On the evening of 10 February 1889 a short, neatly dressed man of European appearance walked into a Dundee police station and calmly informed the duty officer that his wife had committed suicide. When the police arrived at his home they found a woman’s body with severe injuries to the genitals and bruising around her throat. She had evidently been strangled and mutilated post-mortem. Moreover, the preliminary medical examination revealed that a second set of mutilations had been inflicted some time after the first by a sharp knife. The murderer had clearly returned to inflict more damage to satiate his sadistic appetite.

But that was not all. During their search of the premises the police found two curious messages chalked by a back door. They read ‘jack ripper is at the back of this door’ and ‘jack ripper is in this seller’ (sic). Was it possible that the Whitechapel murderer had fled to Scotland for fear that the police were closing in and had his wife been silenced to prevent her revealing that she knew of his crimes?

Further investigation uncovered a trunk containing a belt mottled with old, dried blood and two cheap imitation gold rings of the type that had been torn from Annie Chapman’s fingers.

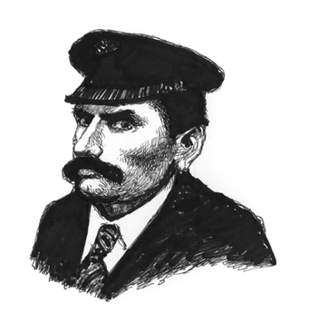

The trial of Jack the Ripper – William Henry Bury (1859–1889)

The name of the man they arrested and charged that night was William Henry Bury. During subsequent questioning detectives teased out more details which convinced them that the man they had in custody was more than just a wife murderer with delusions of notoriety.

He matched the description of the Whitechapel murderer given by several key witnesses. A photographic portrait taken in August 1888 shows Bury looking the very image of the man described by PC Smith and witness William Marshall in Berner Street on the day Elizabeth Stride was killed. He also fitted the psychological profile of the Ripper that would be drawn up by FBI profilers a century later.

A psychopathic personality

While still a boy Bury had witnessed his mother hauled off to a lunatic asylum and seen his father torn apart from groin to chin by the wheel of a cart – images which he may have been unconsciously exorcising during the Whitechapel murders. It has been said that Polly Nichols may have been killed simply because she was wearing a jacket with a picture of a man leading a horse, such associations being sufficient to trigger a violent response from a psychopathic personality.

According to contemporary accounts, Bury exhibited all the personality traits that define the psychopathic personality. He was a compulsive liar, a thief and suffered from acute paranoia. He carried knives with him for fear of being attacked and even slept with one under his pillow. He both feared and hated women and is thought to have caught venereal disease, possibly from his wife, Ellen Elliot, who continued to work as a prostitute despite having inherited £500 which Bury squandered on drink and other vices within a year of their marriage. That same year, 1887, they moved to Bow in London’s East End where Bury worked as a horsemeat butcher, a trade in which he could indulge his sadistic fantasies vicariously and perhaps even his need to avenge his father’s death, albeit on the carcass of dead animals.

More significantly, inquiries revealed that Bury could not account for his whereabouts on the nights of the East End murders and that he had exhibited signs of extreme agitation, behaving ‘like a madman’ after returning home on the night Annie Chapman had been killed. Whatever the reason for his unexplained nocturnal walks and bizarre behaviour, it is a fact that he sold his horse and cart in December 1888 shortly after the last Ripper murder and left London with Ellen in January 1889.

Final words

An indication of how seriously the police took the possibility of a ‘Ripper’ connection can be gleaned from the fact that Scotland Yard sent Inspector Abberline and another detective up to Scotland to assess the evidence and interview Bury in his cell. But Bury refused to confess. Even when the hangman stood before him he remained defiant. ‘I suppose you think you are clever to hang me,’ snarled Bury with venom. ‘But because you are to hang me you are not to get anything out of me.’ Evidently he was holding out for a reprieve in exchange for his full confession to the Whitechapel murders.

But was he the Ripper, or was this merely yet another of his warped, self-aggrandising fantasies? Abberline was apparently satisfied and is said to have told the executioner, ‘We are quite satisfied that you have hanged Jack the Ripper. There will be no more Whitechapel crimes.’ And that, at least, was true.

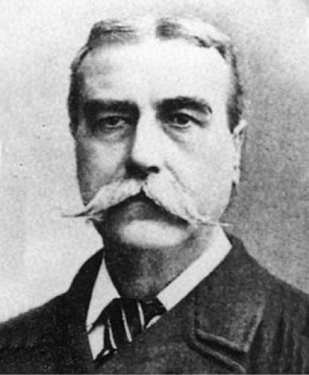

George Chapman (1865–1903)

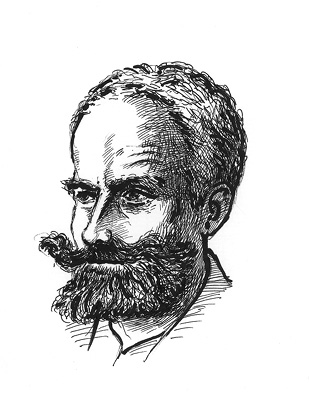

Polish-born Severin Antoniovich Klosowski assumed the name of George Chapman in 1895 in a belated attempt to evade the unwanted attentions of the British authorities, who were beginning to suspect him of having murdered several of his former wives. In one of the few surviving photographs, he looks the image of the dapper gent with his long black moustache, but in reality he was a callous, manipulative and violent man with a spiteful streak. But was he Jack the Ripper?

Before emigrating from Poland in the spring of 1887 Klosowski had worked as an assistant to a surgeon in Svolen and so would have possessed the medical skill to have performed the crude operations on each of the Whitechapel victims. However, he must have failed to qualify as a doctor because when he came to England he worked as a lowly barber’s assistant. Eventually he owned a barber shop of his own at 126 Cable Street which was within walking distance of all the Whitechapel murder sites.

But by 1890 his business had closed and he was forced to work again as a barber’s assistant, this time in a barber shop on the corner of Whitechapel Road and George Yard, only yards from where Martha Tabram had been murdered. In April the following year he and his second wife, Lucy Baderski, emigrated to America, where he continued his philandering ways and when she confronted him with his infidelities he would beat her in a fit of temper. At one point he attacked her with a knife which persuaded Lucy to return to England alone. He followed her and they were temporarily reconciled but eventually separated. Over the following months he took a series of common-law wives, subjected them to physical abuse and murdered each of them in turn as soon as he had tired of them.

