Also Known as Love

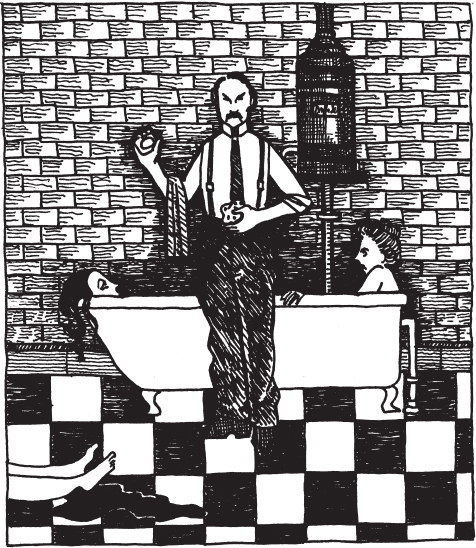

Consider, friends, George Joseph Smith,

A Briton not to trifle with;

When wives aroused his greed or wrath,

He led them firmly to the bath.

Instead of guzzling in the pub,

He drowned his troubles in the tub.

—Ogden Nash, “They Don’t Read De Quincey in Philly or Cincy”

Although two hundred miles separate 16 Regent’s Road, Blackpool, from A 14 Bismarck Road1 in the North London suburb of Highgate, and sixty miles separate the latter address from 80 High Street, in the Kent town of Herne Bay, the three places have a gruesome fact in common—a fact that, with others, came to light early in 1915, capturing the attention of newspaper readers to such an extent that reports concerning hostilities with the Boche were on some days, in some papers, given second billing on the front page.

One supposes that the most avid readers of the accounts of how people had taken a bath but not lived long enough to dry themselves were women, young and not so young, about to embark on matrimony; and their mothers, fearful that, in gaining a son-in-law, they might be losing a daughter for good and all. Perhaps some of the more apprehensive mothers added to their birds-and-bees advice the warning that, at least during the nuptial period, their daughters should forget that cleanliness is next to godliness and steer clear of bathtubs.

The man whose activities had caused the maidenly and maternal worries about the cause-and-effect relationship between personal hygiene and sudden death was born in Bethnal Green, a sleazy district of East London, in January 1872. He was christened George Joseph Smith.

His first name was also that of his father, who was an insurance agent. If the father was at all good at his job, presumably he was a slick talker—and if so, then George junior’s power to charm the birds was partly inherited. Only partly, though. Considering how, by the time he was in his midtwenties, he was using—or rather, misusing—women, he must have practised the deceit of blandishment, learning from trial and error, so that an innate talent was disciplined and refined into something akin to genius.

You may sneer at the notion, but I am inclined to believe that the fatal fascination Smith exercised over women (truly fatal, so far as some of his victims were concerned) was in part measure optically induced. According to one of the lady-friends who lived to tell the tale, “He had an extraordinary power. … This power lay in his eyes. When he looked at you for a minute or two, you had the feeling that you were being magnetized. They were little eyes that seemed to rob you of your will.” Other women said much the same thing. And Edward Marshall Hall, the great barrister, once broke off an interview with Smith because he believed that an attempt was being made to hypnotize him.

But if Smith was a hypnotist, he either developed the skill in manhood or, possessing it earlier, displayed it only as a party trick during his formative years. Hypnotism, mesmerism, call it what you will, can hardly have played a part in his fledgling criminal schemes, the unsuccessfulness of which might have caused a less dedicated apprentice crook to make the best of some thoroughly bad jobs and seek a licit calling. Its final act apart, the story of the life and crimes of George Joseph Smith provides an object lesson to all aspiring villains: if at first you not only don’t succeed, but fail abysmally, try to find a novel method of fleecing.

By the age of ten, Smith had committed such an assortment of misdemeanours that it was decided that the community—and he, too, perhaps—would be far better off if he were in a reformatory. He was despatched to one at Gravesend (a name that might be considered portentous of his way of breaking off relationships in later life), and there he stayed until he was sixteen. Drawing no righteous morals from the experience, he was no sooner back with his mother—who was now living alone, whether widowed or deserted I cannot be sure—than he was being troublesome again. A small theft was punished by a sentence of seven days’ imprisonment. Out again, he took a fancy to a bicycle, and so was soon back in gaol, serving six months with hard labour. He was released in the late summer of 1891.

