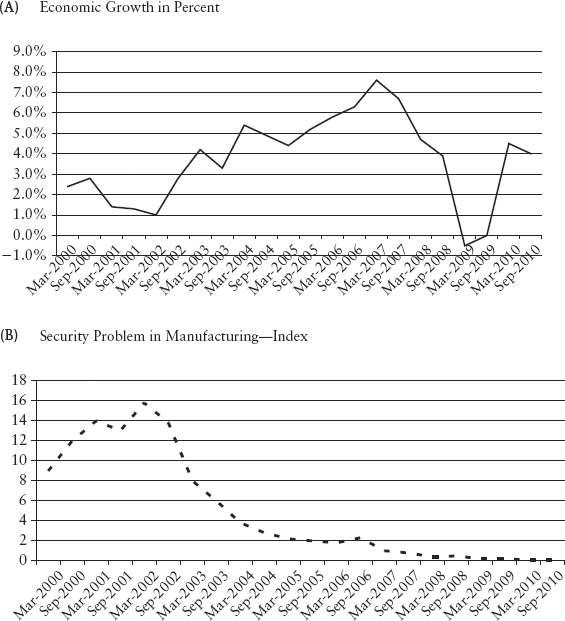

FIGURE 12.1 Colombia Economic Growth and Insecurity Problem

Source: DANE, National Accounts & ANDI, Monthly Industrial Survey.

Many largely unknown markets have potential. Three very different and starkly contrasting examples are discussed here. Colombia, an economy formerly known for its role in the drug trade, is today part of the next wave of South America investment candidates and already on its way to becoming part of emerging markets investment portfolios.

The Republic of Mongolia, until recently not known at all, had a spectacular rise in its stock market during 2010 and 2011 mainly driven by resource exploration companies. Abundant reserves of important commodities have put this country firmly on the map for growing investment, but stability in development is yet a step away. The genesis of the stock market in 1991, namely privatization of state-owned companies into the hands of the population, is an interesting approach to launching a stock market.

Haiti does not even have a stock market and suffered a tragic natural disaster that all but destroyed its economy. Multilateral aid and international support gave this country a new lease on life and with this new start, a small but remarkable player could emerge at the door step of the United States.

These three countries represent the 5- to 10-, 10- to 15-, and 20- to 30-year horizon for emerging market investors. They serve as examples of the genesis of future markets to watch.

Paul Stewart

This review of Colombia illustrates how a country notorious for its armed conflict has evolved into a favorable location for investors to seek lucrative business opportunities. Investors the world over, but most notably from Canada, the United States, and Spain have already acquired assets in a country that is considered part of a new block of emerging markets: CIVETS (Colombia, Indonesia, Vietnam, Egypt, Turkey, and South Africa) predicted by Robert Ward, director of global forecasting for the Economist Intelligence Unit in 2009 to rise in economic prominence over the coming decades.

To the uninformed, Colombia conjures images of drug cartels, terrorist attacks, kidnapping, and guerrillas, perceptions that are all too often reinforced within the media. However, these undesirable elements are more symptoms of Colombia’s past than indications of its future. In reality, peace settlements with FARC after decades of internal fighting have helped create relative stability that can be built on. And now, Colombia is on the cusp of achieving its full economic potential (see Figure 12.1A).

FIGURE 12.1 Colombia Economic Growth and Insecurity Problem

Source: DANE, National Accounts & ANDI, Monthly Industrial Survey.

Colombia is already the fourth largest economy in Latin America after Brazil, Mexico, and Argentina, with strong inflows of foreign direct investment (FDI) that has increased over 500 percent in the past decade from US$2 billion in 2002 to US$13 billion in 2011, of which approximately 85 percent was invested in mining and energy. The increase in FDI has not been all positive; the country’s currency, the peso, has appreciated by 12 percent against the dollar only in 2011, even as the central bank has purchased US$20 million within the currency market to slow its rise. Inflation remains one of the government’s key economic concerns. The central bank has begun raising rates to 5.25 percent due to the decrease in global commodity prices and the economic weakness in China. Government also persuaded the central bank to hold rates steady through the rest of the 2012. Hence, inflation forecast for this year is around 2 to 4 percent.

With the second largest population in South America (after Brazil), with its rich endowment of natural resources such as oil, natural gas, titanium, copper, and coal and with more than 6.5 million hectares for agricultural development, global-investment industry interest is rising.

In 2004, during Álvaro Uribe’s presidency, the government applied a more assertive military policy in the attempt to thwart the FARC and other militant groups. The offensive, supported in part by aid from the United States, improved several security indicators, including kidnappings, which decreased from 3,700 in 2000 to 172 in 2009. The overall reduction (Figure 12.1B) of violence has paved a path toward increased internal travel and tourism, which has helped improve the distribution of wealth to some of Colombia’s poorest citizens. The middle class has increased and become wealthier, according to the World Bank, and Colombia’s GDP per capita has increased 180 percent in the past six years to US$9,800.

The new investment policies of President Juan Manuel Santos, coupled with the country’s ratings upgrade from Standard & Poor’s, Moody’s, and Fitch, have brought additional demand for the country’s bonds and lowered the cost of borrowing. However, in spite of a strong GDP growth of 5.9 percent in 2011, economists predict weaker growth in 2012 due to the sovereign debt crisis in the Euro Zone, high unemployment in the United States, sluggish growth in Japan, and weaker than usual growth in the BRICs.

Colombia is a net exporter of commodities and benefits from high global commodity prices. However, if prices remain persistently high, Colombia could experience a further increase in inflation. If this occurs, the Central Bank will need to take corrective measures in order to stem inflation before it becomes entrenched.

Corruption presents a significant threat to Colombia’s overall economy and its ability to attract foreign investors. Luckily, President Santos has adopted a direct approach to curtail corruption within the government by targeting infrastructure, health services, and the resource royalty management sector, areas of the economy that are deemed the most corrupt. Ultimately, these policies have helped improve Colombia’s ranking in Transparency International’s Index, which measures business transparency in over 180 countries. Colombia ranked eightieth in 2011, only seven places below Brazil (seventy-third), one of the lowest in the region.

Colombia has also benefited from being perceived by some as a good kid in a tough neighborhood. Left-leaning governments in Venezuela, Ecuador, and Bolivia provide Colombia the opportunity to market itself as a beacon of capitalism in a bastion of communism to capture higher foreign investment.

Recently, strong consumer demand and improving labor market conditions have helped drive Colombia’s economy. Retail sales are up 13 percent, and industrial output is up 4 percent year over year as of February 2011. Colombia is one of few countries in Latin America not plagued by hyperinflation in recent history and, besides El Salvador, was the only other country to avoid debt restructuring during the Latin American crisis of the 1980s.

