1924

428F

Vienna IX, Berggasse 191

4 January 1924

Dear Friend,

I have left so many of your friendly letters unanswered that today I am virtually delighted to have to write you about a factual matter. Though there is nothing pleasing about the fact itself.

For the psychoanalytic fund cannot be counted on at the moment. Apart from the devalued Marks, it contains a little over 20 pounds, which I beg to keep strictly secret. I would gladly have stepped into the breach myself, but for half a year I have had only expenditure and no income.

Because of the numerous Christmas visitors from Berlin, I have heard and talked a great deal about you recently. I was delighted to hear only good things about you, so your optimism is at least not unfounded. I declined all Christmas visits that were meant for me personally with the motivation that you yourself give; only my son Oliver was with us here with his young wife. I did not wish to postpone further making the acquaintance of my new dear daughter.

I am by no means without any symptoms or released from treatment, but I resumed my analytic work on the 2nd of this month and hope to be able to manage.

With cordial greetings and New Year wishes to you and your dear family,

Yours,

Freud

1. Typewritten and hand-signed letter, evidently dictated to Anna, who used a more modern orthography than the one Freud was accustomed to using (e.g. zahlreich and Motivierung instead of zalreich and Motivirung). The typewriter could not reproduce the German double-s (“ß”) and the Umlaute; the dots on the latter were inserted by hand.

429F

INTERNATIONAL PSYCHO-ANALYTICAL ASSOCIATION1 CENTRAL EXECUTIVE

Vienna

15 February 1924

Dear Friends,

It is not without astonishment that I have heard from various sides that the recent publications of our Ferenczi and Rank, I mean their joint work2 and that on birth trauma,3 have evoked unpleasant agitation in Berlin. Apart from that, I was directly asked, by someone in our midst,4 to express among you my opinion of the undecided matter in which he sees the germination of a split. Thus I am complying with his wish, do not interpret it as obtrusiveness; my purpose being rather to exercise as much restraint as possible and to let each of you to follow his way freely.

When Sachs was last here, we exchanged a few comments on the birth trauma and perhaps the impression that I discern in the publication of this work an oppositional movement or do not at all agree with its content stems from that. I think, however, that the fact that I have accepted its dedication should make this interpretation impossible.

The fact of the matter is this: The harmony among us, the respect you have so often shown me, should not disturb any of you in the free exercise of his productivity. I do not ask that in your writings you orientate yourself more towards whether I will like them rather than whether they have turned out in accordance with observation and your views. Complete agreement on all questions of detail of the science and on all newly broached themes among half a dozen people of different natures is not at all possible nor even desirable. The sole condition for our working together fruitfully is that no one leaves the common ground of psychoanalytic prerequisites, and of this we may be certain in the case of every individual member of the Committee. On top of this there is another circumstance that is not unknown to you and that makes me particularly unsuited for the role of a despotic and ever vigilant censor. It is not easy for me to feel my way into unfamiliar trains of thought, and I have as a rule to wait until I have found the connection with them by way of my own winding paths. So if you wanted to wait with every new idea until I can approve it, it would run the risk of growing quite old in the meantime.

My attitude towards the two books concerned, then, is the following. The joint work I value as a correction of my view of the role of repetition or acting out5 in analysis. I had still been afraid of them, and had regarded these incidents, you now call them experiences, as undesired failures. R.[ank] and F.[erenczi] draw attention to the inevitability of this experiencing and the good use that can be made of it. Otherwise the work can be recognized as a refreshing and subversive intervention into our present analytic habits. In my opinion it has the fault of not being complete, i.e. it does not set out in detail the changes of technique that are dear to the two authors, but only hints at them. There are no doubt various dangers involved with this deviation from our “classical technique”, as Ferenczi called it in Vienna, but that is not to say that they cannot be avoided. Insofar as questions of technique are concerned here, I think that both authors' attempt to find out whether it can be done otherwise for practical purposes is absolutely justified. Time will tell, after all, what will come out of it. In any case we must take care not to condemn such an undertaking as heretical from the start. However, certain doubts need not be repressed. Ferenczi's active therapy is a dangerous temptation for ambitious beginners, and there is scarcely any way to keep them away from such experiments. I will also make no secret of another impression or prejudice. In my illness I learned that a shaved beard takes six weeks to grow again. Three months have now passed since my last operation, and I am still suffering from changes in the scars. So I find it hard to believe that it is possible in a slightly longer time, 4–5 months, to penetrate even into the deep layers of the unconscious and bring about lasting changes in the psyche. Naturally, however, I shall bow to experience. Personally I will probably continue making “classical” analyses, because firstly I take hardly any patients, only pupils, with whom it is important that they should experience as much as possible of the inner processes—training analyses cannot be dealt with in quite the same way as therapeutic analyses—and secondly I am of the opinion that we still have a great many new things to discover and cannot yet allow ourselves to rely solely on our prerequisites, as is necessary with shortened analyses.

Now to the second, and incomparably more interesting, book, Rank's birth trauma. I do not hesitate to say that I regard this book to be very significant, that it has given me a great deal to think about, and that I have not yet formed my final opinion about it. What I clearly recognize is as follows: We have indeed long known and appreciated the womb phantasy, but in the position that Rank gives it, it takes on a much higher meaning and shows us all at once the biological background of the Oedipus complex. To recapitulate in my language: An instinct that desires to re-establish the former existence must be attached to the birth trauma. One could call this the instinct to seek happiness,6 understanding there that the concept “happiness” is mostly used in an erotic sense.

Rank now goes beyond psychopathology into the general human field and shows how people in the service of this instinct alter the outside world, while the neurotic in his phantasy spares himself this labour by going back via the shortest route to the mother's womb. If we add to Rank's view Ferenczi's idea that a man is represented by his genitals,7 one can for the first time get a derivation of the normal sexual instinct that fits in with our concept of the world.

Now comes the point at which, for me, the difficulties begin. The phantasized return to the mother's womb is beset by obstacles that cause anxiety; the incest barrier, where does that come from? Its representative is apparently the father, the reality, the authority, which does not allow incest. Why did they erect the barriers to incest? My explanation8 was a historical-social, phylogenetic one. I deduced the incest barrier from the prehistory of the human family and thus saw in the current father the real obstacle that erects incest barriers in the new individual too. Here Rank differs from me. He refuses to go into phylogenesis and lets the anxiety, which opposes incest, directly repeat the birth anxiety, so that, he says, the neurotic regression into oneself is inhibited by the nature of the birth process. This birth anxiety, he says, is transferred to the father, but he is only a pretext for it. Basically the attitude to the mother's body or genital is assumed to be a priori an ambivalent one. This the contradiction. I find it very difficult to decide here, nor do I see how one can easily succeed from experience, for in analysis we shall always come upon the father as the bearer of the prohibition. But that is naturally no argument. I must for the time being leave the question open. I can bring forward as a counter-argument also that it is not in the nature of an instinct to be associatively inhibited, as here the instinct to return to the mother would be by association with the fright of birth. Actually every instinct as a drive to re-establish a former state presupposes a trauma as the cause of the change, and so there could be no other than ambivalent instincts, i.e. instincts accompanied by anxiety. There is naturally a great deal more that could be said about this in detail, and I hope that the idea evoked by Rank will be the subject of numerous and fruitful discussions. But we are not faced with a coup d'état, a revolution, a contradiction of our certain knowledge, but an interesting complement the value of which should be recognized by us and by those outside our circle.

When I add that it is not clear to me how the premature making conscious of the transference to the doctor as a bond to the mother can contribute to the shortening of the analysis, I have given you a true picture of my position with regard to both the works in question.

So, I value them highly, in part acknowledge them already now, have my doubts and reservations to some parts of their contents, am expecting clarification to emerge from further consideration and experience, and would like to recommend all analysts not to make too hasty a judgement on the questions raised, least of all a negative one.

Forgive my prolixity, perhaps it will prevent you from rousing me to express my opinion on matters that you could judge just as well for yourselves.

FREUD m.p.

