Chapter 2: The Murder Casebook

In defiance of the overcast skies, many middle-class Londoners made the most of August Bank Holiday Monday, 1888, by taking day trips to the south coast or excursions into the countryside. Those who chose to remain in the capital were spoilt for choice as to how to pass the day. Almost all the customary attractions were within a short omnibus ride of the West End and were still a novelty. For half a crown a family of four could spend an agreeable afternoon gaping at the animals in the Zoological Gardens in Regent’s Park, marvelling at the lifelike figures at Madame Tussaud’s or taking in a tour at the Tower of London and still have change for refreshments and the ride home. A couple of shillings would cover entrance to the exotic orchid houses at Crystal Palace or the manicured gardens at Kew, while edification and culture could be had for free at the Natural History Museum and Science Museum in fashionable Kensington or at the National Portrait Gallery, which relocated from South Kensington to Bethnal Green in 1885. The advantage of museums was that they offered both diversion and shelter should the skies open unexpectedly.

In contrast, many of those living south of the river enjoyed the day in a more modest manner. Martha Tabram (aka Martha Turner) and her friend Pearly Poll spent the day cadging drinks in various public houses around Whitechapel. Martha, who for some reason had told her new friend that her name was ‘Emma’, was a plump, 39-year-old married mother of two teenage sons, with a swarthy complexion. She had been separated from her husband Henry, a foreman furniture packer, for nine years and had been living with William Turner, a carpenter, in George Street, Whitechapel, supplementing their income by hawking trinkets for a halfpenny an item. But her fondness for ale, and anything stronger when she could afford it, had led her to rely on prostitution. Turner had given up on her and Martha was in need of a few coppers for a room. Poll’s offer to team up for the night must have seemed like a practical solution.

By 10pm they had befriended two soldiers at the Angel and Crown, who said they were stationed at the Tower of London, and were confident of procuring enough change to pay for their lodgings. Shortly before midnight the pair separated. Polly led her client into nearby Angel Alley and Martha staggered arm in arm with her customer round the corner to George Yard, off Whitechapel High Street. Half an hour later Polly and her punter bid each other goodnight and she wandered off giving no further thought to her friend.

A body discovered

It was not until 4.45am the next morning that John Reaves, a tenant at 37 George Yard Buildings, came upon the lifeless body of a woman sprawled on the first-floor landing as he made his way to work. It was Martha Tabram. She was lying on her back with her legs apart and her long black jacket, dark green skirt and brown petticoat pushed up to the waist, suggesting that she had been killed while engaged in intercourse. Her fists were clenched in her death agony and thick sticky blood pooled around her on the flagstones from her black bonnet to her side-spring boots. Reaves stepped over the body and legged it down the stairs and out into the street in search of a policeman.

Under the headline ‘The Murder in Whitechapel’, the following extract from The Times, dated 10 August 1888, details what Dr Killeen, a local physician, discovered when he was called to the scene that morning. The fact that the murder went unreported for three days suggests that both the press and the police were slow to realize the significance of the Martha Tabram murder.

‘Dr T R Killeen, of 68, Brick-lane, said that he was called to the deceased, and found her dead. She had 39 stabs on the body. She had been dead some three hours. Her age was about 36, and the body was very well nourished. Witness had since made a post mortem examination of the body. The left lung was penetrated in five places, and the right lung was penetrated in two places. The heart, which was rather fatty, was penetrated in one place, and that would be sufficient to cause death. The liver was healthy, but was penetrated in five places, the spleen was penetrated in two places, and the stomach, which was perfectly healthy, was penetrated in six places. The witness did not think all the wounds were inflicted with the same instrument. The wounds generally might have been inflicted with a knife, but such an instrument could not have inflicted one of the wounds, which went through the chestbone. His opinion was that one of the wounds was inflicted by some kind of dagger, and that all of them had been caused during life. The Coroner [remarked that]…it was one of the most dreadful murders any one could imagine. The man must have been a perfect savage to inflict such a number of wounds on a defenceless woman in such a way.’

It was established that Martha had been murdered between 1.50 and 3.30am. At the coroner’s inquest, resident Elizabeth Mahonney had testified that she had returned at 1.50 to her rooms at 47 George Yard and seen no one on the landing. An hour and 40 minutes later cab driver Alfred Crow ascended the wide stone staircase to his rooms at number 35 and noticed a woman lying on the landing, but thought little of it as vagrants were in the habit of sleeping off their drink at George Yard. None of the residents had heard a sound during the night, although Mrs Hewitt, the building superintendent’s wife, had heard a cry of ‘murder’ earlier that evening, but hadn’t informed her husband as it appeared to originate from outside and such disturbances were an almost nightly occurrence in the area.

The reason no one heard the poor woman’s cry for help was addressed by the Illustrated Police News, a sensationalist tabloid which, despite the title, had no association with the authorities. It speculated that her cries had been stifled. She had been ‘throttled while being held down and the face and head being so swollen and distorted in consequence that her real features are not discernible’. The Daily News added that Dr Killeen had concluded that there may have been two assailants, one evidently left-handed and the other right-handed and that the wounds had been inflicted by two weapons, one a penknife and the other either a dagger or bayonet.

A soldier under suspicion

Suspicion immediately fell on the soldier who appeared to have been the last person to have seen Martha alive. PC Barrett, the officer who had been called to the scene by Reaves, had seen a soldier loitering in George Yard at 2am, at the time the murder might have occurred. It is very likely that this was the same soldier Martha had been keeping company with two hours earlier when she parted with Pearly Poll. When PC Barrett approached him and asked what he was doing at this hour the soldier replied that he was waiting for a friend who had gone with a woman.

PC Barrett described the soldier as a private in the Grenadier Guards who had a good conduct badge pinned to his tunic but no medals. He was in his early to mid-twenties, of average height (about 175cm/5ft 9in) with a fair complexion, dark hair and a small brown moustache turned up at the ends. But when an identification parade was arranged at the Tower on the morning of 8 August, the constable picked out two men who verified each other’s story and were allowed to return to the ranks. That may have been Scotland Yard’s first fatal mistake. The soldiers were almost certainly the killers and, had they been questioned more thoroughly, Martha Tabram might not be acknowledged today as the Ripper’s first victim.

The body in Bucks Row

Fate was particularly cruel to Mary Ann ‘Polly’ Nichols. She should have been safe in bed on the morning of 31 August 1888 but was instead found sprawled in the street gutted like one of the pigs in nearby Spitalfields market. She had earned her bed and board three times that day but had drunk it all away. Had she saved just a few coppers, she would not have been soliciting for her final customer of the evening when she fell foul of Jack the Ripper.

Polly Nichols was a short, stout, middle-aged, married woman with five children who had been separated from her family because of her fondness for alcohol and was forced to rely on the charitable ministrations of Lambeth Workhouse. But shortly before her death she had tried to get back on the straight and narrow by taking a position as a domestic servant to a respectable couple in Wandsworth. Her new-found employment enabled her to leave the workhouse and find lodgings at Thrawl Street with an elderly room-mate who described her as clean, quiet and inoffensive, so long as she was sober. Her new employers evidently found her agreeable too and something of her state of mind at the time can be gleaned from her final letter to her estranged husband, which paints a very different picture of a penniless streetwalker to the blowsy, foul-mouthed bawd of popular fiction.

‘I just write to say that you will be glad to know that I am settled in my new place and going on all right up to now. My people went out yesterday, and have not returned, so I am left in charge. All has been newly done up. They are teetotallers and religious, so I ought to get on. They are very nice people, and I have not too much to do. I hope you are alright and the boy has work. So good-bye for the present. –

From yours truly POLLY

Answer soon, please, and let me know how you are.’

A fatal error

However, the demon drink bedevilled Polly and during a moment of weakness she gave in to temptation, stealing a bundle of clothes from her employers for which she was summarily dismissed. On the night of her death she was turned away from her old lodgings in Thrawl Street because she didn’t have the 4d for the room. Undaunted, she told them to hold her bed for her and that she would be back shortly with the money.

