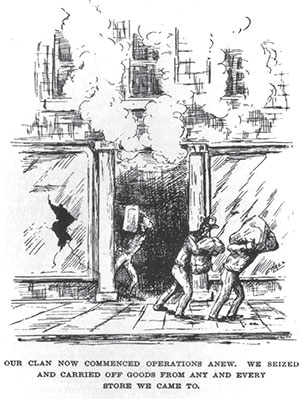

Among other crimes, James Copeland confessed to starting one of the most devastating fires in Mobile’s history in 1839 as cover for looting stores throughout downtown. Doy Leale McCall Rare Book and Manuscript Library.

Chapter 4

THE COPELAND CLAN AND THE BURNING OF MOBILE

As night fell over Mobile on October 7, 1839, a band of men decked out in fake whiskers, false mustaches and other disguises waited at the edge of the city. Some wore green eyepatches; others dressed like sailors. They came armed with false keys, lock picks and crowbars, along with revolvers, bowie knives and dark lanterns.

The men had planned for this night for weeks, casing the city’s commercial district and making note of where the most valuable merchandise was. At nine o’clock, a half dozen friendly members of the city guard sent word that the coast was clear.

By ten o’clock, the men started out. They used a key to open a fancy dry goods store, swiping $15,000 worth of fine silks, muslins and other items. They pilfered silver watches and two to three gold timepieces, together worth $4,000 to $5,000. Some $3,000 worth of fine goods from a large clothing store disappeared into the burglars’ hands.

At half past eleven o’clock—with a change of the city guard a half hour away—the burglars packed their loot into butcher carts they had procured, setting fire to the looted stores. As they made their way toward the waterfront, the bandits hit every store they came to. Wind from the southeast spread the flames, and soon someone yelled, “Fire!” and an alarm bell sounded on Conception Street.

The men worked through the rest of the night loading a pair of boats while chaos gripped the city. Just before daylight, two fully packed vessels shoved off toward Dog River, some ten miles south of Mobile, arriving at about 8:00 a.m.

Tired but satisfied, the thieves held a meeting to report their haul: an estimated $25,000 worth, including an abundant supply of liquors and groceries. They divided the score, with the three leaders—Gale H. Wages, Charles McGrath and James Copeland—taking about $6,000 worth. They each selected the finest and most expensive items for themselves, packing jewelry, silks and other goods into trunks.

The Wages and Copeland Clan had struck again.

Meanwhile, Mobile was in flames. The fire had come just five days after another conflagration at a furniture store on Dauphin Street burned a city block.

Among other crimes, James Copeland confessed to starting one of the most devastating fires in Mobile’s history in 1839 as cover for looting stores throughout downtown. Doy Leale McCall Rare Book and Manuscript Library.

This one was far more devastating, and it hardly could have come at a worse time. The city was in the throes of one of its periodic yellow fever outbreaks, which meant that many able-bodied citizens were out of the city and many of the men who remained were sick.

The police and militia roused people from their homes so they could blow them up in a desperate attempt to create firebreaks to stop the flames from spreading.

Commission merchant Duke Goodman wrote to lawyer and politician James Dellet the next day that he had managed to save most of the furniture from his house, which had been destroyed.

The city awoke that day to find much of Dauphin Street, between Conception and Franklin Streets, in ashes. Some five hundred buildings had burned on several blocks to either side of Dauphin Street. Hundreds now were homeless. Investigators estimated the monetary loss at $2 million.

Sifting through fourteen demolished blocks, authorities fixed the blame on arson.

“Can it be possible there can be found in human shape, such base, fiendish monsters?” the Mobile Mercantile Advertiser asked its readers on October 9. “Mobile seems indeed a doomed city. Have we not drank [sic] deep enough of the bitter cup of adversity and affliction? When will our calamities end?”

It turns out, the calamities were not yet over. That very day, a third fire in seven days broke out, this time in an unoccupied room of the Mansion Hotel on the southeast corner of Conti and Royal Streets. The Planters and Merchants Bank and the nearly completed United States Hotel also burned.

A week later, Mobile still was a like a war zone, according to the Mobile Commercial Register.

“We walk among ruins, some of which threaten to topple down upon our heads,” the paper reported on October 18.

