9

TONY YATES ERA (1983-1989)

ONCE A BEARCAT

Tony Yates was a Bearcat during three consecutive decades. He played in the 1960s. He was an assistant coach for Tay Baker, then Gale Catlett, in the ’70s. And he returned to his alma mater as head coach in 1983.

Yates had been an assistant coach at the University of Illinois for nine years—one under Gene Bartow and eight under Lou Henson.

In the back of his mind, he always hoped to one day coach the Bearcats. He said he interviewed for the job in 1972 when Baker resigned, but Athletic Director George Smith went with Catlett. Yates tried again when Catlett left in 1978, but Athletic Director Bill Jenike chose Ed Badger.

Toward the end of the 1982-83 season, with growing disenchantment with Badger, some UC alums contacted Yates to see if he was still interested in the job at UC.

Tony Yates’s tenure as head coach of Cincinnati did not bring the championship success of his playing days. Nevertheless, Yates brought many memorable moments to Bearcats fans, including the infamous slow-down game against Kentucky in 1983, the Bearcats’ first postseason appearance (NIT, 1985) in more than eight years, the snapping of UC’s 17-game losing streak to Louisville, and the recruitment of three 1,000-point scorers: Roger McClendon, Louis Banks, and Levertis Robinson. (Photo by University of Cincinnati/Sports Information)

There was no question about it.

Badger was out of work soon after the season ended. UC Athletic Director Mike McGee flew to Champaign, Illinois, to interview Yates at his home.

The other primary candidates were Lou Campanelli from James Madison and Ron Greene from Murray State. It came down to Yates and Greene after Campanelli withdrew from consideration.

Yates came to campus for a formal interview with the selection committee, which included Oscar Robertson.

On April 1, McGee called Yates at his home in Champaign and offered him the job.

“Now Mike, this isn’t an April Fool’s joke is it?” Yates asked.

“It was a very happy moment,” Yates said. “I was going home.”

When he was announced as head coach at the Alumni Center, more than 200 friends, former teammates, UC officials and supporters gave him a standing ovation. Yates had to wipe away tears.

Robertson told The Cincinnati Enquirer: “Am I happy? You bet. He knows the game. He knows how to recruit. He’s just what we need.”

BOOT CAMP

It did not necessarily please all the UC players that Yates brought with him a military background of regimen and discipline. The transition from the mostly laid-back Badger to Yates was eye-opening. Some players were certain Yates, a veteran of the U.S. Air Force, was trying to run everyone out of the program.

“It was a miniature boot camp,” Yates said. “We wanted the kids who really wanted to be there and who would conform to what we wanted.

“We weeded out the guys who didn’t really want to work. They began to leave one by one. A few we asked to leave. The guys who hung in there are the guys who really wanted to be there. Attitudes changed.”

Yates set strict in-season and off-season curfews. (“My junior year, you had to be in your room at 10; I can remember me and Joe Niemann sitting across from each other in the doorways talking because we weren’t allowed out of our rooms,” Doug Kecman said.) Yates required players to sign in at the basketball office by 7:30 a.m. each school day—if not they would have to run five miles at 5 a.m. the next day.

And he was relentless in practice. “We were in a military regime when he came in,” Kecman said. “We practiced for four hours every day.”

Sometimes longer.

“He had a lot of rules,” Derrick McMillan said. “A lot of rules.”

ICY START

This was Myron Hughes’s introduction to Yates.

Hughes had just finished his sophomore season at UC and was rehabilitating an injured knee. Yates called a 3 p.m. meeting, but Hughes had not finished icing his knee. He walked into the meeting a few minutes late and Yates jumped all over him. The two had never met.

“If anybody was always on time, it was me,” Hughes said. “My teammates knew I was always on time for everything. At that point, I told myself I was transferring. I didn’t want to take the opportunity to get to know him.”

Hughes contacted Tennessee and Virginia Tech and was getting ready to leave UC. But he decided that wasn’t what he wanted, that he had met so many great people at the university. So he decided to give Yates a chance.

After sitting out the 1983-84 season following knee surgery, Hughes played two seasons for Yates and grew to look at him as a father figure and confidant.

More than 17 years after his UC career ended, Hughes remained close with Yates, phoning him almost monthly.

“If I need advice, he’s one of the first people I call,” Hughes said.

PRACTICE ’TIL YOU DROP

Yates allowed his players to go home for Christmas in 1983, but they were all to return and get right back to work after the holiday. Back in Cincinnati, it was a cold, cold winter. And when the players returned to town, they found there were no lights and no heat in Dabney Hall, where they lived. There was also no heat in the Armory Fieldhouse, site of the first practice after the break. The players could see steam coming out of their mouths when they breathed.

When it was time for practice to start at 7 p.m., only four players were on hand: Kecman, Niemann, Mike McNally and Marty Campbell. Yates had them play two-on-two full court while they waited for the other players to trickle in. “Practice” continued until after 10 p.m. Derrick McMillan still was not there; he was involved in a car accident in Chicago heading to the airport. Neither was Mark Dorris, who had gotten married during the break. Eventually Yates told the players to head back to the dorm and he’d see them at 7 a.m. the next day.

