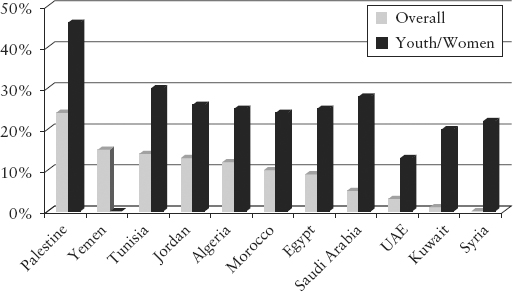

FIGURE 10.1 Overall and Youth/Women Unemployment—MENA

Source: The Arab World Competitiveness Report 2011–2012, author’s analyses.

Following the first oil crisis in 1973, the hydrocarbon-rich countries of the Middle East and North Africa (MENA) received a significant boost to their economic development efforts. The oil and gas price development over the past twenty years created very significant capital surpluses in some of these economies. Today, several MENA countries are among the richest nations per capita, the sovereign wealth funds are among the biggest globally, and mega-infrastructure developments and plans are prevalent. Growing economic relationships and interdependence provide for a springboard and opportunity for all MENA nations and thus MENA represents significant regional and country specific opportunities for investors both in private and in public equity and increasingly in debt markets.

However, business in these countries is not always easy and is dominated by cultural and geopolitical considerations. This greatly impacts the status and outlook of their capital markets.

We consider the soft side of the business environment and prevailing business challenges in the region. They determine the attractiveness of investor markets. More specifically, we review Oman as well as the United Arab Emirates (UAE) as case studies of markets that are currently not classified as emerging but have many of the characteristics of a developed market. It is but a question of time until some of these markets will migrate towards advanced emerging, possibly developed market status, and would become more mainstream as investment targets.

Andreas Buelow

MENA, the Middle East and North Africa region, is usually defined to encompass the Arabic speaking countries in North Africa, the Levant as well as those on the Arabian Peninsula. These countries are interesting developing markets, some classified emerging and some frontier, due to their geographic location and their demographic composition as well as the need to develop sustainable economies based on real value creation. At the same time, some of the countries have particularly interesting characteristics for prospective investors, such as the size of their domestic market (e.g., Egypt) or their abundant wealth in natural resources (e.g., the Gulf states) which in turn provides governments with sufficient funds to offer a wide range of incentives to potential investors. Investing in this region brings about specific challenges related to the prevalent cultural and business environment, as is the case for any other developing market.

These challenges provide a natural barrier to entry for some of the less skilled or courageous investors and overall, the above-mentioned factors combine to make the MENA region an attractive investment destination with substantial potential and limited competition. The comments offer a high-level understanding of the important issues any foreign investor needs to keep in mind when doing business there.

The common denominator for grouping specific countries in the MENA region is the common cultural base they share in terms of language, religion, and history. Due to the geographic location and the historic context of the Ottoman Empire, the region has been a crucial business link between Asia, Europe, and Africa throughout the centuries. Within this line of tradition, countries such as the United Arab Emirates have strengthened their position as global logistics hubs for the endless flows of goods and customers between Asia and Europe. At the same time, the Arab countries of North Africa have deep-rooted trading connections to their southern neighbors in sub-Saharan Africa.

Therefore, the countries of the MENA region do not only represent markets in their own right, they also open doors to other attractive or potentially attractive developing markets. However, the MENA region is not legally one single market, unlike for example China or India, and the legalities of doing business throughout the region are complex and require a well-thought-out structure to access the full potential of the region.

Many if not all countries of the MENA region show a demographic composition where a high and increasing percentage of the population is young. Some estimate that, for example in Egypt and Saudi Arabia, about 50 percent of the population is younger than 25 years. This immediately translates into a burning need for the creation of substantial employment opportunities for the young generation. Adding further fuel to this fire is the fact that many of the young generation are fairly well educated and are looking for challenging and well-paid jobs. The sheer size of the demographic development also means that even the richest of countries, such as Saudi Arabia, will not be able to continue compensating the demographic development with the creation of government sector employment; the problem is just getting far too big. Therefore, the demographic development in the MENA region provides a very tangible need for the economic development of the countries in this region.

Also, the economic basis of many countries in the Middle East and North Africa has been mostly trade for many centuries. It only changed to natural resources over the course of the past 70 years. Trading posts along the main trading routes, many of which led through the MENA region in the past, were crucial for supplies in the days when trade relied on sailing ships and caravans to bring goods from Asia to Europe and vice versa. The small margins made at these trading posts were sufficient to sustain the modest standards of living of the relatively small populations there.

The discovery of oil and gas resources changed this dynamic suddenly as huge wealth was becoming available from exporting these natural resources. This triggered the aforementioned demographic development as well as the development of a modern infrastructure that starts to absorb substantial portions of the otherwise unproductive wealth creation from natural resources in a bid to transform the short-term wealth into a base for a long-term sustainable economy.

Along these lines, many countries have embarked on programs to diversify their economic base away from natural resources, for example by developing manufacturing industries or by creating the framework for knowledge based economies. All these steps are accompanied by financial as well as non-monetary incentives for foreign investors to induce foreign direct investments. In other words, the existing and emerging opportunities are further enhanced by governmental support for utilizing them.