1. Circular letter to the members of the Secret Committee; typewritten on IPA stationery.

2. Ferenczi & Rank, 1924. The authors put forward that, instead of remembering, the repetition of infantile material should play “the chief rôle in analytic technique” (p. 4), although the repeated material should then gradually be transformed into remembering. This material should be consistently interpreted in its relation to the “analytic situation”. They also introduced the systematic method of setting “a definite period of time for completing the last part of the treatment” (p. 13).

3. Rank, 1924a. For Rank, the trauma of birth, experienced by the infant as separation from the mother, was the foundation and the core of the unconscious. Therapy thus consisted in subsequently bringing to a close the incompletely mastered birth trauma. The transference libido, to be analytically dissolved for both sexes, was in his view the maternal transference libido. Birth anxiety was seen as the root of any anxiety, intrauterine pleasure as the origin of any later pleasure.

4. Eitingon had written that these books had “acted like a bomb in the Committee”, particularly with Abraham, who would be “especially angered at the fact that nothing of [their] contents had been revealed in advance to the Committee”. Eitingon had asked Freud to intervene with a statement on the new theories (letter to Freud, 31 January 1924, SFC).

5. Agieren.

6. Glückstrieb.

7. Ferenczi, 1924[268].

8. In Freud, 1912–13a.

430A

Berlin-Grünewald1

21 February 1924

Dear Professor,

You hardly need to be assured that your letter made a deep impression on me too. It was, as everything else you write, a document that leaves an impression. I too owe you a debt of gratitude for it. What you say and the way you say it has made me revise once again my statement on the three books by Sándor and Otto.

The objections that Hanns raises in his letter2 accord with yours on the important points, dear Professor. Now Ernest's letter3 has arrived too and contains similar comments. I agree with all these objections; also with those that go beyond your criticism. But I am worried with regard to the implications of certain phenomena in the new books, and my concern has increased in weeks of constantly renewed self-examination. Your letter and the discussion I had yesterday with Hanns have reassured me somewhat on certain points. In advance: there is no question of an inquisition! Results of whatever kind obtained in a legitimate analytic manner would never give me cause for such grave doubts. Here we are faced with something different. I see signs of a disastrous development concerning vital matters of Ψα. They force me, to my deepest sorrow, and not for the first time in the 20 years of my ψα career, to take on the role of the one who issues a warning. When I add that these facts in question have robbed me of a good deal of my optimism with which I face the progress of our cause, you will be able to gauge the depth of my disquiet.

I have one request to make, dear Professor, which you must not refuse. Call a meeting of the Committee just before the Congress and give me the possibility of a free discussion. The time allowed for the necessary exchange of opinions should however not be too short. The confirmation of your agreeing to this plan would reassure me greatly.

Faithfully as ever,

Yours,

Abraham

1. There exist two hand-written versions of this letter, the one actually sent to Freud and an identical copy in which most of the words were abbreviated. Abraham probably kept a copy of this important letter for himself.

2. In his letter to Freud of 20 February, Sachs had criticized the lack of a clinical basis of Rank's theory, reducing the whole exposition to “an analogy” and the book to “a torso” (in Jones, 1957: p. 66).

3. In his circular letter of February 18, Jones had raised “the question of the ulterior tendencies of the work, particularly in the hands of either ambitious or reactionary readers”, and put forward the criticism “that many ideas…were expressed in too dogmatic and even dictatorial manner, with sweeping condemnation of every other possibility…. Such passages could easily have been softened, if they had been seen beforehand by any other member of the Committee” (BL).

431F

Vienna, Berggasse 19

25 February 1924

Dear Friends,1

I am delighted that my circular letter reassured you on some points. But obviously it did not reassure you on all of them. I am ready to do anything to bring about further clarification. Perhaps you will come earlier to Vienna, so that we can travel to Salzburg together and so use this travelling time also to continue the exchange of ideas. Jones has asked for a day of discussion in Salzburg to avoid having to come to Vienna. This must be taken into account. The day for further discussion can only be Easter Sunday.

Rank has been confined to bed, I have not seen him for a fortnight and have not been able to discuss anything with him.

As my letter showed you, I am still far from having a definite opinion, and am myself not free from an inclination towards a critical standpoint. But I should like to be told what the impending danger is that I do not see. The matter may be further clarified in the interval until we meet.

I am very sorry to think that your association [the Committee] would

disintegrate immediately after my disappearance, but in any case I am selfish enough to wish to prevent this as long as I am still here.

With cordial greetings,

Yours,

Freud

1. Circular letter to the Committee.

432A

Berlin-Grünewald

26 February 1924

Dear Professor,

I can scarcely tell you how much gratification your second letter gave me. Since I see that you are prepared to listen to criticisms even though they go beyond your own and concern persons who are particularly close to you, I begin once again to hope for a solution of the difficulties. Your words regarding the preservation of the Committee accord fully with my own ideas and intentions, and I therefore await further developments with somewhat greater confidence.

You, dear Professor, would like to know what dangers I mean. If I tell you, you may well shake your head and refuse to listen further to me. But it is no longer possible for me to keep them back, and I shall therefore state briefly what I intend to put before our meeting, giving full and detailed reasons for my opinion.

—After very careful study, I must see in the Entwicklungsziele as well as in the Trauma der Geburt manifestations of a scientific regression that correspond, down to the smallest detail, with the symptoms of Jung's renunciation of Ψα.

This was not easy to say. All the more glad I am to be able to add that I am not blind to the differences in personality: Sándor and Otto, with all their pleasant qualities, on the one side; Jung's deceitfulness and brutality on the other—I have by no means overlooked these. This must not prevent me, however, from stating that their new publications are a repetition of the Jung case, which I was initially loath to believe myself. This is the one great danger I can see! Two of our best members are in danger of straying from Ψα and will therefore be lost to Ψα. However, their turning away from what we have up to now called ψα method is closely connected with the signs of disintegration in the Committee, and this disintegration represents the second danger. The third one is the damaging effect on the ψα movement to be expected from the new books.

Before I continue, I must ask your forgiveness, dear Professor, if I have caused you pain just now when you are so much in need of friendly and encouraging impressions. How much I should like to be able to give you these today too! But I have no choice if I wish to protect you from worse to come. The discussion I intend for our meeting appears to me the only means of preventing what you yourself see coming: the disintegration of our most intimate circle. Already last autumn it nearly fell apart. I may say it was I in the first place who prevented this at the time. I now would like to use all my influence once again to avert these dangers I referred to, as far as is still possible. I promise you, dear Professor, in advance that it will be done on my part in a non-polemic and purely factual manner and only with the wish to serve you and our cause, which is identical with your person.

Do you remember that after the first Congress in Salzburg I warned you about Jung? At the time you rejected my fears and assumed that my motive was jealousy. Another Salzburg Congress is just around the corner, and once more I come to you in the same role—a role that I would far rather do without. If, on this occasion, I find you ready to listen to me despite the fact that I have so much to say that is painful, then I shall come to the meeting with a hope of success.

Another word on practical procedure! As I see it, we must put at the top of our agenda a question that involves the very existence of the Committee itself. So Ernest ought to be there from the very beginning. We should therefore be in S. somewhat earlier. As there has to be a meeting of the heads of groups on Sunday, we should reserve at least Saturday for our purpose. Thus I propose that we should meet on Friday, so as to be able perhaps to discuss already in the afternoon or evening of that day. If, dear Professor, that is not convenient to you for any reason, we should all come to Vienna; in this case Ernest too is prepared to make a detour via Vienna. We should then have to be in Vienna for noon on Friday at the latest, and Thursday evening would probably be better.

With cordial greetings,

Yours,

Karl Abraham

433F

Vienna, Berggasse 191

4 March 1924

Dear Friend,

You certainly made my heart heavy by the reawakening of old Salzburg memories. I reluctantly discern from your letter the opinion that it is not easy to discuss certain personal as well as factual differences with me. I know that that is what my opponents proclaim to the world, but my nearest friends should know better. Nor is there any reason for you to make any such assumption, because, though my personal intimacy with Rank and Ferenczi has increased because of geographical factors, you ought to have complete confidence that you stand no lower than they in my friendship and esteem.

