The Lindbergh case has been turned into a sort of fiction.

That has been achieved mainly through the efforts of certain authors of books about the case, makers of television programmes about it, writers of plays said to be based upon it, and a woman who for nearly sixty years did her utmost to make people disbelieve the truths of the case. Early in 1993, the fiction was strengthened when, in an episode of a no-expense-spared BBC television series, Fame in the Twentieth Century, the presenter, the very Australian writer Clive James, told millions of viewers that the man executed for the kidnapping and murder of the Lindbergh baby “was almost certainly innocent.”

Mr. James’s reference to the case was a postscript to comments on the immense fame of Colonel Charles A. Lindbergh, all because he had made the first solo airplane flight across the Atlantic. That was in May 1927. Two years later, the “secret” marriage of Lindbergh, the Lone Eagle, to Anne Morrow, a daughter of a rich politician, was given front-and-subsequent-pages coverage throughout the world. And so was the birth of their son, Charles Jr., in June 1930. Long before the arrival—the “perfect landing”—of the “Eaglet,” Lindbergh had grown tired of being a public show. Seeking a refuge from fame, he bought a wooded estate a few miles from the small town of Hopewell, in the desolate Sourland region of New Jersey, and had a two-storeyed house built, to his precise specifications, in a clearing at the end of a long curving driveway from the road. Believing the publicity that he had come to despise, which made him out to be everyone’s hero, and therefore inviolable, he did not consider the fact that so secluded a residence was ideally suited as the setting for a crime.

Apart from some finishing touches—including replacement of a shutter on one of the nursery windows, which had warped, making it impossible to fasten—the house was complete by March 1932. The Lindberghs had taken to spending long weekends there, the rest of the time at the Morrows’ home at Englewood, fifty miles or so to the northeast, looking across the Hudson River to the Bronx, the northernmost borough of New York City. But that routine was broken on Tuesday, 1 March: as it was a miserable, blustery day, and the baby, now twenty months old, was suffering from a chill, Mrs. Lindbergh decided to remain at the new house. Lindbergh, who spent part of the day in New York City, drove back in the evening, arriving at half past eight; on his way through the servants’ quarters, he paused to ask Betty Gow, the Scottish-born nanny, about his son’s slight illness. The other servants, butler and cook, were a married couple, Oliver and Elsie Whateley, who were both from England.

At about ten past nine, soon after the Lindberghs finished dinner and went into the living room, they heard a noise—sounding to Lindbergh “like the slats of an orange-box falling off a chair.” Supposing that the noise had come from the kitchen, they resumed the conversation that it had briefly interrupted.

At ten o’clock, Betty Gow went to the nursery to check that the baby was still sleeping as soundly as when she had left him two hours before, swaddled against the merest draught with a sleeping suit, a woollen shirt, and a sleeveless garment she had sewn together earlier in the evening with distinctive blue thread that she had got from Mrs. Whateley: “a proper little flannel shirt to put on next his skin.” Leaving the door open so as to give some light from the landing, she groped her way to the crib. The baby was not there. Betty Gow felt no alarm, for she assumed that Mrs. Lindbergh, perhaps hearing the child crying, had taken him from the crib. She went to Mrs. Lindbergh’s room, found her on her own, and, fearful now, ran in search of Lindbergh, hoping against hope to see him holding his son—and, finding him in the library, alone, screamed to him to follow her back to the nursery. They searched the room, then every other part of the house, now with Mrs. Lindbergh and the Whateleys helping—and then Lindbergh shouted to the butler to phone the police, grabbed a hunting rifle, and ran through the front door, around the clearing, and along the driveway to the road.

He had returned, had gone back to the nursery, before the first policemen arrived: the entire force of Hopewell, numbering two. He pointed to an open window, the one with the warped shutter, and to a white envelope on the muddied sill, saying that he had not touched it in case it bore the kidnapper’s fingerprints. When the envelope was eventually opened, having been dusted without result, it was found to contain a single sheet of white paper, also free of prints, on which a message was written in blue ink:

Dear Sir

Have 50000$ ready 25000$ in 20$ bills 15000 in 10$ bills and 10000 in 5$ bills. After 2–4 days we will inform you were to deliver the mony We warn you for making anyding public or for notify the police. The child is in gut care. Instruction [or “indication”] for the letters are singnature

The “singnature” was of two interlocking circles, with three holes near the perimeters.

Lindbergh and the local policemen went outside. Shining their torches on the muddy ground below the open window, they saw two indentations made by the ends of a ladder. The ladder itself was lying some twenty yards away. Obviously homemade, it was of three sections, each seven feet long. The two lower sections were connected (with dowel pins pressed through matching holes in the rails), and the top section, which the kidnapper had not needed so as to reach the window, was nearby. There were splits in the rails of the connected sections, almost certainly caused during the kidnapper’s descent with a burden weighing thirty pounds, making a combined weight that overstrained the timber, particularly where the sections were held together with the dowel pins. Again almost certainly, the noise the Lindberghs had heard at about ten past nine was the splitting of the ladder rails.

By midnight, the investigation was being carried out by officers of the New Jersey State Police, directly led by Colonel H. Norman Schwarzkopf, who had been in charge of the semimilitary force since its formation eleven years before. (In the Gulf War of 1991, the Allied forces were commanded by his son, General Norman Schwarzkopf.) By daybreak, there were more state policemen at Hopewell than in the rest of New Jersey put together. Even so, they were outnumbered by reporters and cameramen, who were themselves outnumbered by sightseers. The early stages of the investigation, the most important ones, were a complete shambles. It has been said that Schwarzkopf and his aides “suffered, under the sudden spotlight, from a bad attack of stage-fright,” but the truth of the matter is that the spotlight showed them up as incompetent detectives. None of them thought to measure, let alone make a plaster cast, of a footprint, probably the kidnapper’s, below the nursery window; the inspection of the nursery was superficial; dozens of people, not only policemen, were allowed to handle the ladder although it had not been thoroughly tested for fingerprints.

Three days after the crime, Lindbergh received, by post from Brooklyn, a second note from the kidnapper, repeating the warning against involving the police, saying that the baby was in “gut health” and raising the ransom demand to $70,000. The following day, another note, similar in tone, was delivered at the Manhattan office of Lindbergh’s legal adviser. Lindbergh issued press statements to the effect that he was eager to negotiate, without bringing in the police. He also announced that, in case the kidnappers (plural, though there were several reasons, including the comparative modesty of the ransom demand, for believing that the crime was the work of an individual) did not wish to deal with him personally, he had authorized two New York bootleggers, Salvy Spitale and Irving Bitz, to act on his behalf. Among many other persons who offered their services as go-betweens were the presidents of Columbia and Princeton universities; Al Capone, whose offer was contingent upon his being given leave of absence from the prison where he had recently begun serving an eleven-year sentence for tax evasion; and John F. Condon, a retired schoolteacher who had lived all of his seventy-two years in the Bronx, which he considered “the most beautiful borough in the world.”

A week after the kidnapping, Condon’s local newspaper, the Home News, printed a letter from him in which he pleaded with the kidnapper to communicate with him, promising both secrecy and the addition of a thousand dollars—“all I can scrape together”—to the ransom money. Next day, he received a letter, containing a sealed enclosure, which said that if he was willing to act as go-between he should “handel incloced letter personally” to Lindbergh and then remain at home every night. He phoned the Lindbergh house, read the letter to the person who answered, and, when told to open the enclosure, read that out as well: explicit instructions regarding the parcelling of the ransom money were followed by the circles-and-holes signature. Condon, asked to come to Hopewell, got a friend to drive him there. Comparison of the letter and the enclosure with the letters that had definitely been written by the kidnapper showed that the handwriting was much the same, there were similar errors of spelling and grammar, and the signatures matched. It was agreed that, in accordance with the kidnapper’s instructions, a small ad should be placed in a New York paper, saying that the money was ready; the message would be signed “Jafsie,” an acronym of Condon’s initials.

