“When you were out there you were pretty much on your own unless it was something very serious. I don’t remember too many people ever being sent to St. John’s other than terminally ill patients.” Avery (45)

In rural Newfoundland nursing was delivered in nursing stations, cottage hospitals and by public health nurses throughout the province. Rural nursing was composed of any nursing taking place outside larger hospital settings with little or no access to services such as laboratories, x-rays and operating rooms. Nursing stations were small ‘hospitals’ in coastal communities which were manned solely by nurses, in many cases only one nurse. Cottage hospitals were very somewhat larger than the nursing station with a doctor on staff along with one or two nurses. Public health nurses often had no building to house their practice but worked out of their homes and were frequently on their own in their districts. Working conditions for all these nurses differed according to their proximity to St. John’s.

Nursing in rural Newfoundland in the 1930s and 40s was an isolating experience. The nurse decided whether she could treat a health problem alone or if additional services were needed. This could mean something as simple as consulting a doctor in a larger center, or it could mean transporting the patient to another community at a time when provincial transportation was not easy. Ultimately, the nurse had to feel confident her decision was the best possible solution and had to be accountable for any decisions made. In many respects she functioned similarly to the nurse practitioner of today.

Nursing Stations: The most isolated form of rural nursing was the nursing station. In northern Newfoundland and Labrador, nurses worked for the International Grenfell Association which opened its first nursing station in 1908 in Forteau, Labrador. Most of the nurses who went to nursing stations in Labrador and northern Newfoundland at that time were from out of the country, often British nurses, young women out to have an adventure. Some stayed longer but most stayed for the two years required by their contract and then returned to England. It was unusual for Newfoundland trained nurses to work in these areas. Penney and Ashbourne indicated that in the late 1940s and early 1950s, the nurses working at St. Anthony were mostly American, likely recruited by NONIA.

The focal point for the Grenfell Association and health care in northern Newfoundland was the Grenfell Hospital in St. Anthony. This hospital received emergency patients and served as a source of advice and information to nurses in remote nursing stations. Doctors from there would travel out into the communities for clinics and visit patients referred by the nurse. Nurses, who were based in coastal communities, lived in and worked out of the nursing stations. These nursing stations served as their home and as a hospital for patients. In these stations the nurse was the only person with any education in health and she worked with very limited resources.

Taylor came to southern Labrador as a missionary which was unusual. She was located in Forteau on the southern Labrador coast and was responsible for communities from there to Red Bay about 40 miles north. “They tried to persuade everybody (patients) to come up to the nursing station. There were some local midwives who were local women but not real midwives. The people would stay in different homes if they had friends here and then some of them would stay at the nursing station. We tried to get them to stay there. This was just during the days when travels were by boat and dog team. When the road came through we didn’t always have the same problem. That was about ’56. Twice a year the doctor from St. Anthony came. They came in the little mission boats in the fall and in the summer and during the winter everybody came by airplane.” When the road was put through to Red Bay the people had better access to health care facilities.

Nurses in the stations also traveled to isolated communities to bring health care to the people. Taylor recalls such a visit to Red Bay, “About 50 miles… I went down on one of the coastal boats. I came back by motor boat. I was going to do a clinic. Clinics in all the different communities were in somebody’s house. [The previous nurse] told me which houses we went to. They probably volunteered. It was done before I got here. [I saw] children, antenatals, anything; the same as you would in a clinic. Earaches and sore throats and chest infections and measles. We had medications. It was given to treat our own patients. I had to diagnose and treat. In antenatal, you made sure they were healthy. Immunizations sure. And we’d do home visits when we went out. Then I went to the next community which was where people went during the summer for fishing. It’s behind Red Bay, a couple of minutes by boat.”

Because these nurses were the only people in the community who were knowledgeable about health care they were never off duty. Taylor, “I remember going up to Lanse au Loop for a concert and in the middle… somebody came up to me and said, ‘Nurse what’s this thing on my wrist?’ It was a lump or something. And I remember the nurse’s aide who was there when I first came, she went to get married and at the wedding, somebody decided to fall into the brook and nearly get drowned. So I got called out, of course.”

Labrador and northern Newfoundland presented many challenges to the nurses working in these isolated areas. Penney, who worked with Community Health in St. John’s, volunteered to go to St. Anthony and transport a patient who needed to be admitted to the hospital in St. John’s. She traveled there in a small plane and became stranded when the plane had mechanical difficulties; “In St. Anthony once navigation closed in the fall, they didn’t see anybody again ’til the spring, so it was great to have the plane come in. We landed on the ice and everybody in the whole community was down because I could see them coming. You know, it was great! And then actually he couldn’t get the plane off for a couple of days. We were there for almost two weeks before we got out of it.”