I want to let you know that an apprehension of the kind that you expressed is not so far from my mind. When Rank first told me about his finding, I said jokingly: “With an idea like that, anyone else would set up on his own.” I think that the emphasis is on the “anyone else”, as you yourself admit too. When Jung used his first independent experiences to free himself from analysis, we both know that he had strong neurotic and selfish motives that took advantage of this discovery. I could then say with justification that his crooked character did not compensate me for his lopsided theories. Incidentally, I learn from a case that came to me from him that he has been tempted into tracing back a severe obsessional neurosis to the conflict between individualism and collectivism.

In the case of our two friends, the situation is different. We are, after all, confident that they have no bad motives other than those secondary tendencies involved with scientific work, the tendencies to make new and surprising discoveries. The only danger arising out of this is of falling into error, which is difficult to avoid in scientific work after all. Let us assume the most extreme case: if Ferenczi and Rank were to come right out with the claim that we were wrong to stop at the Oedipus complex. The real decision was with the trauma of birth, and one who has not overcome this will later also fail at the Oedipus complex. Then, instead of our sexual aetiology of neurosis, we should have an aetiology determined by physiological chance, because those who became neurotic would either have experienced an unusually severe birth trauma or would have brought an unusually “sensitive” organization to that trauma. Further, a number of analysts would make certain modifications in technique on the basis of this theory. What further damage would ensue? We could remain under the same roof with the greatest calmness, and after a few years' work it would become evident whether one side had exaggerated a valuable finding or the other had underrated it. That is how it seems to me. Naturally I cannot in advance refute the ideas and arguments that you want to put forward, and therefore I am in full agreement with the proposed discussion.

Now to the practical procedure, as you write. You want us to begin the discussion already on the Friday before Easter, for which there would be time until Sunday evening. Here I must try an objection. Two or two and a half days' discussion would be practically equivalent to a doubling of the time of the congress, and that is too much for my weakened capabilities. I must once again contradict your incurable optimism and point out that I really am no longer the glutton for work that I used to be. Efforts I should not have noticed before my illness are now clearly too much for me. I even doubt whether I shall be able to listen to all the 15 papers to be read at the Congress, and in a corner of my heart, to quote our Nestroy,2 there actually lurks a desire to be spared the whole bother of the Congress. I hope that by then my state of health will have extinguished this impulse, but it is quite certain that I shall not be able to read a paper or attend the meal. These two injured functions do not permit any exhibition.

I therefore think that all the free hours of Saturday will have to be sufficient to settle the matter. Our all meeting in Vienna is out of the question at Jones's urgent request to be spared the journey to Vienna.

Please be so good as to let our friend Sachs have a look at this letter, which is intended for him too, and let me conclude with the hope by the time of our date at Easter much of this business will have been cleared up and quietened.

With cordial greetings to you and your whole house,

Yours,

Freud

1. Typewritten.

2. Johann Nepomuk Nestroy [1801–1862], famous Austrian dramatist and actor.

434A

Berlin-Grünewald

8 March 1924

Dear Professor,

I knew that with my last letter I would cause you pain. I shall not try to describe how difficult it was for me to write all this. My doubts on how you would receive my revelations referred really only to the fact that I had once again confronted you with the necessity of having to listen to very serious criticisms of two who stand so close to you. Neither in my letter nor at any time previously have I suggested that it is difficult to discuss factual differences with you. My opinion is exactly the opposite.—I can only admire over and over again your readiness in this respect. Just as little have I ever felt myself slighted by you. On the contrary, at our meetings in the Harz and in Lavarone, I felt that you deemed me worthy of your very special confidence. It is 17 years, dear Professor, since I first met you, and in all these years I have always felt happy that I could count myself among those closest to you; and nothing has changed about this even today. I do not wish the slightest doubt about this to arise.

Concerning the factual aspect, I find it satisfying that my opinion and yours are not incompatible. When I speak in more detail in Salzburg, I hope we shall come to a full understanding. Wherever I see a possibility of convergence, I shall, as always, be glad to seize on it! I do not want to bother you any further today. There is only one point I wish to stress once again: I have no difficulty in assimilating a new finding if it has been arrived at along a legitimate psychoanalytic path. My doubts are not directed at the results achieved by Sándor and Otto but against the paths they took. These seem to me to lead away from Ψα, and my criticisms will refer solely to this.

I gladly agree that we should meet at noon on Saturday in Salzburg. My suggestion that we should meet a day earlier was not intended to prolong our debates by another day but, on the contrary, to have more time for rest in-between!

This letter will go first to Hanns, who will probably add a few lines.

In unaltered (and unalterable!) devotion,

Yours,

Abraham

435F

Vienna, Berggasse 191

14 March 1924

Dear Friend,

Please send me a visitor's ticket for the Congress in the name of A. G. Tansley.

Tansley is or was Lecturer of Botany at Cambridge, resigned his post, and is thinking of devoting himself entirely to psychoanalysis. A book of his, The New Psychology,2 which has also appeared in German translation, has done a great deal for the spread of psychoanalysis, although it shows him still in a phase of development prior to being completely an adherent. He is now in analysis with me for the second time, and I hope to make considerable progress with his convictions. He is a distinguished, correct person, a clear, critical mind, well-meaning and highly educated. Naturally I should also be glad if you would notice and honour him at the Congress.

With cordial greetings,

Yours,

Freud

1. Typewritten.

2. Tansley, 1920.

436A

Berlin-Grünewald

17 March 1924

Dear Professor,

A few quick words in reply to your letter which arrived today. Why so much fuss about a guest ticket for someone whom you recommend? It would really have been enough to give the name. I cannot send any tickets, because there are none as yet. One of these days a circular is going to the groups to say that the admittance of guests shall be regulated by the groups. Those admitted by them will simply come to Salzburg and receive there their guest ticket on the recommendation of the relevant group. This way we shall spare ourselves endless letter-writing. If, then, you want to introduce further guests, the way is very easy. The main thing is that Frau Dr Rank knows about it, for she has to see to accommodation!

I take the opportunity of assuring you, dear Professor, that this time the Congress will be much less tiring. The number of papers is much smaller, and some of them are very short. I believe that the morning sessions will last scarcely three hours. Do not worry, I am taking care that it will not be a bother to you, but a real satisfaction as regards scientific achievements!

Cordial greetings from house to house,

Yours,

Abraham

437F

Vienna, Berggasse 191

31 March 1924

Dear Friend,

This letter is to inform you of a possibility that you have perhaps not yet taken into account.

Since a possibly influenzal nasal catarrh at the beginning of this month, my health has progressively deteriorated so much that last Saturday and Sunday, for the first time in my whole medical career, I had to stop working over the weekend. The short visit to the Kurhaus in Semmering has done me conspicuous good, but precisely because of that there is a possibility that I foresee. Unless my general condition improves in a quite extraordinary way by Easter—your tried and tested optimism will immediately assume that it will, but I remain doubtful— then I shall not come to the Congress to Salzburg but will again go to that sanatorium, where I can obtain some recuperation to continue the most essential part of my work.

Thus in that case neither the meeting of the former Committee and myself nor the lecture in which you wanted to warn me of the impending dangers of the new movement would take place. I think you should get used to the idea of such a possible course of events, and I take it that there would be no way about it other than you communicating person to person with each other as it should really have happened in the first place. For to whatever extent your reaction to F.[erenczi] and R.[ank] may have been justified, quite apart from that, the way you set about things was certainly not friendly, and it has become completely clear on this occasion that the committee no longer exists, because the ethos that would make a committee of this handful of people is no longer there. I think that it is now up to you to prevent a further disintegration, and I hope that Eitingon, whom I expect here on the 13th, will help in this. It cannot be your intention by reason of this apprehension of yours to cause the tearing down of the Internationale Vereinigung and everything connected with it.