Perhaps, as he subsequently claimed, he spent the next few years in the army. That might explain why, during that period, no further entries appeared on the police record sheet headed “SMITH, George Joseph.” On the other hand, he may have been more discreet in his criminal activities—or simply fortunate not to be caught. Another possibility is that his transgressions were recorded on record sheets bearing names other than his own: distinctly likely, this, for when he was arrested for his final, dreadful offences, the list of his aliases looked not unlike an electoral roll for a small town.

He was “George Baker” when, in July 1896, he was sentenced to a year in prison for three cases of larceny and receiving. The fact does not appear to have been included in the evidence against him, but by now he had latched on to the idea of using members of the fair sex unfairly: he had persuaded a domestic servant to become a job-hopper, misappropriating her employers’ property shortly before each hop.

The following year, once he was free, he moved to the Midlands town of Leicester. As a sort of “in-joke,” so esoteric that he allowed no one else to appreciate it, he called himself “Love.” Caroline Thornhill, a teenaged native of the lacemaking town, fell under the spell of “Love”—but not to the extent of accepting his suggestion that they should live in sin. So in January 1898, when he was just twenty-six, he married Caroline. The wedding was a quiet affair, for the bride’s relatives so disapproved of “George Love” that they boycotted the ceremony.

The relatives were soon able to remind Caroline that they “had told her so.” Within six months, life with “Love” became intolerable, and Caroline sought refuge with a cousin in Nottingham. But her husband pursued her; and persuaded her to accompany him south, where—first in London, then farther south, in the seaside towns of Brighton, Hove, and Hastings—he wrote references, posing as her last employer, which helped her to obtain domestic posts. Perhaps needless to say, each house in which she worked was less well stocked with trinkets by the time she moved on to the next position George had chosen for her. The crooks’ tour ended when the Hastings police arrested “Mrs. Love.” Smith managed to evade capture. He travelled to London, booked into a boarding house, and, rather than fork out money for his digs, “married” the landlady at a register office near Buckingham Palace. That was in 1899.

About a year later, Caroline chanced to spot Smith window-shopping in Oxford Street. She informed a constable. As her husband was led away, she called after him, “Treacle is sweet—but revenge is sweeter.” Found guilty of receiving stolen goods, Smith was sentenced to two years’ imprisonment.

Upon his release, he stayed a few days with the landlady-“wife,” then set off for Leicester to find Caroline—whether in the hope of making things up or with the intention of harming her, one cannot be sure. Either way, it was a choice of evils for Caroline. Luckily for her, she had some loving and brawny brothers, who chased “Mr. Love” out of town. But by now Caroline was a bundle of nerves. Deciding that she needed to get far away as fast as possible, she boarded a ship to Canada.

Thirteen years passed before she was summoned back to England to identify as her legal husband the man who had illegally married a number of other women, latterly for the purpose of acquiring a quick profit from a self-imposed state of widowerhood. Caroline was unfortunate in being George Joseph Smith’s first, and only real, wife—but she could console herself with the thought that at least the marriage had lasted.

I am not making an original observation but am merely passing on a remark made by others when I say that, exceptional to the law of averages, a number of mass-murderers have ostensibly earned their living from trade in secondhand goods.

Of course, this raises an egg-and-hen question: which came first? Did the need for used items, as stock or to satisfy the stated requirements of customers, cause the dealers to turn to crime—or did these men, criminals first, drift into the trade, perhaps seeing it as a means of reducing their reliance on “fences” for the disposal of loot? Sadly for criminologists who like neat, cut-and-dried findings (and who have been known to fashion them by ignoring details that don’t conform), some dealers become criminals … and some criminals become dealers.

George Joseph Smith took the latter course. It seems that he started dealing, travelling the country in search of both secondhand wares to buy (or, better, pilfer) and people to buy them, soon after his release from prison in October 1902.

As a profitable sideline to the trade in used goods, he preyed on unused women—virginal spinsters who, with a little flattery, a few promises, a taste of what they had been missing, could be induced to part with a dowry that would lift them off the shelf. As soon as the fleecing was accomplished, Smith made himself scarce. He enjoyed this work, finding in it a mixture of business and pleasure—the pleasure being twofold, derived partly from the satisfaction to his ego of a playacting job well done, and partly from what was then referred to as “gratification of strong animal propensities.”

