The myth of Jack the Ripper came into existence on the morning of 27 September 1888. Prior to that date the deaths of Martha Tabram, Polly Nichols and the earlier, unrelated slaying of Emma Smith had all been attributed to an anonymous fiend known only as the Whitechapel Murderer. But as soon as T.J. Bulling, the editor of the Central News Agency (a clearing house for correspondents), opened a letter addressed to ‘The Boss’ written in red ink he knew that the British press had a name that would capture the public imagination and sell newspapers in unprecedented numbers.

‘Dear Boss,

I keep on hearing the police have caught me but they won’t fix me just yet. I have laughed when they look so clever and talk about being on the right track. That joke about Leather Apron gave me real fits. I am down on whores and I shan’t quit ripping them till I do get buckled. Grand work the last job was. I gave the lady no time to squeal. How can they catch me now? I love my work and want to start again. You will soon hear of me with my funny little games. I saved some proper red stuff in a ginger beer bottle over the last job to write with but it went thick like glue and I cant use it. Red ink is fit enough I hope. ha ha The next job I do I shall clip the lady’s ears off and send to the Police officers just for jolly, wouldn’t you? Keep this letter back till I do a bit more work, then give it out straight. My knife’s so nice and sharp,

I want to get to work right away if I get a chance.

Good luck.

Yours truly

Jack the Ripper

Don’t mind me giving the trade name’

The following was written vertically as a postscript:

‘Wasn’t good enough to post this before I got all the red ink off my hands curse it. No luck yet. They say I’m a doctor now ha ha’

Genuine message from the Ripper or a waste of police time? Most experts doubt the authenticity of this correspondence

The choice of name suggested that its creator was an educated man who hid his intelligence behind contrived grammatical errors. The inspiration for the appellation was obvious. The newspapers had been describing the murderer as ripping the bodies while Jack was a traditional name for the more colourful characters of English fiction. Jolly Jack Tar was a generic name for all sailors, the public hangman was traditionally referred to as Jack Ketch, a mischievous rogue would be called Jack the Lad and there were numerous villains synonymous with daring exploits who thumbed their noses at authority such as Spring-heeled Jack and Jack Shepherd the highwayman, who repeatedly escaped from Newgate prison. Clearly its creator was intent on giving the murderer a more romantic image. Only an irresponsible journalist would have no reservations about re-inventing a depraved serial killer as a daring rascal. The murderer is more likely to have viewed his bloody spree in vainglorious terms, perhaps as a holy crusade to rid the world of disease-riddled ‘undesirables’. He would have been insulted to think that the more popular press viewed him as a music-hall villain.

The public seemed to want every gory detail.

A second letter

On the Monday morning following the murders of Elizabeth Stride and Catherine Eddowes the Central News Agency received a second letter in the same handwriting postmarked October 1:

‘I wasn’t codding dear old Boss when I gave you the tip. youll hear about saucy Jack’s work tomorrow double event this time. Number one squealed a bit couldn’t finish straight off. Had no time to get ears for police thanks for keeping last letter back till I got to work again.

Jack the Ripper’

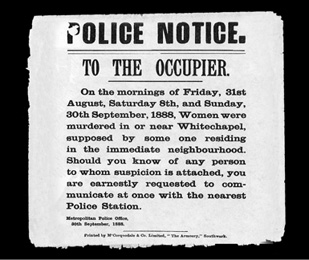

Knowing that they would not be able to prevent the letters from being published, Scotland Yard circulated copies to every police station with instructions that they should be put on display in the hope that someone might recognize the handwriting. The result was a flood of crank correspondence from all over the world by unstable individuals and malicious hoaxers who thought it would be fun to taunt the police.

One of the factors that casts doubt upon the authenticity of the first two letters is the fact that the writer did not send the victim’s ears to the police as he promised even though he had sufficient time to do so. Furthermore, the second letter did not predict the double murder committed on Sunday 30 September as is commonly thought. The letter was apparently posted on either Sunday night or Monday morning when the whole district would have been electrified with news of the killings at Berner Street and Mitre Square.