I am selfish enough to feel it an advantage that because of my frailty I am at least spared having to listen to and to form an opinion on everything connected with the new squabble. I am neither very pleased about this advantage nor about the situation from which it derives. As a cautious question-mark still hangs over my decision, I shall wait until the week before the Congress before letting you know definitely.

With cordial greetings,

Yours,

Freud

1. Typewritten.

438F

Vienna, Berggasse 19

3 April 1924

Dear Friend,

I promised to write to you again as soon as I had made up my mind. I am therefore now writing to let you know that I shall not be attending the Congress, but shall be on the Semmering also at Easter, seeking out the peace and the pleasure of good air that I have needed so urgently since my influenza. I am simultaneously informing Jones and Eitingon, who is expected in Merano.

With cordial greetings,

Yours,

Freud

439A

Berlin-Grünewald

4 April 1924

Dear Professor,

My first reaction to your letter which I received yesterday was deep regret that your health is troubling you again. I was particularly sorry— both for your sake and for the sake of us all—to hear that you think you may have to stay away from the Congress. My next thought was that the discussion before the Congress could be held among ourselves and, on your arrival, we could just report the result to you. You would thus be spared anything that might be detrimental to your health. If you agree to this suggestion, everyone else will as well. In the meantime, I shall not stop hoping that your indisposition will soon pass, so that we may after all expect you for the Congress itself.

Subsequently your letter expresses a distrust of me that I find extremely painful and, at the same time, strange. I had believed that the correspondence we had some time ago had been concluded in a satisfactory manner, and suddenly I must hear the most serious reproaches! I must however admit that your letter has not evoked even a shadow of guilt in me. It is easy for me, dear Professor, to show you that I am the victim of a lapse of your memory and that all your accusations rest on a displacement of facts in my disfavour.

Your main reproach is that I should have tried to obtain a communication person to person. By avoiding this, I had acted in an unfriendly way towards Sándor and Otto. This reproach would have been justified if I had written spontaneously to you, dear Professor, to tell you of my doubts. But the facts are exactly the reverse. You yourself on 15 February directed a long circular letter at us all, and each of us replied in his own way to it; I in my way, which I had after all the right to do. At your express desire, I then wrote more extensively. There was, therefore, no behaviour on my part that could give the impression of evading the others or of insinuation, but only a legitimate reaction to your circular letter! Therefore this “guilt” is already without basis.

The further lapse of memory on your part concerns the purpose of our meeting before the Congress. You write that I want to give a “lecture” in order to “warn” you. It is true that in two of my letters I expressed a warning; but the purpose of the meeting was, as I explained in detail in my letter, to have a free discussion among all of us in order to re-establish the unity of the Committee! You understood me correctly at the time and replied: “therefore I am in full agreement with the proposed discussion”. Only afterwards did a misinterpretation of my intention creep in, and now I appear as the disturber of the peace and even as the destroyer of the Committee.

So, now to this third point! Last year in San Cristoforo the Committee would certainly have fallen apart had I not kept it together. During those days I worked with all my devotion to preserve this institution, which is so important to me, and to save you, dear Professor, from seeing the disintegration of the Committee. You must also remember that in Lavarone I tried hard to clear up the differences and to mediate. We said good-bye to each other on the Postplatz in Lavarone, glad to have achieved that much at least; and now you say that I want to destroy the Committee? This again can only have been due to a blotting out in your memory of all that speaks in my favour. Your reminder that it is up to me to prevent the disintegration of the Committee does in fact perfectly correspond with what I considered my foremost task when I wrote my recent letters.

And finally: It cannot be my intention to cause the tearing down of the Internationale Vereinigung! I can truly say of myself, dear Professor, that in my 20 years' adherence to our cause there has never been one day of vacillation in my attitude towards it. I do not exaggerate if I state that I have devotedly worked on the organization of the Berlin Society as well as the overall Association. During the last few months I have borne practically the whole burden of preparation for the Congress, in the hope of making it particularly harmonious and giving you a particularly pleasant and encouraging impression. And I was quietly occupied with plans for the Vereinigung with which I wanted to please you at the Congress—and now you suspect me of wanting to dissolve the Vereinigung.

I am very well aware of what I have done! I have plainly put before you the existing dangers to Ψα, to the harmony among the closest circle, and to the whole cause. I knew how painful all this would be for you. But you also know from my letters how hard I found it to do this. And I added that I was exposing myself to a similar reaction from you as in the past, when I first drew your attention to unwelcome facts. You, dear Professor, vigorously dismissed that I should expect any kind of affective reaction, admitted that my doubts were not too far removed from your own, and agreed to my proposal for discussion. But now, four weeks later, the reaction is there after all!

I feel with all certainty: talking with you, dear Professor, would disperse your suspicions within a few moments. This solution is impossible at present. But I know well enough; you cannot misjudge my ethos and intentions indefinitely in this way. On the contrary, I am certain that one day you will change your opinion. For the moment, just the assurance once again that I shall approach a meeting, also if you do not take part in it, without any polemic intent. I reckon with the fact that at the meeting some of the Committee members will treat me with the same distrust as you. Disquiet stemming from very certain sources is readily directed against the man who honestly indicates these sources. But just because I am fully aware and conscious of having behaved with loyalty towards everyone, I can calmly face these reactions too. I continue to go along with my friend Casimiro and am therefore also now,

faithfully as ever,

Yours,

Abraham

440A

Berlin-Grünewald

5 April 1924

Dear Professor,

I hasten to send you the programme, which has just come from the press, with the most sincere wish that your health may allow you to take part in the proceedings. The limitation of the number of papers seems to me a fortunate circumstance from this point of view; this time there can scarcely be any question of a strain. I believe that by far the greater part of the papers will gratify by their quality. I consider that too as bonum felix faustumque1; may it mobilize in you all the psychic forces that may serve to overcome the indisposition!

Yours,

Abraham

1. After the Latin saying: “Quod bonum faustum felix fortunatumque sit” [“what should be good and favourable, lucky and salutary”].

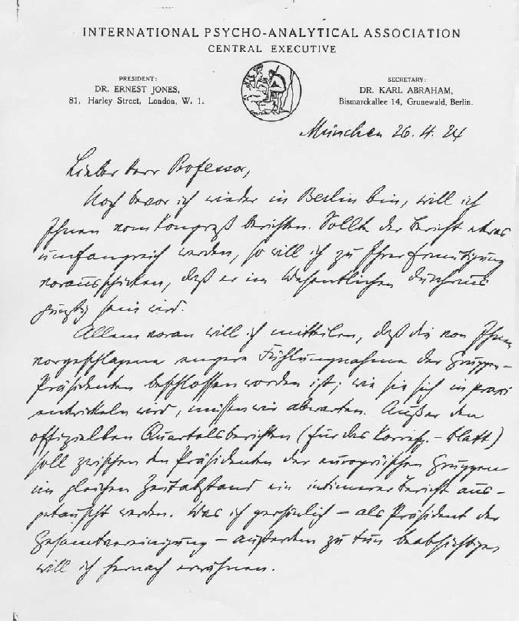

441A

INTERNATIONAL PSYCHO-ANALYTICAL ASSOCIATION CENTRAL EXECUTIVE

Munich

26 April 1924

Dear Professor,

Even before I am back in Berlin, I want to report to you about the Congress.1 If the report becomes somewhat extensive, I will tell you in advance, to encourage you, that in the essentials it is entirely favourable.

I will tell you first of all that the closer contact between the group presidents, which you suggested, has been decided; we must wait and see how it develops in practice. Apart from the official quarterly reports (for the Korrespondenz-Blatt), a more intimate report is to be exchanged at the same intervals between the Presidents of the European groups. What I also intend to do personally—as President of the General Association—I will mention later on.