‘I’ll soon get my doss money,’ she laughed as she staggered down the street. ‘See what a jolly bonnet I’ve got now!’

Polly was proud of her new black straw bonnet with the black trim. Beneath it her brown hair was turning prematurely grey, framing her sallow skin and brown eyes. She wore a rustic brown, double-breasted overcoat, a new frock of the same colour, a white chest flannel, black stockings and side-spring boots with steel-tipped heels to save wear and tear.

At the corner of Whitechapel Road and Osborn Street she chanced to meet her former room-mate, Ellen Holland, who vainly tried to persuade Polly to come back with her. ‘I’ve had my lodging money three times today and I’ve spent it,’ Polly boasted. ‘It won’t be long before I’ll be back.’ It was 2.30am when they parted. Ellen was the last person to see Polly alive.

Just over an hour later two workmen walking down the narrow north end of Bucks Row towards the Board School where the street widens came upon what they assumed to be a tarpaulin discarded on the pavement by the entrance to Brown’s Stable Yard. In the early-morning gloom, with only a feeble street lamp across the way, they couldn’t make out what it was until they stood over it. It was the body of a woman lying on her back with her skirts up around her waist. They adjusted them to afford her some dignity before summoning a policeman, PC Mizen. ‘She looks to me to be either dead or drunk,’ said one, urging the constable to investigate. ‘But for my part I think she is dead.’ Meanwhile, another policeman, PC Neil, stumbled upon the body and was shortly joined by the two workmen and PC Mizen.

She was indeed dead, although no one realized the extent of her mutilations until she had been removed to the mortuary for closer examination. In the early-morning light all the police knew was that her throat had been cut so violently that her head had been almost severed from her body. Her eyes were wide open, gazing up at the blood-red sky. When the horse-drawn ambulance came to take her away her new black bonnet was tossed into the cart beside her.

Polly Nichols, who was murdered on 31 August 1888, was found sprawled in the street, gutted like a pig

The Whitechapel murders

The following extract from The Times, 3 September 1888, is of special interest as it is the first indication that the police were considering that the murders might be the work of a serial killer. It also highlights the question of how the Ripper managed to elude a strong police presence in the area.

‘Up to a late hour last evening the police had obtained no clue to the perpetrator of the latest of the three murders which have so recently taken place in Whitechapel, and there is, it must be acknowledged, after their exhaustive investigation of the facts, no ground for blaming the officers in charge should they fail in unravelling the mystery surrounding the crime. The murder, in the early hours of Friday morning last, of the woman now known as Mary Ann Nichols, has so many points of similarity with the murder of two other women in the same neighbourhood – one Martha Tabram, as recently as August 7, and the other less than 12 months previously – that the police admit their belief that the three crimes are the work of one individual. All three women were of the class called “unfortunates,” each so very poor, that robbery could have formed no motive for the crime, and each was murdered in such a similar fashion, that doubt as to the crime being the work of one and the same villain almost vanishes, particularly when it is remembered that all three murders were committed within a distance of 300 yards from each other.

These facts have led the police to almost abandon the idea of a gang being abroad to wreak vengeance on women of this class for not supplying them with money. Detective Inspector Abberline, of the Criminal Investigation Department, and Detective Inspector Helson, J Division, are both of opinion that only one person, and that a man, had a hand in the latest murder. It is understood that the investigation into the George-yard mystery is proceeding hand-in-hand with that of Bucks Row. It is considered unlikely that the woman could have entered a house, been murdered, and removed to Bucks Row within a period of one hour and a quarter. The woman who last saw her alive, and whose name is Nelly Holland, was a fellow-lodger with the deceased in Thrawl Street, and is positive as to the time being 2:30. Police constable Neil, 79 J, who found the body, reports the time as 3:45. Bucks Row is a secluded place, from having tenements on one side only. The constable has been severely questioned as to his “working” of his “beat” on that night, and states that he was last on the spot where he found the body not more than half an hour previously – that is to say, at 3:15.

The beat is a very short one, and quickly walked over would not occupy more than 12 minutes. He neither heard a cry nor saw any one. Moreover, there are three watchmen on duty at night close to the spot, and neither one heard a cry to cause alarm. It is not true, says Constable Neil, who is a man of nearly 20 years’ service, that he was called to the body by two men. He came upon it as he walked, and flashing his lantern to examine it, he was answered by the lights from two other constables at either end of the street. These officers had seen no man leaving the spot to attract attention, and the mystery is most complete . . .

The deceased was lying lengthways, and her left hand touched the gate. With the aid of his lamp he examined the body and saw blood oozing from a wound in the throat. Deceased was lying upon her back with her clothes disarranged. Witness felt her arm, which was quite warm from the joints upwards, while her eyes were wide open. Her bonnet was off her head and was lying by her right side, close by the left hand. Witness then heard a constable passing Brady Street, and he called to him. Witness said to him, “Run at once for Dr. Llewellyn.” Seeing another constable in Baker’s Row, witness despatched him for the ambulance . . .

[PC Neil] had not heard any disturbance that night. The farthest he had been that night was up Baker’s Row to the Whitechapel Road, and was never far away from the spot. The Whitechapel Road was a busy thoroughfare in the early morning, and he saw a number of women in that road, apparently on their way home. At that time any one could have got away. Witness examined the ground while the doctor was being sent for. In answer to a juryman, the witness said he did not see any trap in the road. He examined the road, but could not see any marks of wheels . . .

Mr. Henry Llewellyn, surgeon, of 152, Whitechapel Road, stated that at 4 o’clock on Friday morning he was called by the last witness to Bucks Row . . . On reaching Bucks Row he found deceased lying flat on her back on the pathway, her legs being extended. Deceased was quite dead, and she had severe injuries to her throat. Her hands and wrists were cold, but the lower extremities were quite warm . . . He should say the deceased had not been dead more than half an hour . . . There was very little blood round the neck, and there were no marks of any struggle, or of blood as though the body had been dragged . . . That morning he made a post mortem examination of the body.

It was that of a female of about 40 or 45 years. Five of the teeth were missing, and there was a slight laceration of the tongue. There was a bruise running along the lower part of the jaw on the right side of the face. That might have been caused by a blow from a fist or pressure from a thumb. There was a circular bruise on the left side of the face, which also might have been inflicted by the pressure of the fingers. On the left side of the neck, about 1in. below the jaw, there was an incision about 4in. in length, and ran from a point immediately below the ear. On the same side, but an inch below, and commencing about 1in. in front of it, was a circular incision, which terminated in a point about 3in. below the right jaw. That incision completely severed all the tissues down to the vertebrae. The large vessels of the neck on both sides were severed. The incision was about 8in. in length. The cuts must have been caused by a long-bladed knife, moderately sharp, and used with great violence.

No blood was found on the breast, either of the body or clothes. There were no injuries about the body until just below the lower part of the abdomen. Two or three inches from the left side was a wound running in a jagged manner. The wound was a very deep one, and the tissues were cut through. There were several incisions running across the abdomen. There were also three or four similar cuts, running downwards, on the right side, all of which had been caused by a knife which had been used violently and downwards. The injuries were from left to right, and might have been done by a left-handed person. All the injuries had been caused by the same instrument.’

Bloodhounds

Shortly before Christmas 1887, Detective Inspector Frederick George Abberline had been honoured with a presentation dinner at the Unicorn Tavern in Shoreditch to commemorate his 25 years’ service in the Metropolitan Police, the past 14 of which he had spent in the East End. It was a grand affair with effusive speeches, good food and plenty of locally brewed beer, at the end of which the modest and meticulous West Country career policeman was presented with a gold watch by a grateful citizens’ committee and his many colleagues at H Division in recognition of his contribution to keeping a cap on crime in the roughest district in London. Abberline, who was by then 45 years old, was looking forward to taking up his new post at Scotland Yard to which he had been seconded at the request of the top brass at the newly formed Criminal Investigation Division, or CID as it became known. He could not have imagined that within a year he would be called back to Whitechapel to lead the hunt for a multiple murderer who would ultimately elude both himself and the most experienced detectives in the country.

