A first baby—like the proverbial check that’s “in the mail”—arrives when it’s least expected, so for five days after entering the hospital, Mickey waited. Her contractions began several times, only to stop each time as unexpectedly as they had begun. “I would just halfway get there and then have to start all over again,” Mickey wrote in a letter to Helen.1 Finally, two weeks past her anticipated due date, Mickey’s doctor, a British missionary named Gordon King, tried to induce labor. When that failed, he performed a cesarean section.

“How much of this do you want to feel, before we help you?” he asked.

Mickey was taken aback. “Did you think I was doing all this to write a book about it?” she replied.

King shrugged. “Why yes,” he said. “Isn’t that the idea?”2

The cynicism of King’s remark angered her; however, the more she thought about it, the more Mickey felt that maybe he had a good idea. She resolved to make the best of the situation. “I thoroughly enjoyed the operation,” she quipped. “It was my ideal of an experience: something happened to you that you can watch without feeling it.”3

All went smoothly, and the baby arrived late on the evening of October 17, 1941. The child was a tiny five-and-a-half-pound girl whom Mickey and Charles named Carola Militia Boxer. When the nurses took the baby away to clean and dress her, Mickey remained on the operating table while her doctor removed a large fibroid tumor from her uterus. While such lumps are common and usually benign, they can cause severe pain, abort a pregnancy, or even pose a risk during a delivery. “You’re lucky,” the doctor told Mickey. “We’d have had to have that out within a month anyway, and the child couldn’t have survived a normal birth.”4

Afterward, as Mickey lay in her hospital bed surrounded by baskets of flowers sent by Charles and various friends, she drifted in and out of consciousness. Her abdomen ached, and her sleep was troubled by horrible recurring nightmares. One moment, Mickey dreamed she was back in Chungking in an air raid. The next, she dreamed of Carola’s face floating in the clouds. The baby was dying of starvation, her withered body shrinking ever smaller, until finally all that was left was a huge pair of eyes. Babies died every day in China; Mickey had watched them. She was determined that hers would not suffer the same fate.

Mickey’s month-long hospital stay was sheer torture. She quickly tired of being “bullied” by her nurses and of adhering to the hospital routine. Mickey worried that if war with Japan broke out, Charles might be posted elsewhere. If he was, she knew she might never see him again. The thought was unbearable. Mickey announced she was going home. She ignored her doctor’s advice, packed up Carola on November 15 and left. Despite a sore abdomen and a host of worries, life suddenly didn’t seem too bad. Mickey had decided everything might turn out all right after all. She found a part-time teaching job, partly because she needed the money and partly because working was a boost to her self-esteem. Teaching, she observed, “is a cheap form of maintaining a superiority complex.”5 Carola stayed home in the care of her Chinese amah, while Mickey resumed her career. She was late for her first afternoon of classes when she drank too much at a celebratory lunch and got lost on the way to the school.

Having a job again was just one reason Mickey’s mood brightened. There was another: the renewed air of optimism in the colony. A new British governor, Sir Mark Young, had arrived in Hong Kong, as had reinforcements for the garrison, a regiment of brash young Canadian troops. Mickey began to relax. Perhaps she could feed and look after a child on her own. Most people in the colony were preoccupied with their own problems, so Mickey did not even face the social ostracism she had anticipated. Nevertheless, Mickey herself was having sober second thoughts about becoming a mother. In a letter to Sir Victor Sassoon in Bombay, Mickey explained that she was already agonizing over how to one day tell Carola the circumstances of her birth. Sir Victor advised Mickey never to do so. “We look at it from different angles,” he explained in a letter of congratulations. “No one has the right to handicap the child from the start deliberately. I cannot see the child will think it better when she grows up to know that the action was deliberate, but you seem to [disagree]. Maybe you think she will be so superior to others of her generation that she shall not complain at being handicapped; all I hope is that she will be conceited enough to think so. You see, you look on it from the selfish personal point of view. I, with all the advantages possible [in] an unhappy childhood, and cannot forget it.”6

Mickey with the newborn Carola, Hong Kong, October 1941.

