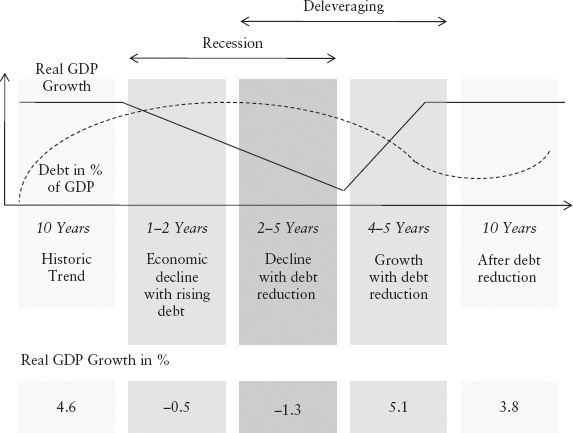

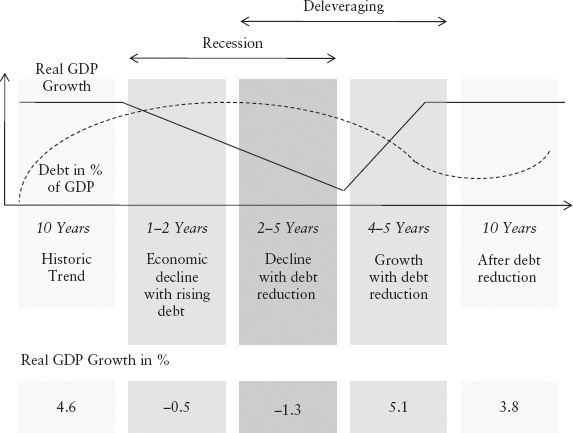

FIGURE 7.1 Structure and Time Line of a Crisis and Recovery

Source: McKinsey Global Institute, January 2010, Rising Star Research.

Emerging markets, led by the BRICs (Brazil, Russia, India, and China) are increasingly at the forefront of the media, typically on the subject of economic growth, resource endowment, and increasing exploitation of their growing political clout.

Yet, today there remains a valid debate about the permanence of the rise of emerging economies. Are we witnessing a fundamental shift in the global economic landscape or a short-term development? This issue is of fundamental importance to investors.

The present study comes to 10 straightforward conclusions to address the question of the stability of the rise of emerging economies and direction of future investments:

Stability

Direction

The financial crisis has helped clarify a number of macroeconomic challenges faced by industrial and emerging economies. Thus we study the current situation of industrialized economies to better understand the future of emerging economies.

For investors, it is important to assess the current starting position of global economies to establish whether the current trend toward emerging markets is short term or structural. To this effect, we will analyze the state of affairs in advanced economies and contrast these with developments and prevailing framework conditions in emerging markets. We subsequently develop an attractiveness ranking by geographical region (see Part One, Chapter 2).

No consideration of emerging markets is complete without differentiating between developed economies and emerging markets. Since the latest financial crisis, emerging markets have developed so independently that their growth actually supports the recovery of developed economies. Some emerging markets are creating employment in developed economies through direct investment and some emerging markets are creditors to developed nations. Emerging markets survived the financial crisis well and retain the strong competitive advantages that will allow them to grow sustainably and reduce the gap between them and developed economies. Their political influence may be increasing. Moreover, emerging markets include the majority of the global population that aspires to be economically independent.

All developed economies were seriously affected by the financial crisis. Public debt is rising and growth is moderate with little prospect of improvement. The consumer remains cautious and freedom of governments is restricted.

In 2008, the United States started an unprecedented set of economic measures and regulatory changes to the financial sector. The purpose of these economic measures was to support those economic sectors that were most affected by the recession. The regulatory changes were aimed at restoring the necessary liquidity to the financial system. At the same time, these measures sought to prevent the US consumer with “bad” home mortgages from becoming insolvent. In the meantime, these measures have partially expired.

The result has been a positive effect on preferred sectors, since for every US dollar spent by government, GDP increases by US$0.7.1 (By comparison, tax reductions of US$1.00 increase GDP on average by US$3.00.)

Measures to stabilize the financial system were rather half-hearted. While the World Bank and the IMF imposed rigorous conditions during the previous crises, the US measures sought to avoid any medium-term unpleasant consequences. The liquidity provided served primarily to improve the balance sheet situation of banks. Credit expansion has not taken place for either corporations or consumers. Past crises demonstrate that it will take a couple of years before debt reduction is completed and sustained growth returns, as shown in Figure 7.1.

FIGURE 7.1 Structure and Time Line of a Crisis and Recovery

Source: McKinsey Global Institute, January 2010, Rising Star Research.

As a consequence, the IMF assumes a slow recovery in the United States. The main reason lies in the central role of the US consumers. Their confidence is undermined by the crisis and employment conditions have not improved. The difference between potential and actual production remains significant. Low capacity utilization prevents employment recovery. Moreover, debt reduction has not taken place. The decline of real estate values predominantly affected low income households that typically consume the majority of their disposable income.

The key question now is how the United States can balance short-term measures to support recovery with medium-term credit rating. Government intervention needs to be reduced without endangering recovery, while all market participants must reduce their debt burden to strengthen the financial system.

The European Union is also recovering slowly. In particular, public debt concerns of individual member states impaired recovery before it got fully under way. Reforms to the pension and social security systems are urgently required, as is increased efficiency of administration. Equally in Europe, unprecedented rescue measures for the financial sector and selected member states have been taken. This has, however, reduced the credibility of the common currency and restricted fiscal freedom of governments.

Germany finds itself in a relatively strong position as exports are increasing, although traditional trade partners are growing slowly. The current export boom is largely due to emerging markets that require quality capital goods. This may not be sustainable since trade with these economies is relatively low when compared to Germany’s traditional trade partners.

France, however, suffers from low consumption due to high unemployment. The IMF posits that economic support programs expired too soon. Italy, Greece, Portugal, Ireland, and Spain face more serious problems. They suffer from a significant deficiency in terms of competiveness combined with high public debt. They are constrained to reform markets without affecting private consumption. The most important subject in Europe is the consolidation of the government budgets and long-term ability to service existing public debt. Only countries less affected by the crisis, such as Poland, or countries with strong private and public balance sheets, such as Turkey, can progress relatively unscathed.

Several key issues are similar across industrial nations. The financial crisis would have caused unimaginable consequences for the economy, society, and politics of developed economies had it not been for government stimulus programs and rescue packages. The crisis was the consequence of wrong incentives and global misjudgment. A more dramatic restructuring, such as those in the late 1990s and early 2000s in several emerging markets, could have cleansed the global financial system, but economic, social, and societal risks and costs were unpredictable. Decision makers therefore focused on fighting symptoms to allow the system to recover. Instead of a dramatic and painful one-time restructuring, a path of gradual change was chosen. As the problems arose primarily from debt, the only effective solution is sustained debt reduction. This applies to all market participants, consumers and companies, and public corporations from municipalities to the federal government. Reduction of debt requires that we spend less then we generate in revenue. We therefore must save. Since the revenue bases of the state and corporations depend on continued consumption and investment, it would not be wise to reduce expenditures. To generate the necessary means to reduce debt, incomes or revenues must increase. Ultimately therefore, economic growth is required to afford and balance the fight against the symptoms while steadily improving the financial system.