Abberline knew all the shady characters in every back street of the East End and he didn’t attain such knowledge sitting behind his desk. But when he returned to his old hunting ground in the autumn of 1888 he was portly and balding, with a soft-spoken manner no self-respecting villain would have found intimidating. Colleague Walter Dew (another member of the Ripper team) thought he looked more like a bank manager or solicitor, but Abberline was a copper of the old school, a human bloodhound who wouldn’t give up on a trail once he’d got the scent. If anyone could catch the Whitechapel murderer he could.

A dangerous labyrinth

Abberline was initially optimistic about catching the man responsible for the deaths of Martha Tabram and Polly Nichols. But it soon became clear that the quarry knew the labyrinth of alleyways in even more detail than he did. The scale of the problem can be gleaned from a contemporary account written by American journalist R. Harding Davis, who was taken on a tour of the murder sites by another member of Abberline’s team, Inspector Henry Moore.

Moore cut a formidable figure in the East End. He was muscular and evidently able to handle himself, but even so he carried a maple-coloured cane of solid iron in anticipation of trouble, ‘for those who don’t know me’. He told Davis:

‘I might put two regiments of police in this half-mile of district and half of them would be as completely out of sight and hearing of the others as though they were in separate cells of a prison. To give you an idea of it, my men formed a circle around the spot where one of the murders took place, guarding, they thought, every entrance and approach, and within a few minutes they found fifty people inside the lines. They had come in through two passageways which my men could not find. And then, you know, these people never lock their doors, and the murderer has only to lift the latch of the nearest house and walk through it and out the back way . . .

‘What makes it so easy for him is that the women lead him of their own free will to the spot where they know interruption is least likely. It is not as if he had to wait for his chance; they make the chance for him. And then they are so miserable and so hopeless, so utterly lost to all that makes a person want to live, that for the sake of four pence, enough to get drunk on, they will go in any man’s company, and run the risk that it is not him. I tell many of them to go home, but they say that they have no home, and when I try to frighten them and speak of the danger they run, they’ll laugh and say, “Oh, I know what you mean. I ain’t afraid of him. It’s the Ripper or the bridge for me [meaning suicide]. What’s the odds?” and it’s true; that’s the worst of it.’

It was customary for Scotland Yard to send experienced men to assist the local police when their resources were stretched during a serious investigation. So it was not considered a sign of impatience or lack of confidence in local Inspector Edmund Reid and his men when Chief Inspector Moore and his two colleagues, inspectors Abberline and Andrews, arrived at the Commercial Street police station in Whitechapel with a number of assistants in tow, one of them being Detective Walter Dew, who was later to find fame as the man who arrested Dr Crippen. Their arrival was intended to signal that the investigation was to be stepped up a gear and it also served to repair the damage done to morale by the recent resignation of Assistant Commissioner James Monro, who had quarrelled with his superior, Sir Charles Warren. Monro’s replacement was to be Dr Robert Anderson, but ill health prevented Anderson from taking up his post before the beginning of October so Moore, Abberline and Andrews were effectively in charge of the manhunt under the supervision of Chief Inspector Donald Swanson back at Scotland Yard.

Of the three Yard men sent down to Commercial Street, the most overlooked is Inspector Walter Andrews, who had been described by Dew as a ‘jovial, gentlemanly man’. He was 41 years of age when he was assigned to the Ripper case and, though he is not featured at all in the official records, it is believed that it is because he was on the trail of one particular individual, a previously unnamed suspect whose file mysteriously went missing from the archives.

As Walter Dew was later to note in his memoirs, ‘There are still those who look upon the Whitechapel murders as one of the most ignominious police failures of all time. Failure it certainly was, but I have never regarded it other than an honourable failure.’

And he defended the reputations of the three CID detectives sent to assist the local officers. ‘I am satisfied that no better or more efficient men could have been chosen. These three men did everything humanly possible to free Whitechapel of its Terror. They failed because they were up against a problem the like of which the world had never known, and I fervently hope, will never know again.’

Horrible murder in Hanbury Street

‘Dark Annie’ Chapman was a short, heavy-set woman who had lived most of her life on the streets of the East End. Never an attractive woman, by the time she had turned 45 she looked as if life had knocked her about a bit and she had the bruises to prove it. The first of her three children had died, the second had been institutionalized and the third confined in a home for cripples. Her husband had reputedly drunk himself to death and Annie looked set to follow him. By September 1888 she was destitute and down to borrowing a couple of shillings from her brother to pay for a cheap room and a meal with the promise to pay him back when she went hop-picking in Kent. But as always, it was just talk. She never left the city.

In the early hours of Saturday 8 September 1888 she was turned away from her lodgings at 35 Dorset Street because she didn’t have the necessary 4d for a bed and tottered down nearby Hanbury Street in search of a customer. Some time between 5.30 and 6am she became yet another victim of Jack the Ripper.

Body in a back yard

Her body was discovered in the back yard of number 29 Hanbury Street, Spitalfields, by an elderly resident who immediately ran for help. Inspector Joseph Chandler was summoned from Commercial Street police station and was the first officer to examine the body, together with police surgeon Dr George Bagster Phillips. Both had seen their share of violent murders but neither was prepared for the gratuitous mutilations in evidence that morning.

The final resting place of Annie Chapman

While neighbours leaned out of their rear windows overlooking the yard, Dr Phillips made an initial examination to determine the time and cause of death. Annie was lying on her back along the fence with her head a few centimetres from the bottom step leading from the back door into the yard. Her blood-smeared hands had stiffened in her death agony as if clutching at her throat, which was wrapped in a handkerchief that the killer might have used to stem the flow of blood, and her legs were drawn up as if she had been having sex when she was killed. The throat had been severed by a ragged cut and the small intestine had been removed and thrown over the right shoulder. Two more portions of the belly wall had been peeled back over the left shoulder and the belly wall with the navel, the womb, the uterus and a portion of the bladder had been removed. Dr Phillips was of the opinion that the killer had a rudimentary grasp of anatomy and that he had used a narrow-bladed knife of 15–20cm (6–8in) in length such as a slaughterman might use – or a surgeon specializing in amputation.

A gruesome search

A search of the yard yielded what appeared to be a number of significant clues, the most promising of which was a wet leather apron hanging a few feet from a dripping tap which it was thought might have been used by the murderer to protect his clothes from being spattered with blood. But inquiries determined that it belonged to the son of one of the residents who had washed it and left it to dry a couple of days earlier. Similarly, a portion of an envelope bearing the seal of the Sussex Regiment and the letters ‘M’ and ‘Sp’ looked promising. The envelope contained pills and was postmarked ‘London, August 23’. But it too proved a false lead. Witnesses had seen Annie pick up a discarded envelope from the floor of her lodging house which answered the description of the portion found near the body and the pills had been hers.

Perhaps the most curious detail was that her paltry personal possessions – a toothbrush and comb – had been placed on a piece of muslin and neatly arranged at her feet as if part of a bizarre ritual. Or perhaps they had been placed there merely to taunt the police? And then there was the matter of the missing rings. The abrasions on her fingers suggested that they had been wrenched off violently, yet both were clearly imitation gold and worth no more than a few shillings. A thorough search of the local pawn shops failed to locate them. The only possible explanation is that they had been taken by the killer as souvenirs of the kill.

The inhabitants of number 29 and their neighbours wasted no time in exploiting the commercial potential of their location. Even after the body had been taken away they were still charging a penny to view the murder site from their back windows.