Three nights later (Saturday, 12 March), a letter was delivered to Condon by a cabdriver who had received it, together with a dollar for the “fare,” from a man who had flagged him down a short distance away. Following the instructions in the letter, Condon went to a deserted frankfurter stand, where he found a note directing him to Woodlawn Cemetery, in the Bronx. After wandering around there for some minutes, he was approached by a man who, speaking with a strong Germanic accent, said that he was one of a gang of five kidnappers, two of whom were women. Condon and the man, who called himself John, talked for over an hour, meanwhile moving from place to place in and near the cemetery. The man said that the baby was alive and well, receiving constant care aboard a boat. Just before he hurried off into the cover of woodland, he promised to send Condon “a token” that would prove beyond doubt that he was not a hoaxer.

The token—the baby’s sleeping suit, parcelled and sent by post—was delivered to Condon on 15 March. The negotiations continued, with Jafsie ads bringing replies through the post—till Saturday, 2 April, when final arrangements were made for payment of the ransom. The serial numbers of the bills had been taken; at Condon’s suggestion, the money was in two packets, one of $50,000, the original asking price, and the other of $20,000. That night, Condon, in a car driven by Lindbergh, followed a trail of messages, at last to a dirt road beside St Raymond’s Cemetery, where “John” was waiting. Lindbergh heard him calling out to Condon to follow him into the cemetery. After some argument, the kidnapper agreed to accept the $50,000, and handed Condon a “receipt” which, so he said, gave instructions for finding the baby. He ran off into the cemetery, and Condon returned to where Lindbergh was waiting. The note read:

The boy is on the boad [boat] Nelly. It is a small boad 28 feet long. Two persons are on the boad. The [they] are innosent [sic]. You will find the boad between Horseneck Beach and Gay Head near Elizabeth Island.

Early next morning, Lindbergh began flying over that area, off the coast of Massachusetts. He continued the search till late on the following day, long after he had accepted that the “boad Nelly” was a figment of the kidnapper’s imagination.

On Thursday, 12 May, while Lindbergh was searching for another “kidnap boat” (the invention of a man named John Hughes Curtis, whose motive for concocting the complicated hoax remains obscure), the decomposed body of a baby boy was found, quite by chance, lying facedown in a thicket beside a little-used road five miles from the Lindbergh home. Any slight doubt as to whether the body was that of the kidnapped child was dispelled by Lindbergh, who, returning in response to a radio message, viewed the body in a mortuary and recognized several physical characteristics, particularly a malformation of the bones in one foot; also by Betty Gow, who identified garments, one of which was the flannel shirt which she had stitched together with unusual blue thread. According to the local coroner, the principal cause of death was “fractured skull due to external violence.”

At last released from constraints imposed by the possibility that the baby was still alive, law officers, not only of New Jersey, set about tracing the man who had committed the double crime against “the first family of America.” Not that there was much to go on. The best hope seemed to be that the criminal would be caught through his spending of the ransom money. The list of the serial numbers was circulated to banks, and cashiers were given an incentive to watch out for the bills by the offer of a reward of seven dollars, partly contributed by Lindbergh, for the spotting of any of them. They soon started to appear, usually in deposits made by shops, cafes, and filling stations; depositors were interviewed in the hope that they could connect the particular bills with specific transactions and recall something about the customer. As each bill, or batch of bills, was spotted, the location of the place where it had turned up was marked on a map, which soon showed a preponderance of transactions in the Bronx and the contiguous northern part of Manhattan.

Part of the ransom money was in gold notes, and in May 1933, following President Roosevelt’s order that all such notes were to be exchanged for ordinary currency at a Federal Reserve Bank, someone signing himself J. J. Faulkner exchanged nearly three thousand dollars’ worth of them at the bank in New York City; soon after it was noticed that they came from the ransom (they constituted the largest transaction ever spotted), it was found that no one named Faulkner lived at the address given by the exchanger, whom the cashier could not describe at all.

Later in the year, the police sought help from attendants at filling stations, saying that whenever a customer paid with a bill of ten or twenty dollars, the attendant should write the licence number of the customer’s vehicle on the bill. That initiative would produce the vital break in the case.

While the “Lindbergh squads” of detectives doggedly stuck at their respective tasks—each acting virtually independently, and some of them as if in competition rather than cooperation with the others—a most unconventional detective was at work.

His name was Arthur Koehler. He was a “wood technologist” of the Forest Service of the Department of Agriculture. Shortly after the kidnap case became one of murder as well, he began trying to establish where the criminal had bought the timber to construct the ladder.

Having identified the types of timber, he concentrated on that which was of North Carolina pine. Microscopic examination showed marks made by a particular kind of mechanical plane; the records of manufacturers of such machines revealed that twenty-five were in use; most of those were ruled out because they were used only to dress other types of timber. After months of searching, Koehler found the plane he was looking for at a mill in South Carolina; because a non-standard pulley had been installed in the autumn of 1931, the machine made additional marks that were uniquely the same as those on some of the ladder rails. Koehler visited all of the timber companies to which the mill had shipped ladder-size boards of North Carolina pine during the five months between the pulley-changing and the kidnapping. Only at one of the yards—that of the National Lumber & Millwork Co., in the Bronx—did he find a remnant on which there was an “extraordinary mark,” resulting from the temporary nicking of one of the frequently sharpened blades of the mechanical plane, that he had detected in his examination of the ladder. He was sure that he had found the yard at which most of the timber for the ladder had been bought. Not quite all of it: four apparently old nail holes at one end of the rail he designated as No. 16, as well as the fact that the rail was grubbier than the rest, indicated that the timber was secondhand, that it had been used for some other purpose before becoming part of the ladder; the most likely explanation for the presence of Rail 16 was that the kidnapper, finding that he had not bought quite enough timber, had made up the deficit with an old piece that happened to be nearby. Koehler, whose achievements had set him among the greatest forensic investigators, could do no more—for the time being, that is.

On Tuesday, 18 September 1934, more than two and a half years after the kidnapping, a cashier at a branch of the Corn Exchange Bank in the Bronx spotted a ten-dollar ransom bill in a deposit from the Warner-Quinlan Company, a local filling station. A vehicle licence-plate number—4U-13–14-NY—was written on the margin of the bill. The filling-station manager and his assistant said that the bill had come from a customer driving a blue 1930 Dodge sedan, who had bought five gallons of petrol, costing just under a dollar. The licence bureau provided the name and address of the owner of the car: Bruno Richard Hauptmann, 1279 East 222nd Street, the Bronx. The registration card showed that he was almost thirty-five, of medium build, with blue eyes and “muddy blond” hair, German-born, and a carpenter by trade.

Further inquiries revealed that he was an illegal immigrant (and it was subsequently learned that he had served a five-year prison sentence in Germany for burglaries and a highway robbery—in which he had threatened to kill two women wheeling prams—and that he was wanted by the German police, who considered him “exceptionally sly and clever,” because in 1923 he had escaped from custody while awaiting trial for other burglaries, and fled to America). In 1925, he had married Anna Schoeffler, a waitress, also German-born, who in November 1933 had given birth to a son, named Manfred in homage to Baron Manfred von Richthoven, the German air-ace of the Great War.

At nine o’clock on the morning of the 19th, Hauptmann was arrested after he had backed his car out of the garage in the yard of his house and started driving toward Manhattan. He was searched before being taken to a police station, and a twenty-dollar ransom bill was found folded in his wallet.

Much more of the ransom money—$14,600 of it—was found in various hiding places, including holes burrowed through a block of wood, in his garage. Faintly scribbled in pencil on the inside of a closet door in the house were John F. Condon’s phone number and address; also what appeared to be the serial numbers of banknotes—none corresponding with that of any of the ransom bills.

According to Hauptmann, the ransom money had come into his possession in December 1933—though without his knowledge at that time. He had, he said, agreed to look after a shoebox for a friend and business associate, Isidor Fisch, who was about to take a trip to Germany. Fisch had died during the trip. Hauptmann said that he had forgotten about the box till the summer of 1934, when rainwater had seeped into the closet where he had stowed it; the box, damaged by the water, had been further damaged, to the extent that the contents were revealed, when he had accidentally hit it with a broom. Without saying a word to his wife, he had hidden the bills in the garage. As Fisch had died owing him money, he had felt justified in dipping into the small fortune, unaware that it was criminal loot.

