PRACTICE 6

DO YOU EVER REACH THE END OF THE DAY AND FEEL AS THOUGH NOTHING OF REAL VALUE HAS BEEN ACCOMPLISHED?

If so, you may want to consider

PRACTICE 6: AVOID THE PINBALL SYNDROME.

When you don’t avoid the pinball syndrome, your room may feel like Sartre’s hell because:

• You don’t realize where you’ve ended up until it’s too late.

• You’re so busy fighting fires, you spend no time preventing them.

• You never beat the pinball game and often end up feeling like the ball.

Melissa cared about being a positive influence in the world. She had worked diligently over a career spanning nearly two decades, and now led a critical channel for the organization and had several direct reports. So I was a bit surprised when Garret, a longtime member of her team, approached me. “You know I think Melissa is a good person,” he confided, something obviously weighing heavily on him. “I really do appreciate her on many levels. But I have some concerns about how we work together. And to be honest, for the first time in ten years, I’m starting to think about moving to a different department.” He shared more with me and gave me permission to talk to Melissa after she’d canceled several appointments to meet with him. And that was the kind of thing he’d been experiencing. He went on to inform me that he wasn’t the only person feeling this way. It confirmed some patterns I had also noticed. I thanked Garret for his candor and decided I’d approach the subject with Melissa at a scheduled meeting we had the following day.

We met in my office, and after a couple of minutes exchanging pleasantries, I asked Melissa if she was okay if we used the time to discuss an issue not included on our agenda. “Of course,” she replied. If she was sensing something was amiss on her team, she wasn’t showing it. “There’s plenty on my to-do list, but I can always spare a few minutes for you.” I smiled at that comment—I’d had plenty of people say something similar over the years, but with Melissa, it was always sincere. It was part of her charm, which made the topic of our discussion even more perplexing.

“Thanks,” I continued. “I’ve been hesitant to share this feedback because I wanted to make sure I really understood what I wanted to convey. I hope you know that my only intent in sharing this with you is to help you be successful.”

“Okay,” Melissa said, leaning forward in her chair. “You’ve now got me a little nervous. But go on.”

“Garret came to me yesterday and shared some concerns he and other members of the team are having. He’s so frustrated that, after ten years of working here, he’s starting to think about switching to a different department.”

“Wow! You know that’s the last thing I want.”

“I do, and I’d like to help if I can. Do you mind if I share some observations?”

“Of course not.”

“So Melissa, what I see in you is someone who’s passionate about her work and the company, and you have absolutely no ego despite your many accomplishments. And while you consistently hit your department goals, I think you may be losing the hearts and minds of your team along the way.”

Melissa frowned. “Garret said all that?”

“Not in so many words, but I think it accurately reflects how he’s feeling. And while I don’t believe anyone questions your intentions, there is a sense that you choose to focus on tasks over people. I wonder if that is why you end up canceling so many meetings with your team members. One of the reasons Garret came to me was he couldn’t get on your calendar.”

“I’m really sorry to hear that,” Melissa replied as her phone gave off a ping. She glanced down at the message, and I waited while she scanned it before silencing her device. “Sorry about that, but you see how busy things are. In a perfect world, I’d love to have regular one-on-one meetings with everyone on my team, I really would. But that’s just not reality. Honestly, I don’t have the time.”

• • •

On a recent drive to work, I couldn’t help but notice a driver in the next lane who seemed to be in a tremendous hurry. At each intersection, we both waited for the light to change. But at the first sign of the green light—as if we were competitors at a drag strip—he punched the gas, lurched across the intersection, and raced toward the line of cars in the distance. I, however, accelerated at a pace appropriate for someone whose idea of thrill-seeking is staying up to watch late-night television. When I reached the line of commuters ahead, I pulled next to the anxious driver (whose own quarter-mile sprint hadn’t taken him past the upcoming traffic or light) and waited for the light to change again. I glanced at the man through the corner of my eye and saw him pressed forward in his seat, staring at the stoplight as if he could turn it green through an act of sheer willpower. The light changed and the man raced ahead. I caught up to him yet again. This back-and-forth continued for some time as we moved from light to light, one intersection at a time. I wondered if the driver would ever see the futility of his approach.

