CHAPTER 6

Festivals of Heaven and Earth in the Far East, India, and Polynesia

CHINA IS NEARLY UNIQUE among the world’s cultures in that its mythology contains no memory of ancient folk migrations. The Chinese believed that they originated where they are today, and they called their land the Middle Kingdom–the center of the world. Moreover the earliest Chinese mythology, rather than describing the creation of the Universe and the origin of evil, tells instead of the first Emperors, who are said to have developed agriculture, the domestication of animals, and writing. This legendary history extends back to about 3000 B.C.E. While most Western historians regard the legendary first Emperors as purely fictional, the Chinese people continue to believe in them and are somewhat justified in doing so by the fact that theirs is unquestionably one of the oldest continuous civilizations on Earth.

Yao, the fourth of these legendary Emperors, is said to have devised a calendar for the purpose of regulating agricultural activity throughout the land. The Book of Records describes instructions which “the Perfect Emperor Yao [in 2254 B.C.E. gave] to his astronomers to ascertain the solstices and equinoxes…and four seasons.…”

From its beginning, Chinese astronomy served an oracular function. Priests of the Shang dynasty (1500-1100 B.C.E.) recorded celestial observations on engraved bones, which they then exposed to fire so as to “read” the answers to their questions in cracks formed by the heat. Later, when the country was unified under the Emperors, astronomy became the province of a government department, and consisted of carefully recording celestial phenomena (particularly the unusual ones, such as eclipses and comets) and then interpreting their astrological significance not only for the state, but for nearly every aspect of the daily life of the people.

To the modern scientific astronomer, the traditional Chinese stargazers present a paradox. On one hand, their accuracy and persistence resulted in the production of the most complete and reliable record in existence of eclipses, comets, and supernovae for the past two millennia. On the other hand, however, their preoccupation with bureaucracy and mythology kept the Chinese from making even the most rudimentary inquiries into the mechanics of solar, lunar, and planetary motions.

At the time of the Shang dynasty, according to indications on a few of the thousands of oracle bones that have been recovered and studied, the year was divided into quarters (bounded by the Equinoxes and Solstices) by measuring the length of the shadow cast by a gnomon, or Sun-stick. The Shou dynasty, which followed the Shang in 1100 B.C.E., left behind hundreds of pyramids in the Wei River valley of the Shensi province, many of which appear to incorporate celestial alignments. A significant number are oriented to the Equinox sunrise. Unfortunately, however, we know little about the exact nature of the seasonal rites of the preimperial era because virtually all books and records were destroyed in 213 B.C.E. by the edict of the first Emperor, Qin Shihuangdi. At around that time, however, the imperial court instituted calendrical rites that continued with little alteration until the early twentieth century. The beginning of the year was situated halfway between the winter Solstice and the vernal Equinox, in the middle of February. But significant festivals were held on the summer and winter Solstices, when the Emperor symbolically renewed the world order.

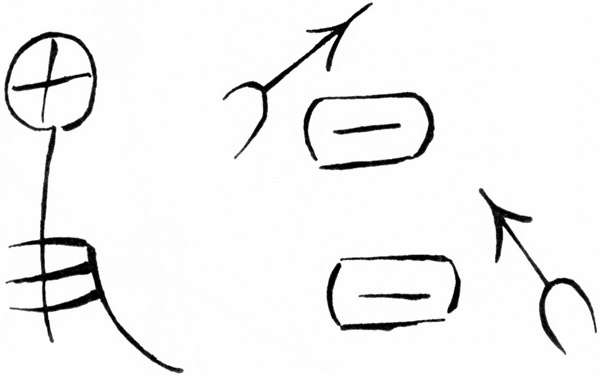

Shang characters carved in oracle bones. The character at left may represent a gnomon used to determine the solstices. The ones at right may portray the sun, with shadows of human figures shown at differing angles to indicate different times of the year.