Our more intimate circle agreed not to reinstate the Committee artificially. A repeated, thorough discussion took place between Sándor and me, after which we parted in old friendship with the agreement to send each other—calling in Max and Hanns—informal reports, and in every way to keep communication alive by exchanging letters. I should have liked to find a similar modus vivendi with Otto. Although that has not succeeded, I am still not giving up hope. The rather long separation because of his journey2 will perhaps level the ground, and if he sees after his return what—as I hope—will be there to be seen: that between the rest of us, especially between Sándor and me, there is no longer any disgruntlement, then this impression will surely convince Otto too that a new rapprochement is possible.

(continued, Berlin, 27 April)

The general harmony between the participants at the Congress was good. Criticism of the new literary publications remained within very moderate limits and was free from any polemical sharpness. As you probably know, America and India were not represented. Just shortly before the Congress I had a letter from Ermakov.3 Nobody, he said, could afford the journey from Moscow to Salzburg; perhaps Wulff4 might get State support. This must not have happened; at any rate, W. did not come. From Holland there was only van Emden; according to what he said, our Dutch colleagues are so badly off that they could not afford the journey. Switzerland was not represented in proportion to the number of members, but the most competent members were there: Frau Oberholzer,5 Pfister, Kielholz,6 Fräulein Fürst,7 Zulliger.8 Blum was missing; I would have been glad to make his acquaintance, as he seems the most promising to me. The English were well represented. The mutual understanding with them as well as among the Austrians, Hungarians, and Germans was very good indeed. The business session went off without a hitch. No sign of any danger for the continued existence of the Internationale Vereinigung.

Scientifically the general impression was that the Congress was on an excellent level. We were right to put Frau Dr Deutsch in the forefront of the first day; her work aroused general admiration. (In her Ψα with me she has come a great deal further; her work inhibition in particular has disappeared). James Glover was equally outstanding, then very competent were Hárnik9 and Dr F. Deutsch; only Liebermann dropped off badly. This first morning ended with my paper, which I will soon get ready for printing so as to send it to you.10

The symposium in the afternoon was of a similarly high standard. After Ernest's short introduction there followed the three detailed reviews,11 each in itself an excellent accomplishment, and after that a few brief words from Otto and Sándor.

On the 2nd day Frau Klein's paper on the technique of child analysis was an original achievement, and the rest was without exception good, as was also the 3rd day, on which Reik's paper was especially praiseworthy.12

I would much rather have told you all this personally, dear Professor. I would have been so glad to come to Vienna from Salzburg. But I heard from Fräulein Bernays that you were going home on Thursday evening. According to the strict travel restrictions I was absolutely bound to have crossed the Austrian–German border by Friday evening. That would have meant that I could only have seen you on Friday morning. And as I knew from you about your state of health, it would have been to put pressure on you if I had demanded to see you on the morning after your return. But to have waited longer in Vienna would have exposed me to a very high fine, i.e. at least 1,000 Goldmarks. It became easier for me to give up the visit to Vienna when I heard from various sides that you prefer at present to be left undisturbed. But you know, dear Professor, that at a sign from you I would come to Vienna. In the present circumstances I believe it is better to wait until I have a positive indication of that sort.

I would now like to tell you a few more things that, as I hope, will give you pleasure. While the Congress was still on, I managed to arrange a discussion with all German analysts present and with those who wished to become analysts, in order to bind to our organization interested persons living scattered over central and southern Germany. Around 1 October of this year a first meeting of German analysts will take place in Würzburg or another centrally situated town; this will bring about a collegial rapprochement and at the same time serve scientific purposes, giving temporary preference to questions of practical importance. In the course of time a second German Society is to develop from this. I have asked Landauer13 to undertake the preparations for this first meeting. He is the only one whose interest in the cause coincides with an unqualified personal devotion to you, dear Professor. I have also taken the opportunity, immediately after the Congress, of spending another day with Landauer and our wives on the Königsee, and I believe that in that way I have made our personal relationships much firmer.

The only group whose attitude to the Internationale Psychoanalytische Vereinigung seems to me to be somewhat disquieting is the Swiss one. Oberholzer, as chairman, stayed away, and his example must have affected others. I have now spoken to his wife about the situation. The resistances of the Swiss, which we have known about for a long time and believe we understand, are recently being rationalized through their rejection of the speculative direction of the last Congress and of everything that is not entirely free from the suspicion of being speculative. Now, apart from Frau Oberholzer's information, I can see other signs that the Swiss are sympathetic to my choice as President. As I shall be in Switzerland in the summer with my family—if they have not in the meantime put a death penalty on visits abroad—I plan to do something then to improve relations. You can see from this that I am not limiting my presidential activity to chairing the next Congress, but that I want to support the cause from the first day onwards.

Everything up to now, dear Professor, needs no reply. I need information from you on only one point, which is coming now, but a few dictated words on a card will be sufficient. Shortly before the Congress I received an invitation from New York, which, because it was inadequately addressed, wandered around for about six weeks. It comes from Dr Asch14 in New York, who is acquainted with one of my analysands. He refers to the immobilization of scientific activity and the need to attract younger forces following the Brill/Frink conflict. He says that there is a host of good young people who are being held back by this. If I were to come, I could be profitably occupied for about half a year with their analysis and other treatments and consultations. I heard only afterwards that Otto went directly from the Congress to America. My answer to Asch was a postponing one. I said I did not want to increase the difficulties by coming and would therefore like to know first what the others in N.Y. thought of this; in addition I must naturally be certain about the circumstances. It is not out of the question that I might make use of the invitation perhaps in November. I must now wait for information from N.Y. But in the meantime I would like to know, dear Professor, what you think of Asch, who, I believe, has been with you. Can one entrust to him a business like this, with its not inconsiderable risks? Do you know what the colleagues in N.Y. think of him? Do you see any contraindication to my visit, or do you even have positive reasons for it? Perhaps particularly as President I could do some good there. For the time being the whole thing is a perhaps for me. The possibility of getting to know America is a very great attraction indeed, but the whole plan is not definite yet, so we had better not talk about it. However, advice from you regarding the above questions would be useful. Many thanks in advance for it!

Another quick piece of information: in addition to the subject of my paper to Congress I am preparing something else, a study of the significance of the number seven in myths, customs, etc. I believe I have found something nice there.15

With all good wishes and the kindest regards from house to house

Yours,

Abraham

1. The Eighth International Psychoanalytic Congress took place in Salzburg, 21–23 April. Abraham was elected president and Eitingon secretary of the IPA. (See Abraham's report in the Zeitschrift, 1924, 10: 211–228.)

2. Rank left for New York immediately after the Congress. There, he lectured with great success on his new theories, i.e. before the Academy of Medicine, at Columbia University, at the New School for Social Research, and at the New York Psychoanalytic Society. On 3 June he was elected an honorary member of the American Psychoanalytic Association. Moreover, many leading New York analysts came to Rank for analysis or supervision.

3. Ivan Dmitrievitch Ermakov, m.d., director of the psychiatric clinic in Moscow. “The activity of Professor Serbsky at the University Clinic in Moscow led to the foundation of the ‘Little Friday Society’ in 1912. The war intervened, but in 1921 the movement took a new shape, namely, in the foundation of an institute for children under the age of three years under Professor Ermakov. This became the State Institute for Psychoanalysis. In 1921 the Russian Psychoanalytic Association was founded, Professor Ermakov was President and Dr Luria Secretary. The activity of the Institute was expanded and now includes lectures, seminars, the psychoanalytic child guidance clinic and laboratory, the psychoanalytic polyclinic and a specific ambulatorium for children” (Jones's report in Zeitschrift, 1924, 10: 226). The Russian Association had been acknowledged as a member society before the Salzburg Congress.

4. See letter 64A, 14 February 1909, & n. 2.

5. See letter 183A, 7 November 1913, n. 1.

6. Arthur Kielholz [1897–1962], m.d., long-term director of the Cantonal Psychiatric Clinic of Königsfelden, founding member of the Swiss Psychoanalytical Society [1919].

