The Teia Maru, the ship that carried Mickey and Carola on the first leg of their 18,000-mile voyage home, steamed west out of Stanley Harbor next morning, September 23, 1943. The Japanese-controlled English daily the Hongkong News (sic) reported that before the vessel left, the 1,400 Canadian and American repatriates on board had “expressed their gratitude to the authorities for the kind treatment and consideration which had been accorded them.”1 The article neglected to mention that Japanese authorities had warned these same people that denouncing the living conditions in Hong Kong’s internment camps would affect the treatment of those left behind and might jeopardize any further prisoner exchanges.

If Mickey expressed “gratitude” for anything, it was that her voyage home had finally begun; there could be no turning back for her or anyone else aboard. Their ship was bound for Mormugão, a neutral Portuguese port on India’s west coast, south of Bombay. Here they would await rendezvous with a Swedish relief ship, the Gripsholm, loaded with Japanese nationals traveling in the opposite direction. Under the circumstances, the repatriation of such a large number of people was an ambitious undertaking.

“The whole of Asia was either at war or not in a position to handle such an exchange,” American journalist Max Hill wrote of a 1942 prisoner swap, of which this one a year later in many ways was a carbon copy. Only the port was different; on that occasion “the Gripsholm had to sail from New York, cross the Atlantic, swing around the southern tip of Africa and bring the Japanese safely into port at Lourenço in Portuguese East Africa. [The] American men, women, and children who were leaving the Japanese Empire, Shanghai, Hong Kong, and Saigon … had to skirt the coast of Asia, pass through the Sundra Strait in the Netherlands East Indies, cross the Indian Ocean—keeping far out from the shore to avoid war zones—and then tie up in the same port.”2

Despite their exhaustion, the first day at sea was a restless one for Mickey and her infant daughter. Like most toddlers, Carola crawled for miles in her sleep. Sharing a bunk with her at night was akin to sleeping with a bag of puppies; Mickey drifted in and out of consciousness. When finally she did nod off, her mind was filled with terrible dreams—the face of a starving Charles, torpedoed ships, Carola sobbing, sharks slicing through the roiling ocean waves.… It was nearly too much to take.

Despite the presence of red ants and human clutter, both of which were everywhere on the ship, Mickey tried to sleep on a straw mat that she spread out on her cabin floor. The arrangement proved unworkable, and most nights while Carola settled Mickey went up on deck. There she talked with other passengers or paced endlessly around the ship, which was “lit up like a birthday cake” to make it easy for submarines from both sides to identify.

It was on these nocturnal rambles that Mickey discovered the social structure that had already formed. Most of the Teia Maru’s passengers were what Mickey termed “ordinary burghers”: diplomats, journalists, oilmen, and businesspeople. However, there were a couple of other groups as well. One was a large contingent of nuns and missionaries, who had been trapped at their charges when the war broke out. Then there were about a dozen rough-and-tumble characters whom Mickey dubbed “the Dead End Kids.” Some were merchant seamen, some professional gamblers. Others were soldiers who had somehow escaped from the military. The Dead End Kids were ensconced in a couple of cabins in the second-class passenger area. There they played cards, drank, swore, fought, and generally raised hell, although they were friendly toward Mickey. They were amused that she smoked cigars, and one of them took a liking to Carola. Relations between the Dead End Kids and the other passengers were less cordial. “I still can’t decide who behaved with less kindness and tolerance—the Dead End Kids or the missionaries. Their attitude towards each other was the same, a fierce hatred,” Mickey observed.3

In an effort to keep the peace, the ship’s passenger organizing committee formed a vigilante group. At first, the Dead Enders ignored—and resented—this “Goon Squad,” as they dubbed them. When the Dead Enders ran out of money to buy liquor from the ship’s stores, they began stealing from fellow passengers. This was all too much for the organizing committee, who delegated Mickey to deliver an ominous message to the Dead Enders: unless they shaped up, “Washington” had authorized the Goon Squad to use “any means necessary” to restore order. This included literally throwing offenders off the ship. In the face of such a threat, things quickly quieted down. The rest of the voyage was uneventful, apart from an uproar on the last night at sea, when the Dead Enders joined other passengers in looting a supply of sake that the ship’s Japanese crew had stashed away for their own repatriates to drink on the return voyage. The raid was carried out with such precision that by the time the crew organized a search of the passenger cabins, it was too late to recover any of the missing bottles or even to seek retribution. The next morning the Teia Maru arrived at Mormugão.