Hauptmann had worked regularly as a carpenter till 2 April 1932, the day when the ransom was paid, but had done only a few odd jobs since; his wife had given up her job as a waitress in December 1932. Their joint earnings since April 1932 amounted to just over a thousand dollars. And yet during that time, though Hauptmann had bought several luxury items, gone on hunting trips, and paid for his wife to visit her relatives in Germany, his capital had risen from just under five thousand dollars to just over forty thousand—including the money in the garage. He attributed his recent affluence to successful dealings in the stock market, but examination of his brokerage accounts showed that he had made a total loss of nearly six thousand dollars. Many of his bank deposits in the same period consisted largely or wholly of coins (two deposits of about four hundred dollars were made up entirely of silver), which suggested to the investigators that he had systematically “laundered” ransom bills by using them for small purchases and getting lots of change. There was nothing to indicate that Isidor Fisch, a small-time dealer in cheap furs, was better off after April 1932 than previously: he had continued to get by without a car, had remained in the cheapest of digs, had borrowed money and tried to borrow more—and apparently would not have been able to afford the trip to Germany from which he did not return if Hauptmann had not stepped in at the last minute with a loan of $2,000.

When Hauptmann was interviewed by the district attorney of the Bronx (with a shorthand writer taking down the questions and answers), he was shown the detached closet door and asked, “Your handwriting is on it?” “Yes, all over it,” he replied. He said that he could not make out some of the notations and could not explain some of the others. Why had he made a note of Condon’s address? “I must have read it in the paper about the story. I was a little bit interest, and keep a little bit record of it, and maybe I was just on the closet and was reading the paper and put down the address. … It is possible that a shelf or two shelves in the closet, and after a while I put new papers always on the closet, and we just got the paper where this case was in and I followed the story, of course, and I put the address on there. … I can’t give you any explanation about the [Condon’s] telephone number.” (At a subsequent interview, he said that he was in the habit of jotting down notes of important events on walls in the house.) He said that the serial numbers on the closet door were of large bills that Fisch had given him to buy shares.

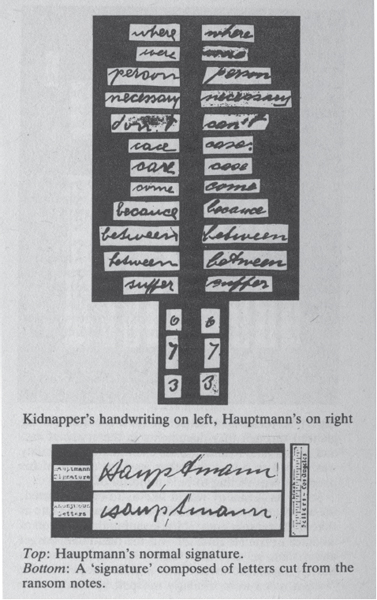

Handwriting experts compared the kidnapper’s writing (on the demands to Lindbergh and on the ransom-arranging letters to Condon) with specimens of Hauptmann’s writing before his arrest. In the summer of 1932, detailed analysis of the notes had proved that, as was to be expected, the writing was disguised; but the analysis had picked up many repeated letters and words that the kidnapper had failed to disguise—also a number of misspellings and peculiar locutions. Since the analysis, one of the experts had examined the writing of more than three hundred men questioned by the police, without finding a single specimen with sufficient resemblances to the notes. The kidnapper/ Hauptmann comparisons left the experts in no doubt that no one but Hauptmann could have written the notes. Their conviction was based not only upon matching formations but also upon Hauptmann’s writing of a dictated “test paragraph” containing words that the kidnapper had misspelt—for instance, “anything” and “something” as “anyding” and “someding,” “our” as “ouer,” “were” as “where,” “later” as “latter.” Hauptmann misspelt every one of the “trick words” in exactly the way the kidnapper had.

Almost a year before, Arthur Koehler had suggested to the police that they should interview every customer of the National Lumber & Millwork Company in the months preceding the crime; the suggestion had not been followed up. But by the time that Koehler was summoned to Hauptmann’s house, a few blocks from the timber yard, a checking of the company’s records had shown that Hauptmann had bought ten dollars’ worth of timber there at the very end of 1931. Hauptmann either could not or would not say what he had used the purchase for. Koehler inspected the woodwork in and of the house—lastly, that in and of the attic. There, he immediately noticed that part of one of the flooring boards was missing; that it had been sawn off was evident from the fact that sawdust clung to the lathes at the end of the truncated board. He compared Rail 16, the odd one out, with the board. Not only were the two pieces of the same type of wood and the same lateral dimensions, but the graining and the annual rings corresponded. And when an end of Rail 16 was placed near the end of the board, the four nail-holes in the rail exactly matched four nail holes in the joist below; two of the holes in the rail had been driven in diagonally, at the selfsame respective angles as the matching holes in the joist. With the holes aligned, there was a two-inch gap between the rail and the board, indicating to Koehler that the maker of the ladder, having sawn off rather more than he needed, had sawn the rail to the required length. Seeking further evidence that Hauptmann had made the ladder, Koehler examined the contents of the carpenter’s chest in the garage-cum-workshop, paying particular attention to the planes, the blades of which he examined under a microscope, scrutinizing them for nicks and other imperfections. He used the planes on blocks of “neutral wood” and found that one of them left ridges that coincided exactly with the ridges he had observed in hand-planed surfaces of a side of the ladder and all of its rungs; the matching of the ridges, as unique to a particular plane blade as fingerprints are to a particular hand, was apparent to the naked eye. Proving that the plane was Hauptmann’s, a bracket in the garage bore the same ridges.

At identification parades, Hauptmann was picked out by various eyewitnesses—and, though not on a parade, by an ear-witness, Lindbergh, who said that Hauptmann’s voice was that of the man he had heard calling out to Condon at St. Raymond’s Cemetery on the night when the ransom was handed over. Condon was both an eye- and an ear-witness, saying that Hauptmann was definitely the “Cemetery John” with whom he had negotiated on two occasions, for nearly two hours in all. Among others who claimed to recognize Hauptmann were the cabdriver to whom the criminal had given a letter for delivery to Condon; a woman who said that, during the “Jafsie period,” she had seen Hauptmann watching Condon at a Bronx railway station; a box-office girl at a Manhattan cinema, who said that he was the man who in November 1933 had paid for a ticket with a ransom bill; and two men living near Hopewell—one an illiterate hillbilly with an unsavoury reputation, the other an octogenarian whose eyesight had deteriorated—who said that they had seen Hauptmann near the Lindbergh estate shortly before the kidnapping. Condon was the only one of the eye/ear-witnesses whose evidence was stronger than doubtful.

The trial of Hauptmann began on the second day of 1935 in the pretty courthouse in the small town of Flemington, New Jersey, which was jam-packed throughout the trial with journalists (including Damon Runyon, Walter Winchell, and Ford Maddox Ford), press photographers and movie cameramen, and sightseers (including show-business personalities such as Jack Benny and Clifton Webb, and members of high society, some accompanied by their publicity agents). The prosecution was led by David T. Wilentz, the pugnacious attorney general of New Jersey, the defence by Edward J. Reilly, “the Bull of Brooklyn,” who had been briefed in more than two thousand murder trials and whose fee in the Hauptmann case was partly paid by a newspaper in return for “exclusives” from the defendant and his wife. The trial dawdled on till 13 February, when the jury of eight men and four women, all local people, each now famous wherever newspapers were circulated, having deliberated for just over eleven hours, returned a verdict of “guilty of murder in the first degree,” without recommendation of life imprisonment.

There were, of course, any number of appeals, each postponing the execution. Meanwhile, Anna Hauptmann went on a fund-raising tour of places with large populations of German Americans and told audiences at Hauptmann-is-Innocent rallies what they wanted to hear: that her husband was the victim of a frame-up, chosen as such simply because he was German. Near the end of 1935 (shortly before the Lindberghs, wanting to get away from it all, sailed for England with their second son, Jon, intending to settle there), Harold G. Hoffman, the governor of New Jersey, who happened to be planning a bid to become the Republican candidate for the presidency, got himself on to front pages and into editorials by saying that he had visited Hauptmann in his cell and that he had grave doubts as to whether the case had been solved. Hoffman kept himself in the news for the next couple of months—by declaring his faith in Hauptmann’s Fisch story and pooh-poohing Koehler’s findings, by announcing that he had hired private detectives to reexamine the case, by talking of “new evidence” (all of which turned out to be worthless, either because it was immaterial or because it was proved to have been fabricated), and, in January 1936, by granting Hauptmann a thirty-day stay of execution—during which a vainglorious detective named Ellis Parker, a friend of Hoffman’s, entered the case. A few days before Hauptmann was again scheduled to die, Parker and his son produced a detailed “confession” signed by Paul Wendel, a disbarred lawyer—but refused to produce Wendel until Attorney General Wilentz insisted on knowing where he could be found: in a mental institution, where he had been confined for some weeks on Parker Senior’s orders. The execution, rescheduled to take place on the last day of March, was postponed while a grand jury pored over Wendel’s “confession” and discussed his account of how he had been kidnapped by a gang, kept in a cellar in Brooklyn, where he had been tortured till he was ready to sign anything, and then taken to the mental institution.

