Chapter 6: The Scotland Yard Files

Sir Melville Macnaghten wrote his influential and ultimately highly misleading memorandum on 23 February 1894 to refute newspaper reports that a disturbed young man named Thomas Cutbush had been identified by Scotland Yard as Jack the Ripper. No doubt the press were aroused by the fact that Cutbush had been a medical student and evidently mentally unstable. But as Macnaghten points out, a savage serial killer would be unlikely to be satisfied with prodding young women in the rear with a knife.

‘Confidential

The case referred to in the sensational story told in “The Sun” in its issue of 13th inst, & following dates, is that of Thomas Cutbush who was arraigned at the London County Sessions in April 1891 on a charge of maliciously wounding Florence Grace Johnson, and attempting to wound Isabella Fraser Anderson in Kennington. He was found to be insane, and sentenced to be detained during Her Majesty’s Pleasure. This Cutbush, who lived with his mother and aunt at 14 Albert Street, Kennington, escaped from the Lambeth Infirmary (after he had been detained only a few hours, as a lunatic) at noon on 5th March 1891. He was rearrested on 9th idem. A few weeks before this, several cases of stabbing, or jabbing, from behind had occurred in the vicinity, and a man named Colicott was arrested, but subsequently discharged owing to faulty identification. The cuts in the girls’ dresses made by Colicott were quite different to the cut(s) made by Cutbush (when he wounded Miss Johnson) who was no doubt influenced by a wild desire of morbid imitation. Cutbush’s antecedents were enquired into by C. Insp (now Supt.) Chris, by Inspector Hale, and by P.S. McCarthy C.I.D. – (the last named officer had been specially employed in Whitechapel at the time of the murders there) – and it was ascertained that he was born, and had lived, in Kennington all his life. His father died when he was quite young and he was always a “spoilt” child. He had been employed as a clerk and traveller in the Tea trade at the Minories, and subsequently canvassed for a Directory in the East End, during which time he bore a good character. He apparently contracted syphilis about 1888, and, – since that time, – led an idle and useless life. His brain seems to have become affected, and he believed that people were trying to poison him. He wrote to Lord Grimthorpe, and others, – and also to the Treasury, – complaining of Dr Brooks, of Westminster Bridge Road, whom he threatened to shoot for having supplied him with bad medicines. He is said to have studied medical books by day, and to have rambled about at night, returning frequently with his clothes covered with mud; but little reliance could be placed on the statements made by his mother or his aunt, who both appear to have been of a very excitable disposition. It was found impossible to ascertain his movements on the nights of the Whitechapel murders. The knife found on him was bought in Houndsditch about a week before he was detained in the Infirmary. Cutbush was the nephew of the late Supt. Executive.

Now the Whitechapel murderer had 5 victims – & 5 victims only, – his murders were (1) 31st August, ’88. Mary Ann Nichols – at Buck’s Row – who was found with her throat cut – & with (slight) stomach mutilation.

(2) 8th Sept. ’88 Annie Chapman – Hanbury St.; – throat cut – stomach & private parts badly mutilated & some of the entrails placed round the neck.

(3) 30th Sept. ’88. Elizabeth Stride – Berner’s Street – throat cut, but nothing in shape of mutilation attempted, & on same date Catherine Eddowes – Mitre Square, throat cut & very bad mutilation, both of face and stomach. 9th November. Mary Jane Kelly – Miller’s Court, throat cut, and the whole of the body mutilated in the most ghastly manner –

The last murder is the only one that took place in a room, and the murderer must have been at least 2 hours engaged. A photo was taken of the woman, as she was found lying on the bed, without seeing which it is impossible to imagine the awful mutilation.

With regard to the double murder which took place on 30th September, there is no doubt but that the man was disturbed by some Jews who drove up to a Club, (close to which the body of Elizabeth Stride was found) and that he then, “mordum satiatus”, went in search of a further victim who he found at Mitre Square.

It will be noted that the fury of the mutilations increased in each case, and, seemingly, the appetite only became sharpened by indulgence. It seems, then, highly improbable that the murderer would have suddenly stopped in November ’88, and been content to recommence operations by merely prodding a girl behind some 2 years and 4 months afterwards. A much more rational theory is that the murderer’s brain gave way altogether after his awful glut in Miller’s Court, and that he immediately committed suicide, or, as a possible alternative, was found to be so hopelessly mad by his relations, that he was by them confined in some asylum.