There they rendezvoused with the Gripsholm, which arrived the next day carrying hundreds of jubilant Japanese nationals who were bound for home. It was an extraordinary scene. The hull of the Gripsholm had been painted in the blue and yellow of the Swedish flag and with gigantic white letters that read: “Diplomat. Gripsholm Sverige.” As the ship docked, repatriates crowded to the railings of both vessels. Mickey saw how well fed, well dressed, and content the Japanese aboard the Gripsholm were. They burst into song as their ship drew near the quay. By comparison, the scene aboard the Teia Maru was funereal; people stood in numb silence. “We were refugees from Japan and Japanese-occupied territory,” Mickey wrote, “skinny Americans, shabby Americans, brown-paper parcel Americans, in a particularly chastened frame of mind. We were dried out and grimy, on a filthy little ship.”4

Mickey, Carola, and their fellow passengers waited two more long days to escape the Teia Maru. When finally it was time for the exchange, the passengers lugged their belongings down the gangplank, onto the dock, and then onto the other ship. The entire process took only a few minutes. Once it was complete, there was a deafening silence among the passengers aboard the Teia Maru; this time it was the Japanese who looked on in stunned silence as the Americans on the Gripsholm sang and laughed.

Conditions were heavenly on the ship that was to take Mickey and Carola home. There were no more pesky red ants. The cabins were clean and comfortable. The crew was friendly, the food was good—and there was lots of it. Mickey was delighted to discover there was even a hairdresser aboard. The passengers “wallowed in Swedish luxury.” Carola, malnourished and underweight, had never seen such plenty. The New York Times would later report how “many of [the passengers] had put on from eight to twenty-five pounds during their voyage on the Gripsholm.”5 Mickey used some of her precious dollars to hire an amah for Carola. Kitty Bush was a young Eurasian woman who spoke Cantonese, the dialect Carola had learned.

There was, as Mickey noted, “room at last for our egos to spread out.”6 The passengers began reverting to familiar behavior patterns. The diplomats became aloof. The missionaries preached. And the businessmen began issuing orders to anyone who would listen, while their wives set about organizing social life aboard the ship. Even the Dead End Kids fell into step; as they had aboard the Teia Maru, they holed up in a couple of cabins where they again proceeded to enjoy themselves, this time much more quietly.

The Gripsholm arrived at Port Elizabeth, South Africa, a week later. From there it was eleven days sailing to cross the Atlantic to the Brazilian city of Rio de Janeiro. At sea on October 17, Carola celebrated her second birthday. Otherwise, it was a quiet voyage. “Nothing ever dragged as much as the two weeks it took to get us from Rio to New York,” Mickey wrote. “It wasn’t just my own idea; everybody noticed it. Moreover, everybody was feeling the way I was about reaching New York, too. Instead of being impatient and eager to get there, I was afraid. I was appalled at the prospect of diving into life again. I saw freedom ahead of me, days full of my own decisions, a continent to wander in without exit or entry permits and without permits to take my baggage, permits to own my baby. I was scared to death.”7

The Gripsholm steamed into New York Harbor the night of November 30, 1943, with all lights blazing. As the big ship glided past the Statue of Liberty on Bedloe’s Island, many repatriates braved the cold to gather on the after-promenade deck, where they broke into a loud chorus of “God Bless America.” The sound of their joyful voices rang out in the darkness that cloaked the calm waters of the Upper Bay.

It was too late to disembark, so the ship’s captain dropped anchor, and everyone spent one more sleepless night aboard. There was a festive atmosphere. The next morning, shortly before 10 A.M., the Gripsholm completed its long voyage when tugs guided it to Pier F in Jersey City, just across the river from Manhattan. A noisy throng of cheering friends, families, and journalists awaited the passengers who crowded to the railing or peered out the ship’s portholes into a thick morning fog. Newsreel cameras recorded the joyful scene as the repatriates called out to loved ones. Some among the waiting crowd waved little American flags or threw confetti and streamers as the ship docked. Others wept tears of joy. When Red Cross officials boarded the Gripsholm, they did so carrying sacks overflowing with 20,000 welcome home letters and messages, as well as new clothes for everyone who needed them. The emotional homecoming was front-page news in the next morning’s edition of the New York Times.

