Many investors and executives tend to see businesses in their local and regional environment. A much-overlooked subject is the responsibility with respect to good governance and avoidance of corruption. The international community, however, is increasingly rallying support for a global system of combating inappropriate behavior no matter where it occurs.

Institutional investors will need to devote more resources to this issue or risk facing unpleasant questions and possibly consequences.

One of the critical ingredients in considering, making, or having an investment in developing economies is access to information and some degree of reliability of such information. Aggregate information we use to make decisions is often nothing but the accumulation of poor lower-level information. This is particularly relevant when analyzing company reports, research, and other external information. Looking at the sources of mistakes and flawed information flows is a necessary corollary for any developing market investor.

Robert-Jan Temmink

Quadrant Chambers

Standing in the dock of an English Crown Court facing trial for an imprisonable offense is an unpleasant place to be any time. Imagine that the accused is the CEO of a major US company who is there not because of any act he did while sitting in his office somewhere in the United States, but because of the act of one of his junior employees whose name he has never heard, or an employee of a subsidiary or maybe that of a supplier, or as a result of an act done in a far-flung country that the CEO could not even have found on a map. Such a scenario is entirely possible as a result of the UK Bribery Act 2010, which came into force in mid-2011. There has already been one successful prosecution in the United Kingdom of a corrupt court clerk; most commentators are expecting a headline-grabbing multinational trial in the near future, a showcase of the global reach of this important legislation.

This chapter highlights a few of the legal issues facing directors, individuals, and businesses considering investing in emerging markets in the context of this far-reaching piece of English legislation, legislation which now challenges the US Foreign Corrupt Practices Act for the extent of its long-arm nature. Murky business practices and even practices that the United States considers to be clean (facilitation or “grease” payments) now potentially render international individuals and global businesses subject to prosecution within the United Kingdom.

Prior to the new act coming into force, the United Kingdom law that criminalizes acts of bribery and corruption was to be found scattered across the common law and no less than 12 different statutes dating from as long ago as 1551. All of that has been swept away by the new Act.

The United Kingdom came under increasing pressure to reform the existing legislation. The key driver behind the Act was the Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development (OECD) Anti-Bribery Convention and its revised recommendation produced in 1997, the purpose of which, according to the secretary general of the OECD, is to tame “the dark side of globalization.” In 2009, the OECD produced a Recommendation on Further Combating Foreign Bribery, which called on parties to review the position on small facilitation payments, increase the effectiveness of corporate liability, protect whistleblowers, and encourage the private sector to adopt stringent anti-bribery compliance programs. The Annex to the Recommendation gave good practice guidance on compliance.

The six principles produced by Transparency International, the world’s leading non-governmental anti-corruption organization, underpin both the Anti-Bribery Convention and the UK Act. The principles are risk assessment, top-level commitment (a business culture in which bribery is unacceptable), due diligence concerning business partners, clear policies and procedures, effective implementation, monitoring and review of controls, and external verification of their effectiveness. Other international instruments include the United Nations Convention against Corruption (2003), European Union measures such as the Convention on the Fight against Corruption involving Officials of the Member States of the EU (1997), and a Framework Decision on Corruption in the Private Sector (2003). The latter requires the criminalization of both active and passive corruption (giving and receiving a bribe), and stipulates that legal persons may be held accountable. The Council of Europe Criminal Law Convention on Corruption (1998) and additional Protocol (2005) covers bribery of domestic and foreign officials as well as private sector corruption, trading in influence, money laundering, and accounting offenses connected with corruption offenses. The Convention includes provisions on corporate liability, accounting offenses, and mutual legal assistance. The Protocol covers bribery of domestic and foreign arbitrators and jurors.

The act abolishes the common law offenses and sweeps away the nineteenth- and twentieth-century Prevention of Corruption Acts. The purpose of the act is to codify the common law principles and enshrine the principles just set out in one unifying piece of legislation.

Using a novel form of drafting (the introduction of cases, samples of statutorily restricted behavior), the new offenses created by the Act reach directors, managers, and secretaries of companies as well as the corporate bodies and partnerships themselves. They have very broad jurisdictional reach that can affect any business, or part of a business, in the United Kingdom, even if the underlying behavior does not have any substantive connection with the United Kingdom.

Broadly, the act creates four categories of offense:

The latter offense is a strict liability offense for companies and extends to “associated persons,” which includes employees, agents, or subsidiaries, subject to the defense that the company had in place adequate procedures to prevent the bribery.

