And so, with the full support of his parents, Chegwin accepted the role of owner-manager at Toffle Towers. The inheritance would be transferred into his name upon the family’s arrival at Alandale.

The Toffles decided to start packing at once. This meant wrapping things up quickly at Chegwin’s school. His final day there, however, was not a particularly pleasant occasion. Mr Bridges made sure of it.

‘Tuck in your shirt, Toffle!’ snapped the teacher. ‘We are about to embark on a three-hour study of brick density and you must be ready to focus.’

Chegwin was wearing his favourite blue-striped, button-up shirt, which was not only untucked on one side, but fastened skewiff. You could learn a lot about someone by the way they reacted to your shirt, thought Chegwin. If a person’s left eye twitched at the sight of an extra buttonhole, he figured that person was the sort worth avoiding. If someone thought nothing of the way he dressed, well, that was the sort of person he’d like to be friends with.

Not that Chegwin was very good at making friends. Truth be told, he had never really had any. As much as he tried to be nice at school, his peers preferred to keep their relationship distant. After all, nobody wants to be seen with the teacher’s punching bag. Perception is a powerful thing.

The only person at school that Chegwin had taken a liking to was old Mrs Flibbernut, who occasionally filled in for Mr Bridges when he was away at meat pie eating competitions. Mrs Flibbernut’s lessons were both theatrical and logical. Chegwin found it awfully difficult to drift off when she explained things such as the life cycle of a frog. Her leg kicks were quite believable, and once she even managed to catch a fly with her tongue. But best of all, she never mentioned anything about Chegwin’s shirt.

Mr Bridges’ left eye was twitching now. ‘I’m glad you’re leaving, Toffle. We all are. This class will be brighter for your absence.’

‘Where’s he going, Mr Bridges?’ asked Ralph, preferring to address the teacher rather than Chegwin.

‘Alandale,’ said Mr Bridges. ‘I pity the people there as they’re about to inherit a dillydallying dreamer.’

Fortunately, Chegwin didn’t hear that last comment. He had managed to distract himself by wondering what the life of an aardvark would be like if it could fly.

Sienna raised her hand. ‘My cousin visited Alandale last year to watch the Great River Race.’

‘Soon they’ll have the Great River Nutcase,’ said Mr Bridges.

This triggered a flurry of cruel remarks.

‘I wish you’d leave right now, Chegwin.’

‘School will be so much better without you.’

‘I hope you fall into the river.’

‘Don’t be mean … Rivers shouldn’t have to put up with ninnies like him.’

‘Nice one, Justin.’

‘Thanks, Ruby.’

Chegwin tuned back in and caught the last of the comments. A sick feeling churned in his stomach – as it often did when he was being made fun of – and he mumbled an apology to no one in particular. Why was everyone so mean to him when he drifted off in thought? He wished more people were patient like his parents.

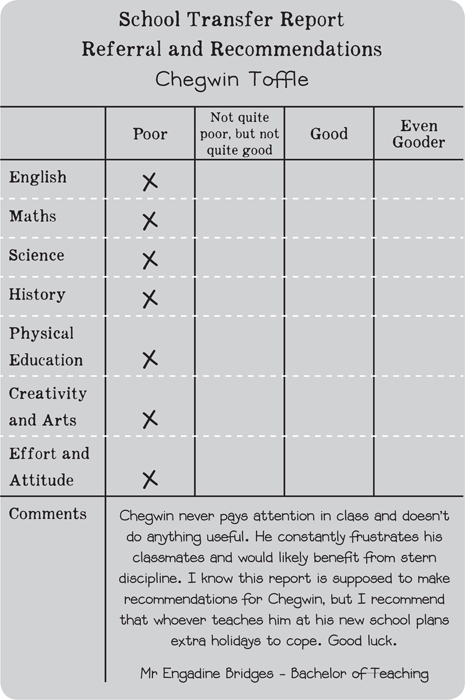

If Chegwin had not been required to collect his ‘Referral and Recommendations’ report from school, he would have chosen to stay home and keep packing for Alandale. But as it stood, he had to endure one last day of insults.

Just before the final bell, Mr Bridges’ flabby fingers dropped a piece of paper on Chegwin’s desk. ‘I think you’ll find this is a fair summary of your learning here with us.’

Chegwin scanned the report.

The bell rang and everyone hooted and cheered – not in celebration of the end of the day, but in recognition that Chegwin was leaving for good.

Chegwin cleared out his desk – much to the delight of Mr Bridges, who had pulled up a seat to watch and was eating popcorn – and put on his backpack. He waved goodbye and left school for the last time.

The walk home was strangely uplifting for Chegwin. It signalled the beginning of something new. Something unexpected. He was about to take charge of a grand hotel and it was the most important thing he’d ever had to do. There were people working at Toffle Towers who were relying on him to keep it running.

His parents had discussed the importance of finding him a new school once they arrived in Alandale. Being a remote tourist town, he would likely have to travel some distance by bus. This intrigued Chegwin. Where would he have to commute to? What would his new teacher be like? How would he juggle homework and managing a hotel? And most importantly, would he be able to make any friends?

Although feeling positive about the change, Chegwin sighed. The logical side of his brain told him that a new location would not likely change his experience of school.

The sight of Mrs Flibbernut’s white picket fence suddenly gave him an idea.

Chegwin stopped and selected a marigold for his mother. Then he retrieved some blank paper and a pencil from his backpack and wrote Mrs Flibbernut a letter. When he was finished, he slipped the note and some money for the flower into the old lady’s letterbox. He had just made his first decision as manager of Toffle Towers.

