If we don’t understand the problem, it’s unlikely we’ll be able to fix it. So let’s begin by asking, with regard to the climate crisis, what is the problem we need to fix?

Often in public policy, the problem we need to fix isn’t immediately obvious. Sometimes we see symptoms without seeing the underlying problem. Other times we see part of the problem but not the whole.

On the surface, global warming appears to be an environmental problem. But deeper down, it’s a result of two economic and political failures.

The first of these is a market failure. Humans are dumping ever-rising quantities of carbon dioxide into the atmosphere because there are no limits or prices for doing so. There are, however, huge costs—costs that are shifted to future generations. When people don’t pay the full cost of what they’re doing, but instead transfer costs to others, economists call this a “market failure.” Nicholas Stern, former chief economist at the World Bank, has said that climate change is “the biggest market failure the world has ever seen.”

The second cause of global warming is misplaced government priorities. Because polluting corporations are powerful and future generations don’t vote, our government not only allows carbon emissions to grow, but subsidizes them in numerous ways. It gives tax breaks to oil companies, spends billions on highways, and devotes a large part of its military budget to defending overseas oil supplies.

Climate change is the biggest market failure the world has ever seen.

The root causes of climate change are two system failures: a zero price for dumping carbon into the atmosphere, and too many government subsidies for polluting activities and companies. Unless we fix both system failures, we’ll never stop climate change. Illustration by Dennis Pacheco.

It’s important to recognize that these twin failures permeate our entire economy. They’re not problems of the electricity sector, the automobile sector, or the building sector; they’re problems of all sectors and must be treated at that level. They distort the behavior of all individuals and businesses. No matter how “responsible” any of us may be, our separate actions can’t overcome what these twin failures make most of us do most of the time.

What’s required are fixes for both system failures. We need to limit and pay for atmospheric pollution, and we need to shift subsidies from dirty fuels to clean ones. If we don’t do both of those things, we won’t stop climate change.

What makes good climate policy?

Policies are attempts by government to solve problems. They can be evaluated on three grounds:

1) How effectively do they solve the problem?

2) Whose interests do they serve?

3) What principles do they advance?

Some policies are little more than hot air. They’re efforts by politicians to look good without offending their backers.

Many policies tackle only part of a problem. They may achieve small gains, but they don’t address the core problem, which continues to get worse.

Some policies are giveaways to private interests. Typically, they’re cloaked in public-interest language, but their effect is to enrich a few corporations. Lobbyists work hard to get policies like these.

Many policies don’t address the core problem, which continues to get worse.

A few policies genuinely solve big problems, serve the interests of ordinary people, and advance important principles such as fairness and transparency. These are the policies citizens should actively support. Social Security, for example, solves the problem of old-age poverty in a way that benefits all. That same standard should apply to climate policy.

Any solution to climate change must begin with clear goals. Then, measures must be taken to achieve those goals. It’s quite possible that the measures taken will be inadequate, but without clear goals we won’t know how we’re doing.

Climate goals can be expressed numerically and in terms of system design. The most important numeric goal is to reduce carbon emissions to a level at which the Earth’s climate will stabilize.

The most widely accepted scientific study—made by the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change—says we must reduce carbon emissions 80 percent by 2050. That works out, on average, to 2 percent of current emissions per year.

It’s important to understand what these numbers mean. On the one hand, cutting emissions 2 percent in a year is manageable. It avoids shocking the economy and allows legacy industries to phase out past investments gradually.

On the other hand, cutting emissions 80 percent by mid-century means we have to build an entirely new energy infrastructure. That’s no small challenge, but it’s one that America can meet. Look what we built in 40 years after World War II. We could do that again, this time with protection of the planet in mind. And in the process, our economy would boom.

In terms of system design, our goal is to build a simple, fair, and market-based system for limiting use of the atmosphere. That too can be done.

Government has four tools for achieving climate goals: taxes, caps, regulations, and investments. It’s important to understand the strengths and weaknesses of each. That’s what the rest of this guide is about.

