This is a document related to the coroner’s inquest into the murder of Nathaniel Frost in 1834. Mobile County Probate Court records.

Chapter 3

THE MURDERER AND THE OAK TREE

At half past one o’clock in the afternoon on February 20, 1835, the jailer rapped on the door of the cell where Charles R.S. Boyington had spent the last nine months chained to a wall. The young man had been dreading this day ever since a Mobile County judge sentenced him on November 29, 1834, to die for the brutal slaying of his friend and roommate, Nathaniel Frost.

Even as the jailer led him to the procession that would carry him to his death, Boyington held out faint hope that he might yet somehow avoid his fate. He asked the jailer if the governor, perhaps, had arrived.

He had not.

Boyington had spent the previous two and a half hours in conversation and prayer with Reverend William T. Hamilton, pastor of Government Street Presbyterian Church, who had spent several mostly fruitless months trying to persuade the condemned man to atone and accept God.

Boyington wrote a letter to his mother and another one to his brother.

Then it was time to march, more than an hour from the big iron gates on the St. Emanuel Street side of the jail north to Government Street, west to St. Charles Street then south a little past Church Street through the area known at the time as Buzzards Roost for the birds that would swoop down for the scraps left by the neighborhood’s butchers.

The route had been chosen so Boyington would have to pass by the spot where Frost’s badly mangled and bloody body had been found the previous May. It was just outside the cemetery where Boyington soon would be buried.

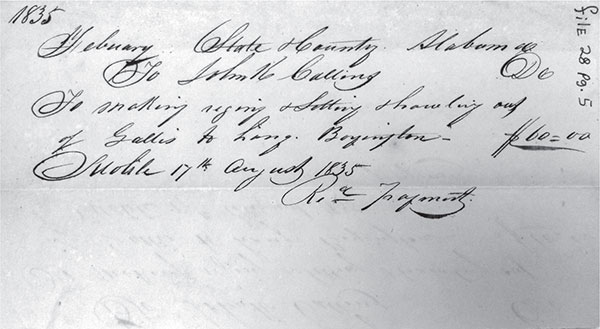

This is a document related to the coroner’s inquest into the murder of Nathaniel Frost in 1834. Mobile County Probate Court records.

Boyington made no last-minute confession, though. He did not move a muscle or change his expression.

The custom of the time held for the condemned to ride atop the coffin. But Boyington received permission to instead walk behind the horse-drawn cart that carried it. He was dressed in a black suit and a fine, silk hat and accompanied by Hamilton and Edward Olcott, one of his lawyers.

A huge crowd had turned out to watch the spectacle and although Boyington occasionally waved to an acquaintance standing at the edge of the sidewalk on Government Street, it mostly was not a sympathetic audience. Few doubted Boyington’s guilt.

A foot troop known as the Home Guards and the City Troop on horseback, each with a brass band, escorted Boyington to the execution spot west of Palmetto Street at four o’clock. He saw the gallows, specially constructed for this day at a cost of sixty dollars, and the color drained from his face.

“If I can succeed in delaying the execution till the appointed hour is passed, will you demand me from the sheriff?” he asked Olcott.

“It cannot be done, sir, the officers will most assuredly do their duty,” the lawyer responded.

Panic gripped Boyington as he stared at the gallows and looked around at the swelling mass of people. The execution had drawn voyeurs from as far as New Orleans and even slaves to watch Boyington’s death.

He tried to stall, reading from a long manuscript he had drafted. “My dear friends, an innocent man will now address you. I tell you with an open heart, that I am innocent of the crime I am accused of. I will not keep you long, but I must tell you that the pain I have been suffering is unjust. I am accused, yes, but I am the man being murdered today. Emotion makes my lips tremble as I address you.”

This bill for services shows that Mobile County paid sixty dollars in 1835 for the gallows used to execute Charles R.S. Boyington. Mobile County Probate Court records.