George Chapman

A proven murderer

At his trial in 1903 Chapman was proven to be a serial murderer and clearly capable of sporadic outbursts of violence. However, the main problem with Chapman’s candidacy as a Ripper suspect is that he murdered all of his wives by poisoning them and murderers rarely change their modus operandi, although it is possible if they believe that they risk capture by continuing their pattern of behaviour. This apparently did not bother Inspector Abberline, who is said to have congratulated his colleague Inspector Godley on Chapman’s arrest with the words, ‘At last you have captured Jack the Ripper!’ Apparently not dissuaded by the fact that Chapman was only 23 years old during the Autumn of Terror, much younger than any of the men that the witnesses had described, Abberline later explained his optimism in an article published in the Pall Mall Gazette while Chapman was awaiting execution.

‘I have been so struck with the remarkable coincidences in the two series of murders that I have not been able to think of anything else for several days past – not, in fact, since the Attorney-General made his opening statement at the recent trial, and traced the antecedents of Chapman before he came to this country in 1888. Since then the idea has taken full possession of me, and everything fits in and dovetails so well that I cannot help feeling that this is the man we struggled so hard to capture fifteen years ago . . .

As I say, there are a score of things which make one believe that Chapman is the man; and you must understand that we have never believed all those stories about Jack the Ripper being dead, or that he was a lunatic, or anything of that kind. For instance, the date of the arrival in England coincides with the beginning of the series of murders in Whitechapel; there is a coincidence also in the fact that the murders ceased in London when Chapman went to America, while similar murders began to be perpetrated in America after he landed there. The fact that he studied medicine and surgery in Russia before he came over here is well established, and it is curious to note that the first series of murders was the work of an expert surgeon, while the recent poisoning cases were proved to be done by a man with more than an elementary knowledge of medicine. The story told by Chapman’s wife of the attempt to murder her with a long knife while in America is not to be ignored.

One discrepancy only have I noted, and this is that the people who alleged that they saw Jack the Ripper at one time or another, state that he was a man about thirty-five or forty years of age. They, however, state that they only saw his back, and it is easy to misjudge age from a back view.

As to the question of the dissimilarity of character in the crimes which one hears so much about, I cannot see why one man should not have done both, provided he had the professional knowledge, and this is admitted in Chapman’s case. A man who could watch his wives being slowly tortured to death by poison, as he did, was capable of anything; and the fact that he should have attempted, in such a cold-blooded manner, to murder his first wife with a knife in New Jersey, makes one more inclined to believe in the theory that he was mixed up in the two series of crimes . . . Indeed, if the theory be accepted that a man who takes life on a wholesale scale never ceases his accursed habit until he is either arrested or dies, there is much to be said for Chapman’s consistency. You see, [the] incentive changes; but the fiendishness is not eradicated. The victims too, you will notice, continue to be women; but they are of different classes, and obviously call for different methods of despatch.’

Chapman was hanged on 7 April 1903. Other factors in favour of him being the Ripper are that the murders began shortly after he arrived in England and stopped when he left; he had a regular job and was only free at the weekends when the murders took place; and he was known to have been walking the streets of the East End until the early hours. His insatiable sexual drive has been highlighted as a possible motive, but it could prove the opposite as the victims were not sexually assaulted. In fact, their mutilations indicate someone who was sexually inhibited and who could only exorcise his frustration through violence. Witnesses have described seeing a ‘foreigner’ in the company of some of the victims and this would match Chapman, but others claim to have overheard the supposed killer talking in English, which Chapman couldn’t have done at that time as his grasp of English was rudimentary to say the least.

Given all the facts, the case against Chapman is circumstantial at best and it is difficult to see why Abberline was so insistent that the Yard had finally got their man.

The doctor and the Devil

Doctor Roslyn D’Onston (real name Robert Donston Stephenson) was what criminologists would today call ‘a police buff’ – someone who gets a thrill by deliberately bringing themselves to the attention of the investigators, teasing them with misinformation and tantalizing clues. For such people the police are a tenacious but unimaginative adversary against whom they believe they can pit their superior intellect. But there was a more sinister side to Dr D’Onston, one which may explain his bravado as an unconscious desire to be caught and thus saved from fulfilling his pact with the Devil.

D’Onston was a self-confessed Satanist who practised black magic and boasted of his inside knowledge of the murders. He got a vicarious thrill from the thought that his mistress and close friends believed he was Jack the Ripper. He was also an alcoholic and a drug addict who revelled in the nickname ‘Sudden Death’, a morbid appellation which persuaded some investigators to consider him a strong suspect in the Whitechapel murders. And he had the opportunity to stalk and kill the victims, as he lived within walking distance of the murder scenes. But what motive might he have had to murder and mutilate five women?

Was it gross arrogance and perverted pride or idle speculation that led him to write an article for the Pall Mall Gazette three weeks after the final murder in which he offered a motive for the Ripper killings? By suggesting that the killer had butchered the victims to obtain a heart and body fat for use in black magic rituals was he hoping to divert attention away from his own diabolical practices, or was he unconsciously confessing to the crimes and taunting the police to make the connection? In the article D’Onston described the mutilations in graphic detail and with obvious relish, which suggests that he might have written the piece to satisfy his compulsion to confess and also to boast of what he had got away with. But later he accused a colleague whom the police were able to rule out of their inquiries.

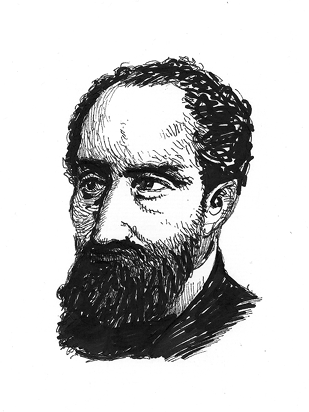

The only known photograph of Roslyn D’Onston, a Satanist who boasted of inside knowledge of the murders

A prime suspect?

It has been suggested that D’Onston may have accused another doctor knowing that he would be proven innocent so that the police would consider D’Onston a harmless eccentric with wild, unsubstantiated theories if his name came up as a suspect in subsequent enquiries, but those who knew Dr D. were not so easily fooled. His mistress, Mabel Collins, later claimed that D’Onston boasted of being Jack the Ripper and allegedly showed her physical evidence of his crimes. Collins subsequently confided her fears in a fellow Theosophist, Vittoria Cremers, who shared an apartment with D’Onston, after which Cremers made a thorough search of his rooms.

What she found there makes a convincing case for his claim to be the Whitechapel murderer: a small metal box containing several neckties encrusted with what appeared to be dried blood. These might have served as macabre tokens of his kills with which he could relive the thrill of the murder, or they may even have played a part in his satanic ceremonies.