Modern London police officers John Douglas and Mark Olshaker dismiss the letters out of hand, as did their predecessor Sir Charles Warren. ‘It’s too organized, too indicative of intelligence and rational thought, and far too “cutesy”,’ declare Douglas and Olshaker. ‘An offender of this type would never think of his actions as “funny little games” or say that his “knife’s so nice and sharp”.’

The third taunt

A third communication was received by the Central News Agency on 5 October.

‘Dear Friend,

In the name of God hear me I swear I did not kill the female whose body was found at Whitehall. If she was an honest woman I will hunt down and destroy her murderer. If she was a whore God will bless the hand that slew her, for the women of Moab and Midian shall die and their blood shall mingle with the dust. I never harm any others or the Divine power that protects and helps me in my grand work would quit for ever.

Do as I do and the light of glory shall shine upon you. I must get to work tomorrow treble event this time yes yes three must be ripped. will send you a bit of face by post I promise this dear old Boss. The police now reckon my work a practical joke well well Jacky’s a very practical joker ha ha ha Keep this back till three are wiped out and you can show the cold meat

Yours truly, Jack the Ripper

Despite the boast there was no triple murder, which suggests that the author was not the killer – but if he was not, then why make the boast?

It is very likely that the agency’s own journalists were responsible for writing the three ‘Dear Boss’ letters, probably Bulling and his boss Charles Moore, who were suspected by Scotland Yard of having perpetrated the hoax in order to keep the story simmering and the newspaper proprietors eager to retain their agency’s services. If so, they can be credited with creating one of the most enduring trade names in history, but also with having wasted considerable police resources which were diverted from the investigation in the mistaken belief that this was a genuine communication from the murderer. Both men were shrewd enough to realize that a killer attracts little public interest until the press attach a sinister soubriquet to capture the imagination – a strategy which is as true today as it was 100 years ago.

Sir Robert Anderson was in no doubt that the letters were a hoax and even accuses an employee of the agency in his memoirs:

‘The Jack the Ripper letter which is preserved in the Police Museum at New Scotland Yard is the creation of an enterprising London journalist.’

Sir Melville Macnaghten came to the same conclusion:

‘In this ghastly production I have always thought I could discern the stained forefinger of the journalist, indeed, a year later, I had shrewd suspicions as to the actual author! But whoever did pen the gruesome stuff, it is certain to my mind that it was not the mad miscreant who had committed the murders. The name “Jack the Ripper”, however, had got abroad in the land and had “caught on”; it riveted the attention of the classes as well as the masses.’

Macnaghten’s suspicion appears to be borne out by crime writer R. Thurston Hopkins, who in 1935 wrote:

‘It was perhaps a fortunate thing that the handwriting of this famous letter was perhaps not identified, for it would have led to the arrest of a harmless Fleet Street journalist. This poor fellow had a breakdown and became a whimsical figure in Fleet Street, only befriended by staff of newspapers and printing works. He would creep about the dark courts waving his hands furiously in the air, would utter stentorian “Ha ha ha’s,” and then, meeting some pal, would buttonhole him and pour into his ear all the “inner story” of the East End murders. Many old Fleet Streeters had very shrewd suspicions that this irresponsible fellow wrote the famous Jack the Ripper letter, and even Sir Melville L. Macnaghten, Chief of the Criminal Investigation Department, had his eye on him.’

Of all the police officials involved in the case only Chief Inspector John George Littlechild was brave enough to name the journalist the Yard thought responsible for the ‘Dear Boss’ letters, but this may have been because Macnaghten and the others were reluctant to risk being sued for libel by accusing the journalists in print, whereas Littlechild named them in a private letter to journalist George Sims.

