If misery truly does love company, it was fitting that Mickey and Helen sailed for China together the first week of March 1935. Both sisters were downcast as their ship steamed out of San Francisco. It was not until they were at sea that the Japanese captain announced that the ship was not going to Shanghai, the Hahn sisters’ destination; the Cichibu Maru was instead bound for Yokohama, where they could make connections. Mickey and Helen were not much concerned by this unexpected change of plans. They were happy just to be going somewhere, anywhere.

Mickey’s affair with Eddie Mayer had come crashing to an inglorious end; Helen was dejected after a big argument with Herbert. It was because of this and because Helen was on her first trip abroad that the women traveled first class. The change was one Mickey enjoyed, especially when she and Helen met a Japanese-American businessman who introduced them around the ship and then entertained them royally in Japan.

Everyone Mickey and Helen met during the three-week stopover in Japan was friendly and cordial, and so the sisters were truly sad that they could not stay longer in Japan. But they had to go; a family friend was waiting for them in Shanghai. Mickey planned to stay there a few weeks before traveling on to Africa on her own. Helen had booked passage home to New York on a ship that was due to sail June 12. It was in late April when the Hahn sisters left Yokohama for China aboard a “dirty little tub” of a mail ship, as Mickey termed it.

“The mind of a traveler has only one spotlight, and it is always trained on the present scene,” she later wrote.1 As a result, Japan seemed much less benign from their new vantage point. There was a good reason: in the spring of 1935, long-simmering hostilities between Tokyo and Peking had boiled over into war. Mickey and Helen were astounded that the Japanese they had met were the same people whose army had invaded the northern Chinese province of Manchuria, where soldiers were engaging in an orgy of raping and pillaging. Mickey could only agree with Helen who said, “Over there [in Japan], we saw everything in a misty light. Here, [Japan] is all much more harsh.”2

Her disillusionment was nurtured by the seductive charms of Shanghai. The city, then known as “the Paris of the Far East,” is situated midway up China’s coast. It is thirteen miles inland, on a tributary of the mighty Yangtze River then called the Whangpoo. Shanghai, the world’s fifth largest city in 1935, was a bustling port and commercial center. In the minds of Westerners, the very name Shanghai conjured up images of mystery, adventure, and romance. “Life there was a highly charged affair, what the Chinese called ‘jenao,’ a perpetual ‘hot din’ of the senses,” British historian Harriet Sargeant wrote.3 The writer Aldous Huxley summarized the essence of Shanghai as “Life itself … dense, rank, richly clotted … nothing more intensely living can be imagined.”4

Shanghai was trendy in the mid-1930s. It was the place to visit if you had the time and money. No world cruise was complete without a stop in Shanghai. It was said that Wallis Simpson, clad only in a life preserver, had posed there for a series of dirty postcards. Charlie Chaplin and Paulette Goddard, his wife to be, had holidayed in Shanghai in 1936. Mussolini’s son-in-law, Count Galeazzo Ciano, went there to chase women in the city’s legendary dance halls and nightclubs. Even Hollywood jumped on the Shanghai bandwagon, setting several popular films against the city’s backdrop; among them were a Busby Berkeley musical and the 1932 melodrama Shanghai Express, starring Marlene Dietrich. (“It took more zan vun man to change my name to Shanghai Lily.”)

Shanghai’s superheated economy made it the Hong Kong of the early 1930s. American journalist Vincent (Jimmy) Sheean wrote that Shanghai was the place par excellence for two things: money and the fear of losing it. This suited the foreigners who were there for the proverbial “good time, not a long time.” Rice was cheap, so cheap that as far as Westerners were concerned, it was almost free. Cheap rice meant cheap labor, and that meant cheap prices. With the exchange rate at three Shanghai dollars to one American dollar, the cost of most consumer goods and services was staggeringly low, even by depression-era standards in the West. Mickey Hahn, like everyone with foreign currency to spend, lived a lifestyle that she could only have dreamed of back home. The material for a tailored suit sold for about $1 (U.S.); dinner in a good supper club was the same price, with the floor show an extra $1.50. Westerners living in Shanghai raised hedonism and conspicuous consumption to gaudy art forms.