The origins of the October 1839 fires never have been definitively pinned down. Copeland, in a confession first published in 1858, mentioned setting fires to cover his gang’s looting. An 1843 newspaper article laid the blame on an escaped slave who supposedly had organized secret meetings with hundreds of other slaves. The conspirators, according to this account, mulled over the idea of murdering whites but then shifted to arson as part of a plot to gain freedom.

Layer after layer of legend and fact have piled on one another over the years to an extent that makes it impossible to separate the two when it comes to the Wages and Copeland Clan. The tales of depravity are so extensive and so voluminous that they seem impossible to represent the un-exaggerated truth—particularly considering the relative lack of attention the outlaws generated in the press during their own time.

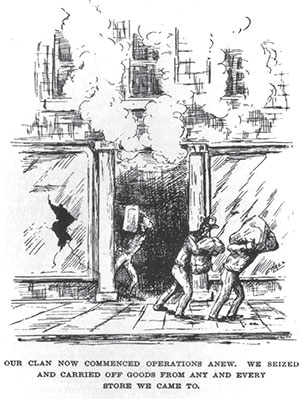

Many of the details of their mid-nineteenth-century crime spree come from Copeland’s own confession, given to the Mississippi sheriff who arrested him. Already a condemned man, Copeland at the time may have seen no downside to embellishing his own exploits.

What’s more, the lawman himself had incentive to exaggerate. He paid to have the long confession printed in pamphlet form and peddled it throughout the Southeast, battling allegations for libel from three of Mobile’s most prominent lawyers along the way.

Regardless of where the fact ended and the myth began, the Copeland name was enough to inspire shudders for decades along a wide swatch of the Coastal South. The name appears in many of the local county histories commissioned by the Works Progress Administration during the Great Depression in the 1930s.

A retired pension agent wrote a chapter on the gang in a book of his travels published in 1935. Parents in backwoods communities in Mississippi whispered the name of James Copeland to prod disobedient children to good behavior.

The story began on January 18, 1823, with the birth of a male child some ten miles from the Alabama line in the Pascagoula River Valley in rural Mississippi. That child was James Copeland, and his life of crime began twelve years later with the theft of a pocketknife from a neighbor.

Sent by his mother to Peter Helverson’s farm to get some vegetables, the young Copeland asked Mrs. Helverson if he could borrow the knife. She agreed but asked that he be careful with the tool, since it had been a present. James promptly hid the knife and then lied that he had lost it. He pretended to search, eventually leaving the disappointed woman behind.

“I was all the time laughing in my sleeve, to know how completely I had swindled her,” he later told the sheriff in his confession.

James claimed he bought the knife in Mobile. His mother, by his own account, upheld his “rascality.”

From there, he was off. He helped his brother, Isham “Whin” Copeland, steal a cartload of the Helversons’ finest pigs and haul them to Mobile, where they fetched two dollars a head. He swindled his classmates out of pocketknives and money. He would lie to get them flogged. All the while, his mother would run interference for him.

Copeland was still a boy when he faced his first serious legal trouble. Caught by Peter Helverson trying to steal from him again, Copeland found himself staring at criminal charges. That is when he met Wages, his future criminal partner. Wages, who was about six years older, discussed Copeland’s options—including the possibility of killing witnesses.

In the end, they settled on arson. Before Copeland’s trial arrived, the Jackson County Courthouse went up in flames. The conflagration destroyed the building, records and all.

Not long after that, Copeland formally joined Wages’s gang, taking an oath on a Bible in a wigwam near Mobile where the clan made its hideout: “You solemnly swear upon the Holy Evangelist of Almighty God, that you will never divulge, and always conceal and never reveal any of the signs or passwords of our order; that you will not invent any sign, token or device by which the secret mysteries of our order may be made known; that you will not in any way betray or cause to be betrayed any member of this order the whole under pain of having your head severed from your body—so help you God.”

He pledged to keep the clan’s secrets and accepted signs and passwords. He learned the secret alphabet invented by John Murrell, a notorious outlaw from Tennessee, from which Wages supposedly had broken.

“We ranged that season from one place to the other, and sometimes in town, stealing any and everything we could,” he said during his confession.

The plunder included beef, hogs, sheep and sometimes a fine horse or mule—“and occasionally a negro would disappear.”

Back at the gang’s hideout on October 8, 1839, Copeland, McGrath and Wages took three separate routes to Apalachicola, Florida. They sold most of their loot in a wealthy neighborhood near the Chattahoochee River. An older woman bought jewelry from Copeland, who feigned illness and wrangled an invitation to stay in her home.