The secretary of state in the United Kingdom is required by the Act to publish guidance,1 the legal status of which is a little uncertain and yet to be tested in court, that sets out procedures that relevant commercial organizations can put in place to prevent people associated with them from bribing. The introduction to the guidance by the justice secretary is salutary:

Ultimately, the Bribery Act matters for Britain because our existing legislation is out of date. In updating our rules, I say to our international partners that the UK wants to play a leading role in stamping out corruption and supporting trade-led international development. But, I would argue too that the Act is directly beneficial for business. That’s because it creates clarity and a level playing field, helping to align trading nations around decent standards. It also establishes a statutory defense: organizations which have adequate procedures in place to prevent bribery are in a stronger position if isolated incidents have occurred in spite of their efforts.

Some have asked whether business can afford this legislation – especially at a time of economic recovery. But the choice is a false one. We don’t have to decide between tackling corruption and supporting growth. Addressing bribery is good for business because it creates the conditions for free markets to flourish.

The rhetoric acknowledges the economic burden on companies engaged in international trade of complying with the legislation and the risks of not taking this legislation seriously. In England and Wales, no prosecutions under the Act may be instituted without the consent of the Director of Public Prosecutions (DPP), the Director of the Serious Fraud Office (SFO), or the Director of Her Majesty’s Revenue and Customs Prosecutions. The Director of the SFO and the DPP have also issued guidance and given lectures concerning the principles they intend to apply to any circumstances that may give rise to a decision to prosecute. The extent and legal effect of such guidance has yet to be tested in the courts.

Penalties range from fines to imprisonment for up to 10 years, or both, and can extend not only to corporate bodies but also to the senior officers of the corporate bodies if the offense were committed with their consent or connivance.

The section 1 offense prohibits a person (which definition also includes a body corporate) from offering, promising, or giving a financial or other advantage:

The section 2 offense prohibits a person from requesting, agreeing to receive, or accepting a financial or other advantage (a bribe) intending that a relevant function should then be performed improperly, either by that person or by another person at the request of, or with the assent or acquiescence of, the first person. Again, it does not matter whether the bribe is requested, received (or agreed to be received), or accepted directly or through a third party; nor does it matter whether the bribe is or will be for the first person’s benefit, or for the benefit of another person. Furthermore, it does not matter whether the person requesting or accepting the bribe knows or believes that the performance of the relevant function is improper.

A “function or activity” is “relevant” for the purposes of the Act if it fulfills a number of criteria. First, it has to be:

The relevant function or activity has also to be performed by a person who is expected to perform it:

Section 6 provides that it is an offense for a person (which definition also includes a body corporate) to offer, promise, or give any financial or other advantage to a foreign public official, either directly or through any third party, where the person’s intention is to influence the official in his capacity as a foreign public official and the person intends to obtain or retain either business or an advantage in the conduct of the business. “Foreign public official” is defined in section 6(5) of the Act as an individual who holds a legislative, administrative, or judicial position of any kind, whether appointed or elected, in a country or territory outside the UK; or who exercises a public function for or on behalf of a country or territory outside the United Kingdom or for any public agency or public enterprise in such a country or territory, or who is an official or agent of a public international organization.

Section 7 creates a strict liability offense on commercial organizations where a person associated with the commercial organization bribes another person (where the associated person commits an offense under sections 1 or 6) intending to obtain or retain either business or an advantage in the conduct of business save where the commercial organization can prove that it had in place adequate procedures designed to prevent bribery. “Associated person” is defined in section 8 of the Act as a person who performs services for or on behalf of a commercial organization. The capacity in which that person performs services for the organization does not matter and the person can therefore be an employee, agent, or subsidiary of the organization. All the relevant circumstances can be taken into account by a court when determining whether an individual is or is not an associated person of a commercial organization and it is assumed that an employee is an associated person. It is this wide definition, coupled with the territorial extent of the Act, that poses the most risk for companies investing in emerging markets, particularly when investing in markets where the standards of business and ethics may not be those expected in the United Kingdom.

Uncontroversial, section 12 of the Act provides that the offense under sections 1, 2, and 6 are committed if any act or omission that forms part of those offense takes place in the United Kingdom. More controversial, the Act also criminalizes acts or omissions abroad by individuals with a close connection with the United Kingdom if those acts or omissions would form part of the offense if they had been done or made in the United Kingdom. “Close connection with the United Kingdom” is defined in section 12(4) of the Act and includes a United Kingdom citizen, an individual ordinarily resident in the United Kingdom, and a body incorporated under the law of any part of the United Kingdom.