No one ever saw the Whitechapel murderer; many homicidal maniacs were suspected, but no shadow of proof could be thrown on any one. I may mention the cases of 3 men, any one of whom would have been more likely than Cutbush to have committed this series of murders:

(1) A Mr M. J. Druitt, said to be a doctor & of good family – who disappeared at the time of the Miller’s Court murder, & whose body (which was said to have been upwards of a month in the water) was found in the Thames on 31st December – or about 7 weeks after that murder. He was sexually insane and from private information I have little doubt but that his own family believed him to have been the murderer.

(2) Kosminski – a Polish Jew – & resident in Whitechapel. This man became insane owing to many years’ indulgence in solitary vices. He had a great hatred of women, specially of the prostitute class, & had strong homicidal tendencies: he was removed to a lunatic asylum about March 1889. There were many circumstances connected with this man which made him a strong “suspect”.

(3) Michael Ostrog, a Russian doctor, and a convict, who was subsequently detained in a lunatic asylum as a homicidal maniac. This man’s antecedents were of the worst possible type, and his whereabouts at the time of the murders could never be ascertained.

And now with regard to a few of the other inaccuracies and misleading statements made by “The Sun”. In its issue of 14th February, it is stated that the writer has in his possession a facsimile of the knife with which the murders were committed. This knife (which for some unexplained reason has, for the last 3 years, been kept by Inspector Hale, instead of being sent to Prisoner’s Property Store) was traced, and it was found to have been purchased in Houndsditch in February ’91 or 2 years and 3 months after the Whitechapel murders ceased!

The statement, too, that Cutbush “spent a portion of the day in making rough drawings of the bodies of women, and of their mutilations” is based solely on the fact that 2 scribble drawings of women in indecent postures were found torn up in Cutbush’s room. The head and body of one of these had been cut from some fashion plate, and legs were added to shew a woman’s naked thighs and pink stockings.

In the issue of 15th inst. it is said that a light overcoat was among the things found in Cutbush’s house, and that a man in a light overcoat was seen talking to a woman at Backchurch Lane whose body with arms attached was found in Pinchin Street. This is hopelessly incorrect! On 10th Sept. ’89 the naked body, with arms, of a woman was found wrapped in some sacking under a Railway arch in Pinchin Street: the head and legs were never found nor was the woman ever identified. She had been killed at least 24 hours before the remains which had seemingly been brought from a distance, were discovered. The stomach was split up by a cut, and the head and legs had been severed in a manner identical with that of the woman whose remains were discovered in the Thames, in Battersea Park, and on the Chelsea Embankment on the 4th June of the same year; and these murders had no connection whatever with the Whitechapel horrors. The Rainham mystery in 1887 and the Whitehall mystery (when portions of a woman’s body were found under what is now New Scotland Yard) in 1888 were of a similar type to the Thames and Pinchin Street crimes.

It is perfectly untrue to say that Cutbush stabbed 6 girls behind. This is confounding his case with that of Colicott. The theory that the Whitechapel murderer was left-handed, or, at any rate, “ambidexter”, had its origin in the remark made by a doctor who examined the corpse of one of the earliest victims; other doctors did not agree with him.

With regard to the 4 additional murders ascribed by the writer in the Sun to the Whitechapel fiend:

(1) The body of Martha Tabram, a prostitute, was found on a common staircase in George Yard buildings on 7th August 1888; the body had been repeatedly pierced, probably with a bayonet. This woman had, with a fellow prostitute, been in company of 2 soldiers in the early part of the evening: these men were arrested, but the second prostitute failed, or refused, to identify, and the soldiers were eventually discharged.

(2) Alice McKenzie was found with her throat cut (or rather stabbed) in Castle Alley on 17th July 1889; no evidence was forthcoming and no arrests were made in connection with this case. The stab in the throat was of the same nature as in the case of the murder of

(3) Frances Coles in Swallow Gardens, on 13th February 1891 – for which Thomas Sadler, a fireman, was arrested, and, after several remands, discharged. It was ascertained at the time that Sadler had sailed for the Baltic on 19th July ‘89 and was in Whitechapel on the night of 17th idem. He was a man of ungovernable temper and entirely addicted to drink, and the company of the lowest prostitutes.