These arguments make a case for the attractiveness of the MENA region as a destination for emerging market investments. The main driver is the need for economic development to provide jobs and to ensure that created jobs remain sustainable in the long-term economy, in addition to the attractive geographic location. Even though they are not a legally integrated market, common language, culture, and history bind the MENA region essentially as one market. Goods and services that are being sold successfully in one market can be exported into other markets using the same sales approach. In the case of the countries of the Gulf Cooperation Council (GCC), which is composed of Bahrain, Kuwait, Oman, Qatar, the United Arab Emirates, and Saudi Arabia, exports are further facilitated because these countries have implemented a fairly strong customs and economic union which allows for easy exports from one member country to another. This large and common market allows any investor to select a suitable country as home base in order to maximize initial market potential as well as government support in a bid to reduce the overall risk of the investment.

This strategy has been used by industrial investors, that is, companies that expand into the MENA region within the context of their international growth strategy. Some German companies, for example, have recently established after-sales operations including limited manufacturing of spare parts in the Kingdom of Bahrain to cater to the Gulf region. Another example is global insurance companies who have pursued a hub strategy, basing themselves in one country and subsequently branching out to other countries in the MENA region to minimize overall capital requirements for their operations in the region. All these approaches require careful due diligence to assess issues such as legal implications, import and export duties between countries of the MENA region, and many other points, in particular when looking at countries outside the GCC. Of course, to the investor, the question of the home base is more a question of foreign ownership regulations, international accessibility of the chosen location, and proximity to the investment targets to maximize control.

Just as any other emerging market, the MENA region holds its own specific challenges for international investors. The three most important points, those most antithetical to the Western business approach, in the Arabian cultural context are the meaning of time, the role of personal relationships with local partners, and the fact that connections are often more important than the letter of the law.

To start with the meaning of time: There is somewhat of a relaxed attitude on the matter of punctuality, be it for meetings or project milestones. While this is less of an issue in countries with strong cultural or historic ties to Europe, such as Tunisia or Lebanon, it certainly requires much patience from an investor who is used to Western business practices. Investors who have to rely on a local partner for their investment or who wish to financially involve a local partner in their investment project, for example for co-funding, need to be aware that decision-making processes will take substantial amounts of time and meetings, despite the fact that the local contact will always be very optimistic that the decision is about to be taken.

In the case of companies, this has to do with their highly hierarchical setup where all decisions must be approved by the top echelons; in the case of private individuals or families, decisions are usually taken after extensive consultation with family members in order to ensure the buy-in of everyone who is affected by the decision in question. It is clear that in this environment, planning also retains a lower priority and adjustments to structures or time lines of projects or investments are frequent. There is also a link to religion, which strongly permeates all Arab societies, and the concept of God’s willingness (insha’allah).

Looking at this from a different viewpoint, however, shows that professional foreign investors can add value above and beyond the investment itself by transferring skills and process knowledge, and such transfers are highly welcome in the drive to modernize the economies.

The importance of personal relationships in the Arabian world cannot be overestimated, as they have been the basis of successful business dealings between the often far-apart countries over the centuries when communication was slow and arduous. Suffice to say that the payment method of using checks was invented by Arab traders in the Middle Ages in order to facilitate trade, for example between Cordoba in Spain and Damascus in Syria. These days as in the past, the importance of trust and a personal relationship between business partners is deeply engrained in individuals from the Arab world. They usually will spend significant amounts of time to get to know potential business partners and to build a personal relationship well before engaging in meaningful business. However, once mutual trust has been established and a sustainable personal relationship has been built, business will develop rapidly as a result of having cemented the personal relationship.

In developing business, the Arab partner of an investor or businessman will use his connections, or wasta, to the benefit of the partnership combined with the reputation and skill of the foreign business partner. It is important to notice that such connections are often much more important than any written agreements. A powerful partner will be able to get special permission to do this or that, simply on the basis of his own personal relationships that have often been developing over generations between different families. Unfortunately, it is ex ante very often much less clear how powerful a potential business partner truly is. This demonstrates the particular importance of doing due diligence on potential business partners in the Arab world, who are often introduced by referral through gatekeepers, people who have a standing agreement with local businessmen to introduce potential foreign investors and business partners to them.

The challenge is to identify early the truly valuable local partner and to avoid the partner who talks but will not deliver, in order to save time and money in relationships that do not bring about business, even though they result in many interesting conversations over coffee. Of course, a track record of successful partnerships in the past is an important indicator in this regard. Other quintessential items when doing due diligence on a potential partner include background checks with international chambers of commerce, a review of local and regional press, and other means of gathering information on the successful execution of projects. A subtle look at the photo gallery in the office of a potential business partner will often reveal the extent to which the individual has particular contacts in the political establishment of his/her own country or experience abroad.

Ignoring the softer aspects of conducting business in the Middle East causes frustration and ultimately defeats many worthwhile investments. With some appreciation of the inherent culture, this region deservedly ranks among the more promising investment destinations in the coming decade.

Many economies in MENA benefit from significant natural resources. The resulting higher share of foreign direct investment and the growing national income allowed farsighted governments to provide conditions for exceptional growth and development, resulting in several economies of the highest standard. Most of the successful economies invest heavily in domestic physical stock; they create favorable framework conditions and infrastructure for private businesses and enterprises to grow. These economies, by definition, find a way to open their economy to external capital and labor flows without endangering their national cohesion and identity.

The less successful economies and economies with no resource incomes foster large government-related or cosponsored enterprises largely in asset based industries. They devote fewer resources to building conditions for private business growth. They are less open economies and retain a number of protective and restrictive conditions on external capital and labor flows.

In addition to economic strategies, labor market conditions divide the region. Several of the MENA economies, mostly the GCC countries, have relatively small indigenous populations and depend on major, low-cost labor imports. The extensive import of low cost labor allowed the building of sizable physical stock at relatively low cost. It also led to a construction boom and real estate bubble. However, the resulting infrastructure in the GCC economies, for example, is well ahead of general economic development.