On Friday, 3 April 1936, shortly after the grand jury voted to drop the Wendel case, Hauptmann, still protesting his innocence, was executed in the electric chair at Trenton Prison.

That necessarily brief account does not, of course, include every bit of the long story. But I don’t think I have left out any points of real importance. If I have, the omissions are unintended, not meant to mislead. I shall, in a minute, refer to points that another writer has suggested are important but which, in fact, are not. If my account contains any inaccuracies, they must be of a trivial nature. I have not amended truths to suit a purpose.

Bruno Richard Hauptmann was guilty of the kidnapping and murder of the Lindbergh baby.

I state that, not as an opinion, but as a fact.

Harold G. Hoffman and Ellis Peters were not the first persons, nor (as I intimated when I began) the last, to try to muddy the truths of the case. For a discussion of some of the quaint theory books published before 1985, I can do no better than quote Patterson Smith, the leading American bookdealer specializing in factual crime material:

Although it is now not often realized, the Lindbergh kidnapping attracted sceptics from the start. Just after the story broke in 1932, Laura Vitray, a Hearst reporter, rushed into print with a little-known book, The Great Lindbergh Hullabaloo: An Unorthodox Account. Unorthodox it is.

Vitray, sensing a hoax, wrote derisively of the Lindbergh family, referring to the child as “the golden-haired Eaglet” and accusing certain vaguely defined “powers” of having “deliberately” arranged the Lindbergh “kidnapping,” not for ransom, but as a story, to divert public attention from the grave disaster that threatens this nation at their own hands today.”

Laura Vitray had a sister sceptic in Mary Belle Spencer, a Chicago lawyer who seems to have had an animus against the massive law-enforcement effort that was thrown into the hunt for the Lindbergh child and its kidnapper. In 1933, after the discovery of the child’s body but before the arrest of Hauptmann, she published a pamphlet bearing the cover title, No. 2310, Criminal File: Exposed! Aviator’s Baby Was Never Kidnapped or Murdered.

Her argument was that no crime had been shown to have been committed, the infant being perfectly capable of having wandered off on its own to meet its death by animals in the woods. She presents the text of a mock trial in which she defends a vagrant “John Doe” who has been indicted for kidnap and murder. In her burlesque, she makes thinly veiled substitutions for names prominent in the case, such as “Limberg” for Lindbergh and “Elizabeth Gah” for Betty Gow. (For reasons unknown to me, on the front cover she has covered the original line of type, which read “Limberg’s Baby,” with a correction strip reading “Aviator’s Baby.”)

This curious work, which is now rare, almost had severe consequences for the trial of Hauptmann. Prior to the proceedings, copies were mailed to the panel of jurymen, causing the judge to consider granting a change in venue.

H. L. Mencken said that the Lindbergh case was “the biggest story since the Resurrection.” Concerning Hauptmann’s guilt there seemed to be little doubt, for he was tied to the crime by a web of circumstantial evidence which, taken as a whole, was so strong that it seemed that no one possessed of reason could challenge the certainty of his guilt.

But a challenge did come. Anthony Scaduto, in Scapegoat (1976), marshalled some 500 pages of evidence and argument in an attempt to demonstrate that Hauptmann, at most guilty of extortion, ended his life the victim of a judicial murder by the state. Scaduto’s arguments, given additional publicity by Hauptmann’s widow, seeking vindication for her husband, attracted much attention and gained many adherents.

An issue is raised here on which I wish to ruminate. In some forty-eight years of dealing in material on criminal justice history, I have had contact with many writers and researchers seeking material for new books on past crimes. Often a product of such endeavours will be the first of its kind on a given crime; often it will be a retelling, with added information or a new analysis, of a familiar crime narrative; often it will add to the literature yet another theory in explanation of a crime never satisfactorily explained.

On rare occasions, of which Scapegoat is one, it will offer a radically divergent theory of a crime hitherto considered settled. Of all crime books published, those posing revisionist theories tend to attract the greatest media attention. They are “news.” Far from merely adding to our knowledge of a past event or reembellishing a tale previously grown stale in the telling, they say to us, “You’ve been wrong about this case.” And if someone is thought to have been unjustly convicted and executed, the news value is all the stronger.

It has, after all, been observed that Americans have a greater sense of injustice than of justice. When a revisionist account reaches reviewers, the arguments put forward by its author can seem extraordinarily compelling, for very often the book does not aim for balance but selects only those facts that support its divergent thesis.

Moreover—and this is very important—the reviewer of a book on crime written for the general public often has little or no background in the case which could help him weigh the author’s novel contentions against countervailing evidence. The reviewer sees only one side of the story, and it usually looks good.

If you infer from these musings that I do not accept Anthony Scaduto’s thesis about Hauptmann’s innocence, you are correct.

Another quote, this one from the brilliant American lawyer Louis Nizer, who, having coined the term “analytical syndrome,” explains:

It is possible to take the record of any trial and by minute dissection and post-facto reasoning demonstrate that witnesses for either side made egregious errors or lied. Then, by ascribing critical weight to the exposed facts, the conclusion is reached that the verdict was fraudulently obtained. This was the process by which the Warren Commission Report [on the assassination of President Kennedy] was challenged in a spate of books. To cite just one illustration, a constable deputy sheriff described the rifle which had been found on the sixth floor of the Book Depository Building, Dallas, as a Mauser, instead of a Mannlicher-Carcano, which it was. Out of this innocent error, due to ignorance or excitement, sprouted the theory that the real assassin’s rifle had been spirited away and Lee Harvey Oswald’s rifle planted on the scene to involve him. Multiply this incident by many others, such as someone’s testimony that shots were heard coming from the mall, and the “hiding” of the death X-rays of the President (since revealed), and you have a gigantic conspiracy by foreign agents, or government officials, or New Orleans homosexuals, or lord knows what, to fix the blame on an innocent man, Oswald. Of course, all this was nonsense, and subsequent events have confirmed the accuracy of the Report.

The analytical syndrome can be used to discredit any verdict, from the commonest automobile negligence case to the most involved anti-trust or proxy contest.

Anthony Scaduto uses the analytical syndrome. And so does Sir Ludovic Kennedy, the British television personality who in 1985 published a 438-page book, The Airman and the Carpenter: The Lindbergh Case and the Framing of Richard Hauptmann, which must have convinced many, perhaps most, of its readers that Hauptmann was the victim of a miscarriage of justice.

Since Kennedy’s is the most recent Hauptmann-was-innocent book, and since he repeats the Scaduto notions that he likes best, I shall concentrate on his view of the case.

First, though, let me quote his explanation of what invariably persuades him to produce so-and-so-was-innocent books and of what his method of investigation is. My interpolations may, at this stage, seem to be nitpicking, but I promise you that they are pertinent.

Kennedy: “I have been asked whether in cases I have investigated I have ever been convinced of the complainant’s guilt. The answer is no, because I have never pursued cases where I have been uncertain about guilt or innocence.” (The words “guilt or” are redundant, for Kennedy has only pursued cases where his initial instinct assured him that the persons found guilty were innocent.) “In those cases I have written about, my initial instincts that the person in question was not guilty have been fully confirmed by subsequent investigations.” (“Fully confirmed”? To his own satisfaction, he must mean.) “It should however be emphasized that, contrary to popular belief, cases of guilty men proclaiming their innocence and continuing to do so with evidence to back it up are so rare as to be almost non-existent.” (Heaven knows what that means. One assumes that the backing-up evidence refers to the proclamations rather than the innocence of the guilty men. Perhaps not: as I shall demonstrate, Kennedy, following the general example set by Humpty Dumpty, does tend to use the word “evidence” rather loosely—as a description of things that may have happened, things that are rumoured to have happened, and things that certainly didn’t happen. In any event, how does Kennedy know that his statement is true, considering that he has never investigated any such cases?) Speaking of his method of investigation, Kennedy says, “My starting-point has always been a presumption of innocence, and in all my cases I have found a narrative story based on that presumption to be far more convincing than a continued assumption of guilt.”

