PRACTICE 7

DO YOU ONLY SEE YOUR ABILITY TO WIN OR SUCCEED WHEN IT COMES AT THE EXPENSE OF OTHERS? OR DO YOU TAKE CARE OF EVERYONE ELSE AT YOUR OWN EXPENSE?

If either of these is true, you may want to consider

PRACTICE 7: THINK WE, NOT ME.

When you don’t “think we, not me,” your room may feel like Sartre’s hell because:

• You live with the fear that there’s never enough, perhaps resenting others around you when they succeed.

• You achieve short-term wins at the expense of genuine, long-term successes.

• People will want to exit your room as fast as they can because they don’t want to live or work with a martyr.

Because a major part of my job involves listening to people all day long, if I have a free moment, I may choose to eat lunch by myself for a little down time. Those who are particularly adept at squeezing in an impromptu, unscheduled meeting have been known to lie in wait and ambush me during such unguarded moments. I’m not sure that’s what Lewis, a mid-forties senior manager who oversees a large sales territory for the organization, had in mind, but he was definitely making a beeline in my direction.

“Hey, Todd,” he announced as he approached, sounding more anxious than enthusiastic. “I’m glad I ran into you. You have a moment?”

“Sure,” I replied, realizing my alone time would need to wait.

“I appreciate it. I’m struggling with something, and I hoped I could talk it through with you.”

“No problem. Do you mind if we talk while we walk?” I asked, wanting to get a little fresh air. Lewis agreed, and we started to walk around the campus. “So, what’s going on?”

“We’ve got a compensation problem,” Lewis replied. “You know I appreciate my job and that I’m well paid, but I’m struggling with the fact that one of my direct reports is going to make more than I will this year.”

“Can you tell me more?” I asked.

“It just doesn’t feel right. I mean, why would anyone aspire to my position if their direct reports can make more money than they do? Frankly, I don’t think we should have a situation where a subordinate makes more than his or her boss. And that’s what’s happening with Brenda.”

“You don’t think Brenda’s performance is up to par?” I asked. Brenda was a particularly talented salesperson who had been doing a terrific job in the territory.

“You misunderstand,” Lewis corrected. “It’s not about Brenda’s performance—it’s about the fact that she’s making more than I am!”

• • •

We live in a competitive world—our educational, corporate, sports, and legal systems (just to name a few) encourage and reward us to one-up each other, reach the top of the bell curve, land in the uppermost percentile, score the most points, or add the definitive “W” to the win column. In one of our well-known workshops, we begin with a game to help people understand just how invested they are in winning. The facilitator introduces the game saying something like this: “Most kids love to play Tic-Tac-Toe. Was that true for you?” Usually everyone nods in agreement. The facilitator then asks the participants, “So, what was the point of the game when you played it as a child?”

“To win as fast and as often as you could!” most program participants respond.

At that point, the facilitator asks people to pair up and play a few rounds of a new game, saying, “So the game we’re going to play isn’t exactly Tic-Tac-Toe, but something very similar called Extreme Tic-Tac-Toe. Every four items in a row achieved (x’s or o’s), yields one point. If you finish the first game during the allotted time, immediately start a new game. Remember, the goal is to win as fast and as much as you can!”

The first round often ignites the competitive win conditioning many of us grew up learning. Individuals start to pit themselves against one another, working furiously to beat their partner by increasing their individual score. At the end of Round One, each pair shares the total points they achieved. Most pairs get only a few points, since they have been competing.

The facilitator then gives each pair time to strategize before the second round, emphasizing that the goal is to win as fast and as much as you can. Gradually, the partnerships begin to realize they don’t have to fight each other for points. Rather, they can work together to accumulate points. They see that they can work faster and more efficiently cooperating instead of competing. Once they have this “aha” moment, they start to fill up their game cards as fast as possible. After the second or third round of the game, the partners get four, six, or even ten times the number of points they did working alone.

As human beings, we’ve been conditioned to view the world as having only so much to offer, so we’d better get ours while we can. I remember a colleague once sharing with me how difficult the holiday season was for him as a child. When I inquired as to why, he answered, “Because as I watched my siblings retrieve their presents, I thought to myself, Well, there’s one less for me. And I had a lot of siblings!”