The difficulty lies in generating solid economic growth without incurring new debt. Growth is generated through domestic demand as well as the export of goods and services. Countries are therefore dependent on domestic demand and demand for exported goods and services.

In addition to the difficulty of generating new income to reduce debt, the management of existing debt is getting more complex since financial markets associate distinctly higher risks with some of the developed nations. As a consequence, credit terms worsen and further reduce freedom of action of governments.

We need to critically review the general competitiveness of industrial nations.

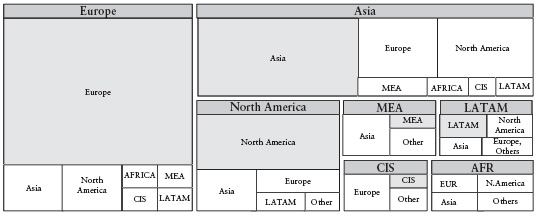

Exports of developed nations have changed significantly during the last decade. Figure 7.2 shows exports by region and destination in 2009.

FIGURE 7.2 Exports and Destinations by region, 2009

Source: International Trade Statistics 2010, WTO, Rising Star research.

It is noticeable that regions such as Europe, North America, and Asia primarily trade among themselves. Latin America, the Middle East, and Africa have more diversified trade partners. What does the high proportion of intraregional trade mean? The obvious conclusion is that regions with important intraregional trade are less dependent on diversified exports. While this may seem an advantage, deeper analyses reveal a double-edged sword. Trade statistics are often used for or against the de-coupling theory. As such, a decoupling trend was argued by some based on the increased intraregional trade in Asia leading to a reduced dependency of Asian economies on developed nations. This seems to stand to reason. However, it remains to be seen whether this is an advantage and whether decreasing trade diversification also reduces risks. In the past 10 years, emerging markets such as the BRICs generated strong economic growth and continued growth is generally expected. It is therefore beneficial for Asian economies, and other fast growing economies, to strengthen intraregional trade.

Less dynamic regions such as the United States and Europe seek to increase trade with dynamic regions such as the BRICs. In fact, developed economies have steadily increased their exports to the BRIC economies. Nevertheless, these exports declined as a proportion of intraregional trade.

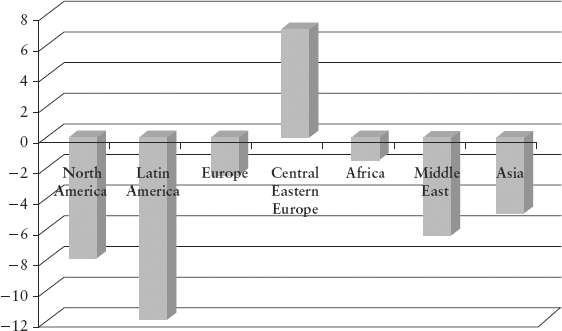

Developed economies are therefore becoming more dependent both on the BRIC markets and domestic and regional consumers. The reduction of trade as a percentage of GDP for Latin America and Asia (Figure 7.3) is a positive development, as it demonstrates the increasing importance of local consumption in driving economic growth. One could argue a regional coupling of dependency. This regional cluster trend is reinforced by rising transportation costs. At a market price of US$100 per barrel for oil, transport cost between the United States and Asia are equivalent to a 10 percent import duty, a considerable hindrance to trade.

FIGURE 7.3 Export Share of GDP in Percent Change, 1999 to 2009

Source: World Trade Organization, International Trade Statistics 2000–2010, WTO, Rising Star research.

Future economic growth of developed nations therefore depends primarily on domestic demand by consumers and corporations. In turn their demand depends on their disposable incomes and outlook. The outlook determines the saving rates and credit demand and thus total capital of an economy for consumption and investment. In the past decade credit demand was high, and between 2000 and 2009 households considerably increased their indebtedness, except in Germany and Japan. In the United States, Canada, the United Kingdom, and Spain private debt in 2009 exceeded 80 percent of GDP. Japan, Germany, France, and Italy household debt for 2009 was between 40 and 70 percent of GDP. The financial crisis increased the uncertainty of consumers. A report by The Boston Consulting Group (BCG) in 2010 concluded that the slower the economic growth and the higher the private indebtedness, the lower the confidence in the future. This seems compelling since existing loans have to be serviced first. Any consumer reticence slows recovery. Although the lessons learned from the financial crisis should instill some financial discipline in households, debt reduction has not yet started and consumers in developed economies only plan to reduce their consumption.

According to BCG, 85 percent of all consumers plan to either maintain or reduce their consumption expenditure while more than 80 percent of consumers seek cost-effective substitution products. This does not augur well for producers of high cost, high quality goods. The contribution of private households to the GDP of developed nations could decline significantly if financial discipline of private households increases along with higher savings and lower cost consumer goods. Employers are the determining factor for private households, as they create employment opportunities and decide salary increases. Yet, the ability of companies in this respect is constrained by low capacity utilization and financial stress.

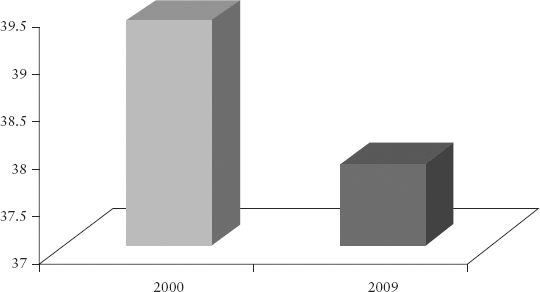

OECD statistics in Figure 7.4 show a decline in average weekly working hours for full time employees between 2000 and 2009.

FIGURE 7.4 Average Weekly Working Hours, Full–Time, 2000 to 2009, in Selected Industrialized Nations

Source: OECD, January 2010, Rising Star research.

Although these numbers hardly predict future employment levels, they suggest a rather sobering employment demand.

The financial situation of corporations is not dissimilar to the situation of private households. The debt burden has increased, except for Japan. Debt of non-financial corporations in all major global economies is particularly high: In the United Kingdom, France, and Spain corporate debt exceeds 100 percent of GDP. Corporations are exploiting low interest rates to reduce their cost of debt capital. Loan requirements by banks are getting stricter so that corporations must adopt more financial discipline to be able to refinance or restructure their debt burden. The objective of increasing liquidity of the financial system in order to motivate banks to increase lending to businesses has failed. Monetary aggregates in the United States show that liquidity stays with the banks. Then again, it may not be wise to address a financial crisis with new borrowing.

During the recession following the financial crisis, government tried to support the most critical sectors of the economy. The idea was to gain time until consumption regains its strength. How purposeful such policy is and whether government can afford such a policy remains an important yet unanswered question. First, current government action has dramatically increased public debt. The result has been historically unprecedented rescue programs to prevent the collapse of public finances in weaker Euro economies. Interest tends to rise to compensate capital providers for the increased risk interest rates have. Yet interest rates remain at very low levels. There are more market asymmetries.