Not all of his victims were spinsters. To amend a line of a then-popular song: oh, he did like to be beside the seaside. Many of his exploits occurred in coastal resorts. In June 1908, when he was in Brighton (one of the towns on the south coast where, nine years before, he had forced his wife Caroline to filch), he struck up a conversation with a widow whom he “just happened to encounter” on the promenade. Mrs. F. W. (her name was never revealed) told Smith that she was in Brighton only for the day and that she lived and worked at Worthing, a few miles along the coast. Unfortunately for Mrs. F. W., she also gave Smith her address.

The very next day, she received a “gentleman caller.” Yes, it was Smith—who, unusually, was using his real name. While Mrs. F. W. was still recovering from the shock of seeing him again, he shocked her still more—most pleasurably—by blurting out his belief that the meeting on the front at Brighton had been engineered by Kismet, with some assistance from Cupid, and that, if she did not find him utterly repulsive, she must accept Destiny’s word for the fact that she should become his nearest and dearest. Delightedly flabbergasted, the widow murmured something about the need for a period of courtship. But—ever so politely—Smith noted the silver threads among the gold of her hair, said that they ought not to waste a single precious moment, and, his masterfulness making Mrs. F. W. reach for the sal volatile, enquired if she had made any engagements for a date three weeks hence that were more pressing than the register-office wedding he had in mind.

Oh my, such a rush of words. Such a rush that Mrs. F. W. treated Smith’s question about her worldly goods as an unimportant aside. Having agreed to plight her troth, she introduced George (yes, they were on first-name terms by now) to her best friend—who took an instant and violent dislike to him. Ascribing the friend’s reaction to sour grapes, Mrs. F. W. travelled with Smith to London. Such a kind man, he insisted on carrying all her baggage; far from complaining of the weight, he fretted that she might have left something of value behind.

In London, they shared an apartment (maybe very properly, maybe with some premarital hanky-panky—Mrs. F. W. did not subsequently divulge the sleeping arrangements). The widow was taken on two outings in the metropolis. First, to the north of the city, where Smith insisted on showing her round an interesting new post office—and, while they were there, persuaded her to withdraw her savings—and to give the cash to him for safe keeping. Second, to the western outskirts, where Smith treated her to an evening of greyhound racing—and after telling her that he would only be gone a minute, dashed back to the apartment. By the time she got there, not only was there no sign of Smith but there was an entire absence of her belongings.

With money realized from these, together with the widow’s savings, Smith opened a secondhand furniture shop in the West Country city of Bristol. In a house just a few doors along the road, a young woman named Edith Pegler lived with her mother. Learning that she was seeking a job, Smith asked her to be his housekeeper. Edith soon discovered that her new employer could not afford to pay her wages; but even sooner than that, she was under his spell.

They were married—Smith for the umpteenth bigamous time—on 30 July 1908. I give the exact date only to illustrate the speed of Smith’s romantic conquests, the brevity of the period between his first meeting with a woman and, if he felt that the journey to a register office was really necessary, the wedding ceremony: Mrs. F. W.’s withdrawal of her savings from the North London post office was effected on 3 July, less than four weeks before Edith Pegler became—or thought she had become—Mrs. Smith.

“Mrs. Smith” is correct: at the Bristol register office, Smith was for the first time “married” under his real name—perhaps because, for once in his life, he felt a slight affection toward a woman. Edith was less cruelly treated than were the rest of his dupes. Aside from the fact that Smith actually provided her with a trousseau (he didn’t let on to Edith that it had come from the bottom drawer of a young skivvy he had fleeced in the seaside town of Bournemouth), he never, not once, used her as a criminal accomplice; so far as she knew, when for long stretches he was away from home, he was “about the country dealing.” In the year following the wedding, while doing some deals in Southampton—another coastal town, notice—he met and went through a form of marriage with a girl who was quite nicely off. After a honeymoon of a few hours, he left her penniless.

His next port of call was the Essex seaside town of Southend, where he invested most of the Southampton girl’s money in a house. The transaction completed, he returned to Bristol.

One day during the summer of 1910, while he was sauntering in Clifton, on the western outskirts of Bristol, his predatory gaze fell upon a girl named Bessie Mundy.

She was destined to be his first murder victim. Or the first so far as is known.

A slim, plain-featured spinster, Bessie Mundy was thirty-three: five years younger than the man with the icicle-blue eyes who introduced himself as Henry Williams when she was out walking near her home in Clifton. Her father, a bank manager, had died a year or so before, leaving her well provided for; she had £2,500 in gilt-edged securities—the equivalent of some £75,000 ($120,000) today.

That made her irresistibly attractive to Smith. He wooed her, won her, and wedded her (or so she thought; she was not to know that the ceremony at Weymouth registry office did not legitimize the relationship, for the simple reason that Smith, not yet a widower, never divorced, had gone through the same ceremony any number of times before).