For my colleague (and for many of us), we resign ourselves to live with a win-lose mentality: If you get a present, I don’t. There are several other mindsets when it comes to how we live and work with others:

• Lose-win

• Lose-lose

• Win-lose

• Win-win

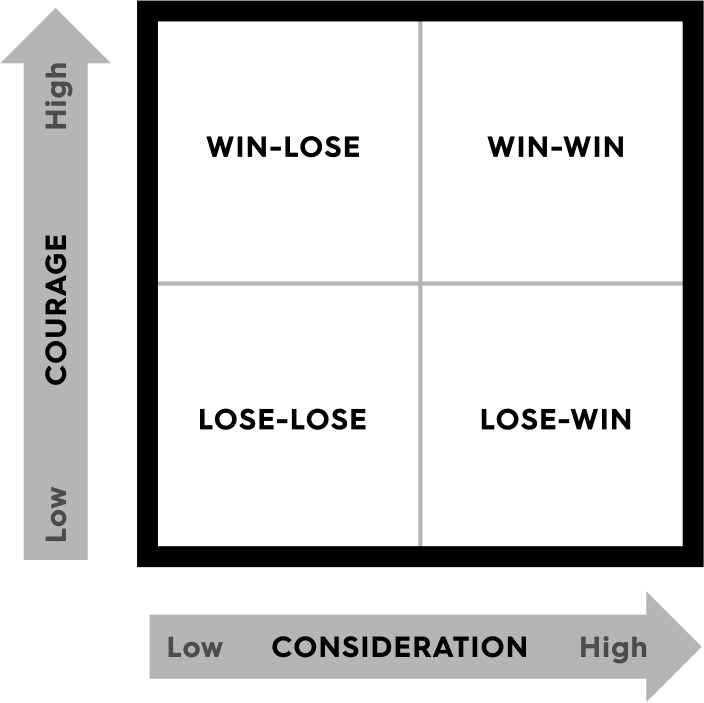

These mindsets are largely driven by two factors:

• The nature of our maturity level.

• The amount of courage and consideration we employ when dealing with others.

At FranklinCovey, we teach about three levels of maturity: dependence, independence, and interdependence. Dependence comes with the mindset of “you.” You are responsible for me, for my feelings and circumstances. It’s your job to take care of me. We all experienced this level of maturity when we came into this world. As infants, we were dependent on our caregivers for everything: food, clothing, shelter, and love. There’s nothing wrong with being dependent in certain situations. But how many of us have worked with adults who are still stuck in dependent behavior: They believe that you or others are responsible for their successes and failures, their moods and feelings. Dependence represents the lowest level of personal maturity, where we can consign our happiness to others or adopt a victim mentality when things go wrong. It often sounds like you let me down, you make me so mad, you didn’t come through, it’s your fault.

However, when we take on a new role or skill, there is a period of time during which it’s expected that we’ll be dependent on others to teach us as we learn that new skill. Many years ago when I first became a physician recruiter in the medical industry, I had no training in the field. I was reliant on other professional recruiters to learn the ropes. You could say I was dependent on them. But little by little, I learned and grew in maturity.

Independence, the next level of maturity, comes with the mindset of “I.” Independence sounds like I am the one who can do this, I am responsible, I will decide what’s best. When we think and act at this level, we move our focus from the people around us to our own strengths and capabilities. For many of us, we think independence is the pinnacle of maturity. Once I had a few years’ experience building my knowledge and skills as a physician recruiter, I began to see myself as highly successful. I thought I had arrived. What more was there to learn? (See “Practice 15: Start With Humility.”)

While independence is certainly more mature than dependence, there’s something even more satisfying and transformational that happens when independent people choose to work together.

With interdependence, we adopt the mindset of “we.” When we think and act interdependently—we make a choice to combine our talents and capabilities with those of others, creating something even greater as a result. Interdependence sounds like together we can do it, together we can collaborate, and together we can figure this out. I remember attending my first industry convention where I met other successful professionals who had been in the business far longer than I had been. It was then that I came off my big independent throne and realized just how much I had to learn from others.

Many studies seem to suggest that nature uses cooperative strategies and not just survival of the fittest. There’s something innately powerful about cooperation, about banding together and leveraging each other’s strengths.

The most effective way to strengthen our relationships and find win-win is by seeing and adopting the mindset of interdependence. If we’re not careful, when we’re in situations that can trigger reactivity, we can drop to independent, or worse, dependent behavior—blaming and accusing others or holding others responsible for our emotional well-being. Here’s how not having an interdependent mindset played out for me.

Some years ago, a colleague completely rewrote an important presentation I had prepared. When I looked at the changes, negative thoughts came flooding in: Who does she think she is? I’ve been doing this for years, and suddenly she’s the expert? Maybe she should just do the entire thing herself! I assumed bad intent, questioned her motives, and fell into a victim mentality. I was focusing on how she made me mad—living in a state of dependence. I had allowed the situation to become a competition between me and my colleague.