Yates was obviously not in a good mood. After a four-hour practice in Laurence Hall (which did have heat), he had the Bearcats line up for sprints. Lots of them. The players were dropping out one at a time, vomiting on the sideline, unable to continue.

There were six players still running when Luther Tiggs passed out in the middle of the court from dehydration.

“Coach Yates really believed in conditioning,” Tiggs said. “It was one of those typical days. As we started our conditioning, one sprint led to another. And that just wasn’t enough. He never got satisfied.

“I practiced extremely hard. I didn’t believe in saving anything. It just seemed like it was never going to stop. The teammates were encouraging each other. The coaches were really pushing us. I was out of gas. I remember getting extremely light-headed. I looked at the coaches and they indicated we needed to get back on the line. I was totally exhausted. The only thing I remember after that was I was in the student medical center and I had an IV in my arm and a couple of the guys were giving me a hard time because they thought I was bailing out.”

After Tiggs went down, Kecman looked at Niemann and said, “We’ve got to be done.”

As soon as Tiggs was taken out of the building, Yates said, “Get back on the line.”

They ran some more, then had to come back for a 4 p.m. practice.

ONE ON ONE

That wasn’t the last time Tiggs got a hard time from his teammates. Or Yates.

He missed two games during the 1983-84 season when he suffered a broken finger playing against . . . a girl!

OK, to be fair, Tiggs wasn’t playing just any female when he got hurt. He was in the Armory Fieldhouse playing one on one against Cheryl Cook, the greatest player in UC women’s basketball history whose jersey number is retired and hangs in Shoemaker Center.

“She was the best women’s player I ever saw,” Tiggs said. “She was extremely competitive. She always wanted to play with the guys. They called her a few names, but nobody gave her an out. That’s what she wanted.

“One day, she wanted to play one on one at a side basket. She had the ball and she made a move toward the baseline and my hand went across the body because I wanted to strip her of the ball. I pulled it back. When I looked up, my index finger was completely severed. I ran to the trainer, and my finger was just hanging there. They had to stitch it up. The guys were really on me about that. Coach didn’t want to believe it.”

As for Cook, Tiggs said she felt badly.

“She was real sweet about it,” he said. “She didn’t want to make (the men’s team) mad.”

“It wasn’t intentional,” Cook said. “Now that you brought it up, I still feel bad about it.”

COOKIE MONSTER

Since Tiggs brought up the subject, it’s appropriate to take a timeout from the men’s program to talk about Cheryl Cook, AKA the Cookie Monster.

In Shoemaker Center hangs the retired jersey numbers of Oscar Robertson, Jack Twyman, Kenyon Martin and . . . Cook, No. 24.

A native of Indianapolis, Cook was second in the country in scoring (27.5 ppg) and second-team All-America as a senior in 1984-85, and she remains the women’s all-time leading scorer at Cincinnati with 2,367 career points. (That was the seventh best total in NCAA history at the time.)

The five-foot-nine guard was a two-time Metro Conference Player of the Year. She played on the 1983 gold-medal-winning U.S. team in the Pan American Games and on the silver-medal-winning U.S. team in the 1985 World University Games.

Cook was Indiana’s Miss Basketball in 1981 as a senior at Indianapolis Washington High School. She said she had 375 scholarship offers from colleges and narrowed her choices to USC, UCLA, Hawaii and Cincinnati.

She wanted to leave the state of Indiana but stay close enough to home so her parents could see her play.

“Plus the (UC) coaching staff was just awesome,” Cook said. “They were real people-oriented. It was a close-knit family within the team, and that’s what I was looking for.

“I was going there to try to make some noise and get us national recognition.”

She would play two years for coach Ceal Barry, then two for coach Sandy Smith.

During her career, the Bearcats went a combined 70-45. Cook’s only regret was that UC never went to the NCAA Tournament when she was there.

“But we came a long way as a program,” she said. “It opened a lot of doors for other women to come in and try to take it to the next level.”

Two memories stand out for Cook.

One was when the Bearcats went to Tennessee in the third game of her senior season and upset the 12th-ranked Volunteers. Cook scored 34 points.

The other is how she sometimes practiced with the UC men’s team and competed against guys in pick-up games on campus.

“I grew up with six brothers, so I was accustomed to being the only girl, being knocked down,” Cook said. “I played AAU with the boys when I was younger. I wanted to show them at UC that I was capable of playing with them. Some of the guys at the beginning underestimated me—until I got out there and played.

“I grew up with that drive to be better than the next person. I lived in the gym. As far as a personal life and hanging out with friends, I didn’t have all that because I was dedicated to the sport.”

Cook was one of the top college players in the nation and went on to play four years in Spain and two years in Italy after leaving Cincinnati.

“I feel privileged,” she said. “I wish there were more (women’s numbers retired), but I’m thankful for every opportunity UC gave me.”