Other economies provide high public employment, public investment, and subsidies as well as projects to satisfy a large, indigenous workforce. Both labor importers and public employers in their own way created a protective umbrella for the local population. Labor-importing countries created a wage premium for nationals1 and to some extent for entrepreneurs while labor-abundant countries allow dominance, possibly a wage premium, through public and sponsored employment.2

Work-seeking young people and women cannot be absorbed by either continued infrastructure projects or public employment. Widespread unemployment among youth and women in MENA countries is the consequence (see Figure 10.1). Unemployment or lack of prospects for employment among lower-skilled labor was one of the reasons for the Arab Spring.

FIGURE 10.1 Overall and Youth/Women Unemployment—MENA

Source: The Arab World Competitiveness Report 2011–2012, author’s analyses.

In economies with flexible labor markets, unemployment tends to be higher among better-educated nationals and low among laborers. The growing segment of well-educated nationals and women find it increasingly hard to compete with imported labor that often accepts lower wages. In economies with more rigid labor markets, unemployment tends to be higher within the unskilled workforce and women, partly driven by cultural considerations.

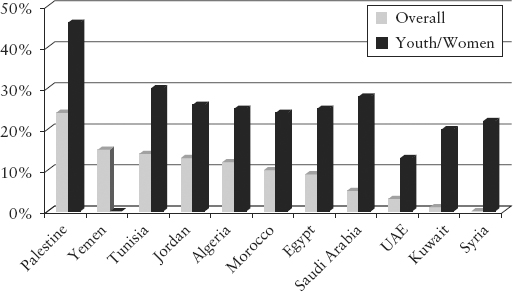

As a transitional strategy both approaches may have their validity but the demographic structure of almost all MENA countries presents a major challenge. The average median age across all MENA countries is 25, well below other regions (see Figure 10.2).

FIGURE 10.2 Average Median Age

Source: The Arab World Competitiveness Report 2011–2012, International Financial Reporting Standards.

The OECD MENA Investment program estimates that in order to maintain current employment levels, 25 million jobs will need to be created over the coming decade. The World Bank even suggests that the region will need to create at least 50 million jobs to maintain social and political stability.3

In effect, both labor market strategies reduce skills competition. The motivation for the local workforce is to join local business leaders, aspire to participate in the leadership of local organizations or be the sponsors or partners of foreign businesses in countries where labor and skills imports are relatively free. Alternatively in countries with an abundant local workforce, locals join public or government/ruling/leading families related enterprises or participate in public employment programs.

Either way, the development of private enterprise, the only sustainable job creation engine of the economy, suffers greatly. Employment growth in the public sector or in the government/ruling family related sector is limited. The solution to the unemployment issue lies in fostering private businesses. In this respect, MENA countries, in particular those with less open economies, lag considerably.

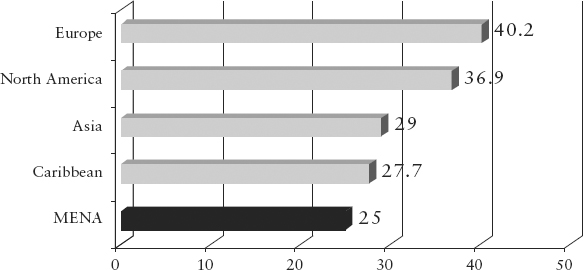

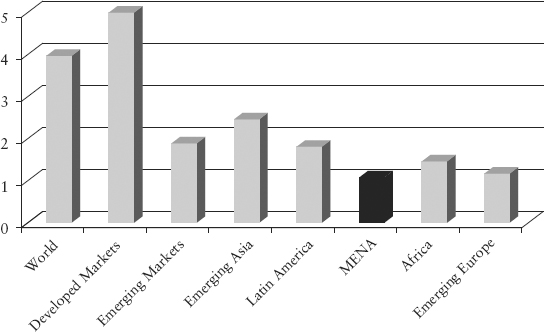

Entrepreneurship is limited in many MENA economies. The World Bank Group Entrepreneurship Survey shows that firm density, that is, the number of new limited companies per 1,000 working population, is a fraction of that in developed and emerging economies (see Figure 10.3).

FIGURE 10.3 Firm Entry Density by Region

Source: The Arab World Competitiveness Report 2011–2012, International Financial Reporting Standards.

Entrepreneurial activity is both more cumbersome due to a regulatory burden and seen as less attractive as compared to public/ruling family related jobs with prestige and some employment security. The low female participation rate and cultural barriers also contribute to a lower entrepreneurial activity.

Business flows generally precede capital flows. As a consequence, business barriers have a significant effect on capital flows and thus attractiveness of markets to investors. The most open business environments generate the most attractive companies and provide both public and private investment opportunities. To assess the outlook of the numerous stock exchanges in the MENA region, we need to consider prevailing business environments as well as restrictions and barriers.

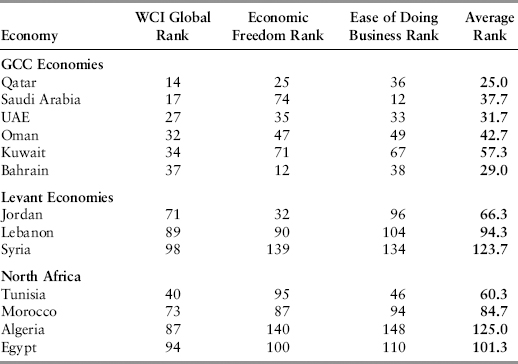

The MENA region can be divided into three subgroups: GCC, North Africa, and Levant. The major countries in each subgroup earn mixed rankings in their global competitive position and with respect to ease of doing business, as depicted in Table 10.1.