Using the Kennedy Method (which is far more complicated than he has just made it out to be), one would have no difficulty in “proving,” say, that Adolf Hitler was pro-Semitic—or, having plumped for a presumption of guilt, that St. Francis of Assisi was a vivisectionist. Actually—confirming popular belief—the annals of crime are strewn with undoubtedly guilty persons, many of them users of the analytical syndrome, who never wavered from pleading innocence.

Here is one of Kennedy’s several versions, all much the same, of how he came to the conclusion that Hauptmann was innocent:

“The place was my hotel bedroom, the time around 8 A.M. [on a day in 1981]. As one often does in New York at that time of day, I was flicking idly through the television channels while awaiting the arrival of orange juice and coffee. I did not even know which channel I was tuned to when there swam into my vision a very old lady proclaiming with vehemence that her husband was innocent of the crime of which he had been convicted. I sat up and paid attention for this was, as it were, my territory. … Slowly it dawned on me—for the scene had been set before I had tuned in—that the old lady was none other than Anna Hauptmann, the widow of Richard Hauptmann. … And then I remembered from Eton days a picture that would be seared on my mind for ever, a full-page photograph of the haunted unshaven face of Richard Hauptmann as it first appeared after his arrest and then again, on the day of his electrocution two years later.

And now, nearly half a century on, here was his widow not only proclaiming his innocence but telling Tom Brokaw (and this was the peg for the interview) that as a result of new information about the case, she was taking out a suit against the State of New Jersey for her husband’s wrongful conviction and execution. … I felt the old adrenalin surging through me and a sense of heady exhilaration; for I thought it improbable in the extreme that an old lady in her eighties would have agreed, forty-four years after her husband’s death, to have travelled all the way to New York to appear on an early morning television show to assert her husband’s innocence and launch a suit against a powerful state if she knew (and she would have known) that her husband was guilty; not unless she was out of her mind, and she did not seem to me to be that.

Let us examine Kennedy’s criteria for an “extreme improbability”:

1. That “an old lady in her eighties would have agreed… to have travelled all the way to New York to appear on an early morning television show.” The old lady in her eighties (as opposed to a young lady in her eighties, who really would deserve sympathy) was as fit as a fiddle. Near the end of Kennedy’s book, more than four hundred pages away from his account of Mrs. Hauptmann’s appearance on television, he reveals that, four years later, she was “still amazingly active and mentally alert.” Her journey “all the way to New York” sounds a very long way indeed; but, in fact, she had only come from Philadelphia (which is a shorter distance from Hopewell than Hopewell is from New York); all her expenses were paid, all arrangements made, by the television company, who no doubt also paid her an appearance fee. With no disrespect to her, it is reasonable to think that she would have been glad to put herself out far more than she did in order to appear on a popular television chatter show, doing her utmost to sway public opinion in favour of her claim that her husband had been “Wrongfully, Corruptly, and Unjustly” executed—and, incidentally, that she was entitled to damages of a hundred million dollars.

2. That unless Mrs. Hauptmann was out of her mind (and she seemed perfectly sane to the perfectly sane Kennedy), she would not have gone to such trouble “if she knew (and she would have known) that her husband was guilty.” Excluding Kennedy, Scaduto & Co. (and Mrs. Hauptmann’s lawyer, who was presumably working on a contingency-fee basis that he would receive a percentage of any profits from the legal action), it is impossible to think of any campaigning pro-Hauptmannite whose utterances on the case should be taken with more salt than those of Mrs. Hauptmann. Following her husband’s arrest, she too was grilled; her questioners were unable to break her story that her husband had told her nothing of the ransom money hidden at first in the house and then in the garage, she had never chanced on any of it, and she had accepted his explanations as to how he, though hardly ever working, was able to pay the domestic bills, buy luxury items, and send her off to Germany for a three months’ holiday. Supposing her story was true, then there is no doubt whatsoever that Hauptmann, if he was the kidnapper, never told her that he was, and never gave her the least reason for suspecting that he was. Therefore (and quite apart from the fact that it would be most unexpected if she, a determinedly trusting and loving wife, no less determinedly trusting as a widow, were ever to speak of any suspicion of Hauptmann that may have crossed her mind against her will), all that she can say firsthand in defence of her husband is that, until his arrest, she had no reason for thinking that he was connected in any way with any crimes committed in the spring of 1932. The best one can say of that is that it is negative evidence—about as useful as the evidence of an eyewitness who claims that he didn’t witness anything. A proverb seems apropos, not only of Mrs. Hauptmann but also of her confederates: “There are none so blind as those that will not see.”

In every complex criminal case, the evidence for the prosecution can be divided into two sorts: salient and secondary. If the salient evidence stays intact, no amount of doubt concerning any, even all, of the secondary evidence has the slightest weakening effect upon the strength of the salient evidence—which, in the case of Hauptmann, was this:

1)He had spent some of the ransom money and was in possession of a large part of the remainder, which he had hidden away in his garage, some of it in specially carpentered hidy-holes.

2)He was the writer of the ransom notes.

3)Part of the ladder specially carpentered for the kidnapping had been sawn from the floor of carpenter Hauptmann’s attic.

4)He had written John F. Condon’s address and telephone number on the inside of a closet door in his home.

5)He had given up full-time work on the very day that the ransom was paid.

Let us look at the first four points one by one—leaving out the last, which was and is undisputed.

1) Hauptmann’s explanation for his possession of the ransom money was that a shoebox had been left with him by Isidor Fisch, who had since died, and that, after Fisch’s death, he, Hauptmann, who meanwhile had given no thought to the box, let alone been at all curious as to what it contained, had accidentally opened it and found a small fortune, which—without thinking twice, and without saying a word to his poor, hardworking wife—he had treated as a windfall (but one which, though it never occurred to him that he might be handling “hot money,” he felt that he needed to stash away in various hiding places, some of which he used his long-unused carpentry tools to create).

There isn’t a scrap of evidence that supports Hauptmann’s Fisch story. But Kennedy does his best—or rather, worst—to lead readers up a garden path to a belief that the story was corroborated. Some of those readers will have been taken in. One of Kennedy’s methods is to state something with complete assurance in the hope that readers will assume that they must have missed or forgotten his earlier proving of the statement and will therefore accept his statement as gospel. His first more than slight reference to Isidor Fisch appears on page 134 and is given particular emphasis because it is at the start of a subchapter: “Of all the diverse characters who people the Lindbergh kidnapping story, the most mysterious, the most enigmatic, the most sinister is undoubtedly Isidor Fisch.” It is safe to say that Kennedy would feel that he had been treated disgracefully, unfairly, improperly, if the author of an article about him began by saying: “Of all the diverse characters who have written about the Lindbergh kidnapping case, the most mysterious, the most enigmatic, the most sinister, is undoubtedly Ludovic Kennedy”—and that he would be still more upset if the author, continuing, failed (as, of course, he would) to substantiate the statement. Yet Kennedy doesn’t seem to care that he fails to substantiate his statement about the dead Fisch.

The most Kennedy is able to pretend to prove in his efforts to bolster the Fisch story concerns Hauptmann’s best friend, Hans Kloppenburg. On page 243, he says, “A key witness in the matter was Hans Kloppenburg, who had seen Fisch arrive at Hauptmann’s home with the shoe-box, hand it to Hauptmann, and the two of them go into the kitchen with it.” A few of those readers who have frail memories, and most of those with a healthy suspicion of anything that Kennedy says as if stating a fact, will thumb back a hundred pages to the account of the “handing over the shoe-box” incident: “on December 2 [1933], the Hauptmanns gave a farewell party for Fisch [who was sailing to Germany on the 6th]. … When Fisch came he brought a package wrapped in paper and tied with string which Kloppenburg, who was standing by the door, described as a shoe-box.” Kennedy then says—but without explaining that he is now quoting, would you believe, from Hauptmann’s story—that “Fisch asked if Hauptmann would look after the package while he was away … and Hauptmann readily agreed.”