SO MUCH FOR THAT IDEA

Seven games into his junior season, Doug Kecman had a great shooting night, scoring 10 points in a 55-50 loss to Miami University at Riverfront Coliseum. He scored the Bearcats’ last eight points and hit five jumpers from the corner that would have all been three-pointers if the three-point arc existed then, which it didn’t.

The 1-6 Bearcats’ next game was against No. 2-ranked Kentucky at Riverfront. At practice the day before meeting the Wildcats, Yates told Kecman that he was going to be in the starting lineup and that with Kentucky playing a 1-3-1 defense, he could get open for that shot in the corner all night. During practice, Kecman said, “I was bangin’ them home. I was hitting every corner shot you can imagine.”

I’m gonna have a career game against Kentucky, he thought.

Kecman was fired up. He got on the phone that night and called his friends back home in the Pittsburgh area.

“We’re playing on ESPN tomorrow night and I’m going to get 20 (points) against Kentucky,” he told them. “I’ve got the green light to shoot everything from the corner.”

Well, most UC fans know how this story turns out. Yates told the Bearcat players just before they went out for the tipoff that they were going to hold the ball. All game.

That blows the 20 I’m going to get, Kecman thought,but I’m still starting on national TV.

“I played 39 minutes that night and didn’t break a sweat,” he said. “I did grab a rebound over Sam Bowie—he kind of slipped and fell.”

He took one shot all night—and missed. Kecman was scoreless.

The final: Kentucky 24, UC 11.

CINDERELLA STORY

Tony Wilson came to UC from Toledo on a track scholarship (he was one of Ohio’s top high school hurdlers), but as a freshman he also was interested in playing basketball. He tried to walk on to UC’s team but did not make it.

Derrick McMillan, at Cincinnati on a basketball scholarship, was also on the track team as a freshman and got to know Wilson. The night before walk-on tryouts in the fall of 1982, McMillan said he saw Wilson at a party. Wilson said he wasn’t going to try out again. McMillan had seen Wilson play pick-up games, and he liked guys who wanted to play defense and played with a lot of heart. Wilson was also pretty quick, like McMillan.

“It’s like 2 a.m.,” McMillan said. “I told him, ‘You’ve got to come try out. You’re going to practice at 8 o’clock in the morning. I’ll be there personally.’ I asked (the coaches) to give him a fair shot as a walk-on. The rest is history.”

Wilson made the team, impressed coaches with his hustle and determination and was a starter by January of his sophomore year. He is probably best remembered for his 49-foot shot that upset 17th-ranked Alabama-Birmingham at Riverfront Coliseum (69-67) on December 12, 1984.

After UAB tied the score with five seconds left, Wilson got the ball, dribbled once and looked at the clock. “It read :02, and I let it go,” he said afterward. “I knew I had the distance.”

“I remember the circumstances real well because I wanted the ball so bad,” McMillan said. “It was something I practiced every day. Tony reaches out and gets the ball and sends it up, Cinderella style. It was the shot heard ’round the world.”

JEKYLL AND HYDE

There were more than 16,000 fans in attendance, but few saw it happen. All of a sudden, Xavier University’s Eddie Johnson was on the ground.

It was the January 30, 1985 Crosstown Shootout at Riverfront Coliseum. It was the usual heated battle between the Bearcats and Musketeers.

Myron Hughes and Johnson were battling under the basket.

“We started running down the court and he shot me two elbows,” Hughes said. “I just reacted. I turned around and slugged him and knocked him down. I hit him pretty good. He wasn’t knocked out, but he was stunned. I didn’t think about being kicked out of the game or anything.

“A lot of people say they saw it even though they didn’t. The three officials working the game missed it. No one else on the court saw anything. I would venture to say no more than 15 people actually saw it. The referee came up to me and said, ‘I don’t know what happened but I know something happened. You guys need to clean it up.’”

No foul was called. Hughes was not ejected. Xavier went on to win 55-52. There was no mention of the incident the next day in the morning newspaper.

Hughes is often reminded of the incident before Crosstown Shootouts. But he has no regrets.

“I’ve been hit in the mouth and upside the head and punched in the side,” he said. “When you’re playing underneath the basket, there’s no telling what will happen.

“There were no hard feelings. He knew what he had done. We’ve even gone out and had drinks. It is weird. I didn’t think too much about it. I would never have thought I’d be talking about it 19 years later and they’d still be showing it on television.”

The funny thing is, those who know Hughes off the court would think it was so out of character. But those who played with him, know a different side of Myron Hughes the basketball player.

“He was our protector,” Roger McClendon said. “He was the father figure, the big brother. Out of character? Not on the floor. You know how some people could get in the ring, like Muhammad Ali, and punish a guy, but then off the floor he’s kissing babies? Myron had that split personality. You knew when you were on the court, if you went through the lane, you’d better be prepared no matter who you were.”

ANOTHER “BIG O” ASSIST

Oscar Robertson says University of Cincinnati players have had an “open invitation” to work with him individually for decades. But few over the years have asked for guidance from one of the greatest basketball players of all time.