Later, I began to feel even more defiant: I’ve received plenty of accolades, and I don’t need anyone else’s feedback. I know what I’m doing. I just need to press forward and forget about her. I had slipped into the independent level of maturity, seeing my colleague as an obstacle standing in the way. I was prepared to double down on my own capabilities and dismiss her feedback altogether.

But the next day, I shared what was happening with a trusted friend. He listened patiently as I ran through my own plans and litany of complaints. When I was done, he replied, “I can imagine how difficult it would be to hear criticism about your performance after all the work you’ve done. I also want you to know that your ability to engage an audience is one of the primary reasons you’re asked to deliver these presentations. You’re good at what you do, Todd.”

His sincerity started to soften the defensiveness I was feeling. He continued, “Putting aside the somewhat abrasive way she chose to share her feedback, I actually believe some of her comments would make your presentation better. It might be helpful for you to separate how you’re feeling about the feedback from some of her potentially useful suggestions. I can tell she wants you to emphasize a few key points because it will make the presentation more persuasive. Her idea to start the presentation with the inspirational quote will help the audience understand the concept faster.” He shared a few other points I was unable to hear the day before.

He got me thinking, Was it possible she wanted to help make my presentation the best it could be? Certainly, she had a vested interest in the outcome. Perhaps there was more to be gained by working together rather than separately . . .

My friend’s wise coaching allowed me to put my defensiveness aside and genuinely consider the feedback. He concluded, “I honestly believe her heart is in the right place. Her technique may not be that great, but her intent is unquestionable—she wants to help.”

With an interdependent mindset, my friend helped me push my ego aside and dive into what my colleague had suggested and why. While I didn’t accept every suggestion, I came to realize that many of her recommendations made the presentation stronger. I even asked for another meeting with her to rehearse what I’d learned. I chose to work interdependently. When it came time to deliver the presentation again, it was much improved. Since then, I’ve asked for her advice on other presentations I’ve been tasked to prepare and deliver.

Those who consistently model interdependence balance courage and consideration when working with others. We define courage as the willingness and ability to speak our thoughts respectfully, and consideration as our willingness and ability to seek and listen to others’ thoughts and feelings with respect. While it’s challenging to maintain a perfect balance of both in every situation, the real thing to look for is to make sure you’re not dramatically weighted toward one side or the other. Too much consideration without enough courage can turn you into a so-called pushover or doormat. Too much courage without enough consideration can turn you into a bully.

Too Much Courage

Years ago I worked with a man whose reputation preceded him. He had a rough exterior, a short temper, and interrupted people constantly. When he disagreed with something or shared feedback with others, he gave no thought as to how his offensive style would make them feel. You can imagine how excited I was when I was assigned to work with him on a critical project.

As we started to orchestrate the team, every person I recommended was immediately shot down by him: “He’s an idiot.” “She doesn’t have any clout.” “He’s not right for the job.” And so on. Lacking courage wasn’t his issue. The following six months of the project were the longest in my life. Surprisingly, we finished the project on time, but no one wanted to work with him again. And he continued as a lone genius for the rest of his career.

Too Much Consideration

In a previous career, I worked with a person who had nothing but consideration. He would run other people’s errands on his lunch hour, always worked long hours, and volunteered to do others’ assignments on the weekends, even tasks that were outside of his job description or areas of responsibility. Sensitive to any negative feedback, he avoided saying no to anyone. While he was well liked (who wouldn’t like him, he never said no!), he lacked the courage to speak his opinions with confidence and told me he didn’t always feel respected. Over the years he became exhausted, demoralized, and felt underappreciated by everyone.

While great ideas and high courage can be critical to doing a job well, without consideration and respect, the only team you will find yourself on is a team of one. On the other hand, with high consideration but no courage, you may be well liked but will ultimately feel disrespected. Like the highly courageous person who alienates others, the highly considerate person may also feel alone.

The challenge is to demonstrate high courage and high consideration equally across all relationships. Sometimes we’re more courageous at home than we are at work, or more considerate with our professional colleagues than we are with our personal relationships. When we strive to balance both equally, we pave the way to interdependence and mutually beneficial outcomes in all relationships. How we choose to view and work with others leads to one of four outcomes. Let me illustrate by using the story I shared earlier—the one in which I felt my colleague was rewriting my presentation.