Three days before the Midwinter ceremony, the Emperor began a process of purification, abstaining from women, music, certain foods, and other activities. Then, two hours before sunrise on the morning of the Solstice, a procession of royalty, officials, musicians, singers, and dancers brought him to the Round Mound in Beijing’s Temple of Heaven just south of the Forbidden City.

Norman Lockyer quotes an account of the ceremony that followed, written by an explorer named Edkins in the nineteenth century, when these yearly Solstice ceremonies were still being performed:

The Emperor, with his immediate suite, kneels in front of the tablet of Shang-Ti and faces north. The platform is laid with marble stones, forming nine concentric circles; the inner circle consists of nine stones, cut so as to fit with close edges round the central stone, which is a perfect circle. Here the Emperor kneels, and is surrounded first by the circles of the terraces and their enclosing walls, and then by the circle of the horizon. He thus seems to himself and his court to be in the centre of the universe, and turning to the north, assuming the attitude of a subject, he acknowledges in prayer and by his position that he is inferior to heaven, and to heaven alone. Round him on the pavement are the nine circles of as many heavens, consisting of nine stones, then eighteen, then twenty-seven, and so on in successive multiples of nine till the square of nine, the favourite number of Chinese philosophy, is reached in the outermost circle of eighty-one stones.

The observatory of Guan Xing Tai at Gao Cheng Zhen, constructed in 1279 C.E. The differences in the lengths of the shadows cast at the summer and winter Solstices by the horizontal rod at the opening of the forty-foot tower enabled precise measurement of the tropical year. (After Krupp)

The same symbolism is carried throughout the balustrades, the steps, and the two lower terraces of the altar. Four flights of steps of nine each lead down to the middle terrace, where are placed the tablets to the spirits of the sun, moon, and stars and the year god, Tai-sui.1

After lighting a fire, the Emperor read an account of the last year and made ceremonial sacrifices to heaven, consisting of incense, jade, and silk. Finally, a portion of roasted human flesh from a sacrificial victim was offered up. After bowing nine times to the north, the Emperor descended the Round Mound.

The view south along the shadow measuring wall to the tower. The horizontal bar (reconstructed) casts a shadow on the wall, permitting the exact calculation of the Solstices. (After Krupp)

The summer Solstice ceremony was a complement to the December rite. While the winter festival was held to honor and energize the celestial, male, yang forces in order to counterbalance the natural predominance of yin that occurs in that season, the summer celebration was earthy, feminine, and yin in character so as to stimulate those forces when they are naturally at their weakest. The summer rite took place on the Altar of the Earth, Di tan, just north of the Forbidden City, which was square so as to evoke the terrestrial forces, just as the Round Mound was circular and heavenly; both structures had a stairway leading in each cardinal direction. While the winter Solstice’s sacrificial victim was burned so that the smoke could rise to heaven, in summer the sacrifice was buried.

By participating on behalf of humanity in the Earth’s natural rhythms, the Emperor aided both the land itself and human society to maintain a healthy balance. His influence was believed to extend even into the cosmos for, in the Chinese system, all things in Heaven and Earth were interconnected and interdependent.

Japan’s religious and mythic tradition, called Shinto (from the Chinese shen-tao, meaning “the way of the higher spirits”), preserves the story of two original ancestors, Izanagi and Izanami, who came down to Earth from Heaven and created the eight islands of Japan and then various deities, including the Sun-goddess Amaterasu. All Japanese Emperors are believed to be direct descendants of Amaterasu and, because of this, Japan is thought to have a unique and divine mission on Earth. All of the Japanese people have a sacred kinship with the Emperor, and the details of their kinship relations with him and thence with various deities comprise a complex ancestor cult.

Japan’s astronomy—like so much of her culture—was strongly influenced by China. In the early part of the seventh century a priest named Mim was sent to China to study Buddhism and astronomy. When he returned, he opened Japan’s first astronomical observatory at Asuka and founded the Imperial Department of Astronomy, which was charged with the interpretation of unusual celestial events. The Asuka royal astrologers discovered Halley’s Comet in October of 684, nearly a millennium before Edmund Halley was born. But the observatory fell into disuse only a few centuries later, and today all that remains are two carved megaliths One of these stones, weighing 950 tons, is regarded by tradition as having miraculous powers; the second has a series of grooves along its upper surface that point toward the Solstice and Equinox sunset points.