It was two hours before the first passengers came down the Gripsholm’s gangplank and into the welcoming arms of loved ones. The delay was due to customs officials who filled out myriad forms and scanned the passengers’ documents. When that was done, agents from army and navy intelligence, as well as the Federal Bureau of Investigation, went to work; they were searching for enemy spies and collaborators. Everyone aboard the ship was interviewed. The process took so long that two hundred passengers, Mickey and Carola among them, were forced to spend yet another night aboard the ship. Thirty of the repatriates, even less fortunate, were taken away to Ellis Island for more extensive questioning.

Mickey also received special attention. American intelligence officials knew little of her life in China. Having lived abroad since 1935, she was a relative unknown to the FBI. Her file initially consisted of no more than a few sheets of paper with the barest of biographical information, most of it incorrect or out of date. All that changed the day that she arrived home. According to declassified government documents, FBI agents sought out at least two “confidential informants” in New York City who provided information about Mickey and her life in China. Thus, although most of the Gripsholm’s passengers were asked a few perfunctory questions while their papers were being processed, Mickey was interrogated at length. She was given a quick physical examination—“height: 5’4½”, weight: 130 lb, hair: dark brown, eyes: hazel,” the report noted—and then interviewed by a succession of eight panels of military intelligence officers and FBI agents. The men asked her the same questions over and over, hoping to catch her out. The ordeal lasted all day, although everything became a blur to Mickey after only a few hours. “It was all very confusing,” she recalled, “and so very tiring.”8

At one point, Carola began to cry uncontrollably. This so unnerved Mickey’s questioners that they suggested that she and a female customs officer deliver the child to “a relative” who was waiting on the dock. “As I stepped down from the gangplank, a whole lot of lights flared in our faces,” Mickey wrote. “Carola screamed, of course, and started hitting out at the world, most of the blows landing on me.” A crowd of reporters surged forward, pencils and notebooks poised. “What’s your name? Who are you?” they shouted. Mickey stood before them dumbfounded, vainly trying to comfort her daughter. Suddenly a woman emerged from the crowd. “I stared at her utterly strange, emotion-suffused face, and then, just before she put her arms around me, she turned into my sister Helen,” Mickey wrote. “I almost laughed because I hadn’t known her at once, but there was no time to tell her about it.”9 There was also no time to talk; the customs officer tapped Mickey on the arm and reminded her she was obliged to return to the ship.

Later, when she tried to recall other details of the day and of her interrogation, Mickey could not. It had all become an endless swirl of names, faces, and questions. The men asked her about every detail of her life in Hong Kong, her relationships with Sinmay and Charles, and her dealings with Japanese officials such as Takio Oda, Tsuneo Hattori, Chick Nakazawa, Colonel Noma, and General Suginami.

Why hadn’t she been interned like other Americans?

Why had she received “favors” from the Japanese?

Why had she fraternized with such high-ranking enemy officials?

Had she been a Japanese spy?

On and on it went. Mickey answered each question truthfully, holding nothing back. She even revealed that she had carried home with her a cryptic note from a Japanese friend in Hong Kong to some people in New York. It read: “Japanese affection for/Japanese verse is the/glowing disk of the rising sun/over Japan’s mountains.” The message had been typed on a tiny piece of cloth that Mickey had sewn into the sleeve of Carola’s blue silk dress. This revelation piqued the curiosity of the FBI agents, who were convinced they were on to something big. The dress was dispatched to the agency’s headquarters in Washington, where the fabric was examined in the labs and the message was studied by cryptographers.

In the end, the FBI found nothing incriminating. Although they remained suspicious, Mickey was finally permitted to leave the ship late on the afternoon of December 2, 1943. By the time she stumbled down the ship’s gangplank, most of the crowd on the pier had gone home. The only one waiting for Mickey was a friend of her brother-in-law, who drove Mickey to Helen and Herbert’s downtown apartment. There she found the group of friends and relatives eager to welcome her gathered in the living room. They had a problem. Carola, howling loudly, had scrambled under the sofa and stayed there for several hours. She spoke no English, of course, and did not know her aunt or anyone else who tried to lure her out. Carola was inconsolable. Mickey extracted her daughter, dried her tears, and hugged her. Then she looked around the room at the crowd of smiling faces. There next to Helen and Herbert was Mickey’s mother Hannah, who was now a spry eighty-seven-year-old. She had come all the way from Chicago to welcome Mickey home. “Well!” was all Hannah could think to say. “Well!” Now it was her turn to hug and Mickey’s to cry. Afterward, they sat down to talk. “How’s everybody, and where are they?” Mickey asked. There were two years of family news to catch up on.

