CHAPTER 5

Solstice Rites in the Americas

AS WE HAVE JUST SEEN, the ancient inhabitants of Europe and the Near East built spectacular passage chambers, stone circles, temples, and pyramids to mark ceremonially the Solstices and Equinoxes; half a world away, the indigenous peoples of the Americas had no less passionate an interest in the Sun’s seasonal cycle. Indeed, for some Native American tribes, the Solstices and Equinoxes served as the temporal cornerstones of culture.

The first people to arrive in the Americas probably came from Asia, perhaps forty thousand years ago (though there is still much controversy about this date among archaeologists). Since Siberian archaeological sites dating to the end of the last Ice Age show signs that the inhabitants kept a lunar calendar,1 we may assume that early migrants to North America brought with them an already developed concern for times and seasons. This assumption is supported somewhat by the existence of tally marks engraved on rock, found from Oregon to Mexico and as far east as central Nevada, reminiscent of the Paleolithic bone and ivory calendar notations studied by Alexander Marshack. The American petroglyphs appear to be several thousand years old, but unfortunately there is presently no way to date them precisely, since the radiocarbon method works only with organic materials.

However, if we use the basic worldview of surviving Native American peoples as a starting point, we can perform a sort of mythological archaeology that may help us to gain more insight into the thinking of their ancestors several millennia back in time. Two elements common to all North American tribal traditions are a regard for the sacred significance of the four directions of space, and a belief in the existence of a supernatural world—described everywhere in similar celestial imagery—that can be accessed through dreams or visions. Since these ideas are to be found among tribes that are geographically remote and that have dissimilar languages and customs, it seems likely that they were already part of the mythology of the hunters and gatherers who crossed the land bridge from Siberia many millennia ago.

In addition to the two core beliefs mentioned above, many tribes viewed the Solstices and Equinoxes as the temporal equivalents of the four sacred directions and as times when the supernatural world and the mundane world intersect.

About three thousand years ago the people who lived in the valley of the Mississippi and its tributaries began the construction of thousands of earthworks ranging in size from small heaps no bigger than a grave to platforms covering many acres. Some of the more impressive of these mounds were precisely geometrical in shape; others were fashioned in the forms of reptiles, birds, and other animals. While in recent times farmers have destroyed some of these earthworks, and many others that survive await detailed investigation, it is clear that the people who made them commonly oriented these earthen structures astronomically—often to the Solstice and Equinox sunrise points.

The mounds of the Mississippi Valley seem to have been produced throughout a period of over two thousand years by three distinct groups. The first are known as the Adena (we do not know what these people called themselves; as is standard practice in archaeology, they have been given the name of an excavated site), who left behind some of the most intriguing mounds—animal-shaped structures such as the Great Serpent Mound in Adams County, Ohio. After a few centuries, the Adena were gradually supplanted by the Hopewell, who built mounds in the forms of squares, circles, octagons, and straight lines. Last came the Mississippians, who flourished after 1000 C.E. and constructed massive pyramidal platform mounds. The Native Americans of the Mississippi Valley were still using these mounds for ceremonial purposes when Europeans first began colonizing the Americas.

A reconstruction of Cahokia. or Monk’s Mound.

Cahokia, near East St. Louis in southern Illinois, is the most elaborate and best-studied of the Mississippian sites. It was a city of several thousand that flourished between about 800 C.E. and 1550. Built around a ceremonial center of earthen pyramids, Cahokia originally encompassed over a hundred mounds, about eighty of which survive. Monk’s Mound, the largest of the complex, is one hundred feet high and sixteen acres in extent. Like others in the complex, it is oriented east-west, toward the equinoctial sunrise.

About a half mile west of Monk’s Mound, archaeologists working in the early 1960s found four large circles of post holes. Warren Wittry of the Cranbrook Institute of Science investigated one of these circles in detail and found that it incorporated precise Solstice alignments. Originally, the circle (which Wittry dubbed the “American Woodhenge”) consisted of wooden posts two feet wide, set four feet deep; the circle was 410 feet in diameter. Using a backsight post five feet east of the circle’s center, the builders sited posts to align with the summer and winter Solstice sunrise points; two other posts align with due east (the equinoctial sunrise) and north. Only about half of the circle is intact, however, so that it was impossible to determine if Solstice sunset points and other astronomical alignments were incorporated into the structure. The size of the circle and the precision of the posthole placement made the Cahokia Woodhenge an accurate calendar, probably used for the determination of seasonal ceremonies and festivals associated with planting.

The nomadic, hunting-and-gathering peoples of the Great Plains had a less complex society than the agricultural Mississippian moundbuilders, whose civilization was apparently influenced by those of Central America; yet the Plains Indians, too, paid close attention to seasons and cycles.