7. Emma Fürst, m.d., neurologist in Zurich, member of the Swiss Society.

8. Hans Zulliger [1893–1965], teacher at a primary school, a pioneer in psychoanalytic pedagogy, and a popular author and lecturer. He developed a form of child analysis centred on play therapy, using as few verbal interpretations as possible. He also developed two modified Rorschach tests.

9. Jenö Hárnik, m.d., of Budapest. In 1919 he had taken part in the psychiatric reform in public hospitals under the short-lived Hungarian “Council Republic”. In 1922 he emigrated to Berlin, became a member of the Society there, and, from 1926 on, was a teacher at the Berlin Institute. According to Charlotte Balkányi, Hárnik died in an insane asylum in Budapest.

10. The titles of the presentations: Helene Deutsch, “The Psychology of Woman in Relation to the Functions of Reproduction”; James Glover, “Notes on an Unusual Form of Perversion”; Jenö Hárnik, “The Compulsion to Count and Its Significance for the Psychology of the Representation of Numbers”; Felix Deutsch, “Psychoanalysis at the Patient's Bedside”; Hans Liebermann, “On Monosymptomatic Neuroses”; Karl Abraham, “Contributions of Oral Eroticism to Character Formation”. Abstracts in the Zeitschrift, 1924, 10: 212–214.

11. A discussion on “The Relationship between Psychoanalytic Theory and Practice”, with papers by Sachs, Radó, and Alexander (Zeitschrift, 1924, 10: 215–217).

12. Melanie Klein, “On the Technique of Early Child Analysis”; Theodor Reik, “The Creation of Woman. Analysis of the Account in the Genesis and in Related Scripts” (Zeitschrift, 1924, 10: 217, 223–224).

13. See letter 256F, 25 November 1914, n. 6.

14. Joseph J. Asch [b. 1880], m.d., member of the New York Society; in analysis with Freud in 1922 (9 December 1921, Freud & Jones, 1993: p. 446).

15. This project is discussed several times in the following letters but did not lead to publication.

442F

Vienna, Berggasse 19 1

28 April 1924

Dear Friend,

This letter, which is to congratulate you on the presidency, would have gone off several days earlier had not the “waves of the steamer” of the Congress thrown up on my shores so many visitors who could not be refused. I think with regret that you let yourself to be deterred from coming to Vienna and yet I must be selfish enough to regard it as a relief for which I thank you. The good Casimiro will have understood that this time it is not a matter of a passing indisposition on my part but of a new and badly reduced level of life and work.

I have heard with pleasure that the Congress passed off without any disturbing clashes, and I am very glad to acknowledge your services in this matter. As for the affair itself, I am, as you know, in an uncomfortable position. As regards the scientific aspect, I am in fact very close to your standpoint, or rather I am growing closer and closer to it, but in the personal aspect I still cannot take your side. Though I am fully convinced of the correctness of your behaviour, I still think you might have done things differently. On the question of nuance of attitude I agree with Eitingon.

Now let me wish you an active and successful period of office, and I send my greetings to you and yours with unruffled cordiality.

Yours,

Freud

1. Typewritten.

443A

INTERNATIONAL PSYCHO-ANALYTICAL ASSOCIATION CENTRAL EXECUTIVE

Berlin-Grünewald

29 April 1924

Dear Professor,

Our hotel in Salzburg has sent on to me all the letters for the participants in the Congress that arrived after our departure. Would you give the enclosed card to Prof. Tansley? Miss Newton1 is presumably staying in Vienna again. I am therefore also enclosing a letter to her. I would send it to Frau Dr Rank, but I know that she is not in Vienna.

With kind regards,

Yours,

Abraham

1. Caroline Newton [1893–1975], a social worker from Philadelphia. She had gone to Vienna in 1922, where she had analysis with Otto Rank (Ferenczi to Rank, 25 May 1924, Archives Judith Dupont) and became a member of the Vienna Society in 1924 [until 1938]. Participant at the Salzburg Congress, shortly after which she returned to the States. (Cf. Lieberman, 1985: pp. 254, 273, 275; Mühlleitner, 1992: pp. 234–235.)

444F

Vienna, Berggasse 19

4 May 1924

Dear Friend,

Your very conscientious report has completed my knowledge of events at the Congress in the most desirable manner. My heartfelt thanks for that. Also it did me a great deal of good to hear that real difficulties stood in the way of your coming to Vienna, so that its prevention did not depend on my will alone. It is very painful to me to think that of all people it was you, my rocher de bronce [sic],1 whom I kept away, while I had to see and speak to Emden, Jones, Laforgue,2 and Lévy.3

You must make a real effort to put yourself in my position if you are not to bear some ill-will towards me. Though apparently on the way to recovery, there is deep inside me a pessimistic conviction of the closeness of the end of my life, nourished by the never-ceasing petty torments and discomforts of the scar, a kind of senile depression centred around the conflict between irrational pleasure in life and sensible resignation. Accompanying this there is a need for rest and a disinclination for human contact, neither of which is satisfied because I cannot avoid working for six or even seven hours a day. If I am mistaken and this is only a passing phase, I shall be the first to confirm the fact and again put my shoulder to the wheel. If my forebodings are correct, I shall not fail, if sufficient time remains, to ask you quickly to come to see me.

The idea that my 68th birthday the day after tomorrow might be my last must have occurred to others too, for the city of Vienna, which usually waits until the 70th, has hastened to grant me the Bürgerrecht on that day.4 I have been informed that at midday on the 6th Professor Tandler,5 representing the mayor, and Dr Friedjung,6 a paediatrician and a district councillor, who is one of our people, are to pay me a ceremonial visit. This recognition is the work of the Social Democrats, who now rule the City Hall. Dr Friedjung shares my birthday but not, naturally, the year of birth.

The answer to your question is not difficult. Dr Asch was with me for a whole season, and I know him quite well. He is not an analyst at all, but a urologist. What standing he has with the analysts is easily told. None at all, it is only too clear that he is a pathological fool. His analysis with me was the most miserable you can imagine, without any trace of understanding, either analytic or simple (common sense).7 I did not want to hurt or expose him by sending him away, so I kept him on and waited, waited in vain to see whether the penny would drop. I have to say in his favour that he is a very kind-hearted, helpful person—because of inhibited sexual aggression—and therefore much loved. He wants to make everybody happy, meddles with everything, takes all kinds of things on in which he does not shrink from certain sacrifices; naturally he bites off more than he can chew and has to be set aside as utterly unreliable. Certainly he is not the man by whom you can let yourself be invited to America.

I would in any case be only sorry if you left the Association in the lurch in the autumn so as to make the trip8 to America. The prospects there are poor, the human material unusable. We took it amiss that Brill did not make more of the Association, but we owe him an apology, it is not possible to do anything more. Since Frink's misdemeanour9 I have given up all hope. I think I also know the young people who are waiting for the saviour: they are few and not worth much.

I have no doubt that you could get something done in New York if you could work there for two years, but nothing can be organized there in a few months, and as you are not prepared to do instantly boiling analysis, you could not do anything for the treatment of the sick either. Luckily the motive of improving your income, which could be the only excuse for going to America, is not necessary for you; you have too much you would have to give up in Berlin. You are not losing the chance to see America as an object of study; I have no doubt that sometime you will get to know the country on the basis of a more honourable invitation.—

After having been able to write during the worst period a few small things that you will see in the Zeitschrift,10 I am at present quite inactive and without ideas. I am moving further and further away from the birth trauma. I believe it will “fall flat”11 if it is not criticized too sharply, and Rank, whom I value because of his gifts, his great service to our cause, and also for personal reasons, will have learned a valuable lesson. Your reconciliation with Ferenczi seems to me to be particularly valuable as a guarantee for the future. The whole episode has had an unfavourable effect on my spirits in these difficult times too.

And now I send you my very cordial greetings and wish you and your wife and children a happy time that will justify your optimism.