There were no taxes of any kind, and foreigners came or went freely, because passports were not needed. As a result, Shanghai was a mecca for refugees, adventurers, arms dealers, entrepreneurs, missionaries, spies, and tourists. Many who came also stayed, and so by the late 1930s, there were 60,000 foreigners among Shanghai’s four million residents. “One never asked why someone had come to Shanghai,” one British observer noted. “It was assumed everybody had something to hide.”5

Joining the British, French, and German businessmen—the taipans—were the Japanese, who arrived in the 1890s. They set up industries that took advantage of the abundant supply of cheap labor. Next came thousands of White Russians, the royalists who fled the 1917 Bolshevik revolution. Then came boatloads of German and Austrian Jews, the victims of Nazi persecution. The White Russians and Jews were stateless, meaning that they were legal nonentities. As such, they were subject to Chinese law, courts, and prisons.

It was the British who set the tone in Shanghai’s foreign community, both morally and socially. Sinophobia was rampant, although Mickey noted, “Not since I left the U.S. have I heard [Chinese] referred to as ‘Chinks.’”6 The British condescendingly considered that word a crass Americanism. In the British vernacular Chinese males of all ages were routinely referred to as “boys”—in the same derogatory way that whites in the U.S. South used the word when talking about blacks; Chinese women were seldom referred to at all. Mickey recalled a story one Englishman told her about his visit to San Francisco, where he had encountered a Chinese “boy” who did not get out of the way as he walked along the street. “Why, in a civilized country I’d have flayed the bastard!” the Englishman sputtered.7

Despite such unabashed racial discrimination, Chinese people flocked to Shanghai. Rich and poor alike were drawn by the lure of jobs, fast money, and contact with Western culture; Shanghai was where the action was. In the late 1920s and early 1930s, the city briefly displaced Peking as the epicenter of China’s cultural and intellectual life. Although China’s rulers, army leaders, and conservative intellectuals frowned, there was little they could do about it or about “the white men behind the desks” who ran Shanghai. To make the best of a bad situation, Chinese authorities granted control of areas of the city—called “concessions”—to each of the intruding nationalities. In total, foreigners ruled more than 60 percent of Shanghai’s twenty square miles of territory. This area, the International Settlement, was governed by an elected council representing foreigners in each concession. Peking appointed a mayor to run the Chinese sections of the city, which were bustling, squalid, and poor.

This was the backdrop into which Mickey and her sister Helen stepped when they arrived in Shanghai from Japan that spring day in late April 1935. Their ship anchored in the harbor, among passenger liners, freighters, and naval ships from twenty nations. A steam launch ferried passengers the two miles into the city because the mouths of the Whangpoo and Yangtze Rivers were too clogged with brownish yellow silt to allow the big oceangoing ships any closer. Miles out in the blue Pacific, beyond the horizon, the mud that was discharged by the Yangtze announced the proximity of land.

The Whangpoo River at Shanghai was jammed with Chinese junks and houseboats that anchored just off the Bund, the city’s bustling main street and promenade. Here Mickey and Helen saw long blocks of shops, Western-style apartment buildings, and commercial towers that housed the air-conditioned offices of the city’s taipans. As they stepped ashore, the Hahn sisters were assailed by a dizzying kaleidoscope of sights, sounds, and smells.

“On the Bund at midday human beings became insects again,” British writer Harold Acton once observed.8 “Stand [here] any day … and watch the variety of traffic that passes under the signals of a tall, bearded Sikh traffic policeman,” advised another contemporary account. “Electric tramcars, loaded buses, and trackless trams, filled to all available standing room; motor cars and trucks … wheelbarrows that trundle along with tremendous loads: coolies turned beasts of burden, bearing bales and baskets of incredible weight: great two-wheeled trucking carts, with as many as six or eight perspiring coolies straining at the pull ropes; rickshaws … bicycles, carriages, pedestrians—the whole contrasting procession passes.”9

Bernadine Szold-Fritz, an old friend of their sister Rose’s from Chicago, met Mickey and Helen on the pier in Shanghai. A divorcée, Bernadine later married a wealthy American stockbroker named Chester Fritz and in 1935 was one of the leading tai-tais (taipan wives) in Shanghai society. There were few prominent American visitors who did not have a letter of introduction to Bernadine or who did not seek her out. Not only was she herself a renowned hostess; she was a regular at the constant whirl of parties, balls, club meetings, and other events that made up the local “social scene” in Shanghai’s tightly knit foreign community.

