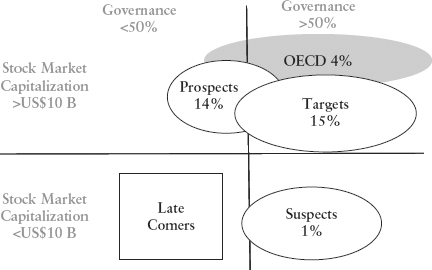

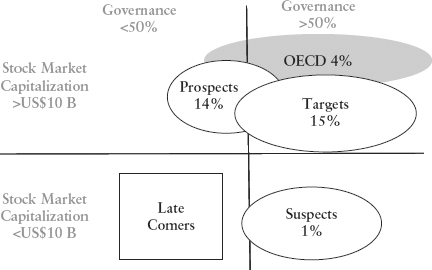

FIGURE 6.1 Market Capitalization (May 2011) and Governance Indicators 2010—Share of Global Stock Market Capitalization in Percent

Source: IMF, Worldwide Governance Indicators, author’s analyses.

We argue that a rigid classification into emerging and frontier economies largely based on stock market attributes is not a valid approach to selecting developing markets for investment. This may be an excellent guide for short-term traders, but not for investors. Below one year holding is speculative, one to three years is cash management, and above three years is investing. If we adopt these time parameters, investing in developing markets does not primarily depend on the stock market attributes or ease of trading in the short term. It depends on the longer-term outlook of an economy and more importantly on the longer-term prospects of a specific company or investment.

We argue that stock markets should be rated, not as listed companies, but as to their quality of trading environment for local and foreign investors. That would take care of the issue of trading environment. It would also take the exchange requirements out of the equation and focus investors on selecting specific investments and the analytical service providers on classifying markets according to their true economic potential.

The BRIC opportunity is a case in point. Except for the developed economies of the United States, the United Kingdom, Australia, France, Germany, Japan, and Switzerland and the economy of Hong Kong (significantly attributable to China), they are by far the largest stock markets. The size of the stock market could well be the consequence of the foreign investor BRIC focus and consequential capital flows. Nobody can argue the economic prowess of China and to a lesser degree India—they will dominate manufacturing and certain services for decades to come. However, the economies of Brazil and more so Russia do not figure in the same league other than by size and resources. On many scores of competitiveness, governance, or financial depth they simply do not match other emerging markets. Size of stock market should not constitute the primary selection criterion for all investors. Asset managers with large sums to invest necessarily need to look for the largest absorption capacity but they do so at their peril and need to recognize that they become a driver of the market as opposed to simply an investor.

The BRIC economies (Brazil, Russia, India, and China) are also a good example for the flawed application of country classifications. These markets are overappreciated when compared to their performance in the categories of rule of law, investment or business freedom, or global competitiveness. BRIC economies should not have a very special place because they cover a third of the world population or because China and India dominate certain sectors. They are clearly dominant developing markets, but not necessarily more attractive than a number of other economies.

There is no right or wrong answer for selection criteria of the most attractive or promising developing markets once the size argument becomes secondary. And there should be no wrong and no right answer. We cannot predict the future, and the event risk in emerging economies is significantly higher than in developed markets. More recently, in the United States and very recently in Europe, this tenet that event risk is higher in developing economies seems to be in question. We are, however, looking at one of several decades’ events in these markets; in emerging markets smaller events matter as much. Every government change, every economic policy reversal, and every change in conditions among neighboring or buyer economies can have significant consequences. Stock market volatility is not the right indicator since foreign capital compounds or even unlocks price volatility.

The responsibility of the asset manager or investor is in essence to select the most promising markets based on preferred economic attributes and then pick the right stocks. No country classification dominated by stock market or even macroeconomic evaluations can discharge this responsibility. Country classifications can only increase the moral hazard issue and foster an environment of window dressing by countries vying for membership in a coveted classification for increased capital flows. This does hardly anything to the attractiveness of companies or securities.

The rational investor will always prefer a lower risk investment within same return opportunities or a higher return investment with the same risk. The BRIC hype as a group seems to be a higher risk investment for higher returns. That is not a rational investment choice when alternatives—either same level of risk or same level of expected return—exist. Excess liquidity is not a valid base for making poor and concentrated investment decisions. Of course, the herding consequence of hype (in the worst-case scenario they generate euphoria or bubbles) masks the poor choices because capital flows sustain increases in market prices.