Yours,

Freud

1. Rocher de bronze [rock of bronze]; after a dictum of the Prussian King Friedrich Wilhelm I.

2. René Laforgue [1894–1962], m.d., from Alsace, a central though controversial figure in the history of psychoanalysis in France (see de Mijolla, 1992; Roudinesco, 1982, 1986). Analysed by Eugenia Sokolnicka [1923], he was himself analyst of many influential figures in French psychoanalysis and mediated Marie Bonaparte's analysis with Freud. Cofounder of the Psychoanalytic Society of Paris [1926]. During the Nazi occupation he attempted to organize a psychotherapy group close to the “Aryan” Göring Institute in Germany.

3. See letter 339F, 29 May 1918, n. 5.

4. Bürger der Stadt Wien—freedom of the city of Vienna.

5. Julius Tandler [1869–1936], m.d., 1910 Professor of Anatomy, 1914–1917 Dean of the Medical Faculty. After the war Tandler was the Social Democratic City councillor for Health and Welfare. His name stands, with others such as Breitner, Glöckel, Seitz, and Speiser, for the social reforms in “Red Vienna”. After the civil war in February 1934 he was removed from office and spent his last years in the United States, China, and the Soviet Union.

6. Josef Karl Friedjung [1871–1946], m.d., paediatrician, Dozent for paediatrics at the University of Vienna, and social-democratic politician. Member of the Vienna Psychoanalytic Society since 1909; he was the only adherent of Adler's to stay in Freud's group after the break. Like Tandler, he was removed from office in 1934. In 1938 he emigrated to Haifa/Palestine. (Cf. Mühlleitner, 1992: pp. 1871–111; Handlbauer, 1992.)

7. Words in parentheses in English in original.

8. This word in English in original.

9. This word in English in original.

10. Probably Freud, 1924c, 1924e, and 1924d, the latter being a reaction to Rank's Trauma of Birth, although Freud eventually did not include some critical passages.

11. These words in English in original.

445A

Berlin-Grünewald

7 May 1924

Dear Professor,

Our letters crossed. In order to prevent this happening a second time, I postponed writing until I received your reply concerning America and only sent you a congratulatory telegram yesterday. Now you have rewarded me so generously with your two letters, particularly with the second, which actually arrived yesterday, making me feel as if it were my own birthday. I find it difficult to put into words my thanks for all the warmth and cordiality expressed in your letter. I feel infinitely relieved since I know that there is no factual discrepancy. For the last six months I have been very seriously worried. I cannot, naturally, in principle refute the possibility of having made an error in form. If I were to try to give a fuller explanation of my behaviour, I would have to go into many things that I have so far intentionally left untouched in our correspondence. I believe it is better to leave them unsaid; instead, I promise in future to show every consideration necessary in this far from simple situation.

I was glad, dear Professor, to receive your good wishes for my Presidency. If I on my part repeat my good wishes for your new year, I feel I am justified in being far more confident about the wishes than you are yourself. I can well imagine how the constant discomfort from the scar keeps painful thoughts alive. Even the necessity of having to think about one's health is a burden, and I never doubted the gravity of last year's illness. But on the other hand, six months have now passed since the operation without any new objective reasons for concern, and the latest news from my various informants—the most recent being Jones and Hitschmann—is that they found you better and more capable than expected. If my informants are correct and the discomfort from the scar is also gradually receding, I look forward to the immense pleasure of visiting you fairly soon and of congratulating you on your recovery. I am not to be easily put off from seeing the future in this light. As far as the Viennese are concerned, I give them two years to think of something even better for your 70th birthday than the honours of yesterday.

I am most especially grateful to you for the very detailed information on America; I was very touched by the exactitude with which you considered every detail. In the circumstances you describe—which up to now I did not know quite so exactly—I am no longer considering the project seriously. So I am staying at home, but I shall occasionally carry on the correspondence with your translator in Madrid,1 so that if possible I can give lectures in Madrid next spring. Another plan is to make contact now with internal medicine. I enclose a newspaper report2 that shows that soon a time will come when we can make an entry into these circles for our cause.

As the journals have not yet reached me, I have not yet read your latest article3; but I already knew about the various articles announced, and hope to read it soon. The first two volumes of the Collected Works,4 in full leather, stand resplendent in my room; they are a joy to look at.

I have already written about my work plans. At Deuticke's suggestion, I am preparing the 2nd edition of the Segantini.5 It makes me uneasy to think that this small booklet was not taken over by the Verlag along with so many others.

Tomorrow I am giving the first lecture in my course; after that I have a meeting with Max and Hanns. We want to meet regularly now.

Some time ago we rented a small flat for the summer months in Sils- Maria (Engadine), where we shall do our own housekeeping—that is, if we are allowed out of this country. Travelling difficulties are still very considerable.

I do not expect a reply to this letter, dear Professor!! Neither visits to your house nor correspondence should become a burden to you. I shall write again soon if there is anything to report.

Wishing you again all the best I can think of and with the most cordial greetings from house to house I am,

Yours,

Karl Abraham

1. Luis López-Ballesteros y de Torres.

2. Missing.

3. Freud, 1924e.

4. Volumes 4 and 5 of the 12-volume Gesammelte Schriften von Sigm. Freud, ed. Anna Freud, Otto Rank, and Adolf Storfer, in the Verlag.

5. Abraham, 1911[30], second, enlarged edition, 1925.

446A

Berlin-Grünewald

25 May 1924

Dear Professor,

This letter needs no reply. It is itself a reaction, one of joy to the good news I have heard through Lampl: that you will soon be released from surgical trusteeship and can enjoy your holiday in the mountains. I believe that you too feel heartened by this decree, and so I hope that this summer will for you and yours take place against a background of decreasing worries about health!

I am taking the opportunity to give you some good news from here. Especially our courses are making gratifying progress. Sachs has about 40 students for the “Kings' Dramas”; I have announced four lectures on “The Ψα of Mental Disturbances” and was amazed to get an audience of 50. The other courses too are—for summertime—well attended. The Society's activity is satisfactory. The consultation practice has equalled zero for some time, as nobody here has any money and the influx of foreigners is very much smaller since Berlin is no longer cheap. However we dare hope that this crisis will be over in time.

Yesterday I sent Reik a review of a work that appeared in Buenos Aires.1 In a prison the author has analysed quite deeply and, with much understanding, a man sentenced for murder! This sort of thing has to come to us from South America!

I have still heard nothing more from Asch in New York. Perhaps the best and simplest thing is if it is left at that.

I have read the short article on neurosis and psychosis with the greatest pleasure. Apart from all the other excellent points, which I do not need to mention, it was a delight to read something that has come from living experience and gives the reader such a unique feeling of security. And best of all, something is soon going to appear again—the pleasures of holidays!

Holidays—yes, if the authorities will allow it. I do not get the journey out to Sils-Maria free of charge for us. The “Gebühr” or rather “Ungebühr”2 would come to 2,000 Goldmarks and mean the failure of the whole plan, including appointments with patients. Apart from the fact that dogs have to be kept permanently on a leash; now human beings have to be tied up as well. There is a charming apartment waiting for us in Sils; the living-room is furnished entirely with antique carved built-in pieces, and there is also a garden, forest, water, and mountains. It would be a cruel sacrifice. But I am not giving up hope, and I shall insist to the limit.

Cordial greetings from house to house!

Yours,

Abraham

1. Beltrán, 1923; see Abraham, 1917[105b].

2. German play on words: Gebühr [fee], Ungebühr [impropriety]. [Trans.]

447A

Berlin-Grünewald

1 June 1924

Dear Professor,

This letter calls rather more for an answer than the previous one, but only when the opportunity arises, and you also need not give it yourself.

I have just heard from Sachs that you too are thinking of going to Switzerland, and also to Graubünden; he said that you are negotiating with Waldhaus-Flims. That would really be an ideal place, with the most beautiful forests and walks and, in addition, a lake that can certainly be deemed the equal of that of Lavarone. Should you not be able to decide on Waldhaus, I should like to offer to put at your disposal my special knowledge of Graubünden. I only mention at the moment that you might consider Klosters and Churwalden, both at the same elevation as Flims, and perhaps also Lenzerheide, which is 1300 m above sea level.