As the speech dragged on, Sheriff Theophilus Lindsey Toulmin and his deputies became impatient. Finally, the sheriff had heard enough. He ordered Boyington, who had finished barely a third of his address, to stop. He motioned toward Hamilton.

“Mr. Boyington, the sheriff orders you to stop; the time is nearly expired. Ascend with me and calmly submit to the last necessary arrangement,” the minister said.

“What, can’t I read the rest?” Boyington asked.

“No, sir, not another page!” Toulmin said. “I am waiting for you.”

Boyington turned to the surgeon who was to pronounce him dead and whispered, “Will it be possible to reanimate my body after I am executed?”

The surgeon shook his head, “I assure you it cannot be possible.”

“What is the easiest way to die?”

“For the lungs to be moderately inflated,” the doctor answered.

Boyington took off his coat and black tie. Sighing heavily, pale with swollen veins in his neck and temples, he raised his eyes to the heavens. Deputies placed a shroud on him and they walked up the scaffold.

Boyington’s life was about to end.

Not even a year before, Charles R.S. Boyington’s future seemed to hold so much promise. A Connecticut native, he had arrived by ship from New Haven in November 1833 with dreams of starting a new life in what then was one of America’s most exciting cities.

A printer by trade, Boyington worked for a time for Pollard and Dade but found himself laid off in April 1834. Despite the setback in his professional life, his personal life was in good shape.

He was handsome, with a dark complexion and black hair. He had small eyes with large, heavy brows, and he walked with such an upright posture that he appeared taller than his five-foot-nine frame. At a ball held at the Alabama Hotel on Royal Street in December 1833, he met the love of his life, Rose de Fleur, the daughter of a French count who had fled his native country for Mobile. She would stick by him until the end, bringing him flowers and cakes during his incarceration.

Shortly after coming to Mobile, Boyington met Nathaniel Frost, who arrived from Connecticut the same year he did. The two had much in common. In addition to their shared New England heritage, Frost also was a journeyman printer. In Mobile, he worked part time for a newspaper while he tried to recover from tuberculosis.

The two men shared a room at the boardinghouse of Captain William George on Royal Street.

They became virtually inseparable. Boyington brought Frost meals and cared for him through his illness. In return, Frost—who came from a wealthy family—paid his unemployed friend’s room and board and supplied him with spending money.

“What a whole-souled, generous-hearted young man Boyington must be,” said George’s wife.

On the afternoon of May 10, 1834, Boyington and Frost took a walk. Several people saw them near the Church Street Graveyard.

But Boyington was alone when he returned to the boardinghouse at about 3:30 p.m. Several of the boarders asked where Nathaniel was.

“Oh, he is somewhere; I am in a hurry, so I did not wait for him,” Boyington said.

Boyington seemed restless, distracted and slightly pale.

“You went out walking, where is he?” one of the men asked.

“Yes, and I brought him back,” Boyington answered.

Boyington walked to Morris and Fraser’s Livery on St. Francis Street, which sported a sign reading, “Horses for General Hire, By Day, Week or Month, etc.” Boyington paid for a horse and then made his way to the wharves, stopping at a general store to buy a pair of pistols, a dagger and some other items.

At eight o’clock, he boarded the James Monroe, a steamer headed up the Alabama River toward Montgomery.

The next day, passersby discovered Frost’s body under a large chinquapin tree on the west side of Bayou Street, south of Government Street. Covered in wounds and blood, the body had five distinct gashes on the front that investigators determined had been made with a large dirk knife. Frost’s head had bruises, and gashes covered his back, arms and legs, as well. Even in a lawless town that had grown accustomed to robberies and killings, the scene caused a sensation.

“The annals of crime have seldom been stained with a more diabolical act of atrocity than it is now our painful duty at this time to record,” wrote the Mobile Commercial Register and Patriot.