Mickey had last seen her sister Helen on that day in June 1935 when she had sailed from Shanghai, leaving her sister behind in China. It had been even longer since Mickey had seen her mother. Hannah was in New York for her daughter’s homecoming because New Yorker editor Harold Ross had paid her train fare from Chicago and put her up in a downtown hotel. Mickey never forgot Ross’s kindness, which was typical of him.

On the evening of December 2, Ross and his wife Ariane (his third) visited Hannah’s hotel room, where Mickey and Carola were spending the night. Ross and Mickey had a long conversation, for he was full of questions about China, a country that fascinated him. For all his presumed worldliness and sophistication, Harold Ross had traveled very little. He had been abroad just once, while serving in the U.S. Army during the First World War.

In the days that followed, John Gunther, Donald Hanson and his wife Muriel, and many other friends and acquaintances dropped by to say hello. Mickey’s return to New York was well publicized in the media, although not all the coverage was positive. Publisher Bennett Cerf reported in the gossip column that he wrote for the Saturday Review of Literature how “the publicity-wise Emily Hahn” had returned from Hong Kong with her “two-year-old half-Chinese baby” in her arms and “a long black stogie” in her mouth. Cerf added, “There were a lot of other people on the Gripsholm … who had a darned sight more interesting and perilous time than the photogenic Emily, but who were more or less overlooked in the Hahnward rush.”10

Mickey, who was fast recovering her feistiness despite her recent travails, responded to the column with a snarly letter to the editor. She chided Cerf, whom she suggested should stick to publishing, while the Saturday Review should stick to “reviewing.” She also complained that Cerf’s account of her homecoming “seems to have been thought up by Mr. Cerf himself, perhaps at a nightclub. There were no reporters allowed aboard the Gripsholm and I wasn’t interviewed at all, by anyone but government officials.”11

Mickey’s friend Katharine White, one of her New Yorker editors, insisted on taking Mickey to consult with “one of The New Yorker’s finest attorneys.” When she did, the attorney sent Cerf a “threatening letter.” He apologized in his next column, conceding he had been wrong about Carola being half Chinese. “He also pointed out that her father was, in fact, a married British army officer who was now a POW in Hong Kong,” Mickey recalled with a laugh. “I told Katharine we should have left well enough alone.”12

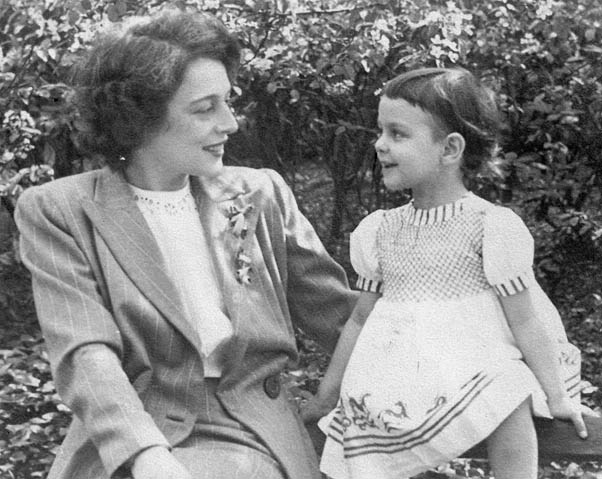

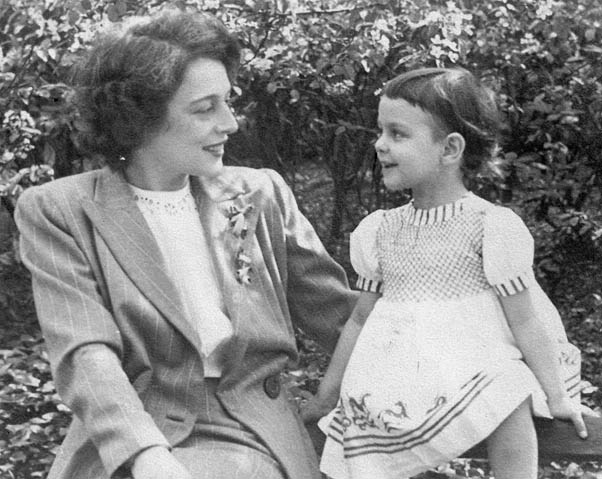

Mickey and her daughter Carola in Central Park in 1944. The park was one of Mickey’s favorite places in New York City. Courtesy Emily Hahn Estate.