The experience made me think about how often we chase after metaphorical stoplights in our own lives, stomping on the gas and racing ahead block after block, without even noticing the impact on others around us. What if such a hyperfocus limits us from stepping back and examining the road itself? And just where is that road taking us? It was with such thoughts that I considered a former associate of mine at a previous company. The occasion was his funeral.

On a gray winter afternoon, I pondered the life of the man being laid to rest. He had invested most of his life in a company he founded and had been recognized for many professional accomplishments. Starting a company takes a lot of time; urgencies abound, and a focus on the immediate can make the difference between a company’s success or failure. I reflected on a conversation we’d had many years before, when he mentioned that while he intended the urgencies to be temporary, they had regrettably become a way of life. His “season of imbalance,” as he liked to call it, had extended to over thirty years.

As I listened to what seemed to be perfunctory remarks about himself and his devotion to his job, I was struck with the notion that in two or three days, life would continue. The to-do lists, the meetings, the client visits, and all the activities that made up his workday would matter-of-factly be picked up by somebody else. The job would go on. I then took note of the man’s family: His adult children sat stoically as the mostly generic eulogy was delivered, and his estranged ex-wife sat with her new husband. Behind them, rows of conspicuously empty seats marked the poor turnout. Here was the funeral of a man who had worked hard to rise to an important and respected position—traveling the world, managing teams, and, by some accounts, finding success. However, looking at his family, it appeared that all his professional accomplishments and all the urgent to-dos seemed to have come at a heavy price.

I contrasted this experience with another funeral I attended earlier in the year. The woman being laid to rest had worked in an administrative-support role at her company. She’d never held a prominent title, managed others, or traveled to some interesting locale on company business. Yet, she seemed to embody the very principles I’ve sought to write about in this book. Her family had even gone to great lengths to accelerate and reschedule the wedding plans of her son so she could attend that important event before her death. The funeral service was packed with co-workers, friends, family, and those whose lives she had positively affected. Gratitude and love permeated the gathering as story after story illustrated how this unassuming woman had invested in others. And while saying goodbye to her was difficult, everyone who attended the funeral walked away with the impression that this beautiful soul had left behind a life well lived.

Reflecting on the funerals, it occurred to me that the main difference between these two people was how they had prioritized. One had unintentionally allowed urgencies to come at the expense of important relationships. The other one had made relationship building a part of her life’s work. It made me wonder: What distracts us from those things we’ve decided are truly important? Why are we willing to exchange the timeless for the transitory? Giving in to the allure of the urgent over the important is what I call the pinball syndrome.

Think back to the last time you played a pinball game. While there are plenty of pinball apps available, I’m thinking specifically about the games that had their heydays in the late seventies and early eighties. These were masterfully crafted machines, representing a blend of the fantastical, mechanical, and electronic. Here’s how they work: The pinball player’s goal is to use two or more flippers (small movable bars) to launch a metal ball into numerous physical targets, accumulating points, and unlocking various rewards. These visually beautiful games are designed to engage the senses: Lights flash as large scoreboards track progress, while bells ding, bumpers thump, and the ball clacks and rolls across wood and metal tracks. It’s a very visceral experience, and it’s easy for the sights and sounds to drown out one’s senses and demand complete attention. Eventually, gravity will win the day, however, as the ball slips past the frantically swinging flippers and drops out of sight. But fear not, for there’s always a new ball ready to ratchet into place. All we have to do is pull the plunger back and send it on its way.

The truth is that with practically every worthwhile job or career, we can all get caught up in the pinball syndrome. Think of a pinball machine as a metaphor for all the urgent things that demand our attention throughout the day. And while we may not feel like we’re playing a game, per se, when accomplishing such tasks, we might feel attracted to (or even seduced by) the rapid pace and focus that’s required to get them done. Add a small endorphin rush as we check off the next item on our to-do list, and it’s easy to see how the urgent can feel gratifying, even addictive at times. The challenge is that some of the urgencies might also be important, but the allure of the game gives everything equal weight. As a result, we can end up spending time and energy on the less important. In the words of author J. K. Rowling’s Albus Dumbledore, “Humans have a knack for choosing precisely the things that are worst for them.”