TABLE 10.1 Global Competitiveness Ranking 2011/2012: Ease of Doing Business and Economic Freedom of Key MENA Economies, 2012

Source: The Arab World Competitiveness Report 2011–2012, author’s analyses.

Clearly, GCC economies lead the rankings in MENA. The most consistently ranked economy is the UAE, followed by Qatar and Bahrain. Outside the GCC, Tunisia and Jordan come closest at around the level of Kuwait but remain a sizeable step behind the leaders.

Still, GCC economies sport significant barriers to business. Although different from country to country, they are predominantly in the areas of:

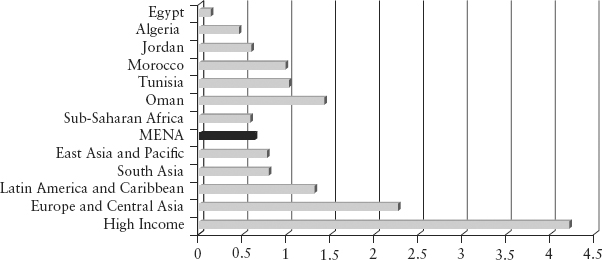

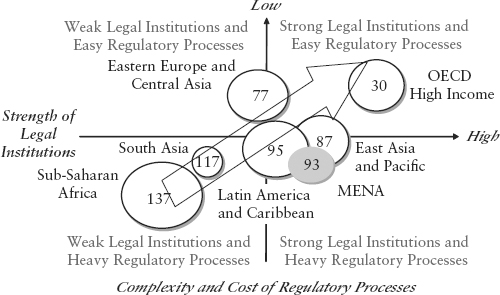

Overall, MENA countries are reducing barriers to businesses for both locals and foreigners but many still suffer from restrictive framework conditions (see Figure 10.4).

FIGURE 10.4 Legal Institutions and Regulatory Processes by Region, 2012

Note: The numbers in the circles Indicate the average ranking; circle size is indicative of the number of economies.

Source: IBSD/WB, Doing Business 2012, October 2011, author’s analyses.

On average, MENA economies are improving business conditions faster than regulatory ease. The legal institutional framework is still weak.

These general business conditions are of relevance to the market investor. First, many of the businesses listed are government or ruling family related. Second, the relative lack of entrepreneurship in some countries leaves the supply side of companies to be listed somewhat wanting. Finally, the lack of sound legal access conditions leaves the investor with an increased risk or overreliance on relationships when businesses face disputes or restructuring. Several recent high profile cases attest to this risk.

Given the available wealth and investment appetite, MENA region stock markets, in particular GCC stock markets, should become one of the most attractive future emerging markets. Economic growth (see Table 10.2), even taking into account the Arab Spring and slowdown of developed economies on which the region somewhat depends, is projected to be consistently high, except for Egypt, and rising resource prices should ensure increased revenues for most of the MENA economies, as well as the freedom to make necessary investments.

TABLE 10.2 IMF September 2011 Growth Forecast for 2012

Source: The Arab World Competitiveness Report 2011–2012, author’s analyses.

| Algeria | 3.3 |

| Bahrain | 3.6 |

| Egypt | 1.8 |

| Jordan | 2.9 |

| Kuwait | 4.5 |

| Lebanon | 3.5 |

| Morocco | 4.6 |

| Oman | 3.6 |

| Qatar | 6.0 |

| Saudi Arabia | 3.6 |

| Syria | 1.5 |

| Tunisia | 3.9 |

| UAE | 3.8 |

Most forecasts by financial institutions and regional research houses put growth at 1 to 2 percentage points higher for most economies. Resource prices could add another 1 percentage point of growth. Necessary conditions are the continued development of institutional framework conditions, increased legal certainty, and investment in human resources.

Some of the MENA economies, in particular the Levant economies and some North African economies, face specific challenges that may reduce overall attractiveness of their stock markets until their domestic economy and private business orientation gets into full swing. They also tend to have smaller stock markets and attract less foreign investment.

Capital markets in general, covering banking, debt, and equity markets together, are relatively less developed in MENA than in other regions (see Figure 10.5).

FIGURE 10.5 Capital Markets as Percentage of GDP by Region

Source: IMF, Emirates NBD Research, author’s analyses.

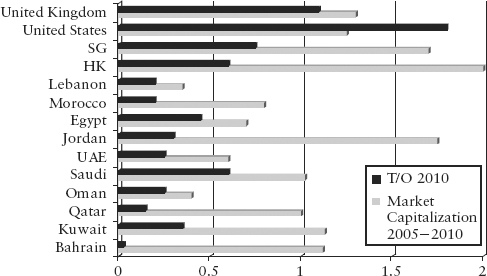

MENA capital markets are most dependent on bank loans and utilize bonds least compared to other regions.4 Equity markets in MENA as a region are relatively smaller than in other regions. This is despite the fact that GCC exchanges are not much less capitalized in proportion to their GDP than developed economies. Selected other MENA markets also sport high market capitalization to GDP (see Figure 10.6).

FIGURE 10.6 Capital Markets as Percentage of GDP by Economy

Source: US Census, IMF, Emirates NBD Research, author’s analyses.

However, the liquidity gap between them and other markets is great. This liquidity gap is a function of the type of companies listed—concentrated ownership by government and families—and the nature of the stock market (little free float required) in the GCC and other MENA economies.

