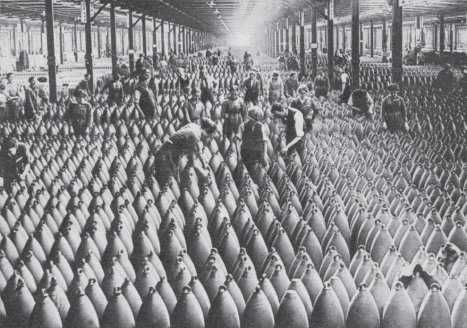

By 1917, the British ‘shell famine’ was broken. Factories like this munitions plant in Nottinghamshire produced millions of heavy rounds for a war in which artillery would inflict about 70 per cent of casualties. Women did most of the work.

THE PRINT COLLECTOR/GETTY IMAGES

The British and Empire forces detonated nineteen enormous mines before the Battle of Messines in June 1917, creating huge craters – and instant mass graves for thousands of German soldiers, the prelude to the rout of the enemy.

GALERIE BILDERWELT/GETTY IMAGES

Hundreds of thousands of Allied soldiers marched past the ruins of Ypres, on their way to the frontline. Here, men of the 1st Anzac Corps pass the wreckage of the city’s thirteenth century Cloth Hall and cathedral, in the heart of the most bombed place on the Western Front.

LT. ERNEST BROOKS/IWM VIA GETTY IMAGES

British troops preparing to attack during the Flanders Offensive. Waves upon waves would be thrown at the German lines during Third Ypres, as part of Field Marshal Sir Douglas Haig’s ‘wearing down’ war.

POPPERFOTO/GETTY IMAGES

British troops advancing through a gas cloud during Third Ypres. The Germans were the first to use mustard gas, on 12 July 1917; the Allies soon followed. The new gas was more likely to cause excruciating pain than kill you.

THE PRINT COLLECTOR/GETTY IMAGES

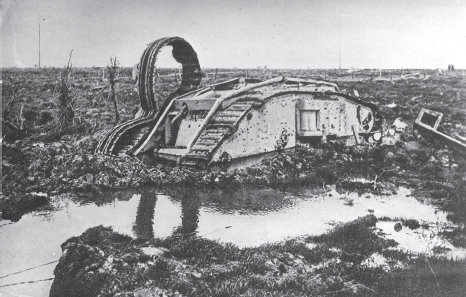

A tank graveyard in the Flanders quagmire in August 1917. Unable to advance in the hellish conditions the early tanks were easily incapacitated, and spent the remainder of the war sinking into the mud.

ULLSTEIN BILD VIA GETTY IMAGES

Bringing forward the heavy guns to protect the infantry was critical. But as the weather worsened, it proved a nightmarish struggle. Here, Allied troops heave a 15-inch ‘heavy’ into place.

POPPERFOTO/GETTY IMAGES

Australian troops wearing gas masks in an advanced trench at Garter Point, as they prepare for the Battle of Passchendaele, 27 September 1917.

IWM 205193863

‘How it happened …’ An infantryman tells his comrades of the day’s exploits, safe in their dugout for the night. Their grinning faces reveal another side to the war, the extremely close friendships of men ordered daily to risk their lives.

AWM P08577.004

Exhausted Australian troops walk along a duckboard through the remains of Chateau Wood after the Battle of Passchendaele, 29 October 1917, in which they were ordered into battle without artillery protection, with catastrophic results.

Canadian machine gunners near Passchendaele, sunk in the mud, await the final order to attack the village, which they overran in November 1917. The Canadians earned nine Victoria Crosses for the loss of 16,000 men during the final push.

PAUL POPPER/POPPERFOTO/GETTY IMAGES

Dead and wounded lie in a dugout railway bedding between Tyne Cot and Passchendaele, 12 October 1917. Photographers were often unable to distinguish the living from the dead in the groups that scattered the battlefields of Flanders.

Stretcher-bearers knee deep in mud carry a wounded soldier out of No Man’s Land. Both sides tended not to fire on stretcher parties, but showed less restraint during the final battles.

LT. J W BROOKE/IWM VIA GETTY IMAGES

Two Canadian wounded, both heavily bandaged, one with face and hands almost completely obscured, in a motor ambulance during the Battle of Passchendaele. The terrible wounds to the face and brain forged the development of modern plastic surgery and neurosurgery.

IWM 205194734

Stretcher-bearers resting behind a concrete pillbox near Zonnebeke during the fighting at Passchendaele. Stretcher teams worked in relays over the worst of the terrain. Maori bearers often did away with the stretcher and carried men out on their shoulders.

AWM E01204

In this famous photo of the battlefield the wounded are laid out at an aid post, awaiting evacuation. Rays of sunlight break through the clouds that shed torrential rain for most of August and October, turning the battlefield into a quagmire.

NATIONAL LIBRARY OF AUSTRALIA, AN24574133

Tommy and Fritz share a smoke in No Man’s Land: fraternisation was common among soldiers who grew to respect their opponents often more than their own commanders.

Prime Minister David Lloyd George would remember Passchendaele as the ‘most futile and bloody fight ever waged in the history of war’ – one that he did nothing to stop when he had the power to do so, despite his later claims.