There seems hardly any reason why any investor would want to invest in an economy that operates as a bandit economy or on the fringes of governance. This is abundantly clear to the private equity investor who seeks contract and offshore solutions to insulate investments in high risk countries. The private equity investor takes willingly the risk of adverse framework conditions to achieve a superior return through active management and guidance of the investment company as well as protected corporate finance structures.

Yet across all private equity investments there is a 42 percent probability of failure (partial or total loss of the investment).1 Even if the failure probability is only about 30 or 21 percent for funds respectively buyout funds, the prevalence of high risk is part of the choice of the private equity investor. The largest and most experienced emerging market private equity investor, IFC, attests to this with its published performance and loss figures.2 Private equity makes an active and conscious trade–off decision between higher risk and higher returns that the stock market investor typically does not accept.

This is not the case with public equity since the element of active contribution and contractual protection is generally missing. If public equity investors allocate investments based on classifications that in turn are based mainly on stock market attributes, the underlying risk factors are ignored. The underlying risk factor is not only the company itself, which may well be properly managed, but the less than desirable framework conditions in which the company has to prosper. Therefore, public equity investors who value stock market attributes and some confidence in a proper purchase and exit process (with some degree of information and transparency) accept a level of risk not dissimilar to private equity investors. In a country with limited rule of law and high levels of corruption, no investment in which the investor has little or no influence, performs as well as it should or as can be expected from analyses. It is a fallacy to assume that because the stock market and foreign capital flows are somewhat benign, companies listed on the market operate in a transparent and orderly fashion. They do not and cannot if the environment is primarily informal. In Rome, do as the Romans.

More conceptually, every natural or artificial system eliminates system enemies and fosters system supporters. Otherwise the system gradually collapses. In economies with weak governance there is no choice but to accept the rules of market leaders and unwillingly become a bandit.

In any given country, investors therefore take the same framework risks but can deploy different tools to manage the risk. Private equity investors can influence and manage many more inherent risk aspects, but public equity investors can generally only sell if the investment does not develop according to plan. Thus the private equity investor has a higher probability of the same return than the public equity investor given the same risks. Therefore, the rational investor will not (not only) invest in public equity in a bandit economy where private equity alternatives exist.

As a consequence, the public equity investor must include as the primary market selection factor a higher level of governance to compensate for the lack of risk management tools. At a higher level of governance, the public equity investment with its advantages of transparency and requirements offers a true, lower risk alternative and the rational investor will select the low risk option given a similar level of expected returns.

This does not seem to be the case to date since the lion’s share of the emerging public equity investment goes into economies that are at the fringe of bandit economies simply measured by the governance indicators, the World Economic Forum indexes, the corruption index, or any other related measure. From a rational point of view, such investment is misguided. That does not mean that it cannot be sustained for years with a few ups and downs or that improving governance may solve the problem but the systematic risk remains higher than investors seem to factor into their assessments.

We suggest that some or many of the BRIC investments fall into that category. Not all sectors and not all industries and certainly not all companies across these economies have the same risk profile, but the systematic risk applies to all. To ignore this and to ignore solid governance base in which solid companies can prosper, is foolish.

Since we postulate that the relevant nature of developing economies lies in their degree of informality of economic interaction and dispute resolution, we consider governance or the rule of law, investment freedom and business freedom as the main indicator of investor attractiveness. These factors can be augmented by various global competitiveness aspects. Together they ultimately determine the success of a company and thus the return to the investor. They are the sufficient condition. Stock market attributes and size are a necessary but not sufficient condition.

The excess liquidity argument (essentially, size requirement) and transactional predictability is well taken. However, our proposed approach to evaluating and selecting emerging markets for investment only negates the size and classification arguments as the primary drivers or selection criteria.

We suggest one way of combining the size (stock market) and quality (governance) issues. This is a process and not a static list. There is no value in creating a list of currently attractive economies since this can change rapidly. Developing countries are prone to major shocks that can wreak havoc on a vulnerable economy.

The universe is composed of 86 stock exchanges in excess of US$1 billion or the vast majority of exchanges. Against each country we match the average of the World Bank governance indicators as the primary axis and define three workable universes based on two cutoff points: The stock market must have at least US$10 billion in market capitalization and governance must exceed 50 percent of global ranking (see Figure 6.1).