Courtesy Emily Hahn Estate

As Mickey puzzled over her situation, other aspects of her life were clearer. For one, the uncertainties between her and Charles were resolved. He received a letter from Singapore a few days after the baby’s birth announcing in “ladylike tones” that Ursula had filed for divorce. Mickey’s Chinese marriage to Sinmay was not recognized by British law, so the only remaining obstacle to Mickey and Charles’s marriage was a legal requirement that they wait six months. “I suppose we’ll marry,” Mickey told her friend Vera Armstrong. “It doesn’t seem to matter any more.”7

Those words were puzzling and prophetic, for three weeks after Mickey’s return home from the hospital, the international situation deteriorated quickly. The governor, Sir Mark Young, ordered the mobilization of all Hong Kong volunteers, and the military garrison was put on alert. Meanwhile, in Washington, what one historian termed “the ponderous diplomatic ballet” that had been going on between the United States and Japan took a dramatic turn. News bulletins reported that two Japanese envoys were meeting with President Roosevelt in a last ditch effort to avert war. Acting on a suggestion by one of the envoys, on December 6, 1941, Roosevelt sent Emperor Hirohito a personal appeal for peace. “The son of man has just sent his final message to the Son of God,” Roosevelt told White House dinner guests that evening. The President had written: “Both of us, for the sake of the peoples not only of our own great countries but for the sake of humanity in neighboring territories, have a sacred duty to restore traditional amity and prevent further death and destruction to the world.”8

There was no indication that the Emperor shared Roosevelt’s sentiments or that he even read the conciliatory message. The Japanese fleet had already put to sea en route to its rendezvous with history. Late that same night, as Roosevelt and his commerce secretary Harry Hopkins sat talking in the Oval Study, a courier arrived with some intercepts of decoded Japanese radio messages. Roosevelt learned that Tokyo had rejected his latest peace proposal. It was no longer a case of “if,” only of “when” the fighting would begin. Roosevelt also knew from naval intelligence reports that the Japanese fleet had put to sea. The world held its breath and waited, but not for long.

Just a few days earlier, on December 3, Hong Kong’s commander Christopher M. Maltby and his staff officers had toured the border area north of the colony. Despite reports from British spies in China that Japanese troops were massing for an attack on Hong Kong, Maltby continued to ignore the warnings. He was confident that the six battalions under his command—two British, two Indian, and two Canadian, totaling about 13,000 men—could ward off any enemy offensive. As late as December 7, dispatches sent from Hong Kong to the War Office in London stated that rumors of a Japanese military buildup were “certainly exaggerated and have the appearance of being deliberately fostered by the Japanese who, judging by their defensive preparations around Canton, appear distinctly nervous of being attacked.”9

Charles was much less sanguine about the situation. He had spent a lot of time working with and observing the Japanese army—particularly the 38th Infantry Regiment, which happened to be one of the enemy units poised at the border. Charles knew that while some of the Japanese troops appeared to be shabby and ill equipped, appearances were deceiving; this was an enemy not to be underestimated. Charles was filled with a profound sense of foreboding. When he arrived at Mickey’s flat for lunch on December 6, a photographer was snapping pictures of Mickey and the baby. Charles posed reluctantly. Later, he told Mickey how he had spent the previous night at a dinner party hosted by Lieutenant General Takashi Sakai, commander of the 23rd Army, the Japanese occupying force in the Canton area of southern China. Everything had seemed “normal,” yet Charles had a nagging sense that his hosts were being almost too cordial, too jovial; he could not help but wonder if this was the proverbial calm before the storm.