Colombia’s debt-to-GDP ratio (45.6 percent in March 2012) is higher than those of their regional neighbors, but short-term debt as a percentage of reserves is below 20 percent. The country has a current account deficit of US$5.9 billion, or roughly 2.5 percent of GDP, and had $22.5 billion in foreign debt. The government has recently approved a reform package to direct excess oil and mining revenue to a sovereign wealth fund, has reformed the distribution of royalties to regional governments, and has limited the level of debt the government can issue to strengthen economic fundamentals.

Colombia possess a wealth of natural resources including minerals, energy resources (hydroelectric, thermal, wind, and solar power), agricultural products, and fuels, offering investors a range of opportunities.

Colombia has the highest coal reserves of Latin America, mainly concentrated along the northern coast in an open mine called El Cerrejon, that stores 7.42 billion metric tons of coke coal used as a reducing agent in iron smelters. This has brought many big-league investors interested in trading, extracting, and operating mines, such as Glencore and Xstrata, to the country.

Colombian emeralds are considered among the best in the world. Colombia produces 55 percent of world demand for these gems, known for their size and quality. In 2011 Colombia exported US$72 million in precious stones to its main export markets: Japan (50 percent) followed by the United States (25 percent) and Europe (12 percent).

Colombia has about 114.4 billion cubic meters of natural gas reserves. With a pipeline network all regions of the country can be reached. The main pipeline, owned by Ecopetrol (Colombian oil company), extends over 584 kilometers and is supplemented by private pipelines over 1727 kilometers, mainly on the Atlantic Coast and in Santander.

It is estimated that the territory holds about 1.4 billion barrels of oil with a current extraction capacity of over 1 million barrels per day. There has also been an investment in the two main refining plants (Cartagena and Barrancabermeja) to expand their refining capacity and oil quality standards.

There are 32 hydroelectric power stations producing 64 percent (2009) of internal electricity demand and 30 thermal generators covering 33 percent. The other 3 percent is mostly produced by aeolic/wind and solar energy. The construction of an electricity transmission line to Panama, connecting Colombia with Central America, has allowed power exports.

With the recent reduction of guerrilla groups, 6.5 million hectares have been made available for agricultural purposes. This sector currently generates 19.7 percent of employment, 19 percent of exports, and 9.2 percent of Colombia’s GDP. Low land prices and the strategic location have attracted multinationals such as Cargill to start planting 10,000 ha of soy and corn. The government is also providing incentives to agricultural investors such as tax reductions and low loan rates.

Colombia, strategically located between both the Atlantic and Pacific oceans, allows efficient transportation with competitive rates for international shipments3 and the ability to access the North American markets from both the East and West coasts. As it stands, Colombia is only a three- to four- day sail, or a three-hour flight to two of the United States’ largest markets, which provides a significant competitive advantage. This allows Colombian goods to reach major markets faster and at a lower cost.

To incentivize foreign investment, the government has created a free trade zone with a single 15 percent income tax rate. In addition, the government has provided tax exemptions for investments in tourism, aeolic and biomass energy, power generation, and medical and software products.

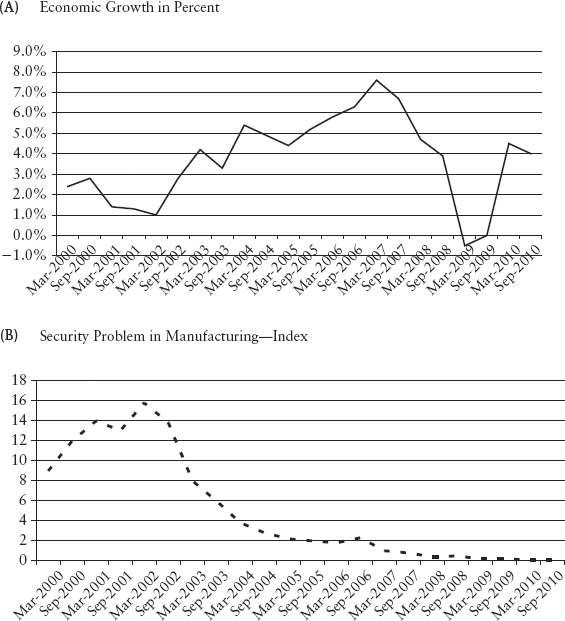

The past 10 years have been marked by the increase of over US$45.4 billion (or 222 percent) in exports, with a noticeable jump in 2008 when exports increased by 55.1 percent over the previous year (see Figure 12.2). According to the National Statistic Center (DANE), the positive trade balance in 2011 was 4.2 percent. Main imports were industrial materials with a 41.3 percent share, followed by construction materials with a 37 percent share.

FIGURE 12.2 Colombia’s Export and Import Trade, 1996–2011

Source: National Accounts & ANDI, author’s analyses.

In 2011, Colombia’s largest export markets included the United States (38.2 percent),4 the Netherlands (4.6 percent), and Chile (4.1 percent) (see Figure 12.3).

Thus, the Colombian economy has become more dependent on other economies. At the same time, the economy is influenced by international prices of commodities, as 57.5 percent of exports are based on oil and mining.

The recent free trade agreement (FTA) between the United States and Colombia, signed in October 2011, establishes tax-free access for most Colombian products exported to the United States, encouraging foreign investors to see Colombia as a springboard to the huge US consumer market. Similar trade agreements have also been concluded with South Korea, Canada, and Panama.

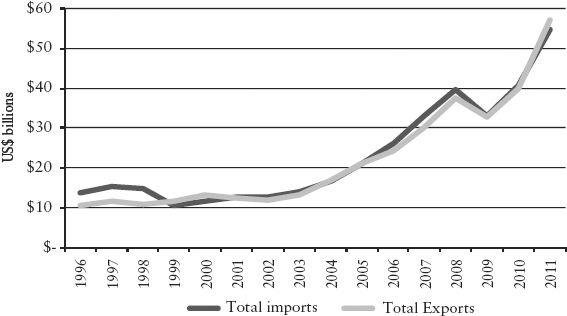

From its beginning on July 3, 2001, the Colombian Stock Exchange has contributed to the growth and development of the Colombian economy, facilitating the financing of industrial, commercial, and service companies that increasingly demand financial resources to further their production (see Figure 12.4).

FIGURE 12.4 Colombia Stock Exchange (BVC) Turnover 2001 (Second Half) to 2011 (in US$ billions)

Source: BVC Report 2001–2011, author’s analyses.

Transactions through the Colombia Stock Exchange (BVC) in fixed income securities and equities totaled COL$1,840.81 billion (Colombian peso currency equivalent to US$1 billion) in 2011. This was lower by 16.9 percent than in 2010, but an increase of over 2,254.7 percent since its beginning in 2001.

Currently only two Colombian companies trade on US exchanges, Ecopetrol (EC) and BanColombia (CIB). Ecopetrol, the state-owned oil company with a market cap of US$85.5 billion, yielded a 27.2 percent return last year and pays a dividend of 5.1 percent. BanColombia, one of the largest banks in Latin America, with a market cap of US$13.1 billion, returned 14.7 percent last year and pays a dividend of 2.2 percent. Two more Colombian companies were projected to be listed on the NYSE this year, EEB and Davivienda (the second largest national bank), but given market turmoil, it seems doubtful they will go ahead.

