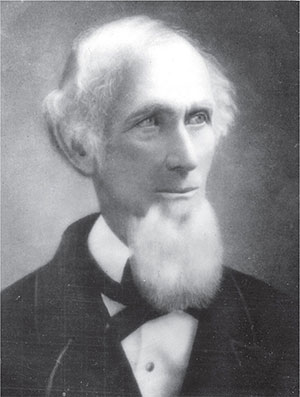

Dr. Josiah Nott was an enigma—ahead of his time in matters of medicine and science but a retrograde racist, even by the standards of his own time. Doy Leale McCall Rare Book and Manuscript Library.

Chapter 5

THE ENIGMA OF JOSIAH NOTT

In the middle part of the nineteenth century, Mobile had a true visionary, a man who possessed formal training and a curious, scientific mind that resulted in new and modified surgical instruments. His work on the longtime scourge of the South, yellow fever, planted the early seeds that one day would lead to its eradication in the United States. “The Barbific cause of Yellow Fever is not amendable to any of the laws of gases, vapor, emanations, etc., but has inherent power of propagation, independent of the motions of the atmosphere, and which accords in many respects with the peculiar habits and instincts of Insects,” he wrote, rejecting commonly held beliefs of his day.

And nineteenth-century Mobile was home to a physician of the first order, a classically educated doctor who brought the profession’s best attributes to bear. He was mindful of the Hippocratic oath—“Do no harm”—in treating a vast cross-section of Mobile, from the city’s elite to its slaves: “I can honestly say, gentlemen, and it is the proudest boast of my life, that for the first ten years of my professional career, I never refused to see a human being, night or day, far or near, or in any weather, because he could not pay me.”

The same period also produced one of the most viscous racists Alabama had ever seen, a man whose pedigree and status not only made him an important voice in the South but also gave him credibility in the North, as well. “Slavery is the normal condition of the Negro, the most advantageous to him, and the most ruinous, in the end, to a white nation,” he wrote.

Meet Dr. Josiah C. Nott, Josiah C. Nott and Josiah C. Nott.

Dr. Josiah Nott was an enigma—ahead of his time in matters of medicine and science but a retrograde racist, even by the standards of his own time. Doy Leale McCall Rare Book and Manuscript Library.

Nott was all of those things, an enigma whose seemingly contradictory views owed as much to his times as to the particulars of his upbringing.

He traced his roots to the early colonial period. John Nott came to Connecticut in 1604. His grandson, Abraham, became a Congregational Church minister. Abraham’s grandson, also named Abraham, headed south after graduating from Yale University in 1787, eventually settling in South Carolina, where he ran a successful law practice. He went on to become a judge, serving as president of the South Carolina Court of Appeals in 1824.

It was here that Josiah Clark Nott came into the world on March 31, 1804. Despite his family’s New England roots, Nott was thoroughly southern. He attended Columbia Male Academy and then South Carolina College.

The college’s president Thomas Cooper espoused a vigorous defense of the South’s institution of slavery, states’ rights and the rejection of the Bible as the source of scientific truth. All of those ideas had a great impact on young Nott, and he would carry them throughout his long and prolific career.

The events of the day also made their mark on Nott during his formative years, particularly a slave uprising led by Denmark Vesey in 1822. The plotted revolt shocked South Carolina’s white population; more than thirty people hanged, and another thirty were banished.

When Nott graduated in 1824, he became one of five male members of his large family to pursue a career in medicine. He began a medical apprenticeship in Columbia, South Carolina, and then attended the College of Physicians and Surgeons in New York City. Amid internal strife at the school, Nott transferred to the prestigious University of Pennsylvania, where he completed his studies and paid forty dollars for his degree in March 1826.

Returning to the South Carolina capital in 1829 to start his own medical practice, Nott three years later married Sarah “Sally” Deas, the daughter of a prominent South Carolina family whose patriarch served eight years in the state legislature and was a high-profile supporter of the nullification movement.

Nott furthered his medical training in 1835 with a year of studies in Paris, at the time the mecca of advanced medicine.

Medicine of the early nineteenth century had not yet undergone the revolution of knowledge that would transform the profession. There still was much about the workings of the human body and disease that doctors did not know. But by the time Nott packed up his family and headed to Mobile in May 1836, following in his father-in-law’s footsteps, he already was one of the best-educated, best-trained doctors in America.

Nott was hardly alone in his move west. Mobile in the 1830s was a boomtown, fueled by the incredible profitability of the cotton trade. Although Mobile County was not a major player in the crop’s harvesting, as the only port in the state, a large share of the cotton that Alabama exported went through the city.