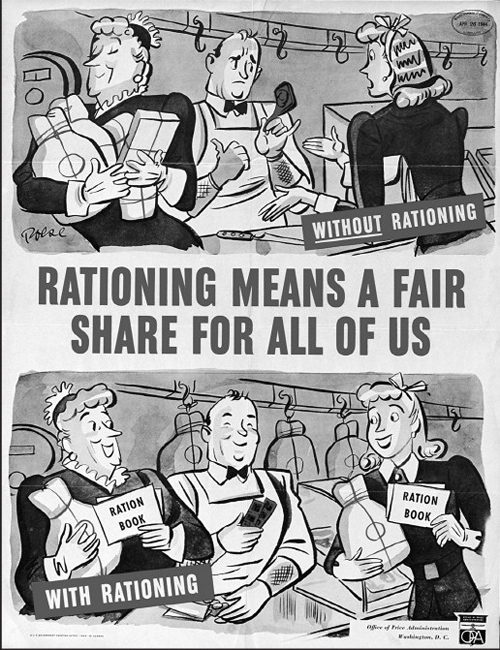

Food and gas were rationed during both World Wars, with everyone receiving equal shares. Courtesy Northwestern University Library.

Fairness is one of the most important principles a climate solution should embody. But what exactly is it?

There are many dimensions to fairness. For example, there’s interspecies fairness: Are we humans being fair to other species?

There’s international fairness: Are we in America, who have emitted more greenhouse gases than any other country, being fair to the rest of the world?

There’s inter-generational fairness: Are those living today being fair to their children and grandchildren?

And there’s intra-generational fairness: If a policy enriches a small minority, while placing burdens on everyone else, is such a policy fair to our fellow citizens?

Fairness must be built in from the outset or it won’t happen.

The key test for interspecies, international, and intergenerational fairness is: Will this policy reduce U.S. emissions fast enough to prevent planetary catastrophe? If not, we have to try harder.

The key test for intra-generational fairness is: Does this policy share the burdens and gains of curbing climate change more or less equally?

During World War II, the draft applied equally to all males, and rationing meant the same shares for everyone. Fairness wasn’t an afterthought; it was built into our policies from the outset.

That should also be true in tackling the climate crisis. It’s up to us to make it happen.

If you wanted to dump harmful waste on your neighbor’s property, you couldn’t do so. Your neighbor would tell you to stop. If you persisted, you could be prosecuted for trespassing.

Alternately, your neighbor could let you dump your waste, but charge you a price for doing so. Either way, you’d have to listen to what your neighbor said.

With the atmosphere, however, things don’t work that way. If you dump carbon dioxide into the sky, no one tells you to stop, no one prosecutes you, and no one charges you a penny.

Why is the atmosphere different from your neighbor’s property? Because no one effectively owns the atmosphere.

The atmosphere is different from private property—it’s a commons belonging to all.

But should, or could, anyone own the sky? And if so, who should it be?

The atmosphere is different from private property—all living beings share it, which makes it a commons. But that doesn’t mean its use can’t be limited.

As it turns out, it’s entirely possible to use property rights and prices to limit use of the atmosphere. But the fact that the atmosphere is a commons means we have to design these tools carefully. We have to make sure that, if the atmosphere is “propertized,” the value of those property rights is equitably shared.

It may be helpful to think of the atmosphere as a parking lot for carbon dioxide emissions. In any parking lot, when demand for parking exceeds capacity, we limit use to short time periods and install meters. If the lot is owned by a public entity, the money paid by parkers is used to benefit all.

In the case of our shared atmosphere, we must also limit parking and charge for it. And, the money polluters pay should benefit all.

Public policies don’t arise in a void. They emerge from a political process that’s driven by players. As in any competition, it helps to know who the players are. In climate policy, there are four key contenders:

• Legacy industries

• Sunrise industries

• Environmental groups

• Everybody else

The legacy industries are the oil, coal, gas, auto, and electric industries. Their interests aren’t identical, but in general, they want to reap maximum return from their past investments and the resources they control. They’re happy with the status quo and favor the least demanding changes. Because they’ve been around a long time—and have lots of money—they enjoy enormous political clout.

The sunrise industries include wind, solar, and some hi-tech companies, plus venture capitalists, investment bankers, and carbon traders. They’re comfortable with change and hope to profit from it. In general, they favor subsidies for energy alternatives and lots of carbon trading. But they have less political clout than the legacy industries.