All these places can easily be reached from Sils-Maria, where we hope to go on 22 June. (But you know, dear Professor, that I shall not come if I have not been called for!). So prospects are opening to me that I welcome with great joy.

I should be very glad to know whether you will be in Switzerland, and where, and whether I can be of use to you in any way. Perhaps Fräulein Anna would tell me on a card what you have decided.

I am sure you will like it in Graubünden. The Flims region is particularly interesting from the point of view of nature and cultural history. Graubünden is my old love, and I hope it will meet with your approval.

With cordial greetings and many good wishes,

Yours,

Abraham

448F

Vienna, Berggasse 191

4 June 1924

Dear Friend,

It was very opportune for me that you produced such appreciative words for Waldhaus Flims. We booked there yesterday and want to arrive on 8 July. This time I am also taking with me a well-capitalized negro2 who will certainly not bother me more than that one hour in the day.

Being so near the Engadine, I count with certainty on seeing you and your family. You write that you hope to arrive in Sils-Maria on 20 June. If this were to be a slip of the pen, it would at least not be difficult to explain.

For good Casimiro the news that I am at least beginning to feel stronger and to be content with my defects. Perhaps my unsociability is also subsiding.

Cordially yours,

Freud

1. Typewritten.

2. When Freud began to practise, “[t]he consultation hour was at noon, and for some time patients were referred to as ‘negroes.’ This strange appellation came from a cartoon in the Fliegende Blätter depicting a yawning lion muttering ‘Twelve o'clock and no negro'” (Jones, 1953: p. 151).

449A

Sils-Maria, Engadine, Haus Gilly

30 June 1924

Dear Professor,

I was distressed to hear that you gave up your journey to Switzerland. 1 I have no idea where you will spend your holidays now, but must naturally agree with you that it is better not to be too far away from Vienna. Since travel restrictions in Germany have been lifted, I could perhaps come at the end of my vacation to wherever you are staying. I therefore hope to hear sometime where you will be spending the first half of August.

It is 18 years since I was in the Engadine and I am again as enchanted with it as on all previous occasions. Especially now in the spring there are more flowers in bloom here than anywhere else in the Alps. It is well before the season and therefore everything is rather empty, enabling us to enjoy to the full all the splendours of the alpine mountains. This time we have rented a small flat and brought our tried and trusted “mainstay” from Berlin, and we are looking after ourselves. Our flat is completely self-contained. The living-room is a typical Engadine room with a three-cornered bay window, panelled walls and ceiling, built-in furniture, etc., more comfortable than any hotel would ever have been; the bedrooms are large, light, and immaculately arranged.

Some daily analytic work—for the time being only one patient is here—keeps me in contact with my customary activity. Apart from that I am writing on the new edition of Segantini for Deuticke and am going over my Congress paper.2 If you, dear Professor, should wish to read it, I could send you the manuscript sometime (but you are not to say yes just to please me!).

I hope you are getting on quite well on the whole, despite your rather frequent difficulties, and I would be very, very happy to hear it confirmed by you yourself once more. Your last letter sounded so much more hopeful and positive and showed clearly that you had even got your sense of humour back. It is pleasant to hear news like that more often.

The new volume of the Collected Works reached Berlin after I had left, so that I shall not be able to read the two new articles3 until after I get back.

There is nothing else to report from the quietness of Sils-Maria. I wish you and your family very restful holidays and am, with cordial greetings from house to house,

Yours,

Karl Abraham

1. A communication of Freud's is evidently missing.

2. Abraham, 1924[99].

3. Freud, 1924e, 1925a [1924], in Volume 6 of the Gesammelte Schriften.

450F

Vienna, Berggasse 19 1

4 July 1924

Dear Friend,

There are circumstances in which one can be altruistic even in old age. So I take pleasure with you in the Engadine, although I myself cannot be there. I have too clearly recognized my dependence on my doctor's studio to put such a distance between him and me, and have rented the Villa Schüler, near the southern railway station in Semmering, from where I can comfortably get to Vienna and back in a day. The rent is so high that I need not think of a second sojourn anywhere else. So, if you want to come and see me in August, you need make no other journey. This time I too have brought a patient with me as hand-luggage who shall keep me in practice. My state of health has recently been showing ups and downs,2 according to whether the prosthesis, the nose or the ear chose to torment me more or less. I hope we shall now find a modus vivendi with each other.

If you wish to send me your Congress paper, it is exceedingly probable that I shall read it with the greatest interest. We intend to move on 8 July.

With cordial greetings to you and your house and best wishes for the summer,

Yours,

Freud

1. Typewritten.

2. These three words in English in original.

451A

Sils-Maria, Engadine, Haus Gilly

22 July 1924

Dear Professor,

If everything has gone according to your plan, you have now been enjoying your summer holidays for a fortnight, and I wish with all my heart that this time has been marred by as few troubles as possible. Thank you very much for your letter; I am sending you my manuscript today. I did not want to bother you with it earlier. Fortunately it is short, as the lecture lasted only half an hour, and so it will take up at the most half an hour of your time.

After our stay in Sils I shall arrange, dear Professor, to visit you there. But I ask you most earnestly to put me off honestly if my coming is not convenient for you. I shall let you know again nearer the time, probably somewhere around 10 August.

I recently had a few lines from Mrs Strachey, whom you kindly referred to me. I think she will probably come to me on 1 October.

We are very well here. Even after four weeks' stay Sils is still as splendid as it was on the first day. Wishing you very healthful and restful holidays, I am, with best regards from all of us,

Yours,

Karl Abraham

452F

Semmering1

31 July 1924

Dear Friend,

It is nice to hear that you can so thoroughly enjoy Sils-Maria. There is no question of my saying no to your coming to see me, if the small extra journey does not put you off. I am having a good rest here, I am no longer so withdrawn, and I am looking forward greatly to seeing you again. I have read your manuscript with the interest it deserves. Forgive me one small comment of secondary importance. You charge Adler with the responsibility for the connection between ambition and urethral erotism. Well, I have always believed that that was my discovery.2

Until we meet again, then! With cordial greetings to you and your wife and children,

Yours,

Freud

1. Typewritten.

2. This was corrected by Abraham in the printed version (1924[99]: p. 404).

453F

Semmering

22 August 1924

Dear Friend,

Ad vocem1: 7.

I am putting at your disposal an idea the value of which I cannot judge myself because of ignorance.

I should like to take a historical view and believe that the significance of the number 7 originated in a period when people had a system of counting in sixes. (Here ignorance sets in.) Then 7 was not the last of a series as it is now, in the week, but the first of a second series and, like all beginnings, subject to taboo. The fact that the initial number of the third series, that is to say 13, is one of the most eerie of all numbers would fit in with this.

The origin of my idea was a remark in a history of Assyria that 19 was also one of the suspect numbers, which was explained there with reference to the month that had passed by the equation 30 + 19 = 49, thus 7 x 7. However, 19 = 13 + 6, the beginning of a 4th series of sixes.

This system of sixes would thus be pre-astronomical. One should now investigate what is known of such a system, of which enough traces remain (dozen, three score, division of the circle into 360 degrees).

Moreover, it is strange how many prime numbers appear in this series:

1

7

13

19

25 is an exception, but then

31

37

43

49, which is again 7 × 7.

Mad things can be got up to with numbers. Be careful!

Cordially yours,

Freud

1. Latin: “as to the word (there is to remark)”—equivalent to the English use of re.

454A

Berlin-Grünewald

23 August 1924

Dear Professor,

I have been home for just a week1 and cannot wait any longer to send you at least a sign of life to express certain feelings. First of all, the great and incomparable pleasure of finding you, dear Professor, in spite of all you have gone through, so well, so sympathetic and capable, as I had scarcely dared hope from all written accounts. I left you expecting that the comfortable days spent on the Semmering would further contribute to your recuperation. And then I must thank you and all your family for all the kindnesses shown me! The days I spent with you made a particularly pleasant end to my holidays. I very much hope that your health will permit me to repeat my visit fairly soon.