Copeland sweet-talked the woman’s seventeen-year-old slave girl and made arrangements for her to sneak away with him to be his wife. He told her that he would carry her to a free state.

The girl met Copeland, and the two stole a canoe and rowed for three days to Apalachicola. He stashed the girl, along with a slave that McGrath had kidnapped, in a swamp five miles from town. That night, Copeland and McGrath met some Spaniards at a coffeehouse and learned they had a schooner that they were going to sail to New Orleans.

The men made arrangements to smuggle their girls—along with a third escaped slave, taken by Wages—onto the vessel. The next night, they arrived at the Pontchartrain Railroad and headed into New Orleans. They ate breakfast at nine o’clock in the morning and then left on the Bayou Sara steamboat, eventually selling the slaves to a rich planter along the Mississippi River.

The seventeen-year-old girl who thought she was on her way to a new life in a free state with a charming husband fetched Copeland $1,000.

“My girl made a considerable fuss when I was about to leave, but I told her I would return in a month, and rather pacified her,” he later told the sheriff. “I must here acknowledge that my conscience did that time feel mortified, after the girl had come with me, and I had lived with her as a wife, and she had such implicit confidence in me.”

The three outlaws took their money and left for Mobile, stopping for a few days in New Orleans to rob a store. They landed in Pascagoula, Mississippi, and walked the remainder of the journey to Mobile. Each man had $4,500, which they hid in the ground, taking only $150 for expenses.

It was the beginning of a crime spree that would last more than a decade.

Wages, Copeland and McGrath set off for Texas in March 1841. Traveling up the Mississippi River, Copeland and Wages taught McGrath how to pray, sing and “give that long Methodist groan.”

Within a few days, McGrath got a chance to try out his new Protestant act. At a Methodist Church in Natchitoches, Louisiana, he posed as Reverend McGrath from Charleston, South Carolina. He preached and then led the congregation in reciting an old hymn.

“Wages sang bass and I tenor, and we made that old church sound like distant thunder,” Copeland later recalled.

McGrath preached some more, read Bible verses and sang another hymn. He left the church with some of his newfound brethren while Copeland and Wages found a gambling den.

The next day, McGrath returned to the church and told the congregation that he was poor. The parishioners took up a collection and gave him a fine black suit, a new saddle and saddlebags and fifty dollars cash. It was a ploy McGrath would repeat many times—preaching from the good book while his confederates stole horses from unsuspecting congregants.

Meeting outside Natchitoches, McGrath, Wages and Copeland made their next plan: McGrath was to rendezvous with the other two men on September 1 in San Antonio, Texas.

Wages and Copeland continued to a plantation, where they mixed poison and whiskey and killed the overseer. They stole ten slaves and two fine horses. Near San Antonio, they got $1,600 for the slaves.

The pair spent some time at a Mexican ranch in Texas, eventually luring a pair of ranch hands on the proposition of buying thirty horses and thirty mules. Executing a plan drawn up by Wages, Copeland pointed a gun at the sleeping younger man’s head and waited for his friend and mentor to fire his weapon at the other man.

Wages fired, and Copeland almost simultaneously pulled his trigger. Both victims gave a suppressed, struggling scream and then died. Wages and Copeland spent the next day covering up their murders. They tied the bodies to a pole and then carried them to a sinkhole near camp, burying them along with their bloody clothes and hatchets. They then built fires on the camp where the bodies had been.

Then Wages and Copeland drove the herd to Wilkinson County, Mississippi, where they got $50 for each of the mules and an average of $75 for each of the horses. They sold them all except for four saddle horses. Two of those animals eventually fetched $100 each. Wages later got $150 for the horse belonging to one of the Mexicans and $25 for the one that Copeland had been riding.

The trip had netted $6,675. Wages and Copeland deposited the money in a New Orleans bank and spent the Fourth of July in the city.

The partners then took a steamship to Shreveport, Louisiana, and traveled by wagon to Texas. Along the way, they saw a slave driving horses. He told the men that his master beat him and did not feed him enough. Wages told the man he would take him to a free state. The slave stole three horses at Wages’s request and joined him and Copeland.

They ran into John Harden, who had been stealing slaves in Tennessee. He told the slave who Wages had lured that he was an agent for an abolition society in Cincinnati. The slave followed Harden, traveling under the name John Newton, who promptly sold him along the Arkansas River for $1,250.