Urgent things act on us; they compete for our attention and insist on a response. Consider the horrific example of Eastern Air Lines Flight 401, bound from New York to Miami on December 29, 1972. The jumbo jet had a full load of holiday passengers as it began its final descent toward the Miami International Airport. When the crew pulled the handle to lower the landing gear, one of the lights failed to turn green.

In this case, the nose-gear light had remained off, meaning that either the nose wheel hadn’t safely come down and locked into place, or that the bulb itself had burned out. The pilot radioed the control tower: “Well, ah, tower, this is Eastern 401. It looks like we’re gonna have to circle; we don’t have a light on our nose gear yet.”

The tower directed the plane to change its approach and climb back to two thousand feet. They set the autopilot to a looping racetrack pattern and turned their attention to the light. The captain and the first officer attempted to replace the bulb, but discovered that the cover had jammed. After working unsuccessfully to get it out, the engineer joined in, but likewise couldn’t get the light to budge. The copilot suggested they use a handkerchief to get a better grip, but whatever they ended up trying didn’t help. The engineer finally suggested pliers, but warned that if they forced it, they could end up breaking the mechanism. The crew kept at it, throwing out expletives as they struggled to get the light bulb out and replaced with another.

The cockpit voice recorder captured the second officer next,7 “We did something to the altitude.”

“What?” the captain replied, confused.

“We’re still at two thousand feet, right?” the copilot asked.

The captain then uttered his last words: “Hey, what’s happening here?”

The microphone captured the sounds of the airliner flying itself into the Everglades, taking the lives of 101 passengers and crew.

The final report cited pilot error as the cause of the crash, citing that “the failure of the flight crew to monitor the flight instruments during the final four minutes of flight, and to detect an unexpected descent soon enough to prevent impact with the ground. Preoccupation with a malfunction . . . distracted the crew’s attention from the instruments and allowed the descent to go unnoticed.”8

While this example is extreme, solving the problem of the landing-gear light was certainly urgent. Landing the airplane safely, however, was of paramount importance. Unfortunately, in their zeal to address the urgent, the crew got distracted and unintentionally lost sight of what mattered most.

In the workplace, urgencies tend to be easy to identify, like picking up the phone, answering a text, or clicking an email. But as the example of Flight 401 illustrates, the tendency to confuse what’s urgent with what’s important can have long-standing consequences. Like the next ball being served up to us by the pinball machine, it’s a constant press of urgencies that act on us: They vie for our immediate intention. By contrast, important things often require us to act on them. Important things are those that contribute to our values and align to our highest goals. They are intentional and long-term rather than ad hoc and transitory. In almost all cases, they include important relationships.

The nature of the pinball syndrome is to confuse urgency with importance. And since organizations often reward urgent behaviors (because by their very nature they’re easy to recognize), work can provide a powerful incentive to pull the plunger back and play round after round. Of course, urgencies will come up that require our attention. Many things are both urgent and important. When I talk about avoiding the pinball syndrome, I’m not advocating that we step away from the game altogether, but rather, that we differentiate between when we must play and when we choose to play. The pinball game is rigged and, in the end, will eventually have its way. Despite whatever totals we’ve racked up on the scoreboard, or the long hours we’ve devoted over nights and weekends, the ball eventually slips through. Any win is temporary at best, and we’re only given a small respite before the score resets and the next ball ratchets into place. It’s what we do in that moment—between reaching for the plunger and taking our hands off and stepping back—that will make all the difference. At its core, it’s the same difference between the two funerals I attended: a man who played a seemingly never-ending game for the illusion of a high score, and a woman who chose to step away from the game and connect with the people standing around her. Resisting the allure of the game isn’t easy. It requires that we delay gratification and take the long-term view. With that in mind, here are two suggestions that may help:

• Set goals that matter. Reflect on what’s important to you at the deepest and most meaningful levels. Be specific. This process is how a GPS works—we need to identify a destination first to calculate which roads will get us there most directly. The more exact the address, the better the chance we’ll arrive. Goals that matter are those that are typically centered on strengthening relationships, planning for the future, and personal improvement.