‘With regard to the term “Jack the Ripper” it was generally believed at the Yard that Tom Bullen [Bulling] of the Central News was the originator, but it is probable Moore, who was his chief, was the inventor. It was a smart piece of journalistic work. No journalist of my time got such privileges from Scotland Yard as Bullen. Mr James Munro when Assistant Commissioner, and afterwards Commissioner, relied on his integrity.’

From Hell

So the mystery of the ‘Dear Boss’ letters appears to have been resolved. However, there was a fourth piece of correspondence which could possibly have been sent by the killer. In contrast to the ornate copperplate script used in the first two letters the fourth is an almost illegible scrawl which is far more suggestive of a deranged mind. Unlike the first three, it was not signed Jack the Ripper. It was sent on 16 October to George Lusk, the head of the Mile End Vigilance Committee, in a small box with what the sender claimed was a section of Catherine Eddowes’ kidney. Dr Thomas Openshaw of the London Hospital established that it was a human adult kidney and Dr Brown the police surgeon stated that it exhibited signs of Bright’s Disease from which Eddowes was known to have suffered. It was also reported that the kidney had 5cm (2in) of renal artery attached which matched the 2.5cm (1in) that remained in the corpse. Significantly, the organ had been preserved in spirits rather than in the formalin that hospitals used for specimens, making it unlikely that it was a hoax perpetrated by medical students.

The text of the accompanying letter made disturbing reading:

From hell

M Lusk Sor

I send you half the Kidne I took from one women prasarved it for you, tother piece I fried and ate it was ver nise I may send you the bloody knif that took it out if you only wate a whil longer,

Signed

Catch me whenYou can

Mishter Lusk

However, a recently rediscovered contemporary interview with City Police surgeon Dr Brown contradicts the accepted view that the kidney belonged to Eddowes.

‘There is no portion of the renal artery adhering to it, it having been trimmed up, so consequently, there could be no correspondence established between the portion of the body from which it was cut. As it exhibits no trace of decomposition, when we consider the length of time that has elapsed since the commission of the murder, we come to the conclusion that the probability is slight of its being a portion of the murdered woman of Mitre Square.’

Fingerprint evidence

At the time of the Whitechapel murders forensic science was still in its infancy. The radical new theory suggesting that criminals could be identified by their unique individual fingerprints was beginning to be acknowledged grudgingly but had still to be proven in a British court of law. As early as 1879 Scottish physician Henry Foulds had used fingerprint evidence to catch a criminal and had drawn the authorities’ attention to its potential in an article published in a national magazine. The article sparked a heated public debate as to who was the true discoverer of fingerprinting, Foulds or his rival William Herschel, so the British police had no excuse for claiming that they were unaware of its value. But no one in authority appears to have even considered testing the technique on the ‘Dear Boss’ letters, for example, or the personal items found at the feet of Annie Chapman.

Although the first forensic laboratory was not established until 1910 it would not have been unrealistic for the London police of the 1880s to have retained hairs from the victim’s clothes for comparison with samples taken from each suspect and to have preserved these for future reference whenever a new suspect was brought in for questioning. A single bloody hair had been sufficient to convict a French duke of murdering his wife in 1847, but it took the British authorities another 50 years to appreciate the value of trace evidence.

Even photography, with which Mathew Brady had recorded the carnage on the battlefields of the American Civil War 25 years before the Ripper killings, was a novelty in British crime detection. No photographs were taken of any of the murder sites with the exception of the last, Miller’s Court, and the only body to be photographed in situ was again the last, that of Mary Kelly. The other victims were all photographed after they had been laid out in the mortuary, at which point the prints were of little use other than for identification. Had the Goulston Street graffiti been photographed before Sir Charles Warren had ordered it to be erased, the police might have possessed a vital clue as to its author and therefore its significance.

Again with the exception of Miller’s Court, the authorities failed to preserve the crime scenes. After an initial cursory glance around the immediate vicinity of the murders for cart tracks and a murder weapon they allowed crowds of curious onlookers to within a few feet of the bodies, thereby compromising the location and risking the obliteration of vital evidence such as footprints. Any physical clues left at the scene were washed away in the haste to scrub the stains from the streets.