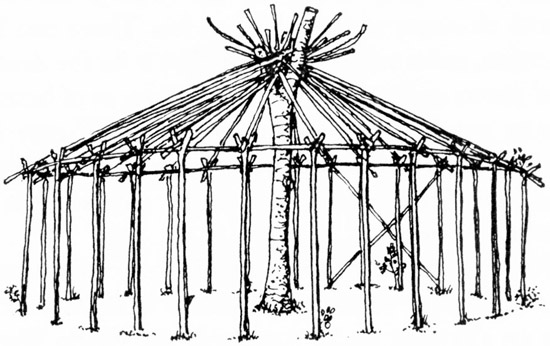

A few tribes, such as the Skidi Pawnee, though they maintained elaborate traditions concerning the stars and timed their ceremonies according to the seasonal motions of the constellations, seem to have had little interest in the Solstices. Nevertheless, most of the tribes from Texas to Canada, from the Mississippi to the Rockies—and particularly the Sioux Nation—participated in a common ceremonial, the Sun Dance, which was traditionally held at the time of the full Moon closest to the summer Solstice. On these yearly occasions, the people camped in a circle around a central cottonwood tree—the Sun Pole. They also built a circular Sun Dance Lodge of twenty-eight poles, with a pole at the center representing Wakan-Tanka, the Center of everything. Its entrance was to the east, toward the Equinox sunrise. The entire ceremony was sixteen days in length—eight days of preparation, four days of performance, and four days of abstinence. It was a time of renewal, healing, purification, and prayer. The people’s purpose in enacting the Sun Dance was to renew themselves and their world. The timing of the rite—near Midsummer, when the Sun is highest in the sky and the days are longest—was all-important.

The Sun Dance lodge. (After j. E. Brown)

Thomas Mails, a Lutheran pastor who has written extensively about Native American spiritual traditions, describes the climax of the ceremony:

When the Sun Dance is done properly, on the last day—and sometimes on one or more of the other days—each of the men called “pledgers” is pierced by having two wooden skewers (or sometimes eagle claws) inserted under the skin of their chests. These skewers are then attached to a strong rope and the other end tied to the Sun Pole. Then the men form a circle around the Sun Pole and, after going forward four times to lay their hands on it and pray, pull back as hard as they are able until the skewers are at last torn free. An alternative method is to have two of the skewers inserted under the skin of the back at shoulder blade height. Heavy buffalo skulls are hung by thongs from these and then dragged around by the bearer until their weight tears the skewers loose.2

It is difficult for modern civilized people to understand the ceremonial significance of pain and self-sacrifice within the context of the Native cultures. European-Americans tend to deny or avoid suffering and death at all costs; for the Indians, however, these were essential elements of the wheel of life. There can be no life without sacrifice, pain, and death—whether it be the death of food animals and plants so that the people may live, or of human beings so that future generations and the cosmos itself may live. The Sun Dance provided a focused opportunity for thanksgiving and renewal, and the flesh sacrifice it entailed ensured that it would never be taken lightly.

The Witchita Indians of Kansas built their villages around so-called council circles, which consisted of a central mound surrounded by an elliptical ditch. Archaeologist Waldo Wedel of the Smithsonian Institution investigated three of these circles in Rice County in 1967. He found that they had been built within sight of one another, about a mile apart, and that the lines of sight joining them were aligned with the summer Solstice sunrise and the winter Solstice sunset. He noted also that one of the circles, the Hayes, had its major axis directed toward summer Solstice sunrise; the axis of another, the Tobias circle, was directed toward the summer Solstice sunset.

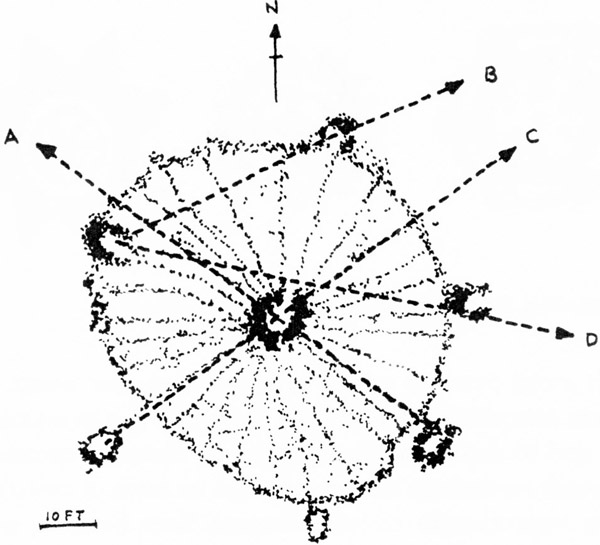

Further to the west, along the eastern slope of the Rocky Mountains and ranging from Colorado north into Canada, lie the remains of about fifty stone circles known as medicine wheels. Each is composed of small rocks and is centered on a large cairn, or rock pile. Most of the wheels are spoked, and in many cases the spokes are astronomically oriented. The best-studied of these circles are the Bighorn Medicine Wheel on Medicine Mountain near Sheridan, Wyoming, which embodies summer Solstice sunrise and sunset, as well as two stellar alignments; the Fort Smith Medicine Wheel on the Crow Indian Reservation in southern Montana, whose longest spoke points toward Midsummer sunrise; and the Moose Mountain Medicine Wheel in Saskatchewan, which marks the same celestial events as the Bighorn wheel. The Bighorn Medicine Wheel has twenty-eight spokes, the number of poles in the traditional Sun Dance lodge.

The medicine wheels are difficult to date, and it has so far proven difficult to determine who built them or how they were used. It seems likely, however, that they were involved in seasonal rites similar to the Sun Dance—at which people from hundreds of miles around gathered for several days of celebration, ceremony, and prayers to the Above Beings.

The Bighorn Medicine Wheel in Wyoming. The alignments indicated are: A. Summer Solstice sunset; B. Aldebaran rises; C. Summer Solstice sunrise; and D. Rigel rises.