In a subsequent editorial The Times speculated:

‘Intelligent observers who have visited the locality express the utmost astonishment that the murderer could have reached a hiding place after committing such a crime. He must have left the yard in Hanbury Street reeking with blood, and yet, if the theory that the murder took place between 5 and 6 be accepted, he must have walked in almost broad daylight along streets comparatively well frequented, even at that early hour, without his startling appearance attracting the slightest attention. Consideration of this point has led many to the conclusion that the murderer came not from the wretched class from which the inmates of common lodging-houses are drawn. More probably, it is argued, he is a man lodging in a comparatively decent house in the district, to which he would be able to retire quickly, and in which, once it was reached, he would be able at his leisure to remove from his person all traces of his hideous crime . . . The murderer must have known the neighbourhood, which is provided with no fewer than four police stations, and is well watched nightly, on account of the character of many of the inhabitants.’

Inquest into the death of Annie Chapman

The full extent of the Ripper’s rudimentary surgical skills can best be gleaned from evidence given at the inquest into the death of Annie Chapman by Dr George Bagster Phillips, the divisional surgeon of police.

‘Dr Phillips: I found the body of the deceased lying in the yard on her back. The face was swollen and turned on the right side, and the tongue protruded between the front teeth, but not beyond the lips; it was much swollen. The small intestines and other portions were lying on the right side of the body on the ground above the right shoulder, but attached. There was a large quantity of blood, with a part of the stomach above the left shoulder.

The throat was dissevered deeply. I noticed that the incision of the skin was jagged, and reached right round the neck. On the back wall of the house, between the steps and the palings, on the left side, about 18in from the ground, there were about six patches of blood, varying in size from a sixpenny piece to a small point, and on the wooden fence there were smears of blood, corresponding to where the head of the deceased laid, and immediately above the part where the blood had mainly flowed from the neck, which was well clotted.

The incisions of the skin indicated that they had been made from the left side of the neck on a line with the angle of the jaw, carried entirely round and again in front of the neck, and ending at a point about midway between the jaw and the sternum or breast bone on the right hand. There were two distinct clean cuts on the body of the vertebrae on the left side of the spine. They were parallel to each other, and separated by about half an inch. The muscular structures between the side processes of bone of the vertebrae had an appearance as if an attempt had been made to separate the bones of the neck. There are various other mutilations of the body, but I am of opinion that they occurred subsequently to the death of the woman and to the large escape of blood from the neck.

Coroner: Was there any anatomical knowledge displayed?

Dr Phillips: I think there was. There were indications of it. My own impression is that that anatomical knowledge was only less displayed or indicated in consequence of haste. The person evidently was hindered from making a more complete dissection in consequence of the haste.

Coroner: Was the whole of the body there?

Dr Phillips: No; the absent portions being from the abdomen.

Coroner: Are those portions such as would require anatomical knowledge to extract?

Dr Phillips: I think the mode in which they were extracted did show some anatomical knowledge.

Coroner: In your opinion did she enter the yard alive?

Dr Phillips: I am positive of it. I made a thorough search of the passage, and I saw no trace of blood, which must have been visible had she been taken into the yard. I am of opinion that the person who cut the deceased’s throat took hold of her by the chin, and then commenced the incision from left to right.

Coroner: Could that be done so instantaneously that a person could not cry out?

Dr Phillips: By pressure on the throat no doubt it would be possible.

Coroner: Can you give any idea how long it would take to perform the incisions found on the body?

Dr Phillips: I think I can guide you by saying that I myself could not have performed all the injuries I saw on that woman, and effect them, even without a struggle, under a quarter of an hour. If I had done it in a deliberate way, such as would fall to the duties of a surgeon, it would probably have taken me the best part of an hour. The whole inference seems to me that the operation was performed to enable the perpetrator to obtain possession of these parts of the body.’

Leather Apron

On 4 September the national newspapers revealed that the police were hunting a vile individual known locally as Leather Apron. He had been brought to the attention of the authorities because of his reputation for violent assaults upon prostitutes in the area whom he would threaten with a knife, and if they did not pay him he would beat them until they promised to do so.

His real name was John Pizer but he acquired his nickname from the leather apron he had worn while working as a slipper-maker and which he continued to wear even after he found that extortion was more lucrative.

As soon as Pizer learned that he was being sought in connection with the Whitechapel killings he made himself scarce and it took the police a week to track him down to a relative’s house at 22 Mulberry Street.

On 11 September The Times reported his arrest, the first in what proved to be a series of false leads that plagued the investigation from the first.

‘Yesterday morning Detective Sergeant Thicke, of the H Division, who has been indefatigable in his inquiries respecting the murder of Annie Chapman at 29, Hanbury Street, Spitalfields, on Saturday morning, succeeded in capturing a man whom he believed to be “Leather Apron.” It will be recollected that this person obtained an evil notoriety during the inquiries respecting this and the recent murders committed in Whitechapel, owing to the startling reports that had been freely circulated by many of the women living in the district as to outrages alleged to have been committed by him . . .

Shortly after 8 o’clock yesterday morning Sergeant Thicke, accompanied by two or three other officers, proceeded to 22, Mulberry Street and knocked at the door. It was opened by a Polish Jew named Pizer, supposed to be “Leather Apron.” Thicke at once took hold of the man, saying, “You are just the man I want.” He then charged Pizer with being concerned in the murder of the woman Chapman, and to this he made no reply. The accused man, who is a boot finisher by trade, was then handed over to other officers and the house was searched. Thicke took possession of five sharp long-bladed knives – which, however, are used by men in Pizer’s trade – and also several old hats. With reference to the latter, several women who stated they were acquainted with the prisoner, alleged he has been in the habit of wearing different hats. Pizer, who is about 33, was then quietly removed to the Leman Street Police station, his friends protesting that he knew nothing of the affair, that he had not been out of the house since Thursday night, and is of a very delicate constitution. The friends of the man were subjected to a close questioning by the police. It was still uncertain, late last night, whether this man remained in custody or had been liberated. He strongly denies that he is known by the name of “Leather Apron.”’

Pizer had an alibi for the night Polly Nichols was murdered. He claimed to have been in a lodging house in Holloway Road and his statement was subsequently confirmed by the owner.

When Annie Chapman was killed he was in hiding at his brother’s house. Nevertheless, he was kept in a cell overnight and included in an identification parade the following day. The only witness was a tramp who swore that Pizer was the man he had seen threatening a woman on the night of the Nichols murder, but on closer questioning the witness proved unreliable and Pizer was released.

Pizer was ordered to appear before the inquest into the death of Annie Chapman to account for his movements on the night in question and this gave the press their first look at one of Whitechapel’s most unsavoury characters. The East London Observer described him in Dickensian terms:

‘He was a man of about five feet four inches, with a dark-hued face, which was not altogether pleasant to look upon by reason of the grizzly black strips of hair, nearly an inch in length, which almost covered the face. The thin lips, too, had a cruel, sardonic kind of look, which was increased, if anything, by the drooping dark moustache and side whiskers. His hair was short, smooth, and dark, intermingled with grey, and his head was slightly bald on the top. The head was large, and was fixed to the body by a thick heavy-looking neck. Pizer wore a dark overcoat, brown trousers, and a brown and very much battered hat, and appeared somewhat splay-footed.

When Baxter [the Coroner] asked Pizer why he went into hiding after the deaths of Polly Nichols and Annie Chapman, Pizer said that his brother had advised him to do so.

“I was the subject of a false suspicion,” he said emphatically.

“It was not the best advice that could be given to you,” Baxter returned.

Pizer shot back immediately,

“I will tell you why. I should have been torn to pieces!”

Annie Chapman became a victim of the Ripper after being turned away from her lodgings

‘No mere slaughterer of animals’

On 26 September the coroner summed up the evidence, including the eyewitness testimony of a Mrs Long, who may have been the first person to give a description of Jack The Ripper.