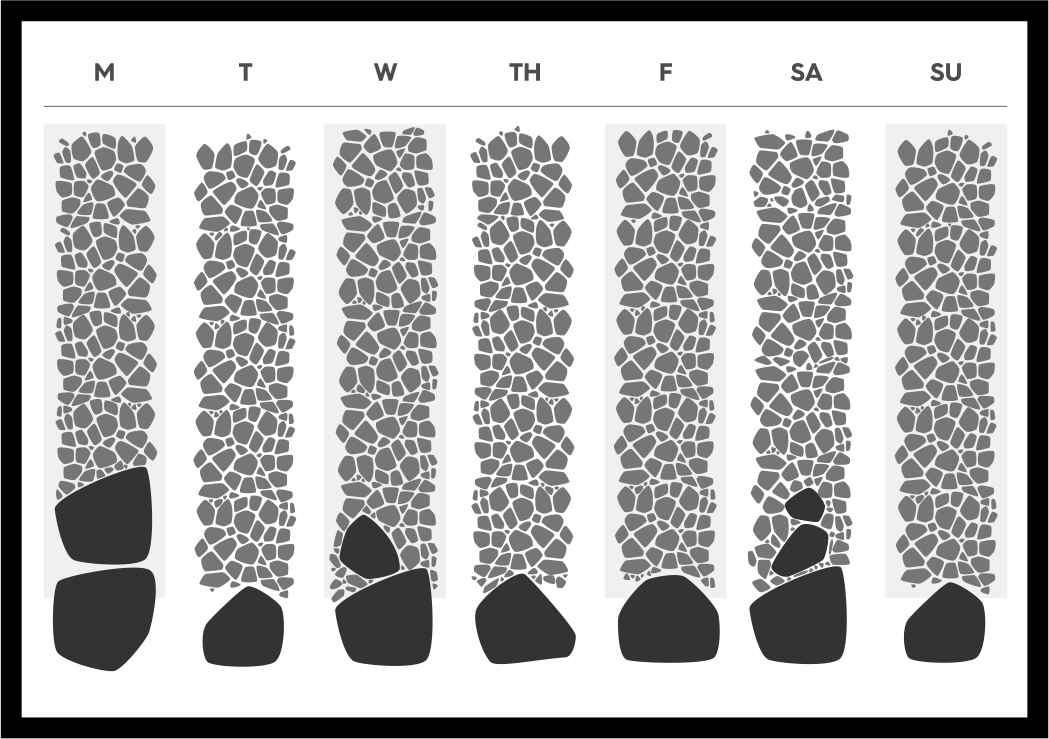

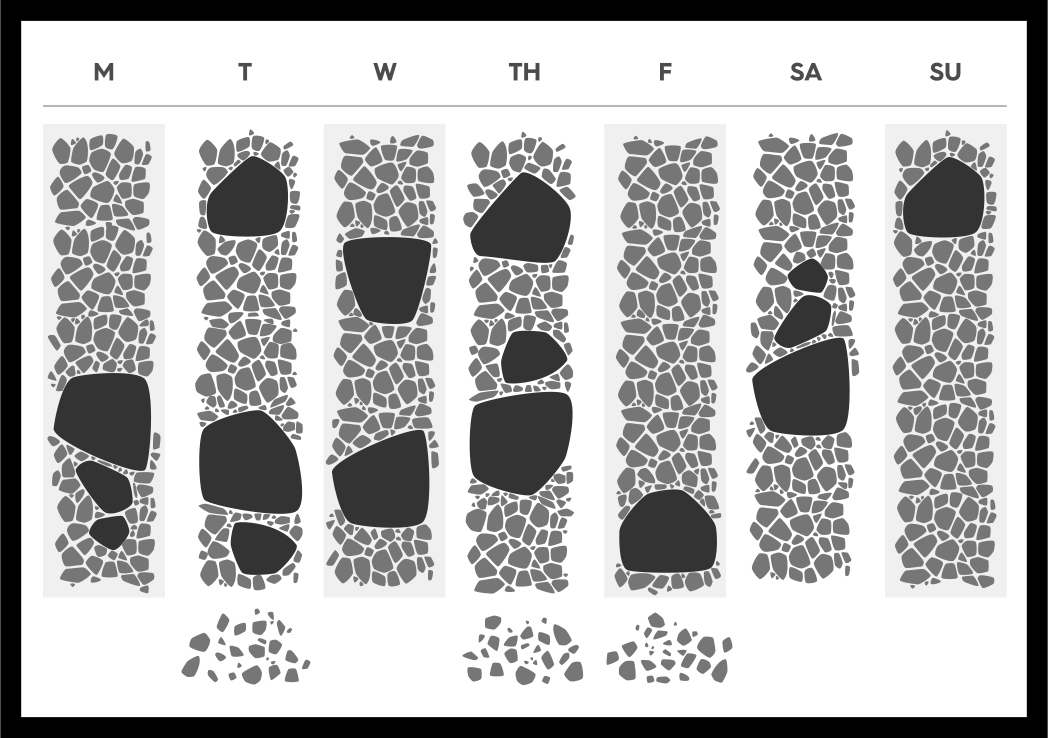

• Choose your weekly priorities carefully. Rather than just a to-do list, think about which activities will have the greatest impact on your relationships and the outcomes you care most about. Consider which actions would build trust, make work easier for people, help you be more patient in your dealings with others, or create value for your customers. Try thinking about your weekly calendar as rows of empty containers, each limited by a finite amount of space (i.e., time). People who suffer from the pinball syndrome kid themselves into believing they can fit everything in—all the numerous small and urgent tasks along with the fewer, more valuable and important ones. We tend to focus on the quick wins first, shoving as many urgent tasks into our limited containers as we can. And although the containers are full, they’re not often filled with meaningful accomplishments. But here’s the problem: Once these limited spaces fill up with urgencies, the important things naturally fall by the wayside. When represented in a calendar, these containers filled with urgencies look something like this:

If we thoughtfully identify and schedule the most important things first (the priorities that require us to act on them rather than react to them), what falls by the wayside are the urgent, less important things. And because they’re less important, we won’t get derailed if they don’t get done right away.

I have a reminder of the pinball syndrome enshrined in my office. Several years ago, our people-services team brainstormed ideas to improve the culture at our corporate office. At the time, people were working hard, but they didn’t seem to be enjoying it much. We came up with four initiatives to focus on and captured