In February 1842, having reunited with McGrath, the bandits took a steamboat to Pittsburgh, landing on the Wabash River. They met an Irishman named O’Connor, a western trader with two large flatboats, and hired him.

Wages prepared a strong whiskey punch and left it to Copeland to deliver the fatal blow. He crept into O’Connor’s cabin at sunrise and swung a lathing axe in the center of the sleeping man’s forehead, a little above his eyes. The victim uttered a kind of suppressed shriek and was dead within minutes.

The three men went quickly to work, stripping the man’s clothing and then tying a rope around the naked man’s neck, tossing the cadaver overboard attached to heavy, cast-iron grates to weigh the body down.

“Oh God! When I look, it makes me shudder,” Copeland would later say. “Even now it chills the blood in my veins.”

They rubbed off the names of the vessels, Non Such and Red Rover, replacing them with the monikers Tip and Tyler. The boats, with cargo worth more than $5,000, glided down river. A man named Welter paid the men $4,500 and sent one of the boats down the Atchafalaya Bayou in south-central Louisiana and the other to his home along the Mississippi River.

Wages, meanwhile, returned from New Orleans with five barrels of whiskey and a load of gold coins. He placed the coins into three strong kegs made in Mobile so that each contained $10,000 worth. Wages, Copeland and McGrath covered the coins in clean, white sand and applied three coats of fresh paint to the containers. After the paint dried, the trio buried the kegs in a thick swamp along Hamilton’s Creek near Mobile.

The men kept the remainder of the booty in cash, $625 each.

Upon returning to the wigwam, Copeland and Wages discovered that the clan had elected a new president. Reasserting control after a two-year absence, Wages announced that the organization’s Vigilant Committee would make a report. Before that date arrived, he and Copeland formed a new group with a small number of men, including Copeland’s brothers: Whin, Henry, John and Thomas. The new group then disposed of four “spies and traitors” from the original group; their bodies floated from the Mobile wharf down the river channel.

Two years later, in 1846, Wages married and built a house in Hancock County, Mississippi. He dug up the kegs of gold and reburied them in Catahoula Swamp about two miles from the homestead. He marked the new hiding place by a large pine tree and gave Copland a diagram to its location.

The following year, Copeland, his brother John, Allen Brown and McGrath hatched a plan to rob the house of a ferry operator named Eli Moffett, who had a contract to construct a bridge in Perry County, Mississippi. They decided to strike while Moffett was away from his home in the northern Mobile County community of Wilmer and planned to leave his family unharmed.

“That, I opposed, for I never believed in leaving any witnesses behind to tell what I had done,” Copeland told Perry County sheriff James Robinson Soda Pitts during an extended confession.

The bandits stormed the house just after dark on December 15, 1847. When Moffett’s wife, Matilda, refused to cooperate, John Copeland struck her head, and James Copeland delivered several blows of his own. They ransacked the home but found only a small amount of money before setting the house on fire.

James Copeland gave an extended confession to Perry County (Mississippi) sheriff James Robinson Soda Pitts just before his execution in October 1857. Doy Leale McCall Rare Book and Manuscript Library.

They thought Matilda Moffett was dead, but she managed to survive the beating and fire.

The stage for the downfall of the Wages and Copeland Clan was set by a decision that Copeland fought—to enter the counterfeiting business. He believed it unwise but reluctantly agreed to join his compatriots.

Allen Brown got himself arrested on counterfeiting charges. Later, Wages and McGrath got into a heated argument with a regulator named James A. Harvey over a forty-dollar note. Brown had sold a farm to Harvey. When Harvey discovered that Brown did not have proper title to the property, he refused to pay. He ended up shooting and killing both Wages and McGrath.

Responding to a $1,000 reward offer from Wages’s parents, James Copeland put together a revenge party armed with double-barrel shotguns, pistols and bowie knives. The men set off for Perry County, Mississippi, on July 8, 1848. They arrived the following Saturday in what is present-day Forrest County to find the Harvey home empty.

The men entered the house and made portholes on every side so they could fire upon Harvey as he approached. They took turns, in two- and three-hour shifts, watching for the homeowner’s return. It was a monotonous affair. Copeland and his men ate figs, peaches and watermelon, destroying more than they consumed.

In the afternoon, hunger set in, and Copeland proposed going to Daniel Brown’s house to get some meat and bread. But the others objected to the mile walk. Instead, Sam Stoughton gathered twenty ears of corn while Jackson Pool got a load of wood to make a fire.