British influences dominated, and there was no shortage of snobbery, but a “colonial” atmosphere prevailed, meaning that people socialized in Shanghai who would never have spoken two words to each other in polite London society. “Occasionally an enterprising tai-tai would attempt to introduce a new note into Shanghai’s social life,” one observer noted. “Some American ladies pioneered, although not too successfully, in inviting both Chinese and foreigners to their homes. One of them, [Bernadine] Fritz, who gave parties every Sunday night, prided herself on presiding over Shanghai’s only ‘salon.’ Foreigners mingled with prominent Chinese.… But the hostess was too extravagant (she always wore a turban) to be taken seriously.”10

Bernadine Fritz welcomed Mickey and Helen to Shanghai, then immediately whisked them off to one of her famous dinner parties. The other guests at the table that evening included a French count and his Italian wife, a Pole who was a naturalized French citizen, and a Chinese customs inspector. Mickey and Helen were quizzed about what was happening in the United States and about their views on China’s “troubles” with Japan. The Hahn sisters became prizes in a social tug-of-war. “There were feuds between the cliques, and I was soon mixed up in them,” Mickey recalled. “The arty group battled for my scalp with the plain moneyed class as long as I was a novelty, and in the end nobody won at all, or cared.”11

In New York, Mickey had been an unemployed writer with no money, a broken heart, and a vague future. It was different in Shanghai. There she was a somebody, and it felt good. Mickey’s free spirit and lively wit became the talk of the foreign community. With the money she carried and with the kindness of strangers, Mickey realized that she could live a lifestyle that back home she could only dream about. The company she kept was certainly better.

While attending one of Bernadine’s amateur theater nights, Mickey and Helen met Sir Ellice Victor Sassoon, the most powerful of Shanghai’s taipans and one of the wealthiest men in all of the British Empire. “I thought him unusually quick and witty, especially for a businessman,” Mickey said.12

“Eve,” as his family knew him (because of his initials, E.V.), had been born in Baghdad to a prosperous Jewish family who claimed descendance from King David himself. The Sassoons—the “Rothschilds of the East”—were unique in other ways. As Sassoon family biographer Stanley Jackson noted, other merchant families amassed larger fortunes, “but none … more dramatically spanned two worlds, oriental and Western, or generated so many virtuoso talents outside the commercial sphere.”13

Sir Victor—as Mickey affectionately knew him—was a renowned ladies’ man. He was tall and athletic, with handsome dark eyes. Sir Victor sometimes sported a monocle in his weak right eye, but there was nothing foppish about him; he was handy with his fists. A strong swimmer, Sir Victor also excelled at tennis and golf and loved dancing, the theater, and horses. His “Mr. Eve” stable was one of the world’s largest and most successful in the 1930s.

Another of his great loves was photography. He was an avid amateur shutterbug. Sir Victor invited the Hahn sisters to visit his private studio. There he showed them a big album in which he kept the nude photos he had taken of many of Shanghai’s most beautiful women. When Sir Victor asked Mickey to pose for him, she readily agreed. Mickey was flattered that he had asked her and not Helen; deep in Mickey’s subconscious there simmered the rivalry between the sisters that had its roots in the resentment Mickey had felt over Helen stealing her boyfriends. “Sir Victor didn’t ask to photograph Helen, and she kept saying, ‘I wish I had a good figure.’” Mickey recalls. “Sir Victor just smiled. ‘But you have such a nice nature,’ he said.”14

It was not long before more than photos had developed; Mickey and Sir Victor became intimate friends, who each got something out of the relationship. For Mickey, it was material “favors,” one of which was a shiny new blue Chevrolet coupe that she began using on weekend trips. For Sir Victor, a committed bachelor, it was the ego boost of having the companionship of one of the few attractive, intelligent, and single American women in Shanghai. Money and ego aside, there was also an element of genuine affection between Mickey and Sir Victor, two kindred spirits in a faraway place. It did not hurt that the Hahns also had Jewish blood.

Everyone in the foreign community scrambled to curry favor with Sir Victor and wrangle invitations to the lavish parties he threw in the penthouse of his Cathay Hotel or at his home. A photographer from the North-China Daily News, the city’s British-owned English-language daily newspaper, would invariably appear. The next day’s paper would be filled with photos of those who had attended.

Despite his social standing, Sir Victor was regarded with haughty disdain by many in the foreign community. The prevailing sentiments were voiced by British writer Sir Harold Acton, who dismissed Sir Victor as “a very agreeable fellow if rather a Philistine.”15 Some people resented his money, some his power or his well-deserved reputation as a “lady chaser.” Some disapproved of the fact he had moved his business from Bombay to Shanghai in 1931 to escape British taxes. Still others disliked Sir Victor because he was Jewish, or because he dared to socialize with Chinese. As Mickey recalled, “[He] … was not well liked by most young men. They’d set up a chant when he appeared in a bar: ‘Back to Baghdad! Back to Baghdad!’”16

He was well aware of how people regarded him, so Sir Victor delighted in delivering occasional reminders to his “friends” of the power that he wielded over them. At one of his parties, he poured a bottle of crème de menthe down the back of a distinguished British visitor’s suit. Another time, he held a costume ball at which guests were invited to dress as circus animals. When they did, Sir Victor made a grand entrance dressed in a ringmaster’s costume.