Mickey invited several friends for drinks on Sunday evening at Charles’s flat. They included Colin MacDonald, who was the correspondent for the London Times, and Dorothy Jenner, “an amusing Australian newspaperwoman,” as Mickey described her.10 Jenner had been a silent film star before she began writing under the pen name “Andrea.” Charles, who was supposed to spend the night at headquarters, ignored the orders and tried his best to be cheerful. The guests stayed for dinner even though it was a subdued gathering. “Charles’s uniform and the fact that he sat in front of the radio most of the evening, had a dampening effect upon our spirits,” Mickey wrote.11

Dorothy Jenner initially declined when the vanilla soufflé came around for seconds. “You’d better take some more. You never know when you’ll next be offered vanilla soufflé,” Charles had cautioned. Many times over the next three and a half years, Jenner would remember those words and how delicious that extra serving of dessert had tasted; like all Hong Kong civilians who were interned by the Japanese, Jenner starved. By the time of her liberation in the summer of 1945, her once “ample figure” had shrunk to just eighty pounds.12

Mickey stayed behind after the guests left Charles’s flat about midnight. They listened to a radio broadcast from Tokyo at 4 A.M. on December 8, Hong Kong time, and an hour later Mickey went home to feed Carola. It had been raining, and the air on the Peak that Monday morning was clear and cool. It was going to be a nice day, Mickey remembered thinking. How wrong she was! In the immortal words of President Franklin D. Roosevelt, it was “a date which will live in infamy.”

Mickey was feeding the baby when Charles called at about 6 A.M. After Mickey’s departure, he had gone downtown to “the Battle Box,” the British military’s underground bunker on Queens Road Central. There, thirteen stories below street level, Charles sat down at the radio set to relieve Major “Monkey” Giles of the Royal Marines, the senior naval intelligence staff officer in Hong Kong. Giles had spent the night monitoring Japanese radio broadcasts. At 4:45 A.M., Charles was listening when a voice on Radio Tokyo interrupted some classical music to announce that units of the Japanese Imperial Navy and Air Force were attacking American and British forces in the Pacific. Charles roused Giles, who had just gone to sleep on a camp cot in the radio room. “The war’s started. You don’t want to miss it, do you?” he shouted. Charles then rang Major General Maltby’s aide to alert him to the news: that morning (Hong Kong, on the other side of the international date line, is a day ahead), just before first light on December 7 in Hawaii, 366 Japanese warplanes had taken off from aircraft carriers for a devastating sneak attack on the U.S. naval base at Pearl Harbor. By the time Charles roused the alarm in Hong Kong, the “Battle of Hawaii,” as the Japanese media dubbed it, was already over.

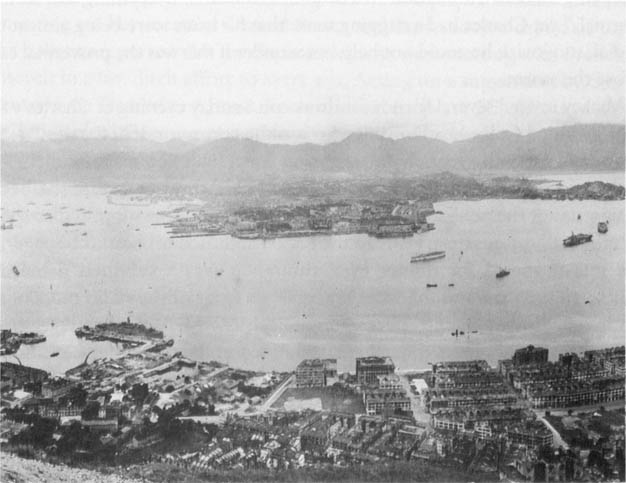

The view from atop the Peak, looking northward across Hong Kong harbor toward Kowloon, circa 1940.

National Archives of Canada, Neg. #PA161884

The word “battle” was a misnomer, for the American forces at Pearl Harbor had been taken completely by surprise. At five minutes before 8 A.M. on that sunny Sunday morning, most people were still having breakfast or were snuggled in bed. Their peace and quiet was shattered by the angry drone of warplanes, and then the cacophony of falling bombs, explosions, and gunfire. All hell had broken loose. By the time the Japanese pilots returned to their carriers two hours later, the United States naval base was in ruins; 2,330 Americans lay dead or dying amidst the flaming wreckage. Seven battleships had been sunk or badly damaged, and 188 military aircraft had been destroyed. Japanese losses were twenty-nine aircraft and sixty-four crewmen.