The summer of 1984, before his senior year, Derrick McMillan was talking to Yates about Robertson.

“Give him a call,” Yates said.

“No,” McMillan said. “You don’t just call Oscar.”

“Call him, Derrick,” Yates said.

Yates gave Robertson’s phone number to McMillan, who soon called.

“He had a shooting problem,” Robertson said.

The two met at the Armory Fieldhouse, steaming in the summer heat. McMillan came from a factory job. Robertson came from his office. They got together every day between 4:30 and 5 p.m. for roughly an hour. Robertson showed McMillan a proper shooting technique. He taught him about studying film and watching other players.

“It’s amazing, the things he taught me still work today,” McMillan said 19 years later. “The things that he taught me in that period of time are things that I share right now with kids.

“There’s something about him that really led me toward the things I wanted to do with leadership. I watched the way he carried himself on and off the floor and how he went about approaching things. Even when I’m around him now holding conversations about the way people do business, he just really makes you feel good and makes you look at things that you should be correcting.”

It should be noted that as a senior, McMillan averaged a career-high 11.7 points—more than twice his average from his junior year—and was selected second-team all-Metro Conference.

“I tell all the players before the season, if you want to work on some things, here is my number,” Robertson said. “Whatever they want to do is fine with me. If they want to work every day, I don’t mind. For some reason, most of them never took advantage.”

McMillan couldn’t be happier that he did.

CLOSE, BUT NO

Going into the final game of his injury-plagued career, Hughes still had a chance to reach the 1,000-point mark. He needed 17 points against Louisville in the 1986 Metro Conference tournament.

“I knew what I needed,” Hughes said. “But at that time, I was more worried about how we could win the tournament and get to the NCAA. That was one of my goals, and we never did do it.”

Hughes had scored 12 points, and with 12:53 to go in the game he was called for a foul. He thought he only had four, but then he heard the buzzer and saw a person at the scorer’s table hold up five fingers. He had fouled out and finished with 995 career points.

“Unfortunately, I did not know how many fouls I had,” he said. “It would’ve been a milestone, but I didn’t think about it that much. I knew I missed a lot of games. If I would’ve played in another couple games, I would’ve made it to that level with no problem. I was mostly concerned with winning.”

Hughes estimates missing roughly 25 games during his career. He had four surgeries on his left knee (including one reconstruction), bursitis in his right knee, a broken finger and nose, a tooth knocked out, 14 stitches above his eye, and torn muscles in his thigh.

Hughes served as executive director of the University of Cincinnati Alumni Association from 2008-14 and is currently UC’s senior associate vice president of development for diversity & inclusion.

STUDENT ATHLETE

Roger McClendon was a McDonald’s All-American coming out of Centennial High School in Champaign, Illinois, but in choosing a college, he had more on his mind than just basketball.

His father was a professor of African-American History at the University of Illinois. His parents stressed the importance of education. McClendon was interested in majoring in engineering.

When it came time to meet in person with Division I head coaches, the McClendon family prepared just as hard as the coaches. Roger and his parents came up with a list of 25 questions that every coach wanting to sign Roger would have to answer. Among the questions: If Roger got injured his first season and couldn’t play anymore, would the school honor his scholarship for as long as it took to get a degree? Or, what if Roger wanted to grow a mustache or beard or wear a goatee? Was facial hair allowed?

It was that one that tripped up Villanova coach Rollie Massimino, who said the rules of his program prohibited facial hair. McClendon’s father objected.

“I guess the point was, as you’re growing up as a young adult, there are certain decisions you should be able to make, and whether you have a mustache or not doesn’t impact the way you play basketball and doesn’t define your personality,” McClendon said. “You do need some freedom of choice. You’re growing as an individual.”

So, they all answered the questions. Denny Crum from Louisville. Bobby Cremins from Georgia Tech. Lou Henson from Illinois. C.M. Newton from Vanderbilt. Even Bob Knight, whose Indiana program was not in McClendon’s final five.

Of course, there was also Yates, who was in his first year as head coach at the University of Cincinnati. Yates had known McClendon’s family for years because he was an assistant at Illinois and had been hoping to lure McClendon to the Fighting Illini.

The more McClendon learned about UC, the more it climbed on his list. He had no idea how successful the program had been in the 1960s. He didn’t realize the university boasted a top-flight engineering program and that it had a co-op program that would allow him to gain practical job experience while in school.

“Really what I was looking for was a combination of an academic school that focused on engineering in addition to a high-caliber basketball program,” McClendon said.

“The challenge for me would be to carry both of those torches at the same time.”

THE PACT

McClendon attended the University of Cincinnati’s basketball camp in 1984. Among the other players at camp: Elnardo Givens from Lexington, Kentucky, Levertis Robinson from Chicago and Ricky Calloway from Cincinnati’s Withrow High School. Unknown to Yates at the time, the four made a pact to sign letters of intent to attend UC.

All but Calloway—who went to Indiana University—followed through.

“We did talk about it, that it would be a great place to build the program together,” McClendon said.