Risk premiums for public debt of some developed nations are at the same level as those for some emerging economies that have significantly lower credit ratings. Factors outside pure default probabilities seem to determine the pricing, but ultimately only the trade-off between interest payments and default risk matters. The market typically corrects the current asymmetry, which should lead to either a revaluation of the creditworthiness of emerging markets or a devaluation of the creditworthiness of certain developed economies. The latter would lead to increased interest payments and a substantial burden on government budgets. As a consequence, any increase in interest rates is fiercely resisted in Europe. Proposals by the Euro Group to issue Euro-wide Union bonds to include all member states with collective liability would reduce the interest cost for the weakest economies at the expense of the strongest economies such as Germany.

The ability of government to remedy the symptoms of the crisis and return to business as usual is limited. The effectiveness of public economic stimulus packages on the GDP has been increasingly the subject of academic studies.3 Harvard professors Barrow and Redlick suggest that the multiplicator of public consumption on the GDP trends toward 1 only in an environment of high unemployment but remains between 0 and 1 otherwise. This contradicts the statement of the Obama administration, which claims a multiplicator of 1.5 for its measures. Results by US economist Ramey are similar: The multiplicator of public expenditure ranges between 0.6 and 1.1 times GDP. The reason for the limited impact of public consumption lies in the decision making. Government consumption is an inefficient political decision process and not based on actual market demand.

The capital deployed by government for its stimulus packages reduces the capital available to households and corporations. While stimulus packages are an expensive luxury, they compensate for significantly lower household and corporate consumption due to prevailing uncertainties. This strongly cyclical behavior reinforces economic cycles and may lead to excessive stock exchange movements. The true cost of public measures is already felt both in the United States and Europe. Governments need to reduce expenditures; a fiscal crisis is on the horizon. Public consumption must be reduced and refinanced through tax increases. Both have negative effects on economic growth.

Thus, since the financial crisis, economic growth of industrial nations depends increasingly on the success of emerging markets that determine global economic growth.

Globalization stands for all efforts that contribute to the free flow of goods, capital, and other production factors across the globe. Initial advocates of globalization, multinationals and multilaterals from advanced economies, praised the advantages of better access to production means and reduction of market entry barriers in emerging economies. Others argued globalization as a means of poverty reduction. While there has been limited success in poverty reduction during the first decade of globalization, several emerging markets faced severe financial crises in the 1990s due to errors in opening their markets.4 The tide has turned and following the last financial crisis, developing economies emerged stronger than industrial nations from their crises and the lessons learned.

More and more goods and natural resources originate from countries that were asked to lower market access barriers for our goods. The resulting growth dynamic creates technology competencies that compete with those of developed nations. The idea of China as “extended production facility” has long been applicable to other emerging economies that are less advanced. Global trade flows thus are increasingly from emerging economies toward industrialized economies.

Globalization increases competitive rivalry. Where do industrialized nations stand? Growth of industrial nations depends on their competitiveness not only with their exports but also in their domestic consumption. After all, consumers will choose imported goods for better prices or even for higher quality.

The competiveness of a nation depends on several factors: In principle, these are the availability of production factors, the competency of the domestic industries, and strength of domestic consumer demand. The latter reduces dependency on foreign trade. Equally, administrative barriers and taxation affect competiveness. These factors have changed considerably over the past 10 years and we shall review the current state of affairs.

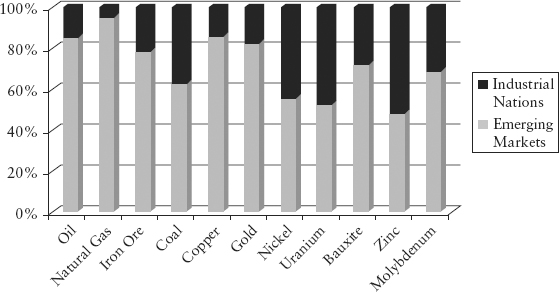

Recent experience in the Western high-tech industry related to China’s export restrictions for rare minerals as well as the scarcity of qualified professionals in Germany demonstrates the importance of production factors for economic growth. Emerging markets cover 73 percent of global land and about 81 percent of global population. This suggests that emerging markets also cover the majority of global natural resources and global working population. In fact, reserves of natural resources in emerging markets significantly exceed those of industrial nations (see Figure 7.5). The value of these resources, on which the growth of emerging markets depends heavily, has also increased dramatically.

FIGURE 7.5 Distribution of Global Natural Resources

Source: Fidelity International, Rising Star research.

About 1.2 percent of the population in China owns a car, while in Germany ownership is 50 percent. It is not hard to imagine the long-term consequences of vehicle registration in China with respect to the demand for gasoline once China catches up to developed economy standards. Demand for natural resources will further increase and consequently their prices. This will lead to distribution effects between industrial nations and emerging markets and between emerging markets themselves. The distribution effect between emerging market themselves is difficult to estimate. However, the collective competitive advantage of emerging markets with respect to natural resources is evident. The consequential dependence of industrial nations is evident well beyond the oil crisis of 1973.

Table 7.1 shows the value index of different natural resources that underscore the growing advantages of emerging markets.

TABLE 7.1 Natural Resources Price Changes, 2000–2010

Source: Rogers International Commodity Sub-Index Total Return, Rising Star AG research.

| Agriculture | +46.02% |

| Metals | +379.77% |

| Energy | +106.95% |

Scarcity and the strategic necessity of natural resources has led to multiple, often armed, conflicts. It is interesting to note how China is securing global access to natural resources without conflict. Developing mutually beneficial relationships is a specialty of China’s natural resource policy. Expensive armed conflicts have been avoided while their political influence has grown. The shift in political power toward emerging markets will be discussed later.

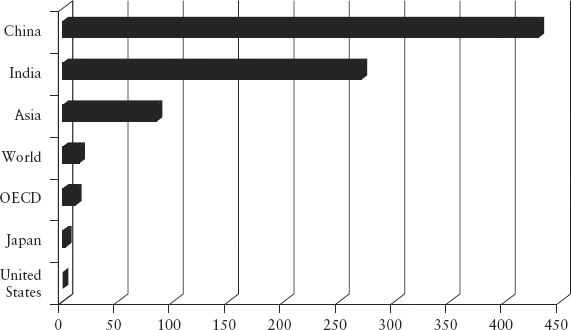

In the past, high-technology nations such as Japan and Germany with few natural resources were able to compensate for their disadvantage through a qualified workforce and high performance in research and development. Product complexity and production processes require specialized skills. In particular, Asian emerging markets were not considered a threat in the 1990s due to the perceived gap in specialized skills. Since then, Western multinationals have exported specialized skills to China. One of the key virtues of the Chinese leadership was to combine market entrance and profit opportunity of Western companies with a transfer of skills. At the same time, the education system expanded greatly. Today China alone generates more university graduates than all major industrial nations combined. Critics claim that only half of these are actually well educated, but even half would be a significant factor. China, Brazil, and Russia together graduate 10 million students each year. The most important industrial nations combined achieved about 4 million graduates. This is less than half and it is only a question of time until universities in emerging markets provide the same quality of education that industrial nations provide. The reduction of education budgets of industrial nations caused by the present fiscal crisis will further compound this discrepancy.