‘At half-past five, Mrs. Long . . . remembers having seen a man and woman standing a few yards from the place where the deceased is afterwards found. And, although she did not know Annie Chapman, she is positive that that woman was the deceased. The two were talking loudly, but not sufficiently so to arouse her suspicions that there was anything wrong. Such words as she overheard were not calculated to do so. The laconic inquiry of the man, “Will you?” and the simple assent of the woman, viewed in the light of subsequent events, can be easily translated and explained. Mrs. Long passed on her way, and neither saw nor heard anything more of her, and this is the last time she is known to have been alive.

[Neighbour Albert] Cadosch says it was about 5.20 when he was in the backyard of the adjoining house, and heard a voice say “No,” and three or four minutes afterwards a fall against the fence.

The street door and the yard door were never locked, and the passage and yard appear to have been constantly used by people who had no legitimate business there. There is little doubt that the deceased knew the place, for it was only 300 or 400 yards from where she lodged. The wretch must have then seized the deceased, perhaps with Judas-like approaches. He seized her by the chin. He pressed her throat, and while thus preventing the slightest cry, he at the same time produced insensibility and suffocation. There is no evidence of any struggle. The clothes are not torn. Even in these preliminaries, the wretch seems to have known how to carry out efficiently his nefarious work.

The deceased was then lowered to the ground, and laid on her back; and although in doing so she may have fallen slightly against the fence, this movement was probably effected with care. Her throat was then cut in two places with savage determination, and the injuries to the abdomen commenced. All was done with cool impudence and reckless daring; but, perhaps, nothing is more noticeable than the emptying of her pockets, and the arrangement of their contents with business-like precision in order near her feet. The murder seems, like the Buck’s-row case, to have been carried out without any cry. Sixteen people were in the house. The partitions of the different rooms are of wood. None of the occupants of the houses by which the yard is surrounded heard anything suspicious.

The brute who committed the offence did not even take the trouble to cover up his ghastly work, but left the body exposed to the view of the first comer. This accords but little with the trouble taken with the rings, and suggests either that he had at length been disturbed, or that as the daylight broke a sudden fear suggested the danger of detection that he was running. There are two things missing. Her rings had been wrenched from her fingers and have not been found, and the uterus has been removed. The body has not been dissected, but the injuries have been made by some one who had considerable anatomical skill and knowledge. There are no meaningless cuts. It was done by one who knew where to find what he wanted, what difficulties he would have to contend against, and how he should use his knife, so as to abstract the organ without injury to it. No unskilled person could have known where to find it, or have recognised it when it was found. For instance, no mere slaughterer of animals could have carried out these operations. It must have been some one accustomed to the post-mortem room.

The conclusion that the desire was to possess the missing part seems overwhelming. We are driven to the deduction that the mutilation was the object, and the theft of the rings was only a thin-veiled blind, an attempt to prevent the real intention being discovered. It has been suggested that the criminal is a lunatic with morbid feelings. This may or may not be the case; but the object of the murderer appears palpably shown by the facts, and it is not necessary to assume lunacy, for it is clear that there is a market for the object of the murder.

Within a few hours of the issue of the morning papers containing a report of the medical evidence given at the last sitting of the Court, I received a communication from an officer of one of our great medical schools, that they had information which might or might not have a distinct bearing on our inquiry. I attended at the first opportunity, and was told by the sub-curator of the Pathological Museum that some months ago an American had called on him, and asked him to procure a number of specimens of the organ that was missing in the deceased. He stated his willingness to give £20 for each, and explained that his object was to issue an actual specimen with each copy of a publication on which he was then engaged. Although he was told that his wish was impossible to be complied with, he still urged his request. He desired them preserved, not in spirits of wine, the usual medium, but in glycerine, in order to preserve them in a flaccid condition, and he wished them sent to America direct. It is known that this request was repeated to another institution of a similar character.

It is, therefore, a great misfortune that nearly three weeks have elapsed without the chief actor in this awful tragedy having been discovered. Surely, it is not too much even yet to hope that the ingenuity of our detective force will succeed in unearthing this monster. It is not as if there were no clue to the character of the criminal or the cause of his crime. His object is clearly divulged. His anatomical skill carries him out of the category of a common criminal, for his knowledge could only have been obtained by assisting at post-mortems, or by frequenting the post-mortem room. If Mrs. Long’s memory does not fail, and the assumption be correct that the man who was talking to the deceased at half-past five was the culprit, he is even more clearly defined. In addition to his former description, we should know that he was a foreigner of dark complexion, over forty years of age, a little taller than the deceased, of shabby-genteel appearance, with a brown deer-stalker hat on his head, and a dark coat on his back.’

A verdict of wilful murder against a person or persons unknown was then entered.

It is thought that Mrs Long had formed the impression that Chapman’s companion was a foreigner from his accent, as she didn’t see his face. For many years this has been understood to mean that he was a European, most likely a Jew, but evidence recently uncovered points to the possibility that he might have been an American, which would tie in with the coroner’s story of the doctor who expressed an interest in purchasing anatomical specimens.

A surplus of suspects

Contrary to contemporary public opinion and the claims made by an impatient press, the police made exhaustive inquiries in the area following the murder of Annie Chapman, visiting over 200 common lodging houses and following every single lead offered by anxious residents, all of which led to a dead end. Then, as now, there were people in the habit of making false confessions, either because they were mentally disturbed or because they were seeking attention. And, of course, there were many false and malicious claims made against innocent people which the police were obliged to investigate.

During September Sir Charles Warren came under increasing pressure from the Home Office, which wanted assurances that the police would be making an imminent arrest. In an effort to placate them, he submitted a confidential report in which he detailed the individuals currently under suspicion.

‘No progress has yet been made in obtaining any definite clue to the Whitechapel murderers. A great number of clues have been examined and exhausted without finding anything suspicious. A large staff of men are employed and every point is being examined which seems to offer any prospect of a discovery.

There are at present three cases of suspicion.

1. The lunatic Isensmith [sic], a Swiss arrested at Holloway who is now in an asylum at Bow and arrangements are being made to ascertain whether he is the man who was seen on the morning of the murder in a public house by Mrs Fiddymont.

2. A man called Puckeridge was released from an asylum on 4 August. He was educated as a surgeon and has threatened to rip people up with a long knife. He is being looked for but cannot be found as yet.

3. A Brothel Keeper who will not give her address or name writes to say that a man living in her house was seen with blood on him on the morning of murder. She described his appearance and said where he might be seen. When the detectives came near he bolted, got away and there is no clue to the writer of the letter.

All these three cases are being followed up and no doubt will be exhausted in a few days – the first seems a very suspicious case, but the man is at present a violent lunatic.’

Of the three suspects, Isenschmid seemed the most likely perpetrator at the time. He had been arrested on 12 September after two doctors and the landlady of a public house had reported his eccentric and threatening behaviour to the police. Dr Cowan and Dr Crabb informed the authorities that in their professional opinion Isenschmid was a violent lunatic and that he disappeared from his lodgings at odd hours of the night. He was also known to have a habit of sharpening knives in the vicinity of anyone he didn’t like the look of, as if to intimidate them. Four days earlier, on the morning of the Chapman murder, Mrs Fiddymout, the landlady of the Prince Albert public house, had been disturbed by the appearance of a furtive man who had a wild look in his eyes and dried blood on his hands. It was Isenschmid, but his brother supplied an alibi for his movements on the day of the Chapman murder and he was released after the Ripper struck again while he was still under arrest.

Oswald Puckridge still looks like a viable suspect, although he was 50 years old at the time of the Ripper murders, which does not conform with the eye-witness descriptions. He was released from Hoxton House Lunatic Asylum three days before Martha Tabram was murdered and he ended his days in Holborn Workhouse on 28 May 1900, so he was at large during the crucial period. However, there is no evidence of any kind to connect him with the killings.

The third man referred to in Warren’s report was probably Francis Tumblety, an American doctor, who, in the light of recently uncovered evidence, now seems a very likely candidate for the Whitechapel murders.