The BVC (Colombia Stock Exchange) is the stock market with the greatest turnover in the Latin American region. A significant portion of the BVC is composed of government bonds (98 percent), in part because it is the only stock market that has an organized of transaction system for government bonds. Considering only trading in shares, BVC would be in fourth place after Ibovespa (Brazil), Santiago Stock Exchange (Chile), and the Mexican Stock Exchange (Mexico).

In 2011, with an initiative from the Santiago Exchange (Chile), the Colombia Exchange and the Lima Exchange (Peru) created the MILA (Mercado Integrado Latinoamericano), which integrates the three stock markets. This unification of markets intends to become the largest in terms of number of issuers, the second largest in market capitalization, and third in terms of trading volume after Brazil and Mexico.

A good case of a success story would be the Canadian-based Pacific Rubiales (PRE), an oil company that took a chance on Colombia and bought an underexplored oil field formerly owned by Exxon in 2007.5 Today it is the most productive oil pump with a production of 150,000 barrels a day and a revenue of US$3.4 billion in 2011.

This company is the second-largest company in Colombia, with over 4,000 direct employees. It has already expanded to countries like Peru and Guatemala. Although Pacific Rubiales is listed on the stock exchanges of Canada and Colombia, Pacific Rubiales seeks to increase its investor base through the Brazilian Stock Exchange to access capital in one of the world’s most promising economies.

Traditionally, Colombian politics have been bifurcated along liberal and conservative lines. Recently, alternative parties have entered the political landscape that provides more populist ideas of governance. Former Colombian president Alvaro Uribe Velez of the U party exemplifies these new elements. The U party supports the construction of a welfare state and recognizes the family as the foundation of society. It also recognizes and endorses globalization, with a strong emphasis on education, science and technology, and the opportunities of Colombia within the global market.

President Alvaro Uribe Velez’s eight-year administration was highlighted by his Democratic Security Policy, which aimed to eradicate militant activity and drug trafficking. In spite of being highly criticized by political opponents, the policy did decrease murder rates. Uribe also helped Colombia play a greater role in regional trade through the establishment of trade agreements and strengthening the alliance with the United States.

Juan Manuel Santos took the presidency in 2010 and in his first year has shown diplomatic abilities by expanding the relations with neighboring countries. Santos has established an economic policy that focuses on five target sectors, housing, infrastructure, mining, agriculture, and innovation, to provide stable growth of the Colombian economy. In order to generate funding for these investments, the government created the Private Initiative project, that allows individuals or corporations, partnerships, joint ventures, or any other form of association to submit proposals for public infrastructural works to a state agency, and if approved, finance the projects through private means and obtain a concession to generate revenues through tolls or taxes.

As a result of these combined efforts, the global Doing Business ranking for Colombia was forty-second6 out of 183 countries in 2012.

Taxes on Colombian capital gains are zero if the investor is selling no more than 10 percent of holdings within each fiscal year, otherwise capital gain taxes are 14 percent. Dividends in Colombia are taxed at a flat 33 percent rate with a credit exemption for taxes paid. Repatriation of funds from Colombian equities sold is also subject to a .4 percent financial transactions tax on after-tax funds.

Colombia’s economic growth is highly dependent on global demand for its commodities, particularly from two of the economies that are experiencing significant economic slowdowns, the United States and the European Union. This risk is further increased as China, which is also experiencing an economic slowdown, becomes an increasingly important trade partner.

Colombia still suffers from an emerging market type of economy; there are still many problems to be solved. According to the World Bank, 37.2 percent of the population are said to live below the poverty level, 53 percent of the land is held by 1.08 percent of owners, and investment in education and infrastructure is wanting. While the overall security situation in Colombia has improved immeasurably over the last decade, problems are still prevalent, as evidenced by an escalation of FARC attacks on oil infrastructure including pipelines last year. While these incidents should not act as a major drag on economic growth, particularly as the security situation in major cities has been stabilized, investors need to be conscious that any escalation in the activities of armed groups is difficult to predict and can seriously affect the economy particularly the oil and tourism industries. This would have a negative effect on foreign direct investment.

As the only country in South America with direct access to both the Pacific and Atlantic oceans, Colombia has the potential to facilitate trade along both coasts of the largest markets in the Western hemisphere (Canada, Mexico, and the United States). The recent signing of a free trade agreement (FTA) with the United States will help keep Colombia’s manufacturing sector regionally competitive. Although challenges remain, such as weak infrastructure and lingering security concerns, Colombia has placed itself on a trajectory toward sustained economic prosperity for the foreseeable future.

Overall, Colombia, despite media stereotypes of being a violent and unstable country, presents a far more attractive investment option than Brazil or Argentina. Brazil presents a rising political and investment risk being driven by a leftist economic agenda and reactive economic policies of the Rousseff government. Also, Brazil is experiencing a significant economic slowdown that will impact on investment returns. In comparison, Argentina has typically run on an unpredictable boom-and-bust economic cycle with increased investment risk. It is expected that in 2012 Colombia GDP growth rate will be between 5 percent and 5.5 percent, an estimate supported by all current indicators. This would almost double Brazil’s forecast rate of 3 percent, double the forecast 2.5 percent growth for the United States, and be higher than Argentina’s forecast 4.6 percent.

Michael Preiss

Mongolia Asset Management

Most investors know Mongolia in the context of Genghis Khan, and the startling history of how one extraordinary man from a remote corner of the world created an empire that led the world into the modern age.

Today, Mongolia is opening up to foreign investors and keen to share its wealth with those who are willing to engage in long-term strategic investment opportunities. Mongolia is one of the fastest growing economies in the world. The IMF estimates that the local economy will grow above 14 percent on average through 2012 to 2016. Today, an increasing number of global investors are becoming convinced that Mongolia will be the success story in Asia in the coming decade. This is a very exciting time for the country with its unparalleled economic growth potential.

Illiquidity and a small market size are often considered a key risk in frontier market investing. However, it is also important to remind ourselves that very often the reasons why the investment opportunity exists in the first place is because it is largely overlooked and under-researched and considered boring or too illiquid by many.

The Mongolian economy is set to expand rapidly as the mineral and commodity sector gathers momentum, fueling a domestic consumption boom.

Mongolia lines up an impressive pipeline of potential IPOs, including many state-owned enterprises, strategic mineral deposits, local industry leaders, and companies listed on foreign stock markets—a pipeline potentially worth US$45 billion in market capitalization. Government efforts to develop local capital markets are now taking place. The strategic partnership between MSE (Mongolia Stock Exchange) and LSE (London Stock Exchange) has successfully implemented a number of regulatory and system changes to bring the Mongolian capital market to international standards.