Within hours, the Japanese launched a series of surprise attacks on other American bases at Guam, Wake Island, and the Midway Islands, and troops were landed on the Malayan coast near the British colony of Singapore. “The balloon’s gone up,” Charles told Mickey when he called her at 6 A.M. Hong Kong time. “It’s come. War.”13

It was two hours before the general alarm sounded throughout Hong Kong on what the British refer to as “Imperial Rescript Day”—the day the Japanese Emperor issued a proclamation declaring war on Great Britain. During that time, wild rumors swept the colony. One of the first things that Mickey did after Charles’s call was to ring Hilda Selwyn-Clarke. Charles had arranged that if war began Mickey and Carola would move in with Hilda and her husband, Selwyn Selwyn-Clarke, Hong Kong’s chief of medical services. Their spacious home was higher up on the Peak than Mickey’s flat, and presumably it was safe from any “unpleasantries” that might occur. At 8 A.M., Charles called again to assure himself that Mickey had made plans to move. As they were talking, the peace of the Hong Kong morning was pierced by the wail of air-raid sirens. Then from the direction of the harbor came sounds that Mickey knew all too well from her time in Chungking: the whump of falling bombs and the tata-tata-tata of antiaircraft guns. Mickey raced out onto her terrace. Across the harbor, she saw flames and smoke rising above Kowloon. Japanese warplanes from Canton, 125 miles northwest, were attacking the RAF squadron at Kai Tak Airport. Mickey’s neighbor, a British man to whom she had never spoken before, was puffing on his pipe as he surveyed the scene.

“Good morning,” Mickey said. “Here it is.”

“Yes,” he replied, shaking his head in disbelief. “Japan’s committed suicide.”14

Mickey, like Charles, was not quite so sure. Her doubts proved to be well founded, for that initial air strike was one of the keys to the success of what the Japanese had planned. In bombing the runways and hangars at Kai Tak, the Japanese had destroyed five aging RAF planes: two Walrus amphibians and three Vickers Wildebeeste torpedo bombers. All were more than ten years old, slow and useful only for reconnaissance flights. The Chiefs of Staff in London had refused requests for a fighter squadron for Hong Kong because the airport there was considered an easy target. As a result, the outdated planes based there were no match for enemy fighters. The RAF pilots were under orders to fly them only at dawn or dusk when the light was poor, and only if there was “an opportunity” to attack an enemy ship. How the pilots were to know an opportunity existed unless they flew is unclear.

Major General Maltby had assumed that Japanese troops posed the main threat to Kai Tak Airport, and the only enemy units in the area being in occupied China, fifteen miles north of the colony, he placed his faith in the Gin-drinkers’ Line to discourage any attack. Named after a bay, the eleven-mile-long network of slit trenches, barbed wire, and pillboxes was strung out across the rugged, sparsely populated land along the Chinese border. Japanese spies had pinpointed the gaps between the line’s defenses, rendering it useless, even if the Japanese had chosen to attack Kai Tak Airport by land. No matter, it took the enemy planes just five minutes to destroy the runways, facilities, and most of the planes there. Given the raid’s success, Hong Kong’s outnumbered defenders were now sitting ducks for enemy aircraft. Triumphant Japanese pilots swooped low over Kowloon after their raid. They dropped bundles of leaflets that warned of bloody consequences unless the colony surrendered.

Hong Kong, fall 1941: (l–r) Agnes Smedley, Mickey, Hilda Selwyn-Clarke and daughter Mary, Margaret Watson Sloss.

Courtesy Agnes Smedley Papers, Arizona State University

From her vantage point, Mickey watched as the planes roared off into the northwest sky. She returned to her flat feeling dazed and shaken. Inside, she found her wash amah, Ah Choy, folding laundry in the bedroom. “You scared, missy?” she asked softly.

“Nooooo,” said Mickey. “You’re not scared, are you, Ah Choy?”

“Yes,” the woman admitted. Then she began sobbing.