The Chumash Indians of the central Pacific coast of California saw the Solstices as times when the Earth, human society, and the Cosmos all reached points of crisis. On these occasions, the survival of the world depended upon the people’s performance of appropriate ceremonies.

Perhaps because their food source was abundant, the Chumash occupied permanent settlements (unlike most other hunter-gatherers) and developed a complex and stratified society. At the time of first contact with Europeans, in 1542, they were organized into two provinces, one ruled by a woman. At the top of the Chumash social pyramid were a religious elite, the ‘antap, among whom were astronomer-shamans whose duty it was to maintain the calendar and to determine the appropriate times for ceremonies.

Sun symbols from various Chumash rock paintings.

Chumash mythology centered on the motions of celestial bodies. These were thought to have formerly been humans, who had ascended from the Earth long ago to escape from a world catastrophe—the primeval flood described in so many cultures’ traditions. The most important and powerful of the sky beings was the Sun, who lived in a quartz crystal house. The Sun was believed to lead a team of sky people in an ongoing daily ball game in which the opposing team was led by Sky Coyote (the North Star), whom the people viewed as their benefactor. Moon kept score. The game was concluded each year at winter Solstice, when there was a real danger that the Sun’s team might win and decide not to return, thus upsetting the balance of nature.

For the Chumash, the Solstices were revelations of the cosmic order. The people themselves ritually participated in that order by helping to restore the Moon to life each month through their prayers and shouts, and by averting cosmic catastrophe each Midwinter. The astronomer-shaman, the ‘alchuklash, played a key role in the latter drama by maintaining a vigil in a special Sun-watching cave, and alerting his people of the arrival of the Solstice. When the time came, several days of ceremonies ensued, presided over by the high chief, the paha, who was considered the “Image of the Sun.” Also during this time shamans consumed the sacred psychedelic herb datura, and the people participated in dances symbolizing the soul’s journey along the Milky Way to the land of the dead.

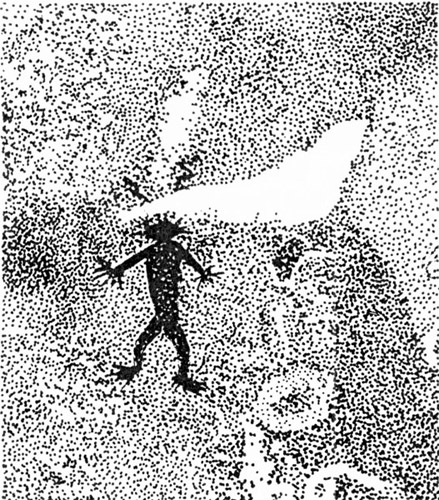

The Chumash produced some of the finest rock art in North America, much of which centered on the mythic significance of the Solstice. At many cave sites in the region between modern Los Angeles and Santa Barbara, spotlighting effects have been observed on Midwinter morning. For example, at Burro Flats, just beyond the northeast corner of San Fernando Valley, a complex collection of animal and geometric images is shaded throughout the year by a canopy of rock; then, on the morning of the winter Solstice, a triangle of sunlight cuts to the center of a series of concentric rings before shrinking back to the base of the prepared rock surface Similar effects have been observed at Condor Cave in the Los Padres National Forest, at Window Cave at Vandenberg Air Force Base, and at La Rumorosa in Baja, where a dagger of sunlight illuminates a white circle, then cuts precisely across the eyes of a thirteen-inch high shaman figure, as if to symbolize his magical participation in the event.

Other West Coast tribes, from present-day Baja to British Columbia, shared a similar concern for the Solstices. For example, further north in California—in Sonoma and Mendocino counties—the Porno Indians called the Solstices the times of “starting back.” Each valley was watched by a special Sun priest who noted the position of sunrise each day in relation to a particular hill on the horizon, and thereby kept track of the Sun’s progress toward a Solstice. When sunrise occurred in the same spot for four consecutive days, the sunwatcher proclaimed the Solstice.

Late in the morning of June 29, 1977, Anna Sofaer, an artist with an interest in prehistoric Indian petroglyphs, made a treacherous 430-foot climb to the top of Fajada Butte in Chaco Canyon in New Mexico to photograph two spirals carved high on the butte’s eastern face. The carvings were shaded by three large, parallel slabs of rock. But as Sofaer knelt to capture the carvings on film, she noticed a thin dagger of sunlight moving vertically down the large: spiral, just to the right of its center. The timing of her arrival at the site turned out to have been all-important: it was noon and, as she then realized, only a few days past Midsummer. As she later told an audience at the Los Alamos Laboratory, “it occurred to me that the spiral was put there to record [the Solstice]. A week earlier the light would have passed through the center. It was an incredible coincidence that I was there just a few days past the summer Solstice, at noon. If I had come a little later or earlier [in the day], I would have missed the whole thing.”3

The figure of a shaman, painted in red, on the wall of La Rumorosa, a rock shelter in Baja California. On the winter Solstice, a triangle of light crosses the shaman’s face.