It made many families rich and attracted adventure-seekers from across the South. Its population nearly quadrupled from 1830 to 1840, rising from about 3,200 to 12,600.

Nott opened his medical practice near the customhouse on Royal Street and quickly gained a following.

“Mobile is essentially a money making place,” Nott wrote to a former student in 1836. He estimated that he would earn $8,000 to $10,000 in the coming year.

In a February 1837 letter to a friend, he wrote, “I have made a very fair start in the professional way and shall do well I think.”

Nott’s high opinion of himself was matched by his contempt for most of the established physicians in town. To the former student, he wrote in June 1839 that the doctors were “making a mockery of fortunes by the intrepidity of ignorance.”

By and large, life was good. His wife joined Christ Episcopal Church. He helped found the Mobile Medical Society to improve the professionalism of his chosen field, and he served on a three-man committee to draft a code of laws for the organization.

By 1840, he owned nine slaves; that number would grow to sixteen by 1850, and his real estate holdings totaled $15,000. That placed him just a notch below the city’s wealthy elite—a group of only about twenty-five men, mostly merchants, who had real estate valued at more than $30,000 at the time.

As his practice continued to grow through the decade, he opened an infirmary for blacks, free and slave, on Royal Street near the slave market.

With his private practice booming, Nott turned his attention to the area of medical knowledge. Over the course of several decades, he was a prolific writer, contributing to medical journals. In 1838, for instance, he published in the American Journal of the Medical Sciences his suggestion for improving the design of a jointed splint for leg fractures. He wrote that he has used the device to successfully treat three or four patients, including a slave who had fallen through the trapdoor of a warehouse and suffered a double fracture.

By the 1840s, Nott’s medical acumen had begun to generate attention outside Mobile. He invented a number of surgical procedures and improved others. He exhibited calm during crises.

He drew an admiring account by biographer Arthur William Anderson, who wrote in 1877 that Nott “performed so well, with dexterity, boldness, and astonishing self-reliance.”

Nott tended to keep his extreme race views out of his medical observations and demonstrated a willingness to take risks for the cause of scientific knowledge. He began experimenting with hypnosis as a method of treating “nervous conditions.” He wrote of success treating one woman’s acute pain from an infected molar. In another case, he removed two bones to treat a tailbone condition that would come to be known as coccygodynia.

He gave a talk to the Franklin Society of Mobile in 1846—for twenty-five cents a head—on “The Phenomena of Mesmerism,” or animal magnetism, despite ridicule from the medical community.

The reviews of Nott’s work, however, mostly were exceedingly positive, both among contemporaries and those who wrote decades after his death. In the Medical History of Mobile, in 1847, for example, Dr. Paul H. Lewis gushed that Nott was “one of the most competent and careful pathologists in the South.”

Nine years later, the New Orleans Medical News and Hospital Gazette wrote: “Southern surgery has not been awarded the position to which it is entitled, and it is simply because our surgeons are too sparing of their ink; we know of no one better calculated to place us aright than Dr. Nott, and we are sure that his silence is not because he loves surgery less, but that he loves other subjects more.”

Dr. William Augustus Evans, who became Chicago’s first public health commissioner in 1907, praised Nott’s legacy decades after his death: “Dr. Nott deserves that his name shall live.”

Willis Brewer, in his history of Alabama, wrote: “As a man he is highly esteemed by those who know him best, for he unites the sentiments and manners of a Southern gentleman with the acquirements of a savant.”

Nott’s sterling reputation was not without merit. In matters of medicine, he was an innovator. In 1855, he published an article in the New Orleans Medical Journal about a tool he had invented to remove infected tonsils. A year later, he published a medical journal article about using wire splints instead of thin patchboard to heel broken bones.

He offered practical advice to surgeons for treating gunshot and other bone injuries and how to respond to problems after the initial surgery. Other areas receiving attention from Nott included treatment of necrosis, or dead bone, and chronic osteitis, or inflammation.

Throughout his career, Nott expressed skepticism for “heroic treatment,” preferring to let the body heal itself whenever possible. He wrote, for example, that doctors should allow nature to heal splinters still partly attached to muscles and tendons.

Toward the end of his career, after developing a specialty in gynecology, he sought a middle ground on uterine surgery, writing that the uterus had been cut too much and burnt too much.

He developed a method to stop hemorrhaging of the cervix after operation and came up with a modified speculum for uterine exams and that he claimed was easier to carry for house-to-house visits. He also commissioned a New York instrument manufacturer to build a uterine catheter of his own design.