An associated person can also be a joint venture—when deciding whether to invest in an emerging market companies that have any connection with the United Kingdom will now need to be assiduous in ensuring that they have done their due diligence on any joint venturer or agent abroad to satisfy themselves that they have in place adequate procedures to prevent bribery. This concept of adequate procedures is examined in further detail later. The concept can lead to problems if, for example, that joint venturer is a US corporation. Under the equivalent US legislation, the Foreign Corrupt Practices Act, it is not an offense to make what are called facilitation or grease payments, that is, payments to a foreign government employee to provide what you are entitled to have, for example giving a border guard $20 to stamp a passport immediately, instead of waiting a few hours or days. But under the English legislation, that is capable of being an offense, and you have to hope that the prosecuting authorities would consider that it was not in the public interest to prosecute.

An investor might think this a rather unsatisfactory state of affairs. It is, perhaps, analogous to the famous judicial comment in the Vestey tax case about it being better to be taxed by statute rather than untaxed by Inland Revenue concession: It would be better to know that making such a trivial payment was within the law rather than be put at risk of a prison sentence if a prosecuting authority decided, for whatever reason, to make an example and prosecute.

The person paying the bribe does not have to be prosecuted before the organization is prosecuted. Thus a UK company may incur liability for the acts of foreign nationals working abroad, even if their acts have no connection with the United Kingdom.

There is a restricted defense. The organization must prove (on balance of probabilities) that it had in place “adequate procedures” designed to prevent associated persons from undertaking such conduct.

As stated above, the Act applies to any entity that carries on a business, or even part of a business, in the United Kingdom whether the acts or omissions, the constituent elements of the relevant offenses took place in the United Kingdom or elsewhere. The secretary of state’s guidance now indicates that mere listing on the London Stock Exchange is unlikely to constitute a sufficient connection with the United Kingdom, but investors can be sure that any trade in, from, or to the United Kingdom will be enough to be caught by the reach of this Act. This far-reaching territorial scope places the United Kingdom’s anti-bribery legislation on a par with the US Foreign Corrupt Practices Act and with the obligations under the OECD Convention, to which the United Kingdom is a signatory—but it goes further.

The legislation includes a number of risk management and mitigation approaches aimed at giving effect to the legislation.

Risk Assessment involves regular and comprehensive assessments of the nature and extent of the risks relating to bribery to which the organization is exposed. The organization should consider whether using external professionals may be appropriate in this regard. Transparency International offers a useful Self-Evaluation Tool on its website,2 which is intended to assist companies to evaluate their current anti-bribery provisions.

Key bribery risks include:

In a speech before the Act came into force, a representative of the Serious Fraud Office stated:

We also recognize that some companies have in the past chosen not to ask too many questions about how those doors are being opened by those intermediaries. Often either not conducting sufficient due diligence or ignoring clear and cogent warning signs. Under the Bribery Act, that simply won’t do.

Top-level commitment requires the establishment within the organization of a culture in which there is zero tolerance of bribery. Steps are taken to ensure that the organization’s policy to operate without bribery is clearly communicated both within and outside the organization.

Due diligence should cover all the parties to a business relationship, including the organization’s supply chain, agents and intermediaries, joint venturers and the like, for example so-called politically exposed persons where the proposed business relationship involves, or is linked to, a prominent public office holder. It should also extend to all the markets in which the organization does business.

Clear, practical, and accessible policies and procedures should include comprehensive and clear policy documentation, for example a clear prohibition on all forms of bribery, and guidance on making political or charitable contributions, and appropriate levels of bona fide hospitality or promotional expenses.

Bribery prevention procedures should be put in place; for example, modification of sales incentives to give credit for orders refused where bribery is suspected, or whistle-blowing procedures to be implemented.

Procedures might be implemented to deal with any incidents of bribery promptly, consistently, and appropriately. Transparency International states in its Guidance4 that:

To be effective, the Program should rely on employees and others to raise concerns and violations as early as possible. To this end, the enterprise should provide secure and accessible channels through which employees and others should feel able to raise concerns and report violations (“whistle-blowing”) in confidence and without risk of reprisal.

Effective implementation would involve an implementation strategy including, for example, who is responsible for implementation, how training is done, internal reporting of progress to top management, defined penalties for breaches of agreed policies and procedures. Bribery prevention training should be considered. External communication should be considered and a company might seek to publicize its anti-bribery credentials by posting information on its website.

