Because of the poor leadership of the top military officer inside Fort Mims, the settlers were completely unprepared for the Indian attack when it came. Doy Leale McCall Rare Book and Manuscript Library.

Chapter 2

THE MASSACRE AT FORT MIMS

The sound of drums announcing the noon mealtime in crowded Fort Mims also was the signal for some two hundred Creek Indian warriors who had been hiding all morning in thick vegetation close to the hastily constructed stockade.

The warriors now sprinted toward the wide-open eastern gates, swiftly but silently, war clubs, tomahawks and a few rifles in hand.

The date was August 30, 1813. Although several hundred area settlers and soldiers had holed up inside the fort more than a month earlier for protection against rumored Indian attacks, the defenders could hardly have been less prepared. The outer gate on the western side of the stockade was unbolted, and both gates on the eastern side were open. The soldiers were hungover after a night of whiskey and whimsy.

The sentry charged with watching the horizon for signs of Indians instead was looking over his shoulder at a card game. He did not spot the invading force until the warriors were thirty steps away. When he finally did spy them, it was too late.

“Indians!” the guard yelled, shooting his musket in the air. “The Indians! The Indians!” The warning set off panicked confusion in the camp. Men scurried for their weapons. Major Daniel Beasley, the man in command of the fort’s defenses, raced to shut the massive outer gate. But it had been open for weeks, and rainstorms that frequently batter the Mobile area during the summer months had pushed a wall of dirt against the gate.

Because of the poor leadership of the top military officer inside Fort Mims, the settlers were completely unprepared for the Indian attack when it came. Doy Leale McCall Rare Book and Manuscript Library.

Unable to budge it, Beasley quickly found a horde of Indians upon him and suffered a gunshot or a blow to the stomach from a spiked war club. Trampled and dazed, Beasley managed to crawl behind the gate and yell to his men to make a stand just before he died.

The ensuing battle raged all day long. When it was over, it had become the bloodiest massacre of American civilians in U.S. history up to that point. Hundreds on both sides died, and the conquering Creeks brutally bludgeoned women and children among the survivors, and claimed some 250 scalps as trophies.

A Mobile Daily Register article in 1884 recounted the massacre from the perspective of a 105-year-old black man named Tony Morgan, who claimed to have been a slave of Judge Harry Toulmin. He told the newspaper that he was inside the fort at the time of the attack. He recalled an officer from Fort Stoddert warning of an imminent Indian attack.

That warning, according to the newspaper, went unheeded.

“After the entrance of the Indians into the fort, the most horrible butchery was committed,” the article states. “Men, women and children were brained without mercy by the Indians using tomahawks.”

Fort Mims started simply as the home of Samuel Mims, a Virginian who had come by way of North Carolina to what eventually would become the Mississippi Territory. He had spent some time in Creek country, loosely confederated tribes with a combined population of eighteen to twenty-four thousand over much of what now is Alabama and western Georgia.

Mims left after the decline of the deerskin trade, signed an oath to the Spanish crown in 1787 and, the following January, married Hannah Raines of St. Augustine in a Catholic wedding.

A decade of land speculation along the Tombigbee River and the northern edge of the city of Mobile made him wealthy. In 1797, Mims acquired 524 acres near Boatyard Lake close to the modern-day village of Stockton, about thirty-five miles northeast of Mobile.

A Spanish census shows him to have had 150 barrels of maize, sixteen slaves, ten horses, ninety cattle and one hundred pounds of tobacco in 1786. The following year, his holdings had grown to 250 barrels of maize.

While overseeing slave plantations, he also went into the ferry business. It became quite lucrative after Congress created the Mississippi Territory in 1798 and authorized the construction of Fort Stoddert in Mount Vernon, north of Mobile, in 1799. That made the ferry crossings of Mims and Adam Hollinger the preferred route across the Delta for westbound pioneers. Benjamin Hawkins, the principal U.S. representative to the Creek Indians, issued up to one hundred passes a month to pioneer families.

As the population of white settlers grew, relations with the neighboring Indians soured. During the 1780s and 1790s, Creek warriors raided settlers’ plantations, stealing horses and slaughtering cattle.