Mickey could afford to laugh off the incident. She had other things to worry about as she struggled to rebuild her life. Fortunately, money was not a problem. Carl Brandt had deposited thousands of dollars in royalties from The Soong Sisters and Mr. Pan books in Mickey’s bank account, which Helen had tended to in her sister’s absence. Mickey used the money to rent a suite in a downtown hotel and to buy a new typewriter. She was bursting with creative energy. Over the next few weeks, Mickey wrote dozens of short stories and magazine articles about her wartime experiences in Hong Kong. One of the first was a two-part “Reporter at Large” series for The New Yorker, which told the true story of her experiences aboard the Teia Maru and Gripsholm. The articles attracted a wide readership because they were among the most compelling accounts of the wartime repatriation of American civilians from Japanese-occupied territories. Other writers have told of similar experiences, but no one has ever written as eloquently or in as much detail as Mickey did. She also began work on a book, a startlingly candid memoir of her eight years in China. Mickey had a phenomenal memory, and she used it to full advantage now. She was determined to hold nothing back, to tell her story as fully and truthfully as she possibly could.

The emotional price she paid for doing so was high. The writing brought back a flood of vivid memories—happy as well as painful—of her life in the Far East. Most acute were her feelings for Charles. Mickey had heard nothing more of him since leaving Hong Kong. Although she remained hopeful, in her heart she despaired of ever seeing him alive again. The thought of Charles dying alone in a dark, filthy prison cell from starvation or torture filled her with longing and smoldering rage. Mickey was angry at the fates who had toyed with her so cruelly, angry with the Japanese and the British for their stupidities, and angry at the war. But most of all, she was angry at herself for being weak and for having left Hong Kong. It mattered little that she knew that she had done what was best for everyone; in her heart Mickey still felt she should have stayed for Charles’s sake. Had she done so, Mickey and Carola almost certainly would have perished.

The situation in Hong Kong had continued to deteriorate in the wake of the Teia Maru’s departure. As it did, Charles became swept up in deadly prison camp intrigues. The Japanese guards were determined to control the flow of goods and information into and out of the POW camps. The punishments were harsh for those who were caught smuggling messages or listening to BBC war news on makeshift radio receivers. Nevertheless, the prisoners had developed an elaborate underground network that was fueled as much by ingenuity and courage as by sheer boredom and the corruption of many of the Japanese guards and their Chinese and Indian collaborators.

In late September 1943, some of the men in the British POW camps figured out that the supply truck that served them also made runs out to Stanley Camp, the civilian internment facility. Someone devised a way to hide messages inside one of the truck’s hubcaps, which was cleverly modified for the purpose. “That was fine,” explained Charles’s friend Alf Bennett, “but what happened was that those bloody people, instead of using this for good and useful information, began using it to send personal messages to wives, girlfriends, and others at Stanley Camp. Of course, the Japanese found out about this stupid chit chat.”13

An Indian informer passed on the information to the Japanese. Although he had not been involved directly, Charles was implicated and was “arrested” by the Kempetai, along with several other British officers. All were found guilty at a court-martial. The New York Times and many other American newspapers subsequently carried a wire news service story from the Associated Press that claimed Charles was one of two British officers who had been executed for being caught with a radio receiver.14 This chilling news fulfilled all of Mickey’s darkest fears. When she scrambled to learn more, her frantic phone calls yielded no further information. Mickey spent several tearful and sleepless nights being consoled by family and friends. In her heart, she would not, could not, believe that Charles was dead. When approached for a comment by a Times reporter, Mickey put on a brave face. “Unless there is more evidence, I do not intend to believe the rumor,” she said.15 Still, she had only blind faith to sustain her.

Mickey did what she could to get on with her life. She rented an apartment on East 95th Street in Manhattan and found a nursery school for Carola. The principal suggested that Mickey have Carola examined by a doctor who was doing some innovative work with young patients. Dr. Benjamin Spock, a native of nearby New Haven, Connecticut, was the first American physician to complete professional training both as a pediatrician and as a psychiatrist. When Mickey and Carola met him, child-care guru-to-be Spock was still developing the ideas he would present to the world in Baby and Child Care (1946).