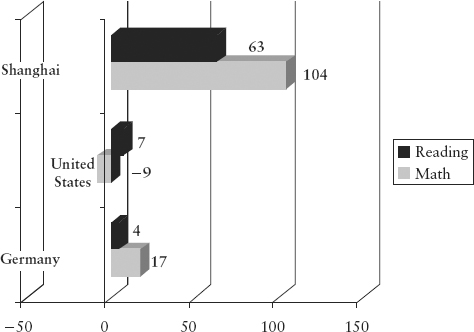

China is the pioneer in education among emerging markets, at least by measurable standards. The OECD Pisa 2009 study demonstrates China’s lead, although only Shanghai was included, as shown in Figure 7.6.

FIGURE 7.6 Pisa Results Relative to OECD Average Scores

Source: OECD Pisa 2009, Rising Star research.

Even more indicative are patent registration by various nations at the World Intellectual Property Organization (WIPO). Patent registrations are somewhat indicative of usable research output. Notably China ranked third in number of patent applications for each of the years 2006–2009 and the high growth rate of China’s patent registration is indicative of a growing innovation capability. Russia and India still have some way to go. Looking at patent registration dynamically, major industrial nations such as Germany, the United States, and the United Kingdom, show a declining rate of registration while China is quite the opposite. The catch up with respect to human capital is in full swing. Since patent registrations are the outcome of several years of research these numbers reflect the educational progress of several years. This trend could strengthen over coming years.

Already today we note that, for example, German imports of research and development services has strongly increased. A prominent example is the recent decoding of the genomes of the EHEC virus by Chinese researchers at the Beijing Genomics Institute, one of the leading institutes. They have the most advanced equipment and technologies, so the genomes could be decoded in three days. In Europe and with older equipment, this would have taken up to two weeks.

Research and development imports from China increased more than fourfold over the period 2004 to 2008 and equivalent imports from India more than threefold (see Figure 7.7). In addition, China exports more research and development services to the European Union than the European Union exports to China. These numbers demonstrate that the production factor human capital has dramatically improved in emerging economy.

FIGURE 7.7 German Imports of R&D Services in Percent Change, 2004 to 2008

Source: DB Research, Eurostats, Rising Star research.

In the same way, productivity of the workforce improved rapidly in emerging markets. While work productivity in Europe increased by 1 percent yearly between 2000 and 2008, work productivity in Brazil, China, and India rose on average by 7.7 percent a year. Also in Africa where productivity is steadily rising, work productivity increased by 2.8 percent per annum over the same period. This increase in productivity somewhat mitigates the effects of labor cost increases and thus contributes to the attractiveness of human capital in emerging economies. Human capital compounds the competitive advantage of emerging economies over established industrial nations.

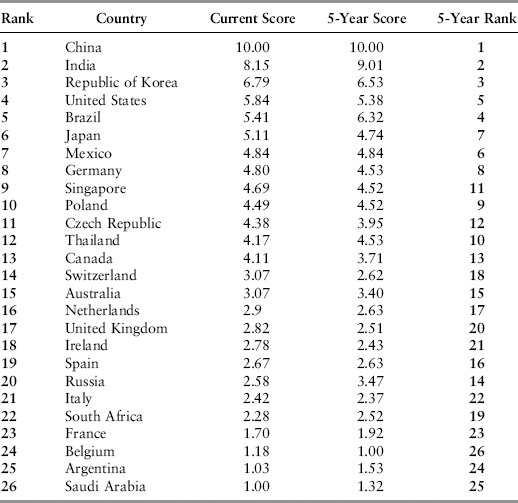

Industrial nations have lost their leadership in the area of manufacturing competiveness, as evidenced by the Deloitte Index of Global Competiveness in Manufacturing (Table 7.2).

TABLE 7.2 Manufacturing Competitiveness—Current and 5 Years Out

Source: Deloitte and US Council on Competitiveness, 2010 Global Manufacturing Competitiveness Index, Deloitte Touche Tohmatsu, 2010.

Strong domestic consumption strengthens economies and provides resilience against weak export performance. Local consumption of industrial nations suffers increasingly from demographic trends—the birth rate of industrial nations is on average 1.7 children per couple, as opposed to 3.3 children in emerging markets. The consumer basis of industrial nations tends to decrease long term. Projected annual population growth rates in Europe and the United States for the coming five years are 0.03 percent to 0.9 percent. After 2015, Europe will start to shrink. At the same time, projected real GDP growth rates for industrial nations until 2015 are 2 to 3 percent per annum. Per capita growth of real GDP is weak. Any private debt reduction or moderate tax increase will thus noticeably reduce future private domestic consumption.

Equally relevant for the assessment of consumption development is the expected change in income structure. Couples with tertiary education have fewer children and have them later in life. Thus the main population growth happens in segments with lower education. Academic studies demonstrate that the life income of children heavily depends on levels of education and net worth of their parents. This suggests a further concentration of net worth and income within the population. Employment with low qualifications will tend to migrate abroad, much as in the past the automotive supplier industry migrated to Eastern Europe. Already today the proportion of under-skilled labor seeking employment for more than six months exceeds 60 percent.

Emerging markets increasingly diversify their economic and industrial structure. This increases their relative advantage over developed economies and attracts low qualification employment. We can therefore also expect a reduction of income and net worth in lower income segments of developed economies. Although this part of society consumes little, they reduce the consumption potential of other households through the social transfer payments they receive. Social payments today already amount to 32 percent of the German federal budget. The proportion of social payments will increase because the balance of social transfer receivers or payees to employees or payors increases. This increases public financing requirements.

Since we require a qualified labor force, we hire increasingly from emerging economies. After a few years, these imported laborers then return as specialists to their home countries. The foreseeable democratic development is therefore not conducive to the growth of domestic consumption. Although not all economies have a similarly wide social system as Germany (covering essentially the entire population and multiple conditions of individuals, e.g. unemployment, disability, family care, etc.), the structural demographic issue is widespread. Not only are baby boomers in the United States reaching retirement age, they saved little and consumed much. As soon as income drops, consumption will decline considerably. We can therefore expect negative domestic growth in consumption.

This is particularly important for the United States, as its economy depends to almost 80 percent on domestic consumption. Such dependency was sometimes an advantage in comparison to economies like Germany’s that are more exposed to global economy developments. In 2007, the average indebtedness of US households already stood at 138 percent of income. Since 2000, private consumption has been on average 77.3 percent of GDP. If, therefore, domestic consumption declines by 1 percent, GDP growth declines by 0.77 percent. Clearly, this also depends on the development of disposable household income, but the impact of reducing consumer debt as opposed to consuming is evident particularly in light of the increase in consumer debt in the past decade by more than 30 percent above its long-term trend (see Figure 7.8).

FIGURE 7.8 US Private Debt in Multiple of Income

Source: Federal Reserve, McKinsey Global Institute analyses, Rising Star research.

The way back could be tough for a consumer dependent economy such as the United States. The continuously declining savings rate over the past 30 years contributed actively to economic growth. Therefore, continued growth in consumer credit is critical. A capital restructuring of companies, households, and the federal government could rapidly result in several years of depression.