By 1804, the region numbered some two hundred pioneer families, including fifty to sixty on the east side, known as the Tensaw settlement. President Thomas Jefferson’s public lands commissioner, Ephraim Kirby, held the settlers in low regard. In a report to Washington, D.C., he wrote that the inhabitants, with few exceptions, were “illiterate, wild and savage, of depraved morals unworthy of public confidence or private esteem, litigious, disunited, and knowing each other, universally distrustful of each other.”

The administration of justice, in Kirby’s words, was “imbecile and corrupt,” and the militia was “without discipline or competent officers.”

Recent arrivals from the States “are almost universally fugitives from justice, and many of them felons of the first magnitude.”

Circumstances, however, eventually would force these ragtag settlers together. Indian raids over the next decade grew, as did sentiment within the Creek nation for an all-out war to expel the white interlopers.

In response to the threat of violence, Mims built a palisade compound around his home. Toulmin, the superior court judge for the Tombigbee District of the Mississippi Territory, wrote on July 23, 1813, of the panic gripping the region: “The people have been fleeing all night.”

The conflict reached a boiling point in the summer of 1813. A band of Creek warriors obtained guns from their Spanish allies in Pensacola, alarming the Americans. U.S. officials decided to launch a preemptive strike; forces took the Indians by surprise during their mealtime at Burnt Corn Creek on July 26.

The confrontation ended with a retreat of American forces, but not before they inflicted serious damage on the Indian war party. Reports of American atrocities enraged the Creek nation, prompting the Redstick warriors to return to Pensacola and rearm.

That month, some 400 to 550 people crowded into Fort Mims. They included settlers and about 100 slaves, as well as soldiers from the Mississippi Territorial Volunteers and the local Tensaw militia—plus fifty or more children and dozens of dogs. Samuel Mims was sixty-six at the time.

The settlers and the Creek Indians were closely intertwined. The fort’s residents included friendly Indians and mixed-race people with Indian and white parents. These so-called métis had friends and relatives among the Redsticks who launched the attack.

Conditions were cramped. The entire compound was only one and a quarter acres. It included seventeen buildings, among them an unfinished blockhouse on the southwest corner and a log palisade. About twenty white métis families lived in hastily constructed log cabins. Mims and his family shared their house and possessions.

The soldiers, meanwhile, lived in tents along the northern and eastern double walls.

Outhouses, rows of bee gums (beehives made from hollow trees), cabins and shelters covered the rest of the space.

In the center was the Mims house, itself, a single-story frame structure, unusually expensive for the time.

The mass of people and animals living in close quarters for weeks led to illness, the primary treatment of which was an extra gill (equal to a quarter of a pint) of whiskey and bleeding. Weeks without Indian sightings, combined with shrinking supplies, helped contribute to the complacency that fully enveloped the camp by the day of the attack. Some settlers began leaving the fort to search for wild berries. Others returned to their farms or bought food from those with extra supplies.

In retrospect, the men charged with defending Fort Mims had plenty of warning of an imminent attack. General Ferdinand Claiborne, the commander of Fort Stoddert, inspected Fort Mims on August 7 and found its readiness wanting. He ordered Beasley to fortify the pickets and build more blockhouses, an order that apparently went unheeded.

In the days leading up to the attack, Beasley received several reports of Indian sightings but chose to discount them.

A slave of Zachariah McGirth named Jo—one of three captured and interrogated by the Redstick Indian force—escaped and carried warnings to Fort Mims. Beasley gave them no credence.

A pair of slave boys reported seeing Indians on August 29, the day before the attack. But when a patrol sent by Beasley turned up no signs of the Creeks, the commander ordered one of the boys whipped. The following morning that same boy and a slave owned by settler John Randon reported seeing Redsticks within a mile of the fort as they were tending to cattle.

A scout, James Cornells, rode to the east gate on the morning of August 30 and shouted to Beasley that he had seen thirteen Indians in the woods a short distance from the fort. Beasley—who Cornells later recalled appeared to be drunk—said Cornells must have seen a gang of red cattle.

“That gang of red cattle will give you a hell of a kick before night,” Cornells replied.

Beasley ordered Cornells arrested, but he avoided apprehension by riding off for Fort Pierce.

Inside Fort Mims, men sat in two circles discussing what they might do if an Indian attack did come. Someone played the fiddle. Beasley oversaw the flogging of Randon’s slave, who had reported danger.