(4) The case of the unidentified woman whose trunk was found in Pinchin Street: on 10th September 1889 – which has already been dealt with.

M.S. Macnaghten

23rd February 1894’

Frances Coles

The missing Ripper files

When the official police files were transferred from Scotland Yard to the Public Record Office in the 1980s several of the files itemized on the inventory were found to be missing. Fortunately, extensive notes had been made by various researchers shortly before they disappeared, preserving the names of a number of significant suspects who would otherwise have been overlooked.

A soldier suspected

One of the most promising is a report from the police at Rotherham dated 5 October, concerning a soldier with a violent hatred of women. Their informant, James Oliver, a former member of the 5th Lancers, was ‘firmly persuaded in his own mind’ that one of his former comrades was responsible for the Whitechapel murders.

The accused, Richard Austen, had been a sailor and was about 40 years old when the report was written. From the description of his appearance and behaviour, he seems a likely candidate for questioning, but the authorities were never able to trace him.

Oliver’s statement described him as:

‘. . . 5ft 8in, an extremely powerful and active man, but by no means heavy or stout. Hair and eyes light, had in service a very long fair moustache, may have grown heavy whiskers and beard. His face was fresh, hard and healthy looking. He had a small piece bitten off the end of his nose. Although not mad, he was not right in his mind, “he was too sharp to be right” . . . He used to sometimes brag of what he had done previously to enlisting in the way of violence . . . While in the regiment he was never known to go with women and when his comrades used to talk about them in the barrack room he used to grind his teeth – he was in fact a perfect woman hater.

He used to say if he had his will he would kill every whore and cut her inside out, that when he left the regiment there would be nothing before him but the gallows . . . Probably he would always be respectably dressed but more often the description of a sailor than a soldier.’

Oliver presumed he would be working at London Docks or on board ship and that he may have committed the murders shortly before embarking on a new voyage – which would account for the long gaps between murders. Oliver was convinced that if Austen could be traced his return to port would tally with the dates of the murders. ‘He always had revenge brooding on his mind,’ he said.

Oliver offered to identify Austen from a regimental photograph if one could be supplied and to look at the ‘Dear Boss’ letters to see if the handwriting matched that of his former comrade. However, no photograph could be found, but when facsimiles of the letters were sent down from London Oliver stated that the writing was very similar to Austen’s. Austen was never traced and the police had no choice but to abandon that line of enquiry.

Street Ballads

In famous London city in eighteen eighty-eight

Four beastly cruel murders have been done

Some say it was Old Nick himself or else a Russian Jew

Some say it was a cannibal from the Isle of Kickaiboo

Some say it must be Bashi-Bazouks

Or else it’s the Chinese

Come over to Whitechapel to commit

Such crimes as these.

’As anyone seen him? Can you tell us where he is?

If you meet him, you must take away his knife

Then give him to the women, they’ll spoil his pretty fiz,

And I wouldn’t give him tuppence for his life.

Now at night when you’re undressed and about to go to rest

Just see that he ain’t underneath the bed

If he is you mustn’t shout but politely drag him out

And with your poker tap him on the head

Eight little whores, with no hope of heaven,

Gladstone may save one, then there’ll be seven.

Seven little whores beggin’ for a shilling,

One stays in Henage Court, then there’s a killing.

Six little whores, glad to be alive,

One sidles up to Jack, then there are five.

Four and whore rhyme aright,

So do three and me,

I’ll set the town alight

Ere there are two.

Two little whores, shivering with fright,

Seek a cosy doorway in the middle of the night.

Jack’s knife flashes, then there’s but one,

And the last one’s the ripest for

Jack’s idea of fun.

Dr Winslow’s accusation

The following press cutting from the New York Herald dated September 1889 was evidently considered worthy of serious investigation as it had originally been preserved in the now missing police files by Chief Inspector Swanson, who subsequently interviewed Dr Forbes Winslow in an attempt to verify the story. Fortunately someone had the presence of mind to photocopy it before both the press cutting and the file containing Swanson’s notes went missing in the 1970s.

‘The Whitechapel Murders

A report having been current that a man has been found who is quite convinced that “Jack the Ripper” occupied rooms in his house, and that he had communicated his suspicions in the first instance to Dr Forbes Winslow, together with detailed particulars, a reporter had an interview with the doctor yesterday afternoon on the subject.