By the way, another player at that camp was Ben Wilson, the top-rated high school player in the country from Chicago who was tragically shot and killed in November 1984.

“Ben Wilson was very interested in coming to Cincinnati,” McClendon said.

BALANCING ACT

McClendon was UC’s leading scorer for his first three seasons all while holding a double major in chemical and electrical engineering.

How did he pull that off?

“I probably missed out on parties that a lot of people had a chance to make,” he said. “I knew where all the action and all the fun was at. You had to make a choice. I didn’t regret it. What I had to do was find a balance.”

He remembers when a band called Red, White and Blue was performing at Bogart’s on Short Vine, and there were rumors Prince was going to show up. A lot of players and people McClendon knew went to the show—and Prince did show up.

When his friends returned to Dabney Hall, one had a tambourine from the band and another had a drumstick. They couldn’t stop talking about what a great concert they had seen.

“And I’m under a light reading a physics book getting ready for a test,” McClendon said.

One of his favorite extracurricular activities was when he was co-campaign manager for Stan Carroll, a candidate for student body president.

McClendon spoke on Carroll’s behalf around campus and helped have flyers printed up. “I enjoyed that,” McClendon said. “There were things that I wanted to do, and I had to make an extra effort to do them and not be just one-dimensional. I did try to find that balance. But it’s always a struggle to try to reach your peak in both academics and athletics.”

OLD SCHOOL

McClendon became close friends with teammate Romell Shorter, an exciting player from Chicago Martin Luther King High School. McClendon remembers one game during the 1985-86 season when Shorter, a five-foot-five guard, dribbled four times between his legs, once behind his back, then went around an opposing defender for a layup.

The next day, Yates showed the play on video three or four times in a row and asked the players to analyze whether all those moves were necessary for Shorter to get in position to make the shot.

“Coach Yates was an old-school style of coach,” McClendon said. “To him, that was a fancy move. We all laughed. With Romell, that’s his game. Without him using that ability, he becomes like everybody else.”

WHAT A SHOW

When McClendon was a sophomore, the Bearcats played at Louisville when the Cardinals were ranked 18th in the country (January 20, 1986). Yates calls it “the most fantastic show” McClendon ever put on.

Louisville was ahead 56-43 with 13:20 remaining. From that point on, the UC offensive plays were all called for McClendon. The Bearcats went on a 14-4 run with McClendon scoring 10 of their points.

“We tried eight or nine different players on him and it didn’t make a difference,” Cardinals coach Denny Crum said afterward.

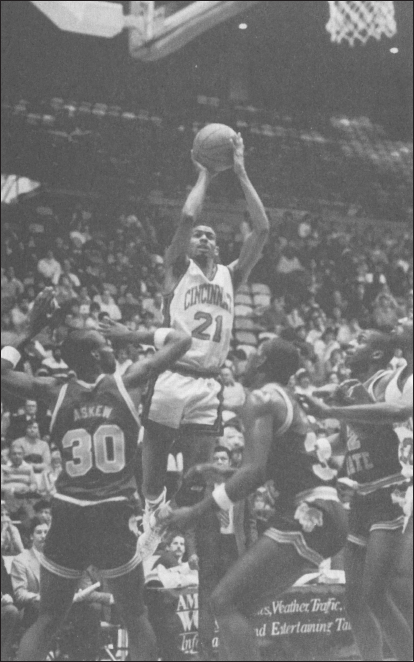

Always the outstanding student, Roger McClendon (21) passed up a professional basketball career and obtained his UC degree in engineering. Today, he is chief sustainability officer for YUM Brands, Inc., in, of all places, Louisville, against whom he had some of his most spectacular games. (Photo by University of Cincinnati/Sports Information)

“We were all over him and he filled it up anyway,” Louisville player Billy Thompson told the media.

McClendon scored 24 of his 35 points in the second half and led Cincinnati to an 84-82 upset victory.

“I just know it was one of those rhythmic type of games where you didn’t hear anybody in the stands and things felt like they were in slow motion,” McClendon said. “It was easy.”

He was 10 of 14 shooting from the field in the second half.

“He hit from all over the place,” Yates said. “Louisville played a switching defense. He just beat them all. He penetrated, he pulled up, he shot from the corner, he shot from the wing, and he shot from the top of the key. Everywhere. That was really a special game.”

Yates kept a tape of that game and said he plays it every once in a while.

“There was something special about playing Louisville,” McClendon said. “I had the opportunity to go there. I knew Milt Wagner. They just had that type of team that would peak at the right time. But there was always something about playing Louisville that brought the level of the game up for me.”

UC beat them twice that season. Louisville went on to win the national championship.

SHOULD I STAY OR SHOULD I GO?

UC finished 12-16 in 1985-86, McClendon’s sophomore season. Though he had led the Bearcats in scoring two years, McClendon’s parents had concerns about Yates’s coaching style and philosophy. They attended a lot of games and were not sure their son was reaching his potential as a player.

There were discussions about possibly transferring, though McClendon never contacted another school.