D’Onston’s value as a prime suspect is strengthened by the fact that the notorious magician Aleister Crowley later took possession of the black box and claimed that it had belonged to Jack the Ripper.

As a bizarre postscript to this infernal affair, D’Onston recanted on his pact with the Devil shortly after the final murder and became a devout Christian, devoting the remainder of his days to writing a treatise on the Gospels.

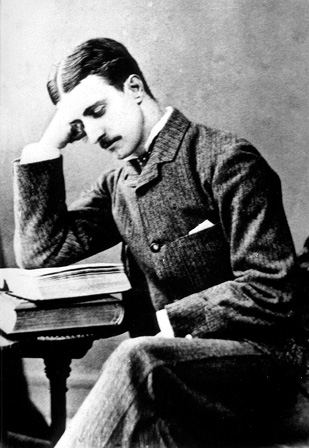

Montague John Druitt (1857–88)

Sir Melville Macnaghten has a lot to answer for. Had he not named Druitt, Kosminski and Ostrog in his infamous memorandum of 1891, they would never have been considered suspects in the Whitechapel murders. There is no hard evidence for assuming that any of them could have been responsible for the Ripper killings. Druitt was named because his death by drowning in the first week of December 1888 coincided with the end of the series of slayings and because his family suspected him of being the Ripper. It is true that his age at the time of the murders and his respectable appearance matched the descriptions given by several key witnesses, but he was a slight, slender man, not at all like the sturdy, broad-shouldered figure the witnesses described. There is also the matter of location. Druitt lived in Blackheath, not the East End, and it seems unlikely he could have slipped away from the murder scenes bespattered with blood and made his way back to Blackheath by public transport unobserved. Alternatively, he could have stayed overnight in a local lodging house, but his affluent appearance would have aroused suspicion.

Macnaghten, who did not join the Yard until June 1889, betrays his ignorance of the suspects by referring to Druitt as a doctor when in fact he was a barrister and schoolteacher. One can only assume that Macnaghten mistook the initials MD on Druitt’s belongings for a medical qualification or perhaps he assumed he had been a doctor as he came from a respected medical family. Either that or he was misled by errors in an earlier report. Whatever the reason, it is a careless mistake which is compounded by other errors – Druitt’s age, address and date of death – and assumptions, rendering the memorandum an item of historical interest but of little value to the investigation.

An unlikely candidate

So tenuous is the link between Druitt and the Whitechapel murders that one is tempted to consider the possibility that the real purpose of Macnaghten’s report was to submit a short list of candidates on whom the authorities could lay the blame should they be pressured to explain why they had failed to catch the killer.

Macnaghten’s suspicions are particularly unjustified in the case of Druitt, who was the son of a doctor, a graduate of Winchester College and an accomplished cricketer. In fact, he played in an important match in Dorset on 1 September, the day after the murder of Polly Nichols, and on 8 September he played at Blackheath only hours after the Annie Chapman murder – something perhaps only a real Dr Jekyll might have been able to pull off convincingly.

There are no reasonable grounds for Macnaghten’s assertion that Druitt was ‘sexually insane’. His abrupt dismissal from his teaching post at the Blackheath Boarding School for boys just a few weeks before his death may have been due to sexual misconduct or his increasingly erratic behaviour which Druitt feared might prove to be the first symptoms of insanity, a condition he was terrified he might have inherited from a member of his family. Druitt’s suicide note read: ‘Since Friday I felt I was going to be like mother, and the best thing for me was to die.’

There is no hint of dementia in the suicide note, only resignation and despair – not what one would expect from a tormented soul with the blood of five or more women on his hands. Moreover, the typical serial killer is driven by the need to prove his superiority over both his victims and the police. Few are known to have committed suicide, which would be seen as an admission of defeat.

Unfortunately Macnaghten’s musings were leaked to influential columnists such as George Robert Sims, who assumed it to be the Yard’s official line and so published speculation as fact, thereby adding to the many myths and misconceptions which have obscured the truth more effectively than the proverbial pea-souper London fog. In January 1889 Sims opined:

‘I have no doubt a great many lunatics have said they were Jack the Ripper on their death beds. It is a good exit . . . I don’t want to interfere . . . but I don’t quite see how the real Jack could have confessed seeing that he committed suicide after the horrible mutilation of the woman in the house in Dorset Street, Spitalfields. The full details of that crime have never been published – they never could be. Jack, when he committed that crime, was in the last stage of the peculiar mania from which he suffered. He had become grotesque in his ideas as well as bloodthirsty. Almost immediately after this murder he drowned himself in the Thames. His name is perfectly well known to the police. If he hadn’t committed suicide he would have been arrested.’

Secret misinformation

However, Macnaghten may not have been the only police official to have had suspicions regarding Druitt. In March 1889, Albert Backert, a founder of the Whitechapel Vigilance Committee, demanded to know why the police had recently reduced their presence in the East End and was informed that he would be told the truth if he promised to take an oath of secrecy. He later wrote:

‘Foolishly, I agreed. It was then suggested to me that the Vigilance Committee and its patrols might be disbanded as the police were quite certain that the Ripper was dead. I protested that, as I had been sworn to secrecy, I really ought to be given more information than this. “It isn’t necessary for you to know any more,” I was told. “The man in question is dead. He was fished out of the Thames two months ago and it would only cause pain to relatives if we said any more than that.”’

It is not known to whom Backert (an unreliable source) had spoken, but it was certainly not Inspector Abberline, who poured scorn on the whole idea of Druitt having been a serious suspect. In 1903 he told a reporter, ‘I know all about that story. But what does it amount to? Simply this. Soon after the last murder in Whitechapel the body of a young doctor was found in the Thames, but there is absolutely nothing beyond the fact that he was found at that time to incriminate him.’

Jill the Ripper

Hammer horror fans may be familiar with Dr Jekyll And Sister Hyde, the studio’s cheeky re-imagining of R.L. Stevenson’s morality tale in which the good doctor’s feminine side takes the upper hand and slaughters young Whitechapel women to obtain the hormones needed for her experiments. Implausible though it might sound, Inspector Abberline seriously considered a similar, if less fanciful, line of inquiry at the time of the Ripper murders.