The next year, Sofaer returned to Fajada Butte, accompanied by physicist Rolf M. Sinclair and Volker Zinser, an architect familiar with spotlighting effects. Beginning in mid-May, they recorded the play of sunlight across the two spirals and studied the rock surfaces that shaped the sliver of light. On June 21, the sunbeam moved precisely through the center of the larger spiral. But they noticed a much smaller, second spot of sunlight to the left. Could it have a function as well, they wondered? They returned at the fall Equinox, and found that now one of the light beams bisected the smaller spiral (the same effect occurs at the spring Equinox); and when they returned yet again at the winter Solstice, they observed the two streaks of light framing the larger spiral. Here, in a single stone structure, ancient astronomers had found a way to mark each of the Solstices and Equinoxes with a unique spotlighting effect.

The light and shadow effect on the petroglyphs at Fajada Butte in Chaco Canyon. Left: winter Solstice; center the Equinoxes; right: summer Solstice.

Sofaer and Zinser became convinced, for a variety of reasons, that the rock slabs were deliberately positioned and carefully shaped in order to produce the lighting effects. A later geological survey cast doubt on the idea that the native astronomers had in fact moved the slabs into place; even so, they had clearly taken masterful advantage of the situation. “The monumental quality of this solar construct,” wrote Kendrick Frazier in Science News, “…is characterized by the Indians’ sensitive integration of their structures with nature, light, and patterns of the solar cycle.”4

Chaco Canyon is the largest of hundreds of ruins throughout the American Southwest that are attributed to the Anasazi, a Navajo word for “the ancient ones,” who, according to some experts, were the ancestors of the modern Hopi and Zuni Indians. Their complex and widespread culture flourished between 400 and 1300 C.E., when it apparently succumbed—as have so many civilizations—to the exhaustion of local environmental resources. The Anasazi built a remarkable series of roads and ceremonial centers, but apparently did not have an oppressive social hierarchy or wealthy ruling class. While the Anasazi had no system of writing by which to record their spiritual beliefs, their ruins offer direct evidence of these people’s profound interest in the Sun’s seasonal journey.

Casa Rinconada, a kiva (or underground circular ceremonial chamber), and Casa Bonita, an Anasazi town that once housed perhaps six thousand people, are located not far from Fajada Butte in Chaco Canyon National Monument. Casa Rinconada has a wall niche that is illuminated by the Sun at summer Solstice sunrise, and the corner windows of Pueblo Bonito permitted observation of the winter Solstice sunrise. At another site, in Hovenweep National Monument in the Four Corners region, archaeoastronomer Dr. Ray Williamson has studied a solar shrine that, like the one at Fajada, was used to track both the Solstices and the Equinoxes. It consists of two small, angled windows in an otherwise gloomy room on the ground floor of a fortress-like ruin. The windows are so placed that at Midwinter sunset the Sun appears through one window and casts a beam on the far wall; at Midsummer it appears through the other window; and at the Equinoxes two sunbeams can be seen, each lined up with one of the low doorways by which the room is accessed.

Since the Anasazi left no writings, we can only speculate about the nature of their Solstice celebrations. But the Anasazi’s present-day descendants, the Zuni and Hopi Indians, have astronomically-based rites that may, in their general outlines at least, date back many centuries to the time when Chaco Canyon was a thriving cultural center.

For the Zuni, the winter Solstice is the time of the Shalako, an elaborate night-long ceremony—still performed today and observed by thousands of tourists—that includes appearances by the Katchina priest and clowns and the Shalako themselves—twelve-foot-high bird-headed effigies regarded as messengers from the gods. The timing of the rite is all-important, and in former days it was entrusted to the Pekwin, or Sun Priest. It was his task to ensure that the Shalako ceremony coincided as closely as possible with both itiwanna, the exact day of the winter Solstice, and also the full Moon.

The Pekwin observed the Sun at dawn and sunset by watching its place of appearance or disappearance on the horizon from fixed viewing points—a petrified stump at the edge of the village, a “Sun tower,” or a small, semicircular stone shrine. Before both the summer and winter Solstice, the Sun Priest traditionally undertook eight days of ritual prayer and fasting, during which he made pilgrimages to the sacred Thunder Mountain and communed with the Sun Father. On the ninth morning, he announced the approach of the Solstice with a call that was, as ethnologist Frank Cushing described it in the 1880s, “low, mournful, yet strangely penetrating and tuneful.”

But the Pekwin had no monopoly on the observation of the solar cycle. Cushing noted that

…many are the houses in Zuni with scores on their walls or ancient plates imbedded therein, while opposite a convenient window or small port-hole lets in the light of the rising sun, which shines but two mornings in three hundred and sixty-five on the same place. Wonderfully reliable and ingenious are these rude systems of orientation by which the religion, the labors and even the pastimes of the Zunis are regulated.5

The Hopi Sun Chief had duties similar to those of the Zuni Pekwin. During the winter, he would sit on the roof of the Sun Clan house in the village of Walpi and from there watch the Sun set over the distant San Francisco mountains. When it reached a dip beside the southernmost peak, he proclaimed the time for the night-long Solstice ceremony of the kindling of fire.