“My dad thought I was probably not reaching my full potential,” McClendon said. “I was frustrated but not unhappy. I was frustrated with not winning. The tough challenge with not winning is that nobody’s happy. You don’t have to be the star of the team. I would’ve much rather been on those 1960s teams and won a national championship than be the star of the team.”

What kept McClendon at Cincinnati was probably this: His priority was not preparing for an NBA career. If it were, he knew there were better places for him to play.

“I was there really to get an education,” he said. “That was my focus.”

NOT SO EASY GOING

As basketball stars go, McClendon was a pretty levelheaded, calm, easygoing guy. But that demeanor went by the way-side February 16, 1987 when the leading scorer in the Metro Conference (19.7 ppg) learned that he was being benched for the start of a game against Memphis State.

Yates decided to sit McClendon, Joe Stiffend and Calvin Pfiffer and start Marty Dow, Don Ruehl and Romell Shorter.

“It’s like being helpless being on the bench,” McClendon said. “Not being able to do what you do was a tough thing. For me, it was all about the competition. I’m competitive to this day.

“He probably got the reaction he was looking for. Sometimes as a young player, you can’t see what a coach can see with more experience. Coaches have to try different things to motivate players, to motivate the team.”

McClendon, Stiffend and Pfiffer entered less than five minutes into the game. The Bearcats went on to win 76-73 at Riverfront Coliseum.

“I’m still angry (17 years later),” McClendon said laughing.

“I CARRIED A LOT OF WEIGHT”

McClendon, who left UC as the school’s No. 2 all-time scorer behind Oscar Robertson, is the only Bearcat among the school’s 1,000-point scorers to suffer through three losing seasons in his college career.

After UC went 17-14 his freshman year, McClendon’s final three teams went 12-16, 12-16 and 11-17.

“I carried a lot of weight on my shoulders,” he said. “I felt more responsible for having a losing season. Every game we would lose, I didn’t feel like getting up and going to class and showing my face in public. I looked at myself like I should’ve been able to do more. That was a struggle for me, feeling like I let the team down. I kept that inside, which is not a good thing.

“It’s hard to not be in a winning environment. It was very frustrating. Not with the players and not necessarily with the coach, but just going through that experience. I think it made me stronger. I did feel I had the potential and capability to go on to the next level, but I didn’t.”

McClendon was not picked in the three-round NBA draft. He played for the Miami Tropics of the United States Basketball League in the summer of 1988 and was invited to NBA camps by the Portland Trail Blazers and Chicago Bulls. He pulled a groin muscle while playing for the Tropics and never did attend the camps. He said he also turned down guaranteed money to play in Barcelona.

Instead, McClendon returned to the university for the 1988-89 school year to complete the requirements for his undergraduate degree. Again, he had a chance to begin a basketball career overseas. McClendon decided to accept a full-time engineering job.

He never played organized basketball again.

“I don’t know if I really wanted it that bad,” he said. “I finally let it go after two years of being in engineering.”

XAVIER’S LOSS, UC’S GAIN

Keith Starks grew up in Addyston on the west side of Cincinnati and attended Taylor High School. He was a big Xavier University fan and rooted for the Musketeers each year during the Crosstown Shootout against Cincinnati.

By the end of his sophomore year at Taylor, Xavier was recruiting Starks hard. XU assistant coach Mike Sussli sent letters every day. No school came after Starks more aggressively. “If I would’ve signed my junior year, I would’ve gone to X,” Starks said.

Gary Vaughn, his high school coach, encouraged Starks to take his time, make some visits to other colleges. Eventually, Starks narrowed his choices to Indiana, Syracuse, UCLA, Xavier, and UC—with UC “a distant, distant fourth or fifth.”

Starks visited UCLA and loved it. He was all but ready to commit to the Bruins. Then his grandfather became ill. Starks grew up with his grandparents, and he didn’t want to leave Cincinnati at that time.

Two factors ended his desire to go to Xavier. One, coach Bob Staak left and was replaced by Pete Gillen, and Gillen’s staff went after another local product, Withrow’s Tyrone Hill, and cooled on Starks. Even before that, Starks had decided to play football his senior year at Taylor. Starks said Sussli discouraged it and questioned the decision. UC assistant coach Jim Dudley thought it was a great idea and told Starks it would help his strength and conditioning. Starks—playing organized football for the first time in his life—started at split end and safety in high school.

In the spring of his senior year at Taylor, Starks signed a letter of intent to attend UC, a school that hadn’t even been on his so-called radar screen.

“If my grandfather wouldn’t have gotten sick, I would’ve gone to UCLA,” Starks said.

LEARNING CURVE

Starks arrived at UC in 1987. He was a big-time scorer at Taylor, and the first day of practice with the Bearcats, he shot the ball almost every time he touched it. Yates stopped practice and tossed Starks the ball. “Here Keith, shoot it,” Yates said. He did. Yates gave it back. “Shoot it again.” Everyone was looking around, wondering what was going on.

Finally, Yates said, “Have you gotten it out of your system yet? Because you’re not going to shoot the basketball. You’re just going to go out and play as hard as you can, play defense and rebound. We have plenty of shooters.”