The Japanese New Year was formerly celebrated on Toji, the winter Solstice, but now on January 1. Particularly in prewar times, the night before the New Year was marked by the appearance of funerary animals (horses, etc.), and of the gods and goddesses of the spirit world. Secret societies paraded in masks, and troupes of dancers went from house to house rattling bamboo sticks in order to clear out malevolent spirits. Also at this time, the dead were believed to visit the living. It was on the Solstice that Kami reentered the world and gave it new life for the coming year.

Today, the New Year is the most important festival in the Japanese calendar. Arrangements begin many days ahead, with the preparation of special foods and the decoration of houses. Schools close around the time of the December Solstice, and much time is given over to parties. No one works for the first three days of the year, and, in the more traditional families, members exchange gifts and visit shrines.

The Japanese also celebrate the vernal and autumnal Equinoxes. Spring Equinox Day (Higan) is a national holiday and the start of a Buddhist festival that celebrates nature and all living things. On Autumn Equinox Day, people customarily visit family graveyards and offer flowers and food to their ancestors.

According to the Surya Siddhanta, a Hindu astronomical text, the celestial traditions of India date back to the year 2,163,102 B.C.E. While few modern archaeologists or historians accept this figure as having anything other than mythological significance, it is true nevertheless that Indian astronomy comprises an ancient and complex tradition.

Hindu astronomers were in the habit of discussing enormous time periods—cosmic cycles called yugas and kalpas—lasting hundreds of thousands, millions, and even billions of years. According to their reckoning, we are now living in the Kali Yuga, which (according to some calculations, at least) began on Friday, February 18th, 3102 B.C.E., and will last another 428,000 years. The Dwapara Yuga, which preceded it, was of twice that duration; and the Treta Yuga, still earlier, lasted three times as long. The first world age of the present series, the Krita Yuga, which was a paradisal Age of Gold in which humans were twenty-one cubits tall and lived four hundred years, was four times the duration of the present Kali Yuga. But a kalpa, according to Brahmagupta, writing in the year 62c, lasts a full 4,320,000,000 years—a figure approximating geologists’ estimates of the age of the Earth. If we take both the mythic and scientific figures seriously, and if we are indeed nearing the end of a kalpa, this could present cause for alarm since, according to tradition, at the end of each kalpa the world is destroyed by fire and recreated.

Like their Babylonian and Chinese counterparts, the Brahmin stargazers of ancient India used their celestial observations primarily for astrological purposes. Their cosmology consisted of a flat Earth with a sacred mountain at the center around which the Sun, Moon, and planets orbited—though this picture gradually changed as a result of the introduction of Graeco-Roman astronomical concepts via Alexandria. The Brahmin astronomers noted that the Equinoxes occur at slightly different points of the zodiac each year, but it would be incorrect to say that they discovered the phenomenon of precession since they explained the discrepancy by proposing that the Equinox swings to and fro with a period of seventy-two hundred years.

For the early Indie peoples, as for all ancient cultures, the sky had a profound religious significance. The earliest religious texts of India, the Vedas, which constitute the oldest living religious literature in the world, identify nearly all the major deities with celestial objects. Surya, Vishnu, and Varuna, for example, were all associated with the Sun.

Perhaps the earliest elements of Vedic religious practice consisted of the kindling of sacred fires and the performance of a varied and complex schedule of sacrifices. The purpose of these sacrifices was the reenactment of the creation and the sustenance of the cosmic order. According to P. C. Sengupta, an authority on early Indian astronomy, “The chief requirements for the performance of Vedic sacrifices were to find as accurately as possible the equinoctia and solstitial dates, and thence to find the seasons.”2

The Hindu calendar has always been based on the cycles of the Moon. Nevertheless, the peoples of many parts of India marked the Solstices and Equinoxes with festivals. For example, northern Indians greeted the winter Solstice with the ceremonial clanging of bells and gongs in order to frighten away hurtful spirits—a custom widespread among all Indo-European peoples.