them on my office whiteboard. We had great passion and enthusiasm for the list, but as we returned to our work, we were inundated with all the typical urgencies. We talked about the list for weeks but, after a while, we stopped noticing it altogether. Three years passed, and I still resisted the urge to wipe the list from my board—hanging on to the hope that we’d get to it sometime. It was important, after all. Eventually, I surrendered. Somewhat discouraged, I went to erase the list, only to find it wouldn’t come off! Even though it had been written with a dry-erase marker, the list had been there so long that it had become permanent. Our team had fallen prey to the pinball syndrome. We became so caught up in the urgent that we didn’t focus on the things that might have made the greatest impact on our culture. And now I had a permanent reminder of what that looked like.

Often urgencies show up as things, but people can pull us into the pinball syndrome as easily as a to-do list. Let me share a few strategies I’ve learned that can prevent us from getting sucked into people-created urgencies:

• Block your schedule. Purposely carve out as many blocks of time as you can each week to deal with unplanned events or crises that might surface. Let everyone around you know at the beginning of the week when you will be available. If no unexpected crises surface, you’ll get the benefit of a few extra minutes to focus on the important, nonurgent things like strategic planning, relationship building, forecasting, crisis prevention, and raising teenagers.

• Reflect on your day. Look back over the day and ask what worked and what didn’t, then make a resolution to handle things better the next day. The purpose of such reflection is to learn, not to beat yourself up over what you failed to do.