The financial crisis was more than a wake-up call. It went to the heart of financing growth of industrial nations. Consumers, companies, and the government got into the habit of living beyond their means at the expense of the future. The foundation of our economy is becoming increasingly fragile while the time span between consumption enjoyment and future falling off the cliff is getting close to zero. Through measures that either provide liquidity or open rescue parachutes, we were able to extend the time frame. Experience suggests that the distance between renewed alarm signals and conceding defeat is shortening until it turns hectic again and we regret not having acted earlier. Many of us face this dilemma in our daily lives. A transfer of this experience to high-level decisions only happens rarely. Several countries and economies are now under severe pressure and must assess under pressure desirable and necessary measures and the real availability of freedom of action.

Public debt of the G7 economies has reached proportions not seen since the end of World War II. It was not the crisis itself but our behavior over several decades prior that led us to this situation. Growth weaknesses have been compensated for by new public debt while in phases of high growth public debt was not reduced. We now need a serious change of tack to stabilize the fiscal position of economies and prevent further deterioration. The continued aging of the population will increase the cost of health care and retirement. To reduce public debt we must therefore first absorb cost increases. This represents a definitive challenge. Current growth in Germany is fragile, as it primarily based on exports. Few resources are left for countercyclical measures. Several countries are experiencing financial difficulties that also increase interest costs for other nations.

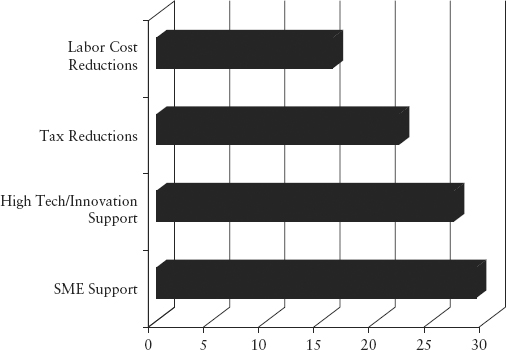

To avoid a fiscal crisis, governments need to increase their incomes and reduce their costs by both restricting private households and corporations. However, according to a study by Ernst & Young (see Figure 7.9), industry decision makers are asking for more stimulus measures to improve economic growth prospects.

FIGURE 7.9 Top Four Measures to Stimulate the European Economy in Percent

Source: Ernst & Young, 2010 European Attractiveness Survey, Rising Star research.

Most of the measures primarily asked for will increase government expenditure. Yet none of the highly indebted European countries can really afford such growth stimulus since countries either require surplus budgets or high economic growth to keep indebtedness in check. It is assumed that the most highly indebted countries will depend on strict fiscal discipline until 2020. Strict fiscal discipline is a barrier to stimulus measures. This recurring dilemma has cost many central banks their independence from politics. As long as interest rates are low, the government can refinance its debt. The required fiscal discipline is the difference between cost of interest and cost of growth. In times of low interest, less economic growth is required; respectively, with some economic growth less fiscal discipline is required. This explains the inherent interest of governments in keeping interest low.

If interest does not compensate the market adequately for the risk taken, sovereign spreads, the insurance costs for government securities such as credit default swaps, increase. Looking at default insurance for five-year government securities over the past 16 months, very significant differences are evident. Interest should therefore be much higher to eliminate the need for insurance. To avoid an unrealistic deleveraging at the moment, monetary aggregates are expanding. However, experience suggests that expansive monetary policy leads to a rise in interest rates to combat inherent inflationary pressures. To date inflation is under control but interest should adjust to the risk incurred while controlling inflation due to expansive monetary policy. As long as this does not happen, we have a market asymmetry that reduces the value of the currency. If interest rates subsequently increase, a devaluation of the currency is expected. This affects primarily the currencies of industrial nations, especially the US dollar and the euro.

Central banks and governments of highly indebted industrial nations then are challenged to implement a mix of fiscal discipline, increase public income, and expend stimulus for the economy. Any two of these goals can be achieved, but all three together are vastly more complex. The rebalancing of public budgets will also require corporations and households to scale back growth, with negative consequences for government finances.

For some time it has been recognized that the voting structure of multilateral organizations such as the IMF or the G8 does not properly reflect the global economic power structure. Until recently, large economies such as China and India only had a spectator role; smaller economies in Asia and Africa often no role at all. More recently, there has been a call for giving emerging markets a wider role in multilateral organizations to better reflect realities of global markets.

The G20 meeting in January 2008 made a start in recognizing economic realities. Since then the IMF has reformed voting arrangements to give emerging economies a higher weight. Since 2009, emerging economies are also members of the Financial Stability Forum. Also, the voting rights of countries such as China have been dramatically increased since 2010. In the meantime, China has the third largest number of votes at the World Bank. Emerging economies play a critical role not only with respect to capital markets; it is hard to imagine any meaningful dialogue or result in meetings on climate change or environmental protection without the participation of China, India, and Brazil.

This change in the architecture of global power emphasizes the shift toward emerging economies. Key emerging economies are rightly more prominent, based on their fundamental role.

Minor emerging economies still have a long way to go before their voices are heard. There are, however, encouraging signs. In April 2009, the then British Prime Minister Gordon Brown invited several government representatives from Africa and Asia as observers. Even though they were not allowed to participate directly, this represented a major improvement over those meetings where they were not even present.

The reason to give poorer emerging markets a more prominent voice in multilateral organizations is both humanitarian and economic. Thus a variant of G30 has been proposed. Proponents argued that the world is simply too small to exacerbate the division into rich and poor. The credibility of multilateral organizations is also at stake: As long as organizations such as the Security Council of the United Nations do not represent India or Africa, they can hardly be considered democratic forums.

The greatest challenges of globalization, such as climate change, nuclear technologies and weapons, natural resources and energy security, poverty, and social inequality, require the collaboration of all international actors. To progress in these areas for the years to come, emerging economies need to fortify their position in global multilateral organizations.

Until now, the global political arena was dominated by economic Darwinism and capital power. Every step now means a shift in balance. This will positively affect societal and economic developments in emerging markets. A stronger representation of emerging economies is welcome because the global economy gains stability. The redistribution of economic power and capital has been ongoing for decades. This is particularly evident by the country of origin of the wealthiest 100 individuals. In 2000, 90 percent of the wealthiest individuals came from industrialized nations. Only 10 years later, their share was only 64 percent. More than a third of the wealthiest individuals originate from emerging economies. This roughly represents the share of emerging economies in global GDP.

The substantial change in power structures under way will require time to fully materialize but it is clear in which direction it will unfold. In 2020, the share of emerging economies in global GDP will be around 50 percent and that could merely be a stopover. Implications for global power and voting redistribution are far-reaching and we may well witness a new world order in which emerging economies will rise to become equal partners at the level of industrial nations.

While professional historians prefer to see the past as unique events and distance themselves from commenting on patterns in the past, Professor Paul Kennedy, Yale University, took on the challenge of describing patterns in the past that are relevant today, in particular to be considered by political decision makers. In his book The Rise and Fall of the Great Powers, he postulates a thesis on why nations rise and fall and provides as evidence a rather undisputed history of Europe and the great powers between 1500 and 2000 and the subsequent confrontation of superpowers.

The principle of his thesis states that the more power a nation acquires, the higher the public expenditure to maintain such power. The ability to maintain a conflict with a nation of similar size or a coalition of nations is inseparably linked to economic performance. At the peak of their military power, most states are already in an economic decline. The United States is no exception to this rule. Power can only be secured through a fine balance between economic net worth and military expenditure. In the process of decline, nations invariably shift their emphasis from economic performance to military expenditure. Spain, the Netherlands, France, and Great Britain did exactly that. After the Soviet Union, the United States may be on the same path.