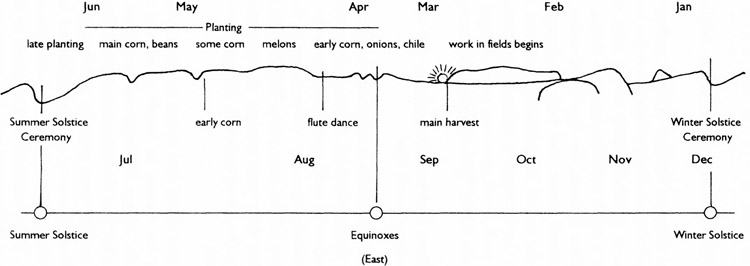

The Hopi sunwatcher was not only concerned with the Solstices, however. The planting of crops, as well as the timing of the year-long cycle of Hopi ceremonies, was tied to the position of the Sun. In his 1931 paper on “The Hopi Ceremonial Calendar” in the Museum Notes of the Museum of Northern Arizona, Edmund N. Nequatewa wrote:

The Hopi horizon calendar.

The cycle of Hopi ceremonies begins in the winter. The dates of all the winter ceremonies are established by watching the position of the sun as it sets on the western horizon, while those of the summer ceremonies are fixed by the position of the rising sun on the eastern horizon.…

The first of the winter ceremonies is in November. When the sun sets over a particular hump on the north side of the San Francisco Peaks, the ceremony, Wu-Wu-che-ma, takes place. Four societies take part.…

After this ceremony is over, they again watch the sun on the western horizon. They just know on a certain day that it will take the sun eight days to reach its southernmost point, and they announce the ceremony for eight days ahead. Thus, Sol-ya-lang-eu, the Prayer-Offering Ceremony, is the Winter Solstice Ceremony, and takes place in December. This is one of the most sacred ceremonies of the Hopi. It is a day of good will, when every man wishes for prosperity and health, for his family and friends.…6

Just after the summer Solstice, the Hopi celebrate a festival they call Niman Kachina. It is the time when the kachinas—the spirits of the invisible forces of life—return home to the the spiritworld. When it is the summer Solstice in this Earth, it is winter Solstice in the lower world, and in this way balance is maintained in the universe. The Niman Kachina celebration is focused on a ceremony of the four energies—the germination of plants, the heat of the Sun, the life-giving qualities of water, and the magnetic forces in the Earth and atmosphere. The Hopi use spruce branches in the ceremony because these are believed to have a magnetic force that draws rain.

In their precise observations of the Sun’s stations, the Hopi, the Zuni, and presumably the Anasazi were not motivated by the desire for scientific knowledge. Their calendars were not attempts to objectify time in the familiar (to us) categories of past, present, and future, but were rather mythological and ritual constructs. These peoples were driven by an overwhelming concern for being “in tune” with cosmic cycles. The Hopi see everything in nature in terms of complementary principles—life and death, summer and winter, day and night. It is their duty, they believe, to maintain the balance of the forces of nature and cosmos through ritual activity The Solstices and Equinoxes are special opportunities for human beings to celebrate and reinforce that balance.

An hour’s drive northeast of Mexico City lie the restored ruins of Teotihuacan, the largest city of pre-Columbian America and a source of continuing mystery for archaeologists. We still do not know who built the city, what language the builders spoke, or where they went after it was destroyed.

At its height, Teotihuacan’s population reached 170,000 or more—Comparable with that of Imperial Rome. The city’s construction was begun around 200 B.C.E., according to most archaeologists (though a few suggest much earlier dates), and around 100 C.E. work commenced on two enormous pyramids. The larger of these, the Pyramid of the Sun, covers about the same land area as the Great Pyramid of Gizeh, though it rises to about half the latter structure’s height, or just over two hundred feet. In the years after 250 C.E., Teotihuacan’s influence spread throughout Mesoamerica, and other cities were modelled after it. Around 750, however, it was destroyed by fire and abandoned, perhaps as the result of invasion or a natural catastrophe.

Teotihuacan was laid out according to a strict right-angle grid pattern. This prodigious feat of surveying was accomplished with the help of numerous cross-and-circle markers chipped into rock surfaces and temple floors throughout the surrounding region. But the axis of the city’s streets, temples, public baths, ball courts, theaters, and apartment houses is about sixteen degrees askew of the cardinal directions. Why this peculiar orientation?

The answer seems to lie in an alignment at right angles to the main avenue of the city. In the first and second centuries of the common era, the Pleiades set just before dawn at the western horizon point marked by the alignment on the morning of the one day of the year when (at this latitude) the Sun shines directly overhead, casting no shadows. This “zenith day” occurs on the Equinoxes at the equator, and at the summer Solstice at the tropic of Cancer and the Tropic of Capricorn. Between the equator and the tropic lines, the date varies according to latitude; north or south of the tropics, there is no zenith day. The phenomenon of the shadowless noon is a striking one, and virtually all Central American cultures accorded it great significance. But at Teotihuacan, this solar event was compounded with a stellar one: on the night before the shadowless day, the Pleiades passed through the zenith at about midnight, when the Sun was at anti-zenith. Then, as the Pleiades set in the west, the Sun rose in the east; and when the Sun reached zenith at noon, the Pleiades were in turn directly underfoot at anti-zenith, metaphorically in the underworld. The Sun and the Pleiades may therefore have served to represent to the Teotihuacans the universal complementary principles of light and dark, life and death, this world and the next.

The Street of the Dead in Teotihuacan is precisely perpendicular to a line joining two pecked crosses. That line points to the place on the horizon where the Sun rises on the summer Solstice.