Partly out of sheer frustration but also no doubt driven by the desire to pursue all avenues, no matter how unlikely, Abberline discussed the idea that Jack might be a Jill with colleague Dr Thomas Dutton. Dutton agreed that it was conceivable that a midwife could have possessed sufficient surgical skill to have removed the reproductive organs, but he thought it more likely that a man might have dressed in women’s clothes in order to pass through the streets at night without attracting suspicion – which, incidentally, was a theory favoured by Sir Arthur Conan Doyle. Had Conan Doyle pitched his fictional detective against the Ripper we can assume this is the solution he would have chosen.

A murderous midwife?

Either scenario might explain the discrepancies in the witness statements in the case of the Mary Kelly murder. The police surgeons estimated her time of death as around 4am, but local resident Mrs Caroline Maxwell was adamant that she had seen Kelly between 8 and 8.30 that morning and again an hour later, having recognized her by her clothes, specifically a maroon-coloured shawl that she had seen Kelly wearing on a previous occasion. If Mrs Maxwell had not mistaken the sighting for the day before, and assuming that the police surgeons were correct in estimating time of death, the only other explanation is that the murderer was wearing her clothes. If it was a man he would not have fooled the stranger Mrs Maxwell saw Kelly talking to outside the Prince Albert public house on the second occasion, but another woman in Kelly’s clothes might have engaged in conversation to avoid arousing suspicion. That said, it seems more likely that Mrs Maxwell was simply mistaken as to the day, though when Abberline questioned her again she stuck to her story.

A psychopathic midwife might sound absurd, but female serial killers are not unknown and in the East End of the 1880s a female Ripper would have enjoyed certain obvious advantages. She would have been able to move freely through the streets and, if questioned, would be able to explain her presence in the neighbourhood in the early hours of the morning. If she was unfortunate enough to get bloodstains on her clothing that too could be explained away.

Method and motive

In 1939 William Stewart was the first to speculate that the killer might be a woman in his book Jack the Ripper: A New Theory. His theory hinged on the answer to four crucial questions:

1. Who could walk the street at night without arousing suspicion or having to explain their movements to friends or family?

2. Who would have a viable reason for wearing bloodstained clothing?

3. Who would have had the skill to perform the crude operations in near darkness at speed and under stress?

4. Who might have been able to extricate themselves from suspicion if discovered leaning over the body?

But if it was a woman, what motive could she have had?

Stewart considered the possibility that she might have been an abortionist and if so, she may have been betrayed by a married woman whom she had tried to help which would have meant a prison sentence. The Whitechapel murders might therefore have been her revenge. In support of this theory it should be reiterated that no one heard the victims cry out, which could be explained by the fact that midwives who worked among the poor were apparently trained to induce un-consciousness in intoxicated or violent patients by exerting pressure on the nerve centres around the collar bone.

The main problem with the mad midwife scenario, however, is that there is no obvious connection between the victims and their murderer. Mary Kelly was the only victim who was pregnant at the time of her death. Stewart also ignores the testimony of Albert Cadosch, who claimed to have heard a man and woman conversing on the other side of the fence in the backyard of 29 Hanbury Street three minutes before something fell against the fence where the body of Annie Chapman was later found.

In support of his scenario Stewart raises the spectre of Mary Pearcey, who in October 1890 murdered her lover’s wife and child by cutting their throats and then wheeling their bodies in a barrow to a deserted street, where she dumped them. For those who doubt that a woman would have the strength to sever a throat with the force with which the Ripper despatched his victims Sir Melville Macnaghten said of Pearcey, ‘I have never seen a woman of stronger physique . . . her nerves were as iron cast as her body.’

A curious footnote to the case can be found in the fact that shortly before her execution Pearcey asked for a notice to be placed in a Spanish newspaper which read, ‘M.E.C.P. last wish of M.E.W. Have not betrayed.’

No doubt the conspiracy theorists will have much pleasure in speculating to whom those initials refer.

The lunatic fringe – Aaron Kosminski (1865–1919) and Michael Ostrog (1833–?)

Kosminski, by all accounts, was an even less likely suspect than Druitt. Macnaghten only named him because he was Swanson and Anderson’s chief suspect although there is no hard evidence to connect him. Again, Macnaghten passes judgment based on crucial errors and assumptions. Kosminski was indeed incarcerated in Colney Hatch asylum shortly after the cessation of the murders in 1891. However, he did not die soon afterwards as Macnaghten states – he was committed in 1894 – but 28 years later, during which time he did not commit any crimes or exhibit any signs of serious violence. In fact, he was a docile imbecile for most of his life and could not have been responsible for the brutal attacks which Macnaghten suspected him of. He had been a familiar figure in the East End, where he scavenged for scraps of food in the gutter and complained of hearing voices in his head. He was dirty and dishevelled, not the man of ‘shabby genteel’ appearance the witnesses had described. He cut a pathetic figure. No prostitute would have touched him and he would have been unaware of their presence.

The official file at Colney Hatch describes Kosminski as being ‘apathetic as a rule’ and ‘incoherent’. On only one occasion was he recorded as having threatened a member of staff with violence. If one thing can be stated with certainty, it is that Kosminski would not have been found guilty if he was on trial today.

Michael Ostrog

A habitual offender

The third suspect named by Macnaghten was a habitual thief and a compulsive liar, but there is no evidence to suggest that he ever killed anyone. Again, there is a nagging suspicion that he appears in the memorandum merely to give the impression that the police had their eye on a number of men whom they could have called in for questioning at any time, when in fact they had no definite leads at all.

Michael Ostrog, a Russian immigrant, had a police record stretching back to 1863, when he was arrested in Oxford for burglary under the alias Max Gosslar and sentenced to ten months’ hard labour. On his release, he travelled to Bishop’s Stortford, where he conned money from several of the more trusting inhabitants while posing as a Polish aristocrat until he was unmasked as a fraud and sentenced to a further three months’ imprisonment.

The next entry in his police file is dated July 1866, when he was sentenced to seven years’ penal servitude for theft. He was released in May 1873, only to reoffend six months later when he received a ten-year sentence. In September 1887 he was certified insane, following an incident in which he had tried to commit suicide by jumping in front of a train while handcuffed to a police escort.

A suspect vanishes

Less than six months later Ostrog was discharged and roaming the streets of Whitechapel during the ‘Autumn of Terror’, presumably no saner than he had been before his confinement in the asylum. On 26 October he was listed as being at large for failing to report at a police station as a condition of his release and was listed as ‘dangerous’. Yet he had exhibited no signs of violence other than the desire to die under the wheels of a train in the company of a gaoler.