The pattern of excessive expansion and decline is clearly visible in Spain in the sixteenth century. To maintain power, a combination of excessive public debt and inflation would have brought the country to its knees if not for its main rival, France, being in even worse condition. But by the seventeenth century, France introduced a new system of bureaucracy and military administration that brought its considerable economic resources to bear. Only a combination of all other European powers was able to avoid the dominance of France over the continent. France itself then expanded beyond its means and was soon unable to sustain the costs of its military participation, which led to insolvency and fueled the French Revolution.

France’s main opponent was Great Britain, whose claim to power was economically based rather than military. During the eighteenth century, a virtuous circle was created: The network of trade partners generated funding and loans that were necessary to finance the navy to protect shipments, further expand the trade network, and impede competing trade. At the same time, Great Britain was able to raise the capital necessary to fund technological progress that ensured its leadership for a good part of the nineteenth century. Toward the end of the nineteenth century, Great Britain needed to devote increasing resources to its navy; after various extended war operations, only a massive increase in private and public debt and the liquidation of profitable overseas assets prevented a collapse of public finance. In the early twentieth century it required the support of the United States to allow the Allied troops to successfully end World War I. Thereafter, Great Britain declined steadily since it was unable to sustain the levels of expenditure necessary to maintain control and defense of its vast overseas empire.

The German Empire was doomed by its leaders and political structure, although Germany dominated the continent economically and politically toward the end of the nineteenth century. Waging two disastrous wars in the twentieth century in which a hopeless confrontation with the United States and later with the Soviet Union was initiated, Germany was unable to translate its economic performance into political leadership.

The United States emerged as the global leader from the two wars and its economy was greatly stimulated by them, although like other nations in the past, the United States benefited from little competition for leadership. During its global leadership, the United States took on very significant commitments. Since the recovery of Europe and Japan and the rise of emerging economies such as China, Brazil, India, and Russia, the United States is gradually moving toward being primus inter pares, or first among equals. Like other nations, the United States failed to create a domestic taxation system that would generate the huge resources required to fund military developments. Instead it turned to foreign markets. This is only sustainable because other superpowers are not in a much better position.

Dr. Kennedy’s postulations are more than 25 years old, but nothing much has changed in the overall context of global developments. It cannot be contested that we live in a multipolar world under the political leadership of the United States. It remains to be seen whether today’s leaders are doomed for decline or if the world can engineer a system or power oligopoly.

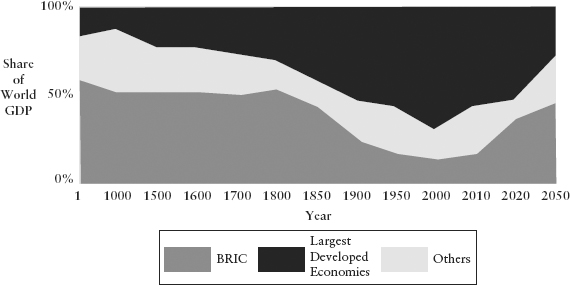

Economic growth in emerging markets and resulting opportunities for investors are a long-term and core investment subject, and not only since the financial crisis, since for more than 30 years now emerging markets have consistently achieved a higher share of global GDP than developed economies (see Figure 7.10).

FIGURE 7.10 Share of World GDP—Year 1 (AD)—2050

Source: IWF 2001, Goldman Sachs GE CSR 4, 2009, Angus Maddison, Rising Star research.

What has changed is the approach by investors and the available choices of attractive investment opportunities. High growth rates of emerging economies have proliferated. While 30 years ago the emphasis was on Asia and Tiger economies, today a broadly diversified set of dynamically growing economies exists with different structures and at different stages of development. Globalization has reduced barriers to trade and led to the liberalization of markets. This new freedom challenges the governments and management of companies of emerging markets and leads to many errors in judgment, culminating in the emerging market crisis at the end of the 1990s.

The knowledge gained from this experience is evidenced by the resilience of emerging economies during the financial crisis. As risks in emerging markets are decreasing, investments in emerging markets are no longer speculative. Rather they migrated from a specialty to a mainstream counterweight to industrial nation investments. The role of emerging markets in the portfolio of professional investors is nothing but a mirror image of the role of emerging markets as growth leaders of the world economy. For the investor it is critical to understand the driving framework conditions of emerging markets and how permanent these developments are.

The basis for long-term growth in emerging markets is multifaceted. This has advantages and disadvantages for the decision process of investors in emerging economies. This complexity should be seen as a positive aspect but it requires skills to fully master the subject. The reward of such preoccupation is the recognition that growth and development of emerging markets is a forgone conclusion and solidly grounded in the variety of observable fundamentals.

The base for the rise of emerging markets is the liberalization of trade and financial markets as well as the creation of functioning legal systems to secure property rights. Although freedom of goods and capital flows has not been completed yet, great progress is being achieved. Some reticence can be explained by the painful experience at the end of 1990s. During that period, capital markets were opened fairly rapidly at the instigation of industrialized nations without being fully prepared for the ensuing responsibility and national interests. Mistakes were made that are partly attributable to the pressure of industrial nations. Resulting crises are forgotten but the knowledge gained allowed emerging economies to remain largely unscathed by the recent financial crisis.

Emerging markets today prefer a model that fits their specific needs and allows for gradual adaptation rather than following the model of industrialized nations. This is very positive for investors, as risks are better mitigated. In the course of this liberalization a number of regional trade agreements and treaties were concluded that allow a frictionless exchange of goods and capital within a region in adaptation of the model of the European Union Customs Union. Equally in this arena, the reduction of tariffs and duties is gradual to allow for domestic adjustment. Reduction of bureaucracy in trade increases trade velocity and increases intraregional trade profits. The potential of AFTA, for example, is by no means fully exploited since many measures are planned but not implemented. They include standardizations in documentation and reduction of tariffs, infrastructure improvements, and even very long-term plans such as a common currency along the lines of the euro.

Emerging markets will not repeat the mistakes made by model industrial nations. In this respect, the European Union plays a pioneer function that demonstrates much room for improvement. Equally outside AFTA, developments are under way. The regional economies of Africa and Latin America have objectives similar to those of AFTA. Each planned simplification of trade will increase trade profits and increase the efficiency of regional markets. The governments of emerging markets are successfully working on increasing market efficiency by targeting a reduction of red tape and reforming the legal systems.

China demonstrates beyond doubt that democracy is not a requirement for economic success. Many of the political decisions faced by emerging markets to be competitive in the global landscape extend over several election periods so that continuity and independence from the next election may be an advantage.

The Harvard economist Dani Rodrik postulated the Impossibility Theorem in connection with globalization.5 The theorem argues that of the three desirable goals—globally integrated economy, national sovereignty, and democratic legitimization—only two of these goals can be accomplished at any one point in time. In Europe we have come to realize that in the course of the euro crisis, we have to accept some loss of national sovereignty in order not to make concessions on matters of democratic legitimation and integration of the European economies. The leadership of China does not claim democratic legitimation and can therefore achieve the goals of globally integrated economy and national sovereignty. Although not uncontested, the political system of China seems to give the country a competitive advantage that fosters economic growth. By contrast in Europe, rather right-wing parties are getting stronger, probably in support of the national sovereignty agenda.