Mickey walked slowly over to Carola’s crib. The baby had remained fast asleep through all the excitement. No, Mickey decided as she stood there, she was not yet frightened for herself; she was terrified for her baby. Mickey had seen the ferocity of the Japanese army at Shanghai. She had also witnessed the carnage of the Chungking air raids, and like everyone else in China, she remembered the horrifying fate of Nanking when it had fallen to the Japanese three years earlier; drunken troops had slaughtered 200,000 Chinese.

Even as these thoughts raced through Mickey’s mind, the first of what would be the two-act tragedy of the Battle of Hong Kong was unfolding in the hills above Kowloon. British commanders, anticipating an attack from a Japanese naval task force that was lurking just south of Hong Kong Island, had redeployed their forces. Maltby and his staff remained confident that the troops stationed on the Gindrinkers’ Line could repel any enemy attack. The Japanese feint worked perfectly. As their planes were attacking Kai Tak Airport, hundreds of their soldiers from the 38th Infantry Regiment crossed the border separating the New Territory from occupied China. These advance units of the 60,000-man Japanese 23rd Army traveled quickly on foot and in armored cars. They encountered no resistance during the first four miles of the attack. This puzzled their field commander, Lieutenant General Sano Tadayoshi. He feared a trap, but ordered his troops to press ahead regardless.

What Tadayoshi soon grasped was that for all the talk of British military prowess, Hong Kong’s defenders were ill prepared, poorly armed, and led by officers out of touch with reality. The strength and speed of the Japanese offensive caught the British off guard. Forward elements of the 38th Infantry Regiment had reached the Gindrinkers’ Line early on the afternoon of December 8. Guided by detailed maps drafted by the observant Colonel Suzuki and other spies, the Japanese troops made quick work of the defenders. Japanese commandos infiltrated the British positions that night, killing the sentries who patrolled the vital gaps between the gun positions. The Allied soldiers in those positions then did not stand a chance. Most were still in bed early on the morning of December 9 when they were slaughtered by Japanese grenades, bullets, and bayonets. With them died any hope of stemming the enemy advance.

Japanese commanders knew this and were now hell-bent on quick victory. Thousands of battle-hardened troops poured through a widening gap in the British lines. The Japanese chased the defenders down the Kowloon Peninsula and onto Hong Kong Island in just five days—four ahead of the schedule drawn up by military planners in Tokyo. By Friday, December 12, the Japanese army, aided by Chinese fifth-columnist saboteurs in Hong Kong, had overrun Kowloon. Lieutenant General Sakai was poised to begin part two of his battle plan: the siege of Hong Kong Island.

It began early on the morning of Saturday, December 13, when Japanese artillery in Kowloon began a murderous barrage on Victoria. Shells rained down on Victoria Peak and on the town below. At 9:45 A.M. there was an unexpected lull in the firing. A launch bearing a Japanese delegation sped across Hong Kong harbor from Kowloon toward Victoria pier. On board were three high-ranking Japanese officers, a civilian interpreter, two female civilian hostages, and a couple of dachshunds that belonged to one of the hostages. Flying from the boat’s stern was a large white flag. Across the bow was a white banner with the words “Peace Mission.”

Colonel Tokuchi Tada, the head of the Japanese delegation, stepped ashore and was met by startled British officers. The men saluted smartly as a heavy-set Japanese officer with a portfolio in hand announced in English, “Here is a peace offer from our government. Please send it to your Governor-General, Sir Mark Young.” That letter demanded that the colony surrender by 4 P.M. that day or face all-out attack.

“For a few minutes we stood, silent, looking at one another. We were in the middle of the British garrison, yet here were three Jap officers obviously demanding surrender,” wrote American journalist Gwen Dew, an acquaintance of Mickey’s who was the correspondent for the Detroit News. “They were all smaller than I, and I’m five-five. A cordon was flung around the block; and behind British soldiers with fixed bayonets, curious onlookers surged. Someone tried to break through. There were shots.”15

Presently, a staff car bearing a British flag drove onto the pier. Charles jumped out and saluted the Japanese officers, whom he recognized. They then exchanged some papers and spoke quietly for a few moments in Japanese. With that, Charles bowed, got back into the staff car, and sped off toward Government House. After he had gone, Tada approached Gwen Dew, who was busy snapping photos. Tada asked if Dew would like to take a picture of the Japanese delegation. She did. Afterward, Tada chatted obligingly and volunteered information for a photo caption. “The names were important [to the Japanese officers],” Dew realized, “for they were making history.”16