It can only be assumed that he fitted the profile of the Ripper – a mentally unstable individual who had boasted of having rudimentary medical training. But his subsequent behaviour contradicts Macnaghten’s assessment that he was a ‘homicidal maniac’. He was arrested in 1891 and again in 1894 for petty theft, but on neither occasion did the police take the opportunity to charge him with the Whitechapel murders. On his release from prison in 1904 he vanished and was never heard of again.

Two strong candidates: James Kelly (1860–1929) and ‘GWB’

There is no evidence to connect wife-murderer James Kelly with Ripper victim Mary Kelly, but on the morning after Mary’s murder the police raided James Kelly’s lodgings only to discover that he had fled to Dieppe. Two days later, on 12 November, a police official whose initials were CET added a note to James Kelly’s file querying what steps had been taken to arrest him, although it is not clear whether this was in reference to his wife’s murder or the Whitechapel murders in general. The timing may have been purely coincidental. However, it is known that Inspector Monro took a keen interest in the whereabouts of James Kelly, who had been diagnosed a paranoid schizophrenic in Broadmoor Lunatic Asylum from which he had escaped in January 1888. Kelly had murdered his wife because he believed she had infected him with venereal disease, but during his stay in Broadmoor he became convinced that he had caught it from the whores of Whitechapel. Unfortunately, after his escape from the asylum his movements are unknown. He may have been lodging in Whitechapel and exercising revenge on the prostitutes who he blamed for infecting him, or he may have gone to ground elsewhere in an effort to evade the police who had a warrant for his arrest. There is no way of knowing for certain, but he remains a strong candidate.

‘GWB’ – an old man’s confession

The late Daniel Farson was one of the most respected Ripper scholars, whose most celebrated coup was the rediscovery of the Macnaghten Memoranda. His reputation made him an obvious clearing house for every crackpot theory regarding the Ripper, but one item of correspondence that he received in 1959 had an air of authenticity which he found difficult to dismiss.

The letter was sent from Australia by a man who signed himself ‘GWB’. In it, he told of his childhood in London’s East End during the late-1880s when his mother would chide him to come inside by calling, ‘Come in, Georgie, or Jack the Ripper will get you.’ On one occasion his father, a drunken brute, patted his son on the head and assured the boy that he would be the last person the Ripper would touch.

His father grew increasingly violent, beating Georgie’s mother so frequently that father and son stopped speaking to each other for many years. One evening in 1902, Georgie attempted a reconciliation with his father before sailing for Australia. It was then that the old man admitted that he had taken to drink in despair after having fathered a mentally retarded daughter, Georgie’s only sister. Having got that off his chest, the old man evidently felt that the moment was right to unburden himself of another secret and confessed to his son that he was guilty of the Whitechapel murders.

He explained that whenever he was violently drunk and the mood would take him he would seek out prostitutes and gut them with a sharp knife, avoiding the risk of getting blood on his clothes by wearing a second pair of trousers over his regular clothes which he would dispose of in the manure he was paid to deliver during the day.

A confession withheld

The old man urged Georgie to change his name when he reached Australia as he had made up his mind to go to the police and make a full statement before his death, but although the boy did as his father told him to the old man appears not to have been able to summon up the courage to confess.

Farson was of the opinion that the story was so simple and credible that it may just have been true. The father appeared to fit the description submitted by Lawende, who saw the murderer at Mitre Square, when the father would have been 38. But how seriously can one take the confession of a drunkard who had failed to make anything of himself and might have been merely bragging to impress his son, or perhaps to spite him by leaving the boy with the belief that he wouldn’t amount to anything as he had come from tainted stock?

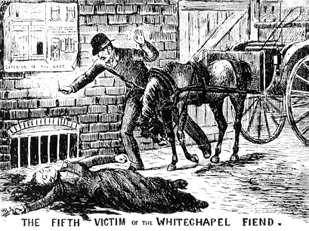

The discovery of Elizabeth Stride.

Portrait of a killer – Walter Sickert (1860–1942)

Interest in the Whitechapel murders has recently been rekindled as a result of the publicity surrounding crime novelist Patricia Cornwell’s personally financed investigation into the killings for her book Portrait Of A Killer. Cornwell is said to have spent $4 million of her own money to obtain original historical documents and to fund private scientific analysis of DNA specimens which she claims prove that the Victorian painter Walter Sickert was the Ripper. Ripperologists contend that her theory is fanciful in the extreme, that the science is inconclusive and that her deductions are fundamentally flawed.

The idea that Sickert might have been the Ripper was first advanced by author Donald McCormick in his study The Identity of Jack the Ripper (1959), expanded upon by Stephen Knight in Jack the Ripper: The Final Solution (1976) and made the subject of Jean Overton Fuller’s Sickert and the Ripper Crimes (1990) as well as Melvyn Fairclough’s Ripper and the Royals (2002). All five authors based their argument on the belief that Sickert had an unhealthy obsession with the seamier aspect of London life and the Whitechapel murders in particular and also that he used prostitutes as models. But the fact of the matter is that nearly all artists of the period paid prostitutes to model for them as they had no reservations about removing their clothes and they were readily available in the bohemian areas where the artists had their studios.

Sickert found inspiration in the bustle of the music halls and cafés, as had his French Impressionist friends whose style he had adopted. A basic knowledge of Sickert’s technique reveals that what might appear to be mutilations in the faces of his figures are simply the result of his spontaneous Impressionistic stylings and have no sinister meaning.

The inspiration for the series of morbid ‘Camden Town’ paintings was not the Whitechapel murders, but the murder of Emily Dimmock in 1907 which Sickert was familiar with, being a resident of the area at the time. The claim that Mary Kelly, the Ripper’s last victim, was the subject for this series of morbid paintings appears to have been yet another after-dinner yarn spun by Joseph Gorman Sickert, the creator of the equally fanciful royal conspiracy tale. Gorman claims to be Walter’s illegitimate son, but has offered no conclusive proof of his parentage.

Scenes of crime?

Walter Sickert’s obsession with the Ripper appears to have originated around the same time as his landlady had shared her suspicions regarding a medical student who had been her lodger at the time of the Whitechapel murders. Much has been made of the fact that Sickert was in the habit of dressing as the Ripper, but he was also known to dress up as other historical and fictional characters. It was an expression of his eccentricity and perhaps a habit left over from his earlier life as an actor.

A more serious accusation is that Sickert included details in his paintings which only the murderer would have known. Here we venture into the murky world of the conspiracy theorist who sees hidden meanings where none were intended, but there is nothing in Sickert’s paintings which has any direct bearing on the Ripper murders. Cornwell calls attention to the similarity between the positioning of the models in Sickert’s paintings and the position of the bodies at the crime scenes, but Mary Kelly was the only victim photographed at the crime scene. The other women were photographed at the mortuary. As for Cornwell’s assertion that a pearl necklace worn by one of Sickert’s models was symbolic of blood droplets, the less said the better.