Josiah Fletcher, the owner of another slave who had reported seeing Indians, believed the man. He refused to allow Beasley to discipline him, prompting the angry major to order Fletcher and his family to leave the fort by ten o’clock the next day. Reluctantly, Fletcher backed down and allowed the slave to receive a lash.

Again spotting Indians after he was sent out to herd cattle on the morning of the attack, Randon’s slave fled for Fort Pierce rather than risk another beating.

At ten o’clock that morning—two hours before the assault—Beasley sent his final dispatch to Fort Stoddert. In it, he reported 106 soldiers of the First Regiment of the Mississippi Territorial Volunteers, including 6 on leave to Mobile. The defense also included 41 or 42 militiamen.

Beasley declared his men fit for duty and expressed no concern for the preparedness of the fort, even as hundreds of Redsticks at that moment were surrounding the compound in secret. He alluded to the reported Indian sighting but dismissed it.

“Sir, I send enclosed morning reports of my command,” the dispatch states. “I have improved the fort at this place and made it much stronger than when you were here…There was a false alarm yesterday…But the alarm proved to be false.”

Beasley boasted of his ability “to maintain the fort against any number of Indians.”

Responsibility for drawing up the battle plan on the Creek side fell to William Weatherford, a strapping man in his thirties who had grown up with one foot in the Indian world and another in the white one. His mother, Sehoy III, was a member of the influential Wind clan of the Creek people. His father, Charles Weatherford, was a red-haired Scotsman who had ridden into the Upper Creek territory with Samuel Mims in 1779 or early 1780 to escape the Revolutionary War.

Creek society was matrilineal, meaning inheritance and family identity passed through mothers, not fathers. By marrying Sehoy, Charles Weatherford gained a measure of status. He participated in Creek council meetings and trafficked in stolen horses and slaves.

In Creek society, because of the matrilineal structure, maternal uncles shared closer bonds with children than the biological fathers. As a result, Creek Indian chief Alexander McGillivray played an important role in William Weatherford’s upbringing. By 1787, McGillivray owned a thriving plantation in the community of Little River, situated in the northernmost section of Baldwin County, Alabama.

William Weatherford, whose father was Scottish and mother was Creek Indian, planned the attack on Fort Mims in 1813. Doy Leale McCall Rare Book and Manuscript Library.

Charles Weatherford spent a year in a Spanish jail in New Orleans over an unpaid debt and subsequently sought to undermine Spanish rule and McGillivray’s own diplomacy. After McGillivray’s death in 1793, Charles Weatherford worked to promote stronger Creek ties with the United States.

Weatherford in 1803 helped Benjamin Hawkins, the U.S. government agent in the Creek territories, apprehend British loyalist William Augustus Bowles, who had attempted to lead the Creeks to form an autonomous Muskogee nation. William Weatherford assisted in the capture when Bowles tried to address the National Creek Council at Hickory Ground.

William Weatherford thus had divided loyalties. But he held deeply to the traditionalist religious beliefs espoused by the prophets who urged violent confrontation with the Americans and turned away from his European side.

Until the day he died in 1824, Weatherford regretted his role in the attack on the fort, which housed some of his own relatives. He had worked to limit the carnage that would result from the sneak attack.

“Tomorrow, I will lead you into battle,” he told his men on the eve of the attack. “I go to fight warriors, not squaws. A Creek warrior gains no merit in spilling the blood of a squaw. The women and children should be spared. They can be carried back to the nation and serve the red man as servants.”

If Weatherford was a reluctant warrior, however, he held nothing back as a tactician. The successful attack caused his legend to grow over the ensuing decades. According to an 1858 letter by an acquaintance, Thomas S. Woodward, Weatherford went by the war name Hopnicafutsahia—Truth Maker or Teller. Another moniker was Billy Larney, which translates to “Yellow Billy.”

One hundred years after the massacre at Fort Mims, Alabama commemorated the event with a historical marker. Doy Leale McCall Rare Book and Manuscript Library.

In 1855, decades after Weatherford’s death, he acquired yet another name—Lamochattee, or Red Eagle. The work The Red Eagle: A Poem of the South sprang from the pen of Alexander Beaufort Meek, a lawyer and accomplished chess player who one day would become Alabama’s attorney general.