Well into his sixties, as a relatively new resident of New York City and without a great deal of experience in his newly chosen specialty, Nott became president of the New York Obstetrics Society.

Again and again, Nott put people’s medical needs above his personal biases. He treated hated Union troops stricken with yellow fever and drew praise for his work responding to a munitions depot explosion that destroyed several city blocks in Mobile and killed two hundred people just after the end of the Civil War.

On no medical topic did Nott gain greater attention, though, than the scourge of the southern states since Europeans first landed in the New World: yellow fever. It was a horrible disease, marked by headaches, chills, back pain and rapid rise in body temperature. Vomiting and constipation followed and then, days later, organ collapse. The vomit turned yellow and then mixed with black fluids.

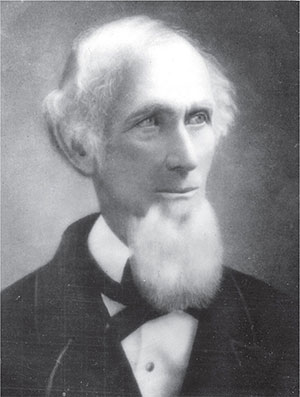

Dr. Josiah Nott (not pictured) was one of the founding members of the Can’t-Get-Away Club, which helped care for the sick and others left behind during yellow fever outbreaks in Mobile. Doy Leale McCall Rare Book and Manuscript Library.

The disease was as perplexing as it was panic inspiring. It would tear through cities with a vengeance some seasons and be completely absent in others. Its patterns had no apparent rhyme or reason. The only defense was to abandon the city at the first sign of an epidemic. Residents who could afford to would flee to safer ground and stay away until medical authorities declared the epidemic over after the first frost.

Those who could not escape would hunker down in their homes. Nott always remained to care for the mass numbers of sick. He was a founding member of the Can’t-Get-Away Club, a nineteenth-century Mobile organization that catered to the ill and others who remained trapped in the city.

Nott paid a heavy personal price. In September 1853, he watched four of his children die in succession from the disease. His brother-in-law James Deas also perished. Yellow fever claimed his nephew Charles Auzé in November of that year. Even in an era when the death of children was commonplace, it was an unusual toll for one family to bear.

Nott made important advances both in the treatment of yellow fever and its possible causes. Benjamin Rush, one of the founding fathers and America’s most famous early physician, counseled a harsh regimen of treatment: three doses of mercurous chloride, an herbal purge every six hours and bloodletting. He also recommended cooling the patient and administering quinine, a white crystalline alkaloid used to treat malaria.

Nott, however, rejected that course of treatment. In 1843, he found success stopping vomiting with creosote, alcohol and a solution of ammonium acetate with a glass of water every two hours. In 1845, he published “On the Pathology of Yellow Fever” based on his observations of five epidemics that had struck Mobile during his career and sixteen autopsies performed by himself and others. He correctly figured that the hallmark black vomit was the result of blood mixing with stomach acid. He concluded that the disease was a “depressing morbid poison” that people received through the atmosphere but was not spread person to person.

“Beware of the Lancet,” he cautioned in treating patients. “I would lay down a general rule that this is not a disease which demands active depletion, either by blood letting or purging.”

In DeBow’s Review in 1855, he wrote: “More good is effected by good nursing and constant attention to varying symptoms than by violent remedies.”

In an 1848 paper, Nott also challenged the theory popularized by Rush and others that “miasmas” caused by decaying vegetable and animal matter caused the disease or that unclean air played a role. Nott instead pointed to “reasons for supposing its specific cause to exist in some form of Insect Life.”

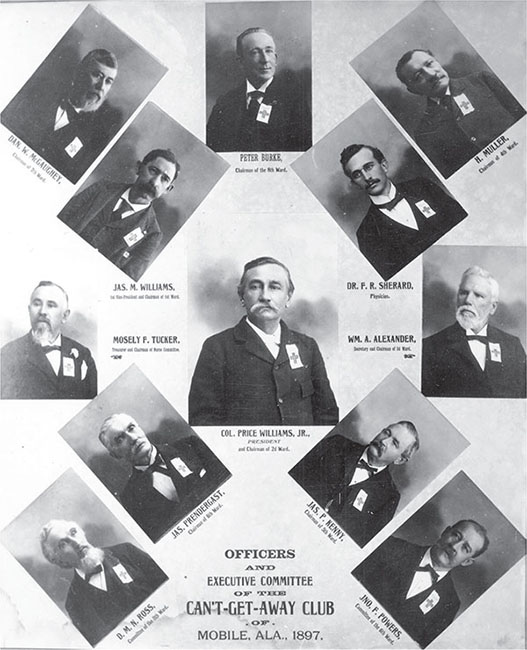

Dr. Josiah Nott was one of the most successful physicians in Mobile and known throughout the nation for his theories on racial origins. Doy Leale McCall Rare Book and Manuscript Library.