On the very wedding day, 26 August 1910, Smith wrote to Bessie’s solicitor, requesting a copy of her late father’s will. When this turned up, Smith may have muttered a few rude words, because the document showed that the bequest to Bessie was protected; she received an income of a mere £8 a month. Still, he was slightly cheered to learn that the solicitor held £130-odd to cover emergencies. So far as Smith was concerned, an emergency had just arisen: he inveigled the liquid funds from the solicitor.

Not content with these, he rifled Bessie’s handbag before absconding. The next morning, she received a letter—bearing no return address, of course—that began,

Dearest, I fear you have blighted all my bright hopes of a happy future. I have caught from you a disease which is called the bad disorder. For you to be in such a state proves you could not have kept yourself morally clean. … Now for the sake of my health and honour and yours too I must go to London and act entirely under the doctor’s advice to get properly cured of the disease.

In fact, Smith took a train to Bristol, not London, and there rejoined Edith Pegler. He did not stay in Bristol long, but, with the faithful Edith in tow, went on a circular tour, wheeling and dealing as he travelled, returning to Bristol toward the end of 1911.

After seven weeks—reasonably happy ones for Edith, despite Smith’s frugality with housekeeping money—his wanderlust took him away again. Though Edith was left virtually penniless, she somehow managed to survive on her own for five months; then she returned to her mother.

In March 1912, Smith’s travels took him to the Somerset coastal resort of Weston-super-Mare. By a dreadful coincidence, Bessie Mundy was staying at a boardinghouse in the town. One morning, she went out to buy some flowers as a gift for the landlady, Mrs. Sarah Tuckett, who was also a family friend. As she walked along the front, she saw Smith (or Henry Williams, as she knew him) staring at the sea.

Certain criminologists subscribe to the theory of “victimology”—a belief that, in many cases, particularly of murder, the victim is more or less responsible for his or her own plight. I can think of no person who more blatantly supports the theory than Bessie Mundy. Considering how Smith had deceived her, robbed her, divested her of self-esteem, and, adding acid to the lemon, accused her of infecting him with a venereal disease, one would suppose that she had but two choices when she saw him—to rush back to the sanctuary of the boarding house or to report her sighting to the police.

But no; she did neither of those things. Incredibly, what she did was to approach Smith, timidly cough to announce her presence, and, once he had recognized her, ask how he was keeping. The moth, wings seared by fire, had returned to the flame.

Mrs. Tuckett received a bunch of daffodils—not from her excited guest but from Bessie’s “long-lost husband.” The flowers did not help to dispel the landlady’s dislike or suspicion of Smith. When he said that he had been scouring the country for his dear Bessie for over a year, Mrs. Tuckett enquired why he had not got in touch with her relatives, whose addresses he knew, or with her solicitor. There was no answer to that. Mrs. Tuckett told Smith that she intended to send a wire to one of Bessie’s aunts. He left Weston-super-Mare that night. And Bessie, who earlier had informed the landlady that she had “forgiven the past,” went with him.

The reunited couple travelled around, staying in lodgings, until late in May 1912, when they turned up at Herne Bay, Kent, and rented a house, No. 80 in the High Street, for thirty shillings a month.

They had been in the town for only a few days when Smith consulted a local solicitor about Bessie’s “protected” £2,500. Was the protection absolute? What if Bessie were to make a will in his favour? Would all her money be his if she died?

The solicitor received counsel’s opinion on 2 July.

It was Bessie Mundy’s death warrant.

Less than a week later, she and Smith made mutual wills.

Next day, Smith went into an ironmonger’s shop, and after some haggling, agreed to buy a £2 bath for £1.17s.6d. Though he didn’t pay for the bath on the spot, the ironmonger agreed to deliver it that afternoon.

Smith’s purchase would have surprised Edith Pegler, for in all the time she had lived with him, he had only taken a bath once, perhaps twice. And he had advised her, “I would not have much to do with baths if I were you, as they are dangerous things. It has often been known for women to lose their lives in them, through having fits and weak hearts.”

One wonders how Bessie viewed the acquisition. Perhaps, poor creature, she thought back to the letter that had accused her of transmitting a venereal disease, in which a line following those I have quoted said that she had either “had connections with another man … or not kept [herself] clean.” Maybe she inferred that Smith, concerned at the insufficiency of her personal hygiene but no longer wishing to offend her, had bought the bath as a tacit hint. Did she vow to herself that she would plunge into the bath morning, noon, and night, scouring her meagre body of all perhaps contagious impurities?