In the next chapter, we explore Solstice rites that developed among the Indo-Europeans who migrated west and north into Europe. But elements of the same tradition also traveled east and south.

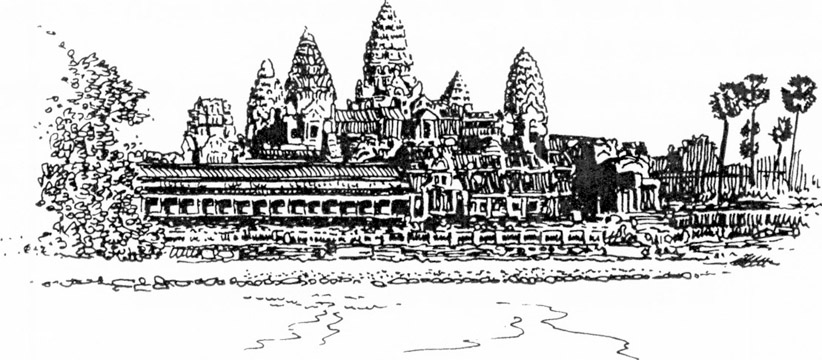

Over the course of the last three millennia, the Southeast Asian festival calendar has been influenced by customs imported from Babylonia, China, Muslim Arabia, and India. One example of Hindu influence is the vast temple complex of Angkor Wat in northeast Cambodia, built during the reign of Suryavarman II (C.E. 1113–1150) as a tribute to the god Vishnu. It comprises over two million square meters of temples, walls, galleries, and courtyards, all of which attest to the vision of an architectural genius.

In an article in Science in 1976, astronomers Robert Stencel, Fred Gifford, and Eleanor Moro’n reported on the results of their study of maps and charts of Angkor Wat (they were prevented from conducting on-site surveys by the ongoing Cambodian civil war). They concluded that the temple has “calendrical, historical, and mythological data coded into its measurements” and incorporates “built-in positions for lunar and solar observations.” They noted also that “the sun was itself so important to the builders of the temple that even the content and position of its extensive bas reliefs are regulated by solar movement.” The axis of the complex is oriented in such a way that an observer standing at the western entrance gate can see the Sun rise at the spring Equinox immediately over the central tower of the complex. From the same observing position at the western gate the summer Solstice sunrise occurs directly over the most prominent hill on the horizon, and the winter Solstice sunrise takes place over a small outlying temple 5.5 kilometers southeast of Angkor Wat.

In the traditional Cambodian calendar, the New Year—Chaul Chham—commenced around the time of the spring Equinox and was celebrated by a three-day suspension of normal activities. During the first seven days of the year no living thing could be killed, no business transacted, and no litigation conducted. But the Khmer (ethnic Cambodian) calendar is lunar, and so the timing of the festival in the solar year has shifted somewhat. It is now celebrated in mid-April.

Angkor Wat.

The wide-ranging Polynesian peoples of the Pacific—inhabiting New Zealand, Hawaii, Tahiti, Samoa, Easter Island, and the Tonga, Cook, and Marquesa Islands, among others—began their migrations from Southeast Asia to Tonga over three thousand years ago. Eastern Polynesia was settled much later, with the first people arriving in the Marquesas, Tahiti, Hawaii, and Easter Island by the year 700, and New Zealand by 1100.