Given her relationship with Sir Victor and the many other ties she had developed, Mickey decided to remain in Shanghai longer than planned. “Helen left early this morning,” Mickey told her mother in a letter dated June 12, 1935. “I felt slightly dismayed as she disappeared in the distance and more so when I discovered that she had left her white coat, which I’ll send over with somebody else on the next boat.”17

Sir Victor Sassoon’s portrait of the Hahn sisters, Helen and Mickey, in profile, Shanghai, 1935.

Courtesy Emily Hahn Estate

Mickey went on to report she was being “whirled around in the usual senseless (pardon me) activity” of Bernadine’s amateur theater group. “Tonight is a charity ball, and I am dancing in the American part of the entertainment; a barn dance in tennis shoes and checked gingham with hair ribbon.”18

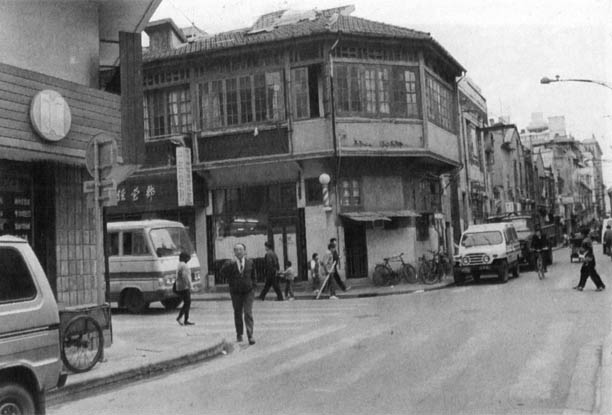

Following Helen’s departure, Mickey rented a two-room flat on the ground floor of a Chinese bank building. The living-sleeping area was painted dark green. Over three of the walls, some artistic person had erected a silver metallic grillwork that was meant to resemble bamboo trees. Stars and a crescent-shaped moon were painted on the ceiling. Through the grimy windows, Mickey looked out on busy Kiangse Road, in the city’s red-light district. Whatever the flat lacked in elegance it more than made up for in affordability, especially because Mickey now had a job. She found temporary work as a reporter with the North-China Daily News. She was hired to fill in for a woman who was away on her honeymoon. By the terms of the Land Regulations laid down by the Chinese government, all white females who worked in Shanghai’s International Settlement were supposed to be signed on “at home.” This meant they were hired on contract and came to China under the sponsorship of the firms that had hired them. There were exceptions, of course, particularly if one knew the “right person.” Mickey had no trouble obtaining the necessary permission.

The very photogenic Sinmay Zau, circa 1935.

Courtesy Dr. Xiaohong Shao

Her job at the Daily News was busy, although not terribly challenging. Mickey’s assignments provided her with lots of opportunities to meet and socialize with a cross section of people. She was still seeing Sir Victor, but she also fell in with a circle that included a half-dozen single men from various foreign consulates and legations. Her social life never lacked for excitement or variety. At one of the group’s dinner parties, she met an inquisitive Englishman named McHugh. Mickey knew he was an intelligence agent, and so when McHugh began questioning her about her friends, she spun him an elaborate tale about her meetings with “bearded Russians and Communist plotters.” McHugh listened intently, and after he had gone home to write it all down, Mickey and her friends had a good laugh at his expense. When she next encountered McHugh a few weeks later, he grabbed her by the lapels and shook her. When he had reported his conversation with Mickey, his superior had scolded him; British intelligence had a thick file on one Emily (“Mickey”) Hahn, and across the front of it someone had written the words, “Disregard Miss Hahn’s entire story.”19

Bernadine and other wagging tongues in the foreign community applied no such caveat to tales of Mickey’s escapades. “Shanghai gossip was fuller, richer and less truthful than any I had ever before encountered,” Mickey later wrote.20 The more people talked about her, the more outlandish her behavior became. Mickey’s relationship with Sir Victor provided ample grist for the gossip mill, but it was her love affair with a well-to-do Chinese gentleman poet and publisher that scandalized the foreign community. Even her most tolerant friends warned Mickey that she was “crossing the line” by taking a Chinese lover. In Mickey’s mind, that only made it all the more deliciously wicked—and therefore appealing.

As it looks today: the building at 348–349 Kiangse Road, Shanghai, where Emily Hahn lived from June 1935 to the fall of 1937.

Gulbahar Huxur