Wasted opportunities

While a handful of resourceful investigators, such as the French criminologist Professor R.A. Reiss, were applying simple scientific methods and deductive reasoning in the manner of Sir Arthur Conan Doyle’s infallible fictional detective Sherlock Holmes, the British police still believed that the only sure way of securing a conviction was to catch the culprit in the act, or rely on witnesses and informers to identify the guilty party. Failing that, the alternative was to question everyone in the area at the time of the crime and follow up every lead – and while this method may have been practical for tracking down a known local character who had been seen fleeing the scene of the crime it proved impractical in tracking a shadow. No one had witnessed the Ripper in the act so they couldn’t lead the police to him or his associates.

Moreover, the Ripper was not the type of criminal the British police were used to dealing with. He was a lone killer who murdered strangers at random and so there was nothing to tie him to his victims. Had the motive been robbery there was a good chance that the stolen goods might have been traced and the culprit brought to justice. If it had been a crime of passion a relationship might have been established and friends of the deceased might have been pressed to provide a description. But the victims were strangers and the motive appears to have been gratuitous sadism, so instead of pursuing a trail the police scattered in all directions following a thousand false leads down as many blind alleys. With no serious leads to pursue they were forced to investigate suspicions, prejudices and malicious rumours.

The detectives were certainly familiar with the neighbourhood and its criminal fraternity, but they were fatally inflexible and blinkered in their approach to an investigation that demanded a radical new strategy.

Though criminal profiling was not fully developed as an aspect of forensic science until the 1970s, Dr Bond, the police surgeon, offered a detailed sketch of the Ripper in a report to Sir Charles Warren after the final murder in which he implies that the Whitechapel murderer was the Victorian detective’s nightmare – a lone unpredictable killer without friends or associates in the criminal underworld who could be induced to inform on him. Like so many serial killers he may have disarmed his victims by assuming an air of vulnerability, or he may have lured them with his superficial charm. By day he probably appeared unremarkable, even harmless, and so would not have drawn suspicion by his actions or his manner. The only people who would have seen the madness in his eyes were his victims in the seconds before he choked the life out of them.

The one thing that can be said of the Ripper killings is that they impressed upon the authorities the obvious need to establish basic crime-scene procedures, specifically the preservation of trace evidence as well as the routine photographing of the crime scenes. It was only with the Ripper killings that the British police were forced to face the fact that their leisurely methods may have been sufficient to catch petty thieves and drunken ruffians, but they were grossly inadequate for ensnaring an unpredictable, predatory serial killer.

Ten years before the East End atrocities Scotland Yard had established the first plain-clothes detective force, the CID (Criminal Investigation Department) but had failed to arm this elite squad with the modern tools and techniques of crime detection which were readily available. Instead, the British police chose to rely on tried and tested methods which belonged to an earlier age. Jack the Ripper woke them up to the harsh realities of the coming century.

The callous ritual sacrifice of Mary Kelly

It was generally believed at the time of the murders that the Ripper was a religious maniac. If true, it might explain why he mutilated Mary Kelly to the extent that he did and why he ceased his reign of terror immediately afterwards.

Mark Daniel, author of a novelization of the Jack the Ripper TV mini-series starring Michael Caine, recently proposed a scenario in which the killing served as a ritual sacrifice made in order to atone for the murderer’s previous transgressions and he has identified a specific extract from the Old Testament which may have provided the inspiration.

The presence of an uncommonly large fire in the grate at Miller’s Court had puzzled the police at the time as it was clearly too big to have been lit solely to provide illumination in such a tiny room. When scraps of clothing were found among the ashes it was presumed that the murderer had used it to consume some of his own bloodstained clothing, but a friend of Kelly’s later identified the charred remnants as belonging to clothes she had left earlier that day for Mary to mend. Burnt clothing produces smoke which would have filled the cramped room and made it impossible for the killer to breathe, but human fat would have fed the flames and prevented the fabric from creating smoke.