Some historical accounts of the Massacre of Fort Mims refer to Weatherford by this name, but modern historians have indicated that he likely never went by that title in life.

Weatherford’s battle plan called for sending an initial wave of two hundred warriors through the open eastern gate, and while they occupied the settlers’ defense, following up with additional forces assaulting the fort from the west, south and north.

The Redsticks gained valuable intelligence from the three captured slaves, who indicated the fort’s commanders believed there was no threat of an Indian invasion. Weatherford harbored doubts that the defenses could be so lax and stole close to the fort to have a look for himself.

Convinced that the fort, indeed, was ripe for assault, Weatherford rode toward Boatyard Lake after midnight and took up position about three quarters of a mile from the fort.

On the morning of August 30, the women in the stockade began preparing breakfast and the scent of frying bacon and biscuits wafted into the warm, humid air. Two hundred Redstick warriors under the command of Peter McQueen made their way to a ravine about two hundred yards from the gate and waited for the signal to attack.

The men, some painted red and black and naked except for their loincloths, took the fort by surprise. Nehemiah Page, a Territorial Mississippi Volunteer who was sleeping off a hangover in the horse stables outside the fort, saw the approaching warriors and watched through a gap in the wood.

“It is impossible to imagine people so horribly painted,” Dr. Thomas Holmes, the fort’s assistant surgeon, later recounted.

Page ducked out of sight until the Indian invaders had passed him and then jumped out of the stable and ran for his life toward the Alabama River. A little dog that had come with the Indians turned after seeing Page and then started running after him. Reaching the river, Page dove into the water, the dog closely behind him. The dog, sometimes in his wake, sometimes at his head, helped Page reach the other side. Exhausted, he finally made it to the safety of the white settlements.

After that, Page would never leave the dog’s side.

Inside the fort, meanwhile, four feather-clad Indians chosen by the prophet Paddy Walsh sprinted past the fallen Major Daniel Beasley and swung their clubs without fear or mercy. They had been told by Walsh that they were impervious to the white man’s bullets. Walsh had predicted that no more than three Creek warriors would die that day.

The Redsticks were not immune to bullets, however, and three of the four quickly died. The fourth, Nahomahteeathle Hopoie, retreated.

Under loud war whoops, the battle was on. Redstick warriors poured through the eight-foot-wide gate and engaged soldiers in fierce hand-to-hand combat as bodies piled up. Between the inner and outer gates, half of the Mississippi Territorial Volunteers died within the first few minutes of the battle.

Dixon Bailey, the commander of the Tensaw militiamen, rushed toward Tenskwatawa, the Shawnee prophet, and shot him dead. His men hacked the fallen Indian to pieces.

As the battle raged, Weatherford blew a whistle hanging from his neck, a signal for the second wave to begin. Warriors advanced on all sides and fired a sustained barrage of arrows and bullets at the fort. The attackers were able to easily seize most of the portholes meant for the fort’s soldiers to fire at the invaders from safety.

This was because of one of the many deficiencies of the fort. The portholes were only three and a half feet above the ground, without a protective ditch or bank. A properly designed fort would have placed them much higher, putting them out of reach from the other side and allowing defenders to fire from an elevated position. Instead, the Creeks seized the advantage, using those portholes to fire inside the fort. At times, both militiamen and Indians jammed guns inside the same holes and fired simultaneously.

Mississippi Territorial Volunteers Captain C. Hatton Middleton led a counterattack at the east gate while Captain William Jack defended the pickets on the southern side. During the fierce fighting at the gate, Middleton and most of his men perished. Jack, too, died early in the fighting.

The fort’s women took up the defense, loading muskets and rifles and handing them to the remaining men. According to an account by nineteenth-century lawyer and historian Albert James Pickett, “The women now animated the men to defend them, by assisting in loading the guns.”

Indians attacking from the west side found the inner gate barred shut. They scaled the wall and took over the unprotected blockhouse on the southwest corner of the fort.

Directing the assault from the northern wall, Weatherford sent 150 Creek warriors at Bailey’s men, who offered the fort’s stiffest resistance. The Redsticks would dive to the ground, reload and spring to their feet to fire.

Bailey, himself a métis, knew that Creeks historically fought only in short spurts and reasoned that he could defend the fort if he and his men could manage to hold out long enough.