During her time in St. Anthony, Penney had an opportunity to meet one of the English nurses in a nursing station; “She was an English nurse. There were English and American [nurses] mostly there. But they were wonderful girls because they worked hard and under all sorts of poor conditions. Well because I was down there for two weeks, they said to me, ‘Would you like to come across to Hooping Harbour? We’re going across by komatik [dogsled].’ They had their nursing station over there. And they had to bring some supplies over there for her. She had a direct line with a doctor there and she would call. I thought that girl was really great. She had amputated two toes, but it wasn’t hard to amputate them because gangrene had set in and they were falling off anyway. She was really busy there [in] Hooping Harbour. She was assigned there from Grenfell [Hospital].”

Cottage Hospitals: In 1936, the Department of Health opened cottage hospitals in an effort to organize delivery and improve the standards of health care throughout the province particularly in rural areas. These were generally small but were different from nursing stations in that cottage hospitals had a doctor on staff along with nurses. The doctor was definitely in charge but the nurse was responsible for the day to day operations of the hospital and also did most of the patient care. Nurses in cottage hospitals were the live-in staff and like nurses in nursing stations were on-call more often than not.

Roche was employed as a supervisor in the cottage hospital system. “We had to work eighteen cottage hospitals at a time and we had it divided up into three each [per supervisor]. I did the South Coast, someone else, the Northeast, and somebody else did the West Coast. We had to check out everything in these hospitals; we had to check problems that nurses were having with doctors and sort them out. Some of the hospitals only had a few nurses and they worked very hard. There were usually only two doctors there.” She explained the nursing structure in the Department of Health at the time, “There was the director, an associate director, and eventually, we became assistant directors.” Although the nursing supervisor did not have a great deal of influence in the working of the department they were responsible for most of the staffing in the hospitals. Roche, “We had very little to do with the secretary’s employment or the people that worked with them. We employed the nurses and when we could, we interviewed. The nursing assistants were usually employed directly by the nurse in charge of the hospital.” The supervisors were also responsible for the midwives in the area. Roche, “I only ever got to see two or three of them. Because they were all in little coves that the boats could not get into.”

Griffen describes what it was like to work in Botwood Cottage Hospital; “But then, you worked every morning… well, you went to work at 8:00 a.m but you lived in the hospital. There were only two nurses. Every second night, you were on call. So, that night, you couldn’t go to bed until 1:00 a.m. or 2:00 a.m. depending on what was going on. And all the medications were given out because we had nurse’s aides in those days but, they only gave bedpans and did stuff like that. And if anything came in the night like anybody in labour or an accident or anything, you had to get up. But you still had to go to work the next day whether you got in bed or not. [This happened], quite often. Every day and every second night was your call. While the nurses were in surgery the nursing assistants would look after the patients.” The interdependence of the groups was obvious.

Avery who worked in Old Perlican relates a similar story; “We had one cook for the hospital, our water was brought by gravity from a pond above the hospital, and we hired ladies from Old Perlican to come in on Mondays. We did not have a washing machine so they had to do the laundry by scrubbing the clothes on boards. That is the way it was. We actually lived in the Cottage Hospital upstairs. The other nurse and myself each had a room and we shared a common bathroom with the three nursing assistants. One of the assistants would do the night duty, and when women would go into labour, [she] would come and call us. I’ve delivered babies in my dressing gown. The doctor was close by, only being across the road, but he was not always available. There was a nurse in charge and when that nurse was gone, the second nurse was in charge and they did whatever had to be done.”

Hutchings worked in Rocky Harbour Cottage Hospital in preparation for being the lone community nurse in Cow Head. “We really didn’t have any time off. One of us was on call every night. And maybe we’d have Saturday afternoon off or Sunday but we never spent the night [away from the hospital]… maybe go for a walk or you’d go out to the store. I used to do a fair amount of walking.” Life for a nurse in a cottage hospital was demanding with little free time. The community depended on the nurses to be available whenever needed and didn’t imagine that they would need personal time. Avery, “They’d get in such a state and they think there is nobody there to do it. It had been near Christmas and I was gone into Old Perlican to buy some decorations for the hospital. When I got back, they were there at the door and I thought for sure I was going to be fired!” The nursing assistants and patients felt deserted because she wasn’t immediately available.

Much of the work done in cottage hospitals depended on the skills and interests of the medical staff, the staffing available, the degree of isolation of the hospital and the resources available. Like their colleagues in the bigger centers, the nurses in cottage hospitals also performed multiple roles when caring for patients. In Rocky Harbour there was no way to transport patients and the staff had to take care of all patient care. Hutchings, “We had two rooms for obstetrics. We had an Operating Room. And downstairs we had a really cramped outpatients and in the outpatients was Dr. Murphy’s office. And outside of his office we had a great big long counter with all the medications on it and that’s where the nurse worked. He would see the patients and then he’d send them out to you with a little slip of paper and whatever medications they had to have. We had to fill the medications and sing out to them {the patients] and they’d come and get it. He would try to do the ones with x-rays before 11:00 o’clock and then he’d always have a break for a cup of tea or go upstairs in the sitting room, the nurse’s sitting room upstairs, and we’d have a cup of tea and maybe a sandwich. And then he’d come down and do his x-rays himself and read them and come back and call the patients in again. And he did a lot of deliveries.” Botwood was isolated, but there was some communication with the hospital in Grand Falls. As Griffen stated, “Dr. Rowe did big surgery. And even Dr. Strong, from Grand Falls, used to come down and they’d do hysterectomies and bones and anything that occurred. Dr. Rowe would do it, Noonan gave the anesthesia and I elected to assist.”