The OECD Guidance recommends “periodic reviews of the ethics and compliance programs or measures, designed to evaluate and improve their effectiveness . . . taking into account relevant developments in the field, and evolving international industry standards.”5 This could include financial and auditing controls. The Ministry of Justice suggests that large organizations might consider periodically reporting the result of reviews to the audit committee or the board, who in turn might wish to make an independent assessment of the adequacy of anti-bribery policies, and disclose their findings and recommendations in the company’s annual report to shareholders. This is potentially good news for lawyers and anti-bribery consultants, but it significantly increases the cost burden on organizations. However, that cost burden has to be seen in the context of a potential investigation and prosecution. The consequences in the United States of an SEC investigation are well-documented: Companies tend to disclose fully and frankly and to fall on their swords, all in an effort to avoid the publicity and public shaming of SEC enforcement action. It remains to be seen whether such a culture will develop in UK companies investing in high-risk markets or sectors.

The guidance does not supersede preexisting guidance such as the FSA’s rules and principles for regulated financial sector firms, which remain in force. The DPP and the SFO are preparing joint guidance, and the Ministry of Justice has published its Quick Start Guide and wider guidance on the Act. However, the publications have an untested weight at law and, in any event, “guidance” can be no more than that: The real test will come when courts—judges and juries—hear factual scenarios and apply the law to real-life situations.

A comparison of the UK Bribery Act with the US Foreign Corrupt Practices Act (FCPA) supports the notion of the far-reaching nature and potentially wide application of the English legislation.

The US Foreign Corrupt Practices Act has long been in the vanguard in relation to the compliance and ethical conduct of international businesses. Following investigations by the Securities and Exchange Commission (SEC) in the mid-1970s, over 400 companies in the United States voluntarily admitted making questionable or illegal payments in excess of $300 million in corporate funds to foreign government officials, politicians, and political parties.

After the enactment of the FCPA in 1977, amendments followed in 1988 and 1998. The 1998 amendments were introduced to implement the 1997 Convention on Combating Bribery of Foreign Public Officials in International Business Transactions, which was negotiated under the auspices of the Organization for Economic Cooperation and Development (OECD); the expectation was that the other 32 signatories to the convention at the time would follow suit with similar legislation (see President Clinton’s presidential signing statement dated November 10, 1998).* The “prohibited foreign trade practices” anti-bribery provisions essentially make it unlawful to bribe (meaning to make a corrupt offer, payment, promise to pay, or authorization of payment of any money or anything of value: e.g. 15 U.S.C. §§ 78dd-1(a)) a foreign government official or foreign political party or party official (referred to in this article as a “foreign official”), whether directly or indirectly through other persons, in order to obtain or retain business. Depending on the type of conduct, the place where such conduct takes place, and the nationality or place of residence of the person concerned, the FCPA potentially applies to individuals, partnerships, and other forms of business association or organizations including trusts, companies, officers, directors, employees, or agents of a company and stockholders acting on behalf of a company.

The targets of the legislation may also be penalized if they order, authorize, or assist someone else to violate the anti-bribery provisions or if they conspire to violate those provisions.

Jurisdiction is not limited to conduct taking place in the United States in all cases. The provisions cover:

The definitions of domestic concerns and US person are wide ranging. The former is defined as an individual who is a citizen, national, or resident of the United States or any corporation, partnership, association, joint-stock company, business trust, unincorporated organization, or sole proprietorship that has its principal place of business in the United States, or that is organized under the laws of a state of the United States or a territory, possession, or commonwealth of the United States. A US person is defined as, for example, a US national or a corporation, partnership, association, joint-stock company, business trust, unincorporated organization, or sole proprietorship organized under the laws of the United States or any state, territory, possession, or commonwealth of the United States, or any political subdivision thereof.

Not all payments to foreign officials give rise to liability under the FCPA (for example, see the discussion in “Defenses”).

The scope of the UK Bribery Act 2010 is in some respects wider than that of the FCPA and it may come to be regarded as amounting to tougher anticorruption legislation, providing as it does for wider territorial effect, liability by omission, fewer defenses, and stiffer penalties. The details of the offenses created by the Act are set out elsewhere in this chapter. Now we deal, in summary, with some of the principal differences between the two pieces of legislation.