In general, emerging markets have healthier budgets and higher reserves than industrial nations. As a consequence they enjoy wider freedom of action to engender economic growth. At present, growth is excessive and stimulus programs are being curtailed all around. It was during the financial crisis that emerging economies for the first time were able to institute countercyclical measures. Given the success of these measures, emerging economies can now reduce growth investments and amortize the cost of their stimulus measures. If emerging economies succeed in amortizing their stimulus packages, they will be a good step ahead of industrialized nations. Industrial nations never recovered the investment or reduced the debt caused by countercyclical measures in subsequent high growth phases.

Industrial production of emerging economies has not only recovered to pre-crisis levels but regained a position exactly on the long-term trend and well ahead of industrial nations that are still 15 percent below their long-term trend and even below pre-crisis levels. Stimulus packages in emerging economies can therefore be reduced without endangering growth, and thus avoid any overheating of the economy. This situation seems unjust from the perspective of industrial nations because emerging markets can amply afford stimulus packages but do not require them anymore. Industrial nations require further stimulus packages but cannot afford them. The diverging trend of growth paths will therefore continue and it is less surprising that emerging economies increasingly step into the strong role of creditors. Liabilities of industrialized nations to emerging markets are increasing. This opens new avenues of influence and market development. News of emerging markets companies buying competitors in North America or Europe are plentiful as is news of financial aid packages for stressed euro countries. This would have been unthinkable only a short time ago.

The overwhelming difference in financial strength between industrialized economies and emerging markets is demonstrated by their respective reserves. Since about five years ago, emerging markets have been holding the majority of currency reserves, today about 65 percent. The distribution is exactly the opposite of the distribution in GDP. In proportion to their GDP, emerging markets have more than three times the fire power for growth stimulus, fiscal expansion, and currency support measures.

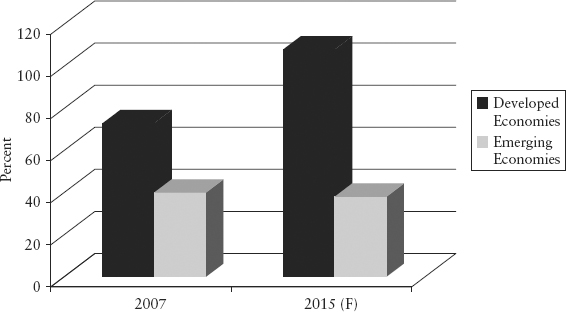

Moreover, levels of public debt are comparatively low for emerging markets (see Figure 7.11). Very few of the emerging economies would have a problem meeting the Maastricht debt limitations. In fact, those who used their reserves most are among the euro countries. Even in 2010, still during the phase of stimulus measures, growth in new public debt of emerging markets was −2.8 percent.6 On average, 80 percent of all emerging market debt is held by nationals. Another advantage of emerging markets is the relatively low rate of taxation and the relatively low base of taxpayers. There is therefore room for significant revenue improvement. Since social transfers are much lower than for industrial nations, governments face less financial pressure. This is caused on the one side by demographic developments but equally by easier access to finance by emerging economies driven by higher ratings and the reduction in interest burden.

FIGURE 7.11 Public Debt as Percent of GDP—Pre-crisis (2007) and Projected (2015)

Source: IMF WEO update 2010, Rising Star research.

Some countries such as Brazil, Costa Rica, Peru, Panama, or Morocco experienced a ratings upgrade to investment grade in the midst of the financial crisis. Since the crisis, there have been six ratings upgrades for every one ratings downgrade of emerging economies.

As outlined earlier, emerging markets hold the majority of global production factors, be they capital, human resources, or natural resources. China, by far the largest emerging market, requires large quantities of natural resources both for domestic use and for export production to the great benefit of Africa and Latin America. These regions, except, for example, Brazil, are not as far advanced in manufacturing as some Asian and Eastern European economies. Natural resources constitute a form of monopoly for those economies that are endowed with the resources. Capital is mobile and will migrate to attractive investment locations. Human capital requires longer gestation periods. In this respect the increased education expenses of emerging economies in the past 5 to 10 years will prove an advantage over the coming 10 to 20 years. Overall, emerging markets possess all production factors necessary for their own growth. Accordingly, trade relationships of the future will tend to improve to the benefit of emerging markets.

The population of emerging markets is very young. The median age of emerging markets is 28.1 years while the median age of industrialized nations is 39.9 years. A comparison of the population age structure between industrialized nations and key emerging markets (China, India, and Brazil) reveals one major difference: The population of emerging markets decreases with increasing age groups; they form a true pyramid, while in industrialized nations the population of age groups above and below the median decreases. This means that in emerging markets those in retirement are compensated by a sufficient number of economically active individuals. Retirement systems of emerging markets, insofar as they exist, are faced with considerably less pressure than those of industrialized nations. For the latter, the numeric relationship between pensioners and economically active individuals is getting worse as the baby boomer generation is nearing retirement age. Social transfers will therefore certainly increase for industrialized nations and further reduce disposable income.

At the same time, this demographic trend reduces the previous quasi monopoly of industrialized nations with respect to human capital. Regardless of the quality of education, industrial nations will have a smaller qualified work force in absolute numbers. Mobile employment seekers from emerging economies will benefit from this gap in human resources. They may have the opportunity to gain experience in industrialized nations and transfer acquired competencies to their home countries. The competitive position of industrialized nations is therefore hardly sustainable at the current level.

The consumers in emerging markets will not have to worry for some time to come about high social transfer payments. Governments of emerging markets have recognized that they have to invest in education to provide a growing part of the population access to the emerging middle class. From their perspective, it seems the best way to counteract inflation caused by a lack of qualified workforce and potential social unrest due to the inequality of income distribution. The young generation receives a better education than their parents did and can aspire to higher incomes. Local consumption is therefore set to rise. This trend is augmented by increasing urbanization. The transformation of economies toward services and manufacturing creates employment in agglomerations and cities. These agglomerations create efficient markets for employment, goods, and services. In aggregate, the middle class of emerging economies (annual income of US$3,000 to $30,000) will double within six years and count almost 1 billion individuals by 2022 (see Figure 7.12).

FIGURE 7.12 Aggregate Middle Class—China, India, and Brazil (in millions), 2010 to 2022

Source: Goldman Sachs Global Economics, Commodities and Strategy Research, BRICs monthly, March 2010, Rising Star research.

This group is equivalent to several billions of US dollars in consumer demand and will make the emerging markets middle class by far the largest consumer group. The middle class of emerging markets alone will be larger than the population of all industrialized nations combined. The equivalent developments in industrialized nations are rather static and, due to the small number, of little relevance. Once a growing number of individuals enters the middle class, the average per capita GDP rises. This promulgates such countries into the middle income class of economies. The income distribution on a global scale is getting more equitable. The number of middle income economies will double in the coming decades. The expansion of the middle class flattens the Lorenz curve, the income distribution within an economy. Already today, India has a smaller Gini coefficient than the United States (CIA World Fact Book, 2011). Increasing demand for all kinds of goods increases demand for natural resources. This will foster the rise of emerging markets that hold most of the world’s natural resources.