“Here are Jack the Ripper’s boots,” said the doctor, at the same time taking a large pair of boots out from under his table. “The tops of these boots are made of ordinary cloth material, while the soles are made of indiarubber. The tops have great bloodstains on them.”

The reporter put the boots on and found they were completely noiseless. Besides these noiseless coverings the doctor says he has the Ripper’s ordinary walking boots, which are very dirty, and the man’s coat which is also bloodstained.

Proceeding, the doctor said that on the morning of Aug. 30 a woman with whom he was in communication was spoken to by a man in Worship Street, Finsbury. He asked her to come down a certain court with him, offering her £1. This she refused and he then doubled the amount, which she also declined. He next asked her where the court led to and shortly afterwards left. She told some neighbours and the party followed the man for some distance. Apparently, he did not know that he was being followed, but when he and the party had reached the open street he turned round, raised his hat, and with an air of bravado said: “I know what you have been doing; Good morning.” The woman then watched the man [go] into a certain house, the situation of which the doctor would not describe. She previously noticed the man because of his strange manner, and on the morning on which the woman Mackenzie was murdered (July 17th) she saw him washing his hands in the yard of the house referred to. He was in his shirt-sleeves at the time, and had a very peculiar look upon his face. This was about four o’clock in the morning.

The doctor said he was now waiting for a certain telegram, which was the only obstacle to his effecting the man’s arrest. The supposed assassin lived with a friend of Dr Forbes Winslow, and this gentleman himself told the doctor that he had noticed the man’s strange behaviour. He would at times sit down and write 50 or 60 sheets of manuscript about low women, for whom he professed to have great hatred. Shortly before the body was found in Pinchin Street last week the man disappeared, leaving behind him the articles already mentioned, together with a packet of manuscript, which the doctor said was in exactly the same handwriting as the Jack the Ripper letters which were sent to the police. He stated previously that he was going abroad, but a very few days before the body was discovered (Sept. 10) he was seen in the neighbourhood of Pinchin Street. The doctor is certain that this man is the Whitechapel murderer, and says that two days at the utmost will see him in custody.

He could give a reason for the head and legs of the last murdered woman being missing. The man, he thinks, cut the body up, and then commenced to burn it. He had consumed the head and legs when his fit of the terrible mania passed, and he was horrified to find what he had done. “I know for a fact”, said the doctor, “that this man is suffering from a violent form of religious mania, which attacks him and passes off at intervals. I am certain that there is another man in it besides the one I am after, but my reasons for that I cannot state.”

Chief Inspector Swanson wasted no time in interviewing Dr Winslow and discovered the identity of the man with the religious mania. He was named as Mr Bell Smith, a Canadian who had been lodging with Mr and Mrs Callaghan of Victoria Park, who were friends of Dr Winslow.

The Callaghans had become suspicious of their lodger after he had stayed out until 4am on 7 August, the night of Martha Tabram’s murder. Later that day they discovered bloodstains on his bedclothes and noted that he had soaked his shirts in his room, presumably in an attempt to eradicate incriminating stains. The Callaghans regarded their eccentric guest as ‘a lunatic with delusions regarding women of the streets’, especially those in the East End. The Callaghans confirmed that their lodger’s handwriting was an exact match for the Ripper letters which had been widely circulated and published in the press. During his interview with Dr Winslow, Swanson obtained a description of Bell Smith from a letter written by Mr Callaghan to the doctor.

‘He is about 5ft 10in in height . . . hair dark, complexion the same, moustache and beard closely cut giving the idea of being unshaven . . . he appeared well conducted, was well dressed and resembled a foreigner, speaking several languages. [He] entertains strong religious delusions about women, and stated that he had done some wonderful operations. His manner and habits were peculiar. Without doubt this man is the perpetrator of these crimes.’

Incredibly, no further information is known about this promising line of inquiry and the trail ends with Swanson’s summation of the information received from Callaghan and a note regarding the fact that Inspector Abberline has no record of Dr Winslow’s accusation.

The police files

During the investigation police officials were discouraged from giving interviews to the press, but after the Ripper files were closed in 1892 various officers published their memoirs and talked openly to journalists of their suspicions regarding the known suspects.