FIGURE 6.1 Market Capitalization (May 2011) and Governance Indicators 2010—Share of Global Stock Market Capitalization in Percent

Source: IMF, Worldwide Governance Indicators, author’s analyses.

Only the newer and less advanced members of the OECD are considered. They number nine and only Mexico does not meet the governance standard. Their combined market capitalization is just above 4 percent of global market capitalization. South Korea is by far the most prominent market; Mexico is second.

The category of targets includes many well established emerging markets of today and amounts to over 15 percent of global market capitalization. BRIC economies, except Brazil, are not included in this category. Hong Kong, Brazil, and Taiwan dominate.

The next prospects are similar in size, about 14 percent of global market capitalization and include China, India, and Russia. They, Russia in particular, need to develop their economic structure and governance to be considered main targets. That holds regardless of their global economic role. China is again a major exception because some of the indicators are much higher for key agglomerations of Beijing, Shanghai, and South China. Thus the urban and core industrial part of China probably makes the cut of 50 percent governance. The same argument could be applied to India and its core economic regions. It applies less so to Russia and Indonesia.

Future markets are much smaller, less than 1 percent of global market capitalization, but they can grow into decent sized markets given that their economic structure is largely developed with high to very high governance rankings. They may suit smaller or specialized asset managers and include: Malta, Cyprus, Barbados, Mauritius, Lithuania, Latvia, Botswana, Bulgaria, Ghana, Tunisia, and Trinidad. Their stock market capitalization range from US$1.3 billion to just under US$10 billion.

This categorization is dynamic and results in the country categories based on current data.

Overall about one third of world market capitalization is addressed (Table 6.1). However, these economies represent well more than half of world market capitalization outside the United States, Japan, and the United Kingdom.

TABLE 6.1 Market Selection: Governance and Market Capitalization (by size of market, May 2011)

| OECD “New” Economies | Targets | Prospects |

| 4.2% of World—9 markets | 15.3% of World—19 markets | 14.0% of World—18 markets |

| Mixed | >US$10B Mkt Cap, >50% Governance | >US$10B Mkt Cap, <50% Governance |

| Chile | Hong Kong | China |

| Czech Republic | Brazil | India |

| Estonia | Taiwan | Russia |

| Hungary | Singapore | Indonesia |

| Mexico | South Africa | Colombia |

| Poland | Malaysia | Philippines |

| Slovak Republic | Saudi Arabia | Peru |

| Slovenia | Turkey | Egypt |

| South Korea | Thailand | Argentina |

| Israel | Nigeria | |

| Qatar | Bangladesh | |

| UAE | Pakistan | |

| Kuwait | Vietnam | |

| Morocco | Ukraine | |

| Oman | Sri Lanka | |

| Bahrain | Kazakhstan | |

| Croatia | Swaziland | |

| Jordan | Kenya | |

| Romania |

Note: MSCI emerging and frontier as well as advanced markets in italic.

It is interesting to note that target markets based on a combination of reasonable stock market size (excluding all float and liquidity considerations) include all GCC (Gulf Cooperation Council) countries. These countries have decent legal systems and orderly economic processes that are continuously improving due to their resource incomes. Several are just considered frontier today. Their markets are mostly above US$100 billion; the exceptions are Oman and Bahrain.

The path for countries to join the target or prospect list is to improve governance and administrative systems rather than upgrading the stock market and leaving companies to fight on their own in a less than organized or structured economy. Investments in bandit economies are more speculative and higher risk than investments in solid economies, regardless of the growth rate, GDP capita improvement, resource endowment, or a host of other exciting macroeconomic data. Taking a higher risk needs to be rewarded and returns then must be commensurate. To date they are not. We all invest in about the same markets and the same major stocks and we all get about the same returns that do not compensate for the risks. Looking at structural fundamentals can diversify such a portfolio and position us for the future that is bound to happen along the lines of a dominance of a group-variety of emerging markets.

This, we argue, serves the investor better and certainly achieves better results over the long term.

In this context we must therefore accept the route of investing in smaller markets because it will take decades before several new emerging markets are anywhere near a size that allows them to compete with the big markets of today. By then, a good part of the potential performance will already be unlocked.

1. Tom Weidig and Pierre-Yves Mathonet, The Risk Profile of Private Equity (Luxembourg, 2004) (across 5,000 investments); Thomas Meyer and Pierre Yves Mathonet, Beyond the J-Curve (West Sussex: John Wiley & Sons, 2005).

2. www.Ifc.org.