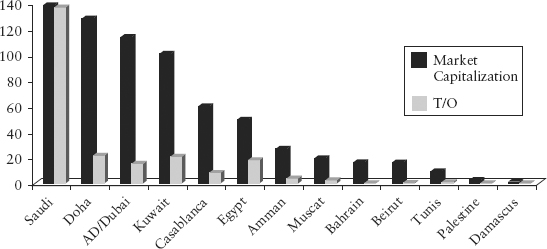

Overall, all MENA stock exchanges amount to around US$1trillion stock market capitalization (see Figure 10.7). This is less than 2 percent of global market capitalization but a very credible and important share of 14.3 percent of all stock markets outside developed and BRIC economies. Continued economic growth and development potential makes the MENA region a very attractive capital destination in the coming years.

FIGURE 10.7 MENA Stock Markets Capitalization at End of 2011 and Turnover in 2011 (in US$ millions)

Source: Arab Monetary Fund (www.amf.og.ae) and Arab Capital Market Resource Center (www.btflive.net), author’s analyses.

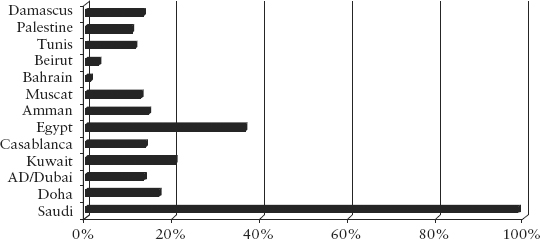

The relatively tightly held equity of most companies still represents the major barrier to larger scale foreign investment. As a consequence, liquidity remains a major issue for investors (see Figure 10.8).

FIGURE 10.8 MENA Stock Market Liquidity Percentages of Market Capitalization at End of 2011 by Individual Market

Source: Arab Monetary Fund (www.amf.og.ae) and Arab Capital Market Resource Center (www.btflive.net), author’s analyses.

For the major economies, the attributes of stock exchanges required to qualify as frontier or emerging economies based on the definitions of major index providers are largely met. They are however not the real issue.

Either current companies allow more float of their shares or new companies need to be listed providing attractive investments with enhanced liquidity. Otherwise, MENA stock markets, while important in their own right, may not fulfill their promise of becoming major investment destinations for foreign and domestic investor capital.

Mohammed Moussallati

The Sultanate of Oman, with a population of over 2.3 million, is the second largest Gulf state, spanning a total area of over 300,000 square kilometers.5 HM, the Sultan, Qaboos bin Said Al Said, has since coming into power in 1970 overseen political stability, vast infrastructural development, and economic growth.

As an indication of the level of Oman’s progress, the United Nations Development Program named Oman in 2010 as the most improved nation during the preceding 40 years among 135 countries worldwide, progress which is not simply attributable to oil and gas earnings, as some might assume.6

Recently, Muscat, the capital city of Oman, was voted second best city to visit in 2012. Oman has thus become an attractive major destination for international visitors mainly due to the achievement of immense, almost Dubai-style local development while maintaining very much of a traditional feel.

Recent attractions include the opening in October 2011 of the highly anticipated Royal Opera House in Muscat, equipped with state-of-the-art technology and presenting internationally renowned performers; November 2011 saw Oman’s first floating hotel on a ship, named Veronica, stationed at Duqm and equipped with luxury entertainment facilities. Such initiatives continue to boost Oman’s global profile and play a major part in encouraging tourism and foreign investment, part of His Majesty’s key policy to reduce Oman’s reliance on oil-related income.

Indeed, fueled by rising oil prices in the international markets and a stable political and economic setting (in comparison to other Arab countries), Oman has seen massive growth and investment by the local government and private sources as well as foreign investment, which is expected to continue. In fact, it is reported that the Omani government had forecasted investment of RO 37.5 billion (approximately US$97.5 billion) for new projects in Oman for the period 2011–2015.7

The legal and regulatory system in Oman is also well developed and orientated toward attracting foreign business and the best individual talent from abroad. As lawyers are seeing an increasing number of foreign businesses looking to establish a presence in Oman and accordingly seeking advice on a wide range of matters, such as Omani laws pertaining to foreign investment and public procurement and regulations applicable to specific industry sectors, with the prospect of privatization in industries (such as power, water, electricity, telecommunications, and aviation) being an attractive opportunity to local and international investors. Potential investors are also seeking advice concerning the most suitable structure for their specific needs to engage in business in Oman.

Oman’s constitution, issued on November 6, 1996 and titled “The Basic Law of the Sultanate of Oman” (“Constitution”),8 provides certain key guarantees that are fundamental to the confidence in and development of the Omani economy, including the protected right for individuals to litigate (Article 25), the rule of law and the impartiality of judges (Articles 59 and 61), and the independence of the Omani courts.

The growth in foreign investment into Oman is well documented, driven by the government offering various incentives for foreign investment, including the freedom to repatriate capital and profits and the availability of soft loans with favorable interest for certain investment projects, not to mention a thriving economy. A number of government-established organizations have been formed to facilitate foreign investment, such as the Public Authority for Investment Promotion and Export Development (PAIPED), which renders services such as the provision of investment information, assisting foreign investors to find suitable local partners, and obtaining various government approvals and finance from government and local banks.9 The free trade agreement signed between Oman and the United States, which took effect at the beginning of 2009, eliminating tariff barriers on all consumer and industrial products, also provides strong incentives and protection for American businesses investing in Oman.