• Lose-win (high consideration, low courage). I concede that my colleague is right in rewriting the presentation and that I’m wrong for questioning her. I capitulate to her thinking and accept her changes universally, taking the path of least resistance.

• What lose-win looks like:

- I lack courage to express or ask for what I need.

- I’m often intimidated—I give in easily.

- I’m motivated by acceptance from others.

- I tend to hide my true feelings about things.

• Lose-lose (low consideration, low courage). Feeling attacked and belittled, I’m completely justified in trashing the entire presentation—her version and mine. Not only am I not interested in what my colleague says, but I’m willing to abandon my work as well. Somebody else can waste time on it if he or she wants to, but I’m through. And too bad if she can’t find a replacement at this late date.

• What lose-lose looks like:

- If I’m going to lose, so are you.

- I’m willing to be hurt, so long as you are too.

- I give up on what’s really important.

• Win-lose (high courage, low consideration). Since my colleague fired the first shot and attacked me, I’m perfectly justified in doing the same. I’ll just hit “reject all” on her revisions, then craft a lengthy email and give her a piece of my mind. She needs to be put in her place.

• What win-lose looks like:

- I use position, power, credentials, possessions, or personality to get my way.

- I put down others so I look better.

- I compete rather than collaborate.

- I’m going to win and you’re going to lose.

• Win-win (high courage and high consideration). I’m going to considerately and respectfully listen to my colleague’s point of view and courteously share my own view, assuming good intent. I’ll make the choice to work together, knowing we both have strengths to contribute and that we’ll achieve a better outcome as a result.

• What win-win looks like:

- We work together until we find a solution that benefits both of us.

- I value your needs and desires equally to my own.

- I collaborate rather than compete.

- I balance courage and consideration when communicating.

- I can disagree respectfully.

In my experience, the long-term impact of any outcome other than win-win will sooner or later be headed toward lose-lose.

There’s tremendous power in thinking we, not me. Not only are we more likely to achieve the results we want, but we strengthen relationships along the way—something I wondered if Lewis, the senior manager who was concerned over the compensation of one of his direct reports, had lost sight of.

• • •

“You misunderstand,” Lewis corrected. “It’s not about Brenda’s performance—it’s about the fact that she’s making more than I am!”

“It sounds like you’re seeing this as a competition,” I replied as we continued our walk, “that the winner here is the person who ends up making the most money.”

Lewis considered that for a moment before replying. “I think it’s about fairness, not about a competition.”

“Okay, let’s go with that then,” I continued. “Don’t you benefit when Brenda performs well?”

“Sure,” Lewis answered. “I mean, I own the number for the entire area and her contribution helps me hit my target.”

“So you make more when Brenda performs well and you more easily hit your goals—maybe even sleep a little easier at night knowing that particular part of the region is performing.”

“Yeah,” Lewis admitted.

“And meanwhile, Brenda continues to be motivated to work hard and grow the region even more. Let’s say we restructure the compensation plan in your area to keep Brenda from performing past a certain ceiling. How do you think she’d respond to that?”

“Well, she of course wouldn’t like it,” Lewis replied. “She’d probably be tempted to coast once she hit the cap.”

“Would she be frustrated enough to move elsewhere?” I asked.

“I hope not, but you never know. I guess she might start looking.”

I paused and stared at Lewis. “And how is that good for you? To me, it sounds like a lose-lose. You may make a point about compensation, but in the end, it would hurt both of you. Is that really what you want?”

Lewis sighed. “No. It’s just the principle of the thing.”

“You know there are two other senior sales managers who have team members making more than they are making, right? They actually revel in the fact that they have the kind of people working for them who can earn so much. The truth is, if Brenda happens to take a bigger slice of the pie, she’s not taking it off your plate; she’s made the entire pie bigger for everyone. That seems like a win-win to me.”

“Maybe,” Lewis admitted.

I continued, “You’ve been a good leader. You’ve mentored her over the years and helped her get where she is. That’s worth something. Is money the only way to calculate success?”

“I guess not,” Lewis said.

“One option would be for you to go back to a pure sales role. You’d probably make more money as a result. But that would mean giving up leading your team—which you’re great at, by the way, and something I think really matters to you.”

“No, you’re right. I don’t want to give that up. Maybe I’m losing sight of the other rewards besides just money.”

“Why not mentor each salesperson on your team to the point where they become so successful that their compensation passes yours.”

Lewis nodded. “I’ll have to think about that.”

While Lewis continued to struggle with Brenda’s pay, I’ve seen other leaders take great pride in watching their team members’ financial successes model the spirit of think we, not me.