Avery worked in Old Perlican, nearer St. John’s and its larger medical centers. “Normally, there were eleven patients. You could probably have 12 or 13 because you could put in two more beds. They did a lot of operations at Old Perlican Cottage Hospital. We pulled teeth and did everything. We sterilized our instruments and made up trays. I was a scrub nurse all the while I was there, I put in every effort for every operation that was there.”

The cottage hospital system required that families pay a yearly fee for medical care given in hospital but drugs, maternity and dental care cost extra. Hutchings, “Now in the cottage hospital system, they saw the doctor for free and it didn’t cost them anything to have x-rays or anything like that, but the medications, in a lot of cases, they paid for unless they were on welfare and then we’d pay for it and mark it in.” The decision to access health care could hinge on the ability to pay. Avery shared a story of how the inability to pay impacted on the lives of the people. “This lady went into labour in Old Perlican. I requested that she be brought in and he [her husband] said ‘No. It would cost too much money.’ So he called me out. When I got out there she was in heavy labour and she was bleeding a lot. I brought her in and got her into the case room and cleaned her up so I could see what we were doing. I saw that it was placenta previa. I had her there a little while and I was trying to get the doctor. It was after 10:00 o’clock by the time that I got her in. The phones were cut off at 10:00 o’clock and I could not get any phone-calls until 8:00 o’clock in the morning. When I got her in I gave her a shot of Morphine and prayed that it would hold her until morning, but it didn’t, of course. She woke up about 1:00 or 2:00 o’clock and delivered immediately and it was a dead infant. Everything was separated and the sac wasn’t even broken. I was so hopeful that maybe the baby was alive. It was such a beautiful baby. The next morning I got a hold of the doctor and we got her fixed away in the bed. At this time she was aware that the baby was stillborn. I believe that the baby was dead when I got out there the night before, because I could see something but I did not know what it was. Anyway, I told the doctor what I had done and that I had sat with her. He fixed everything off and that was it.” This story provides insight into both the difficult conditions under which nurses worked and the impact of not having ready access to health care but it also shows the measures nurses were prepared to take in order to care for their patients.

Griffen was also expected to do visits by boat. “We were in Botwood one night, they sent a boat [because there was] a woman in labour somewhere and I went with Dr. Rowe. We steamed for an hour and a half wherever we went and you’d blow when you get into a harbour, the captain blows to get somebody to come out. So this man arrived out in the little boat and he said to Dr. Rowe, ‘Doctor’ he said, ‘the man above got here before you.’ So Dr. Rowe said, ‘Well done, Jesus!’ and turned around and came back. I said, ‘Dr. Rowe, you know you’re going in to check her.’ He said, ‘No. She delivered. That’s all. We’ll go back to Botwood.’

The hard work and long hours fostered interdependence and comradery among the staff of a cottage hospital. They relied on each other. Avery describes it this way: “It was a great experience to be there. It was good being a nurse. We were close.” Hutchings drew a similar conclusion, “I thoroughly enjoyed it when you got into it. Yes and because we were such a small group there, it was like a family.”

The cottage hospital system served the Newfoundland people for almost 50 years but eventually they were turned into health clinics under the auspices of the hospital board in the region. Roche noted the passing of the era of the cottage hospital “… in the 80s. They did not close them, they put them under another place. Like, Grand Falls took over Harbour Breton, and Corner Brook took over Burgeo.”

Public Health Nursing: Before 1934 public health was run by volunteers who were generally the elite of Newfoundland women. One example was the Newfoundland Outport Nursing and Industrial Association (NONIA) started in 1920. Through the sale of knit goods, money was raised to finance the work of nurses assigned to rural districts in Newfoundland. Another volunteer group was the Child Welfare Association established by a group of women in St. John’s. It provided services to mothers, babies and children up to the age of five in St. John’s and surrounding communities. Godden, “I think it was ’39 when I went to Child Welfare to work. I think it was soon after I finished. It was run by a committee of ladies who belonged to the town. They weren’t nurses or anything. Lady Outerbridge was one; she was President of the Association. I suppose that was civic minded. We’d get our birth list from the government, and everybody [born] in the town, we’d have to get a card for them and we visited. And there was five or six nurses. We used to go to the homes and do the immunizations but we had clinics outside like Petty Harbour and Bay Bulls… and Portugal Cove and we had clinics and people would bring their babies to the clinics and have their needle and see the doctor and all that. We also had a children’s clinic – usually up to five years of age but, if they were six, we’d see them.”

In 1934, the Department of Public Health and Welfare established a nursing service, district nurses, to take over functions at volunteer organizations such as Child Welfare. In 1937, the department established a second nursing division, the public health nursing service and freed up the district nurses to do maternity and home care. This was the beginning of community health nursing around the province as we know it today. Likely this was Government’s attempt to set some standards for delivery of community nursing services throughout the island. In 1941 both these divisions were amalgamated.