An unfortunate double event – 30 September 1888

‘Long Liz’ was comparatively fortunate in that she was spared the ghastly mutilations which the Whitechapel fiend had inflicted on the other women and was instead despatched with a single slice of a razor-sharp blade. However, for this reason there is still some doubt that she was an ‘official’ Ripper victim, but may have been slain by another hand. In all other respects her story was much like the other women.

A farmer’s daughter and Swedish by birth, Elizabeth Stride had left her home country in 1866 and emigrated to England after the death of her parents and the trauma of having given birth to a stillborn baby. Her marriage to carpenter John Stride did not last long and she was soon walking the streets of Whitechapel. On the night of her death, in the early hours of 30 September 1888, she had been working as a cleaner in Flower And Dean Street but needed to supplement her pitiable income by prostitution.

By all accounts she was slim and pretty, a more attractive prospect than the dowdy bawds with whom she shared a pitch, and she had made an effort to make herself presentable for the punters. To her long, black, fur-trimmed jacket she had pinned a red rose, which proved an important detail when it came to establishing her movements and the veracity of the various conflicting witness statements. In addition she was wearing a black crêpe bonnet, a dark threadbare skirt, a brown bodice, white stockings and the customary side-spring boots.

It was the rose which helped PC William Smith to be confident that it was Stride he had seen with a man in Berner Street 30 minutes after midnight. Her companion was 170cm (5ft 7in) tall, of respectable appearance, and carried a small parcel wrapped in newspaper which the constable estimated was 15–20cm (6–8in) broad and about 45cm (18in) long – the right size to contain a small medical bag, perhaps? He was about 28 years of age, with a dark complexion and a small dark moustache, and was wearing a dark coat, dark trousers, white collar and tie and a hard felt deerstalker hat of the kind made famous by Sherlock Holmes.

A second witness

Fifteen minutes later Israel Schwartz, a Hungarian Jewish immigrant who spoke little English, witnessed a struggle at the very spot where Stride’s body was later found, by the gate to Dutfield’s Yard in Berner Street. The man was attempting to drag the woman into the street, then threw her to the ground whereupon she screamed. Frightened of becoming involved in a violent argument, Schwartz crossed over the road, passing a second man who was lighting his pipe. A moment later the first man called out ‘Lipski!’ (a derogatory generic name for a Jew, deriving from the name of a notorious murderer who was still in the public mind at that time), whereupon the pipe-smoker gave chase and Schwartz fled, fearing for his life.

After evading his pursuer Schwartz reported the incident to the police and gave the following descriptions of the two men, neither of whom conforms to the descriptions of previous suspects. The man who assaulted the woman was approximately 165cm (5ft 5in) tall, round-faced and broad-shouldered, with dark hair and a short brown moustache. He was wearing a dark jacket and trousers and a dark peaked cap. Schwartz thought he might have been about 30 years of age. The man with the pipe was in his mid-thirties, 180cm (5ft 11in) tall, with light brown hair, and was wearing a dark overcoat and a black wide-brimmed hat.

Was it the Ripper?

A possible explanation for the incident might be that the first man took exception to a stranger – particularly a Jew – being a witness to his argument with the woman and may have ordered his friend to give chase. This second sighting is the more intriguing as it places Stride at the murder scene just 15 minutes before her death and raises the distinct possibility that she was murdered by the men Schwartz saw and not the Ripper. This would explain why there were no post-mortem mutilations. And then there is the testimony of Dr Phillips, the police surgeon, who told the Stride inquest on 1 October that there was a ‘great dissimilarity’ between the Chapman and Stride murders, specifically the choice of weapon, which was a round-bladed knife in the latter case. This raises the possibility that Stride may have been murdered by her brutal former partner Michael Kidney, from whom she had separated only a few days earlier, and that Kidney was the man Schwartz had seen pushing her to the ground.

However, many Ripper historians disagree, arguing that Stride had still 15 minutes to meet her murderer after the two thugs had moved on and that the reason for the lack of mutilations was that the Ripper was interrupted by the arrival of a hawker, Louis Diemschutz, who pulled into Dutfield’s Yard in his pony and trap at 1am. When the horse shied Diemschutz looked to see what had disturbed it and saw what appeared to be a bundle of clothes on the ground. But it was too dark to see clearly. The only light in the yard came from the windows of a socialist club to the right and from the second-storey windows of the tenement opposite. The fitful light from the street lamp outside was not strong enough to illuminate the yard even though Diemschutz had left the gate wide open. So he prodded the bundle with his whip and then lit a match which blew out in the wind – but the brief glimpse he caught was enough for him to see that it was a woman’s body. Her throat had been slit, the windpipe severed, the blood clotting a cheap check scarf around her neck. She was lying on her left side with her legs drawn up, knees together. In her left hand she clutched a packet of cheap breath fresheners, the contents of which had rolled into the gutter. Her right hand lay across her stomach, speckled with blood.

The body of Elizabeth Stride was still warm when Dr Frederick Blackwell examined it at the site just after 1.15am, which suggested that she had been killed between 12.45am and 1am when Diemschutz entered the yard. If he had disturbed the Ripper in the act then the killer’s bloodlust must have been unsatisfied and it would explain why he took such pitiless revenge on his second victim of the night, Catherine Eddowes.

Elizabeth Stride who was ‘despatched with a single slice of a razor-sharp blade’

Inquest into the death of Elizabeth Stride

On the first day of the inquest into the death of Elizabeth Stride on 2 October 1888, Dr George Bagster Phillips testified:

‘On Oct. 1, at three p.m., at St. George’s Mortuary, Dr. Blackwell and I made a post-mortem examination, Dr. Blackwell kindly consenting to make the dissection, and I took the following note:

“Rigor mortis still firmly marked. Mud on face and left side of the head. Matted on the hair and left side. We removed the clothes. We found the body fairly nourished. Over both shoulders, especially the right, from the front aspect under collar bones and in front of chest there is a bluish discolouration which I have watched and seen on two occasions since. On neck, from left to right, there is a clean cut incision six inches in length; incision commencing two and a half inches in a straight line below the angle of the jaw. Three-quarters of an inch over undivided muscle, then becoming deeper, about an inch dividing sheath and the vessels, ascending a little, and then grazing the muscle outside the cartilages on the left side of the neck. The carotid artery on the left side and the other vessels contained in the sheath were all cut through, save the posterior portion of the carotid, to a line about 1-12th of an inch in extent, which prevented the separation of the upper and lower portion of the artery. The cut through the tissues on the right side of the cartilages is more superficial, and tails off to about two inches below the right angle of the jaw. It is evident that the haemorrhage which produced death was caused through the partial severance of the left carotid artery . . .

I have come to a conclusion as to the position of both the murderer and the victim, and I opine that the latter was seized by the shoulders and placed on the ground, and that the murderer was on her right side when he inflicted the cut. I am of opinion that the cut was made from the left to the right side of the deceased, and taking into account the position of the incision it is unlikely that […] a long knife inflicted the wound in the neck.

Coroner: From the position you assume the perpetrator to have been in, would he have been likely to get bloodstained?

Dr Phillips: Not necessarily, for the commencement of the wound and the injury to the vessels would be away from him, and the stream of blood – for stream it was – would be directed away from him, and towards the gutter in the yard.

Coroner: But why did she not cry out while she was being put on the ground?

Dr Phillips: She was in a yard, and in a locality where she might cry out very loudly and no notice be taken of her. It was possible for the woman to draw up her legs after the wound, but she could not have turned over. The wound was inflicted by drawing the knife across the throat. A short knife, such as a shoemaker’s well-ground knife, would do the same thing. My reason for believing that deceased was injured when on the ground was partly on account of the absence of blood anywhere on the left side of the body and between it and the wall.’

At the close of the inquest Dr Blackwell was called to give evidence and, asked by the foreman of the jury if he had noticed any marks or bruises about the shoulders, replied, ‘They were what we call pressure marks. At first they were very obscure, but subsequently they became very evident. They were not what are ordinarily called bruises; neither is there any abrasion. Each shoulder was about equally marked.’