Spock said Carola’s lack of hair and her tiny size were related to the nutritional deficiencies she had suffered. Both would correct themselves as her diet improved, he predicted. Her dental problems could be solved by a dentist. As for her fearfulness, Spock prescribed megadoses of maternal affection. “Spoil her. Within reason,” he instructed Mickey.

She was more than willing to comply. Here was an opportunity to make up for all the deprivations and hardships Carola had endured in Hong Kong; Mickey might never see Charles again, but she would love their child with all her heart and soul. To the dismay of many of her family and friends, Mickey smothered Carola with affection. She bought her toys and anything else that she wanted. Nothing was too big or expensive. Mickey moved Carola’s crib into her bedroom and installed a night-light. She doted on her tiny daughter. The results were wondrous. Just as Dr. Spock had predicted, Carola responded. Soon she was looking and behaving like a normal American three-year-old.

Mickey’s own transition to her new life in New York was considerably more arduous. She found that time stretched ahead endlessly with no real rhyme or reason. The uncertainty over Charles’s fate left Mickey empty and utterly alone. Nothing else seemed important; she was slipping into a depression. In early December, Mickey, Carola, and Kitty, the new amah, left on an extended Yuletide visit to Chicago. Rose and Mitchell Dawson had offered Mickey the use of a study in their seventeen-room house in suburban Winnetka, where she could work on a planned book about her China experiences. Hannah was also staying with the Dawsons, and Mickey’s younger sister Dauphine, who had married and was also living in Winnetka. Sadly, what initially promised to be both a carefree family reunion and a productive work time soon became an unpleasant ordeal for everyone. Rose, who had stepped into Hannah’s shoes as the Hahn matriarch, was every bit as adamant as her mother had been in her opinions about family etiquette. This put her on a collision course with Mickey.

Rose and Mitchell Dawson had three children: a son named Greg and two daughters, Hilary and Jill. Mickey’s arrival in the house made vivid impressions on all of them. For as long as any of the children could remember, their aunt Mickey had been someone who sent letters and occasionally a photo from distant China. All that the children knew about her had come from listening to their parents talk. Now suddenly here was Aunt Mickey in the flesh; it was not easy to reconcile expectations with reality. Mickey recalled how disappointed nine-year-old Greg was to discover that she was not a monkey. He had somehow gained that impression. Hilary remembered how her mother was “angered, shocked, and astounded” by Mickey’s attitudes and behavior.16 When they got to know her, the Dawson children decided their aunt was so carefree and exotic she must have dropped in from another planet; Mickey demanded nothing of her nieces and nephew and imposed no restrictions on them.

Greg remembered his aunt Mickey’s “un-Dawsonlike” attitude toward money. “[She] had been deprived of money for so long that when she returned home to the U.S. she went crazy spending the money which had accumulated in her bank account while she was away. Mickey was Lady Bountiful. It was as though she said, ‘Let’s spoil Carola, and we’ll do Greg too while we’re at it!’”17

Mickey bought the children a pet monkey. For Christmas, she gave Greg an elaborate Chinese warrior costume that he coveted; Rose was shocked at the extravagance. She was no less astounded when she learned that Mickey had bought her son an expensive miniature pipe. Rose, Mickey, and Greg were shopping in Chicago one day when Mickey stopped at a tobacco shop for cigars. There, in a display case, Greg spotted a exquisite Kaywoodie miniature pipe. He had to have it. Rose thought the $10 price ridiculous, and she said so. Mickey was of a different mind; she promptly bought the tiny wooden pipe, which she secretly gave to Greg.

Such gestures heightened tensions between Mickey and Rose, and it was not long before things came to a head. Surprisingly, the trouble began not because of Mickey’s relationships with the Dawson children, but rather over her treatment of Carola. A reporter from the Chicago Sun came by the Dawson house one evening in late December to interview Mickey, who talked freely about her relationship with Sinmay and about the circumstances of Carola’s birth. Mickey also allowed a photographer to take a shot of Carola in her crib. Mitchell, who observed all of this, listened in on an extension when the reporter phoned in his story, the details of which sent Rose into a rage. Mitchell called an editor friend at the newspaper to ask that the article be killed. It was not. The impact was immediate when it appeared in the Sun under a headline proclaiming, “I was the concubine of a Chinese!” The Dawson children were delighted to see their cousin Carola’s picture in the newspaper; Rose was furious that Mickey had “exploited” her daughter for what Rose regarded as selfish reasons. Mickey took exception, of course, and all hell broke loose. When the shouting ended, Mickey packed up Carola and her amah and moved out of the Dawson house and into a hotel.