As for a motive, Cornwell claims Sickert was rendered sterile by the appearance of a fistula on his penis and so took his frustration out on prostitutes. But Sickert was a notorious ‘immoralist . . . with a swarm of children of provenances which are not possible to count’, commented his friend Jacques-Emile Blanche. And the fistula was mere family hearsay, according to his nephew John Lessore.

Sickert may have been an eccentric and later suffered depression but he was not a psychopath. As a letter to Jacques-Emile Blanche reveals, he did not have an all-consuming hatred of prostitutes. Quite the contrary. ‘From 9 to 4, it is an uninterrupted joy, caused by these pretty, little, obliging models who laugh and unembarrassingly be themselves while posing like angels. They are glad to be there, and are not in a hurry.’

Suspect science

The cornerstone of Cornwell’s case is that her team of forensic scientists discovered a sequence of mitochondrial DNA (mtDNA) on several ‘Ripper letters’ which matched DNA recovered from letters written by Sickert. The first problem with this assertion is that there is no proof that the letters received by Scotland Yard in 1888 were written by the Ripper. Quite the contrary. Various high-ranking police officials have stated that they believe the two most infamous letters, the ‘Dear Boss’ letter and the ‘Saucy Jack’ postcard, to be a hoax perpetrated by a journalist who had abused his access to inside information and was known to them by name.

The second problem with this particular line of inquiry is that many people have handled both the ‘Ripper’ and Sickert letters over the course of the past 125 years which, as any forensic expert knows, could have seriously compromised the evidence, rendering them practically useless for proving anything. In fact, the original nuclear DNA tests came back negative and Cornwell’s team were forced to rely on mtDNA testing which only suggested a possible link. However, mtDNA is a less rigorous test and many individuals can share a similar molecular sequence. These sequences are not unique. On Cornwell’s own admission, as many as 400,000 people might have shared that particular molecular pattern in Victorian England. Without a sample of DNA taken from Sickert himself or one of his direct descendants no conclusive link can be established and nothing can be stated for certain. For all we know Sickert might have used a sponge to moisten the stamps and seal the envelopes as was a common practice at the time or, as is suspected, a servant might have posted his letters.

In total, 600 letters purporting to be from the killer remain in the police archives (many hundreds more were destroyed). So it is quite likely that with such a large sampling to choose from there is a good chance that one or two letters might have residual DNA that would be a reasonably close match to a specific suspect. But to identify and convict an individual, forensic science demands a positive match – a reasonable proportion of similar characteristics is not sufficient proof. Furthermore, the ‘Ripper letter’ which Patricia Cornwell claims contains both Sickert’s DNA and a watermark found in his own writing paper was never considered a genuine letter by students of the case. So the worst that could be said of Sickert is that he may have been guilty of writing hoax Ripper letters to the police, which does not make him the killer.

An artist abroad

But the most damning evidence against Cornwell’s imaginative theory is the fact that Sickert, it appears, was not in London during the time of the murders, but in France. On 6 September 1888, Sickert’s mother wrote describing how much Walter and his brother Bernhard were enjoying their holiday in St Valery-en-Caux, and on 16 September Jacques-Emile Blanche wrote to his father describing a congenial visit he had made to Walter there. On 21 September Walter’s wife Ellen wrote to her brother-in-law stating that her husband had been holidaying in France for several weeks.

Even allowing for the fact that Walter Sickert was wealthy enough to travel to and from England on the ferry as Cornwell suggests, it seems ludicrous even to consider the possibility that he absented himself from a holiday in France to return to Whitechapel to murder prostitutes whose company he evidently enjoyed and then add obscure clues in his paintings as a boast or confession. What it does prove is that Jack the Ripper continues to intrigue us and will no doubt do so for many more years to come.

A prime suspect – Francis Tumblety (1833–1903)

In 1993, while making a final inventory of his stock, retiring Surrey bookshop owner Eric Barton came across a bundle of letters relating to the Whitechapel murders. His initial feeling was that they were mere curiosities of the period and of as little value as the hundreds of hoax letters received by Scotland Yard during the autumn of 1888. He considered tossing them into the dustbin, but fortunately thought better of it and instead offered them to Suffolk police constable Stewart Evans, who had been a keen collector of Ripper memorabilia since his teens. Evans immediately saw the significance of one particular piece of correspondence written 25 years after the murders by Detective John George Littlechild to journalist George Sims, in which Littlechild named a prime suspect whom Evans had never heard of before, one whose activities and profile appeared to fit the Ripper profile perfectly – Dr Francis Tumblety. The Littlechild letter has been verified as genuine by forensic experts and no one is disputing its authenticity.

‘Knowing the great interest you take in all matters criminal, and abnormal, I am just going to inflict one more letter on you on the “Ripper” subject. Letters as a rule are only a nuisance when they call for a reply but this does not need one. I will try and be brief.

I never heard of a Dr D. in connection with the Whitechapel murders but amongst the suspects, and to my mind a very likely one, was a Dr. T. (which sounds much like D.) He was an American quack named Tumblety and was at one time a frequent visitor to London and on these occasions constantly brought under the notice of police, there being a large dossier concerning him at Scotland Yard. Although a “Sycopathia Sexualis” subject he was not known as a “Sadist” (which the murderer unquestionably was) but his feelings toward women were remarkable and bitter in the extreme, a fact on record. Tumblety was arrested at the time of the murders in connection with unnatural offences and charged at Marlborough Street, remanded on bail, jumped his bail, and got away to Boulogne. He shortly left Boulogne and was never heard of afterwards. It was believed he committed suicide but certain it is that from this time the “Ripper” murders came to an end.’

It was only by a quirk of fate that Tumblety, an Irish-American, had come to the attention of Inspector Littlechild, who was then investigating Irish Nationalist terror activities on the British mainland. Tumblety had no interest in politics. The only interest he served was his own. A rabid egomaniac and shameless self-publicist, he was wanted in the USA and Canada for posing as a doctor and peddling patent medicines of dubious merit, some of them allegedly lethal. The only known photograph shows him sporting a military-style uniform to which he was certainly not entitled.