While all nurses working in Public Health were employed by the Department of Health, there were distinct differences in the work of the public health nurses in St. John’s as compared to those working in communities in rural parts of the island. That is not to say that either group was any more or less important than the other, just that the span of their responsibilities was different as well as the geographic boundaries of their practice. Nurses working in St. John’s had access to resources such as supplies, doctors, an office, and hospitals whereas rural community health nurses, depending on location, often were the sole health care providers who made do with whatever was available. Nurses in St. John’s also didn’t have the transportation challenges of nurses in rural Newfoundland.

Public Health (Rural Areas): Public health nurses in rural Newfoundland traveled under risky and severe conditions to care for their patients. In 1935 Williams entered public health in Placentia Bay; “I enjoyed it but I went through an awful lot. At first when I got there, ’twas all boats – not covered-in boats, just the boat and sometimes they’d throw a sail over me where the water wouldn’t go over me. And then after a few more years, they had a covered-in boat. I had four places. I had Woody Island, Bar Haven, Davis Cove, and Monkstown and, when I’d get to Davis Cove to get to Monkstown, I had to go by horse and buggy or sometimes I had to walk it – that was eight miles. I’d go out to Davis Cove in boat; that would be an hour and a half getting out there. And sometimes you wonder if you were ever going to live to get there – it would be so stormy. My husband’s brother had a boat. But then, if they wanted me in Bar Haven, they’d come down in their own boat for me. Many a time going to Bar Haven, we ran up on a rock. The boat would be stuck up on a rock and, here I’d be, up looking down at the water.” Hutchings on the Northern Peninsula traveled about in much the same way, taking whatever means of transportation available; “When I started to give the immunizations, I did Sally’s Cove in the summer because that was the only time I could get there. From Sally’s Cove to Green Point, I’d go by boat. But St. Paul’s and Parson’s Pond, I did those in the spring and the fall. And, if I couldn’t get there by boat, I walked.” For the public health nurse the opening of a road in her assigned area brought about big changes in health care delivery. Hutchings, “There’s like two parts of nursing: when I was isolated and after the road came. We were isolated until ’62, you couldn’t really plan things. But after the bridge went across St. Paul’s and there was a good bridge across Parson’s Pond going down to Portland Creek, even though it was only a gravel road, you could go and you could say now I’m going to do a set thing.”

The geography of most rural districts was large compared to St. John’s and transportation was very difficult. Often the nurse had to rely on the generosity of the people in each community that she visited for food and lodging. Giovannini in the early 1940s had to travel on long trips to get to her patients. She would stop at homes along the way to get food and was grateful for whatever was offered. “You had to go into any house that would give you a meal. That is right. These people had seal soup and I never tried it before but I ate it and I was still alive.” Hutchings, “Every place you went, you had somewhere there to stay. Nearly every place had someone with a spare room. After I was in awhile, when I’d go to different places I made arrangements with the Department of Health that I would pay them. And pay for my meals.”

Nurses were called upon to do extraordinary things in extraordinary circumstances but with an attitude pervasive in nurses of that generation they adapted to the circumstances without question. Williams, “I delivered a baby in the boat going from Woody Island to Swift Current, off Rattling Brook, on the Mainland. It was called Woody Island Mainland. It happened there was a house [on the boat] and she was down in the house. So when I knew she was in labour, I called out to her husband; he was steering the boat with the big rudder tiller wheel ‘I’ll go in here in the little cove’ he said ‘and anchor and see what’s going to take place.’ And that’s what he did. My dear we were tossing up and down and I delivered that baby girl. I had no facilities [at the clinic] so he took me on to Swift Current and I went on to Come-by-Chance Hospital.” Nurses had to be very self reliant and often circumstances required they make judgements that they felt were in the best interests of their patients but outside the rules. Giovannini, “That is one time when you could use your own discretion and it worked. Well, I left her all night. You see we were not supposed to give any Morphine or anything like that but I did give that to this woman and let her rest. We delivered the baby the next day. If I had kept on with her then, she would have been torn to pieces.”