He wrote of a “perfect analogy between the habits of certain insects and Yellow Fever” and compared it to cotton pests. He observed that weather patterns had no effect on the spread of the disease except that very heavy rains seemed to impede marsh insects and that frost killed them.

“Chaillé, I’m damned if I don’t believe it’s bugs,” he said to a New Orleans colleague during an autopsy. Nott speculated that science one day would be able to identify “animalcules,” using the Latin term for microscopic organisms that caused the disease. He wrote that there was “every reason to believe that countless species still exist, too small to be reached by our most powerful microscopes.”

In another paper, he wrote: “Even animalculae, so infinitely small to our senses, many in turn become gigantic, compared to others yet to be discovered with more perfect instruments.”

Nott clearly was on the right track and often has been credited as an early forerunner of the men who eventually would unlock the secrets to eradicating the deadly disease from North America. One of those men was William Crawford Gorgas, whom Nott delivered in 1854. He was part of the yellow fever commission in Cuba that proved that mosquitos transmitted the disease and ordered the draining of ponds and swamps, along with other protocols for halting the disease.

Some modern historians argue that Nott gets more credit than he actually deserves. Despite his references to insects, they contend, he was far from making the crucial link between yellow fever and mosquitos. Harvard University professor Eli Chernin in 1983 wrote that Nott’s views were “often vague, muddied or inconclusive.”

Still, without the benefit of a more advanced understanding of the nature of germs that medical science simply had not yet uncovered, Nott discounted the dominant thinking that actually made yellow fever worse for its patients.

As careful and open to new evidence as Nott was in matters regarding medicine, he exhibited a reflexivity toward race that was a hallmark of the nineteenth-century slave owner.

Although Nott treated black patients throughout his career, his writings reveal the cold and clinical way in which he viewed them. He warned in 1847 that it would be unsafe for insurance companies to write polices on human property on the plantations in the country. He feared that many fraudulent policies would be purchased for “unsound” slaves.

“As long as the negro is sound, and worth more than the amount insured, self-interest will prompt the owner to preserve the life of the slave; but if the slave become unsound and there is little prospect of perfect recovery, the underwriters cannot expect fair play—the insurance money is worth more than the slave, and the latter is regarded in the light of a superannuated horse.”

And then? “That ‘Almighty Dollar’ would soon silence the soft, small voice of humanity,” he wrote.

Nott’s career as a physician firmly established in the 1840s, he began writing on ethnology, the study of racial and cultural differences. It was here that Nott achieved his widest level of acclaim. His many books, pamphlets and journal articles on the subject all revolved around the central premise of the inferiority of blacks—and, indeed, all other nonwhite races.

He dismissed any evidence of great, nonwhite civilizations. The ancient ruins of the Central American Indians proved nothing other than a talent for architecture. But Nott argued in a lecture delivered at Louisiana State University that too much emphasis has been placed on those architectural accomplishments, which he compared to the talents of beavers in constructing dams or bees of making hives.

Nott found those ancient societies wanting in the areas of art, culture, government and laws.

“Everything proves that they were miserable imbeciles, very far below the Chinese of the present day in every particular,” he said.

White superiority was hardly a controversial idea in nineteenth-century America, particularly in the South. But Nott raised the argument to a new level, arguing that Negroes were not merely inferior to whites but, in fact, a separate and distinct species altogether.

While Nott’s racist ravings had few dissenters in the Mobile of his time, the same was not true for religious heresy. His theory that blacks and whites were separate species required a rejection of the orthodox belief in God’s creation of the human race in the Garden of Eden. Nott chose to confront this contradiction with a full-bore attack on the Bible.

“How could the author of Genesis know anything of the true history of the creation, or of the races of men, when his knowledge of the physical world was so extremely limited?” he asked in a lecture delivered at Louisiana State University in 1848.

Nott expanded on that in an appendix he wrote for The Moral and Intellectual Diversity of Races in 1856.