By 2:00 p.m., the Creeks and settlers had been fighting for two hours. In the bastion, where Bailey’s men had holed up, blood was shoe deep. Some three hundred Indians had died mostly along the north side portholes.

The Redsticks withdrew and convened a council at the cabin of a Mrs. O’Neal on the Federal Road northeast of the fort. The participants elected Weatherford to take over for the Far-off Warrior, Hopoie Tastanagi (or Hopvye Tustunuke). A debate ensued over whether the Creeks had sufficiently humbled the settlers or whether they should return and go for total destruction.

During the lull, soldiers at the fort hit the whiskey barrel.

After about an hour, the Redsticks renewed the battle, this time launching flaming arrows into the fort. The roof of the smokehouse caught fire, as did the roof of the kitchen and other nearby structures. Indian warriors chopped down the western gate.

James and Daniel Bailey, brothers of Tensaw militia commander Dixon Bailey, went with other men to the attic of the Mims house—the highest point in the compound—and rained gunfire at the Creeks in the fields north and south of the fort.

Wave after wave of Redsticks charged Patrick’s Loomhouse, a still intact building on the property, stumbling over the corpses of fallen comrades. Thwarted, the remaining men broke off the attack and joined Creek warriors elsewhere in the fort.

The back gate fell, and Weatherford led a group of warriors into the fort. Susannah Hatterway, the Creek wife of one of the American settlers, later reported watching Weatherford gracefully leap over a pile of logs nearly as tall as his six-foot-two frame. He shouted, “Dixon Bailey, today one or both of us must die.”

Now five hours old, the battle continued among the exhausted combatants. The Indian fighters continued to launch flaming arrows at the Mims house, where most of the women and children had gone. As the structure caught fire, their screams rose above the war whoops. The fire-weakened roof finally collapsed, dragging the Bailey brothers to their deaths and crushing dozens of women and children inside.

In 1847, Dr. Holmes recalled the horror and carnage from that bloody afternoon three decades earlier. “The way that many of the unfortunate women were mangled and cut to pieces is shocking to humanity, for very many of the women who were pregnant had their unborn infants cut from the womb and lay by their bleeding mothers,” he wrote.

Survivors headed toward the bastion. An account by historian Albert James Pickett in 1851 put it this way: “Soon it was full to overflowing. The weak, wounded, and feeble were pressed to death and trodden under foot. The spot presented the appearance of one immense mass of human beings, herded together too close to defend themselves, and, like beeves in the slaughter pen of the butcher, a prey to those who fired upon them.”

Frenzied Redstick warriors slaughtered the armed and helpless, alike, with tomahawks and knives. David Mims, Samuel’s seventy-six-year-old brother, fell from a powerful blow from a club, which opened a large hole in his head. Gushing blood, with one of his last breaths, he said, “Oh God, I am a dead man.”

An Indian warrior lifted his head and cut his scalp.

Dixon Bailey, concluding that the battle was lost, now urged people to try to escape. “All is lost,” he said. “My family are to be butchered.”

Fire spread from building to building. The powder magazine exploded, sending debris and ash into the sky.

A few of the remaining settlers made it through a gap in the pickets, but most died. Indian warriors killed some of the people who did manage to flee the fort. The assistant surgeon, Dr. Holmes—who also was a private in the Mississippi Territorial Volunteers—fled with a slave named Tom carrying Dixon Bailey’s severely ill teenage son. The slave turned around and returned to the fort, handing over the boy to the Creek warriors, who killed him with a knife.

Thirteen soldiers intended to make a stand in the open to help civilians escape, but they scattered under heavy fire.

A slave woman named Hester made it to Fort Stoddert and gave the first account of the massacre.

Children and women lay in mangled heaps. Redstick warriors stripped and scalped the women and dismembered the victims. They cut unborn children from their mothers. A soldier named Rushbury reportedly died from fright.

Creek warriors questioned Dixon Bailey’s sister, who pointed to James Dixon’s body and said, “I am the sister of that great man you have murdered there.”

The warriors then knocked her down, cut her open and emptied her insides. They threw some of the corpses, as well as some of the wounded, into the fire.