The first four games, Starks hardly played. It was a tough transition.

WHAT A FIND

Sometimes, this is how recruiting works.

Yates and assistant coach Ken Turner were traveling through Montgomery, Alabama on the way to try to contact Leon Douglas, a star high school player from Meridian, Mississippi.

Turner was friends with an Alabama high school coach, and he suggested stopping off to see him to inquire about any talented players in the area.

Turns out there was a big kid, a raw talent, at Noxubee County High School in Macon, Mississippi. Yates and Turner dropped by to see him.

The player’s uncle was the band director, and the coach had just plucked the kid out of the marching band. He had grown seven inches over the summer and entered his sophomore year six foot six. But he had never played organized basketball.

“He runs the floor like a deer,” the coach said. The kid’s name was Cedric Glover.

Glover played the drums and trumpet. He had cousins who had received music scholarships to college, and that was the path he was following.

William Triplett was the school’s basketball coach, and he also happened to have Glover in his history class. Every day, he talked to Glover about trying out for the team. “I’m coming, I’m coming,” Glover would tell him. But he never did show up.

One day, Triplett walked Glover to the gym after class and had him watch practice. Glover expressed interest and said he’d start the next day. He didn’t. A few days later, the coach again walked Glover to the gym—and this time he had practice gear waiting for him.

“There was no getting out of it,” Glover said. “So I actually got dressed to be a part of a team I had no intention of being a part of. I didn’t have a clue about any of the rules. I didn’t understand basketball, but I could run a little faster and jump a little higher than other guys.”

The UC coaches followed his progress and recruited Glover hard. But so did powerhouses like Houston, Louisville, and Georgetown. All those schools suggested he redshirt as a freshman. Yates told him he’d have the chance to play right away at UC; plus, Glover had relatives in Cincinnati. He signed with the Bearcats.

Yates says Glover was “the worst basketball player in the United States” when he arrived at UC.

“He was big and strong, but he didn’t know how to play,” Yates said. “He had bad hands. He would travel all the time. He was a very sensitive kid. Not a lot of confidence.”

A knee injury forced Glover to sit out his junior season, which gave him time to mature and get stronger. Glover was first-team all-Metro Conference in 1988 and ’89.

“He came a long way,” Yates said. “He worked very hard and became an excellent player for us.”

“Sitting out really, really helped me develop my body physically, helped me get stronger, helped me learn more about basketball,” Glover said. “When I look back on it, coming into the university, I should have redshirted. All those other schools that were recruiting me were right. I needed to develop more.

“Everything I earned and gained was due to hard work. I put in a lot of time in the weight room and did what I needed to do to get better. I put on my hardhat every day and I came to work and that was pretty much it for me.”

THANKS TO BENCH, ROSE & CO.

Who would have known that the star basketball player from Camden, New Jersey, was such a big Cincinnati Reds fan?

Lou Banks’s father loved the “Big Red Machine” and talked about them all the time. He took his son to see the Reds when they were in Philadelphia to play the Phillies.

So when the University of Cincinnati came calling in 1986, Banks felt it was the place to be. He chose UC over Louisville, Temple, and Rutgers and was the fifth-leading scorer in school history when he left.

“When I came on my recruiting visit, I had a great time and already liked the Reds, so it seemed like it was a fit for me,” Banks said.

WHERE IS EVERYBODY?

The play was not designed specifically for him. But Vic Carstarphen, a six-foot-one freshman, found himself with the ball as the clock was running out. “I played high school ball with Lou Banks. He said, ‘Listen, if it comes to you, take the shot.’ That’s all I remember,” Carstarphen said.

So Carstarphen drove the lane and hit a running 12-foot jumper from just inside the foul line with 10 seconds remaining. That gave UC a one-point lead against Morehead State on December 2, 1988. He would help force a turnover and lay in another basket at the buzzer.

Four points in 10 seconds. The Bearcats won 67-64 at the Cincinnati Gardens.

So how did he get treated afterward? Well, by the time he finished postgame interviews and got dressed, he discovered the team had left the building.

“I really didn’t understand the whole leaving on the bus thing,” Carstarphen said. “We would have to catch vans back and forth (from campus). I guess everybody left. I remember thinking, ‘I hit the game-winning shot and now I’m stuck.’ I thought it was a joke actually. I thought it was a freshman joke.”

News Record reporter Rodney McKissic ended up driving Carstarphen back to campus.

“I remember Vic walking outside and looking around for the vans, but they were all gone,” McKissic said. “I said, ‘I think they left you, need a ride?’ It was so funny. The guy just won the game for the team and they left him at the arena.”

Carstarphen transferred to Temple after the season. He would return to Cincinnati and play at Shoemaker Center as a senior in December 1992. But that didn’t turn out to be a pleasant experience. A.D. Jackson fell on Carstarphen while the two went after a loose ball, and Carstarphen broke his left leg in two places.

“I came back in the NCAA Tournament at the end of that year,” Carstarphen said. “But I was not 100 percent.”