So between Kennedy’s two accounts, a package wrapped in paper, tied with string, and described by Kloppenburg as a shoebox becomes “the [my italics] shoe-box”; and the package, only carried by Fisch in the first account, is handed over to Hauptmann in the second. Perhaps Kloppenburg did describe the package as a shoebox when interviewed by Kennedy or his researcher half a century after his fleeting glimpse of it; but at the trial, answering a question from his best friend’s counsel, he described it only as a package and gave a rough idea of its dimensions—which made it as likely to have been a boxed strudel, Fisch’s contribution to the party fare, as a shoebox filled with ransom money. Under cross-examination, Kloppenburg admitted that he “did not remember seeing Fisch leave the Hauptmann home on the night of the farewell party, and therefore could not say whether Fisch took the package away with him.” Imagine what Kennedy would have made of it if Kloppenburg had testified that Fisch left empty-handed: he could have turned that into “clinching evidence” that the shoebox story was true—as easily as anyone disagreeing with him, and willing to swallow the shame attached to resorting to a similarly fallacious way of arguing, might use the empty-handedness to turn the strudel possibility into the strudel “fact.”

2) Whoever kidnapped the Lindbergh baby also tricked the $50,000 from John F. Condon. There is conclusive proof of that in the fact that all of the ransom notes, including the one left in the nursery, bore the overlapping-circles “singnature”; if anyone, like Kennedy, insists upon having incontrovertible corroboration of that conclusive proof, there is the fact that the baby’s sleeping suit was mailed to Condon by the ransomer. Kennedy may, without thinking, protest that there is a possibility that more than one person took part in the kidnapping—that the person who left the note in the nursery was not the writer of that note or the subsequent ones. All right—but I doubt if he, inventive as he is, can conjure that point around to make an ersatz semblance of help for his argument that Hauptmann was neither a kidnapper nor the ransomer—just a poor, framed illegal immigrant who, having been given a small fortune to look after, decided, as any sensible person would, to keep it for himself.

At Hauptmann’s trial, the prosecution called eight handwriting examiners, all of whom were convinced that the ransom notes had been written by the defendant. Before those examiners gave evidence, the defence had half a dozen examiners prepared to say the opposite; but by the time the latter were needed, all but one had dropped out, some admitting that they had done so because they had completely changed their minds. The defence touted around for replacements, but, unable to entice a single one, were left with the only steadfast member of the original half-dozen—and had difficulty in persuading the judge that he, John Trendley, of East St. Louis, was qualified to give evidence as an expert witness.

One doesn’t need to be a handwriting examiner to know, from looking at the hundreds of word and letter comparisons presented at the trial, that Hauptmann wrote the ransom notes. The resemblances between words and letters in the notes and words and letters in documents written by Hauptmann cannot be explained away. And, as if further proof were needed, words and letters in a “farewell declaration of innocence” that Hauptmann sent to Governor Hoffman demonstrate his guilt.

What does Kennedy make of this? Not a lot. Though he includes J. Vreeland Haring’s classic and massive book, The Hand of Hauptmann, which is packed with illustrations of the comparisons, among what he claims are the “sources” of his book, he makes no obvious use of its contents. Despite the fact that he includes seventy-five halftone and line illustrations in his book, not one is of a handwriting comparison—which surely means that he was unable to find a single comparison which he thought doubtful enough for him to pooh-pooh. What does he say about the prosecution’s handwriting examiners? Not a lot. Inter alia, this: that they looked “like senior members of an old folks’ bowling club.” (In fact, only one of the eight was older at the time of the trial than Kennedy was when he published his book.) What does he say about the handwriting evidence? Not a lot—indeed, even less. This: “As the combined testimonies [of the handwriting examiners for the prosecution] run to some five hundred pages of the trial transcript and are much concerned with technicalities—the shape of a ‘t’ or the curl of a ‘y’—and as their conclusions were later challenged by the defence’s lone expert using the same material, it is not proposed to go into these in any detail.” Five hundred pages of evidence against Hauptmann, and he does not propose to go into it in any detail!—(a) because much of it is technical, as much expert evidence at most trials is—does he mean, then, that all such technical expert evidence can be disregarded by jurors? and (b) because the defence had a “lone expert” so reckless or desperate for a fee that, having glanced through fifty documents in the space of two and a half hours (under cross-examination, Trendley was forced to admit that that was the extent of his prep), he was willing to be a minority of one.

Handwriting sample of Bruno Richard Hauptmann and kidnapper (from The Modern Murder Yearbook)

Handwriting samples from the ransom note for the Hauptmann case (from The Modern Murder Yearbook)

So far as Kennedy would like us to be concerned, the fact that Hauptmann’s handwriting was the same as that of the ransom notes is irrelevant to the question of whether or not Hauptmann was the ransomer. Forget about that, he says hopefully—let’s concentrate on the all-important matter that words misspelt in the ransom notes were similarly misspelt by Hauptmann in his “request writings.” Those similarities, every single one of the many of them, are easily explained away by Kennedy. Speaking of all investigators, he says, “When contradictory evidence appears, they ignore it, unwilling to admit that their original belief was false; and the longer the original belief is held, the more difficult it becomes to shift. When no corroborative evidence appears to reinforce the belief, it has to be manufactured.” Ergo, the investigators who got the request writings from Hauptmann forced him to misspell certain words in the same way that those words were misspelt in the ransom notes. Isn’t that obvious? Well, it might be—but what of the fact that many of the misspelt words appear in the same misspelt way in documents written by Hauptmann before his arrest? I doubt if you will be surprised to learn that Kennedy tries to gloss over the obvious answer to that question. Rather surprisingly, he does not seek to reincarnate a notion that the defence had at the start of the trial but dropped once it was established that Hauptmann and Fisch were not introduced till after the kidnapping: the notion was that Fisch had, for some reason or other, forged Hauptmann’s writing on the ransom notes. One last point about those notes: proof that they were not written by Fisch is as undoubtable as the proof that they were written by Hauptmann.

3) Even if only in terms of persistence, Arthur Koehler’s work in tracking the kidnap ladder to the man who made it is among the most admirable pieces of detection of all time. There is not a scrap of evidence to suggest that Koehler (who completed the legwork part of his investigation nearly a year before anyone had any reason to suspect Hauptmann) was not entirely honest. The same can be said of Koehler’s helper, Lewis Bornmann, of the New Jersey State Police. Kennedy, irritated by such honesty, sneers at “these two jokers.” On the same page as that sneer (221), he states that Koehler’s discovery that ladder rail No. 16 was from the floor of Hauptmann’s attic is completely discredited by the fact that he did not instantly “proclaim it [the discovery] to the world.” On the same page as the sneer and the statement, he speaks of a defence “trump card” (in fact, a trumped-up card: it was some nonevidence of an alibi, which I shall refer to shortly)—and does not consider that it is at all devalued by the fact that the defence kept it up their sleeve for months. Heads, he wins—tails, honest investigators lose.

He is forced to use the chestnut ploy of asking the reader to be as reasonable-minded as he is: is it likely that a sensible person (Hauptmann) would do a silly thing (cut timber from his attic for a kidnap-ladder rail)? Since almost all sensible criminals who are arrested are found out because they have done silly things, if all defence counsel used the ploy with invariable success, almost all sensible criminals would be acquitted. That might please Kennedy, but I would venture to suggest that all other sensible law-abiding persons would take a dim view of it. The fact that Hauptmann made the ladder from different sources is no more strange than the fact that, rather than finding or making one hiding place for his “windfall,” he found or made more than one.

Kennedy, incidentally, accepts Hauptmann’s description of the ladder as “ramshackle”—meaning that it must have been made by someone without carpentering skills. Kennedy has seen the ladder. So have I. Even if I spent months trying to, I certainly couldn’t make as good a job. Could Kennedy? If he says yes, and has a few months to spare, would he mind putting his manual mastery where his mouth is? If he likes, he can appoint a noncarpenter proxy. Is that a fair challenge?