There is no way of answering such questions. Bessie herself was the only person who could have said what went through her mind. But she was alone, friendless, far from anyone in whom she might confide; Smith had seen to that. In any case, she had precious little time left in which to speak of matters involving her husband; to speak of anything.

After the arrival of the bath, Smith was as busy as a bee in creating the impression that he feared for the life of his beloved Bessie.

The ironmonger delivered the bath during the afternoon of Tuesday, 9 July. Next morning, Smith took Bessie to see Dr. Frank French—who, as it happened, was the least-experienced medical practitioner in the town. Smith said that his wife had had a fit. The young doctor may have wondered whether Bessie was suffering from amnesia as well as epilepsy, for she did not remember having a fit. French prescribed a general sedative.

Two days later, Smith called the doctor to the house. Bessie was in bed—unnecessarily, it seemed to French, who could see nothing wrong with her. Still, just to be on the safe side, he went back to the house later in the day. Bessie looked “in perfect health.” And she felt fine, she told the doctor—just a touch of tiredness, but that was probably because of the heat wave.

The touch of tiredness must have evaporated soon after the doctor’s departure, for she then wrote a letter to an uncle in the West Country. The letter, which went off by registered post that evening, spoke of two “bad fits,” and continued,

My husband has been extremely kind and done all he could for me. He has provided me with the attention of the best medical men. … I do not like to worry you with this, but my husband has strictly advised me to let all my relatives know and tell them of my breakdown. I have made out my will and have left all I have to my husband. That is only natural, as I love my husband.

At eight o’clock next morning—Saturday, 13 July—Dr. French received a note: “Can you come at once? I am afraid my wife is dead.”

As soon as the doctor arrived at the house, Smith ushered him upstairs. Bessie was lying on her back in the bath, her head beneath the soapy water. Her face was congested with blood. French lifted the body from the bath and, simply because he thought it might be expected of him, went through the motions of applying artificial respiration, with Smith assisting by holding the dead woman’s tongue.

An hour or so later, a coroner’s officer took a statement from Smith, and in the afternoon a neighbour, Ellen Millgate, came to the house to lay out the body. Though she was practised at the task, this was the first time that she had found a corpse lying naked and uncovered on bare boards behind a door. Odd, she thought.

Just as odd, when one comes to think of it, was the fact that the doctor had found the body still submerged, the face staring up as if through a glass darkly. Surely the natural thing for Smith to have done when he first entered the room was to lift his wife, or at least raise her head, from the water.

But neither of these oddities, nor any of the several others, perplexed the coroner or his jury, whose verdict was relayed to Bessie’s relatives in a note written by Smith on the Monday, soon after the proceedings: “The result of the inquest was misadventure by a fit in the bath. The burial takes place tomorrow at 2 P.M. I am naturally too sad to write more today.” Until they received this note, the relatives were not even aware that an inquest had been held. And there was no time for them to travel from Bristol to Herne Bay to attend the funeral (which Smith arranged “to be moderately carried out at an expense of seven guineas,” the body being interred in a common grave).

Within forty-eight hours of the funeral, Smith sold most of the furniture in the house, returned the bath (which he had not paid for) to the ironmonger, and, most important, instructed the solicitor who only nine days before had drawn up Bessie’s will to obtain probate.

By the middle of September, Smith was better off by about £2,500 (in present-day terms, about £100,000–$160,000). He was then back in Bristol, again living with Edith Pegler. It appears that, no more than a month or so after his return from Herne Bay, Smith came close to letting Edith in on the secret of how he made money from matrimony: he enlisted her aid in arranging insurance on the life of a young governess, but then for some reason decided not to go ahead with whatever scheme he had in mind.

If that scheme had been carried through, requiring him to remain in Bristol, he might never have met Alice Burnham; and she, a twenty-five-year-old nurse, rosy-cheeked and ample-bosomed, would probably have attained the age of twenty-six.

Smith first encountered Alice in Southsea on a late-summer day in 1913. Having quizzed her about her financial situation, he proposed marriage and was delightedly accepted. Whereas he had gone out of his way to avoid meeting relatives of his earlier victims, he insisted on visiting Alice’s father, a fruit-grower living at Aston Clinton, Buckinghamshire, northwest of London. His insistence was entirely due to the fact that Charles Burnham was looking after £100 of his daughter’s money. The visit, at the end of October, was not a success. Contrary to Alice’s starry-eyed, rose-coloured view of her beau, Mr. Burnham considered Smith a man of “very evil appearance—a bad man.”