LOU’S GOT A BOARD

UC had just returned from a road trip to Tampa, where the Bearcats lost 82-65 to South Florida, whose six-foot-seven center Hakim Shahid finished with 14 points and 20 rebounds.

The Bearcats were in the locker room before practice December 14, 1988. Miami University was next on the schedule. And Banks and Glover got into an argument.

Glover, the six-foot-eight, 235-pound team captain and the biggest and strongest Bearcat, was telling the UC perimeter players that if they had played better defense, the Bearcats might have fared better against South Florida. USF guards Andre Crenshaw and Radenk Dobras combined for 39 points, 12 rebounds and nine assists.

“What are you talking about?” responded Banks, 6-6, 195 pounds, who had totaled just two points in the game. He pointed out that Glover’s man was unstoppable on the boards. South Florida had outrebounded UC, 61-40.

They began to fight. Glover grabbed Banks and dragged his head across the locker-room floor.

“I was the captain of the team,” said Glover, who played the South Florida game with the flu and finished with 12 points and five rebounds in 25 minutes. “With every team, there’s going to be a guy that for some reason doesn’t want to follow the program. He just happened to be that guy. I was the policeman. I was the disciplinarian. I dragged him around. I made him a part of the locker-room decorations. He got a good whipping that day.”

Banks was furious.

“He took my face and dragged me on the carpet,” Banks said. “I didn’t appreciate that. I didn’t think because he was bigger he should’ve been trying to bully me.”

Banks left the locker room and went outside. “I didn’t collect myself,” he said. The first thing he saw was a four-foot-long board with several nails sticking out of it at the Shoemaker Center construction site.

Banks came into the Armory Fieldhouse waving the board in the air and yelling. The players were warming up before practice. Banks headed straight for Glover.

“Lou’s got a board!” Yates reportedly yelled.

“Buddy, bring it on,” Glover shouted at Banks.

Assistant coach Ken Turner and Yates stopped Banks.

“I was just really hot that day,” Banks said. “Yeah, I would’ve hit him if they wouldn’t have grabbed me, because he manhandled me in that locker room. I probably would’ve hit a couple of those other guys for not helping me.”

Banks said he was mad at Glover for “about 10 days.” Fifteen years later, the two laugh about the incident.

“I’m not embarrassed about it, because it happened,” Banks said. “When I look at now, I’m thinking, yeah, that’s crazy, but at that time I was very angry because of the way that he did me. It is funny now. It didn’t last very long. I never hold a grudge against a guy.”

“It just kind of diffused,” Glover said. “It’s a big joke now. But at that time, we were in the heat of battle. It just exploded all at once. Once that episode happened, everybody kind of fell in line. And I kind of developed a reputation not only in the locker room, but throughout the football team and the entire athletic dorm.”

SO LONG, FAREWELL

Glover’s senior night was anything but memorable.

Sure, his parents were at the Cincinnati Gardens for his final home game—against South Carolina—and they were on the court before the game with their son, who received a nice ovation.

But Glover was hurt and couldn’t play. He had sprained his left ankle at Virginia Tech on February 18 and had not played in three games. Still, Yates wanted him to make an appearance, so he started and played about two minutes. He had no shots, no rebounds, no nothing. He finished 49 points shy of joining the 1,000-point club.

“I’m out there just barely limping around,” Glover said. “That’s how it ended. It was kind of a downer. But you know what? I developed so many relationships with people associated with the university, so many relationships with people you cherish off the court.”

HOW IT ENDED

The way the Tony Yates era came to an end somewhat surprised the coach and some of the players.

“We kind of heard rumors, but we didn’t pay attention to them,” Andre Tate said. “We were kind of shocked when it happened.”

UC finished 15-12 in 1988-89 and won four of its last five games, including a 77-71 upset of No. 14-ranked Louisville at Freedom Hall. When the season ended, Yates didn’t hear a word from first-year Athletic Director Rick Taylor. Yates had one year left on his contract.

Around 2 p.m., the day of the team’s postseason banquet, Taylor called Yates to his office. Even then, Yates said, he didn’t know what was coming. Taylor told him he was making a change. “I was caught by surprise,” Yates said. “You have a winning season, you don’t expect anything like that to happen.

“I told him, ‘This is a helluva time for you to do that. It’s not very fair to me, and it’s not very fair for the kids.’ We conducted the banquet as if nothing ever happened.”

After the banquet, held in the student union, Yates told his players in an emotional meeting. Taylor told the media in his office. Yates did not speak to reporters that night.

He never coached again.

“I was very philosophical about it,” he said. “It’s just a fact of life that there are certain times you move on, no matter what you’re doing. It was time to move on. I had my life to live. The worst thing you can do in life is hang on and brood about those kinds of things.

“I didn’t want to coach anymore. I had my fling. I did what I wanted to do. I wanted to coach at the University of Cincinnati. I’m very pleased, very blessed, and very happy about what we had done. There were a lot of very special moments with a lot of special people. There are a lot of great, great memories.”