A number of business structures are available for foreign investors seeking to engage in local commerce, including limited liability companies, joint stock companies (the equivalent of public limited companies in other countries), commercial agencies (allowing a local agent to sell, promote and/or distribute products and/or services of a foreign entity with otherwise no legal presence in Oman) and commercial representative offices (put simply, a marketing branch of a foreign entity, but which cannot contract or engage in sales activity directly). Oman is becoming accustomed to world-renowned brands in its cities. By way of example, Oman’s Saud Bahwan Group, with a presence in a diverse range of industries (including oil and gas, property and real estate, travel and tourism, heavy vehicles, industrial and construction equipment, and automotive), holds the agency for leading brands in the automotive sector, including Toyota, Daihatsu, Lexus, Kia, and Ford, and MAN and HINO brands in the heavy vehicles sector. Other popular brands that can be seen in Oman include food chains like McDonald’s, KFC, and Nando’s, and international hypermarket chains such as Carrefour.

With the priority of the government to diversify and reduce reliance on oil income as the largest sector in the economy, Oman is seeing rapid industrialization and growth in sectors such as tourism, agriculture, fisheries, education, health, and communication. The government encourages industrial production that is export-orientated, resulting in greater local manufacturing of a variety of high-tech products. For example, OCTAL, which is considered to be the largest PET resin manufacturer in the Middle East and the largest integrated PET sheet manufacturer in the world (PET being a highly valued packaging material), has its production facilities in the Omani port city of Salalah. It is reported that approximately 59 percent of Oman’s gross domestic product (GDP) is generated outside the oil and gas sector, and this is expected to increase as the government, through its implementation of a series of five-year development plans, continues its policy of encouraging private sector investment into non-oil and non-gas industrial activities.

Other ventures of the Omani government include Oman Brunei Investment Company SAOC (OBIC), a special investment company owned jointly by the governments of Oman and Brunei Darussalam, which invested significantly in Oman. Such foreign and local investment is the cornerstone to greater competitiveness, productivity and quality of service, and advancement in technology.

There is still of course an element of protectionism in favor of locals. For example, the Foreign Capital Investment Law in Oman (Royal Decree No. 102/94) prohibits a non-Omani individual or entity from holding more than 49 percent of the share capital of an Omani commercial company (although experience has shown that in practice it is possible for up to 70 percent of foreign ownership to be authorized). The substantial capital requirements when incorporating commercial companies in Oman (for example, the requisite capital for a limited liability company with foreign shareholding requires capital of not less than RO 150,000, (approximately US$390,000) also provide a safety barrier for local creditors against unscrupulous foreign investors.

Examples include, among others, Oman’s membership of the Berne Convention since July 1999 (protection of copyright works), the Madrid Protocol (facilitating the international registration of trademarks), the Paris Convention since July 1999 (protection of industrial property), the Patent Co-operation Treaty since October 2001 (harmonization of patent application process for inventions in contracting states) and the Trademark Law Treaty since October 2007 (harmonization of the trademark application process).

In order to implement the provisions of the relevant international treaties, conventions, and protocols, Oman has enacted local legislation to protect intellectual property rights, including dedicated laws to protect copyrights (Royal Decree No. 65/2008), and geographical indications, industrial designs, industrial property, patents, trade names, trademarks, and trade secrets (Royal Decree No. 67/2008). This comprehensive legal framework provides important recourse for local and foreign entities against abuse or misuse of their valuable intellectual property by unauthorized third parties and a level of comfort which encourages their establishing of a commercial presence in Oman.10

In May 2011, the Central Bank of Oman approved the establishment of exclusive Islamic banks and windows (or branches) of existing licensed banks to conduct the business of Islamic banking/finance (in other words, banking which is Shariah-compliant). The expectation is that the move will encourage locals to hold on to their savings and invest in Oman, or to repatriate funds already abroad, as they would no longer need to invest in other countries which offer Islamic banking/finance products, and also to attract foreign investors.

Companies in Oman are able to retain the best local talent and also attract the finest foreign talent from some of the leading educational hubs in the world, including Australia, the United Kingdom, and North America, among others. As employees, the attraction is zero income tax coupled with relatively high salaries, cheaper living costs (for example, subject to daily price fluctuations, gasoline in Oman costs approximately US$0.25 per liter), a warm climate, beautiful wadis, deserts, beaches, and mountains, excellent schools, hospitals, sports facilities, and shopping malls, as well as a friendly local population.

An added comfort for non-Omani individuals working in Oman is the employee-favorable Omani Labor Law (Royal Decree No. 35/03 as amended) and accompanying ministerial regulation. Local cases demonstrate that lawyers have successfully advised a number of aggrieved non-Omanis who, as in any other so-called developed country, are seeking to enforce certain rights against reputable local organizations that are incompliant with the labor law. The Omani courts have shown that, in accordance with the Omani constitution, judgments are compliant with the law, and this provides added reassurance to non-Omanis who leave secure jobs in their home countries to work in Oman.

Rising oil prices in international markets and the stable political and economic setting in Oman coupled with a well-developed legal and regulatory system have attracted significant local and foreign investment (public and private). Oman is becoming less reliant on oil- and gas-related income, in accordance with government policy, and is seeing growth in other sectors such as tourism, agriculture, fisheries, education, health, and communication; in addition, the quality of services, productivity, competitiveness, and advancement in technology continues to improve. This progression is attributable to Oman’s ability to attract fine foreign talent and significant investment incentives and protections, including a comprehensive intellectual property framework.

Oman has a comparatively long history in securities trading. The Muscat Securities Market (MSM) was established by Royal Decree (53/88) in 1988.11 After 10 years of continuous growth, Oman promulgated the new Capital Market Law in 1998 which separated the exchange, the Muscat Securities Market (MSM) where all listed securities are traded, and the Capital Market Authority (CMA). The Exchange is a government entity, financially and administratively independent from the regulator but subject to CMA supervision.