Environmental groups represent, in theory, future generations and the planet as a whole. In reality, they differ substantially in their tactics and alliances. Some prefer market-based policies, others favor government regulation and spending. Some will make deals with polluters, others won’t. Overall, their effectiveness in Washington has declined since the 1970s, though lately they’ve gotten aggressive on climate change.

Fossil fuel industries favor the least demanding changes.

The “everybody else” category is where most of us fit in. We don’t own stock in Exxon or a wind company; we do drive cars, pay energy bills, and vote. We want climate solutions that are fair and effective and don’t empty our bank accounts. To get that outcome, however, we must make our voices heard. Our disadvantage is that we’re poorly organized, but the Internet gives us a boost. At the end of this guide you’ll find several ways to connect with climate policy groups through the Internet. Please check them out.

The bottom line in climate policy—as elsewhere—is simple: Unless the public puts pressure on politicians, special interests will rule.

Every public policy has winners and losers. Sometimes it’s obvious who those are, but more often, it takes some digging to understand how the money flows.

The typical way special interests get money from government is through subsidies and tax breaks. In those cases, all taxpayers pay, and favored companies gain. The wealth transfers can be seen in public budgets.

Subsidies and tax breaks are very much on the table in climate policy debates. In some cases, when they help sunrise industries, they may be good public policy. But climate change presents several opportunities for businesses to enrich themselves at public expense, and citizens must watch carefully.

In the future, polluters should pay and the public should benefit.

For example, one proposal to cap carbon emissions would give polluting companies free emission permits worth billions of dollars. Other proposals would create a loosely regulated system of carbon offsets that would help traders profit, but add uncertain public benefit.

The big question in climate policy is whether polluters should pay pollutees, or vice versa. If carbon permits are given free to historical polluters, energy prices will rise and we’ll all pay more to whoever gets the permits. That wealth transfer—which over time could exceed a trillion dollars—will flow straight from our pockets to the shareholders of private companies. It will be less visible than tax-funded transfers, but a huge shift of wealth nonetheless.

If rewarding polluters is the wrong way to go, the right way is just the reverse. In the future, polluters should pay and the public should benefit. And with good policy that can happen.

The climate crisis won’t be solved with the stroke of a pen. Whatever legislation is passed will take decades to implement. During this time, political support for reducing emissions must remain high.

For climate policy to work, it must be effective for forty years or more.

So it’s important to think about political dynamics. What happens when energy prices rise? What happens if a different party comes to power? How likely is it that the initial policies will stay on course?

A look at American history shows that lasting policies have support from (a) the middle class, or (b) powerful industries. Social Security lasted but the War on Poverty didn’t because the former is widely backed by the middle class and the latter wasn’t. Subsidies for oil and coal lasted but subsidies in the 1970s for solar and wind energy didn’t because the former industries sway more votes in Congress than the latter.

Will the middle class support carbon reductions for 40 years? In large part that depends on who pays whom. If the middle class ends up paying big energy companies, its support will quickly fade. On the other hand, if the middle class gets a fair deal, its support stands a good chance of lasting.

Our technologies got us into this mess, so it’s natural to wonder if technology can get us out.

The answer is that technology is part of the solution, but not the whole solution, and not what will drive the solution. Rather, better technologies will emerge when the market and government flaws are fixed.

Most of the technologies we need are already known.

The other truth is, we can’t count on a magic techno-fix to rescue us from climate change. Most of the technologies we need to meet our climate goals are already known. The challenge is bringing them to scale. That scaling up can be speeded by public policies, and as that’s done, the prices of these technologies will come down.

Here are some other things to understand about technologies.

Fossil fuels are unique

There’s no other source of energy that’s as concentrated and convenient as fossil fuels. This means we can’t simply replace fossil fuels with something else. We also have to use less energy, and use it smarter.

Solar, wind, and tidal power

Solar, wind, and tidal power—like the power of falling water—are free gifts of nature. We’ve made great strides in harnessing them efficiently. Their chief problem is that they’re intermittent and spread out. To take maximum advantage of them, we need a smart electric grid that can move these kinds of power from where they’re harvested to where electricity is needed.