As the crowd on the pier awaited Charles’s return, the Japanese released one of the female hostages, a pregnant Russian woman. The other, the wife of a British civil servant, reluctantly returned to the launch with one of her captors after leaving her pet dogs with one of the steel-helmeted sentries on the pier. After fifteen minutes, Charles returned from his meeting with the governor. Young’s response to the Japanese ultimatum was one word: “No.” An official communiqué later announced that Sir Mark had rejected the terms of a proposed surrender. “It can now be revealed that the Japanese who came from Kowloon under cover of a white flag brought a letter inquiring if His Excellency the Governor was willing to negotiate for surrender,” the communiqué said. “His Excellency summarily rejected the proposal. This Colony is not only strong enough to resist all attempts at invasion, but all the resources of the British Empire, of the United States of America, and the Republic of China are behind us, and those who have sought peace can rest assured that there will never be any surrender to the Japanese.”17 The Japanese bombardment of Hong Kong resumed with renewed vigor at 4 P.M., as threatened.

Initially, only a handful of Hong Kong residents had grasped how grave the colony’s situation was at the onset of the Japanese attack on December 8; an air of unreality continued to prevail. Even after the enemy had seized Kowloon, cut off most of the colony’s water supplies and begun shelling Victoria, some British commanders continued to insist that the Japanese would not try to invade the island. Some people—civilian and military alike—believed it was only a matter of time before planes and ships from Singapore arrived to chase away the impertinent Japanese. British radio reports told of units of the Chinese army that were supposedly attacking the Japanese from the rear, and there were heartening messages of encouragement and support from the King and military leaders in London.

However, there were also alarming reports that Allied forces elsewhere in Southeast Asia had suffered crushing defeats. On December 10, Japanese torpedo bombers had attacked and sunk the British battleship Prince of Wales and her sister ship, Repulse, off Singapore, and a Japanese invasion force was sweeping across the Philippines. From Shanghai came word that Japanese troops had seized all of the city; Mickey hoped that Sinmay and her other friends there had fled. If not, they were now in prison or dead. The Allies were on the run all across the South Pacific. The presence of Japanese officers on Victoria pier demanding Hong Kong’s surrender brought this reality home with startling clarity. It also dashed any hopes that rescuers would arrive from Singapore.

Sir Mark’s terse rejection of the surrender terms enraged Sakai, the Japanese commander. He responded by ordering an all-out two-day blitz. This move was intended to break British morale and soften up the island’s defenses for a planned invasion. Unlike Chungking, there were no air-raid shelters in Hong Kong where civilians could seek refuge. Not that it mattered. Artillery shells were far more terrifying and lethal than aerial bombs. “Once a bomb has popped, it has popped, and the plane can’t stay in one place pegging away at you,” Mickey wrote. “Shells are different. Shells keep coming and hitting the same spot. Shells are the devil.”18

The next few days were a blur of confusion, fear, and carnage. When she was not tending to Carola, Mickey worked in the War Memorial Hospital helping with an inventory of supplies. That did not take long, because in peacetime the hospital had been a private nursing home, and it was not well equipped. The task of organizing what was there was a welcome diversion for Mickey, who did not see Charles again until Wednesday. When she did, he was downcast. Charles took no satisfaction from seeing that his prediction was about to come true: British rule in the Far East was at an end; Hong Kong was indefensible, and the locals could not be counted on to rally to the British cause.