CENTRAL PRESS/HULTON ARCHIVE/GETTY IMAGES

Field Marshal Sir Douglas Haig, the British commander-in-chief on the Western Front. During several battles of Third Ypres, he ordered his armies to attack across fields of mud, in pouring rain, knowing they faced huge losses.

CENTRAL PRESS/GETTY IMAGES

Haig meets Lloyd George, then Minister of Munitions, in France on 12 September 1916, during the Somme. Their relationship soon soured and they came to loathe each other, imperilling the Allied cause. In 1917, appalled by the losses, Lloyd George would try to transfer command of the British army to the French.

PHOTO12/UIG VIA GETTY IMAGES

Accused of being a ‘butcher’ in recent decades, Haig returned to Britain after the armistice a war hero. Hugely popular, he would devote the rest of his life to serving veterans and their families. In later years, his reputation would never recover from Passchendaele.

HARLINGUE/ROGER VIOLLET/GETTY IMAGES

General Herbert Plumer – ‘Old Plum’ – led the British and Anzacs to victory at the Battle of Messines. A champion of the ‘bite and hold’ tactics that almost broke the German lines, Plumer was reputed to be one of the better generals on the Western Front.

General Hubert Gough led the first attack of the Flanders Offensive, which ended in stalemate and his Fifth Army stalled in the mud. The Dominions would refuse to serve under him, such was his reputation for needless wastage of lives.

CHRONICLE/ALAMY STOCK PHOTO

On the agony in Flanders in 1917 German commander Erich Ludendorff, general of the infantry, would later write: ‘the horror of Verdun was surpassed … It was mere unspeakable suffering’.

HULTON ARCHIVE/GETTY IMAGES

Field Marshal Paul von Hindenburg, Kaiser Wilhelm and Ludendorff (left to right) study their maps. The war would destroy the German empire, forcing the Kaiser into exile. His most senior commanders later fell under the sway of the lance corporal turned politician, Adolf Hitler.

AWM H12326

Commander of the Anzacs, the British General William Birdwood proved popular with his men, donning the slouch hat and making an effort to understand their subversive spirit.

AWM P03717.009

The Australian General John Monash challenged his superiors’ decision to keep attacking in October 1917, when heavy rain made progress impossible. Overruled, he could do little more than reinforce his field ambulance before the attack.

CHRONICLE/ALAMY STOCK PHOTO

Fiercely protective of his men, the rotund General Sir Arthur Currie (centre), commander of the Canadian Corps, also tried to resist orders to send thousands of Canadians to certain death at Passchendaele.

CHRONICLE/ALAMY STOCK PHOTO

Theo, a friend, Keith and George Seabrook (left to right) rest before battle in Flanders, 1917. All three would die in a single action, 20–21 September. Their mother would never accept the official account of the ‘disappearance’ of George, whose body was never recovered.

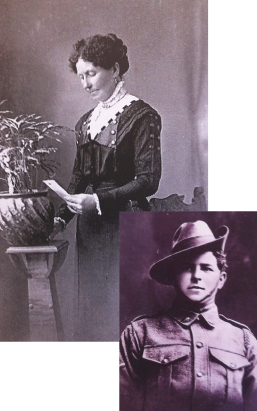

Mrs Anne Alsop, of Winchelsea, Victoria, one of thousands of mothers who received an official letter after the war, notifying her that the remains of her son, Fred (inset), twenty, were unrecoverable and that his name would be inscribed on a monument.

‘Known unto God’: here lie the remains of three unidentifiable Australian soldiers, probably blown apart by a direct hit. By the war’s end, tens of thousands of soldiers would be buried in anonymous graves.

COURTESY OF THE AUTHOR

COURTESY OF THE AUTHOR

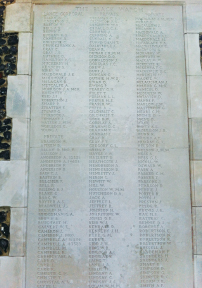

11,956 soldiers are buried at Tyne Cot, Passchendaele, the world’s largest Commonwealth cemetery (below), the walls of which bear the names of 34,857 men whose bodies were never found or identified, such as these members of the Black Watch (above).

COURTESY OF THE AUTHOR

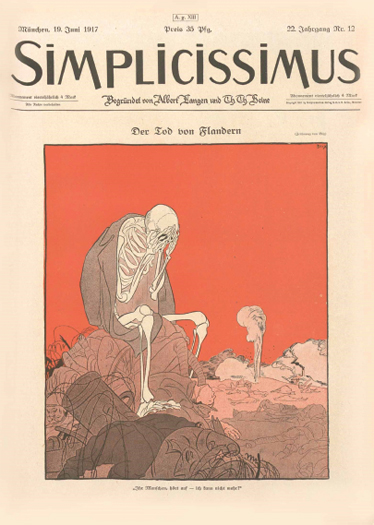

The German nation felt the terrible weight of a war that killed two million of its men. Here the Grim Reaper, on the cover of the German magazine Simplicissimus, sits on a pile of corpses in Flanders and despairs: ‘You people stop … I can’t take anymore.’