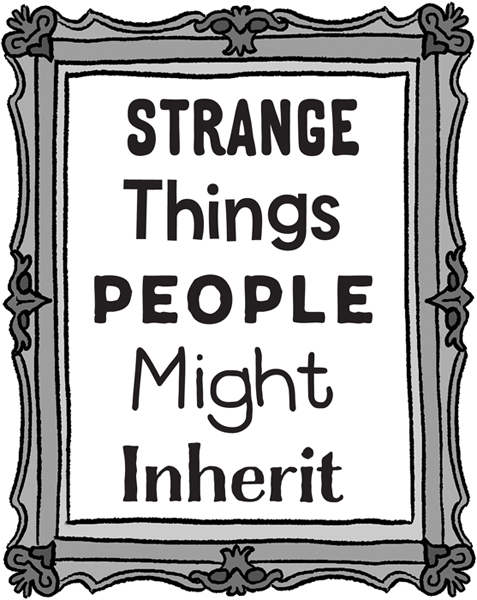

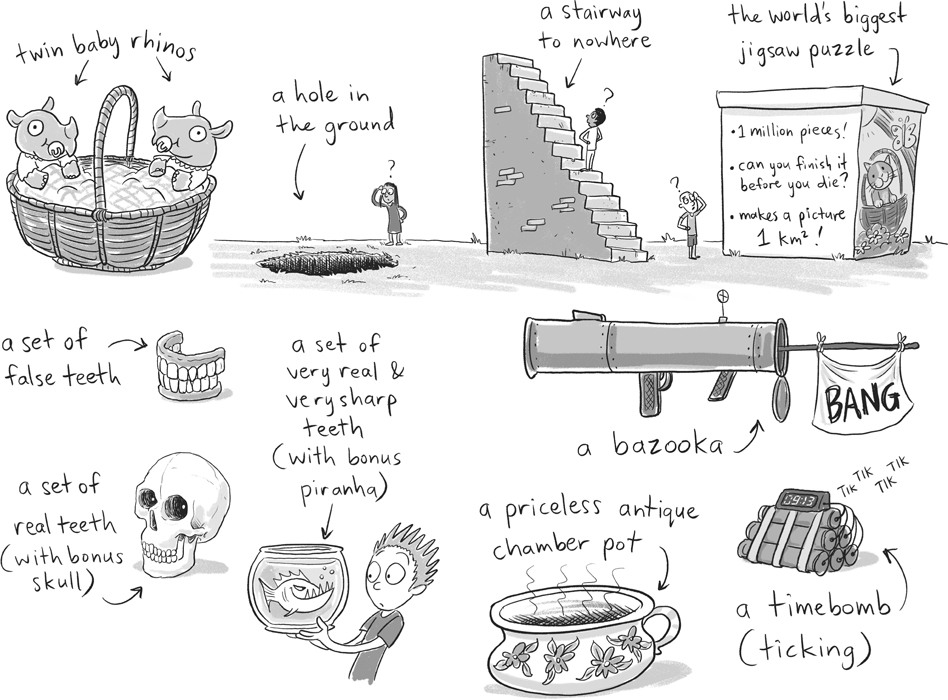

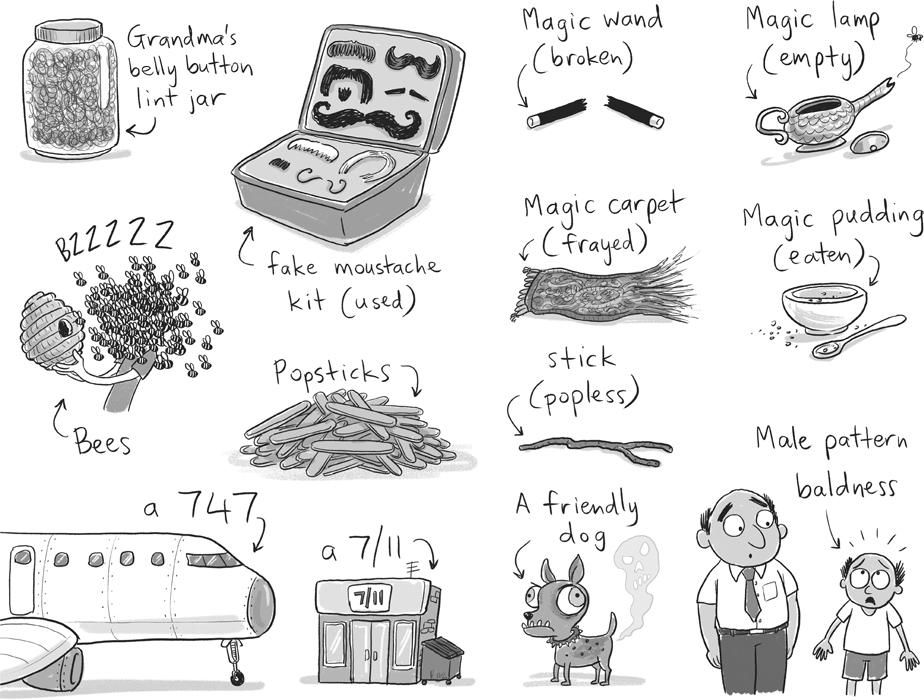

Feeling on top of the world, the rest of the walk home was the stuff dreams were made of. Literally. Knowing that in a matter of days he would be saving jobs in Alandale – and far away from Mr Bridges to boot – Chegwin set loose the imaginative side of his brain. He wondered what other strange things people might inherit.