The FCPA applies to bribery of non-US government officials, political parties, and party officials. The Act is potentially engaged by bribery not only of non-UK public officials, but also of UK officials and private sector individuals, an important factor that will need to be borne in mind by US entities operating in the United Kingdom.

Under the FCPA, companies operating in the United States that do not issue securities in the United States or make securities filings with the SEC and are not domestic concerns can only be liable if the conduct relating to the bribery occurred in the United States.

The Bribery Act provides extraterritorial jurisdiction to prosecute offenses where the corrupt conduct occurred in the United Kingdom and where the conduct occurred outside the United Kingdom. In relation to the section 6 offense of bribery of foreign public officials, for example, this applies to conduct occurring wholly outside the United Kingdom where the conduct would have been an offense if carried out in the United Kingdom, provided the defendant has a close connection with the United Kingdom (essentially if the defendant is a UK national or UK overseas territories national, a UK resident, or a UK corporate body).

Under section 7, the Act has created a strict liability corporate offense of failure by a commercial organization to prevent bribery by a person associated with the organization, that is to say any person performing services for or on behalf of the organization. This offense applies to corporate bodies or partnerships incorporated in the United Kingdom or formed under the law of the United Kingdom, who are carrying on business in the United Kingdom or elsewhere; or any other corporate body or partnership carrying on business or part of a business in the United Kingdom.6 Provided at least one of these requirements is met, the commercial organization will be liable even if all the relevant conduct takes place outside the United Kingdom and has no connection with the United Kingdom.

Consequently, for a non-UK body that carries on only a part of its business in the United Kingdom, circumstances in which every aspect of the conduct relating to the bribe occurs outside the United Kingdom and where the commercial entity has done nothing more than fail to prevent the making of a bribe may still result in prosecution.

There is no similar offense under the FCPA to the Bribery Act offense of failing to prevent bribery, although it may be possible for a person to be liable where they have knowledge that a corrupt payment has been made on their behalf.

The United Kingdom legislation provides a defense to the section 7 offense when it can be shown that the organization had in place adequate procedures designed to prevent the bribery.7 Generally, adequate procedures will not provide a defense under the US legislation. However, it is one of many factors considered when deciding whether to bring a charge. It is included within the US sentencing guidelines as a mitigating feature.

There are three exceptions, or “affirmative defenses,” provided for under the FCPA, only one of which is reflected in the Act. They are:

Under the Act there is no defense for bona fide expenditure or facilitation expenditure. However, it would be a defense under the Act to the offense of bribing a foreign official if the foreign official were permitted by the written law applicable to him to be influenced by the offer, promise, or gift.8

The maximum penalties under the Act are more severe than the FCPA penalties—five years’ imprisonment under the latter and ten years under the former.

The United States has adopted a scheme of self-reporting, which it encourages, alongside internal investigations, in return for negotiation in plea agreements and reduced sanctions. There may be lesser penalties where the management of a company is changed before the misconduct came to light and in some cases no sanctions at all.9 This practice has been adopted by the Serious Fraud Office in the United Kingdom in other contexts.10

Prosecutions in the United States have affected companies and individuals in the United Kingdom. The US government is currently seeking the extradition of Jeffrey Tesler and Wojciech Chodan, both United Kingdom citizens who were indicted for their involvement in the Bonny Island, Nigeria bribery scheme. There have also been prosecutions in the United States of United Kingdom companies and of companies with a UK connection, including Mabey & Johnson in 2009, Aibel Group Ltd in 2008, and York International Corporation in 2007.

The FCPA was the long-time flag bearer for anti-corruption legislation, although it now appears that, through the Act, the United Kingdom is seeking a comparable international policing and enforcement role. It remains to be seen what the result of this new intervention will be. However, given the extraterritorial extent of the Act in certain circumstances and in particular its potential application to conduct wholly unconnected with the United Kingdom, foreign corporations carrying on even a small part of their business in the United Kingdom will need to review carefully their worldwide practices and procedures so as to attempt to ensure that, should a bribe be paid by someone performing services on their behalf anywhere in the world, they can rely on the adequate procedure defense.

Charles Brewer

NaMax DI Limited

The purpose of all business activity is profitable investment. This can only be reliably achieved through the implementation of sound plans and strategies which themselves can only be brought about through the conversion of analysis into practical action.

In all cases, this involves the analysis of data, and in today’s circumstances will involve the examination of data using information technology (IT), in particular software allied with ever-increasingly powerful hardware.