Mongolia is often considered a highly leveraged call option on the mining and China growth story. China, with over 1 billion people and consistently high GDP growth, is desperate for raw materials. The Tavan Tolgoi mine is considered by geologists to be the world’s largest untapped coal deposit, and Oyu Tolgoi (which means Turquoise Hill in Mongolian) is the world’s largest untapped gold and copper deposit.

The US$6 billion Oyu Tolgoi copper and gold project is on track to meet its initial production, targeted to commence in the third quarter of 2012. Installation of the two production lines in the concentrator and precommissioning work is progressing ahead of plan. The concentrator, which will have an initial capacity of 100,000 tons per day now is more than 80 percent complete. The first production line was scheduled to be completed during the third quarter, followed by completion of the second production line in the fourth quarter of 2012.

Mongolia is a landlocked country between Russia and the People’s Republic of China. It is 550 kilometers from the capital, Ulan Bator (Ulaanbaatar), to Beijing, and 700 kilometers to the port of Tianjin. It has the longest land border, with 12 border crossings with People’s Republic of China—4,600 kilometers; China’s border with Russia extends 4,300 kilometers. Mongolia has also a long land border with Russia of 3,500 kilometers; it is 235 kilometers from Ulan Bator to the center of the Siberian region, Irkutsk, and 3,000 km to Russia’s industrial Ural region . It is 2,000 kilometers from Ulan Bator to Seoul and 3,000 kilometers to Tokyo.

Mongolia’s strategic location is advantageous for resources exports to China compared, for example, with Kazakhstan and Australia.

With a massive land area of 1.5 million square kilometers, Mongolia is one of the top 20 largest countries of the world. It has 20 percent of Australia’s land area, yet a tiny open economy of US$8 billion, which is not even 1 percent of Australia’s. On the other hand, Mongolia has a stable, mature, and vibrant frontier democracy based on consensus building and a young, talented small population of 2.7 million with a lot of potential. Fifty-nine percent of the Mongolian population is below 30 years of age.

It is widely acknowledged that Mongolia is among the top 10 mineral - rich countries in the world. With only 17 percent of territory properly explored, it already has established in-ground value of top commodities in excess of US$3 trillion, compared to South Africa’s US$2.5 trillion.

According to the national statistics office of Mongolia, inflation was 10.8 percent nationwide in January 2012. According to the World Bank, inflation is forecast at 17 percent for 2012 (CPI). According to the IMF (November 2011), consumer prices (period average) are forecast to rise 18.7 percent in 2012.

According to the World Bank (October 2011), with budget expenditures increasing sharply in 2011 and 2012, overheating pressure will rise, feeding inflation that is already running at low double-digit levels. The 2012 budget envisages a 57 percent increase in wages and a 40 percent increase in transfers on the 2011 approved budget. There is therefore a substantial risk of a wage-price spiral, if higher inflation expectations become entrenched. Rising inflation, if not matched by preemptive tightening of interest rates, will push real interest rates close to zero or into negative territory, as happened in the run-up to the previous bust. High domestic inflation also causes the currency to appreciate in real terms, hurting the export sectors. Although the Bank of Mongolia has been quick to raise policy rates and reserve requirements, its efforts to control inflation will be more than offset if the extraordinarily large fiscal injections planned by the government materialize as planned.

According to the IMF (November 2011), the expansionary 2011 budget was a major source of the persistent inflationary pressures. The 2012 approved budget is still highly expansionary and continues to be a major source of inflationary pressure in 2012. Government spending, which was slated to grow by some 30 percent in the original budget, accounts for some two-thirds of the non-mineral economy and is thus a key determinant of aggregate demand. Any further increase in spending this year, therefore, is clearly not warranted. Additional spending this year would further overheat the economy, hurt the poor by driving up inflation, increase the vulnerability to a global commodity shock, and undermine credibility in fiscal policy and legal fiscal responsibility. Monetary policy, moreover, would not be able to offset a fiscal stimulus of this magnitude but would inevitably lead to a crowding out of private sector activity.

The consensus view is that although the 2012 budget is still highly expansionary, more realistic projections in the 2012 budget are a reflection of a political will to restrain inflation that is more widely perceived as a greater macro risk in case of prolonged fiscal expansion. 2012 is an election year and therefore there would be acceleration of politically motivated actions such as cash handouts. End result inflation in 2012 would be dependent on fiscal intentions and political commitments.

We believe that the Mongolian stock market and local currency assets in the fastest growing economy in the world are hidden jewels of frontier market investing.

The stock market in Mongolia was established in 1991 when the collapse of the Soviet Union compelled Mongolia to switch from a communist to a capitalist economy and democracy. Mongolia decided to privatize state assets through the creation of a stock market.

Since then the local capital market has developed and today is again at a major turning point as the country becomes the fastest-growing economy in the world.

MSE (Mongolia Stock Exchange) was the best-performing stock market in the world in 2010 with over 130 percent growth and despite a downward pull, Mongolia still managed to be the second-best–performing stock market in the world in 2011 with a 47 percent return.

We expect that the MSE will continue its multi-year bull market trend, as market liquidity improves and more and more Mongolian companies seek IPOs on the local market.

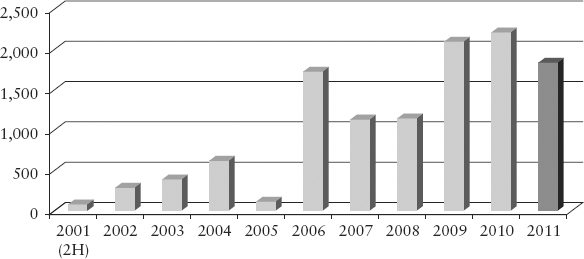

The MSE will likely see consistent success in coming years. The Mongolian stock market might not offer the best emerging market returns every year as it did in 2010, but investors worldwide have taken notice of the compelling long-term investment story (see Figure 12.5).

FIGURE 12.5 Mongolia Top 20, 2010 to 2012 First Quarter—Quarterly Index Levels

Source: Mongolia Stock Exchange.

We expect market cap and daily equity average turnover to substantially increase in 2012, however gradually. The strategic partnership between the MSE and the London Stock Exchange (LSE) to modernize the MSE and bring world-class standards by introducing a state-of-the-art trading system to the local market is revolutionizing the local capital market. The LSE has a three-year contract to actively manage the MSE.

The Mongolia Financial Regulatory Commission (FRC) is working on introducing new securities laws as well as an investment fund law.

We believe the downside risk in Mongolia equities is limited, as true profitability of Mongolian companies is still understated and the economy expands at a rapid pace. The balance sheet assets of many locally listed Mongolian companies are still undervalued or the book value of assets is much lower than their market value or replacement cost.

We expect an additional number of new share offerings and IPOs in 2012 as the Mongolian government is privatizing state-owned enterprises (SOEs) in mining, mineral processing, power generation and distribution, construction materials, telecom, and transportation.