They sought him here, they sought him there, but they never quite knew who they were looking for.

Chapters 5–7 of Leviticus might provide a clue to the motive behind the murder:

‘And if a soul sin . . . then he shall bear his iniquity,

Or if a soul touch any unclean thing . . .

he shall also be unclean, and guilty . . .

Or if he touch the uncleanness of man . . .

then he shall be guilty.’

The language may be archaic but the meaning is clear. Sex with a whore, another man or an animal or the touching of unclean meat (as a horse butcher or slaughterman would be forced to do on a daily basis) would be considered a sin against God. Such a sin could only be expunged by a ritual sacrifice.

‘And he shall bring his trespass offering unto the Lord for his sin which he hath sinned, a female from the flock . . . for a sin offering . . .

And he shall bring them unto the priest, who shall offer that which is for the sin offering first, and wring off his head from his neck, but shall not divide it asunder

. . . And he shall offer the second for a burnt offering

. . . and it shall be forgiven him.’

Further verses give instructions for preparing the offering and evoke images of the hideous mutilations uncovered at Miller’s Court and the other murder sites.

‘It is the burnt offering, because of the burning upon the altar all night unto the morning . . .

And he shall offer of it all the fat thereof, the rump and the fat that covereth the inwards.

And the two kidneys, and the fat which is on them, which is by the flanks, and the caul that is above the liver, with the kidneys, it shall he take away:

. . . And the priest that offereth any man’s burnt offering, even the priest shall have to himself the skin of the burnt offering which he hath offered . . .

His own hand shall bring the offerings of the Lord made by fire, the fat with the breast, it shall he bring . . .

And the right shoulder shall ye give unto the priest for an heave offering . . . ’

This scenario might also explain the significance of the Goulston Street graffiti, assuming, of course, that the author was the murderer. ‘The Juwes are the men that will not be blamed for nothing’ could then be seen as an attempt to blame the Jews for having suggested that one’s sins could be forgiven by a ritual killing, a practice foreign to the Christian tradition.

By taking instructions from the Bible the Ripper would be able to justify his actions in his own twisted mind and return to some semblance of normal life free of guilt and maybe even with a sense of satisfaction and pride in his work.

The broken window is arrowed in this photograph of Mary Kelly’s lodging house taken the day after her murder

The diary of Jack the Ripper?

‘Before I have finished all England will know the name I have given myself.’

In 1991 workmen who were carrying out some rewiring in an old Victorian house in Liverpool pulled up the floorboards and found a black leatherbound volume which had lain there undisturbed for more than a century. Many pages had been torn out from the front section leaving just 63 leaves of handwritten entries in a fluid scrawl. But on closer examination it was seen to be no ordinary journal but the psychotic ramblings of a tormented soul who signed the final entry ‘Jack the Ripper’.

At least that is the version of events according to a local newspaper. The owner of the diary, scrap metal dealer Michael Barrett, claimed to have been given it by a dying friend, Tony Deveraux, who, we are to assume, obtained it from the workmen who discovered it. Before and after publication, serious doubts were raised as to the diary’s authenticity and Barrett was accused of perpetrating a hoax to rival that attempted by the forger of the notorious Hitler diaries, or at least attempting to pass off a forgery by an unidentified source as the genuine article. In his defence Barrett claimed that he pressed his friend to reveal how he came to possess the book, but Deveraux refused to say anything more. However, Deveraux’s daughter denied any knowledge of her father having owned such a book and added that he would have bequeathed it to her had it been his. The new owner of Battlecrease, the house in which it was allegedly found, also denied any knowledge of the discovery, as did the owner of the building firm which carried out the rewiring, who went so far as to question all of his workers. There was, however, a possible if tenuous link, and that is that the building workers were known to drink in the same pub in Liverpool, The Saddle Inn, which Deveraux and Barrett also frequented.