Globalization and the consequent rise of emerging economies are often considered a gigantic redistribution process. This is not necessarily wrong, but polarized. Over centuries, pressure from the North-South asymmetry increased. Through liberalization of goods and capital flows, the pressure is being rebalanced. This adjustment process will continue until a balance is restored. It is the nature of this process that emerging markets will benefit primarily from these developments while industrialized nations should urgently rethink and adjust their business models. There is the danger of a gradual loss of economic and political influence with consequential income loss and social changes.

As we know, China toppled the United States as the largest manufacturer in 2010, a position the United States had held since 1895. The reclaiming of the top spot closes a 500-year circle, according to historian Paul Allen. Even this event is only a stopover. Nicolas Craft, long-term economic trend expert from the University of Warwick, considers the change so fundamental that it will not change again in the foreseeable future. The rise of emerging markets, here the example of China, has historic dimensions far beyond several multiyear economic cycles.

We need to ask ourselves which forces govern this redistribution process that is changing our customary economic and political landscape. Assuming that there is no superior order for global distribution equality and that no predestined global economic structure exists, change must be driven by past decisions and resulting dynamics over several decades. We will review individual changes that make up in sum recent economic history.

Following the Stolper-Samuelson theorem on trade, under a framework of increased international trade, production factors of one country are in higher demand and achieve better prices if they are plentiful in comparison to those of other countries. For a leading industrialized nation such as Germany, these factors would be capital and a quality work force. The only production factor that industrialized nations have in excess, when compared to emerging economies, is knowledge. In the past, emerging markets only had excess low cost labor and natural resources. Natural resources probably even generated monopoly gains for the exporting economy. The fundamental dynamic of producing low cost goods with low cost labor in emerging markets started increased demand for low cost goods from Asian manufacturers and was probably at the origin of the prevailing dynamic. Through manufacturing plants investment was attracted. Over time, the economy started to diversify and education improved. As a consequence, these regions were able to attract international companies that reinforced transfer benefits. Good examples from the past are the Asian Tiger economies that started with low cost manufacturing and now sport some of the leading high-tech corporations. Of course, employment for low cost goods migrated to other economies.

A similar development can be observed globally with emerging markets, albeit with regional specialties. China took over the low cost status from Taiwan and is developing further. To date, the quality of Chinese goods has reached a relatively high level according to a study by the ECB and improves continuously (Pula & Santabarbara, 2011). This undermines the current advantage of industrialized nations and fosters employment in rural parts of China and in other emerging markets in Africa, Asia, and Latin America. Countries like Vietnam and Cambodia are already considered extended production facilities of China since labor costs are lower than they are in China. China itself invests heavily in education to avoid any shortage of qualified workers. This policy is not only based on farsightedness; investment in education is part of a long-term plan to fight inflation because continued education and a larger workforce can mitigate demand side pressure on labor cost. The availability of a qualified workforce causes a further diversification of the economy and promotes research and development. Increasingly complex products can be made in China. Already today, China increasingly attracts capital and know-how from industrialized nations. Thus China creates for itself the opportunity to extract monopolistic profits from human capital. The next and the following generation of Chinese will be far better educated. Education investments have long amortization periods but are an essential requirement for economic progress. Germany already imports R&D services from China, a potential alarm signal.

Increase in qualifications and further diversification of the economic structure in advanced emerging economies creates new competitive advantages. Competitive positions are continuously changing. The Stolper-Samuelson theorem also stipulates that for relatively scarce factors such as low cost labor in Germany, conditions worsen with increasing trade. The theory offers an explanation of the fact that in the past one and a half decades about 3 million jobs with social security were lost in Germany while at the same time long-term unemployed have a comparatively low level of qualification. These jobs are now in emerging economies from which we import our products. Competition over the advantages of qualified labor is in full swing. The effect of Chinese imports on the employment situation has also occupied academia. In a recent US economic report, the term China Syndrome was coined. It describes the displacement of low income labor domestically and the consequential cost through social payment transfers from the disadvantaged domestic work force. It is assumed that the negative effects of social transfer payments at least compensate for the advantages of lower cost consumption.

Since transport costs tend to increase, regional trade is on the rise. If a product from Europe is always 10 to 20 percent more expensive than one from a neighboring country, imports from the neighboring country will be preferred. Since over time increasingly more complex products are manufactured by a better qualified work force in emerging economies, the advantages based on knowledge by industrialized economies is decreasing. The availability of goods in regional trade areas such as Latin America, Africa, and Asia is growing. To save transport costs and to support other regional economies for strategic reasons, products from industrialized nations will gradually lose market share. This means that industrialized nations will find it increasingly difficult to participate in the growth of emerging economies through exports. Either industrialized nations develop new business models based on knowledge or the progress of emerging economies will contribute less and less to the growth of industrialized nations. That is the new form of decoupling. Growth in emerging markets is already decoupled from industrialized nations.

In all emerging economies the middle class is growing rapidly. Domestic consumption is already solid in several markets and will increase over the coming years. In China alone, according to Société Générale, the French bank, the middle class will grow by 200 million individuals by 2015. The question that remains is how much industrialized nations can benefit from the rise of emerging economies. If growth of industrialized nations gets separated from the material growth dynamic of emerging economies, countries such as Germany would suffer. In 2010, China replaced the United States as the primary non-European export destination of Germany. Without exports to emerging economies, Germany would be in worse economic shape, similar to other European economies. As a preventive measure, industry is fostering production facilities in emerging economies. Thereby produced goods can better succeed in regional trade areas. This compounds the redistribution. As in the past, the relocation of manufacturing facilities, for example to China, has helped create know-how and supported the further diversification of the receiving economy. Some companies could move completely to an emerging economy if Europe becomes only one of many distribution markets. Industrialized nations are under increasing competitive pressure. These developments will, according to the Stolper-Samuelson theorem, further reduce employment and thereby further burden our social system.

The change described has been ongoing for several decades and will continue for several decades. The BRIC economies share of global GDP will more than double from 2010 to 2020. From the perspective of investors with interest in solid net worth creation, emerging markets are not a trend, or just hype. For a number of years, emerging markets have been part of institutional portfolios, and increasingly private investors are considering emerging markets. Portfolio diversification and yield management are the main benefits.

1. V. De Ruby and J. Debnam, “Does Government Spending Stimulate Economies?,” Mercatus on Policy No. 77, George Mason University (July 2011).

2. J. Rubin and B. Tal, “Will Soaring Transport Costs Reverse Globalization?” StratEco, CIBC World Markets Inc. (May 2008).

3. V. A. Ramey, “Identifying Government Spending Shocks: It’s All in the Timing,” NBER Working Paper No. 15464 (October 2009); R. Barro and C. J. Redlick, “Macroeconomic Effects from Government Purchases and Taxes,” NBER Working Paper No. 15369 (September 2009).

4. J. E. Stiglitz, Globalization and Its Discontent (New York: W.W. Norton & Company, 2002).

5. Dani Rodik, “The Inescapable Trilemma of the World Economy” (June 2007), www.rodrik.typepad.com.

6. JP Morgan, “EM Moves into the Mainstream as an Asset Class,” JPM Emerging Markets Research (October 2010).