“That is precisely what betrayed us—the smoke issuing from the chimney house,” Copeland later recalled.

As night fell, John Copeland took his turn on watch. Stoughton, Pool and Copeland sat on the veranda, talking in muted voices. They saw a large, white fowl run through the yard, fifteen or twenty yards from them.

Pool took it as a warning.

“Boys, I shall be a dead man before tomorrow night!” he said. “That is an omen of my death!”

Stoughton laughed, telling him that if he were a dead man, he was quite a noisy corpse.

“I did wrong in making fire in the house,” Pool insisted.

All of the men had difficulty sleeping. They discussed giving up but decided to wait to see if Harvey returned after breakfast. Between eight and nine o’clock the next morning, while the Copland gang was eating figs and peaches, John Copeland called out, “Boys, here comes a young army of Black Creek men!”

The men ran into the house. Pool grabbed his gun.

“Boys, take your guns,” he yelled.

The approaching men separated, and someone said, “Come on, boys, here they are!”

Copeland ducked out of the house at first opportunity, darted around a large fig tree and gazed back at the house. Pool was standing in the door. Harvey came around the corner of the house to Pool’s right and jumped into the veranda. Pool shot, striking Harvey’s left side. Harvey returned fire, hitting Pool in the side.

Pool staggered into the yard, and another man shot him in the chest.

Stoughton and John Copeland jumped out of the door and ran. James Copeland turned as the crowd ran around the house. A gunshot whistled past Copeland’s head. Hearing a barrage of gunfire, he ran so hard that, to him, he seemed to be flying above the ground. When he felt he no longer was in danger, he stopped and reflected on his life, vowing to become a Christian and renounce his criminal ways.

It was not until he was away from the gun battle that he realized he had lost the diagram to the treasure Wages had buried in the Catahoula Swamp.

Copeland later came across his brother, who was hiding in waist-deep mud, and learned that Stoughton also had made it out. Wages’s father happily paid the second half of the reward, in part with livestock.

Harvey, meanwhile, lingered for ten days before succumbing to his mortal wounds on July 25.

Stoughton later got arrested trying to sell his reward oxen. He died in prison.

Copeland took to drinking.

In the spring of 1849, he found himself with three of his brothers at a grocery store near Dog River, about twelve miles from Mobile. Drunk and paranoid, Copeland tried to kill a man named Smith, who stabbed him in the collarbone in self-defense.

Copeland staggered out of the store and ran about two hundred yards before collapsing. His brothers carried him two miles. An arrest party, following the blood trail, came and took him into custody. He pleaded guilty to larceny in order to avoid a murder charge and served four years of hard labor in Wetumpka, Alabama.

The end of Copeland’s sentence, though, was only the beginning of his legal problems. He would never see freedom again.

J.R.S. Pitts, the Perry County sheriff, was waiting to extradite Copeland back to Mississippi to stand trial for the murder of Harvey. The trial opened on September 16, 1857, and the jury convicted him a day later. Judge W.E. Hancock pronounced the death sentence on September 18.

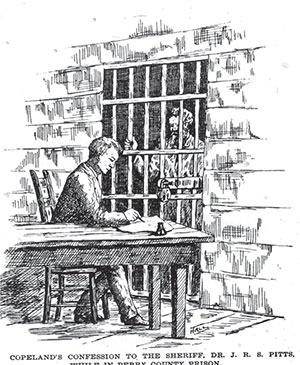

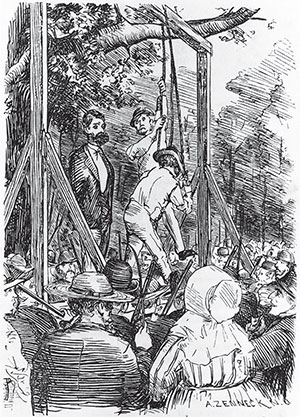

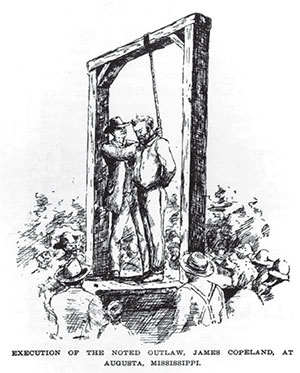

James Copeland was hanged on October 30, 1857, for the murder of James A. Harvey. Doy Leale McCall Rare Book and Manuscript Library.