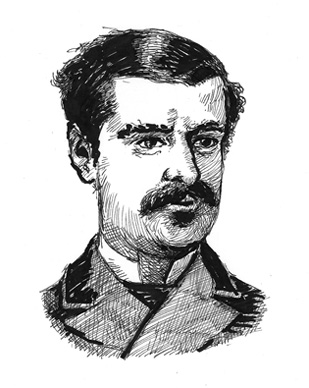

Metropolitan Police Inspector Frederick Abberline

In 1903 Abberline admitted that ‘Scotland Yard is really no wiser on the subject than it was fifteen years ago’. But the same year he reputedly told the Pall Mall Gazette that he personally had suspected convicted murderer Severin Klosowski (alias George Chapman) of being the Ripper: ‘I cannot help feeling that this was the man we struggled so hard to capture fifteen years ago.’ In a letter to Sir Melville Macnaghten written around the same time, he remarked, ‘I have been so struck with the remarkable coincidences in the two series of murders, that I have not been able to think of anything else for several days past.’ He noted the salient fact that his suspect ‘arrived in London shortly before the murders began, and then they stopped after he went to America. He had studied medicine and surgery in Russia, and the series of murders was the work of an expert surgeon.’ He felt it pertinent to add that Klosowski was known to have attacked his own wife with a long-bladed knife after they had emigrated to the USA.

In another interview he dismissed the rumour that Kosminski had been identified as the perpetrator, saying, ‘It has been stated in several quarters that “Jack the Ripper” was a man who died in a lunatic asylum a few years ago, but there is nothing at all of a tangible nature to support such a theory.’ He was equally dismissive of the case against Druitt. ‘Soon after the last murder in Whitechapel the body of a young doctor was found in the Thames, but there is absolutely nothing beyond the fact that he was found at the time to incriminate him.’

Sir Robert Anderson

In his autobiography, The Lighter Side of My Official Life, Anderson, who was Assistant Commissioner of the CID at the time of the murders, confidently asserted that ‘in saying that he was a Polish Jew I am merely stating a definitely ascertained fact’, adding, ‘One did not need to be a Sherlock Holmes to discover that the criminal was a sexual maniac of a virulent type; that he was living in the immediate vicinity of the scenes of the murders, and that if he was not living absolutely alone, his people knew of his guilt and refused to give him up to justice . . . I will only add that when the individual whom we suspected was caged in an asylum, the only person who had ever had a good view of the murderer at once identified him, but when he learned that the suspect was a fellow Jew, he declined to swear to him.’

It is understood that the suspect to whom he is referring is Kosminski and that the reluctant witness was either Schwartz or Lawende.

Donald Swanson, Chief Inspector, CID, Scotland Yard

Swanson later confirmed that the suspect Anderson referred to ‘was sent to Stepney Workhouse and then to Colney Hatch and died shortly afterwards’, adding, ‘Kosminski was the suspect.’ But he does not say if he believes that Kosminski was the Ripper, only that he was a suspect.

Chief Inspector John George Littlechild

In 1913 Littlechild wrote privately to journalist George Sims revealing that a substantial dossier had been compiled on a dubious character by the name of Dr Francis Tumblety who remained ‘a very likely suspect’, but the file has mysteriously vanished from the archives at Scotland Yard.

He concluded the letter by saying that Sir Robert Anderson only ‘thought he knew’ who the killer was, which suggests that no one actively engaged on the case knew with any certainty.

Chief Inspector Littlechild

Assistant Chief Commissioner Sir Melville Macnaghten

Although Macnaghten did not arrive at the Metropolitan Police until June 1889 he familiarized himself with the details of the case and identified Druitt, Ostrog and Kosminski as likely suspects. In the Aberconway version of his famous memorandum he went further, expressing his preference for Druitt. In his memoirs Days of My Years, he speculated that ‘the Whitechapel murderer in all probability put an end to himself soon after the Dorset Street affair in November 1888, certain facts, pointing to this conclusion, were not in the possession of the police till some years after I became a detective officer.’