As part of Governor Hoffman’s reexamination of the case, a so-called wood expert visited the attic—and told Hoffman that he could prove that Rail 16 had not come from there, saying that his conclusion was partly based on the fact that when nails were pressed through the holes in the rail and into the holes in the joist, they protruded a quarter of an inch. Koehler was summoned to the house, and it was discovered that, since his last visit, quarter-inch wooden plugs had been pushed into the holes in the joist. Kennedy ascribes the post-trial jiggery-pokery in the attic to an act of nature—or rather, he accepts without question Hoffman’s subsequent comment that an unidentified someone had told him that the plugs were just “fibrous fragments” that, in the abnormal course of dead-wooden events, had sort of congealed together to look the spitting image of plugs. Still relying on Hoffman, he quotes him as saying (in 1936), “I have in my possession a photograph of the ladder made the day after the commission of the crime. It is a clear photograph, in which the knots and grains are distinctly shown, and Rail 16 can be easily identified; but neither in the original nor in a copy magnified ten times can the alleged nail-holes be found.” Has anyone ever seen the photograph or the enlargement? Has Kennedy? Had Hoffman? The four nail holes are clearly visible in police photographs among those taken of the ladder on 8 March 1932. It is all very well for Kennedy to admit (well away from the Hoffman quote) that Hoffman was posthumously proved to have embezzled $300,000 from the state he governed—and almost as well to comment that Hoffman’s crookedness “in no way diminishes the courageous stand he took in championing the cause of Hauptmann’s innocence”—but it is reasonable to assume that if anyone who contributed to the verdict at Hauptmann’s trial had afterward turned out to be crooked, even only slightly so compared with Hoffman, Kennedy would have used that fact as a reason for disbelieving any anti-Hauptmann evidence from that contributor. Come to think of it, one doesn’t need to assume: Kennedy, in seeking to discredit the eyewitness evidence of the Hopewell hillbilly I mentioned on page 223 (whose evidence was, surely everyone agrees, dubious), reports that, a couple of months after the trial, the hillbilly was “clapped into jail for stealing a road grader and selling it for $50.”

Kennedy doesn’t seem to have understood all of Koehler’s evidence. For instance, there are times when he speaks of Rail 16 when what he is really talking about is the board in the attic from which, according to Koehler, Rail 16 was cut. In his account of the quizzing of Koehler in the attic on 26 March 1936, he says that Hoffman’s “wood expert,” Arch Loney (can anyone doubt that Loney was the plug-ugly?), “pointed out that Rail 16 [actually, the board] was a sixteenth of an inch thicker than the other boards, but Koehler didn’t have an answer to that.” The statement that Koehler was stumped is untrue. Having already answered questions from Loney that showed that the latter’s knowledge of carpentry was rudimentary, Koehler patiently explained that “as the attic was unfinished, uneven flooring was to be expected.” After a couple more questions from Loney, and immediate answers from Koehler, an observer said to Attorney General Wilentz, speaking loudly enough for everyone to hear, “I can’t believe that Koehler has been brought all the way from Wisconsin for this!” That exclamation seems to have prompted Hoffman—not Loney, you notice—to demonstrate that nails pushed through the holes in Rail 16 and into the holes in the joist did not go all the way down (because, as was proved later in the day, plugs had mysteriously become inserted in the holes in the joist).

4) During the week after Hauptmann’s arrest, he twice, on separate occasions, neither of them a third-degree session, admitted that he had written John F. Condon’s address and telephone number on the inside of a closet door in his home. At the trial, when cross-examined about the writing, he got into a hopeless tangle in trying to explain away his original explanation. One can understand why. Clearly, when Hauptmann was first asked about the writing—shown it—he, flustered because he knew that the writing was his, believed that the writing was undoubtedly identifiable as his, felt that there was no point in lying that he had not made the notations, and gave the only explanation for them that he could invent: that he was in the habit of jotting down references to important events on doors (a habit of which there was no other sign in the house).

Kennedy, who gets angry about hearsay that doesn’t suit his purpose, is only too happy to accept hearsay that does. On page 204 he says, no ifs or buts, that a Daily News reporter, Tom Cassidy, “planted” the writing “as a joke … either late on September 24 [1934] or on the morning of the 25th. … He then smudged the writing as though an attempt had been made to wipe it out.” Well, that’s sure enough, isn’t it? Isn’t it? Well, no—because it turns out that “Cassidy’s joke” is something that in the late 1970s was rumoured to have been rumoured toward the end of 1934: rumoured both times, what’s more, by reporters—the 1934 ones among those who, so Kennedy says four pages later, “went overboard completely, not hesitating to print all sorts of allegations and rumours as fact.” Not satisfied with the little that the reporter-rumourers of the 1970s had to say, Kennedy adds one of his own, that “Cassidy got word to the Bronx police”—presumably so as to make his joke hilarious. According to all three of the 1970s rumourers, Cassidy was too pleased with his joke to worry that, if he had really perpetrated it, he could be imprisoned: “Hell, he bragged about it all over town.” “He admitted it to me and Ellis Parker, he told everybody about it.” “He told a bunch of us.” Like most rumourers, these protested too much: if the joke was such common knowledge, how is it that the defence lawyers were never let in on it? Kennedy doesn’t explain that (not even when, exactly a hundred pages later, he speaks of a moment during the trial “after Wilentz had been questioning Hauptmann about Tom Cassidy’s writing [my italics] on the inside trim of the closet”).

Perhaps he believes that Hauptmann’s leading counsel, Edward J. Reilly, did hear about the joke and decided that it must not be mentioned, for fear that it might help to get his client acquitted. Kennedy, you see, suspects that Reilly was actually a mole-type extra counsel for the prosecution. If ever a statement deserved to be followed by several exclamation marks, that one does. Kennedy’s suspicion is based on two things, one being the fact that part of Reilly’s fee had been guaranteed by “the anti-Hauptmann Hearst Press” (in return for exclusives from Hauptmann and his wife), the other being Kennedy’s feeling that Reilly did not ask all the questions he should have asked. If Kennedy knew anything about the art, which it is, of cross-examination, he would know that the reason for virtually all of the Reilly unquestions which he cites is covered by a maxim of cross-examination: never ask a question if you don’t already know the answer.

It is surprising if Kennedy has never heard that maxim, for he himself, as an investigator, pays great regard to a variation on it: never ask a question if there is the slightest risk of getting an answer that does not accord with your preconception.

Twenty pages after “proving” that Tom Cassidy was a psychopathic joker, Kennedy reinstates Cassidy as an upright citizen, his word even better than his bond, the last person in the world one would suspect of fabricating evidence. This reinstatement is in aid of “proving” that Hauptmann did a full day’s work at the Majestic Apartments, Manhattan, on 1 March 1932, in the evening of which the Lindbergh baby was kidnapped. Cassidy, so Kennedy says, unearthed payroll records showing that Hauptmann worked at the Majestic Apartments till 5 P.M. (A few Kennedy sentences later, “5 P.M.” becomes “5 or 6 P.M.”) Finding Kennedy’s Majestic argument incomprehensible, even after umpteen attempts to fathom it, I gave photocopies of the pages to four friends—a barrister, a coroner, a forensic scientist, a book-publisher’s editor—and was relieved to hear from all four that they too were baffled. The trouble, I think, is that Kennedy, for once believing that he has a lot of evidence that needs no help from him, presents all of it—so much that one cannot see the wood for the trees.

But supposing that the Majestic argument is valid, the documentary evidence for it untampered with by pro-Hauptmann researchers, it certainly doesn’t mean that Hauptmann had a sort of alibi. Kennedy is guessing again when he says, on page 173, “The police realized that if he [Hauptmann] was working at the Majestic Apartments until five or six [sic] on Tuesday, March 1, it was unlikely that he was putting a ladder up against the nursery window at Hopewell three or four hours later.” Let us allow Kennedy his unsubstantiated assumption that Hauptmann worked an hour of overtime, from five till six. Even if Hauptmann had driven the sixty miles from the Bronx to Hopewell at the dangerously slow average speed of 20 mph, he would have arrived at the Lindberghs’ house with ample time to spare before the kidnapping, at about ten minutes past nine. Not that he would have wanted ample time: the longer he loitered near the house, the more danger there was that he or his parked car would be observed.