Francis Tumblety

Morbid interests

The finger of suspicion begins to point towards Tumblety when one recalls that the assistant curator of a London pathological museum claimed that he had been approached by an American doctor who had expressed interest in purchasing women’s sexual organs and was prepared to pay £20 for each specimen. As Littlechild noted in his letter to Sims, the police considered Tumblety a ‘psychopathia sexualis’ rather than a sadist. He may have simply had a morbid interest in collecting such objects, but his unhealthy obsession nevertheless makes him a more likely suspect than the suicidal Druitt, the harmless imbecile Kosminski or the semi-invalid Sir William Gull.

Further clues push Tumblety’s name to the very top of the list of prime suspects in the Ripper killings. Littlechild’s correspondent, the journalist George Sims, had been in Whitechapel at the time of the murders and some years later was approached by a woman who suspected that her lodger may have been the ‘Whitechapel fiend’. She had never learnt his name, only that he claimed to be an American doctor. The lodging house in question was at 22 Batty Street, which runs parallel to Berner Street where Elizabeth Stride’s body was found and is just ten minutes’ walk from the other murder sites, less than five if one is running. At the height of the panic there were rumours that a bloodstained shirt had been discovered in a Whitechapel boarding house and that it belonged to a lodger who had been seen by his landlady returning late at night bespattered with gore.

Although the incident had been widely reported in the national and provincial press at the time, modern researchers have either overlooked it or chosen to dismiss it out of hand as yet another lurid story whipped up by Victorian reporters eager to keep the story spinning – but it has since been confirmed that the house at 22 Batty Street was under surveillance. It is thought that the suspect may have realized that he was being watched and taken up residence elsewhere – namely the Charing Cross Hotel, where a suspicious black bag was later abandoned by a guest who fled the country just after the Ripper murder spree had come to an abrupt end.

After the bag had been advertised in the lost property columns to no avail, the hotel handed it to the police who made an inventory of its contents. Inside they found clothes, cheque books and pornographic prints. The cheque books led the police to cable the American authorities requesting samples of Tumblety’s handwriting, suggesting that Tumblety may have been both the owner of the black bag and possibly even the mysterious Batty Street lodger. But just as the case appeared to be drawing to a conclusion the British press fell suspiciously silent and the police were equally unforthcoming. Had the press been pressured to drop the story to save Scotland Yard further embarrassment after having let their prime suspect slip through their fingers?

Chase across the Atlantic

The New York World revealed that Tumblety had actually been arrested by the London police on 7 November, two days before the last Ripper murder, and charged with gross indecency. But they couldn’t hold him for what was legally no more than a misdemeanour. As soon as he was released on bail Tumblety fled first to France then returned to the USA.

Scotland Yard must have realized the enormity of their error, for they rapidly despatched a senior detective and two colleagues across the Atlantic in hot pursuit.

They must have taken the possibility of Tumblety being the Ripper seriously, otherwise they would not have wasted such a valuable resource to recapture someone accused of a simple misdemeanour.

When Tumblety arrived in New York on 4 December 1888 looking ‘pale and excited’ according to contemporary accounts, he was met by two American detectives and surrounded by noisy newspapermen who wanted to know if he would confess to being Jack the Ripper. They had already questioned his family and acquaintances, most of whom unhesitatingly agreed that the man they knew could be capable of murder. But Tumblety evidently had no intention of being brought to account and fled his lodgings just two days after arriving in New York. Cheated of a good scoop, the most tenacious reporters left for Tumblety’s hometown of Rochester in upstate New York, where they tracked down his former neighbours. One remembered the young son of Irish immigrants selling pornography to the men working on the nearby canal. Another revealed that Tumblety used to work as a porter at the local hospital where, it is assumed, he picked up a grasp of medical knowledge which had given him a veneer of credibility.

Gruesome trophies

But Tumblety’s medical practice was not confined to peddling patent medicines. He is known to have attempted at least one crude abortion on a gullible prostitute and to have had a bizarre compulsion for collecting medical specimens. A gentleman acquaintance related a disturbing incident to an American reporter which may provide a motive for the hideous crimes Tumblety is accused of having committed in Whitechapel.

‘Someone asked why he hadn’t invited any women to his dinner. His face instantly became as black as a thundercloud . . . He said, “I don’t know any such cattle. But if I did I would, as your friend, sooner give you a dose of quick poison than to take you into such danger.” He then broke into a homily on the sin and folly of dissipation, fiercely denounced all women, especially fallen women. He then invited us into his office to illustrate his lecture, so to speak.’

The guests found themselves in a room brimming with a multitude of anatomical specimens preserved in glass jars including the wombs of ‘every class of women’. Could these have been trophies of his victims? And if so, what might have driven him to murder?

A focus for anger

Tumblety is thought to have been bisexual. It was only when he discovered that his wife had been a prostitute and that she continued to ply her trade during their marriage that he turned against all women and indulged in ‘unnatural vices’.

One would not expect a man with homosexual leanings to vent his anger on women, but rather on men, whom he might see as having ‘corrupted’ him. However, it is not inconceivable that Tumblety might have focused his anger on women in the belief that his wife’s rejection had forced him to seek the company of men.

And it is surely no coincidence that he committed his first indecency offence on the day of the first Whitechapel murder and that his subsequent offences coincided with the other killings. If he had been filled with self-loathing he might have attempted to exorcise his anger on a vulnerable target – the prostitutes who were substitutes for his wife.

He acquired a basic knowledge of abortions at the Rochester Infirmary, which would have enabled him to remove the organs within minutes and he is known to have collected such specimens. It is also possible that he might have used his rudimentary medical knowledge, respectable appearance and powers of persuasion to pass himself off as a doctor or even a back-street abortionist in the East End to obtain his victims’ confidence.

Whatever his methods, it is a matter of record that the Whitechapel murders began when he arrived in England and ceased shortly after he left. The accumulation of circumstantial evidence is compelling, but there is one final fact that might seem to seal the case against Francis Tumblety. When he died in St Louis in 1903, an inventory was made of his possessions. It included the expensive accessories one might expect such a flamboyant figure to possess – a gold pocket watch, jewellery and such. But there were two items which puzzled the nuns who had tended him during his final days: two imitation gold rings worth no more than $3 the pair. Could these have been the rings torn from the dead fingers of Annie Chapman?

The royal conspiracy

Journalist Stephen Knight titled his convoluted conspiracy study of the Whitechapel murders Jack the Ripper: The Final Solution. Subsequent research has proved that it was nothing of the kind. It was pure fiction, but for various reasons Knight’s dark romance captured the public imagination and has stubbornly refused to be displaced by the sordid, unvarnished facts.