“MURDER—$500 REWARD,” blared the local newspaper the next day. Mayor John Stocking had offered $250 for the capture of Boyington, whom investigators already had fingered as the chief suspect, and another $250 if he was convicted.

Years after the affair, a Mobilian named J.J. Delchamps recalled sitting on the porch as a teenager with his friend James T. Shelton, who would grow up to become sheriff in 1859. Patsy, a twelve- or thirteen-year-old slave belonging to Shelton’s father, came running up the street.

“Masa Jim, when I was looking for the cows a little while ago, I saw two men, a tall one and a short one, fighting under the big chinquapin back of a graveyard,” she said. “They were hitting just so, making motions, the tall man fall down all bloody. I was scared and ran away.”

Shelton asked Delchamps not to say anything; as a slave, Patsy’s eyewitness account would be worthless in court, anyway. Later, Patsy would say that she recognized Boyington at the gallows as the short man she had seen during the fight.

To investigators, Boyington seemed the obvious suspect. Witnesses had placed him with the victim on the day of the slaying. And Boyington’s abrupt departure looked like flight. His reputation did not help. He was known to carouse in the less reputable parts of town near the riverfront, hanging around barrooms, brothels and gambling dens.

He was suspected of thefts in Boston and once was arrested in Savannah and tried on charges of horse stealing in Charleston. He was convicted of piracy there, as well, but won a pardon due to his youth.

Back at George’s boardinghouse, the proprietor’s wife found a neatly wrapped package of books and letters, with a note instructing her to give them to Rose de Fleur.

Having identified Boyington as the prime suspect in the grisly slaying and determined that he had fled town, it was now a race against the steamship for the lawmen. Officers Joseph Taylor and M. DuBois took off on horseback, catching up with the ship at Black’s Bluff some 180 miles north of Mobile on May 15.

The officers found Boyington in the “ladies room” studying the hand of a man playing a card game called brag. Taylor placed a hand upon Boyington’s shoulder. “You are my prisoner,” he said.

“Why?” Boyington asked.

“You are charged with murder,” the officer said, as a look of horror swept across Boyington’s face.

The officers detained Boyington and found that he had a pair of pistols, a wallet, $95 and some silver coins. The large sum of money was suspicious for someone who had not worked in months and never had made more than $20 when he was working. Altogether, authorities estimated, Boyington had not cleared more than $100 during his entire time in Mobile.

Boyington maintained that he had won the money gambling but could not find the person he had bet.

During the return journey, Taylor began to harbor doubts about his prisoner’s guilt and devised a test. He offered to let Boyington go if he left all of his belongings, figuring that an innocent man would not run. Boyington refused. The officer then proposed letting him escape with five dollars. Boyington again refused.

An immense crowd greeted the steamboat when it arrived in Mobile on May 16 with the shackled Boyington. The largely hostile crowd included slaves who were, in the words of a twentieth-century historian, “free for a day.” Many in the crowd followed Boyington as he was taken to the city jail on Theatre Street.

“Kill him,” shouted someone from the throng. “Throw him overboard,” yelled another. “Hang him to the next lamppost—to the next tree.”

The newspaper account was sensational.

“We have never witnessed such an excitement as was manifested on his arrival,” the article stated. “An immense throng rushed to the wharves and the anxiety was intense to obtain a sight of the man charged with having imbued his hands in the blood of his friend.”

Boyington made his first court appearance at ten the next morning for a preliminary hearing that lasted until six in the evening. A judge denied bail.