There is evidence that the builders of Teotihuacan were so concerned with the zenith day that they sought to establish the location of the Tropic of Cancer. Less than three miles north of the line of the Tropic, Charles Kelley of the University of Southern Illinois found more cross-and-circle symbols almost identical to the ones at Teotihuacan; their axes point to the place on the horizon where the Sun rises at Midsummer, the day it also passes through the zenith at noon at the Tropic.

The Pyramid of the Sun, meanwhile, served as an Equinox indicator. The lower part of the pyramid’s fourth level is boldly outlined and visible for miles; it is so angled that during the morning on the Equinoxes it is in shadow, but just at noon local time the Sun’s rays reach it. Then, two days after the Equinox the shadow on the north face “flashes” on and off at midday. The knowledge and skill required of the architects in order to produce these effects must have been considerable.

In his 1976 book Mysteries of the Mexican Pyramids, Peter Tompkins traced the history of the exploration of Teotihuacan and summarized over two centuries of speculations about its builders identity, purposes, and abilities, presenting at some length the views of Hugh Harleston, Jr., an American engineer who became fascinated with the ruined city and spent years analyzing its astronomical and geodetic functions. Harleston theorized both that Teotihuacan was built around units of measure identical with those used in the ancient Near East (as in the Great Pyramid), and that the designers incorporated into their ceremonial structures significant numbers relating to the dimensions of the Earth, the orbital distances of the planets, etc. In Harleston’s view, the city was meant to serve (among other things) as an accurate map of the heavens. Harleston located numerous sight-lines joining temples and pyramids throughout the city, by which the summer and winter Solstices and the Equinoxes might have been marked.

The people of Teotihuacan, like those of other Central American civilizations, no doubt saw the lights in the sky as representing a cosmic hierarchy of divine beings; the kings and nobles of the terrestrial world were their appointed representatives, and human events like wars and natural disasters were seen as reflections of confrontations between and among the cosmic powers. By organizing their city according to a celestial design, and by enacting ceremonies at cosmically significant times (such as the Solstices and Equinoxes), the people of Teotihuacan sought to establish and maintain precarious balances between order and chaos, freedom and security—balances that every civilization strives for, but that few are able to keep for long.

To the south of Teotihuacan lived the Mayas, whose high culture flourished in the present-day Mexican states of Chiapas, Tabasco, Yucatan, and Campeche, the Mexican territory of Quintana Roo, as well as in Guatemala and Belize and parts of Honduras and El Salvador. We know that Mayan civilization ended about 900 C.E., when it gradually succumbed, perhaps to political disintegration and the invasions of nomadic tribes. Its beginnings are less certain, however, and keep getting pushed back in time by archaeologists (the current estimate is something like 2500 B.C.E.). Like the people of Teotihuacan, the Mayas were prodigious builders and sophisticated astronomers. Indeed, their knowledge of the sky was as detailed and accurate as that of any ancient people whose works have survived and been deciphered.

The Toltecs, who conquered the Mayan city of Chichén Itzá and presided over a cultural renaissance there until shortly after 1200, had an annual solar calendar fixed at 365 days with a leap year every fourth year. The Classic Maya, in contrast, used the day as their fundamental unit of time. Their sophisticated arithmetic, by which they computed dates in the millions of days, incorporated place-value notation and the concept of zero. Using the day-unit, the Maya synchronized lunar months, solar years, planetary phases, eclipses, and other celestial phenomena, and correlated them with the events of their own political history. They thereby became the first people in the world to integrate celestial and terrestrial time in a single, comprehensive system.

Like the Babylonians, the Maya held an attitude toward time, astronomy, and mathematics that was not so much scientific (in the modern sense) as astrological. All their observations were regarded as omens for rulers and their families; their elaborate computations represented an obsessive search for a system of numbers that would encompass both the motions of celestial bodies and the events of human history in a unified scheme capable of foretelling the fortunes of a wealthy elite.

The temple group at Uaxactun, as viewed from the steps of Pyramid of Group E. The Equinox sunrise appears over the center temple; the summer Solstice sunrise appears at the corner of the left temple, and the winter Solstice sunrise at the corner of the right temple. (After Krupp)

The Solstice and Equinox alignments from the pyramid of Group E at Uaxactun.

Solar alignments have been found at many Mayan sites. One of the most remarkable examples consists of a group of temples at Uaxactun, a ceremonial center in the Guatemalan jungle. If one stands at the top step of the western pyramid and faces east, sunrise occurs over three small, equally-spaced buildings on a great stone platform. The placement of the northern and southern buildings permits accurate determination of the Solstices; on the Equinoxes, the Sun rises immediately above the central temple. This alignment scheme was copied in at least a dozen other Mayan cities.

An even more intriguing set of orientations was incorporated into a tower at Chichén Itzá. Known as the Caracol because of an inner spiral stairway (caracol being Spanish for “snail”), the structure seems to have been used as a multipurpose observatory. Nearly all the walls, doors, and windows of the Caracol are asymmetrically situated. But, using them as sighting lines, it is possible to mark the Solstices and Equinoxes, as well as the rising or setting points of several bright stars and the planet Venus.