Susannah Hatterway took four-year-old Elizabeth Randon in one hand and a young slave girl in the other and led the terrified children into the open.

“Let us go out and be killed together,” she said.

Efa Tastanagi, the so-called Dog Warrior, recognized Hatterway as a woman who had been like a surrogate mother to him. He stepped in front of a group of fellow Creek warriors and prevented them from killing the woman and children.

Weatherford’s half-brother, David Tate, later told his son-in-law, “As soon as he was satisfied…that the Fort would fall…he rode off, as he had not the heart to witness what he knew would follow, to wit, the indiscriminate slaughter of the inmates for the Fort.”

Just before five o’clock in the afternoon, the killing finally stopped. The Creek warriors took Hatterway and the two girls, along with other women and children, prisoner. The bounty included about one hundred captured settlers, two hundred or more scalps, horses and other property.

Half of the Indian force, however, lay dead, disabled or wounded.

The blockhouse and adjacent sections of pickets were the only parts of the fort that escaped the fire. Days later, U.S. troops buried 247 bodies at the fort. Major Joseph P. Kennedy, in a report to General Claiborne, described the toll: “Indians, negroes, white men, women, and children lay in one promiscuous ruin. All were scalped, and the families of every age, were butchered in a manner which is neither decent nor language will permit me to describe.”

The brazen attack heightened alarm throughout the region. Fearing another Indian assault, authorities evacuated women at Fort Stoddert to Mobile. Judge Toulmin, who could see signs of the battle from the safety of that installation, offered a highly critical assessment of Beasley’s performance.

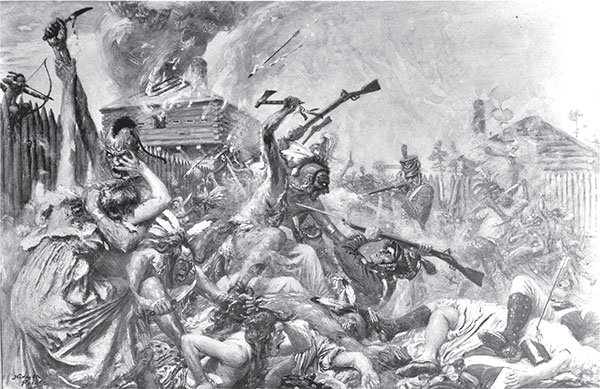

The battle inside Fort Mims raged until near five o’clock in the afternoon. By then, hundreds on both side lay dead or wounded, and most of the buildings inside the compound had been destroyed. Doy Leale McCall Rare Book and Manuscript Library.

“It was but this morning that Major Beasley wrote down that he believed that the indications of the approach of Indians, of which he had recvd. on account, was unfounded and at noon he was vigorously assailed at Fort Mims on Tensaw by a considerable body of them,” Toulmin wrote on the evening of August 30. “What the result is we do not know, but the smoke of burning houses in that quarter are now seen on the river bank at Fort Stoddert.”

In the aftermath of the fighting, General Claiborne praised Beasley’s bravery and that of his men.

“Never [have] men fought better,” he wrote.

But Claiborne also wrote that “such was the advantage given to the enemy, by neglecting the most obvious precautions, all their bravery was thrown away…Had the gates been kept closed, and the men properly posted…all experience shows that such a force might have kept at bay a thousand Indians.”

The Creek victory at Fort Mims was a costly one. Historians estimate more than half of the Redstick warriors died during the battle; many others would later succumb to wounds they suffered during the fight.

More importantly, it sparked the Creek Indian War, which ended with the Indian defeat at Horseshoe Bend on March 27, 1814, by the superior American Army led by Major General Andrew Jackson. That battle followed a string of victories that Jackson rang up at Tallassee, Talladega, Hillabee and Tallaseehatchee.

The Redsticks surrendered with the Treaty of Fort Jackson on August 9, 1814, forfeiting forty thousand square miles to the Americans. It was a prelude to one of the darkest chapters in American history, the forced relocation known as the “Trail of Tears” of tens of thousands of Indians to lands west of the Mississippi River.

The assault on Fort Mims had convinced many Americans that peaceful cohabitation among the Indian tribes in the western territories was impossible.

Speaking for many of his countrymen, Jackson said, “We must hasten to the frontier, or we shall find it drenched with the blood of our citizens.”