But what would be the significance of the missing pages? Critics of the diary suggested that they were torn out because they would have revealed the identity of the book’s real owner and they point out that certain stains and marks prove that it had been a photo album. In response, advocates of the diaries’ authenticity argued that the author would have torn out the preceding pages to obliterate any reminder of his wife and family. And they ask why a mentally disturbed individual would purchase a new journal when a defaced family journal would serve a more symbolic, ritualistic purpose.

The ‘Jack the Ripper’ diary

The author of the diary

As for the ‘author’ of the disputed diary, we are asked to believe that it was none other than James Maybrick, a wealthy Liverpudlian cotton merchant and the previous owner of Battlecrease, who was poisoned by his wife Florence in May 1889. His murder led to one of the most celebrated trials of the 19th century, but he had never even been considered as a suspect in the Whitechapel murders. The diary does not identify Maybrick by name, but it was allegedly found in a part of the house that had been his study and there are implicit references to his wife and children as well as his wife’s lover, against whom he becomes increasingly bitter: ‘I long for peace of mind, but I sincerely believe that it will not come until I have sought my revenge on the whore and the whore master.’

This shifting focus from his unfaithful wife to adulterous women in general sounds like the authentic voice of a psychotic, according to forensic psychologist Dr David Forshaw.

But a major problem remains. What connection did a Liverpool businessman have with London’s East End? The answer may lie in the following passage.

‘Foolish bitch. I know for certain that she has arranged a rendezvous with him in Whitechapel [referring to Whitechapel, Liverpool]. So be it. My mind is finally made. London it shall be and why not? Is it not an ideal location. Whitechapel, Liverpool, Whitechapel, London, ha ha no one could possibly place it together.’

The connection may not be as unlikely as it first appears. In his younger years Maybrick had lived in London’s East End and at the time of the murders it is believed that he kept a mistress there. The journey would have been a matter of just a few hours by train, but even so he wouldn’t have wanted to undertake it too often and this might account for the long gaps between the killings.

Today it is generally accepted that Polly Nichols was the first Ripper victim, but at the time the deaths of Emma Smith and Martha Tabram were attributed to the Whitechapel murderer, making Nichols the third. As the diary refers to the Bucks Row murder as the first it made it either a contemporary account by the only person who knew the truth or a modern fake.

The diary also mentions two small but significant details in the murder of Elizabeth Stride which only the most ardent Ripperologist would know, that she had red hair and that there is a possibility that her throat had been slashed with her own knife.

There is also a reference to two objects found at one of the murder scenes – an empty tin matchbox and a red leather cigarette case which the author of the diary claims to have left behind as a clue. Neither of these two objects were public knowledge until 1987 when the inventory detailing the victim’s belongings was published.

Another factor in the diary’s favour was the choice of subject. If it was a fake it would have been far easier to have made a lesser suspect fit the facts than Maybrick, whose life is known in greater detail.

Sketch of Elizabeth Stride’s murder scene.

A possible suspect?

As for Maybrick having motive, means and opportunity, it is a matter of historical record that his wife had a lover and that Maybrick had an addiction to strychnine and arsenic which, when taken in small doses, were a mild aphrodisiac and stimulant. A habitual user might have delusions of infallibility and be oblivious to danger or the possibility of being caught. Add to this the fact that Maybrick’s whereabouts cannot be accounted for on the night of the five ‘official’ Whitechapel murders and perhaps there is a compelling case for adding him to the list of suspects.

Maybrick was a well-known hypochondriac and visited his physician an astonishing 70 times during 1888, all of which are a matter of record. Not one of these appointments conflicts with the dates of the five canonical Ripper murders. Either the forger was uncannily lucky or the diary may just have been genuine.