In this section, we explore the two critical components: the data and the tools available for its analysis. We also examine some of the critical differences that may occur in the circumstances of the analysis in developed and developing markets and seek to highlight some of the dangers of using methods appropriate for the former in the latter, in particular as regards the validation of “rolled up” data, and finally briefly review some suggestions for the use of information technology in the analysis of investment decisions in developing markets.

The section does not address, except in passing, the actual methods of analysis applied or their particular relevance to one case or another. Rather, it seeks to elucidate the data environment in which analysis takes place and how the different circumstances should condition the analysis. Above all, it does not address directly the skills and critical faculties of those carrying out the analysis, and on whom, ultimately, all responsibility must fall; a poor analyst may derive bad plans from perfect data, whereas a good one will be distinguished by extracting good decisions from flawed data.

This section seeks to elucidate the environment in which good and poor analysts actually work and their dependence on IT.

The objective of investment analysis is the evaluation of the probabilities of acceptable returns in the given circumstances of risk. The standard models for this invoke assessing the likelihood of a given outcome given both latitudinal (contemporaneous/similar company or market) and longitudinal (asynchronous/dissimilar company or market) comparison and ranking investment options prior to formulation and execution of plans. The term company should be taken as an abbreviation for company/market/country.

Data for investment decisions has a number of broad characteristics. We may roughly group these into two categories that we shall term quantitative and environmental. These should not be considered firm distinctions, for some of our quantitative measure may be little more than rankings or estimates, and some of our environmental factors may be susceptible to precise formulation, but in the broad sense, the qualitative factors relate to the actual constitutive qualities of the data, while the environmental factors primarily affect the manner in which the data should be regarded and treated. Each of the factors has constraints and may be seriously compromised if other factors are only weakly present.

Qualitative factors that relate to the constitutive qualities of the data comprise:

These are the factors that are normally considered as part of an analysis. In a developed economy, and for larger enterprises, these will normally be available in good measure. The regulatory returns, annual reports, and corporate analysts’ statements will generally give all the information necessary to conduct a sound standard analysis of the data and a ranking of likely risks and returns given whatever circumstances the analyst chooses to make use of in forecasting scenarios.

These are the lenses through which the more concrete qualitative factors are seen, and frequently are little more than an adjectival gloss on a standard analysis. However, these factors can have and should be considered to have a profound influence on how data should be interpreted.

Environmental factors can have a profound effect on any assessment based on the quantitative factors, even though we would normally place significantly more weight on the former in actually finalizing assessments of investment opportunities.

As any end-of-year review of the IT technical press will show, the volume of data held on computer networks is growing exponentially. A recent paper (Makarenko, 2011) suggests that as of 2012 there is approximately 3 zettabytes (3 × 270 bytes) of data stored globally, and that this will continue to grow in a non-linear manner for some time. To put this into perspective, in 2009, the entire Internet was estimated to contain 500 exabytes (500 billion GB) of data, which is half a zettabyte.

Of course, vast amounts of this data are images on Facebook, the result of particle collisions at CERN or copies of copies of copies of documents in Word, but it is certainly true that the longitudinal and latitudinal data held on financial and economic databases in immense and grows continuously.

It is now possible to obtain extensive, multiyear data on 6,548 companies listed on the three major New York exchanges and 9,021 listed in London. There are 2,823,554 companies and LLPs registered at Companies House London. For a single, randomly chosen company, in a single page, the Morningstar Report gives 503 items of summarized data (excluding attribute names and column headings) plus four pages of commentary. If we take into account the volumes of data in Bloomberg, Thomson Reuters, Zawya (Middle East), Quick (Japan), and others, the volume of data is enormous and certainly well beyond the capabilities of any individual to handle manually.

We next consider the main types of tool used for analysis. These fall into three main categories:

Excel is the dominant analytical software used.11 Close to all users use Excel in one form or another. Access and ACL are also frequently used by some 35 to 45 percent of users respectively. All other software is used by less than 20 percent of users.