In summing up on the final day the coroner attempted to clarify the apparently conflicting testimony of three key witnesses who claimed to have seen a woman answering the description of the deceased in the company of a man near the location where the body was discovered between 15 minutes and an hour later.

‘William Marshall, who lived at 64, Berner-street, was standing at his doorway from half-past 11 till midnight. About a quarter to 12 o’clock he saw the deceased talking to a man between Fairclough-street and Boyd-street. There was every demonstration of affection by the man during the ten minutes they stood together, and when last seen, strolling down the road towards Ellen Street, his arms were round her neck.

At 12 30 p.m. the constable on the beat (William Smith) saw the deceased in Berner Street standing on the pavement a few yards from Commercial-street, and he observed she was wearing a flower in her dress.

A quarter of an hour afterwards James Brown, of Fairclough-street, passed the deceased close to the Board school. A man was at her side leaning against the wall, and the deceased was heard to say, “Not to-night, but some other night.” Now, if this evidence was to be relied on, it would appear that the deceased was in the company of a man for upwards of an hour immediately before her death, and that within a quarter of an hour of her being found a corpse she was refusing her companion something in the immediate neighbourhood of where she met her death. But was this the deceased? And even if it were, was it one and the same man who was seen in her company on three different occasions?

With regard to the identity of the woman, Marshall had the opportunity of watching her for ten minutes while standing talking in the street at a short distance from him, and she afterwards passed close to him. The constable feels certain that the woman he observed was the deceased, and when he afterwards was called to the scene of the crime he at once recognized her and made a statement; while Brown was almost certain that the deceased was the woman to whom his attention was attracted. It might be thought that the frequency of the occurrence of men and women being seen together under similar circumstances might have led to mistaken identity; but the police stated, and several of the witnesses corroborated the statement, that although many couples are to be seen at night in the Commercial-road, it was exceptional to meet them in Berner Street.

With regard to the man seen, there were many points of similarity, but some of dissimilarity, in the descriptions of the three witnesses; but these discrepancies did not conclusively prove that there was more than one man in the company of the deceased, for every day’s experience showed how facts were differently observed and differently described by honest and intelligent witnesses. Brown, who saw least in consequence of the darkness of the spot at which the two were standing, agreed with Smith that his clothes were dark and that his height was about 5ft. 7in., but he appeared to him to be wearing an overcoat nearly down to his heels; while the description of Marshall accorded with that of Smith in every respect but two. They agreed that he was respectably dressed in a black cut away coat and dark trousers, and that he was of middle age and without whiskers.

On the other hand, they differed with regard to what he was wearing on his head. Smith stated he wore a hard felt deer stalker of dark colour; Marshall that he was wearing a round cap with a small peak, like a sailor’s. They also differed as to whether he had anything in his hand. Marshall stated that he observed nothing. Smith was very precise, and stated that he was carrying a parcel, done up in a newspaper, about 18in. in length and 6in. to 8in. in width. These differences suggested either that the woman was, during the evening, in the company of more than one man – a not very improbable supposition – or that the witness had been mistaken in detail. If they were correct in assuming that the man seen in the company of the deceased by the three was one and the same person it followed that he must have spent much time and trouble to induce her to place herself in his diabolical clutches.

In the absence of motive, the age and class of woman selected as victim, and the place and time of the crime, there was a similarity between this case and those mysteries which had recently occurred in that neighbourhood. There had been no skilful mutilation as in the cases of Nichols and Chapman, and no unskilful injuries as in the case in Mitre Square, possibly the work of an imitator; but there had been the same skill exhibited in the way in which the victim had been entrapped, and the injuries inflicted, so as to cause instant death and prevent blood from soiling the operator, and the same daring defiance of immediate detection, which, unfortunately for the peace of the inhabitants and trade of the neighbourhood, had hitherto been only too successful.’

After a short deliberation the jury returned a verdict of ‘Wilful murder against some person or persons unknown’ and the inquest into the death of Long Liz was concluded.

Murder in Mitre Square

Forty-six-year-old Catherine Eddowes had not entirely slept off her drink when her cell door was opened at 12.55am and she was ushered on her way by the jailer at Bishopsgate police station. She had been singing softly to herself for almost an hour and was deemed sufficiently sober to be released. ‘I am capable of taking care of myself now,’ she assured PC Hutt, the duty officer, as she made her way unsteadily towards the exit at the end of a passage. Then she enquired, ‘What time is it?’ PC Hutt replied it was just before one and too late for her to get any more drink, to which Eddowes responded, ‘I shall get a fine hiding when I get home, then.’

‘Serves you right,’ said the PC as he watched her cross the station yard, adding that he would be obliged if she could close the back door on her way out. ‘All right,’ she replied. ‘Good night, old cock.’

It was beginning to rain as she turned down Houndsditch toward Aldgate High Street, but her black straw bonnet would keep her hair from getting bedraggled. She wore a black cloth jacket trimmed with imitation fur, a brown bodice and a green alpaca skirt with a white apron, which gave her an appearance more in keeping with a charwoman than a streetwalker.

Eight minutes later she entered Mitre Square, a gloomy, ill-lit quadrangle bounded on all sides by grim, imposing warehouses. About 20 minutes later PC Watkins crossed the square, shining his bull’s-eye lamp into the dark recesses of the quadrangle and, seeing nothing unusual, he continued on his beat, which took 12–14 minutes to complete. Had he not stopped for a cup of tea offered by a night watchman he might have caught the Ripper in the act.

Another body found

At 1.35am three men, Joseph Lawende, Joseph Levy and Harry Harris, passed a couple taking shelter at the corner of Church Passage which led into the square. Lawende did not see the woman’s face as she had her back to him and could only describe her as being short. She was wearing a black bonnet and a jacket of the same colour. It is likely that it was Catherine Eddowes and that her companion was her murderer. She had her hand on his chest, indicative of intimacy, and they were conversing quietly. Lawende caught only a glimpse of the man who he later described as ‘rough and shabby’, aged about 30, approximately 165cm (5ft 7in) tall and of medium build with a fair complexion and a fair moustache. He was wearing a grey peaked cloth cap and a pepper and salt-coloured jacket with a reddish handkerchief tied around his neck. But it was such a fleeting glimpse that Lawende later admitted to the police that he would not be confident of recognizing the man if he ever came face to face with him. His friends could add nothing to the description, although Levy observed that the couple were rum-looking characters who made him uncomfortable and that he was glad not to be walking alone in that area at night. Ten minutes later PC Watkins had completed his circuit and returned to Mitre Square. In the south-western corner he came upon the body of Catherine Eddowes ‘ripped open, like a pig in the market’.

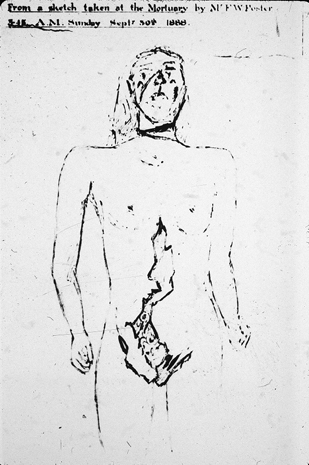

Her horrifying mutilations sickened even the seasoned City of London Police surgeon, Dr Brown, who was summoned to the scene at 2am.

‘The body was on its back,’ he noted. ‘The clothes [were] drawn up above the abdomen, the thighs were naked . . . the abdomen was exposed . . . great disfigurement of [the] face, the throat cut across . . .

‘The intestines were drawn out to a large extent and placed over the right shoulder – they were smeared over with some feculent matter, a piece [of] about two feet were quite detached from the body and placed between the body and the left arm, apparently by design. The lobe and auricle of the right ear was cut obliquely through . . . There were no traces of recent connection.’

When the body arrived at the mortuary a piece of her ear fell from the clothing in which it had been caught. During the post-mortem Dr Brown elaborated on the bizarre facial mutilations he had previously referred to.