The date of the execution, October 30, 1857, was a clear and beautiful day, with a bright blue sky. On the banks of the Leaf River, about a quarter mile from the county seat of Augusta, Mississippi, Copeland was hanged for his crime. As Sheriff Pitts put it, Copeland “expiated his bloodstained career on the scaffold.”

The night before his execution, Copeland penned a letter blaming his mother’s indulgence. “You are knowing to my being [sic] a bad man and dear mother, had you given me the proper advice when young, I would now perhaps be doing well,” he wrote.

Decades after Copeland’s execution, the legend of the Copeland and Wages Clan has both grown and come under scrutiny. Treasure hunters for years have searched in vain for the buried gold. A Perry County man is said to have found the secret map but could not understand its markings. He showed it to people in Mobile; a prominent citizen supposedly asked to look at the document and then ran off with it.

According to legend, a black man named Wash Denton later dug up Copeland’s body and carried it by horse to the home of J.B. Kennedy, who cut off the flesh and soaked the bones in vinegar. After they dried, Kennedy put the skeleton together with wire and buried the flesh at the old Denton place.

The skeleton ended up on display at a drugstore in Moss Point, Mississippi, along the Gulf coast. Another version of this tale names the establishment as McInnis and Dozier Drugstore in Hattiesburg. But at any rate, it has not been seen since the early 1900s.

Copeland’s arrest on the larceny charge in 1849 brought one short mention in the Alabama Planter newspaper on April 1: “James Copeland, one of the gang of ruffians who have so long infested this country, was yesterday brought to the city, by a person named Smith.”

Would a band whose exploits were as widespread and dastardly as legend later declared not have attracted more attention? As historian James Penick put it: “In 1849, Mobile seemed blithely unaware that a ten-year reign of terror had come to an end.”

October 30, 1857, was a clear, beautiful day with a bright, cloudless sky as executioners led James Copeland to the gallows erected about a quarter mile from the banks of the Leaf River. Doy Leale McCall Rare Book and Manuscript Library.

Another historian expressed skepticism based on the language of the confession, itself. Were those really the articulate words of a backwoods thief with little formal education? Or did the sheriff, Pitts, embellish?

Pitts had motive to conjure the most riveting account possible. He had the confession printed in Mobile and worked hard to sell it. His efforts landed him in jail for a time, charged with libeling three prominent lawyers named by Copeland as members of his gang—Gibson Y. Overall, George A. Cleveland and Cleveland F. Moulton.

George Cleveland, Copeland told Pitts in his confession, “traveled then in considerable style, with two large leather trunks, and they were mostly packed with this spurious money.”

A grand jury indicted Pitts in October 1858, and he went on trial in the Overall case in February 1859. Overall was able to show that he was a schoolboy in Columbus, Mississippi, during the relevant period. Pitts was convicted and sentenced to three months in jail. The other two cases were postponed for two decades, but Pitts had to return to Mobile once a year—even while he was serving in the Confederate army during the Civil War—or forfeit his bond.

There might not have been proof that Cleveland and Moulton were part of Copeland’s gang, but there is a fair amount of historical evidence that they were not exactly clean, either. George Cleveland was indicted on an extortion charge in February 1859, the same month of Pitts’s libel trial. He also faced charges of gambling and of using his office as justice of the peace to enrich himself.

Cleveland and his nephew, Moulton, were indicted on a charge of “assault to murder.” They beat that charge, but a jury convicted Moulton of a lesser assault and battery charge; he paid a $1,000 fine. And he was indicted on an embezzlement charge.

Augustus Brooks, who often posted bond for Cleveland and Moulton, was fined for selling Negroes without a license.

Even the tale of Copeland’s entry into the clan—the supposed arson of the Jackson County courthouse—has been called into question. Courthouse fires in those days were, in fact, fairly common occurrences. Half of Mississippi’s eighty-two courthouses have burned, some more than once. And would a fire, even one that destroyed court records, really have stopped Copeland’s prosecution? The farmer Helverson could have made a new complaint, and a grand jury could have re-indicted the defendant.

After his three-month stint in jail, Pitts went on to medical school in Mobile. He enjoyed a distinguished career as a physician, a county superintendent, a state legislator, a presidential elector and a postmaster in Waynesboro, Mississippi. But his name never reached the prominence of James Copeland—the myth he largely created.