Charles was determined to do his duty come what may, and he urged Mickey to do likewise. She did, but fear became an enemy that gnawed at the heart and the brain. Hilda Selwyn-Clarke also fell victim, weeping uncontrollably at times. She sobbed about how the children—her own six-year-old daughter Mary, Mickey’s baby Carola, and all the other children in Hong Kong—were going to die. Hilda was under enormous strain and guilt, particularly after her husband had ordered nurses at the auxiliary nursing stations on the mainland to remain at their posts even as Japanese troops swarmed over Kowloon. The Selwyn-Clarkes’ house was besieged by relatives of these nurses, many demanding to know why the women had been abandoned to their fate, which in some cases had been gang rape and death. “Strictly speaking, I suppose Selwyn was right; I suppose there isn’t a question of it,” Mickey later wrote. “Nurses must be left to care for the wounded, and in the old days when war was more civilized, the days in which Selwyn was mentally living, doctors and nurses were treated with respect by the enemy. Maybe. I have my doubts.”19

Mickey’s own fears were eased by Ah King, who arrived to supervise the Selwyn-Clarke household when all the other servants fled to escape the shelling and bombing. Mickey joined Hilda and others in the house when they took refuge in the basement. They emerged briefly on Sunday afternoon, when Charles, Alf Bennett, and Max Oxford came calling. The trio were dressed in combat gear. Everyone gathered in the Selwyn-Clarkes’ drawing room, where Ah King calmly served drinks. It was an eerie, almost surreal, scene.

Inside the house, this small group sipped cocktails and chatted as they had done countless times under happier circumstances; it was all terribly dignified and civil. Outside, there was a constant rumble from the enemy shells raining down on the Peak and the sporadic return fire from the British artillery. As they sat sipping drinks, Mickey and Charles held hands. Charles noticed that she was shaking. “I’m worried about you,” Mickey whispered.

He would be all right, he assured her. Charles explained that he and his fellow intelligence officers spent their days in the underground bunker that served as Hong Kong’s military headquarters and communications center. If anything did “happen to him,” he assured Mickey, she and Carola would be looked after. Charles confided he had sent his will to Mickey’s brother-in-law Mitchell Dawson in Chicago. After his divorce, any money left in Charles’s bank accounts in England, as well as the title to Conygar, the family estate in Dorset that he had inherited from his maternal aunt, would go to Mickey and Carola.

The discussion of these arrangements was cut short by a volley of incoming shells that shook the windows. As the group raced outside to see what was happening, Charles advised Mickey and Hilda that the women and children should move somewhere safer. He suggested Repulse Bay on the far side of the island. With that, Charles, Alf, and Max marched off to rejoin the battle. Mickey and her companions wiped away tears as they watched the men go. Mickey knew it was impossible for her, Carola, and the others to act on Charles’s advice. There was nowhere safe now, and it was too late to leave town. They were trapped.

The final act of the Battle of Hong Kong began on Thursday, December 18. That night, after several failed attempts, Japanese troops landed on the east end of the island. Under cover of darkness, foul weather, and a heavy pall of black smoke from burning oil tanks at North Point, they evaded British flares and searchlights to slip across Lyemun Pass. Just a year earlier, a writer for National Geographic magazine had described the formidable British defenses at this strategic 500-yard-wide narrows this way: “Enough barbed wire to fence in all the cattle in Texas stretches and tangles about hilltop searchlight posts, powder magazines, gun emplacements, and across valley trails up which enemy landing parties might try to march.”20 Even this was not enough to hold back the determined enemy. Despite horrendous casualties, the Japanese troops stormed ashore, gaining a beachhead. When they did, wave after wave of reinforcements poured ashore, screaming Banzai-ai! as they threw themselves at the outnumbered defenders. The Japanese roped together and bayoneted twenty captured Hong Kong volunteer soldiers, whose bodies were then pitched down the slopes and into the harbor. Miraculously, two of the men survived to give evidence against the killers before the postwar Hong Kong War Crimes Court.

From high up on the Peak, Mickey watched the battle on the morning of Friday, December 19. In the distance, she saw and heard the fighting as the Japanese troops bypassed Victoria and fought their way inland. Japanese commanders had two objectives: split the island’s defenses and seize the town’s water reservoirs in the surrounding hills. They realized that without drinking water Hong Kong would be forced to surrender quickly. The British, Canadian, and Indian defenders knew this too, and they resisted with grim desperation.