Inspector of Prisons Major Arthur Griffiths

In his official capacity Griffiths was in the habit of visiting Scotland Yard and sitting in on discussions between Macnaghten, Anderson and Littlechild, which led him to claim that he was privy to inside information on the Ripper investigation. In Mysteries of Police and Crime he confided, ‘The general public may think that the identity of Jack the Ripper was never revealed. So far as actual knowledge goes, this is undoubtedly true. But the police, after the last murder, had brought their investigations to the point of strongly suspecting several persons, all of them known to be homicidal lunatics, and against three of these they held very plausible and reasonable grounds of suspicion . . . Concerning two of them the case was weak, although it was based on certain colourable facts. One was a Polish Jew, a known lunatic, who was at large in the district of Whitechapel at the time of the murders, and who, having afterwards developed homicidal tendencies, was confined to an asylum.’ This is a clear reference to Kosminski.

Assistant Commissioner James Monro

Monro was not given to speculation. He prided himself on acting on the facts alone, but was so certain that he knew the identity of the Whitechapel murderer that he told his grandson, ‘The Ripper was never caught. But he should have been.’ It is believed that he had a private file that he left to his eldest son Charles, who in turn shared the contents with his younger brother, Douglas, who described the dossier as ‘a very hot potato’. Douglas advised his brother to burn it and to forget what he had read. Unfortunately, Charles did so, so we have no way of corroborating the story.

Inspector Edmund Reid

Reid, who took charge of the initial investigation after the murder of Martha Tabram, maintained that there were nine victims, the last being Francis Coles. In 1912 he gave his verdict on the case to Lloyd’s Weekly News, in which he said, ‘It still amuses me to read the writings of such men as Dr Anderson, Dr Forbes Winslow, Major Arthur Griffiths, and many others, all holding different theories, but all of them wrong . . . the perpetrator of the crimes was a man who was in the habit of using a certain public-house.’ Reid did not have a specific individual in mind, but he had formed an opinion of the type of man who when drunk would lead his drinking companion into a dark corner then ‘attack her with the knife and cut her up. Having satisfied his maniacal blood-lust he would go away home, and the next day know nothing about it’. It is thought that he based this belief on a sighting by a witness who had reported seeing a suspicious man with a knife in a public house, but there were so many reports of a similar nature that identification would have proven impractical.

Chief Superintendent Sir Henry Smith

In 1910 Sir Henry Smith, Chief Superintendent of the City of London Police, published his memoirs From Constable to Commissioner, in which he claimed that he had a serious contender for the Ripper murders in mind at the time of the Eddowes killing which no other officer had known about. ‘He had been a medical student . . . He had been in a lunatic asylum; he spent all his time with women of loose character, whom he bilked by giving them polished farthings instead of sovereigns. I thought he was likely to be in Rupert Street, Haymarket, so I sent up two men and there he was . . . polished farthings and all, he proved an alibi without a shadow of a doubt.’

With that lead having proven a dead end, he was forced to admit that ‘Jack the Ripper beat me and every other police officer in London . . . I have no more idea now where he lived than I had twenty years ago.’

City of London Police Officer Robert Sagar

Sagar was adamant that ‘We had good reason to suspect a man who worked in Butcher’s Row, Aldgate . . . There was no doubt that this man was insane, and after a time his friends thought it advisable to have him removed to a private asylum. After he was removed there were no more Ripper atrocities.’

The Ripper in the USA

Festering in the shadow of the Brooklyn Bridge on the dockside of lower Manhattan in the spring of 1891 were huddled rows of squalid flophouses to rival those in London’s East End. The patrons too were cut from the same threadbare cloth as their English counterparts. In the squalid compartments of the East River Hotel sailors and dockside labourers could bed down in the company of cut- throats, petty criminals and drug addicts for the princely sum of 25 cents a night. Room service was extra – for a few dollars a prostitute could be persuaded to turn a blind eye to the cockroaches and act as if the rough pawing hands of a stranger were a lover’s caress. But some of the customers liked to play rough and on the morning of 24 April the desk clerk staggered from Room 31, shaken to the core by what he had just seen.

A naked woman lay on the bed, a deep wound extending from the lower abdomen to the breast. She had been strangled then disembowelled and her entrails strewn over the bed. When the police arrived they discovered two deep wounds in her back in the form of a cross. There were rumours that certain organs had been removed. The similarity with the Whitechapel murders was self-evident and quickly seized upon by the newspapers.