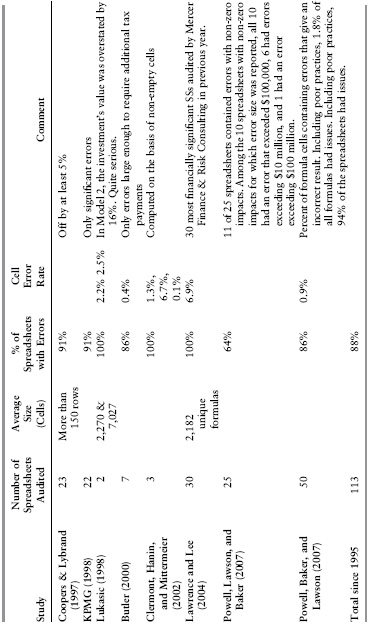

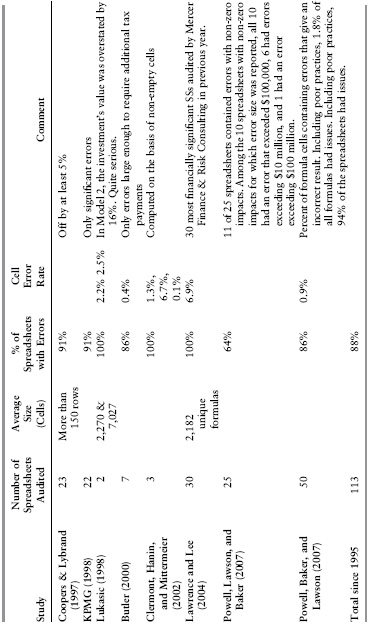

The most common method of analysis of data by far is the by means of spreadsheets, which for all practical purposes means Microsoft Excel and various add-ins which may be used to carry out more specialized functions than are normally available in the standard package. Accuracy in spreadsheets has been studied over a reasonably lengthy period, and studies over the years appear to confirm the profound risks that are common. Table 15.1 shows the findings of a meta-analysis carried out by Panko (1998, revised 2008), one of the leading researchers in the field, which shows that nearly all spreadsheets in business have material errors. Kruck (2001) and others have demonstrated that even under so-called ideal conditions (team development, spreadsheet review) errors are very common. Worryingly, some software vendors appear to make a virtue of their ability to incorporate spreadsheets into other models. For example, the insurance rating package DecisionMaker Rating “facilitates the rating development cycle by allowing automated rating and underwriting services to be built from existing Excel™ spreadsheet models.”* This may not be considered an unqualified virtue or benefit.

TABLE 15.1 Spreadsheet Errors

Source: Adapted from (Panko, 1998, revised 2008).

A wide range of tools exists, ranging from the relatively generic (Crystal Reports, Microsoft Access) to the more sophisticated (Oracle Financials, IBM COGNOS) to the specialized (ACL, SAS, SPSS). These are typically used to extract data from operational sources, such as accounting and production systems, and to carry out standard functions on the data.

The two main drawbacks for software of this nature for use in data analysis are the time and effort required for collection and preparation of data and the general inability to deal with defective data.

Extraction and preparation of data for these systems is often a major effort, and often the analytical tools themselves will have expectations as to the content and format of data to be processed. In most cases, data sources need to be analyzed and converted into data cubes before any real analysis can be done.

This has two major drawbacks for data in developing markets: First, data deficiencies (missing or erroneous data) will not be highlighted but will be subsumed in the mass of information and tend to lose those features that might alert an expert analyst. Second, the analytical elements of the systems will tend to have certain expectations as to relevance and comparability of data that may not be fulfilled (or may only be fulfilled by indirect analysis of the data).

This is software that has few or no preconceptions about the data to be analyzed. Wickham (Wickam, 2009) describes a grammar of graphics such that “a statistical graphic is a mapping from data to aesthetic attributes (color, shape, size) of geometrical objects (points, lines, bars).” the important aspect being the relative success of the aesthetic element to depict, represent, or highlight some aspect of the data which would otherwise be obscured or lost.

Data mining is the process of iterative search and analysis where both the search and the result will tend to be informative. The mere act of investigation, even if it does not lead to interesting answers, will tend to make the investigator more informed and hence more generally understanding of situations.

Data mining is often carried out with highly technical software such as SAS or SPSS, both of which require significant effort both to use and to interpret, and are sometimes limited in terms of the forms of output available. More modern tools, such as Tableau, Qlikview, and Mosaic, place more emphasis on the interaction between mining and visualization and the ability to modify or add new attributes and values to give “what if” and other data modifications.

The weaknesses of these types of software to some degree match those of the other categories: They may require significant data preparation, or have difficulty handling large volumes, but overall are well-suited to the analysis of non-standard data forms.

It is often said by business managers or frustrated analysts that there is not enough information available, but this is almost the exact opposite of the truth; we have moved from a world where data was indeed sparse to one where it is superabundant. What has failed to keep pace is the ability to manage, access, process, and present the data in a comprehensible and relevant manner.