But Alice, ignoring her father’s fear that “something serious would happen” if she went ahead with the marriage, became “Mrs. Smith” (yes, George was using his real name this time) on 4 November. The day before, her life had been insured for £500.

Owing to some irritating holdups (to do with the nest egg Alice had left with her father, the life insurance, and the making of her will), Smith had to wait over a month before he could become a widower again. Choosing Blackpool as the scene of his crime, on Thursday, 10 December, he knocked at the door of 25 Adelaide Street, a guesthouse run by Mrs. Susannah Marsden, and, while Alice loitered by the luggage, asked the landlady if there was a bath in the house. As the answer was no, Smith enquired whether Mrs. Marsden knew of a nearby establishment offering bed, board, and bath.

On Mrs. Marsden’s recommendation, the couple took lodgings at 16 Regent’s Road, where the landlady was Mrs. Margaret Crossley. As soon as they had unpacked their bags, they walked to Dr. George Billing’s surgery at 121 Church Street. Smith, who did all the talking, explained that his wife had a nasty headache. The doctor gave Alice a pretty thorough examination, found nothing wrong, prescribed tablets for the headache and a powder to clear the bowels, and requested a fee of three shillings and sixpence—which Smith, would you believe, paid at once, without haggling.

It may be that Mrs. Crossley was willing to make allowance for the transgressions of out-of-season boarders, for at about eight o’clock the following night, Friday, when she saw water pouring down a wall in her kitchen, she did not rush upstairs to complain about the overfull bath. Five or ten minutes later, however, she was summoned upstairs by Smith, who said that he could not get his wife to speak to him. The reason for Alice’s taciturnity was that her head was submerged in soapy water.

In many respects, the events that followed were reproductions of those following Bessie Mundy’s abrupt demise. Dr. Billing was called; he, in turn, called the coroner’s officer; on the Monday, an inquest jury took just half an hour to return a verdict of accidental death. Smith negotiated a cheap funeral, took the first steps toward collecting his bequest and the payment from the insurance society, and left the town.

Just before his departure, he reluctantly gave Mrs. Crossley part of what he owed her and handed her a card on which he had written a forwarding address in Southsea. The landlady scribbled on the back of the card: “Wife died in bath. I shall see him again some day.” She was right.

How many women did George Joseph Smith marry? And how many did he murder?

One cannot give a sure answer to either question. Certain of his exploits are well documented; but it is quite possible that he committed crimes that were never ascribed to him. For one thing, he was such a busy rogue that even if he could have been persuaded to tell the truth, the whole truth, and nothing but the truth, some of his matrimonial misdeeds might have slipped his mind; for another, some of his female dupes who remained extant may have decided that discretion was the better part of valour; and for yet another, when he was at last brought to book, some of his victims, or their surviving relatives or friends, may not have connected him with the man they had known under an alias other than those listed in press reports—Love … Williams … Baker … James … and so on.

“Charles Oliver James” was the name he was using in the late summer of 1914, when, all within a fortnight, he met, “married” and left impoverished a young domestic servant called Alice Reavil.

A month or so later, he was “John Lloyd.” That was the name he gave when introducing himself to Margaret Lofty, a thirty-eight-year-old spinster with pouting lips and dark hair that she arranged in kiss curls over her negligible forehead. The daughter of a parson, she eked out a meagre existence as a companion to elderly women residing in tranquil cathedral cities. Sadly appropriate to her fate, it was in Bath that she first encountered Smith.

As her savings of £19 were ludicrously inadequate to Smith’s purpose in marrying her, he added to his proposal instructions regarding life insurance. Once the first—and, as it turned out, only—premium was paid, he married Margaret at a register office. The date was 17 December, a Thursday—almost exactly a year after the death of Alice Burnham; two and a half years since the death of Bessie Mundy.

That evening, after Smith had been refused lodgings at one house in North London (because the landlady was frightened by his “evil appearance”), he took a room for himself and his bride at 14 Bismarck Road, Highgate, having first ascertained that there was a bath in the house.

The grim routine began. Before unpacking, Smith took Margaret to see a Dr. Bates and told him that his wife was suffering from a bad headache. It seemed to the doctor that she was terrified to speak. Next morning, the couple visited a solicitor for the making of Margaret’s will, then went to a post office to withdraw the balance in her savings account.