The tögrög or tugrik (code: MNT) is the official currency of Mongolia. It is a resource and commodity currency similar to the Australian dollar but with much higher yield and real interest rate.

MNT was the second best performing currency in the world in 2010, appreciating 13 percent against the US dollar. According to the Bank of Mongolia, mining operations were in their initial stages, and demand for US dollars was low.

However, in 2011 the economy grew by 17 percent and the Mongolian currency depreciated by 11.4 percent against the US dollar. According to the Bank of Mongolia, mining operations were under heavy development and the demand for US dollars increased rapidly, both from the public and the government. Although the US currency inflow was the same, its outflow had increased causing the drop in the MNT rate.

In other words, the US$/MNT rate depends on the way Mongolia spends its income. According to the IMF, extraordinary growth in spending could lead to overheating the economy, high inflation, rapid growth in imports due to excessive domestic demand, and macroeconomic uncertainty, all of which are influencing the exchange rate. External considerations and domestic Mongolian factors tend to exert downward pressure on Mongolia’s currency.

According to the World Bank, the trend for the year suggests that high domestic inflation is mirrored in the weakening of the currency. Rising global risk aversion and declining commodity prices are additional factors contributing to the depreciation, as has occurred in other mineral-rich emerging economies.

According to the Bank of Mongolia, the main indicators of the balance of payments of 2011 are:

After the massive increase in exports due to the production at Oyu Tolgoi comes to an end in 2014, it is expected that the MNT will appreciate against the US dollar and other major currencies. In the meantime, one of the highest interest rates in the world means that investors can compound capital at an attractive rate.

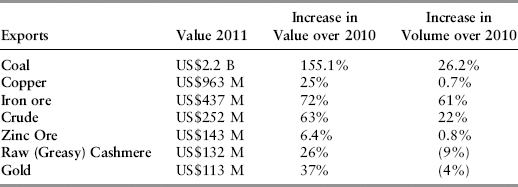

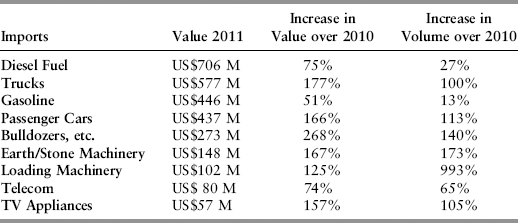

According to the National Statistics Office of Mongolia and the preliminary results for 2011, Mongolia traded with 127 countries and external trade turnover reached US$11.3 billion; exports amounted to US$4.8 billion and imports to US$6.5 billion. External trade increased overall by US$5.2 billion or 85 percent compared to 2010, with imports up by 104 percent and exports up by 64 percent.

Mongolia benefited from favorable commodity prices in 2011 for virtually all its export commodities such as coal, copper, iron ore, crude, (greasy) cashmere, zinc, and gold. At the same time, imports are rising due to mining, infrastructure, construction, and private consumption; terms of trade are getting more expensive.

Trade statistics (Tables 12.1 and 12.2) the rapidly growing importance of the primary sector as well as commensurate growth in consumer spending.

TABLE 12.1 Republic of Mongolia: Main Exports

Source: National Statistics, Mongolia Asset Management Analyses.

TABLE 12.2 Republic of Mongolia: Main Imports

Source: National Statistics, Mongolia Asset Management.

Banking is the life blood of any economy, especially for a fast-growing market like Mongolia. As the vast natural resource wealth filters through the general economy, it will create more government spending, more job opportunities, better infrastructure, and greater demand for loans and more sophisticated financial services.

There are 14 banks in Mongolia and the sector is growing rapidly. The key players are Khan Bank of Mongolia, Golomt Bank, Trade Development Bank of Mongolia, and Xac Banks. High economic growth and the multiplier effect of the natural resources boom in the country are creating a host of opportunities for banks in Mongolia.

According to the World Bank, lending is expanding at a healthy pace in order to deploy the strong influx of deposits. According to Bank of Mongolia (January 2012), total savings increased in 2011 by 41 percent to reach MNT3.89 trillion. Seventy-five percent of savings are MNT and 25 percent are in foreign currency.

According to the Bank of Mongolia, the weighted average interest of securities of the Central Bank increased by 3.3 percentage points to reach 14.25 percent. Weighted average interest for MNT loans declined 2.4 points to 15.5 percent and for foreign currency loans interest declined 0.5 points to 12.1 percent. Weighted average interest on MNT savings declined by 0.2 points to 10.5 percent and for foreign currency savings interest increased by 0.5 points to 4.5 percent.

According to the National Statistics Office of Mongolia (January 2012):

Mongolia is one of the richest countries in the world in terms of natural resources and is now making rapid progress with respect to exploiting these resources. The country is known around the world for its two major mining projects, OT (Oyu Tolgoi) and TT (Tavan Tolgoi).

OT appears to be on track and close to completing its funding. The latest developments include: Facilities required for the first ore production in mid-2012 remain on schedule and commercial production is expected to commence in the first half of 2013. The stringing of power cables was expected to commence in spring 2012. Bilateral agreements were expected in 2012 to ensure that imported power would be available at the site by the third quarter. Oyu Tolgoi LLC was finalizing a study on alternative power-generation arrangements to be implemented in the event that imported power would not be available by the third quarter of 2012.

Ivanhoe Mines, Rio Tinto, and a core lending group are working together to finalize an approximate US$4.0 billion project-finance facility for the Oyu Tolgoi Project, with the objective of signing the loan documentation in 2012.

The Tavan Tolgoi (TT) mine is to export 3 million metric tons (Mt) coal in 2012. 2012 prices to the buyer, Chalco, are adjusted according to an agreed index. The operating company (ETT) will build a two-lane paved highway beside the MMC highway, with construction to start in mid-2013. If there is a successful IPO for ETT, investments will maintain projects and growth in 2012 and 2013. A south railroad will be started at the same time as the east railroad to the Sainshand Industrial Hub.

The South Gobi region coal exports including value-added (washed) could reach a record in 2012 and we estimate volumes in a range of 25 to 30 Mt with a value of US$2.25–2.75 billion. Although there is a lot of progress with coal highways, industry consensus view is that infrastructure capacity is still a constraint to export growth. With softening prices the total value of coal exports is unlikely to increase as much as the new tonnage.

We expect record iron ore exports in the range of 8 Mt and a value of around US$500 million, softening commodity prices in 2012. We estimate the volume of copper exports should remain virtually the same as in 2012 with a value of around US$1 billion.

Mongolia is a stable, mature, and vibrant frontier democracy based on consensus building: It is praised as model democracy by the United States, has more than 50 TV stations, is flourishing with robust media, and is a civil society.

The stable political system of Mongolia is its greatest advantage and encouragement for investors. Political risk premium overall is decreasing; however, 2012 is an election year. Overall, progress is there, but it is sometimes slow and riddled with challenges as the country learns to deal with its unprecedented natural resource wealth and economic boom. Patience and long-term commitment are required.