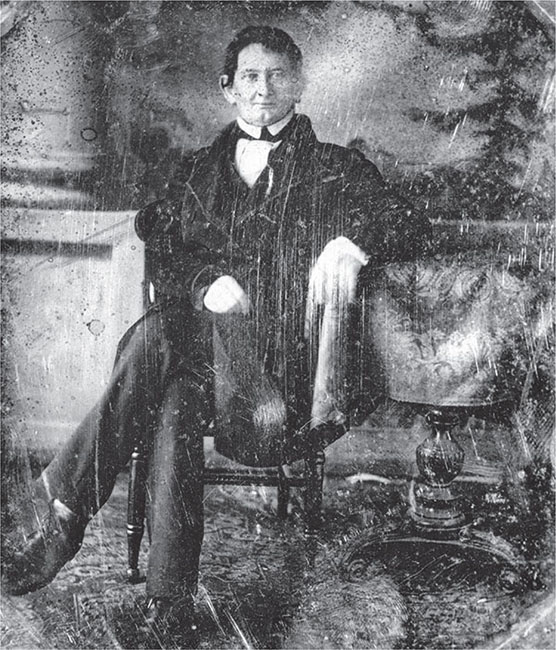

James Dellet, who would go on to serve in the U.S. House of Representatives, helped prosecute Charles R.S. Boyington. Doy Leale McCall Rare Book and Manuscript Library.

By November 16, the state was ready for trial. The prosecutor was Solicitor Berriman Brent Breedin, a short man with a neatly formed, square face. Later, he would find himself on the other side of the courtroom, prosecuted on charges of allowing criminals to escape. He was convicted, but a judge set it aside.

To help him try Boyington, Breedin brought in trial attorney James Dellet, who had served as the first speaker of the state House of Representatives after Alabama became a state in 1819 and later would go on to Congress.

Edward Olcott and Isaac H. Erwin represented Boyington.

The trial lasted until midnight on November 22. After an hour and a quarter, the jury returned with a unanimous guilty verdict. The next day, a Saturday, Judge Samuel Chapman sentenced the defendant “to be hung [sic] by the neck till dead on the twentieth of February, 1835.”

With scarcely a dry eye in the courtroom, officers returned Boyington to jail, shackling and chaining his feet to the wall of his cell.

“Rarely have the feelings of the community been more deeply interested,” the newspaper reported. “The murder was so cold blooded, so unprovoked, and so audacious, and the accused so self possessed, during the whole of the bloody affair, from the crime to the conviction, that wonder, and horror, were mingled with the ordinary feelings of curiosity and excitement on such occasions.”

Boyington’s last realistic hope was an appeal to the Alabama Supreme Court, which had been formed only recently. Prior to 1832, an assembly of circuit court judges considered appeals. That year, the legislature created the Supreme Court as a separate entity,

Boyington cited two main grounds for reversal: improper juror conduct and a defective indictment. A British citizen, George Davis Jr., had been allowed to serve on the grand jury that indicted him, and another juror, Chandler Waldo, had expressed an opinion about the defendant’s guilt. In addition, the defendant argued, the indictment named the accused as Charles J.S. Boyington rather than his actual name, Charles R.S. Boyington.

The court heard the case on February 11, 1835. The court took the first claim most seriously but ended up affirming the conviction. The precedent set by the court did not last long. Two years later, a differently constituted high court, headed by future governor Henry W. Collier, overturned the rule on challenging grand juries.

But the reversal came too late to help Boyington.

Hamilton visited the condemned man in a desperate attempt to save his soul. The justice system had spoken, but if Boyington would make amends and repent, it was not too late to win reprieve from a higher authority.

While Boyington’s brother was a minister, he had no use for religion, himself. But he welcomed Hamilton’s visits as a respite from the solitude of jail.

“I am not offended that you speak so freely. I suppose you will not believe me, and I am sorry for it; but I have no confession to make,” he told Hamilton. “I am not guilty of murder. I have my faults and I have been thoughtless and wild, but of murder I am not guilty.”

Hamilton pressed Boyington, but he maintained his doubts about the existence of God.

“I cannot help it; and where I disbelieve, I am not mean enough to conceal it,” he said in a cold voice.