Handwriting experts have declared the writing to be stylistically ‘of the period’ and the distinctive features to be characteristic of a deranged person. Moreover, these features (such as the crossing of two separated ‘t’s with a single flourish) reappear throughout the diary, which would be difficult for a forger to maintain. On the other hand, the script is wholly unlike that of James Maybrick when compared to his will. Again, advocates of the diary’s authenticity have a ready explanation. Maybrick was too ill to write his will and so dictated it to his brother. This scenario is reinforced by the fact that the name of Maybrick’s daughter has been misspelled in the will, a mistake a father would never make.

Forensics find the truth

The ‘acid test’ for any disputed document is, of course, the forensic dating of the paper and ink. In the case of the Ripper diary the British Museum confirmed that the paper did indeed date from the Victorian era (which was never in dispute) and that the fading of the ink was also consistent with its age.

However, powdered Victorian ink can be purchased in many antique stores and, though it may be in a poor state, it can be rendered usable by dilution with water. Ink can also be artificially dated, as the forgers of the Mussolini diaries have shown, by baking it in an oven for 30 minutes.

For many years following the publication of the diary, Ripper scholars were divided between those who accepted its authenticity with reservations and those who dismissed it as a forgery out of hand. It was only when ink samples were subjected to a specific test for the presence of chloroacetamide, a modern preservative, in October 1994 that the truth was finally revealed. The test proved positive. The diary was a fake and Barrett apparently confessed to being its author, though it is possible he only did this to remove the pressure of the publicity to which he was subjected. There are still Ripperologists who contend that the ink test is inconclusive perhaps because, like the general public, they prefer the myth to the facts.

Inside the disturbing mind of Jack the Ripper

It is a disturbing fact that Jack the Ripper was not unique. Two years before the Whitechapel murderer terrorized the East End, the German-born psychoanalyst Richard von Krafft-Ebing published a weighty academic study of sexual perversion detailing many true cases of sadistic sexual murder which bear an uncanny similarity to those perpetrated by the Ripper. Krafft-Ebing’s Psychopathia Sexualis was intended to prove that there was a scientific basis for all forms of sexual aberration so that the legal and medical authorities could understand the basis of these neuroses and psychoses and learn how to treat those who suffered from them. This influential study was revised and republished many times after its initial publication in 1886, with the Whitechapel case (number 17) added to a later edition. It remains a valued reference work for criminologists and profilers to this day.

‘(a) Lust-Murder (Lust Potentiated as Cruelty, Murderous Lust Extending to Anthropophagy).

The most horrible example, and one which most pointedly shows the connection between lust and a desire to kill, is the case of Andreas Bichel, which Feuerbach published in his “Aktenmassige Darstellung merkwurdiger Verbrechen”.

He killed and dissected the ravished girls. With reference to one of his victims, at his examination he expressed himself as follows: “I opened her breast and with a knife cut through the fleshy parts of the body. Then I arranged the body as a butcher does beef, and hacked it with an axe into pieces of a size to fit the hole which I had dug up in the mountain for burying it. I may say that while opening the body I was so greedy that I trembled, and could have cut out a piece and eaten it.”

Lombroso, too (“Geschlechtstrieb und Verbrechen in ihren gegenseitigen Beziehungen.” Goltdammer’s Archiv. Bd. xxx), mentions cases falling in the same category. A certain Philippe indulged in strangling prostitutes, after the sex act, and said: “I am fond of women, but it is sport for me to strangle them after having enjoyed them.”

A certain Grassi (Lombroso, op. cit., p. 12) was one night seized with sexual desire for a relative. Irritated by her remonstrance, he stabbed her several times in the abdomen with a knife, and also murdered her father and uncle who attempted to hold him back. Immediately thereafter he hastened to visit a prostitute in order to cool in her embrace his sexual passion. But this was not sufficient, for he then murdered his own father and slaughtered several oxen in the stable.

It cannot be doubted, after the foregoing, that a great number of so-called lust murders depend upon a combination of excessive and perverted desire. As a result of this perverse colouring of the feelings, further acts of bestiality with the corpse may result – e.g., cutting it up and wallowing in the intestines . . .