Mongolia has successfully managed a double transition—from an authoritarian state to a democracy, as well as from a centralized to a market economy. The political reform and democratization in Mongolia have been remarkably swift, smooth, and thorough. After almost 70 years of socialist rule in virtual isolation from the outside world (except for COMECON countries), Mongolia stands out as one of the front-runners in political and institutional reforms. An open and democratic society has been established and is being consolidated at all levels.

There have been positive developments in the level of governance in Mongolia. The overall drive toward democracy and a market economy is undoubtedly a national commitment and an irreversible process. Some results have been achieved in strengthening the institutions and mechanisms of government over the past few years and in putting into place mechanisms for redressing mismanagement and inefficiency.

Below the radar of most investors except multilaterals and those dealing with Least Developed Countries (LDC, a United Nations designation), the economy of Haiti in the Caribbean has many of the hallmarks of potential success looking extremely far out, possibly half a generation. This country truly represents the ultimate frontier.

There are three reasons to look at this country as an example of where a least developed economy could be in one to three decades:

The country was devastated by an earthquake in 2010 and has the opportunity to rebuild itself with very substantial debt relief and financial aid from multilaterals and the benefit of insight gained from observing the experience of comparable economies.

A democratic base is in place. The current president, Michel Martelly, has been quoted as saying that “everything is a priority in Haiti:10 modernizing the economy, providing access to free education, strengthening the agricultural sector, and moving earthquake victims out of tents by jump-starting reconstruction.11 as well as strengthening the rule of law and combating corruption.” President Martelly announced, “starting May 14, Haiti will change. The state of law, like it or not, will become a reality. No person, no institution, will be above justice.”

Haiti could emerge victorious from the disaster of the earthquake and start a modern and rapidly developing economy with a multitude of advantages over other Caribbean markets that already have demonstrated a capability to generate prosperity, stability, and economic success. This is the one after next opportunity for investors, nationals, and foreigners alike.

Haiti is the second oldest republic in the Western Hemisphere, after the United States. It shares the island of Hispaniola with the Dominican Republic. Covering an area of 27,750 square kilometers, the 2011 population was estimated at 9.7 million.

10.4 percent of the population is employed by industry and 28 percent by the commerce, tourism, and transportation sectors. The largest segment of the population works in the agricultural sector and two-thirds of the population is dependent on subsistence farming. The World Bank categorizes Haiti as a low-income, chronic food deficit country, which means it is able to produce less than half of its food needs.13 Haiti was categorized as a Least Developed Country (LDC) by the United Nations in 1971,14 the “poorest and weakest segment” of the international community. Such designated countries enjoy tariff-free exports of certain products to most developed nations, including the United States and many European countries.

The 2010 earthquake, with its epicenter close to the capital, Port-au-Prince, caused damage in value greater than the country’s total GDP for 2009. The government reported more than 300,000 homes destroyed or damaged. More than 1,300 educational establishments and over 50 hospitals and health centers became unusable, the main port became partly inoperable and many roads were left unstable, and government buildings were destroyed.15

Moreover, the international community has a less than favorable assessment of the current state of affairs. The 2012 Heritage Report states critically: “Overall progress in reforming the Haitian economy has been modest. The effectiveness of government spending has been severely undermined by political volatility that continues to sap the foundations of an already weak rule of law. Reforms to improve the business and investment climates have had little effect in light of Haiti’s pervasive corruption and inefficient judicial framework. Limited efforts to liberalize trade have had little impact, and bureaucracy and red tape deter investment. Despite a UN Stability Mission and a better-trained and equipped national police force, disorder is still easily sparked by paid gangs. Unemployment is very high, most economic activity is informal, and emigrants’ remittances have yet to recover fully from the 2009 global economic downturn. Corruption, gang violence, drug trafficking, and organized crime are pervasive.”16

Small improvements in reducing corruption and continued moderation of inflation offer signs of hope. It is hard to imagine a less favorable starting position. This is evidenced by the rise in the ranking of the Heritage Freedom Index. Haiti is ranked 142nd globally in terms of economic freedom with a score of just above 50 percent (still mostly not free) and about 20 percent below the world and regional averages. Still, this ranks Haiti ahead of Russia, one of the BRIC countries, and countries like Argentina, Venezuela, and the Ukraine in terms of economic freedom.

The estimated cost for long-term reconstruction in Haiti is US$11.5 billion. Immediately following the earthquake, the international community pledged US$9.9 billion over the next decade for relief, recovery, and development in addition to technical assistance and other non-financial resources.17 The United States is Haiti’s largest sovereign donor18 and the Inter-American Development Bank (IADB) is its largest multilateral donor.19

After the earthquake, Haiti’s government updated its comprehensive strategy, with a plan to raise medium-term growth and reduce poverty, with a focus on four main areas:

The economic outlook is positive. For the first time in history, the state budget of Haiti exceeded HTG 100 billion (approx. US$2.5 billion), reaching a total of US$2.65 billion for the 2010–2011 fiscal year.21 Government revenue is heavily dependent on prevailing taxes that apply to most economic activities. Yet government revenues are low in comparison to expenditure needs and comparable economies.

The macroeconomic situation has also improved and prospects have been bolstered by debt forgiveness of countries (United States and Venezuela) and multilaterals (IADB, IMF, WB). Debt forgiveness, remittances, and global aid have allowed Haiti’s central bank to build reserves and stabilize the currency. However, many believe recovery is being hampered by the delays in disbursement of pledged donations. Only one-fourth of the total US$5.5 billion pledged by the international community for 2010–2011 has been disbursed.

Haiti is a market based economy with ample low-cost labor and a new pro-business government. Haiti’s 2010 GDP was US$6.6 billion and its corresponding purchasing power parity (PPP) GDP was US$11.48 billion. Per capita GDP during the same period was approximately US$673 with PPP GDP at approximately US$1,164 per capita. Haiti’s GDP growth in 2008 and 2009 had been 0.8 percent and 2.9 percent, respectively, after which it fell to -5 percent in FY 2010 due to the earthquake. However, the IMF expects GDP growth of 8.6 percent in 2011 and 8.8 percent in 2012.22

Inflation in Haiti is comparatively moderate and primarily attributable to a reduction in goods available, the increase in transportation costs due to global fuel prices, and significant inflows of external aid.23 While inflation was forecast to rise to 8.5 percent in 2010, it was contained at 4.7 percent.24 Nevertheless, the IMF expected inflation to peak at 9 percent in 2011, but then fall to 6.5 percent in 2012.

Trade is only emerging. The United States is Haiti’s largest trading partner, accounting for 70 percent of Haiti’s exports and 50 percent of its imports.