• Be ready for drop-ins. Rehearse language to use when people drop in with their issues and urgent requests. If I’m asked to take on a sudden new project, my response might be: “Here’s my challenge. I absolutely want to be helpful. But I also want to be realistic about the commitments I’ve made to other people. Let me give you an idea of what I think I can realistically do.” Sometimes when someone asks me if I have a minute to talk, I honestly respond, “I do have a minute, but I don’t have five. Can we handle this in a minute? If not, let’s schedule a time when we can give it the attention it deserves.”

One of the sinister aspects of the pinball syndrome is that it can ensnare any of us, which was what I suspected was happening with Melissa . . .

• • •

“I hear you, Todd, I really do,” Melissa replied as her phone gave off a ping. She glanced down at the message and I waited while she scanned it before silencing her device. “Sorry about that, but you see how busy things are. In a perfect world, I’d love to have regular one-on-one meetings with everyone on my team, I really would. But that’s not my reality. Honestly, I just don’t have the time.”

It was a classic response from a talented and dedicated person stuck in the pinball syndrome. I could almost picture Melissa hovered over the game, doing her best to keep the ball in play, unaware that her team was surrounding her.

I reflected on my whiteboard with the now infamous unerasable list—I knew as well as anyone that it was easy to lose sight of what was important in the pinball syndrome. “Melissa, is keeping Garret on your team something that’s important to you?”

“Very much so.”

“Tell me more about what’s going on,” I asked.

“It’s so disheartening to hear how Garret is feeling. I really appreciate and value him as a member of the team. And I can see how having to cancel our appointments didn’t help any.”

“Tell me more about that, if you don’t mind? What happened?”

“Well, you know how it is at the end of the quarter. I get pretty swamped with demands from the various departments I support. Lots of last-minute requests and things like that.”

“Do you take that into account when planning your calendar? I mean, it sounds like you can pretty much predict this surge will happen at the end of every quarter.”

Melissa considered it for a moment. “Well, obviously, not as much as I should.”

“Tell me about your typical day,” I asked.

“Well, every morning I look at my to-do list and start working through it. I usually don’t get very far before something pops up. But that’s just the nature of the job, so I try and get as much accomplished as possible before the day’s out and then pick it back up again tomorrow.”

“Okay, so given where you typically spend your time and energy, how do you think Garret would see himself in your day-to-day priorities?”

Melissa hesitated, unconsciously glancing at her phone. “Honestly, I can see how he might think he’s unimportant. But that’s not how I feel at all.”

“I think you’re probably right,” I agreed. “I suppose the question is how can you change that?”

“I need to talk to him,” Melissa replied.

One of the causalities of living in the pinball syndrome is losing sight of where you end up. Despite her good intentions, Melissa had missed the cues that her team was growing frustrated.

“I think that’s good,” I said.

“But I don’t know how to solve my time issue.”

“Do you mind if I make a suggestion?”

“Of course not.”

“The way you describe your day, it’s like you’re in a never-ending battle to try and finish your to-do list.”

Melissa nodded. “It does feel like that.”

“It seems to be a given that you’re probably always going to be leaving something undone—as you phrased it, ‘to pick it back up again tomorrow.’ ”

“That’s true.”

“So maybe the question isn’t so much about how you squeeze more in, but what you let go? Maybe you’re allowing the urgencies to take precedence over what’s really important, such as your team’s need to spend more time with you.”

“I hadn’t really thought of it like that,” Melissa said, “but maybe you’re right. I could block out time for not only the end-of-quarter emergencies, but also for my team before the crises set in.”

“Try to build an immovable wall around the important things,” I continued. “It’s okay if the urgent but unimportant stuff slips a little.”

“I guess it’s hard to give yourself permission to do that—at least for me, anyway.”

“I think probably for all of us,” I agreed, doing my best not to glance back at my whiteboard. When Melissa left, I felt optimistic that she was going to start resisting the allure of the pinball syndrome and invest more in her team. And I was going to request a new whiteboard.