CASE 17. Jack the Ripper. On December 1, 1887, July 7, August 8, September 30, one day in the month of October and on the 9th of November, 1888; on the Ist of June, the 17th of July and the 10th of September, 1889, the bodies of women were found in various lonely quarters of London ripped open and mutilated in a peculiar fashion. The murderer has never been found. It is probable that he first cut the throats of his victims, then ripped open the abdomen and groped among the intestines. In some instances he cut off the genitals and carried them away; in others he only tore them to pieces and left them behind. He does not seem to have had sexual intercourse with his victims, but very likely the murderous act and subsequent mutilation of the corpse were equivalents for the sexual act.’

We may think that serial killers are a uniquely modern scourge, but the dozens of similar cases detailed in the Psychopathia Sexualis prove that the human capacity for evil has not diminished with our increased understanding of the human mind and ability to treat mental illness.

FBI file: profiling the Ripper

In 1988, exactly one hundred years after the Whitechapel murders, two FBI agents drew on their extensive experience of hunting serial killers to compile a psychological profile of Jack the Ripper. Special agents Roy Hazelwood and John Douglas approached the mystery as if it were a modern murder case, stripping away spurious speculation and the confusion created by numerous conspiracy theories to consider the case solely on the facts as recorded in the official police reports.

From the documented evidence, the location of the crime scenes and the nature of the attacks, the agents concluded that Jack was a white male in his mid- to late-twenties and possessed average intelligence. The fact that he went undetected was attributable to luck, not his cunning.

The Ripper was a habitual predatory killer who prowled the streets in anticipation of cornering a likely victim on whom he could indulge his perverted sexual fantasies. There was no pattern to the murders – they were spontaneous, opportunistic slayings. Such killers always stalk the same few streets, like a wild animal which has marked its territory. Had the police known at the time that the killer had a compulsion to repeatedly return to the scene of his crimes they might have been able to catch him in the act.

The Ripper’s background

His choice of victim, together with the nature of the mutilations, suggests the Ripper had been raised by a domineering female who is likely to have subjected him to repeated physical and sexual abuse. The effect of this would have been to create a child with sadistic, antisocial impulses, which may have driven him to torture animals and commit arson. Such tendencies would have continued into adult life when the Ripper would have exhibited extreme erratic behaviour, sufficient to provoke his neighbours and arouse the suspicions of the police. Therefore the authorities should have been looking for someone who had previously come to their attention for repeated acts of violence and irrational antisocial behaviour.

The Ripper was evidently single, had probably never married and was unlikely to have any friends. The fact that all the murders took place between midnight and 6am suggests that he was nocturnal by nature, lived alone and had no family responsibilities.

It is a fair assumption that he lived very close to the crime scenes, as predatory killers invariably start by murdering victims close to their homes, and it would appear that he knew the area well enough to carry out his crimes undetected and elude capture after being disturbed.

As for his appearance, he would have had poor personal hygiene and would have looked dishevelled, the very antithesis of the slumming gentleman of leisure cutting through the fog in top hat and cane envisaged in countless films and novels. If he was employed it would have been in a menial position and one in which he would have had little or no contact with the public. He was certainly not a professional man and, contrary to popular myth, the mutilations did not demonstrate medical knowledge, or even rudimentary surgical skill.

It is revealing that he subdued and killed his victims quickly as this indicates that the taking of a life was not of primary importance to him. The mutilations are the most significant clue to his state of mind. The murders were clearly sexually motivated and by displacing the victim’s sexual organs he was symbolically rendering them sexless and therefore no longer a threat. He clearly hated women and felt intimidated by them.

Using modern profiling techniques, Hazelwood and Douglas eliminated some of the prime suspects, notably Sir William Gull, and point the finger at one specific individual, Kosminski, whom they have confidently identified as Jack the Ripper.