For a listing on the regular market, companies must have a solid record of profitability. The parallel market has lower requirements and the third market consists of companies facing financial difficulties. Listed companies are from three sectors: banking and investment, services and insurance, and industry.

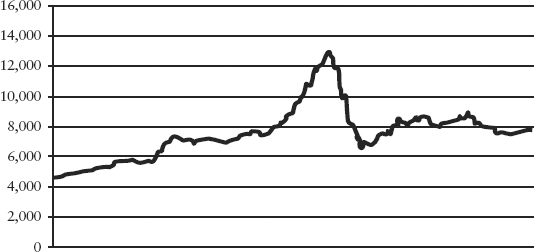

The MSM index, the MSM 30, includes freely available shares and a 10 percent capping to ensure wider representation of smaller companies. The free float and capping is revised (reset) on a quarterly basis and based on market capitalization, liquidity, and earnings per share. The MSM 30 index comprises three subindexes representing the three sectors (banking and investment, industry, and services insurance). Performance has been mixed (see Figure 10.9).

FIGURE 10.9 Muscat Securities Exchange: MSM 30 Index, 2003–2012 (indicative)

Source: Muscat Securities Exchange, Index performance approximated, www.msm.gov.com, author’s analyses.

The trading system from Atos Euronext, France, is highly advanced and ensures the real time provision of data and information to all users. The clearing and settlement system is through a settlement bank (Central Bank) supported by a settlement guarantee fund (SGF).

Incentives for foreign investment in the Oman Capital Market include:

Overall, the MSM is an attractive stock market with a market capitalization in end-2011 of around US$21 billion and a turnover of around US$2 billion. Some 22% of turnover or US$440 million is by non-Omanis indicating solid interest by foreign investors.

The United Arab Emirates (UAE) are a case in point of an economy that successfully addresses the antithesis of the role of the political economy and the success requirements of the private economy. The country excels in both aspects: a strong and often underestimated foundation of the formal economy providing great opportunity for foreign and domestic business, and the often invisible hand of the informal economy that guides much of the commercial activity throughout the country. The UAE has implemented some very advanced solutions to overcoming and mitigating this dilemma that augur very well for rapid progress in international capital markets as and when culturally entrenched impediments are diluted.

Business flows almost always precede capital flows. Selected economies such as Mongolia or for that matter the Emirate of Abu Dhabi with a disproportionate level of natural resource income are an exception. For most economies, entrepreneurs (private or public) drive growth by taking advantage of market inefficiencies and asymmetries to generate profits. They invariably generate and sustain some form of advantage to maintain their gains that competitors cannot match at the time. Whatever the definition of entrepreneurship,12 businesses require favorable framework conditions to succeed.

These framework conditions cover in the most general terms:

The UAE has and is providing such conditions to a very large extent. The economic strategy of the UAE has been to deploy its financial resources and legislative powers in creating first world infrastructures, thoughtful legal underpinnings, and living conditions to attract business flows. The result has been a leading position regionally and globally in several sectors, for example aviation, duty free shopping, airport management, entrepot port and port management, logistics, trading with developing and restrictive economies, retailing and tourism, shipping services, and maintenance. Equally the small and medium business sectors operating domestically find a conducive environment to conduct their business.

For foreign businesses, there are hardly any market access restrictions but the UAE maintains controls of ownership. To mitigate this necessary limitation since the local population is only a fraction of total population, free zones and exempted business locations were created. In effect except for solely onshore business, foreign businesses can own and operate under their sole control. Even for onshore business, the sponsorship system allows effective if not legal control by the foreign party. Due to this ownership constraint, the UAE receives lower scores in most global rankings than it would otherwise achieve. This may be formally justified but does not reflect practicalities. Influence of course remains a core matter reserved for locals. While the outstanding hospitality of the country and its inhabitants provides a false sense of importance to foreigners, true influence requires longstanding relationships and is always a derivative of such relationships with locals.

The legal framework is by most standards well equipped to handle the needs of the business community. Certain traditional constraints such as for agencies, immigration, and long-term resident issues as well as bureaucratic impediments or practices exist but are not much different than in many of the advanced emerging or even some developed economies. The corollary of a decent legal system is redress and dispute resolution. In this respect, the UAE has made another stride and allows businesses to choose the jurisdiction of the Dubai International Financial Centre (DIFC) and its courts, a leading court with some of the most prominent international judges adjudicating cases. Moreover, the DIFC has developed an arbitration center together with London that equally provides for professional and well-managed solutions to commercial disputes. This makes Dubai and the UAE unique in terms of enabling business conditions. In all practical aspects the UAE is an advanced emerging market.

At the same time, UAE sovereign wealth funds are among the largest single financial investors globally with an estimated more than US$1 trillion in foreign investments. This outward investment strategy has given the UAE access to global brands, technologies and corporations.

The potential of the UAE of joining the formal ranks of an emerging or advanced emerging economy is evidenced both by its business success and its rapidly developing framework conditions. Similar to Hong Kong, which developed from a “barren rock” (as British envoys in the early 1800s described Hong Kong), the UAE has created an enviable position starting from a traditional trading post and port surrounded by desert to become one of the most attractive cities to live in and transact business.

The reason why international investor acceptance has lagged lies in two factors: One, capital markets are relatively under-developed—the major criteria for becoming an emerging economy—and, two, influence and power, in essence the ability to make things happen and resolve issues, lie squarely with the leading local families and culturally related Arab entrepreneurs from the GCC and the region.