The daily routine of the public health nurse ranged from fairly routine baby clinics to the extraordinary. Usually there was quite a volume of work which included a variety of responsibilities. Hutchings, “I had a clinic in Cow Head on Monday from 10:00 a.m. to 12:00 p.m. and 2:00 p.m. to 4:00 p.m. Tuesday I went outside the district. I went to Parson’s Pond two Tuesdays a month; St. Paul’s one Tuesday a month, and Sally’s Cove and Green Point the next Tuesday. On Wednesday, I had ordinary clinic in the morning and I had antenatal clinic in the afternoon. This was in Cow Head and mothers in Cow Head would bring their babies the same time as I had antenatal clinic. On Thursday was my school day because I had a lot of schools. I had nine schools. Every term I had to do rapid classroom which was checking their heads for lice and nits and their hands for scabies and that was very important because we did have it. You’d have to write out notes and the ones you picked up with any nits had to stay home and then they had to come back to me and make sure they were okay before I sent them back to school again. In grade one, I would do a complete physical. I would do the height and weight… and their ears. I did ears by whispering. I’d turn them one side and I’d say ‘house, mouse’ and they could pick up what it was and you’d be surprised how many children you could pick up with hearing defects from doing the whispering. And then I did eyes. I did the eye chart… hearing and eyes. And I could tell if the child was underweight by their weight and by their height, okay? Anyhow on Thursdays was my day for schools and I was really busy. Except for one Thursday a month when I did my report and that took me all day. Now if I got a child in kindergarten who was under-weight, well then I would contact the parent… I’d contact the parents and I’ll get them on Maltovol or I’d see them again within a month’s time. And I would do the mothers by going into the home because I found that by going into the home you could see the situation. If you’re in a place very long, after a while you’ll know if the father is well… how they’re doing financially… if they got gardens… or things like this.”

Merrigan, “They used to call it district nurse, but it was all the same. I was in Avondale and St. Joseph’s. We used to visit [the patients] and see how they were. If they had any sores or anything we would dress them and tell them what to do and about the medicine. Miss Squires [the supervisor] was in St. John’s. She used to visit us. If you had an emergency, you had to call the doctor. We visited schools. We gave them their needles, checked for head lice, and made sure that their tonsils were not enlarged. I remember one time I went down to Athens Beach to take out a man’s tooth, and no way could I get it out. But another friend of mine, Miss O’Flaherty, was down in St. Mary’s and she helped me with it. She had training for that where I did not. I was ashamed to meet him [the patient] after! I remember in Avondale, they used to come for Cod Liver Oil and I used to give it to them. Well, I heard after that they were giving it to their horses!”

Home visits were also a part of the public health nurses daily routine but there was nothing routine about the care given each patient nor the relationships that formed between the nurses and their patients. Avery describes one of the patients she cared for as a public health nurse, “There was this man who had cancer of the pancreas. He had a catheter in and assumed that he was going to have this catheter out. But as time went on, he felt he was getting worse and wondered when the catheter was going to come out. He would always ask me when it was coming out and I could not tell him because it was up to his doctor. So, one day I said to him, ‘Matt, I don’t think that they will take out the catheter, this is your lifeline.’ [The catheter went] into his gallbladder; it was bile that was coming out. After I told him that, he looked at me and considered it for a little while and then I believe he understood, and he nodded. After that, when I would go in to change his dressing and wipe around the catheter, he asked me about having it changed. I informed him to ask his doctor. Apparently, they did change it but they really did not want to. I knew that they were not going to do it anymore if this did not work. Anyway, when I would go in to change his dressing, he would be throwing questions at me hand over fist, that I would not know how to answer. When I would leave after an hour of talking to him, I would feel very drained because his last words would always be, ‘Don’t tell Enid.’ Enid was his wife who was always right behind the door waiting for me to come out and ask me what went on. Anyway, I would have to tell her so much and ask her not to tell him. But we worked it all out and toward Christmas he wanted to sell his tools and buy whatever he could for his kids. That did happen and they had a really good Christmas but he was really sick. On Old Christmas Day, January 6, I went in to do his dressing and realized that the catheter was out. Of course, I lifted the catheter with the forceps and he looked at me and nodded his head. He died that night. It was just like he was part of my day; when he died I had nothing to do.”

The nurses’ commitment to their work and patients often meant that family life took a back seat to work. Williams was the only nurse in the area and like many public health nurses around Newfoundland was torn between the patient and her own famil; “I was out this night Christmas Eve. I never got home before 2:00 o’clock Christmas morning, I had delivered a baby. And when I got into bed, my husband said, ‘Now, this is Christmas. You’re not leaving this house Christmas Day.’ I said, ‘Okay.’ We were having breakfast and he said, ‘Don’t you forget what I told you this morning. If anyone comes for you today, you’re not going to go with them. We got a chicken in the oven and a girl there looking after it, so you’re staying home.’ I said, ‘All right boy, I’ll do what you tell me to do.’ I was eating my breakfast and my table went along by the window on Woody Island, and I looked over the hill. And I saw this boat coming in to the wharf and I didn’t say anything, and by and by I saw this man coming up over the hill walking in towards the house. I said, ‘Beaton [her husband], look there’s a man coming down.’ And I said, ‘You know, there’s something wrong for him to come Christmas Day.’ He said, ‘Don’t forget what I said.’ So anyway, a rap come to the door and I went out and he said, ‘I’m from Bar Haven.’ I knew who he was. He said, ‘My wife is dying, nurse, I’m sorry to come.’ I’ll never forget what he said with tears rolling down over his face, my dear! ‘I’m sorry,’ he said ‘I had to come, nurse. I knows you can to do something.’ I said, ‘Come in, sir.’ I said, ‘Beaton, this man says his wife is dying and he wants me to come. What am I going to do?’ My dear! He jumped up from the table. He says, ‘Ethel, when duty calls her danger, be never walking there. Pack your bag and go.’ I saved her. She had a four-month baby [premature]. And he got frightened because she was bleeding. But the baby was only four months… so… [it died]. So that’s where I spent me Christmas Day in Bar Haven. And about 4:00 o’clock in the evening, my husband and his brother and his wife came up in their motorboat to see what was happening. And we went across the Cove to another house and went in there and that’s where we had our Christmas supper. And I had my Christmas dinner at this woman’s mother in law. And she was a cook for the priest in Placentia before she married and, my dear, she had chicken, stuffed, and I had the biggest kind of Christmas dinner!”