The banking sector in Haiti comprises eight registered banks, with 66 percent of all bank branches located in Port-au-Prince. Many Haitians do not have access to the formal banking system—micro finance does exist—because they are either too poor or do not live in or near Port-au-Prince. The average outstanding loan is US$12,700 and extension of credit is limited to a small number of firms and individuals. Banks currently lend to only 55,000 borrowers with a total loan portfolio of US$800 million. In 2011, interest rates on loans were approximately 9 percent for US$ and 14 percent for HTG lending while savings rates are around 1 percent.

Agriculture accounts for approximately 25 percent of Haiti’s GDP and 50 percent of employment, comprising 72 percent of rural employment.25 Haiti produces a variety of crops including rice, sugar, cacao, coffee, sorghum, mangoes, hot peppers, pineapples, avocados, and sweet bananas.

Growth in the agricultural sector is limited by overuse of soil and poor irrigation techniques. The wide range of environments in terms of altitude, soil type, and climate allows for a wide variety of crops to be grown in Haiti.26

Coffee and cocoa are two of the dominant cash crops in Haiti. USAID estimates coffee production to be annually around 400,000 bags on 40,000 hectares of land.27 Approximately 150,000 to 200,000 farm families depend on coffee.28 Only 10 percent of the production is marketed through formal channels. Coffee used to be a major export item (up to US$70 million) however exports are now down to less than US$5 million.

The cocoa value chain is supported by approximately 20,000 micro-producers. Total national production was estimated at 4,450 metric tons in 2008, with exports reaching approximately 3,800 metric tons (approximately US$10 million).

The government acknowledges the need to invest in modernizing farming equipment and techniques as well as intrastate support, such as better roads, improved irrigation, and storage units to prevent waste due to spoilage. Improving the efficiency of the sector could dramatically increase production and raise export volume. Exotic fruits and vegetables are promising sectors for Haiti, given their easy access to US consumers. Also, obtaining organic and free trade certification would be a way for Haitian products to gain access to foreign markets.29

The food processing industry in Haiti is underdeveloped. Currently, the most developed areas in the food processing industry are for traditional crops: sugar, cacao, and coffee. In addition to land-based crops, aquaculture has good prospects. Several international aid organizations have laid the foundation for a fish farming industry. Haiti also has access to open ocean for sea farming, with 1,100 miles of coastline and waters that extend 200 miles out to sea in an exclusive economic zone.

The manufacturing sector contributed only 7.6 percent to GDP in 2010.30 The garment industry is the largest manufacturing sector, comprising 80 percent of Haitian exports to the United States and employing over 28,000 people.31 Haiti was once a reliable supplier of assembled goods to the US market and employed as many as 100,000 workers during its peak production period,32 which lasted from the 1960s through 1986.33

The biggest boost to the Haitian garment industry has come from the United States granting increased access to its market through the 2000 Caribbean Basin Trade Partnership Act (CBTPA) reforms, the 2006 US Congress HOPE Act, and the 2008 HOPE II Act. Under CBTPA, Haitian garment exports to the United States increased from $250 million in 2000 to $450 million in 2006. The industry continues to grow at more than 20 percent annually, with 2010 garment and apparel exports valued at more than US$550 million.

Only 12 percent of Haiti has access to electricity and 80 percent of electricity demand comes from Port-au-Prince. Most of the energy is produced by light fuel oil at a cost of between US$0.22 and US$0.26 per kWh when crude oil is trading between US$60 and US$80 per barrel. Demand far outstrips supply, but electricity generation is projected to increase fivefold until 2028.34

Tourism has long been a priority but the 2010 earthquake caused widespread damage. The total contribution of tourism to employment is forecast to rise by 3.6 percent per annum from 182,000 jobs in 2011. The total contribution of tourism to GDP is equally projected to rise noticeably from 6.0 percent of GDP in 2011.35 Plans include rehabilitating the Port-au-Prince airport and adding two international airports in Cap Haïtien and Les Cayes.

Although Haiti’s telecommunications system is considered among the least developed in Latin America and the Caribbean, mobile density reached 40 per 100 persons in 2009, or 3.6 million cellular phones. Landline use is far more limited. Yet, as of 2009, there were an estimated one million Internet users in the country ranking Haiti 99th in Internet penetration in the world36

In a 2001 assessment of the investment climate in Haiti, the Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development (OECD) identified political instability and physical security as the primary concerns for potential investors considering doing business in Haiti. The same report pointed out the advantages of investing in Haiti, which include its proximity to the United States and a large potential labor force.37

In 2007, the Haitian government affirmed Foreign Direct Investment (FDI) as a central pillar of its economic revitalization plan. Three key initiatives were enacted:

All initiatives have created the right objectives for the first stage of a possible investment destination. Once implemented, they could form the base for significant progress. Stellar economic performances are not unheard of. This year Mauritius rose from 72nd to 8th in the world in terms of economic freedom (The Heritage Foundation).

Haiti has several overlapping laws and decrees that govern, administer and regulate the establishment, operation, and governance of free zones and industrial parks. Both provide for duty- and VAT-free imports of equipment and raw materials, as well as similar exemptions from payroll and corporate income taxes for park/free zone operators and tenants.

Restrictions on foreign investment remain. Haitian law stipulates that any foreign investment with a potential impact on the country’s economy is subject to presidential approval. Haiti also has more explicit restrictions in banking where foreign ownership is capped at 49 percent. The domestic air transportation sector is closed to foreign equity ownership. Seaports and airports are controlled by government monopolies. Other sensitive sectors include mining, energy and gas, electricity, and water. However, the private sector is making inroads in mining and energy production.

Foreign ownership of land is allowed, but restricted to one property for immediate operational needs. Foreign ownership of more than one property requires approval from the Ministry of Justice. Property rights of foreigners are limited to 1.29 hectares in urban areas and 6.45 hectares in rural areas.38 Foreign companies may lease or buy land from private owners or from the state. Lease contracts can offer the lessee the right to sublease, mortgage, or subdivide the land.

All Haitian companies must have at least three shareholders and three board members; one member of each group is required to be a Haitian national. The minimum requirement for capital is the same for both domestic and foreign-owned companies.

Haiti is a member of the Caribbean Community and Common Market (CARICOM) and applies common external tariffs. Liberalization measures include eliminating export duties, simplifying and lowering tariffs, and removing quantitative restrictions. According to the World Bank, Haiti’s simple average most favored nation (MFN) tariff has remained at 2.8 percent, which is lower than the average low-income country. Imported goods bear a heavier effective tax burden of 6.9 percent. A 2 percent tax on import duties is also imposed, along with a turnover tax of 10 percent and excise duty on both imports and domestic products.39

Haiti does not have free trade agreements, but rather framework agreements drawn up according to the most-favored-nation principle with multiple countries and through the CARICOM agreement.40 Haiti is a beneficiary of the WTO General System of Preferences; the Caribbean Basin Initiative (CBI) with duty-free access to the US market for many products; the Canadian Programs for Commonwealth Caribbean Trade; and the Investment and Industrial Cooperation (CARIBCAN) with preferential treatment for exports to Canada.