Kennedy, as well as saying that Hauptmann almost had an alibi for the time of the kidnapping, claims that Hauptmann had a complete alibi for the night of Saturday, 2 April, when Condon handed over the ransom money to “Cemetery John”: “It being the first Saturday of the month, Hauptmann and Hans Kloppenburg had their regular musical get-together.” At the trial, under direct examination, Kloppenburg testified that he “recalled being at the Hauptmann home on the night of 2 April 1932, it being a custom to gather for an evening on the first Saturday of each month.” (Kloppenburg’s helpfulness to Hauptmann is rather hard to reconcile with the tale he told half a century after the trial, which was that he had first been grilled by detectives—“They were trying to scare me with the electric chair so that I wouldn’t testify”—and then by David Wilentz: “A day or so later, I think it was the day before I testified, there was a story in the newspapers that police were about to arrest a second man in the kidnapping. That was me they were talking about. They were trying to scare me so I would shut up. And I was scared.”) Under cross-examination, Kloppenburg “admitted telling the Bronx District Attorney, shortly after Hauptmann was arrested, that he could not remember when he saw Hauptmann in March or April 1932, because ‘that is too long ago.’” Under redirect examination, he gave two further reasons for remembering the date of the evening of music: “There was some sort of April Fool joke” and “Mrs. Hauptmann spoke of wanting to go and see her niece the following day.” (Did anyone else, even Tom Cassidy, play April Fool jokes after April Fools’ Day? So far as anyone seems to know, Mrs. Hauptmann may have paid frequent Sunday visits to her niece—or frequently, on Saturdays and other days, spoken of wanting to see her niece.) Under recross-examination, Kloppenburg admitted that he had “talked with Detective Sergeant Wallace, of the New York City Police, shortly before Christmas 1934, and at that time said he could not recall any dates upon which he saw Hauptmann in March or April 1932.” Can anyone be as certain as Kennedy claims to be that the Hauptmanns and their best friend Hans were musically trio’d when, in a cemetery not far away, the ransom was paid?

Four years after the publication of his book on the Lindbergh case, Kennedy published his memoirs, On My Way to the Club (London, 1989). Meanwhile, in 1987, a book by Jim Fisher, The Lindbergh Case, was published by Rutgers University Press (New Brunswick). Kennedy makes a chapter of his memoirs from how he came to the conclusion that Hauptmann was innocent and from what he considers most important of the things he subsequently found, so as to give ostensible support to his conclusion. And he then, in the space of a page, launches an hysterical attack on Fisher—all because, so he says, Fisher doesn’t pay enough attention to “information … used by Mrs Hauptmann’s lawyer, Tony Scaduto and myself.” It is the most despicable page of writing that I have come across in a very long while.

I hold no brief for Fisher—whom I have never met and who has written me just one letter, that in reply to a single letter I wrote to him—other than that his book is honest, any errors in it that I have noticed being slight and unintended. Which is more than can be said for some books.

I shall not comment on those parts of Kennedy’s attack on Fisher which are gratuitous, entirely irrelevant to the Lindbergh case—for I could only do so after repeating them. They should never have been published. Since Kennedy also makes a snide remark about Rutgers University Press, I shall express my surprise that his publishers, known to be reputable, permitted him to say such things.

Kennedy states, “So concerned were the New Jersey authorities by Mrs Hauptmann’s suits and the books by Tony Scaduto and myself that they gave their backing to … The Lindbergh Case.” That is untrue. Kennedy states, “The police officer in charge of the Lindbergh room at [the New Jersey] police headquarters became consultant to [Fisher’s] project.” That also is untrue. Fisher received no more help from the policeman-curator than Kennedy would have been offered if he had requested help. (Incidentally, the untrue statement is pretty rich, coming from Kennedy—who employed Anthony Scaduto’s wife as his researcher.)

Near the foot of the page, Kennedy says that, round about the time when Fisher’s book was published, he was “disappointed to hear that a [television] treatment based on my book and submitted to all three American networks had been turned down. Professionally, I was told, they all thought it a fascinating story that would make a gripping screenplay, but as network producers they did not feel they could support a programme whose conclusions were contrary to those arrived at by the American courts, and not yet reversed by them. The New Jersey establishment had triumphed again!!” Of all the many ridiculous comments made by Kennedy, that one takes the biscuit. Before writing his book, he cobbled interviews with pro-Hauptmannites into a television programme, Who Killed the Lindbergh Baby?, which was shown in Britain and America; soon afterward, a television movie based on the case, starring Anthony Hopkins as poor Bruno, was shown in both countries; in 1989, Mrs. Hauptmann and her lawyer, with other pro-Hauptmannites, appeared in a documentary that was shown throughout America.

Right to the end of The Airman and the Carpenter, Kennedy omits facts that don’t appeal to him. Apart from slight mentions in passing, none value-judgmental, all that he says about either Paul Wendel’s retracted confession or Ellis Parker is this:

[During the weekend before the execution,] there had been a new and extraordinary development in this most extraordinary of cases in that all members of the New Jersey Court of Pardons had received a twenty-five-page confession to the Lindbergh baby kidnapping and murder by a fifty-year-old disbarred Trenton attorney and convicted perjurer (who was also wanted for fraud) by the name of Paul Wendel. This was not as crazy a confession as at first thought, since it had been made to none other than Ellis Parker, Hoffman’s friend and the chief of Burlington County detectives [earlier described by Kennedy as a “brilliant investigator”]. Ellis was instructed to deliver Wendel to Mercer County detectives who took him before a Justice of the Peace to be arraigned for murder before being lodged in the Mercer County Jail. Once there he immediately repudiated the confession, claiming that he had been kidnapped by Ellis Parker and his son Ellis Junior, taken to a mental hospital for a number of days, tortured there and forced to sign the confession under duress. It seemed to many that this, if true, was a last desperate effort by Parker, convinced that Hauptmann was innocent, to save him from the chair.

That, so far as Kennedy is concerned, is, importantly, all. Any reader of his book who has not read other books on the case must be left thinking that Wendel may have committed the crimes for which Hauptmann was executed.

The continuation of the Wendel/Parker story (which Kennedy, if he had felt like it, could have recounted in his last chapter, which deals with those post-execution events which he did feel like recounting) is as follows: Wendel’s account of his being abducted and tortured into making a false confession was investigated by the district attorney of Brooklyn and proved true. Four of the gang of six confessed; one of the four died before the trial, but the others were sentenced to twenty years’ imprisonment in Sing Sing. As Governor Hoffman refused to extradite the two ring-leaders, Ellis Parker and his son, to Brooklyn, Wendel got the U.S. attorney general to agree that the charges were the concern of New Jersey’s federal grand jury, which handed down an indictment charging the Parkers with conspiracy under the Lindbergh Law (the statute, enacted in 1932, which made the kidnapping and transportation of a person across state lines punishable by imprisonment for life). Ellis Parker was sentenced to six years’ imprisonment, his son to three, in a federal penitentiary. (And so the only law enforcement officer influentially involved in the Lindbergh case whom Kennedy does not accuse of crookedness, and the only one about whom he has a nice—“brilliant”—word to say, was the only one proved to be a crook.) By using appeal procedures much as Hauptmann had done, the Parkers managed to remain at large till the summer of 1939, when they were imprisoned at Lewisburg, Pennsylvania. Early in the following year, Ellis Parker died of a brain tumour in the prison hospital; his son was released a few months later.

There is a saying that “no one suddenly becomes a murderer.” More likely to be true, it seems to me, is a saying that I have just invented: “No writer on criminal cases suddenly becomes an unreliable writer.” It would be valuable to crime historians, and others, if someone with the time and the research resources were to examine the miscarriage-of-justice books published by Kennedy before he published The Airman and the Carpenter. Let me be absolutely clear: I don’t know much about any of the cases covered, and so have no particular grounds for wondering if any of those books may have helped toward the miscarriage of justice that a guilty man was prematurely freed from imprisonment and/or pardoned and/or given compensation.

I applaud an idea mooted in the January 1988 edition of the journal of the American Academy of Forensic Sciences as a direct reaction to The Airman and the Carpenter: