Three neighboring economies in Southeast Asia have recently started or are upgrading their stock markets. While they each have only one or two stocks listed, they have the potential to expand and become attractive investment destination candidates down the road.

For private equity investors they are rising in terms of interest and offer the promise of the few last and large frontier markets heretofore not considered.

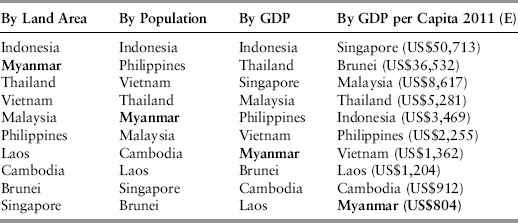

In recent times, few emerging countries have attracted more media interest than Myanmar (Burma). After some troubled history throughout the second half of the twentieth century and a general isolation from the world, the government embarked on a set of significant political reforms that rekindled foreign interest and support. The continued path of reform is leading to a widely expected relaxation of sanctions imposed by the United States and the EU. The country has a population of some 58 million, abundant natural resources, a compound GDP growth rate of around 10 percent over the period 2001 to 2011(E),1 and is surrounded by generally booming neighbors and fellow ASEAN members. Within ASEAN, Myanmar is the fastest-growing, second-largest, and least-developed major economy by GDP per capita (see Table 13.1). However, prior to the military coup in 1962, it was the richest country in Asia, with a strong legal system, leading training and educational systems, and a high proficiency in English.2

TABLE 13.1 Myanmar within ASEAN

Source: UBS research, IMF estimates for 2011, author’s analyses.

Given its size, resource endowment, and history, Myanmar is the last large frontier market of Asia that could become of interest to global capital flows.

The economy is dominated by the primary sectors: agriculture and resource extraction, which also account for the lion’s share of exports.3 Manufacturing has increased, primarily in state-owned enterprises, but remains of secondary importance, as do services.

Externally estimated composition of GDP would indicate that about 51 percent of GDP is agriculture, about 37 percent services, and about 9 percent industry.4 The labor force is predominantly employed in agriculture (~64 percent) which may explain the high labor participation rate: 83 to 86 percent male and 63 to 69 percent female.5 Primary school enrollment is 100 percent (secondary school enrollment is 24 percent) and consequently the adult literacy rate is 81 to 85 percent.

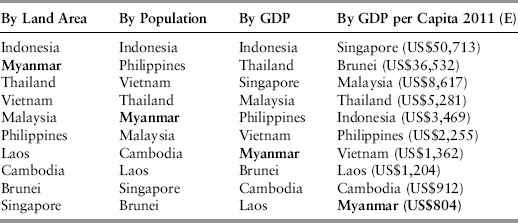

External trade in 2010/2011 (see Figure 13.1), the combined value of exports and imports, amounted to around 32 to 35 percent of GDP, somewhat ahead of other least developed economies (LDCs). Average trade to GDP ratio for LDCs in 2009 amounted to 26 percent; for the world it amounted to 27 percent.6

FIGURE 13.1 Myanmar External Trade, April 2007 to December 2011

Source: Central Statistical Office, Myanmar, December 2011, author’s analyses.

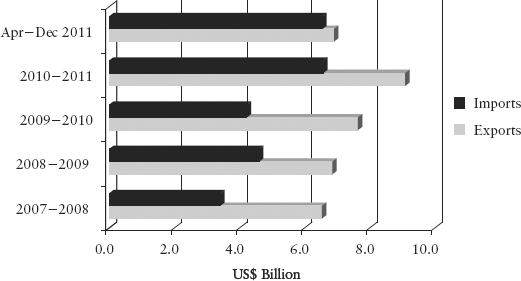

International sanctions are a main constraint for Myanmar as is the low development of its industries. Due to sanctions from the United States and the European Union, the major trading partners for exports are Thailand, China (including Hong Kong), and India(see Figure 13.2).

FIGURE 13.2 Myanmar Major Export Destinations, April 2007 to December 2011

Source: Central Statistical Office, Myanmar, December 2011, author’s analyses.

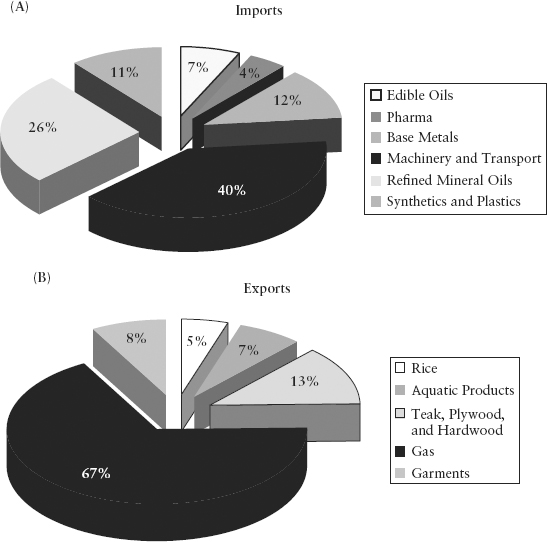

Gas, teak, plywood, and hardwood as well as aquatic products are the major export items; garments are the major manufactured export (see Figure 13.3). Production of rubies and sapphires amounted to 6.5 million and 4.0 million carats respectively over the same period. Jade extraction resulted in 157.5 million metric tons between 2007 and 2011. These and other precious stones are presumably exported but not disclosed separately. They are included in the category “others” that accounts for over US$12 billion of exports for the period.

FIGURE 13.3 Myanmar Major Imports and Exports, April 2007 to December 2011

Source: Central Statistical Office, Myanmar, December 2011, author’s analyses.

Agricultural produce is equally growing in export importance. Pulses (legumes used for food and/or animal feed) and rice are the major export items that are rising in importance.

Not surprisingly, machinery and transport equipment and refined mineral oils are the major imports. They go to support the primary industries.

In absolute value, external trade is not significant. However, the potential needs to be considered. Despite the limitations of the economy due to its political system and international sanctions, Myanmar has already carved out an appreciable position in global terms. While still a least developed economy and in the bottom 10 percent of economies by GDP per capita, it excels in several areas of economic activity (see Table 13.2).

TABLE 13.2 Global Share and Rank of Key Myanmar Products and Commodities

Source: Central Statistical Office, Myanmar, December 2011, FAO, WTO, UN statistics, UNIDO, World Bank, BP, industry news, Haik Zarian, author’s analyses.

| Product/Commodity | Share of Global Value | Global Position |

| Population | 0.8% | Top 25 |

| GDP nom | 0.1% | 70–75 |

| GDP PPP | 0.1% | 73 |

| GDP/PPP/ per capita | n/a | 163 |

| Teak Wood | 60–80% | Top |

| Rubies | 30%+ (E) | Top 2 |

| Sapphires | 10%+ (E) | Top 6 |

| Fuel Wood | 2.1% | Top 10 |

| Aquatic Products (captured) | 1.3% | Top 15 |

| Garments | 0.2–0.5% | Top 30 |

| Natural Gas Production | 0.4% | Top 35 |

| Natural Gas Reserves | 0.2% | Top 40 |

Teak cultivation and production, although not critical in a global context, is a case in point that highlights the economic potential based on the history of the country. Myanmar established plantations to produce teak in 1856 and those early foresters had the foresight to make it possible for future generations to reap the financial benefits of the plantations on a sustainable basis.7 Today, the country is the world’s most important teak producer and trader.

Such pockets of strength and the abundant natural resources attracted foreign direct investment despite the restrictions placed on the country. Most of the investment went into power generation and oil & gas exploration, followed by mining. Relatively small investments (still above US$100M over five years)—are made in agriculture and smaller in industries (see Figure 13.4).

FIGURE 13.4 Foreign Direct Investment in Myanmar, April 2007 to December 2011

Source: Central Statistical Office, Myanmar, December 2011, author’s analyses.

The country of origin of foreign direct investment over the past five years is not dissimilar to the trade pattern. According to national statistics, China was the largest foreign investor with some US$13.5 billion, followed by Hong Kong with US$5.8 billion, Thailand with US$3.0 billion, and Korea with US$2.7 billion.

A stock market small in nature was established in Myanmar before the great depression of 1930s in the form of Yangon Stock Exchange, but trading was limited. In fact, there were only seven members, all of which were European firms. Trading took place within an informal OTC framework. A leading European firm issued quotations of prices, which were published by their newspaper. A majority of the stockholders were Indians. There were no Myanmar companies listed in that fledgling market.

In the late 1950s, with a view to encouraging private sector development, the government formed nine joint venture corporations with the private sector. Shares of those joint venture corporations were traded as preferred stock in an unofficial OTC market. This market was closed when nationalization of economic entities took place as the centrally planned system was adopted in Myanmar, in 1962.8

A small stock market was reopened in 1996 (a Daiwa Securities JV) and in 2006, a government committee drafted a road map for the development of capital markets in Myanmar with a view to an ASEAN interlinked stock market. In 2008, the government set up a Capital Market Development Committee. Most of the work included in the first phase has already been implemented successfully, with the second phase planned for 2010 to 2012 and phase III from 2012 to 2015.

At present, two stocks, Myanmar Citizens Bank and Forest Products JV Corp., both majority owned by government, are thinly traded over the counter, as are government treasury bonds. The stocks provide attractive dividend yields of about 25 percent and the bonds do equally well. There is a shortage of supply and no liquidity.

The Tokyo Stock Exchange with Daiwa Securities recently announced a partnership with the Myanmar Securities Exchange Centre Co. and the Central Bank. The aim is to create a full-fledged stock exchange by 2015 using the technology and trading platform of the Tokyo Stock Exchange.9 Competition comes from the Korean Exchange, equally keen to open a new exchange/rekindle the exchange in Myanmar. The Korean Exchange already operates the Lao and Cambodia exchanges and the potential of these economies for an attractive stock market is considerable.

The general characteristics of the legal system are dominated by the British common law system established during the period 1886 to 1948 and these laws continue to be applied, such as the Contracts Act of 1872 as well as related precedent.10

The current Foreign Investment Law of 1988—the revised Foreign Investment Law is under debate by the National Assembly—allows foreign investment in many sectors and provides a tax holiday, export concessions, and depreciation allowances/preferential accounting rules as well customs and tax relief for certain investment goods and periods. The Myanmar Investment Commission (MIC) and the Directorate of Investment and Company Administration are mandated with implementation of the law. The revised law will extend the tax holiday from three to five years and allow foreigners leases on land for 30 years plus 30-year extensions. However, foreign investors will be required to progressively employ more Myanmar citizens.

The government guarantees investors against nationalization and expropriation. Foreign currency from profits, capital gains, and salaries can be transferred.

In addition, the country has enacted the Special Economic Zone Law and two SEZs are approved. SEZs offer additional benefits to foreign investors. The Dawei Special Economic Zone is close to Thailand and plans a deep sea port, power plants, and an industrial estate. The project value is equivalent to the country’s GDP today.11 The exchange rate regime is being liberalized with a floating exchange rate adopted in April 2012. Consideration is given to allow foreign bank joint ventures and branches. A securities and exchange commission law is being drafted as well as a capital markets law.

Myanmar has its Arbitration Implementation Act of 1937, but lacks implementation thereof. Myanmar is considering joining the New York Convention on the Recognition and Enforcement of Arbitral Awards in the near term. Trademark registration is possible.

Currently economic sanctions against the country are severe. To date, the United States prohibits investment or facilitation, export of financial services, and imports related to Myanmar. Any dealings with Specially Designated Persons (SDNs) deemed to be involved in human rights abuses is prohibited. The European Union restricts investment, trade, and services with respect to defense and military, extractive industries, forestry, and steel and iron.

However, the EU travel and visa ban has been lifted. Generally, the ease or lifting of most restrictions is expected if Myanmar continues to liberalize its political regime.

The history of the country and its people augurs well for rapid development and progress. Provided political change continues, economic attractiveness should follow. Most building blocks for a frontier economy are in place and the English legal system is a very good starting point.

With a labor force of more than 40 million people, mostly literate and conversant in English, access to natural resources and a very low-cost base, manufacturing industries would benefit greatly. If the legal system strengthens and sanctions are lifted, foreign investment is likely to follow. All industrial sectors should benefit and develop accordingly. Even just getting back to the heyday of the garment and textile industries would be an accomplishment. Health care and education, tourism, retailing, and telecoms are some of the most promising service sectors. Construction of infrastructure but equally of housing, low cost and urban, will be in high demand.

Membership in ASEAN and the growing importance of regional trade (25 percent of all trade by ASEAN members and 53 percent of all exports by Asian economies are intraregional according to a WTO 2011 report), could allow Myanmar to become a low-cost producer for neighboring and booming economies and attract significant investment. At the same time, the large population has the potential to gradually migrate toward more consumption of basic goods and services and develop into a noticeable low-to-middle market.

Long considered an unspoiled, charming, vast but sleepy country about the size of the United Kingdom in area, Laos, with some 6.5 million inhabitants, has emerged from nearly three decades of self-imposed isolation to become one of the fastest-growing economies in Asia and a recent destination for foreign investment. In 1986 the government shifted away from a Soviet-style command economy and began to introduce some market reforms that developed private sector activity.

Laos has a one-party political system with active central planning by the government. The head of state is the president and head of government the prime minister. Government policies are determined by the party through the powerful 11-member Politburo and the 50-member Central Committee.

The National Assembly, which added seats at every election, approves all new laws, although the executive branch retains the authority to issue binding decrees.

Since the decentralization, the forces of globalization (in 2004 Laos gained Normal Trade Relations status with the United States) and regionalization (ASEAN membership) have further driven Laos toward a market-oriented economy. The country’s GDP (PPP) was US$1.8 billion in 1984 and US$7.3 billion in 2010. The economy has expanded at a rate of over 7 percent per annum since 2004, driven by foreign investment in hydropower, mining, agriculture, and tourism. GDP is expected to increase by 7.6 percent per annum on average from 2011 to 2015. Tourism is the fastest-growing industry in the economy. The number of tourist arrivals tripled in 10 years to 1.2 million tourists in 2010.

Several factors are expected to underpin its growth over the next decade, including: strong demand for its vast resources, particularly by its industrializing neighbors; accelerating integration of the ASEAN group of nations and with China; favorable demographics offered by its young population; and the return of successful Laos expatriates to their homeland to provide sorely needed capital and entrepreneurial expertise.

Laos is a relatively poor, landlocked country with an inadequate infrastructure and a largely unskilled workforce. The country’s GDP (PPP) in 2010 was approximately US$7.3 billion, with per capita income (PPP) estimated at US$1,176. Agriculture dominates the economy, employing some 75 percent of the population and producing approximately 31 percent of GDP, while the industrial sector and the service sector account for approximately 25 percent and 39 percent, respectively (see Table 13.3).

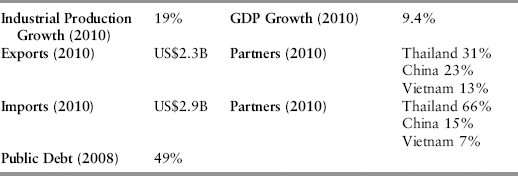

TABLE 13.3 Lao PDR Economic Snapshot

Source: National Statistics of Lao PDR, author’s analyses.

During the global economic slowdown of 2008 and 2009, the Lao economy held up very well compared to its neighbors as GDP expanded at a brisk rate of 7.8 percent (2008) and 7.1 percent (2009), making Laos the second fastest-growing economy in Asia after China. The main reasons for this resiliency were likely the country’s limited integration with global monetary and trading networks. Also, resource-rich Laos was a major beneficiary of rising commodity prices during the period.

More than 80 percent of the country’s trade is with the neighboring countries of Thailand, Vietnam, and China. Only a small portion of Laos’ exports are manufactured products or finished goods. Instead, most items sold abroad are basic products, raw materials and semi-processed goods. The largest export categories are minerals (30 percent of total), base metals and related products (27 percent), textiles (including garments 14 percent), and jewelry and gemstones (6 percent). As a less developed country, Laos enjoys preferential trade tariffs and other trade benefits from the European Union and other OECD nations under the “everything but arms” program.

Laos has followed a market-oriented reform program since the launch of the New Economic Mechanism policy in 1986, although partial reforms were introduced as early as the late 1970s. Many current economic problems stem from the legacies of central planning and the difficulties associated with the shift from central planning to market forces. The government’s ability to enact reforms is hindered by a lack of consensus within the ruling party over the suitable pace of reform. Although top party leaders are regarded as from its reformist wing, their approach to reform has been gradual in the face of ideological and political resistance.

The Lao PDR government depends heavily on foreign investments to supplement foreign aid and lift the country from its underdeveloped status. The creation of additional jobs is a major objective, as Laos has a very young population (60 percent of its people are under the age of 25) and the workforce is expected to expand rapidly. As part of that plan, the Lao government seeks to promote greater foreign investment in agriculture, electricity generation, alternative energy, hotels and tourism, and logistics and services. It is also promoting expanded investment in infrastructure as part of its plan to transform the country from “land-locked to land-linked” as a trade crossroads in mainland Southeast Asia.

Foreign investment will continue to play a major role in Laos’ development. However, foreign investors are restricted from engaging in certain commercial activities without the permission of the Lao government, such as forest exploitation, accounting, tourism, heavy vehicle or machinery operation, and rice cultivation.

Foreign direct investment has surged in recent years, coming mainly from neighboring Thailand, China, and Vietnam (nearly 80 percent of FDI approvals in recent years). Investments from Thailand and Vietnam increased notably after 2004 when the second revision to the investment law made major changes to investment policy and provided improved incentives.

Chinese investment into Laos tends to focus on companies that can provide natural resources (minerals, agricultural goods, etc.). Often these are government linked projects that have received long-term concessions from the Lao government. Many of the largest Chinese investors tend to come from provinces located close to Laos, such as Yunnan province.

Thai and Vietnamese businesses take a different approach, as they are mainly prominent business groups that seek to extend their presence into neighboring Laos. Thai investors have successfully extended well-known Thai brands into Laos (such as banks, building materials, and retail businesses) and have also focused heavily on the hydropower industry, which exports much of its output to Thailand. The Vietnamese are also very active in the financial sector and construction services.

One criticism leveled against foreign investment is that many of the companies seek only to acquire raw materials and basic goods from Laos and then process them elsewhere. The Lao government has moved in recent years to require greater value addition in Laos and thus stimulate investment in processing facilities. This is most evident in the wood-processing industry where the sale of unprocessed logs and timber has been halted. Similar plans are being considered for the agricultural sector, as Laos currently has some basic processing capacity for farm goods.

Another important source of foreign investment comes from individuals of Lao descent, the overseas Lao who have focused on developing small to medium enterprises (SMEs). Many of these individuals are successful businessmen who emigrated to North America, Australia, or Europe in the 1970s. As they usually hold passports from their adopted countries and do not have Lao passports, their investment is classified as if they were foreigners. They are an important source of capital and entrepreneurial expertise to the SME sector.

Laos is blessed with an abundance of natural resources, including vast minerals, large forested areas, and, with its extensive water resources, the opportunity to develop large hydropower and agriculture industries. Relatively little exploitation occurred during the country’s self-imposed isolation from the mid-1970s until recently.

Given the hefty rise in most commodity prices over the past decade, Laos is now well positioned to develop and exploit these resources. The government has expressed its interest in pursuing a strategy of sustainable development and is keenly aware of the damage caused to the economy and society of its neighbors as they aggressively developed their resources in the past few decades.

Under an ambitious plan to become the “Battery of Asia,” Laos is expanding its power-generating capacity so as to export electricity to its rapidly industrializing neighbors. The Mekong River and its tributaries, the Nam Ou and Se Kong rivers, flow through the country for over 2,000 kilometers and provide ample water supplies that provide Laos the potential to produce up to 20,000 megawatts (MW) of hydropower capacity. Plans are in place to expand installed capacity from nearly 2,000 MW at present to 5,000 MW by 2020. Earnings from these projects, if used wisely, can be used to solve a number of important social and economic issues, such as improving the country’s domestic infrastructure and upgrading its academic systems.

Laos has been successful in attracting foreign investors from both Asia and the OECD into its hydropower program. Within Asia, the only countries which have a similar or greater benefit from hydropower development are the Himalayan countries of Nepal (estimated potential of 30,000 MW) and Bhutan (estimated potential of 20,000 MW).

Laos has large quantities of gold, copper, aluminum, and potash and is also believed to hold important deposits of lead-zinc, tin, iron, gypsum, and coal. Mining operations in recent years have accounted for nearly 10 percent of GDP and can expand substantially since the government has only granted exploration licenses for 21 percent of the total land area believed to hold mineral deposits. Mining operations have begun on less than 10 percent of that area. At present there are about 150 mining projects at various stages of planning, but many licenses appear to be held by companies that lack the financial resources or expertise to develop the projects.

Two major mining companies, Min Metals Lao and Phu Bia Mining, are increasing their extraction of copper and gold and now produce more than double their output in 2008. An estimated 2 to 2.5 billion tons of bauxite await extraction in the southern provinces of Champassak, Sekong, and Attapeu. Potash, an essential element in the production of fertilizer, is becoming increasingly valuable as world prices of fertilizer continue to rise. Several Chinese and Indian businesses are competing for the right to mine potential potash deposits south of Vientiane that could yield almost 50 billion tons.

The government remains concerned that mining resources should be developed in a sustainable manner. In July 2010, it announced it would suspend new mining projects until further notice and would improve its monitoring of mining concessions.

Laos shares a border with four other ASEAN nations and development of the country’s transportation infrastructure is a key strategy to integrate resource rich Laos with potential markets in the region and is also designed to reduce its typically expensive transport costs. Much of the improvement to roads and the rail system are being funded by international donors and grants by foreign governments. Presently three major highway networks are under construction that will pass through Laos and will convert Laos from a land-locked nation to a land-linked nation.

Laos currently does not have a functional railway network, but a Chinese railway project has been proposed which would link Laos to southwestern China. The 400-km line will link the Lao cities of Luang Namtha, Luang Prabang, and Vang Vieng with Vientiane and China’s Yunnan province. The railway is a joint investment between Chinese companies, which have a 70 percent stake in the project, and the Lao government, which holds the remaining equity.

Recently, the Thai government has proposed a plan to complement the Chinese project and extend the line from Vientiane into Thailand and on to Malaysia by establishing a high-speed train that would integrate with its existing rail system in Thailand. This immense project could provide a significant boost to Laos’ GDP, develop numerous rural areas in Laos, and dramatically reduce transport costs and transit times for Lao exports.

Laos is an extremely young country with a median age of only 19 years. It is not uncommon to find families with five or more children. These young consumers will bolster consumption as they require housing, major goods, and services. Laos is not likely to develop a large manufacturing sector and most consumer goods will be imported, offering significant opportunity for substitution production facilities.

Laos is well suited to provide labor to its neighbors and ASEAN. There are plans to establish Thai and Vietnamese industrial estates close to the borders of Laos to tap Lao labor and produce goods for sale in their countries and Laos. For Thailand this is especially attractive as the two countries share a comparable culture and a similar language. Eighty percent of the Lao population is said to live near the Thai border and can meld easily with the people of Thailand’s northeastern region of Isaan, most of whom are ethnically Lao, as the area was once part of the Lao kingdom.

An estimated 500,000 to 600,000 overseas Lao live largely in North America, Europe, and Australia. These expatriates are returning to Laos in increasing numbers and many have returned indefinitely to establish businesses and settle in Laos. Many of these individuals emigrated in the late 1970s as the communist regime (Pathet Lao) seized power.

The Pathet Lao allowed their residents to depart the country, but at a cost of losing their passports and citizenship. The only outward discrimination against returnees is that they cannot own land as they do not hold Lao citizenship, and hence are treated as foreigners in this regard. As many returnees want to buy homes, an initiative is considered by the government to establish a process for them to buy land. In the future we expect to see modern housing in Vientiane and other cities, full of expat owners and their families.

Many of the new startups and SME investments are pioneered by the overseas Lao, who thus fill a vital role of creating jobs and providing entrepreneurial innovation. Having had a taste of Western-style consumerism and having recently enjoyed Western-level salaries, these expats will play an increasingly important role in bolstering consumer spending in Laos and modernizing its retail and service sectors.

In September 2007, the Bank of Lao PDR (BOL) and the Korean Exchange (KRX, 49 percent shareholding) signed a memorandum of understanding (MOU). The Securities and Exchange Commission Office (SECO) was formed and in January 2011, the Lao Securities Exchange (LSX) was officially opened with two initial public offerings (IPOs): Eléctricité de Lao Generating Co (EDL), a state-owned power company and Banque Pour Le Commerce Extérieur Lao (BCEL), a state-owned bank. Their IPOs raised a combined US$140 million. Share offerings have attracted significant international and domestic investor interest, with heavy oversubscription of foreign investors from over 20 countries. Total funds raised by these two Laotian companies are almost three times larger than all IPOs (US$50 million in total) at the Mongolian Stock Exchange (MSE) for the past six years.

To be listed, companies have to be profitable for at least one year, demonstrate transparency and sound management, and have a sound business plan. A share offering must not exceed 10 times the company’s registered capital. The procedures for an IPO are generally similar to those in other countries. Once SEC approval has been obtained, a prospectus for potential investors must be prepared and publicly advertised within 60 days. Securities may then be sold by SEC licensed brokers within 90 days (or 120 days). There are currently two licensed brokers.

Currently, securities may be bought, sold, and transferred at the LSX only in Lao kip; however, the SEC appears to be considering other currencies. Foreign investors are entitled to purchase securities. However, some restrictions apply: Individual investors may not hold more than 10 percent of total shares of a single company, and a group of investors together may not hold more than 49 percent of total shares of a single company. The SEC has stated that as long as there are no industry restrictions (e.g., media industry), listed companies may allow any percentage of foreign ownership.

EDL Generating Company (EDL Genco) is currently the largest listed company on the LSX and operates seven hydropower dams totaling 387 MW; they acquired an additional 210 MW in 2011 and expect to grow to 1,096 MW by 2016.

The government of Laos established the company to raise funds to invest in acquiring the power plants and assist in the development of the Laos power sector as well as become the first publicly traded stock on the Laos Stock Exchange.

The company sells electricity to EDL (the government holding co) under a series of power purchase agreements with terms of 30 years and an option to extend 10 years. Company sales are denominated in Lao kip and not US dollars The company does not own or operate transmission lines or distribution assets, these services are conducted by EDL Genco.

EDL-Genco offered 25 percent of its shares for purchase, with 10 percent of its IPO going to foreign investors and 15 percent to domestic investors. The government holding company EDL will maintain a 75 percent holding. Thailand’s Ratchaburi Electricity Generating Holding PCL is the largest single minority shareholder through a US$43.3 million holding in the company.

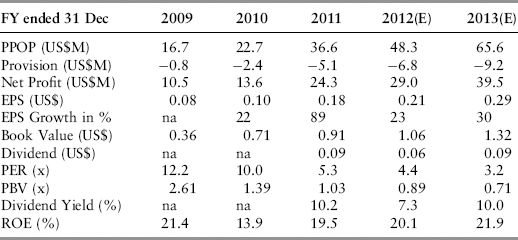

The stock performed strongly at the outset during which several international investors rebalanced their portfolios. Over the course of the year 2011, the stock moved sideways slightly below issuing price (excluding dividends paid) and is now moving in a 5 to 10 percent range above the IPO price (see Figure 13.5). With a 10 percent dividend yield (see Table 13.4) and a long-term stable outlook for electricity generation and export sales, this investment—despite being listed on an unclassified market – has all the hallmarks of an early investment into an emerging economy.

TABLE 13.4 EDL Financials and Valuation Report

The second listed share is the largest commercial bank of the country, Banque Pour Le Commerce Extérieur Lao Public (BCEL).

BCEL was established at the end of 1975 as a specialized branch of the former state bank (Central Bank). In November 1989, BCEL was transformed into a full commercial bank. BCEL’s activities continue to grow with 18 branches, 20 service units, and 10 foreign exchange service offices. BCEL has over 100 correspondent banks worldwide.

BCEL offered 20 percent of total shares to the public, of which 75 percent were allotted to Lao citizens and 25 percent to BCEL’s staff. Foreign investors were not eligible to participate in the IPO but can purchase shares in the market.

The stock performed similarly to the EDL stock and trades now above the offering price (see Figure 13.6). Given that foreigners were excluded from the IPO, this stock may demonstrate the pent-up demand in the country for financial assets

As with EDL, financials (Table 13.5) and consequential valuation seem reasonable given dividend yield, return on equity, and price earnings ratio.

TABLE 13.5 BCEL Financials and Valuation Report

Laos sports a number of potential future IPOs and several companies have expressed their interest to list. The Lao-Indochina Group Public Company is planning to be listed on Lao Securities as the first private company. Growing cassava and tapioca is the main focus of its business.

Enterprise of Telecommunications Lao is a state-owned company. The government intends to sell 30 percent of its shares. Five percent will be offered to ETL staff, 15 percent to Lao nationals, and 10 percent to foreign investors. ETL has about 960,000 mobile phone subscribers and is confident it can attract more customers despite strong competition in the domestic telecom market.

Lao World Group, privately owned, is a diversified group that invests in agriculture, engineering, construction, hotels, and tourism sectors. Lao World Group is known to be a prominent group of companies working with the government in various development projects.

Lao Airlines is wholly owned by the Lao government. It is the national airline of Laos, operating domestic services to 10 destinations and international services to Cambodia, China, Thailand, Vietnam, and Singapore.

Lao Brewery Company is a 50-50 joint venture between a state firm and the Danish brewer Carlsberg and is also looking at an IPO. The company’s beer production capacity will reach 310 million liters in 2012 and holds a 98 percent market share.

The kingdom of Cambodia with 15.5 million people is considered a new economy. The country faced civil conflict for over 30 years from the mid-1960s to the late 1990s. Political stability improved over the course of the early 2000s and the economy began to gather momentum with average GDP growth per annum of 9.5 percent between 2000 and 2008.

Cambodia’s system of government officially is a multiparty liberal democracy under a constitutional monarchy. The current system was established and adopted in September 1993. Under the framework established by the constitution, HM the King serves as the head of state for life but does not govern. HM serves as symbol of the unity and continuity of the nation.

The head of government, elected since 1998, is the prime minister. The National Assembly constitutes the first of the two legislative branches of the system of government. Its 122 members are elected by popular vote to serve five-year terms in parliament. The second legislative branch of the government is the Senate. The Senate currently has 61 members, whose appointments are officially made by HM the King.

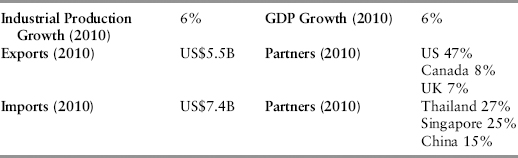

The growth of the Cambodian economy has averaged 7 percent on an annual basis since the government began its measured shift toward free market economic policies in late 1980s. Today the Cambodian economy is driven by four sectors: agriculture, tourism, property/construction, and light industry (primarily garment and footwear manufacturing). GDP per capita (PPP) reached US$2,100 in 2010 (see Table 13.6).

TABLE 13.6 Kingdom of Cambodia Economic Snapshot

Source: National Statistics of Cambodia.

Since 1995, the agricultural sector’s contribution to GDP has fallen from 45 percent to 31 percent as industry and services have grown faster, although agriculture has seen a resurgence of investment. Rice is by far the largest crop, with rubber and cassava second but growing rapidly in recent years. Sixty percent of the workforce is employed in the agriculture sector.

The garment industry is considered the biggest industrial employer in Cambodia, employing more than 350,000 workers—about 5 percent of the workforce in 300 factories contributing more than 70 percent of Cambodia’s exports. The industry began to grow after the country passed a new labor law encouraging labor unions and allowed the International Labor Organization (ILO) to inspect factories and publish its findings. In turn, the United States signed the least developed countries (LDC) agreement, agreeing to cut tariffs on Cambodian garment exports and buying 70 percent of all of the country’s textiles in the 1990s.

Tourism is Cambodia’s fastest-growing service industry, representing 18.4 percent of GDP and 14 percent of employment in 2010. In 2011, 2.8 million people visited Cambodia and tourism is expecting growth at 15 percent in the coming years.

The construction industry was affected by the global financial crisis but got back on track in 2010 and 2011, with investment reaching US$840 million over 2,149 projects and government-approved investment in 2011 worth US$1.7 billion.

In 2005, exploitable oil deposits were found beneath Cambodia’s territorial waters, representing a potential new revenue stream for the government if extraction proves commercially viable. Mining for bauxite, gold, iron, and gems also is attracting investor interest, particularly in the northern parts of the country.

The major economic challenge for Cambodia over the next decade will be to create employment opportunities. More than 50 percent of the population is less than 25 years old.

The IMF assessment of Cambodia’s fiscal policy has been broadly positive. Fiscal restraint has led to consistent reductions in the budget deficit over the past few years. However, revenues as a percentage of GDP remain low. Tax collection and legislation have been of particular concern. The authorities are now placing a stronger policy emphasis on the enforcement and reform of taxation law.

In 2006, the Ministry of Economy and Finance of the Kingdom of Cambodia and Korea Exchange (KRX) signed a memorandum of understanding on the development of the securities market in Cambodia and in 2009 established a stock market, the Cambodia Securities Exchange Co, Ltd, a public enterprise with a 45 percent shareholding by KRX under the supervision of the SECC, the Securities Exchange Commission of Cambodia.

With advice from KRX and input from the private sector, the SECC established the listing requirements. Companies need to have a three-year history of complete financial and tax records, a current capital of at least US$1.2 million, and an annual net profit of over US$ 125,000, plus an accumulation of US$250,000 of net profit in the previous three years.

The company’s board shall be composed of at least 5 and not more than 15 members with at least one-fifth independent directors. Where the company employs non-Cambodians as independent directors, such directors shall have worked six months in Cambodia.

For companies with capital below US$5 million, the issue size shall be at least 20 percent of the share capital, otherwise it shall be at least 15 percent of the share capital. Twenty percent of the total public offering is reserved for Cambodian citizens and 80 percent is open to the global market.

There are four registered brokers and seven licensed securities underwriters in addition to two securities dealers and three investment advisors.

PPWSA was founded in 1895 and currently produces and supplies potable water to consumers in Phnom Penh and the surrounding areas by treating raw water from the rivers surrounding Phnom Penh. Water supply accounts for approximately 90 percent of revenues. Other services include new water connections and water supply consulting services.

The company currently (2011) operates three production facilities with a total capacity of 330,000 cubic meters/day and is constructing a fourth facility that will add 260,000 cubic meters/day by 2015 (130,000 cubic meters/day in 2013 and another 130,000cubic meters/day in 2015). PPWSA’s distribution network is currently approximately 2,000 kilometers covering 90 percent of Phnom Penh. The efficiency of the network is good, with only 5 to 6 percent water loss, down from 20 percent + 10 years ago.

The tariff structure for water is progressive. Tariffs were last revised in 2001 and there is no further review scheduled. The average tariff is US$0.25 per cubic meter versus US$0.30 per cubic meter in Thailand and US$0.45 to $0.50 per cubic meter in the Philippines. PPWSA has achieved a 99 percent collection rate on billing in recent years.

The company is considered well managed from an operational standpoint. It has a seven member board of directors, all of whom are Cambodian and five of whom are government officials. The company’s financial statements are audited by PWC.

The company has steadily grown its customer base (7 to 8 percent per annum) but revenues have grown faster (8 to 10 percent per annum) due to a more favorable customer mix. Operating expenses have been 45 to 50 percent of revenues. Electricity and staffing are the major operating expense items. The company has generated a healthy ROE.