Hamilton told Boyington that the days were counting down to the time when a noose would be placed around his neck. “In a few short moments after that, your breath will stop, your head will be still, your body dead!” he said. Hamilton urged Boyington to pray with him. Sobbing on his knees, Boyington looked up and said, “I will try, sir.” But Boyington never gave in to the pressure.

“I have been a gay and wild youth. I have been guilty, but not guilty of murder—not guilty of the crime with which report has charged me,” he wrote in a letter to Hamilton. “I swear it by the most solemn oaths that I consider binding.”

In a long statement he had printed defending his innocence, he wrote: “I say that a person who should commit a murder under such circumstances might justly claim a discharge on a plea of idiocy or insanity.”

Charles R.S. Boyington gasped for breath as he looked toward the sky. His court appeal had failed. His hope for a gubernatorial intervention had been dashed. The executioner placed a shroud on him; he ascended the scaffold of the gallows but refused to stand on the drop.

Reverend Hamilton prayed for Boyington’s soul. “Give him strength to make his peace with thee and feel contrite deep down in his heart!”

Boyington grasped Hamilton’s hand. “I thank you, sir, from the bottom of my heart.”

The preacher asked Boyington for his last words. “Sir, I am innocent! I am innocent. But what can I do? When I am buried an oak tree with a hundred roots will grow out of my grave to prove my innocence!”

Boyington’s body stiffened and tears rolled down his cheeks.

“I must make one more effort for my life—I must!”

Boyington leapt off the scaffold and tried to make a run for it. The crowd was aghast.

“Charge bayonets,” the captain of the Home Guard shouted.

Weakened from his months of incarceration, Boyington did not get far. He fell to the ground, as soldiers quickly surrounded him. Daniel Geary, who was in the crowd that day, later recalled that not a single person offered Boyington any encouragement.

“The officers of justice immediately seized him—and then follows the scene that beggars description,” he wrote.

Rose de Fleur had gone to the execution but ran away weeping as lawmen forced Boyington back up the steps. He struggled desperately, but weakly. His bound hands came loose, and he scratched the hangmen and tore at their clothes. The officers readjusted the noose and shoved him off the platform.

It was far from a clean execution.

Boyington somehow managed to get his hands between his neck and the rope. Officers pulled his hands apart. He writhed for half an hour before going limp.

The horrified crowd shrieked at the spectacle.

“Oh, it is like murder!” someone shouted. “It is murder.”

The Mobile Commercial Register and Patriot was unmoved, however. “To the last he made no acknowledgement of his guilt,” the paper reported the next day. “To say the least, however it is a matter of doubt if his harangue to the assembly did not excite prejudice against him, rather than sympathy in his behalf.”

In the decades following the execution, doubt about the justice of it lingered.

After the trial, a man named John Casselle swore out an affidavit maintaining that he had seen Frost—alone—on Water Street at 3:00 p.m. or later on the day of the slaying. If true, that would have proven that Frost and Boyington had separated on Government Street during their walk.

In 1847, under the headline “Wrong Man Hung [sic],” the Albany Evening Journal reported the deathbed confession of the landlord in whose house the murder was committed. One key detail clearly was wrong: the slaying did not occur in a house. Did that make the story bogus, or was it merely a detail confused by time and distance?

J.C. Richardson, a lawyer in Hayneville, Alabama, referenced the Boyington case during his closing argument to a jury in 1894. In attempting to cast doubt on circumstantial evidence, he told jurors a woman named Florence White, having sent for the Mobile police chief, reached underneath her pillow and retrieved a large, gold watch and chain, along with a diamond ring. She confessed that she and her man had followed Boyington and Nathaniel Frost. They waited for their opportunity and then stabbed Frost when he was alone.

The son of Mobile newspaper editor and author Erwin Craighead challenged that account, however, in a letter to the writer of a magazine article recounting the supposed White confession.

In the decades that followed the execution, according to lore, a great oak tree did rise from the spot where Charles R.S. Boyington was hanged. Boyington’s body was buried sixty yards from where a great oak sits today.