Supplies needed by the nurses in rural areas were generally stored in the nurse’s home. Merrigan kept her supplies “… just in a bag that we carried around. We had a shelf whereever we boarded.” Avery’s supply storage changed over time; “When I went to Seal Cove there was no office. When I asked them for a file cabinet they told me to put my things in a trunk. So, I started off with a trunk and a taxi. The trunk would contain files, a book for keeping a record of my work on a daily basis, and a few pages for my travel expenses. We had to give a report every month. At that time, it was just building up a public health system on the shore.” In comparison Hutchings was lucky because she had a clinic; “Now the clinic we had was built by the people, in a building by itself. It had an oil stove and it had canvas on the floor. I had a daybed in the main part of it. I had a waiting room with sort of a bench all the way around built into the wall for people to sit on. No heat. I had a small room that contained the drugs, had a chair with the dental rest on it. I had a washstand, for washing my hands, and a towel rack. I had buckets in the back part for bringing in water from the well. I think that the oil drum was in the clinic in the back. They had shelves in there with things like dressings and pads and extra medications and (equipment) for pulling teeth.”

Like their counterparts working on the coast or in cottage hospitals, the public health nurse was also expected to be available whenever she was needed without expectations of overtime pay or time off. Merrigan describes patients going to her home, “They would come but they were not supposed to. There was an understanding that we could not be called in the middle of the night unless it was necessary. But I never did turn them away.” Nurses were visited for all kinds of problems or to get preventative medications or advice.

Although there was poverty throughout Newfoundland, people who lived in the outports had gardens, and access to the fishery, and hunting. Giovannini shared her perspective of rural life when she was a public health nurse, “But I did go to a place one time and the old lady took me in for the night. Of course, she had bologna and that is about all the poor old thing had. She had it again [the next morning] but then I would not want them to know because I did appreciate it very much. They were very, very kind. [But] the people were not as badly off as some may think. Everybody had their gardens and they had hens and sheep. They would get moose and things like that. They never went hungry; they had their own vegetables and would pick berries. The people were very, very good. They would always bring you some berries, a partridge, or a rabbit.”

Public Health (Urban): Public health nurses in St. John’s functioned quite differently from their counterparts in the rural areas. Community Health in St. John’s was divided into districts which included the surrounding communities such as Portugal Cove. The nurses had greater access to resources, doctors and hospitals. They did not have the same span of responsibilities or the same commuting problems as nurses in rural Newfoundland although very often they did encounter the same health problems particularly in the schools.

Avery, “I came into St. John’s and I worked with Public Health around St. John’s. We would go down by streetcar… down onto Water Street. We would sign in when we got there, pick up our bags, supplies, and so many nurses would get in a car and we would be put off at a certain place. Sometimes you would be put off at a school for a day and do a few things or dressings along the way. You spent most of the time walking. I didn’t really like that but I did learn St. John’s.” Penney, “I really enjoyed Public Health. I did, I must say. Our offices were down behind the old Newfoundland Hotel. That’s where Public Health was situated in those days. And we did five days a week then, and we did night-call. We did night-call in our turn which came up every couple of weeks, every two or three weeks, because there wasn’t that many of us in town. And otherwise you did eight-hour shifts. It was great! Oh yes, that was real living. And we could come home for our lunch, and that was wonderful.”

Public health nurses working in St. John’s faced the poverty that was prevalent around the island but they also faced different social issues than nurses in rural Newfoundland. The city presented its own unique challenges. Moakler was a public health nurse for several districts in the city; “They were so poor and, I wouldn’t say illiterate; I don’t think that’s the word to use, but there was a lot of incest and you had to be so careful. I did get involved in a Family Court thing when I was there. I had a call one night and this mother was screaming on the phone and she said, ‘Come right away. My baby is bleeding.’ So I got up there and this mother was about seven months pregnant I guess… the husband, or her second husband, came home with a few drinks in. I presume he wanted some sexual relationship with her and she refused so he grabbed the three-year old and stepped on her. So I ended up in court with that one. And it wasn’t very nice from what I remember. Last going off… when I came back to public health, I made a few calls [to those same districts] to some of the nurses and it’s so different; everyone there is so educated now and the homes are so beautiful.”