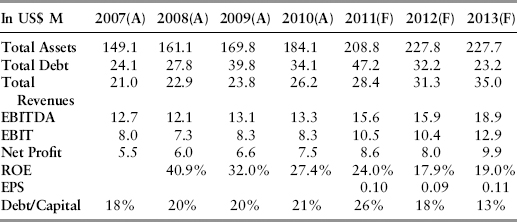

Revenues are expected to grow 10 and 12 percent in 2012 and 2013 respectively due to new customers and industrial/commercial customers paying a higher tariff (see Table 13.7). Phnom Penh is expanding rapidly, with the population forecast to increase from 1.4 million in 2009 to 2.2 million by 2020. Dividend policy has not been defined but historically the company has paid out 9 to 10 percent of profits.

TABLE 13.7 PPWSA Financial Snapshot

Source: PPWSA, prospectus, Tongyang Securities (Cambodia) Ltd. March 2012, Leopard Capital.

The company has fairly low leverage. Most debt is low-cost debt from government and development organizations such as JICA, AFD, and the World Bank. Leverage will increase modestly to fund new plants.

PPWSA offered 13.5 percent of its shares to the public through a book building process at a price range of 4,000 riel (national currency of Cambodia and equivalent to US$1) to 6,300 riel (US$1.57) for gross proceeds of US$13 to US$20 million. The CSX intention is to have stocks trade only in riel. Following the offering, the government will continue to own 85 percent of the outstanding shares subject to a one-year lock-up. 1.5 percent of the company’s shares will be reserved for with a three-year lock-up period. The book-building process generated huge demand and was oversubscribed 17 times with more than 800 foreign and domestic investors putting in offers. A small number of shares were subsequently offered at the book building price by way of subscription.

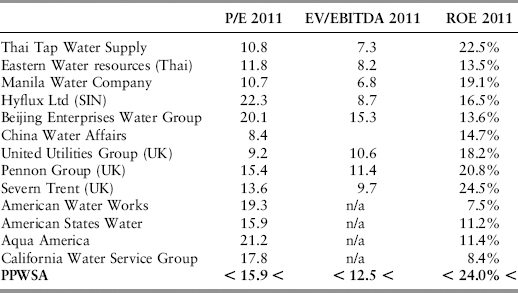

In terms of valuation, PPWSA is at the high end of comparators across the region (see Table 13.8).

TABLE 13.8 PPWSA Comparators

Source: Leopard Capital.

PPSWA pricing appeared to be pretty aggressive. However, underlying growth potential, performance, and excess liquidity may have been a key factor in the book building price finding.

Despite the high valuation and the upper end IPO price of Riels6,300 (US$1.57), the stock gained some 60 percent from its IPO value during the first few days of trading and was trading at Riels10,200 (US$2.54) on April 20, 2012. This demonstrates both latent demand and opportunities in unknown markets. Given the great success of the first issue, several other state owned or related companies are now looking to follow soon.

As in other developing stock markets, additional early listing candidates are generally large utilities, telecom companies, and financial institutions. Cambodia is no different but there are reportedly a number of garment manufacturing companies, hotel companies, and others contemplating a listing (see Table 13.9).

TABLE 13.9 Cambodia IPO Pipeline

| Telecom Cambodia | Communications | Founded in 2006, state-owned corporation considered the principal telecom company of the country |

| Sihanoukville Autonomous Port | Commerce | Founded in 1960, PAS is a government agency that operates the country’s sole deep water port |

| ACLEDA Bank | Bank Services | Founded in 1993 as an NGO providing microfinance loans, now a full service commercial bank with 234 offices nationwide |

The three main Mekong river economies represent individually and collectively one of the last true frontiers of rapid development. While today not classified as frontier economies by international standards, their endowment with human and natural resources and their strategic location embedded in historically strong legal systems augurs well for the future. As trading partners within ASEAN and as rapidly growing labor and consumer markets, Mekong river economies are prime candidates to watch as investment destination. Tiny and new stock markets are a first step in joining the ranks of investable markets.

Membership in ASEAN and its people endowment will allow Myanmar to rapidly shed the least-developed economy status and become a fast-growing support economy to ASEAN and wider Asia. This looks like a frontier market in the making and its future depends only on the political will to making it happen and convincing the international community that efforts are sincere and sustained.

In the same vein, Laos offers upcoming opportunity with advantages to foreign investors over some of its neighbors (China, Thailand, and Vietnam). Foreign firms may wholly own and operate a business in any promoted sector, which includes a broad range of industries, many of which are protected in other countries. The countries nascent stock market could develop over the coming years to list attractive investments.

It’s hard to find a country that has recovered faster from more than 30 years of turmoil, ending only in the mid/late 1990, than Cambodia. The opening of the Cambodian Securities Exchange is an important milestone for Cambodia on its path to becoming an accepted frontier economy. With a number of larger companies, the country may well develop an attractive, although smaller, stock market.

1. UBS, Investment Research, April 2012 quoting IMF.

2. UBS, ibid.

3. Central Statistical Office, Ministry of National Planning and Economic Development, Monthly Economic Indicators, December 2011, www.csostat.gov.mm.

5. UN data, various.

6. World Trade Report 2011, WTO.

8. Central Bank of Myanmar, www.cbm.gov.mm.

9. Reuters, Agence France Press, Gulf News (May 14, 2012).

10. Hogan Lovells, “Change and Opportunity in Myanmar” (April 2012).

11. UBS, ibid.