While stock market capitalization to GDP is similar to that of Germany, liquidity and free float is a fraction of Germany or the average developed world. Tradable instruments are limited and although new commodity and currency contracts are being introduced on the commodities exchanges, liquidity remains the core limitation. This liquidity gap is closely related to the strong retention of sole influence by local families. Control (anti-dilution) objectives, modest transparency and disclosure willingness, and the need for external recognition regardless of the substance are some of the barriers to increased global capital flows.

Family and clan issues and relationship histories prevent many rational commercial decisions. There is close to no appetite from leading entrepreneurs to relinquish any form of influence to outside shareholders. This results in some dysfunctional corporate governance and may demotivate international investors.

At the same time, large local entrepreneurs dominate the asset-based industries and invest with very high gearing. High skills businesses are rarely the domain of local families. Local banks also rather support the local asset based businesses very often well beyond prudent bank exposure. Therefore third party equity in more formal markets—private or public—becomes a distant second choice for funding. Debt markets are expensive and only economical for larger issues. Thus the debt market is dominated by sovereigns and government-owned entities. Some disasters with property related finance has not helped the debt market development.

The UAE has the businesses and the capital to develop a strong stock market—leaving aside the detrimental competition between Abu Dhabi and Dubai—if local families are willing to become smaller shareholders in bigger businesses and adopt international corporate governance standards. When this happens, the UAE could be at the forefront of a booming stock market—certainly it could figure among the global fifteen or twenty largest markets in particular if the UAE were to become the springboard for regional economies with less developed infrastructures and lower political stability. It is much a function of cultural and historic impediments that should be decreased by gradual action of the government on the legislative side and the institutions on the market side. Entrenched local protection does not serve international capital markets well and while the potential is there, the choice is entirely up to the ruling family, the administration, and the leading entrepreneurs in the UAE.

Overall, the wider MENA region is one of the most attractive investment destinations. Although the region shares a cultural affinity, its components are distinctly different. In particular the GCC economies are well advanced.

As with many other crises, the Arab Spring led all governments to institute reforms and increase their investment programs as well as investing in their people. Most economies and sovereign funds have announced large-scale projects, joint ventures, and development programs that will lead to the continued upgrading of the infrastructure and industry. Liberalization will equally figure on the agenda of many governments. This will, over the coming years, position the core Arab countries as very attractive investment destinations for corporates, possibly private equity.13

To become a preferred investor destination, public capital markets need to change. This will require a fundamental shift in corporate and family attitudes and commensurate regulations of the markets. Huge domestic investment alone cannot bring the GCC countries and some of its neighbors to the forefront for public market investors. Investing in the wider MENA region requires a different approach based on the prevalent cultural and business environment. Specifically, the cultural challenges are the meaning of time, the role of relationships with local partners, and often the dominance of connections over the law. This represents a significant opportunity for those with a deeper understanding of the region but also a considerable barrier for the uninitiated.

MENA stock markets are overall relatively small compared to the economic strength and potential of the region. This has to do with the narrowness of the markets and multiple practical rather than legal restrictions for investors. These markets demonstrate well the need to look at markets beyond overall economic growth potential and stock market attributes. At the moment they display a profound lack of liquidity, yet the opportunity available is probably the size of the Russia, Brazil, or India market or even a combination thereof.

Aside from a thriving economy, the government of Oman provides various incentives to entice foreign investment, including the freedom to repatriate capital and profits and the availability of soft loans in designated sectors. Investors have a number of business structures available to engage in commerce in Oman to suit their individual needs and can rely on a comprehensive regime for the protection of their intellectual property. The recent approval of Islamic financing in Oman and the ability for conventional banks to offer Islamic finance products is also expected to attract greater funds into Oman.

The UAE, with its hubs of Abu Dhabi and Dubai, sports an economy, investment position, and fiscal balance that is generally enviable. Overshadowed by reports on the arguably significant financial difficulties of government-related or connected property groups, the performance of major sectors of the economy and investment potential is underrated. If it were not for liquidity constraints and variety of stocks listed, the stock markets of the UAE could be on the verge of strong performance. As an investment destination, the UAE deserves increasing attention.

1. Government of Dubai, Dubai Economic Council, Migration, Labor Markets and Long Term Development Strategy for the UAE, Dubai (2011).

2. Kito de Boer and John M. Turner, “Beyond Oil: Reappraising the Gulf States,” McKinsey Quarterly (January 2007).

3. The Arab World Competitiveness Report 2011–2012.

4. Tim Fox, Chief Economist Emirates NBD, GCC Economic Overview (October 2011).

5. Ministry of Information, Sultanate of Oman (undated). “Useful Information,” www.omanet.om/english

6. Human Development, UNDP (November 4, 2010). “Five Arab Countries among Top Leaders in Long-Term Development Game,” http://hdr.undp.org/en

7. Ellatari, L. Sultanate of Oman—Major Business Sectors. The Embassy of Switzerland (September 2011), pp. 1–2. Available online: http://www.osec.ch

8. Ministry of Legal Affairs. “The Basic Statute of the State,” http://mola.gov.om

9. See, for example: Holdsworth, P. (10 January 2011). “Foreign Direct Investments in Oman Improved by 128 Percent,” Gulf Jobs Market. Available online: http://news.gulfjobsmarket.com

10. A list of treaties, conventions and protocols to which Oman is a party (including texts) as well as a list of local laws enacted by Oman can be found on the website of the World Intellectual Property Organization (WIPO) at http://www.wipo.int

12. Joseph A. Schumpeter, History of Economic Analysis (New York: Oxford University Press, 1954).

13. Special thanks to Osama Al Rahma, general manager of the Al Fardan Exchange and director of the Al Fardan Group for his continued education and comments on investing in the Arab region.