The Polynesians were horticulturalists, cultivating taro, yams, breadfruit, and coconut. They were also, by necessity, keen navigators, whose skills are only now beginning to be understood by scientists. At the time of their first contact with Europeans, they were engaged in planning voyages of up to five hundred miles in length. They found their way from island to island by a thorough understanding of tides, winds, wave patterns, and bird behavior, as well as a detailed knowledge of the stars. Each island was said to be ruled by particular stars—which meant that from that place, those stars would be seen to pass directly overhead. This was an effective means of determining latitude; once the navigator had steered his vessel to the point at which the proper star passed overhead, all that was left was to set course due east or west toward his destination. The Polynesians visualized the night sky as the ceiling of a great house with rafters and cross beams, with prominent stars at key intersections. Using this mnemonic device, they were able to recall the relative positions of hundreds of stars.

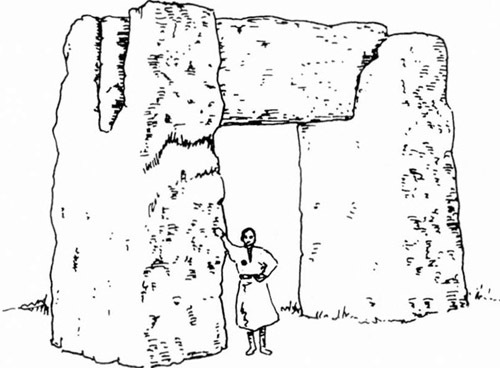

The stone trilithon at Tonga Tabu, called the Ha’amonga’a (After Childdress)

The Polynesians’ astronomical interests were not confined to the night sky, nor to the needs of navigation. They noted the seasonal movements of the Sun as well, a practice possibly predating their departure from Asia.

In Tonga, the site of the earliest Polynesian settlements in the Pacific, a huge rough-hewn coral megalithic arch fifteen feet high and eighteen feet long called the Ha’amonga’a Maui is aligned to the summer Solstice sunrise. Moreover, a series of grooves on the upper surface of the largest of the stones points to the winter Solstice sunrise. On the winter Solstice (June 21), 1967, king Taufa’ahua Tupou IV observed the sunrise from this spot, confirming the accurate alignment of the marks on the lintel. According to legend, the trilithon was erected by the god Maui with stones from the sea. This, however, is tantamount to a profession of ignorance on the part of the natives, since they are in the habit of attributing to Maui all otherwise unexplainable phenomena.

The Maori of New Zealand personified Heaven and Earth as the sky-god Rangi nui and the Earth-goddess Papa tu a nuku. It is said that during the year, the Sun roams from Rangi’s head to his toes and back again. When the Sun is near Rangi’s head, it is summer; when at his feet, it is winter. They also say that when the Sun is near Rangi’s head he is spending time with Hineraumati, the Summer Maid. He departs from her in December, however, at the time of the summer Solstice, and heads far out to sea, where lives Hine-takurua, the Winter Maid. There the Sun stays until the June winter Solstice, when he heads back toward land.

In Hawaiian mythology, the spirit of the Earth is again called Papa, but the sky is personified as the god Wakea (whose name, literally, means midday). The two great cosmic principles are also referred to as Ku and Hina—names and terms that convey much the same meaning as the Chinese Yang and Yin. Ku and Hina may refer to husband and wife, Heaven and Earth, sunrise and sunset, or generations gone and those yet to come.

The land furthest to the east—that is, toward Ku—in all the Hawaiian Islands is Makapuu Point on Hawaii. There the mythical figure Kolea-moku (muku) is represented by a red stone at the extreme end of the point. “Two of his wives,” according to Martha Beckwith, the great collector of Hawaiian lore,

also in the form of stones, manipulate the seasons by pushing the sun back and forth between them at the two Solstices. The place is called “Ladder of the sun” and “Source of the sun” and here at the extreme eastern point of land of the whole group, where the sun rises up out of the sea, sun worshipers bring their sick to be healed.3

This Hawaiian myth may be the remnant of an elaborate, ancient tradition of astronomical observations and seasonal festivals; it is impossible to tell. At any rate, the three stones suggest a system of foresights and backsights, such as were commonly used in megalithic Europe and the Americas to determine the times of the Solstices and Equinoxes for the purpose of great communal celebrations.