Our understanding of the Maya’s astronomy is greatly facilitated by the fact that theirs was a literate civilization. In addition to their temples and observatories we have a few surviving writings in native Mayan which record that people’s mythology and worldview (though most such writings were tragically burned by the Inquisition). Among these is a book from the colonial period that is traditionally attributed to Chilam Balam, a legendary sage and scholar. In a section on Mayan astronomical knowledge and practice it is recorded:

When the eleventh day of June shall come, it will be the longest day, when the thirteenth of September comes, this day and night are precisely the same length. When the twelfth day of December shall come, the day is short, but the night is long. When the tenth day of March comes, the day and the night will be equal in length.7

The translator, Ralph Roys, notes that “This date for the summer Solstice indicates that the passage was originally written at a time when the Julian calendar was still current in the Yucatan.”

The ruins of the Caracol at Chichén Itzá.

The plan of the Caracol, showing alignments to: A, summer Solstice sunset; B, summer Solstice sunrise; and C, winter Solstice sunset.

Much of the mystery surrounding the ancient Maya is currently being dispelled by the study of their surviving Central American descendants, who have preserved much of their cultural heritage. Among the modern Maya, the priestly or shamanic function is performed by individuals known as “daykeepers” or “sunkeepers.” One of the duties of the daykeeper is to regulate the calendar by observing the Solstices and Equinoxes. Near the town of Nebaj, Guatemala, American anthropologist J. Steward Lincoln found that such observations were still being facilitated (as of 1940) by the use of towers, standing stones, and stone circles similar to ones that date back to the earliest Pre-Classic period of Mayan culture.

The Aztecs of southern Mexico presided over the last, brief flourishing of native civilization in Central America. They built what was unquestionably among the most violent societies that has ever existed: their cities fed on incessant human sacrifice (which was, incidentally, not unknown to the Mayas), and their pantheon consisted almost entirely of demons. And yet Aztec songs and poetry dwell endlessly on images of magical birds and flowers. Ptolemy Tompkins suggests in his brilliant and disturbing book This Tree Grows out of Hell: Mesoamerica and the Search for the Magical Body that the Mayan/Aztec obsession with death may have been the end result of a gradual corruption of the tribal shaman’s ecstatic flight from the body, and of the universal longing to return to an original, ideal paradise by shedding the mortal coil. With civilization, it seems, comes alienation not only from the Earth but also from the wellsprings of renewal within the human body and psyche; human sacrifice served as these people’s desperate attempt to reach the steadily-receding Otherworld:

Whereas the Maya appear to have practiced human sacrifice primarily as a method of personal, individual aggrandizement, sacrifice among the Aztecs was a far greater entity.…Sacrifice was a primary cosmic principle in this universe—an a priori factor as important as time and space, and hence an essential tool for human beings desiring to enter into contact with the supernatural forces that gave shape to the world.8

At the time of Montezuma—the last ruler of the intact Aztec empire, who died at the hands of Cortez—sacrificial victims routinely waited in lines up to a mile long to have their hearts ritually torn from their chests and held up to the four directions. Even battle-hardened Spanish soldiers were revolted by the stench of death that clung to the bloodstained stairways of the Aztec pyramids.

If indeed the Aztecs’ methodical rites of human sacrifice were the decadent expression of a longing for the experience of shamanic ecstasy, they occurred in a context that preserved other elements of the shamanic worldview in corrupted form as well. As we have seen, many ancient peoples kept track of the Solstices by means of simple sighting sticks or standing stones. The Aztecs likewise celebrated the Sun’s seasonal motions, but used a far more elaborate means to do so.

The ceremonial focus of Tenochtitlan, the Aztec capital, was the Templo Mayor, a pyramid surmounted by two symmetrical tempies. Immediately to the west, across a plaza, stood a smaller, cylindrical Temple of Quetzalcoatl. According to archaeoastronomer Anthony Aveni, who surveyed the site, the Templo Mayor was “a functioning astronomical observatory” whose main purpose was to announce the Equinoxes. One morning each spring and autumn, observers standing on the steps of the Temple of Quetzalcoatl would see the Sun rise in the notch between the two temples atop the eastern pyramid.

The fact that the Aztecs aligned their principal religious structure with the equinoctial sunrise is partly to be explained by the fact that they celebrated the main festival of the god Xipe Totec at the vernal Equinox. But it may have another, darker significance as well. An illustration of the legend of the founding of Tenochtitlan in 1325 in the Aztec Codex Mendoza shows an eagle using its talons to rip the fruit from a cactus. The eagle symbolized the Sun, and the cactus fruit was the equivalent of a human heart. In the minds of the Aztecs, the main purpose for their painstakingly choreographed rituals of human sacrifice was to keep the Sun alive. Perhaps they perceived the Equinoxes as signs of reassurance that their efforts were effectual.

The Andean Incas began their ascent to empire about three hundred years before the voyage of Columbus, building on foundations laid by a long series of native Peruvian cultures. When Francisco Pizarro arrived in the early sixteenth century, he found a highly organized socialist society stretching fifteen hundred miles from Equador to Chile, with a population of perhaps six million. The Incan economic system lacked markets, merchants, or money, yet managed to provide a sufficiency of food and other basic necessities for all. Other achievements included monumental stone fortresses, suspension bridges, an extraordinary legacy of cultivated medicinal and food plants (including many varieties of potato and maize), and a system of paved roads and runners by which messages could be sent a distance of 150 miles in a day.