“The Bible should not be regarded as a text-book of natural history. On the contrary, it must be admitted that none of the writers of the Old or New Testament give the slightest evidence of knowledge in any department of science beyond that of their profane contemporaries.”

Nott wrote of the different characteristics of various species of felines, elephants, bears and other animals. When white Europeans are placed alongside black Africans, he wrote, “they are marked by stronger differences than are the species of the genera above named.”

Nott’s forceful and highly public argument drew fierce reaction from church leaders who could not reconcile the doctor’s views of multiple creations with the supposedly infallible Bible. Nott had harbored antireligious views at least as early as his college days, when he watched his mentor, Thomas Cooper, take heat for similar ideas. As his stature grew, he accepted—and at time appeared even to relish—conflict with the church.

Nott presented the veneer of scientific inquiry on matters of race, and his credentials lent his writings a cache that other defenders of slavery lacked. But his writings on ethnology lacked the careful attention to the scientific method of his published work on medicine. In “The Mulatto Hybrid” in the American Journal of Medical Sciences in 1843, for instance, Nott asserted—with scant evidence—that mixed-race people were less fertile than either whites or blacks.

He based his assertion on fifteen years of observation during his medical practice. Mulattoes, he wrote, were less capable of endurance, shorter-lived, more susceptible to female diseases and “bad breeders” more prone to miscarriages. Nott offered no statistics, though, and casually acknowledged that there were exceptions to the “truths” he had laid out.

The evidence Nott used to support his ethnological writings was comical at times. He wrote in The Moral and Intellectual Diversity of the Races that he had contacted three Mobile hat dealers and a New Jersey manufacturer to determine the brain sizes of various races.

At other times, he offered no evidence at all. He asserted that the Negro brain was smaller, with larger nerves and a different-shaped head, all of which proved that “the intellectual powers [were] comparatively defective.”

He contrasted the white woman, “with her rose and lily skin, Venus form and well chiseled features” with “the African wench, with her black and odorous skin, woolly head and animal features.”

The differences between the two were as great as that of a swan and a goose, or a horse and an ass, he wrote.

Nott attained his greatest fame with the 1854 publication of Types of Mankind, a bestseller that printed its tenth edition in 1871. Filled with crude racial stereotypes, the book expanded Nott and coauthor George Gliddon’s ideas of multiple creations. At the top of the hierarchy was unquestionably the white man, specifically the white man of northern European descent. Nott considered Germans to be the “parent stock” of the highest modern civilization.

“Nations and races, like individuals, have each an especial destiny: some are born to rule, and others are to be ruled,” Nott wrote in his portion of the book. “And such has ever been the history of mankind. No two distinctly-marked [sic] races can dwell together on equal terms. Some races, moreover, appear destined to live and prosper for a time, until the destroying race comes, which is to exterminate and supplant them.”

Nott maintained that the characteristics of the separate races had not changed in thousands of years, observable from the writings and drawings of ancient Egyptians, no matter what climate members of those races lived in.

“Numerous attempts have been made to establish the intellectual equality of the dark races with the white; and the history of the past has been ransacked for examples; but they are nowhere to be found. Can any one call [sic] the name of a full-blooded Negro who has ever written a page worthy of being remembered?”

It flowed naturally from such thinking that the enslavement of an entire race of people was justified; in fact, it was beneficial to the enslaved.

“Slavery is the normal condition of the Negro, the most advantageous to him, and the most ruinous, in the end, to a white nation,” Nott wrote.

Blacks could achieve in certain areas, under certain limitation, Nott wrote elsewhere in the book. “Every Negro is gifted with an ear for music; some are excellent musicians; all imitate well in most things; but with every opportunity for culture, our Southern Negroes remain as incapable, in drawing, as the lowest quadrumana.”

It was an argument Nott had made before. In his Two Lectures on the Connection Between the Biblical and Physical History of Man, Nott had argued that black Africans could make modest improvements under the care of white men but that those improvements maxed out after the second generation.

“Their highest civilization is attained in the state of slavery, and when left to themselves, after a certain advance, as in St. Domingo, a retrograde movement is inevitable.”

It is but one of many, many writings in which Nott sought to justify slavery.

He did more than write to defend the institution. He acted, as well. In August 1856, he served on a “vigilance committee” that condemned a pair of booksellers, William Strickland and Edwin Upson, for selling “incendiary” titles like Uncle Tom’s Cabin and the works of black freedom fighter Frederick Douglass. Citizens painted over signs, and the committee delivered an ultimatum for the businessmen to leave the city within five days.