‘There was a cut above a quarter of an inch through the lower left eyelid dividing the structures completely through. The upper eyelid on that side, there was a scratch through the skin on the left upper eyelid near to the angle of the nose. The right eyelid was cut through to half an inch. There was a deep cut over the bridge of the nose extending from the left border of the nasal bone down near to the angle of the jaw on the right side across the cheek, this cut went into the bone and divided all the structures of the cheek except the mucous membrane of the mouth. The tip of the nose was quite detached from the [rest of] the nose by an oblique cut from the bottom of the nasal bone to where the wings of the nose join on to the face . . . There was on each side of [the] cheek a cut which peeled up the skin forming a triangular flap about an inch and a half.’

Catherine Eddowes was murdered in Mitre Square, a gloomy quadrangle bounded by warehouses

The inquest

At the inquest on Thursday, 4 October, Dr Brown was asked to give details regarding the missing organs, and reported, ‘The uterus was cut away with the exception of a small portion, and the left kidney was also cut out. Both these organs were absent, and have not been found.’ The coroner then asked if he had any opinion as to what position the woman was in when the wounds were inflicted:

‘Dr Brown: In my opinion the woman must have been lying down. The way in which the kidney was cut out showed that it was done by somebody who knew what he was about.’

Coroner: Does the nature of the wounds lead you to any conclusion as to the instrument that was used?

Dr Brown: It must have been a sharp-pointed knife, and I should say at least 6 in. long.

Coroner: Would you consider that the person who inflicted the wounds possessed anatomical skill?

Dr Brown: He must have had a good deal of knowledge as to the position of the abdominal organs, and the way to remove them.

Coroner: Would the removal of the kidney, for example, require special knowledge?

Dr Brown: It would require a good deal of knowledge as to its position, because it is apt to be overlooked, being covered by a membrane.

Coroner: Would such a knowledge be likely to be possessed by some one accustomed to cutting up animals?

Dr Brown: Yes.

Coroner: Have you been able to form any opinion as to whether the perpetrator of this act was disturbed?

Dr Brown: I think he had sufficient time, but it was in all probability done in a hurry.

Coroner: How long would it take to make the wounds?

Dr Brown: It might be done in five minutes. It might take him longer; but that is the least time it could be done in.

Coroner: Have you any doubt in your own mind whether there was a struggle?

Dr Brown: I feel sure there was no struggle. I see no reason to doubt that it was the work of one man.

Coroner: Would you expect to find much blood on the person inflicting these wounds?

Dr Brown: No, I should not. I should say that the abdominal wounds were inflicted by a person kneeling at the right side of the body.’

Dr Brown was then asked if it was possible for the deceased to have been murdered elsewhere, and her body brought to where it was found:

‘Dr Brown: I do not think there is any foundation for such a theory. The blood on the left side was clotted, and must have fallen at the time the throat was cut. I do not think that the deceased moved the least bit after that.

Coroner: The body could not have been carried to where it was found?

Dr Brown: Oh, no.’

However, Dr Brown’s opinion was later contested by Dr G W Sequeira, who had been the first medical man on the scene that night, arriving at 1.55am, no more than 15 minutes after the murder had taken place. ‘I think that the murderer had no design on any particular organ of the body,’ he declared emphatically. ‘He was not possessed of any great anatomical skill.’

A sketch of Catherine Eddowes showing pre- and post-mortem injuries: a piece of her ear fell off in the mortuary

The Goulston Street graffiti

‘The Juwes are the men that will not be blamed for nothing.’ No one knows for certain if the writing found chalked on a wall in Goulston Street on the night of the double murder was a cryptic clue, or if it was merely a coincidence that a portion of Catherine Eddowes’ blood-spattered apron was found nearby. The bloodied piece of apron had been spotted at 2.55am by PC Alfred Long who, knowing of the murder in nearby Mitre Square, immediately realized its significance. While searching the immediate vicinity for other possible evidence he noticed the writing and made a note of it. The apron was lying in the passage of what was known as a model dwelling house near to the staircase leading up to Nos. 106 to 119. Long was certain it had not been there when he had passed that way on his previous round at 2.20am.

Detective Daniel Halse of the City Police elaborated on the find at the Catherine Eddowes inquest:

‘On Saturday, Sept. 29 [sic]. . . I proceeded to Goulston Street, where I saw some chalk-writing on the black fascia of the wall. Instructions were given to have the writing photographed, but before it could be done the Metropolitan police stated that they thought the writing might cause a riot or outbreak against the Jews, and it was decided to have it rubbed out, as the people were already bringing out their stalls into the street.

Coroner: Did the writing have the appearance of having been recently done?

Detective Halse: Yes. It was written with white chalk on a black fascia.

Foreman of the Jury: Why was the writing really rubbed out?

Detective Halse: The Metropolitan police said it might create a riot, and it was their ground.

Coroner: I am obliged to ask this question. Did you protest against the writing being rubbed out?

Detective Halse: I did. I asked that it might, at all events, be allowed to remain until Major Smith [acting Commissioner] had seen it.

Coroner: Why do you say that it seemed to have been recently written?

Detective Halse: It looked fresh, and if it had been done long before it would have been rubbed out by the people passing. I did not notice whether there was any powdered chalk on the ground, though I did look about to see if a knife could be found. There were three lines of writing in a good schoolboy’s round hand. The size of the capital letters would be about 3/4 in, and the other letters were in proportion. The writing was on the black bricks, which formed a kind of dado, the bricks above being white.’

No clues in the chalk

Much has been made of the writing and the possible significance of the misspelling of the word Jews, which may or may not have been intentional. In Jack The Ripper: The Final Solution, author Stephen Knight spun a convoluted conspiracy theory concerning three mythical founders of the Freemasons known as the Juwes, which was subsequently revealed to have been inspired by an after-dinner story conceived in a moment of mischievous fun by the painter Walter Sickert and to have no basis in fact.

It seems fanciful in the extreme to presume that a serial killer would stalk the streets armed with a piece of chalk in the hope of finding a suitable surface on which to scrawl a provocative message – or that he would have paused to write anything that was not either a direct challenge to the police or in praise of his own audacity.

If he was inclined to bravado it is much more likely that he would have written something where the murder had been committed. And if he had written anything to taunt the police he would have dropped the bloodied chalk at the spot so that they would know that it was from the killer. Only an innocent would take the chalk away with them to use on another occasion.

Warren’s report to the Home Secretary, 6 November

Sir Charles Warren came under intense public criticism for having authorized the eradication of the Goulston Street graffiti and was forced to justify his action in a report to the Home Secretary.

Confidential

The Under Secretary of State

The Home Office

Sir,

In reply to your letter of the 5th instant, I enclose a report of the circumstances of the Mitre Square Murder so far as they have come under the notice of the Metropolitan Police, and I now give an account regarding the erasing of the writing on the wall in Goulston Street which I have already partially explained to Mr. Matthews verbally.

On the 30th September on hearing of the Berner Street murder, after visiting Commercial Street Station I arrived at Leman Street Station shortly before 5 A.M. and ascertained from the Superintendent Arnold all that was known there relative to the two murders.

The most pressing question at that moment was some writing on the wall in Goulston Street evidently written with the intention of inflaming the public mind against the Jews, and which Mr. Arnold with a view to prevent serious disorder proposed to obliterate, and had sent down an Inspector with a sponge for that purpose, telling him to await his arrival.

I considered it desirable that I should decide the matter myself, as it was one involving so great a responsibility whether any action was taken or not.

I accordingly went down to Goulston Street at once before going to the scene of the murder: it was just getting light, the public would be in the streets in a few minutes, in a neighbourhood very much crowded on Sunday mornings by Jewish vendors and Christian purchasers from all parts of London.

There were several Police around the spot when I arrived, both Metropolitan and City.

The writing was on the jamb of the open archway or doorway visible in the street and could not be covered up without danger of the covering being torn off at once.