The germ of Knight’s story took root in 1973 during research for a BBC docudrama which promised to provide a final solution to the mystery and reveal the identity of Jack the Ripper. Researchers initially approached an unnamed source in Scotland Yard who mentioned that there was a new theory going the rounds concerning a secret marriage between Prince Albert Victor, grandson of Queen Victoria, and an impoverished East End girl named Alice Mary Crook. The source suggested that the researchers should contact Joseph Sickert, who claimed to be the illegitimate son of the painter Walter Sickert and to be privy to the true story behind the Whitechapel murders.

According to Joseph Sickert, Prince Albert Victor – HRH the Duke of Clarence, known to his associates as ‘Prince Eddy’ – was in the habit of slumming in the East End with Sickert senior as his guide. During one particular sojourn among his less privileged subjects, he became infatuated with a lowly shop assistant, a girl by the name of Annie Crook. Annie was not only from a lower class but she was also a Catholic, which would mean that this Cinderella story could never have had a happy ending. But it was doomed the moment the Queen learned that the prince had fathered an illegitimate child and that he had married Annie in a secret ceremony in the hope of making their relationship official.

A dangerous scandal

If news of the relationship reached the newspapers it would cause more than a scandal – it could precipitate a revolution and bring down both the government and the monarchy. Cracks had already been appearing in the Empire’s foundations ever since Sir Charles Warren had ordered the merciless suppression of protestors in Trafalgar Square on ‘Bloody Sunday’, 13 November 1887. The unemployed were dossing down in Hyde Park and a mob had rampaged through the Mall throwing stones through the windows of gentlemen’s clubs. The Establishment was clearly a target for the disenfranchised, disenchanted and dispossessed. The Whitechapel Vigilance Committee and the so-called yellow press (popular papers) were demanding social reforms to make the streets safe from criminals in the wake of the Ripper killings. One more provocation and the working class might just take to the streets with clubs, bricks and broken bottles to set the eye of the Empire ablaze.

Something drastic had to be done to smother the story before a journalist caught a sniff. In desperation the Queen entrusted the situation to the Prime Minister, Lord Salisbury. According to Sickert, this loyal servant of the crown sent government agents to abduct the prince and his paramour from their Cleveland Street love nest and confine Annie in an asylum where no one would listen seriously to her tale of a royal plot. However, their plans for the child were thwarted by Annie, who had entrusted the child to the safekeeping of her friend, a prostitute by the name of Mary Kelly. At this point Jack the Ripper makes his entrance upon the stage in opera cloak and black silk top hat like a music-hall villain to despatch Kelly and the small circle of ‘working girls’ to whom she had entrusted the secret, these being Polly Nichols, Liz Stride and Annie Chapman. Then in the final act he tortures Mary Kelly, who dies refusing to reveal the whereabouts of the child.

Strange theories

A dark fairy tale indeed with obvious elements lifted from Cinderella and Snow White with Queen Victoria cast in the role of the wicked stepmother. But who was the Ripper? Sickert claims it was Sir William Gull, the Queen’s personal physician, who enticed the unfortunate women into his coach with bunches of grapes, disembowelled them in the carriage then dumped the bodies in the streets with the aid of a sycophantic servant, John Netley. As for the mutilations,they were perversions of a fictional Masonic ritual symbolizing the murder of Abrim Abif, the founder of the Freemasons, by three fellow masons, Jubela, Jubelo, and Jubelum – the ‘Juwes’ named in the Goulston Street graffiti.

The choice of murder sites also had Masonic significance. Mitre Square was reputedly the location of key Masonic lodges and the name itself had Masonic connotations – a mitre and a square being symbols in Masonic ritual. But this is yet another example of the selective choice of clues. There was also a suspicion that the murderer may have been a Jewish zealot who slaughtered his victims in a ritual sacrifice to his God during the Jewish sabbath. However, the sabbath begins at sunset on a Friday and ends at sunset on Saturday, and since several victims were killed in the early hours of Sunday morning this makes a nonsense of the whole idea.

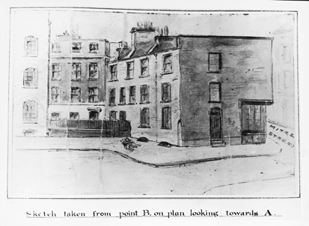

Police sketch of the crime scene at Mitre Square

The story gains currency

Incredibly, the BBC swallowed Sickert’s ridiculous story, partly because they could verify a few of the more salient points, such as the fact that a woman named Annie Crook had lived in Cleveland Street at the time and that she had given birth to an illegitimate daughter, but the main reason they endorsed the charade was simply because it made such a good yarn. And the thing about conspiracies is that the lack of physical evidence is no problem. Quite the opposite, since it can be argued that the conspirators destroyed everything that might implicate them. It is a revisionist historian’s dream, but has no basis in reality.

At this point author Stephen Knight picked up the story. He interviewed Sickert at length and expanded on the ‘evidence’ unearthed by the BBC, claiming to have obtained access to previously unpublished Scotland Yard files which were not to be open to the public until 1992. According to Knight the masons chose a scapegoat to cover their tracks, a young barrister named Montague Druitt, whom they murdered and offered his body in atonement for the crimes. But just when credulity has been stretched so thin it threatens to snap we are asked to believe that the baby girl survived and grew up to marry none other than Walter Sickert, the man who 20 years earlier had accompanied Prince Albert Victor in his sojourns into Whitechapel!

Montague Druitt whose family suspected him of being the Whitechapel murderer.

The real facts

Since the publication of Knight’s book researchers have produced documentation which proved that Annie Crook was not confined in an asylum but admitted herself to various workhouses and that during that time she had her baby, Alice Margaret, with her. Furthermore, on her marriage certificate she listed the father of the child as William Crook, who was her grandfather, which suggests her plight originated from incest, not from her involvement with an aristocrat.

As for Sir William Gull being unmasked as the Whitechapel murderer, he suffered a serious stroke in October 1887 which left him partially paralysed. Moreover, he was 72 years old at the time of the Ripper murders which not only doesn’t tie in with the witness descriptions, but also makes it unlikely that he would have had the strength to subdue his victims even allowing for the fact that one or two may have been the worse for drink. It also has to be pointed out that none of the residents living at or near the murder sites reported hearing a carriage rattling along the cobblestones in the early hours of the morning which would surely have aroused their suspicion.

And finally there is a further twist to the story that even Stephen Knight could not have come up with: shortly after the publication of Jack the Ripper: the Final Solution, Joseph Sickert confessed to the Sunday Times that he had fabricated the entire story.