However, in developing markets, it will often be the case that the data available fails to conform to one or more of the desirable characteristics and that we must apply compensating factors in order to be able to carry out our investigation. Table 15.2 shows some tactical approaches for this.

TABLE 15.2 Comparison of Data Usage Issues: Developed and Developing Economies

| Developed Market | Developing Market | Correcting Action |

| Latitudinal data: Covers all activities in detail | Covers some activities | Identify missing data Use proxies from similar entities |

| Longitudinal data: 5+ years | Limited or no time series | Extrapolate from similar markets/companies |

| Consistently used terms between companies and over time | Non-standard terminology or categorization | Go back to source data and recompile using preferred attributes |

| Comparable data, e.g., standard calendar | Non-comparable data: e.g., non-standard calendar (e.g., effect of Ramadan on year-on-year results/unusual holiday or political events) | Create new attributes categorizing information appropriately |

| Integrated/consolidated books | Separate books for different entities/activities | Apply ETL and data dictionary to standardize. Apply bottom to top reconciliation |

| Audited data | Erroneous data | Apply reasonability rules |

| Complete data | Missing data | Proxies or extrapolation |

| Deceptive data | Apply delusive data rules |

Each of these involves a measure of modification of the original data in order for it to be properly susceptible to analysis and comparison. Furthermore, it is important to take note of the degree to which data has been modified and substituted. The importance of the expertise of the analyst is heightened rather than diminished by rendering the data more capable of comparison.

To allow for the differences between the regular data of developed markets and the less formally based data of developing markets a variety of tasks will therefore need to be undertaken. These will include:

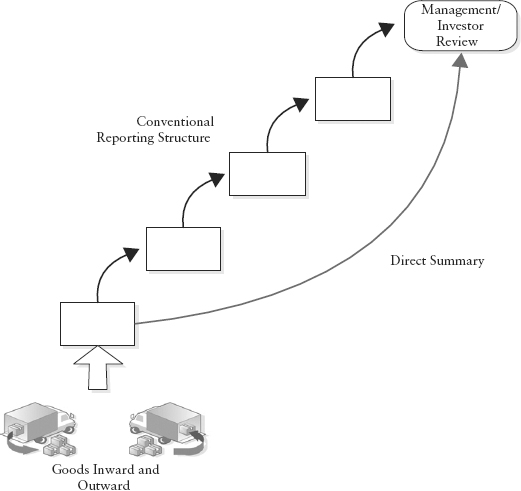

A particular issue may arise where there are multiple loosely integrated systems in which information is subject to potential or actual intervention. In many environments, there is a tendency to avoid presenting difficult news, and managers at various levels may intervene in data which is being passed upward. An account where payment is overdue may be “smoothed” to show overdue payments as less problematic than they are; for example, an invoice 130 days overdue may be included as a probable future revenue, when in fact it should probably be regarded as a loss for practical purposes.

The situation is portrayed in Figure 15.1.

FIGURE 15.1 Reporting Structures

A potential investor would do well to see whether it is possible to make use of very low-level data and examine a consolidated version of this rather than take the over-sanitized versions that may be presented through the normal management reporting route. Such an approach is often difficult, but some modern investigative tools exist that allow this.

Data is the key to sound analysis in all markets and all situations, and this is no less true in markets where the data is less available or presented in non-standard ways. The role of information technology in assisting the quality review of data and presenting it in an enlightening way is the first, and in some ways, the most critical step in allowing the investment analyst to assess whether an investment should or should not be made.

Developing market data in particular requires the analyst to be able to take a broad view of the available data, to be able to modify given data, and to be able automatically to apply rules to make the data susceptible to intelligent, accurate, and insightful analysis.

1. Available at www.justice.gov.uk/downloads/legislation/bribery-act-2010-guidance.pdf.

3. Ibid.

4. “Business Principles for Countering Bribery,” www.transparency.org.

5. “Good Practice Guidance on Internal Controls, Ethics, and Compliance,” February 18, 2010, OECD. www.oecd.org.

6. Act s7(5).

7. Act s7(2).

8. Act s6(3)(b).

9. See publications by law firm Bristows and others.

10. UK actions against Mabey & Johnson and ActE Systems.

11. IIA, The Institute of Internal Auditors, 2006, www.acl.com/pdfs/iia_survey_summary.pdf.

* Available online at http://www.presidency.ucsb.edu/ws/index.php?pid=55254