‘The points of similarity between this crime and those attributed to “Jack the Ripper” are numerous . . . The murdered woman belonged to the lowest class of fallen women from whom “Jack the Ripper” always selected his victims . . . The same horrible act of disembowelment and mutilation which distinguished the Whitechapel atrocities was performed upon this unfortunate hag . . . There was the same abstraction or attempted abstraction of certain organs. The instrument used – a big bladed knife – is similar to the weapon used by the Whitechapel fiend . . . The district in which the murder was committed corresponds . . . to the Whitechapel district of London, especially in respect to the character of many of its inhabitants.’

Several boasted sources inside the New York police, who confided their fears that the Ripper had fled England and was now loose in the Lower East Side.

Eyewitness account

A preliminary investigation retraced the victim’s last known movements. Somewhere between 10.30 and 11.45pm on 23 April she had asked for a room for herself and her companion, a man about 30 years old, 172cm (5ft 8in) in height with brown hair, a brown moustache and a prominent nose. He was wearing a Derby hat and a cutaway coat. He was sullen and silent for the most part, but when he spoke he betrayed a distinct accent, although the main witness, a prostitute named Mrs Miniter, could not recognize from which country he originated.

There was no doubt concerning the victim’s identity, however. Her name was Carrie Brown, a 60-year-old widow of a wealthy sea captain and mother of three children who had succumbed to prostitution after falling foul of the demon drink. But in her younger days she had been an actress of some repute and was still given to quoting verse which had led to her being given the nickname ‘Old Shakespeare’.

Within three days Inspector Byrnes announced that he had a material witness, an Algerian known locally as ‘Frenchy’, and was now looking for his cousin who was known by the same soubriquet in connection with the killing. But shortly afterwards, Byrnes surprised both his colleagues and journalists by denying that he had named the Algerian as a suspect. The turnaround baffled reporters, who delighted in reminding their readers that it was Byrnes who had once boasted that he would not have allowed a serial killer to run rings around his men as the London police had done.

Inspector Byrnes’ mistake

A few days later Byrnes made another contradictory claim. He now identified the prime suspect as Frenchy No. 1, the man he had been holding as a material witness, whose real name was Ameer Ben Ali.

Frustrated journalists quickly became highly critical of the investigation and demanded, ‘Why was it that intelligent reporters did not see the bloody tracks leading across the hall from Room No. 31, the woman’s room, to Room No. 33, Frenchy’s room, or at least the marks of their erasure? And how was it that they had failed to notice that Room No. 33 had the appearance of a slaughterhouse, as Mr Byrnes says it had? In the opinion of the general public Inspector Byrnes must look a good deal further before he finds the real Jack the Ripper. Sympathy is entirely with Frenchy, and there is a general belief in his innocence. Byrnes must soon admit himself as badly baffled and as much at sea as was Scotland Yard during and after the London butcheries.’

Others hinted at the real motive behind the embarrassing volte face: ‘It is charged by the enemies of the Inspector that he is really prosecuting Frenchy to make good his word that a Jack the Ripper could not live here two days in safety.’

During the trial serious doubts were raised regarding Ali’s guilt. Reporters who had been on the scene the morning of the murder contradicted the official police version of events while police officers gave conflicting statements. Then it emerged that Ali had not occupied the room to which the mysterious blood trail had led, but incredibly the jury found him guilty nevertheless. He was to spend 11 long years in prison before a concerted press campaign forced the authorities to acknowledge serious misgivings regarding the validity of the evidence and order his release.

A credible suspect

Meanwhile Frenchy No. 2 had been traced and questioned and his connection with the Whitechapel murders revealed by the New York daily The World:

‘There is a man named “Frenchy” who answers the description of Frenchy No. 2, and who was arrested in London about a year and a half ago in connection with the Whitechapel murders . . . During the past two or three years this man has been crossing back and forth between this country and England on the freight steamers that carry cattle. He is noted for his strength and physical prowess . . . The sailors on the cattle ships tell horrible stories of his cruelty to the dumb brutes in his care. When one of these animals would break a leg or receive some injury that necessitated its slaughter, “Frenchy”, they say, would take apparent delight in carving it up alive while the sailors looked on. No one dared oppose him, his temper was so bad. When he was arrested on suspicion that he was “Jack the Ripper” he knocked down the officer who tackled him and made things very lively for half a dozen men before they got him under control.’