Penney, “I did VD (Venereal Diseases) clinic for two years, and we had to go out and get our contacts. Some would come in and we’d treat them with Penicillin. We had a doctor there. And also in that clinic we did mostly all the different inoculations, for smallpox and that sort of thing. I don’t know why they put it in the VD clinic but that’s where it was.”

Similarly the nurses’ stories reflected the poverty that existed in urban Newfoundland. Many of the poorer women delivered their babies at home in terribly unhygienic surroundings. Penney relates some of the measures used for deliveries. “If they’d come to anti-natal clinic you had a better chance of giving them a little bit of education. Telling them what to get… they’d sew together newspapers for pads for underneath while they were delivering. And then we always had a few [pads] in our bag; we brought our obstetrical bag with us. We always brought some soup and whatnot because sometimes there was no food in the house to give them after they had their delivery.”

Public health nursing in St. John’s had its routine but the nurse didn’t work in the same isolation as did rural nurses. The nurses had each other as well as a support system provided by the Department of Health. There was more use of shift work and nurses were required to be on call the same as cottage hospital nurses they just didn’t live in. They had access to a car and driver if they were called out at night. The call for the public health nurse at night was directed through the hospital so the nurse always had access to the doctor, if needed, but this was unusual. The public health nurse in St. John’s worked very independently and had the authority to make decisions about the treatment interventions. Moakler, “We were on call overnight and, you might be on call every second night and you still had to go to work the next day. We did a lot of home deliveries then so we would have to go with the home deliveries. We had a driver. There were several drivers in the Department of Health and we’d get a call at our home… the people who would need us would call the hospital; the hospital would call our home. We’d go down to our office to pick up the emergency bag and go off with the driver who came for us, and then we’d come back. It could be 2:00 or 3:00 o’clock in the morning, it didn’t make any difference. And then we got up and went to work the next day and never thought anything about it.” Barron, “Now, I was only hired on for five months, and we did call. We did two… one night was the first call, and another night you did second call, so you were on call for two nights a week, but you rarely got called in on the second call, but you were there in case of an assistant. And you did call on the weekends, some things like that. Now you didn’t get paid extra for that.” Penney, “And well we did the schools. We had general clinic, and the patients would come in. But then you had a lot of home visiting, and home deliveries, and they were mainly in the night. Or sick babies at night, and you made your own decisions. You had to decide whether you needed a doctor or not, or whether you need to take them to the hospital or not, but you could do that yourself. And you could also almost diagnose because you could give Penicillin and that, without an order. But you had to, because we didn’t have the doctors. And we’d follow-up the next day.”

Dewling worked with public health from the mid 50s to the mid 60s as a school nurse. “I did home visits and connected with the schools. We did all of the pre school exams, we checked the children to make sure they were healthy and in school and if they were not in school, we went to the home to see how they were. We had a lot of problems in the schools then with impetigo and lice; there was not a morning that you went in that you did not receive a call from one of the schools to go and check this out.”

On occasion the nurse would consult with the doctor before going on call and, if he deemed it necessary, he would accompany the nurse but this was rare. Barron, “I was called one night and… around 12:00 o’clock. Now one of the good things about that… there was always good things… we had a drive. Someone would pick you up and drive you, which was quite different from today. Now up there, there was no telephone service or lights or anything when you’re going out into the woods. So that night, when I got the information, someone got a phone somewhere out there and phoned us. This lady was breathing… she had the symptoms of a coronary. That’s what she sounded like. So you kinda had to diagnose… well you diagnosed. So I called down to the General because there was always a doctor on call, and I thought before I get up there and there’s no phone in that house and I wouldn’t know where to find a phone and have to go God knows where to get a phone. I called down and Dr. Ring… he’s on call and he’s a young doctor from Ireland and I explained the symptoms of this lady and asked him what he would suggest, and he said ‘You come down here and I’ll go with you.’ I would have been up there alone. Even with the doctor and driver it could be scary finding the patient’s home. There was a lady, she said she would have a white bandana on, or a scarf, or something on her head, and she would meet us on the road, which she did. And then we had to follow her. Like you’re going in the woods too, that’s what it was like. I wouldn’t want to do that again. I really was happy to have two men with me… because the driver would come up and pick you up. They were really good. So you walked up to the woods and then you got into this little house. Now that’s the type of thing we did.”

It also fell to the community health nurses to fly out into the smaller communities and collect patients who needed to be flown back into St. John’s or to accompany patients for treatments in larger centers on the mainland. Barron explains what such a flight entailed, “I did a couple of mercy flights, left on a little plane, one engine plane, on Quidi Vidi and we used to go to Corner Brook.” Penney, “And then, too, we did a lot of mercy flights. But now they were earlier on, as I think back, because I remember doing mercy flights and having to go down the cape. A mercy flight is what they called it. For instance, the lady I brought up had a brain tumor… and she was from Torbay somewhere. I took her to the Neuro in Montreal because we didn’t have any facility here for neurosurgery at that time. And then I went one time to St. Anthony and we went down in January and hoping to get back in two days, at the most, and I ended up down there 12 days because of the weather and we had a little Piper Cub is what I went in, a two-seater, and we got down there and we couldn’t get out of it. But that was to bring up a tuberculosis patient who was very ill and who had hemorrhaging and what not and they were sending her up to the San, but we only got back as far as Gander because he cancelled the flight there. One of the pontoons… oh, he had all kinds of trouble with the plane! But so we got on the train from there and came in and brought her to the San, and she had what they used to call ‘millery Tb’ in those days. So she died actually. This was before Confederation.”