As fighting spread across the thirty-two square miles of island, rumors of Japanese atrocities fueled a growing panic among Hong Kong’s civilian population as the inevitability of defeat became clear. Victoria’s transportation system crumbled. The power was cut, and the town slid into anarchy. Chinese thugs and pro-Japanese gangs roamed the streets and looted shops and homes. Fearing the worst, Selwyn-Clarke sent word that his wife and the others staying in his house should seek refuge in War Memorial Hospital. There was nowhere else to run.

Mickey was working at the hospital when she saw some of the people who had been staying at the Selwyn-Clarke house trudging toward her along a hallway. They were lugging belongings. Then Mickey spotted Ah Cheung with Carola in her arms. A coolie accompanying them carried Mickey’s suitcases. “The Japs were coming!” one of the British men informed Mickey. Terror and resignation were evident in his hushed voice. The words stunned her. Mickey was only vaguely aware of staggering into the dispensary, where she collapsed on a chair and began sobbing. For the first time, she realized that they might all die at the hands of the Japanese—her baby, the Selwyn-Clarkes. Everyone. And she had no idea what had become of Charles. It had been two days since Mickey had heard from him. Perhaps he was already dead. Charles had always been careful never to discuss his work with her, but Mickey had deduced that he was involved in intelligence work. If he was taken prisoner by the Japanese, Charles faced “a rough go of it.” Mickey knew how ruthlessly efficient the Japanese were in extracting information from prisoners.

“I wasn’t fated to stay long in the War Memorial Hospital, but my impressions of that short interval are vivid,” Mickey wrote.21 The nurses who ran the facility with an iron hand were determined to maintain order. Even when the enemy shelling intensified, they resented the tearful, hungry, dirty, and tired refugees who came knocking on the hospital door. Most were turned away, and Mickey knew if she had not been part of the Selwyn-Clarkes’ extended “family,” she, too, would have been told to leave. With shells falling all around and looters and fifth-columnist saboteurs in the streets, she had nowhere else to go.

Mickey and Carola slept on the floor of a hospital room they shared with the Selwyn-Clarkes and several other people. Finding enough to eat was a major concern. When the hospital’s Chinese kitchen staff fled, Ah King stepped into the breach and began cooking. However, his job became impossible when the members of Hong Kong’s Food Control Committee moved into the hospital and assumed responsibility for rationing the limited supplies in the pantry. Mickey noticed that committee members always ate before everyone else. They dined on potted meat and bread, while the others made do with meager servings of rice or cereal.

Mickey cared less about herself than about finding enough food to keep Carola alive. She continued to be haunted by recurring nightmares about her baby starving to death. As Carola’s appetite grew and she refused to breastfeed, she cried for more substantial solid food. Even so, Mickey’s worries about food and personal safety vanished in a split second on the morning of Saturday, December 20, when Hilda breathlessly reported some news she had just heard from her husband: Charles had been badly wounded on Friday in the Battle of Shouson Hill, on the south side of the island near Repulse Bay. A Japanese bullet had caught Charles high on the left side of his chest. He had lain in a paddy field overnight. The medics who found him had carried him to Queen Mary Hospital in Victoria, where Selwyn-Clarke was on duty. It was he who had sent word that Charles’s doctors thought he might survive his wounds.

“I am inclined to gloss over it and say I felt nothing but a very strong impulse to go to Charles,” Mickey wrote, “but that wouldn’t be true. I remember feeling like a volcano, and then I was mixed up in a ridiculous quarrel, after all those days of self-control, with Hilda. She didn’t think I should go to the Queen Mary. She was willing to fight like a lioness to keep me with her.”22

Mickey refused to listen. After making arrangements to have her friend Vera Armstrong come to fetch Carola and Ah Cheung (Vera had taken refuge in the basement of a friend’s house not far from the hospital), Mickey donned a tin helmet and set off down the Peak on foot, accompanied by a young man who was on his way to Happy Valley. He agreed to escort her to the downtown business district. From there she hoped to hitch a ride to Queen Mary Hospital, in the town’s west end. That was good enough for Mickey. She had resolved to go to Charles or die trying.