But just when it appeared that the American authorities had finally collared Jack the Ripper the suspect was released, despite having been positively identified as Carrie Brown’s sullen and silent companion by Mary Miniter. It appears that Inspector Byrnes had lost faith in her reliability after having learned that she was a dope addict.

The reporters, however, scented a scoop and were not so easily put off. They traced Frenchy No. 2 to a lodging house and even managed to persuade him to give them an interview. Could this be the one and only time we hear the voice of Jack the Ripper?

‘The night of the East River murder I passed in this lodging house . . .’ he began. ‘My name is Arbie La Bruckman, but I am commonly called John Francis. I was born in Morocco 29 years ago. I arrived here on the steamer Spain April 10 from London.’

In reply to a question concerning his arrest in London La Bruckman answered, ‘About 11 o’clock one night a little after Christmas, 1889, I was walking along the street. I carried a small satchel. I was bound for Hull, England, where I was to take another ship. Before I reached the depot, I was arrested and taken to London Headquarters. I was locked up for a month, placed on trial and duly acquitted. After my discharge the Government gave me £100 and a suit of clothes for the inconvenience I had suffered.’

This was contradicted by a subsequent news item which stated that La Bruckman had been in custody for a month on suspicion of being the Ripper and that he was later discharged. There had been no trial. If there had been, all England would have read about it.

Could it have been La Bruckman?

This may be the source of the story published after the murder of Frances Coles in February 1891. ‘A policeman who saw the unfortunate woman a short time before the murder said that she was talking to a man who looked like a sailor. The police searched all the cattle ships but found no reason to arrest anyone. Late in the evening, a man was arrested on the docks and locked up on suspicion.’

Although there may not have been sufficient physical evidence to arrest La Bruckman, it is known that the company he worked for, National Line, had cattle boats in dock at London ports on dates coinciding with the Whitechapel murders.

But the suspicion that La Bruckman knew more about the Carrie Brown murder than he admitted persisted. Further investigations by the tenacious journalists uncovered the following story.

The clerk at the Glenmore Hotel, near the murder scene, remembered being accosted by a man answering La Bruckman’s description on the night of the murder. The man, who was in an agitated state, had blood on his hands, his shirtfront and his sleeves. When the clerk refused to give him a room for the night, he asked if he could use the rest room in the lobby to clean himself up, but again the clerk refused. Had Inspector Byrnes pursued this line of inquiry he might have cleared up both the Carrie Brown murder and the mystery of Jack the Ripper, but for reasons known only to himself he chose to prosecute Ali the Algerian and allow La Bruckman to slip through his fingers.

Byrnes’ complacency should have been shaken by the discovery of another mutilated corpse just a month after Ali’s conviction, but perhaps he did not relish having his assumptions questioned. The Morning Journal had no such reservations. ‘Is It Jack’s Work?’ asked their headline the morning after the body of a 45-year-old prostitute had been fished out of the East River. It is a question that remains tantalizingly unanswered to this day.

On The Track

The summer had come in September at last,

And the pantomime season was coming on fast,

When a score of detectives arrived from the Yard

To untangle a skein which was not very hard.

They looked very wise, and they started a clue;

They twiddled their thumbs as the best thing to do.

They said, “By this murder we’re taken aback,

But we’re now, we believe, on the murderer’s track.”

They scattered themselves o’er the face of the land –

A gallant, devoted, intelligent band –

They arrested their suspects north, east, south, and west;

From inspector to sergeant each man did his best.

They took up a bishop, they took up a Bung,

They arrested the old, they arrested the young;

They ran in Bill, Thomas, and Harry and Jack,

Yet still they remained on the murderer’s track.

The years passed away and the century waned,

A mystery still the big murder remained.

It puzzled the Bar and it puzzled the Bench,

It puzzled policemen, Dutch, German, and French;

But ’twas clear as a pikestaff to all London ’tecs,

Who to see through a wall didn’t want to wear specs.

In reply to the sneer and the snarl and the snack

They exclaimed, “We are still on the murderer’s track.”

They remained on his track till they died of old age,

And the story was blotted from history’s page;

But they died like detectives convinced that the crime

They’d have traced to its source if they’d only had time.

They made a good end, and they turned to the wall

To answer the Great First Commissioner’s call;

And they sighed as their breathing grew suddenly slack –

“We believe we are now on the murderer’s track.”

(George Sims)