In the evening, just after eight o’clock, Louisa Blatch, the landlady, was doing some ironing in her kitchen. She heard “a sound of splashing—then there was a noise as of someone putting wet hands or arms on the side of the bath … then a sigh.”

His mission accomplished, Smith crept down the stairs. He entered the parlour, seated himself at the harmonium, and began to play “Nearer My God to Thee.”

After the short recital, Smith wandered into the kitchen to ask Mrs. Blatch if she had seen anything of his wife. He then went upstairs, “found” Margaret lying dead in the bath, and shouted to the landlady for help.

Subsequent events were almost carbon copies of those that had followed the drownings in Herne Bay and Blackpool. But there was one important addition: the inquest, with its verdict of accidental death, was reported in the News of the World Sunday paper under the double headline,

FOUND DEAD IN BATH

BRIDE’S TRAGIC FATE ON DAY AFTER WEDDING?

Though the bereaved husband’s name was given as “Lloyd,” two readers of the report were so struck by similarities between the tragedy in North London and the death of Alice Smith (née Burnham) in Blackpool a year before that they decided to communicate with the police. One of the persons who put two and two together was Joseph Crossley, the husband of the Blackpool landlady; the other was Charles Burnham, the Buckinghamshire fruit-grower whose daughter had drowned in the bath at Mrs. Crossley’s boardinghouse.

Detective Inspector Arthur Neil was put in charge of the investigation. In seeking to untangle the web of Smith’s deceits over a period of some sixteen years, Neil and his helpers made inquiries in forty towns, took statements from 150 witnesses, and traced some of the proceeds of Smith’s crimes to more than twenty bank accounts.

It didn’t take the detectives long to find sufficient evidence to justify Smith’s arrest—but the fact that at the time of his arrest the investigators knew nothing of the death of Bessie Mundy at Herne Bay adds point to Neil’s subsequent observation that there would probably never be a full account of the life and crimes of George Joseph Smith.

At his trial, which was held at the Old Bailey in the summer of 1915, the indictment referred only to the case of Bessie Mundy—who, so far as was known, was the first of Smith’s brides to die a watery death. His fate was sealed when the judge, Mr. Justice Scrutton, allowed the prosecution to introduce evidence relating to the deaths of Alice Burnham and Margaret Lofty, so as to prove his “system” of murder.

Smith was an unruly defendant. He flung abuse at witnesses (describing Mrs. Crossley as a lunatic, Inspector Neil as a scoundrel), and when one of his counsel advised him to be quiet, pounded the rail of the dock with his fist and shouted, “I don’t care what you say!”

He was silent, however, while Bernard Spilsbury, the pathologist, was giving evidence. Before the trial, in seeking answers concerning the method used for the three murders, Spilsbury had enlisted a nurse as a human guinea pig—with near-fatal effect, for when he had suddenly lifted the nurse’s legs so that her head was immersed in bathwater, she had instantly lost consciousness. This experience had convinced Spilsbury that Smith’s trio of victims had died from shock rather than drowning.

Smith did not exercise his right to give evidence on his own behalf—but that does not mean that he remained silent after the case for the Crown had been presented. He muttered and moaned during the closing speeches and often interrupted the judge’s summing-up, claiming at one point, “I am not a murderer—though I may be a bit peculiar.”

The jury was out for only twenty minutes. After stating that he thoroughly agreed with the verdict of “guilty,” the judge told Smith that he would spare him the usual exhortation to repent: it would be a waste of time.

The sentence of death was carried out on 13 August, a Friday. Before he was hanged, Smith asserted, with evident conviction, “I shall soon be in the presence of God”—a prophecy that, for God’s sake, one trusts was over-optimistic.

Writing in the Daily Telegraph recently, Sir Ludovic Kennedy, who in the past has pronounced on what constitutes worthwhile evidence and what doesn’t, came up with another pronouncement. Having said that the first things he wants to see before deciding whether or not to look into any alleged miscarriage of justice in a murder case are post-sentence letters from the convicted person, he explains his reason for that primary consideration: if anyone found guilty of murder continues to insist, in sincere-sounding prose, that he is not guilty, then it is painfully obvious that he must be innocent.

So as to keep my blood pressure in check, I managed, though it took some doing, to forget Kennedy’s pronouncement—till a day or so ago, when I came across some letters from a Mr. George Smith that were published in the correspondence columns of the Bath & Wiltshire Chronicle toward the end of 1911.