Haiti adopted the French civil law system. French doctrine and jurisprudence guide interpretation of the law.41 Haiti is a contracting state to the 1966 Convention on the Settlement of Investment Disputes Between States and Nationals of Other States (ICSID or the Washington Convention) and the 1958 UN Convention on the Recognition and Enforcement of Foreign Arbitration Awards.42 Haiti abides by regional arbitration mechanisms under its agreement with CARICOM.43

All commercial matters are subject to arbitration, except for disputes involving the state, government entities, minors, and incompetent adults. The Chambre de Conciliation et d’Arbitrage (CCAH) it is not yet fully operational but on its way. Arbitration agreements must be concluded in writing and proceedings must be conducted in French.

Haiti has a long history of protecting foreign investment. The 1987 constitution reinforced protections on foreign investment. In 2002, the Haitian parliament passed an investment code that explicitly recognizes the rights of foreign investors, such as in Article 11 of the Investment Code: “No other authorization, license or permit, which is not required of Haitian investors, is applicable to foreign investors.” Foreign investors pay taxes, duties, and levies according to the schedules and regulations that are applicable to Haitian investors. The right to real estate is guaranteed to foreign investors for the needs of their enterprise. Foreign investors enjoy free transfer of interest, dividends, profits, and other revenues stemming from their investments.

The judicial system as a whole is still weak and needs substantial revamping and strengthening. The precariousness of land titles, in the absence of a clear official registry, can also be a major constraint.

The key to success for Haiti is proper governance, adequate infrastructure, and institutions to give the ready and young work force a mandate to develop. In the past, Haiti was one of the major exporters to the United States and the proximity to the largest consumer market in the world represents a major opportunity to turn around the fortunes of the country. Haiti only serves as an example of an economy largely ignored but with many of the attributes to become a successful investment destination. We should not ignore economies in the long term just because they do not have the right characteristics at this point in time; they may well be part of a winning proposition in the years or decades to come.

Despite its tumultuous past, Colombia is strategically located and poised for strong economic growth in the coming decade and could emerge as a leading economy in South America. Colombia’s government has begun to make inroads toward stemming violence, which has helped increase domestic production, consumption, and foreign investment, while decreasing unemployment. In addition, Colombia is now better equipped to capitalize on its natural resource deposits, which include oil and natural gas that will fuel domestic growth.

The Mongolia Stock Exchange, small and narrow as it stands today, has outperformed most other markets driven by attractive resource stocks. Far-sighted investors realize that in a world with too much debt and structurally weak Western economies, investment in resource rich economies is one of the best macro trades.

Consider Haiti as a market without a stock exchange and without any decent capital market. This would be of no interest to investors except multilaterals and private equity investors. Now consider Haiti as a mid-sized multinational corporation that will receive an equity capital injection one and half times the size of its business. That would be an investment proposition.

1. “Seeking Alpha,” seekingalpha.com (July 22, 2011).

2. “El Cerrejon,” www.cerrejon.com.

3. “Zona franca Bogota,” www.zonafrancabogota.com/en/.

4. Proexport, www.proexport.com.

5. “Pacific Rubiales,” www.pacificrubiales.com/corporate/company-history.html.

6. “Doing Business,” www.doingbusiness.org/.

7. CIA, The World Factbook: Haiti.

8. Ibid.

9. World Bank, “Haiti: Recent Progress in Economic Governance Reforms,” siteresources.worldbank.org/INTHAITI/.../Governance_reforms_Haiti.pdf.

10. Georgianne Nienaber, “Haiti’s Michel Martelly: The Election, Fraud, and the Future,” La Progressive (December 8, 2010).

11. Moni Basu, “Haiti’s New Leader Makes Rounds in Washington, Vows Transparency,” CNN World (April 21, 2011).

12. News 24, “Haiti’s Martelly Vows ‘Rule of Law,’” (April 6, 2011).

13. Food and Agriculture Organization (FAO) of the United Nations, Low-Income Food-Deficit Countries (LIFDC)—List for 2011.

14. United Nations, Handbook on the Least Developed Country Category: Inclusion, Graduation and Special Support Measures (November 2008).

15. Government of Haiti. Haiti Earthquake PDNA.

16. 2012 Index of Economic Freedom, The Heritage Foundation and the Wall Street Journal (2012).

17. United Nations, News & Media: UN/HAITI DONORS 3.

18. US Department of State, Background Note: Haiti.

19. Inter-American Development Bank, History of the IDB in Haiti.

20. Government of Haiti, Action Plan for the National Recovery and Development of Haiti (March 2010).

21. Haiti Libre, Haiti—Economy: “The Budget of Haiti 2010–2011, Passes 100 Billion Gourdes” (December 14, 2010).

22. International Monetary Fund, World Economic Outlook Database (April 2011).

23. Economist Intelligence Unit, Haiti: Country Report (February 2011).

24. World Bank, “One Year Later: World Bank Group Support for Haiti’s Recovery” (January 2011).

25. Government of Haiti. Haiti Earthquake PDNA: Assessment of damage, losses, general and sectoral needs (March 2010).

26. Government of Haiti, Action Plan for the National Recovery and Development of Haiti (March 2010).

27. USAID, “The Haitian Coffee Market Chain.”

28. Fernando Rodriguez et al., Assessment of Haitian Coffee Value Chain, Catholic Relief Services.

29. World Economic Forum, Private Sector Development in Haiti: Opportunities for Investment, Job Creation and Growth, 2011.

30. J. F. Hornbeck, “The Haitian Economy and the Hope Act,” Congressional Research Service (June 24, 2010).

31. International Trade Administration, “Haiti Uses a Bit of MAGIC to Energize Their Textile Industry.”

32. Embassy of the United States in Port-au-Prince, Fact Sheet: North Industrial Park (January 11, 2011).

33. J. F. Hornbeck, “The Haitian Economy and the Hope Act,” Congressional Research Service (June 24, 2010).

34. Nexant Caribbean Regional Electricity Generation, Interconnection, and Fuels Supply Strategy Final Report (March 2010); submitted to the World Bank.

35. World Travel and Tourism Council, “Haiti: The Economic Impact of Travel and Tourism (2011).

36. CIA, The World Factbook.

37. Martha N. Kelley, “Assessing the Investment Climate in Haiti: Policy Challenges,” Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development (2001).

38. US Department of State. Background Note: Haiti, Bureau of Western Hemisphere Affairs (August 10, 2011).

39. World Bank, “Haiti: Trade Brief” (2008).

40. Caribbean Export Development Agency, “Doing Business With Haiti” (May 2007).

41. Marisol Florén-Romero, “Researching Haitian Law,” New York University GlobaLex (May/June 2008).

42. United Nations Commission on International Trade Law, “About UNCITRAL.”

43. Martha N. Kelley, “Assessing the Investment Climate in Haiti: Policy Challenges,” Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development (2001).