Hydrogen

Hydrogen isn’t a source of energy—it takes energy to make it. (It has to be extracted from water or fossil fuels.) Its value is that, once made, it can be stored, transported, and used without emitting greenhouse gases.

Hydrogen’s usefulness depends on how it’s made. If we have to burn carbon to get it, it won’t help.

Hydrogen’s usefulness as a climate solution depends on how it’s made. If it’s extracted from water using solar, wind, or tidal power, it will be a boon. If we have to burn carbon to get hydrogen, it won’t help much at all.

Nuclear energy

Scientists once thought nuclear power would be “too cheap to meter.” It didn’t turn out that way. Nowadays, nuclear power is hugely expensive and exists only because of subsidies.

Nuclear energy has another big problem: safety. It’s not just that a plant can get out of control (as at Three Mile Island and Chernobyl). It’s also that the wastes from nuclear plants are radioactive—and stay that way for thousands of years. On top of that, the same materials that fuel nuclear power plants can be used for bombs. A world with thousands of nuclear power plants would be a dangerous world indeed.

Biofuels

Biofuels are liquid fuels made from plants—ethanol (grain alcohol) and bio-diesel (made from vegetable oil) are best known. They require energy and chemicals to produce, and they emit carbon when burned (though less carbon than fossil fuels). In theory, biofuels can be made from non-edible plants grown on land not suitable for food production, and such new forms of farming should be promoted. But if demand for biofuels rises, it will be hard to stop food farmers from diverting land, water, and other resources to biofuels. That will drive up food prices and raise the question of whether we would we rather drive or eat.

Geo-engineering

Some clever people want to scatter iron filings on the oceans to stimulate growth of phytoplankton. In theory, these oceanic plants would absorb carbon dioxide from the atmosphere. The trouble is, they’d also disrupt marine ecosystems, with unforeseeable consequences.

Other tinkerers would fill the sky with reflective particles that, in theory, would reduce the amount of solar radiation reaching the Earth.This too carries great risks.

The problem with all geo-engineering schemes is that they could take us from the frying pan into the fire. When internal combustion engines were invented, no one imagined they’d disrupt the climate. Similarly, when coolants like Freon were introduced, no one suspected they’d dissolve the Earth’s ozone shield. The truth is, we know so little about the Earth’s systems that we could easily trigger another disaster by pursuing these strategies on a large scale.

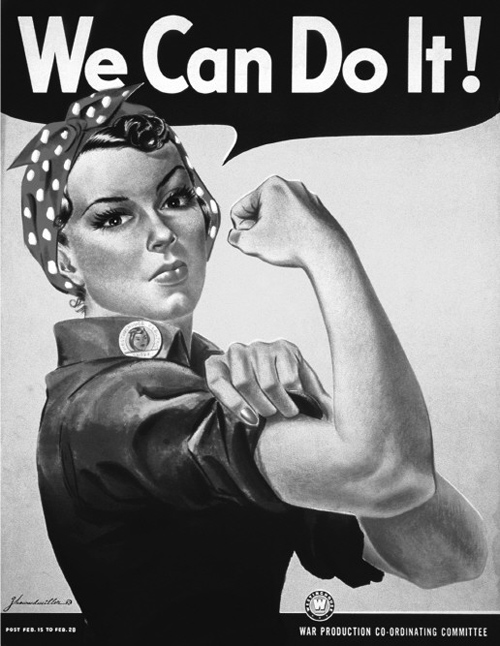

There’s no doubt that, once Americans make up our minds, we can rise to almost any challenge. During World Wars I and II, we drafted men, sent women into factories, raised taxes, and rationed commodities such as oil and food. In both cases, we not only won the wars but gave our economy huge boosts.

Solving the climate crisis won’t require the same degree of mobilization as the two World Wars did, but it will require a new, economy-wide system for limiting our use of the atmosphere, and new priorities for public investment.

Fortunately, if designed right, these climate solutions can be good for our economy. They can spur investment, create jobs, and lift millions out of poverty.

The challenge is to make the necessary fixes and keep them in place for 40 years.

Courtesy Wikimedia Commons.