Mr. George Smith—who, he? Well, before telling you, let me quote from three of the four letters, leaving out one that must have put the fear of God into hypochondriacal residents of Twerton, on the southern outskirts of Bath, for it raised the spectre of a multidisease plague thereabouts, all because the local council had reduced the frequency of refuse collections from that village.

The other letters deal with extra-Twertonial issues. Passages in them bring on a feeling of déjà vu: their tone and content have been echoed over the years and still are, thereby making Mr. Smith seem both ancient and modern.

The first of the letters reads, in part, “If the new system of education be far more serviceable and substantial than it was 20 years ago, how is it that we do not see the fruits in the general behaviour of children? Can any grown-up person deny the fact that when they themselves were children, their obedience to parents and superiors was more observed than it is today? Take, as another instance, the coarse manner, the lack of true brotherly and sisterly feeling, and the late hours indulged in by children. Then there is the vast amount of objectionable literature, such as the ‘penny dreadfuls,’ read by children. In conclusion, the training of children is undoubtedly a great problem, and cannot be solved by the State alone. Thus it becomes the duty of parents to do their share, in as much as there are two educations—the one which is taught at school, and the other which comes from parents, the latter being as important as the former.”

In December, Mr. Smith launched a further attack upon penny dreadfuls and more expensive “objectionable publications”: “I maintain that they are doing more harm and are accountable for more law-breaking than excessive drinking, and that unless our shops are cleansed from such a living curse—and the young prevented from obtaining such poison—our new generation, instead of rising to credit us, will only live to disgrace us.”

Between those two letters, Mr. Smith had his say on the subject of reformation of criminals: “It is impossible to purify any sphere of society while the hardened unreformed criminal is in our midst. Yet the public, as a whole, seldom, if ever, turns its attention toward this down-fallen class, never troubling as to what system the authorities are using in order to reform, as well as punish, these unfortunate beings. It is only when the public is reminded from time to time by the astounding revelations made known through the Press by some of the more intellectual of discharged prisoners that any regard is paid in that direction, and the whole matter, unfortunately, soon falls into oblivion.”

A clue to the identity of Mr. Smith: a private letter, written by him some two years after the published ones, replying to a request for information about his antecedents from Mr. Charles Burnham, who had just heard that his daughter Alice had suddenly and surreptitiously become Mrs. George Smith: “My mother was a Buss horse, my father a Cab-driver, my sister a roughrider over the Arctic regions—my brothers were all gallant sailors on a steam-roller. This is the only information I can give to those who are not entitled to ask such questions.”

That letter was written by George Joseph Smith, the so-called brides-in-the-bath murderer. And so were the published ones “painfully obviously” penned by a concerned citizen, a conscientious churchgoer, a pillar of the community. The address on those letters—91 Ashley Down Road, Bristol—was George Joseph’s. Though it was his permanent home, tended by his only permanent “wife,” Edith Pegler, he was more often than not away from it, travelling the country as a dealer in secondhand merchandise, meanwhile pursuing the far more profitable sideline of snaring shelved spinsters, “marrying” them, and ditching them the moment he had appropriated their assets. His career as a ubiquitous bigamist seems to have begun at the turn of the century, when, still in his twenties, he had served three terms of hard labour for larceny and receiving.

Shortly before his flurry of Letters to the Editor, he had “married,” fleeced, and deserted Bessie Mundy; three months after writing the last of those letters, he would, quite by chance, meet her again, easily persuade her to forgive and forget, also to sign a will, then buy a bath and drown her in it. The same ostensibly accidental fate befell Alice Burnham; likewise in 1914, Margaret Lofty. But the third sudden death turned out to be one drowning too many; it was compared to the earlier bath-night tragedies, to decide that the evidence of Smith’s system was overwhelming.

In sincere-sounding love letters to Edith Pegler, he insisted that he was a victim—of “perjury, spite, malice, vindictiveness.” On the morning of Friday, 13 August 1915, minutes before (to quote his own words in a different context) he fell into oblivion, he stated, “I shall soon be in the presence of God—and I declare before him that I am innocent.”

Oh, sure. Of course, no one (but Sir Ludovic Kennedy) can doubt that Smith’s protestations were untrue. He appears to have placed undue reliance upon a version of the drama-school maxim: “Success as an actor is all down to sincerity—so if you can fake sincerity, you’ve got it made.”

1. Now called Waterlow Road. During the Great War, all Bismarck-entitled thoroughfares in the capital patriotically were renamed.