Upson later recalled that Nott and two other physicians confronted him in a room at the Battle House Hotel. Dr. J.H. Woodcock had a carriage and rope and was prepared to hang him, according to Upson’s account.

Strickland returned to Mobile in January 1858 to try to collect $25,000 in debts owed to his business. Instead, he was confronted by a $250 reward for anyone who would point out the “lurking place of William Strickland.”

“It is the misfortune of Mobile that she has borne in her bosom a set of bad, reckless, unprincipled, and lawless men—a ‘league’ dreaded and feared by good people but against whom they are powerless,” according to Strickland & Co.’s Almanac in 1859.

Upson, writing in 1884, also lambasted the vigilance committee. “It was such men as those composing the committee that ruled and finally ruined the South. Their inhuman outrages, perpetuated on good and loyal citizens, were the forerunners of the terrible war that soon followed, drenching the land in blood.”

In the end, Nott lost nearly everything he had loved. After serving in the Civil War as medical director of Confederal General Hospital in Mobile—and living through the deaths of two more sons, one to battlefield wounds and one to typhoid—Nott returned to defeated Mobile a broken man.

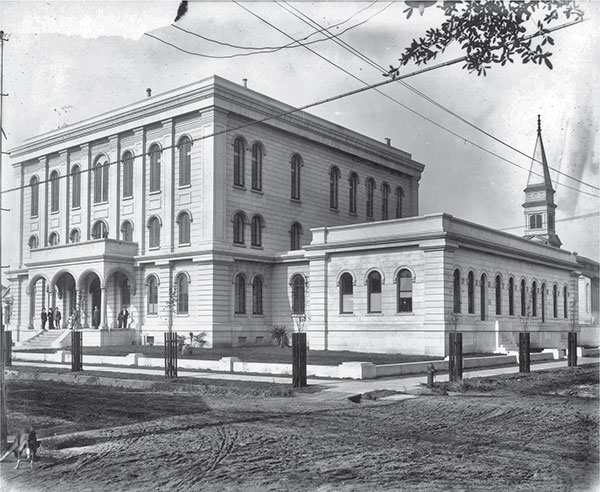

Perhaps perceived as the greatest indignity by Nott was watching the Bureau of Refugees, Freedmen and Abandoned Lands turn his beloved medical college into a school for Negro children. Nott had lobbied the Alabama legislature for years to start the school and raised $25,000 from wealthy Mobile merchants to kick-start the effort. He made a trip to Europe to personally buy medical equipment and other supplies for the school, which opened in 1859 with a faculty of seven and three hundred students.

Its transformation after the war drew lusty cheers from the Nationalist, a pro-Union newspaper in Mobile. “Think of it!” the paper wrote. “A school of upwards of 500 children, who, this time last year, were chattels, now citizens of America, and already rivaling many of the most privileged children of our land in their knowledge of the branches of a common school curriculum.”

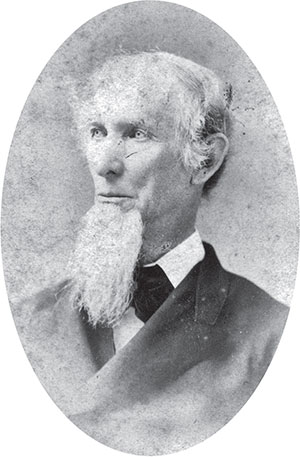

Dr. Josiah Nott was enraged when the Freedman’s Bureau turned his beloved Mobile Medical College into a school for newly freed black children. Doy Leale McCall Rare Book and Manuscript Library.

It would be an understatement to say that Nott disagreed.

“I confess, it does not increase my love for the Government when I pass by every day or two and see two or three hundred negroes racing through it and tearing every thing to pieces—the chemical laboratory is occupied by negro cobblers,” he wrote in an 1866 letter to a northern friend, Ephraim George Squier.

Nott wrote that he would “rather see the buildings burned down than have it used for colored children.”

The previous December, Nott was even more blunt to Squier in his assessment of Mobile in the hands of Union troops and his continued belief that blacks were doomed to permanent inferiority: “God Almighty made the Nigger, and no dam’d Yankee on top of the earth can bleach him.”

By January 1867, Nott had given up on his native South.

“I hope to leave the Negroland to You damd Yankees—It is not now fit for a gentleman,” he wrote to Squier.

Nott did leave. He moved to Baltimore and then to New York City, where he lived for most of the rest of his life. He returned to Mobile after becoming sick with tuberculosis in 1873 and died on his sixty-ninth birthday on March 31. He was buried along with six of his children.