could handle the ball and shoot it and jump real well.

“He put the left hand up to guide the ball but his right hand did almost everything. He never said anything (about the polio). You didn’t even think about it when we were playing with him. We just went out and played. We’d look at him and think: How the hell can he play? But he did a great job.”

INTENSE OFF THE COURT, TOO

Wiethe was big on conditioning. The Bearcats ran few drills under him; they mostly scrimmaged for hours.

The coach liked to stay in shape, too. He was roughly six foot two, 230 pounds. Big but agile.

To lose weight in the off season, he’d put on a rubber suit and play golf at Avon Field on Reading Road in Cincinnati. Wiethe would carry a 1-iron, a wedge and a putter and run the course to try to sweat off some pounds. He’d try to play 18 holes in one hour.

One night, he hit off the first tee and his ball landed right in the fairway behind a man who was playing ahead of Wiethe. But he didn’t care. Wiethe’s attitude was: Get out of my way.

The man playing ahead of him knocked his shot up on the green. Wiethe hit his ball onto the green close to the man, who then knocked Wiethe’s ball back at him. Wiethe grabbed his ball and approached the man, asking why he hit the ball his way. The man explained that he was upset Wiethe was hitting his shots so close to him.

Wiethe picked up the man’s bag of clubs and threw it off the base of the green. The guy came after Wiethe, who then picked up the man and threw him down toward his bag.

The man sued Wiethe for $10,000.

The next summer, Dallmer saw Wiethe and asked, “Whatever happened to that lawsuit?”

“Awww,” Wiethe said, “I gave the fellow a C-note and that was the end of that.”

“That’s just the kind of character he was,” Dallmer said of Wiethe.

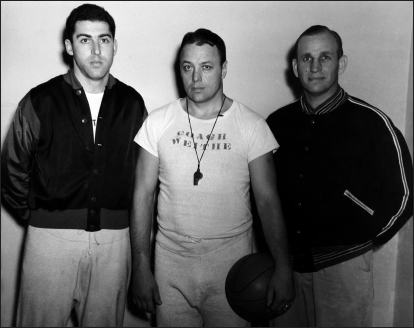

Dick Dallmer was a four-year starter at forward. During his career, the Bearcats went a combined 77-27. He was a team captain as a junior and senior. (Photo by University of Cincinnati/Sports Information)

ZONING OUT

And so the story goes it was 1948 or ’49, and the Bearcats were playing some of their games at Music Hall downtown. Wiethe was driving a carload of players to a game one evening. As he was driving, he was deep in thought about that night’s matchup and discussing strategies with the players in the car.

He stopped at a red light on Central Parkway, and he continued talking to the players as the light turned green, then red again. The driver in the car behind Wiethe started honking his horn.

Wiethe slowly got out of his car, walked back to the other car, opened the door, grabbed the man’s keys, and threw them. Then he walked back to his car, got in, and continued driving to the game.

MAKINGS OF SUCCESS

For all the antics, Wiethe was driven to get UC among the upper echelon of college basketball programs. He would play anyone anywhere and was the first to coach a Cincinnati team at Madison Square Garden in New York City. Under Wiethe, the Bearcats would also schedule games at Chicago Stadium and the Orange Bowl in Miami.

Wiethe, a lawyer who would eventually become head of the Hamilton County Democratic Party in Cincinnati, coached the first UC team to win 20 games in a season and the first to score 100 points. He left after UC finished 11-16 in 1951-52—his only losing season.

“We were the beginning of things,” Dallmer said. “We really got the program started.”