The Incan high god was the nameless Source of all life, whom they addressed by the title Wiraqoca (or Viracocha). Popular religious rites were devoted to lesser deities, such as Pachamama, the Earth mother; Inti, the Sun; as well as the gods and goddesses of the Moon, sea, and thunder; and to the huacas, a collection of over three hundred sacred sites that included springs, fountains, caves, hills, tombs, and houses. At the center of the Incas’ capital, Cuzco, stood the Coricancha (or Sun Temple), oriented toward the winter Solstice sunrise, in whose innermost shrine were hung magnificent solid gold Sun discs.

According to the Inca creation myth, the first Incas (the young emperor and his sister-bride) were sent to Earth from their father, the Sun, to find the place where a golden rod he had given them could be plunged into the soil. This mythic rod probably represents the Sun’s perfectly vertical rays at noon on zenith day.

Around 1600, Garcilaso de la Vega, the son of a Spanish captain and nephew of the eleventh Inca ruler, compiled his Royal Commentaries of the Incas, in which he described a sacred group of gnomons, or Sun-sticks, near Quito, which lies close to the equator. There, the Equinox Sun passes through the zenith at noon, affording the Inti, in Garcilaso’s words, “the seat he liked best, since there he sat straight up and elsewhere on one side.” North or south of the equator, the zenith days and the Equinoxes are not synchronized; but Incas at all latitudes throughout the tropics watched their gnomons until “at midday the sun bathed all sides of the column and cast no shadows at all.…Then they decked the columns with all the flowers and aromatic herbs they could find and placed the throne of the sun on it, saying that on that day the sun was seated on the column in all his full light.”9

From the Sun Temple in Cuzco, forty-one imaginary lines or ceque radiated out, each marked along its length by huacas. Anthony Aveni has demonstrated that one of the more prominent ceque served as a sighting line to a hilltop huaca, which was the foresight for the viewing of the December (summer) Solstice sunset from the Coricancha temple. The functions of other ceque, as well as those of the famous and mysterious lines on the Nazca plain, remain unknown.

Two of the Incas’ most important festivals were held on the Solstices. Inti Raymi was the winter Solstice festival, held in June; the summer ceremony, Capac Raymi, was held in December. Astronomer E. C. Krupp describes the Inti Raymi rite as follows:

Before dawn on the day of the winter Solstice the Sapa Inca [the emperor] and the curacas in the royal lineage went to the Haucaypata, a ceremonial plaza in central Cuzco. There, they took off their shoes as a sign of deference to the sun, faced the northeast, and waited for the sunrise. As soon as the sun appeared, everyone crouched, much as we would get down on our knees, and blew respectful kisses to the glowing gold disk. The Sapa Inca then lifted two golden cups of chicha, the sacred beer of fermented corn, and offered the one in his left hand to the sun. It was then poured into a basin and disappeared into channels that conducted it away as though the sun had consumed it. After sipping the blessed chicha in the other cup, the Sapa Inca shared it with the others present with him and then walked to the Coricancha.…10

For the Sapa Inca, the day’s ceremonies continued in the Coricancha’s Sun Room, which was lined with gold plates. A fire was lit by focusing the Sun’s rays with a concave mirror, and sacrifices followed.

During the past few decades, the Kogi Indians have watched as the climate has changed in the Andes mountains of Colombia as the result of pollution and deforestation. They regard the civilized white race as the “younger brother,” and have issued a warning that unless the younger brother desists in ravaging the natural environment, the Earth herself will sicken and die. In 1990, the Kogi were the subject of a ninety-minute BBC television documentary produced by Alan Eleira, titled “From the Heart of the World: the Elder Brother’s Warning.” Eleira has more recently produced a book on the Kogi, Elder Brothers.

The Kogi visualize the cosmos as a great spindle with nine levels, and oriented in six directions (up, down, northwest, southeast, southwest, and northwest). The latter four directions refer to the sunrise and sunset extremes at the Solstices. Kogi temples are patterned after the spindle-shaped universe. The Kogi mama, or shaman, lays out the groundplan of the temple with a cord and stake. He locates the four corners of the structure by lining the cord up with the summer and winter Solstice sunrise and sunset points on the horizon. At noon on the June Solstice, the Sun shines through a hole in the very top of the temple—which the mama uncovers for the occasion—and from dawn to sunset moves between carefully positioned fireplaces. The Kogi liken the movement of the Sun to the act of weaving. E. C. Krupp writes: “Through the year, as the sun moves north, south, and north again, it is said to spiral about the world spindle. It weaves the thread of life into an orderly fabric of existence, and the cyclical changes of the sun’s daily path are transformed into a cloth of light on the temple floor.”11 The Kogi believe that it is the duty of human beings to assist in the weaving process, and to order their own lives according to the warp and weft of the universal pattern.

In the Amazon, the Equinoxes coincide with the start of the two rainy seasons—one in March, the other in September. The Desana and Barasana Indians see connections between everything that happens on Earth—and particularly, the availability of fish and game animals—with what they see in the sky. They see the night sky as a great brain, with its two hemispheres divided by the Milky Way. According to the Desana-Barasana creation myths, on the First Day the Sun Father fertilized the world at its center by there erecting a perfectly vertical rod. It was from this spot that the first people emerged. The place where the Desana-Barasana believe this primordial event occurred happens to lie almost exactly on the equator. Thus, each spring and fall Equinox, when the Sun is directly overhead, and an upright staff casts no shadow, the Desana and Barasana believe the Sun’s rays are again directly penetrating the Earth, making the world fertile and new.