Griffen also did mercy flights; “Yeah, when I was in St. John’s, I used to go out and pick up passengers… patients from around the coast. It used to take off from Octogon Pond in St. John’s. The pilot would have the plane but I’d be the nurse who would be taking the patients back. And you ran in some little places and, honest to God, you’d think you were from outer space. The whole crowd would be out staring at you. It would be just when they needed somebody to go out and pick up a patient. All around the coast, everywhere. I remember coming in to Gander one night; we were going to land in Gander, and it was dark. You couldn’t land after dark, and I remember the pilot said to me, ‘What are we going to do with her, the woman?’ I said, ‘I got nothin’ to give her, but I’m more worried about what you’re going to do with us.’ Because, he said, ‘Have you ever been to Crosbie’s Cabins?’ and I said, ‘No.’ He said, ‘I think that’s where we’re going to have to go tonight.’ I said, ‘Well I’m more worried with what you’re going to have to do with me; I think I’d like to land in Gander tonight, myself!’ We did make it to Gander but it was an experience! That would have been… let me see now… it was about ’61 or ’62. The plane from St. John’s would pick them up and bring them mostly to Gander, the nearest hospital. They’d be very sick, half dead when you picked them up. Sometimes there were maternity [patients] that were having complications but not ready to be delivered.”

Public health nurses were well received and respected in the community. As the public health nurse moved around her district she was easily recognized by her uniform. Avery, “In the winter we had a suit with a navy blue jacket, white blouse and a skirt. While we were doing clinics we had white aprons we would wear. In the summer for a while, we had light blue dresses and later, navy. They were rather nice and lightweight. We wore hats during most of my time; the last summer hat that we had, nobody could wear it. It was really round like a little pancake on your head. Everyone knew who I was.”

Nursing in the community was challenging and varied in scope whether it was public health nursing in the rural or urban areas, a nursing station or a cottage hospital. This group of women had a clear notion of their role, ‘to serve their patients’ and did so without question. They were independent, versatile women, committed to their work and the people. Their recollections tell of the measures they were willing to take to care for their patients. But what choice did they have? As many stated, ‘There wasn’t always a doctor.’ Without these nurses, many areas and people around the island would have had no access to health care. Their stories clearly demonstrate the importance of the nurse to health care delivery in Newfoundland and Labrador.

Grace Hospital School of Nursing graduating class of 19ffl with three of their teachers, all of whom were Salvation Army Officers.

St. Clare’s School of Nursing graduating class of 1947.

General Hospital School of Nursing graduating class of 1948.

Ethel Williams in navy uniform worn by Public Health Nurses in the winter.

Jane Hutchings on the steps of her clinic in Cowhead. Note her uniform included slacks to accommodate the northern climate and modes of transportation.

Ruby Dewling and classmate with surgical patients. Patient stays in hospital were often so long that it was not unusual to move the patients outside on warm sunny days.

Elizabeth Avery in summer uniform worn by Public Health Nurses.

Ethel Williams in her clinic on Woody Island with the stock of supplies and medicines used by the public health nurse in rural areas.

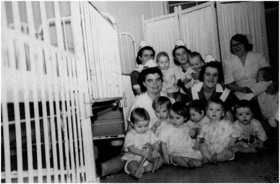

Staff at the Waterford Manor where healthy babies of unwed mothers were housed.

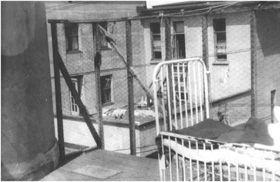

Nurse taking a patient’s vital signs on the veranda of the Sanatorium. Fresh air was important for the treatment of tuberculosis.

The back of the Sanatorium showing the verandas where patients were placed during the day to get fresh air.

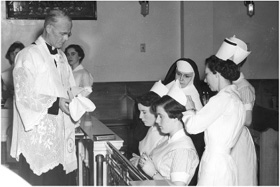

Capping ceremony taking place six months after entering St. Clare’s School of Nursing; a milestone for the student nurse.

Marcella French and colleague at the nurses’ station.

Griffen holding a child at the Sunshine Camp, where children went to recover from polio.

The King Edward V Residence. Nursing students reportedly hung their hats and gloves in the trees when leaving for a social evening downtown and picked them up before returning to the residence.

The roof where nurses would suntan on warm days.

Nurses and patients at Orthopedic Hospital.

Marcella French and classmates in 1939.

Ashbourne and classmates in 1942.

Party for Phyllis Barrett upon her resignation as Director of Nursing because of pregnancy.

Higgins and Dewling on Alexander Ward, the pediatric unit of the General Hospital.