Back in New York, Mickey began working feverishly on her China memoir, which she finished in just a few months. China to Me was a book so unflinchingly honest and candid that it sent some people reeling. In it, Mickey related the details of her experiences in China from 1935 through to her 1943 repatriation aboard the Gripsholm. It was all there—her “marriage” to Sinmay, her relationship with Sir Victor Sassoon, her opium addiction, and the whole story of her love affair with Charles. She spared none of the details; after all, the book was a “partial autobiography,” as Mickey termed it. But it was more than that. China to Me was also a wondrous blend of reportage and personal memoir written in Mickey’s own inimitable style. Mickey, who insisted she had no political allegiances, nonetheless held strong opinions about what was happening in China, and she was not reluctant to share them. What she had to say put her at odds with a vocal lobby of left-leaning sympathizers who had been working hard to paint the Nationalist forces under Chiang Kai-shek as corrupt and incompetent.

Mickey asserted that the American public had been hoodwinked into believing that the Communist guerillas under Mao Tse-tung comprised the only Chinese military force that was making a stand against the Japanese. While conceding that the efforts of the Communists were “inspiring and invaluable,” Mickey argued that much of their effectiveness was lost because of internal squabbles and petty personal jealousies among the leadership. “I am not trying to run them down, Agnes Smedley and Ed Snow and General [Evans] Carlson and the rest of you; I’m only trying to undo some of the harm you have unwittingly done your friends,” Mickey wrote. “You have worked people into a state where they are going to be awfully mad pretty soon. They are heading for a big disappointment.”18

Mickey went on to chide those American journalists in China who “out of a frustrated sense of guilt, a superior viewpoint of things as they are, and of a tendency to follow the crowd,” had jumped on the bandwagon and were boosting America’s faith in the good intentions of the Chinese Communists. “Most newspapermen don’t know any more about the Communists in China than you do,” she cautioned her readers.19

China to Me sold more than 700,000 copies and caused a sensation when it was published in the fall of 1944. Mickey’s candor landed her smack in the middle of a growing public debate about China, and that alienated many former friends. Agnes Smedley, whom Mickey had befriended in Hong Kong, was especially irate. She had taken exception to Mickey’s book The Soong Sisters, dismissing it as Nationalist propaganda. China to Me was the last straw for Agnes, who regarded it as a personal attack and began denouncing Mickey to anyone who would listen. Mickey attended a backstage reception for panelists who had discussed China on the NBC radio show America’s Town Meeting. Agnes, who had taken part in the program, reported in a letter to a friend that “the bitch Emily Hahn came, and of course we [did] not speak.”20

Reviewer T. A. Bisson of the Nation, a journal that in 1944 strongly supported many leftist causes, led the mob that was counterattacking Mickey. “Her prejudices—the strongest one is against ‘leftists,’ a term she much affects—are almost as fascinating as her naivete,” wrote Bisson. “God rest her soul! Both China and the leftists may, perhaps, manage to outlive even Emily Hahn’s commentary.”21

More typical of the media reception for China to Me were the comments of reviewer H. L. Binsse of Commonweal, the Roman Catholic weekly. Ironically, he ignored Mickey’s amorous adventures, preferring instead to focus his attention on the book’s political aspects. Binsse pointed out that in “nine-tenths of its pages” China to Me was a “vivid and moving account of life on the China Coast.”22 Most other reviewers agreed, even Adrienne Koch of the New York Times Book Review, whose enthusiasm for China to Me was tempered; she acknowledged Mickey’s storytelling gift. “She’s as good as the best over a martini,” wrote Koch. “Nobody will be so dour as to resent her autointoxication.”23

It was not politics as much as Mickey’s morality—or perceived immorality—that disturbed many readers. As had been the case with her controversial 1935 novel Affair, which had dealt with abortion, Mickey’s candor in dealing with sensitive issues upset conservatives. Reviewer Katharine Shorey of Library Journal noted that “[China to Me] will be very valuable for all libraries, but its extreme frankness may unfortunately rule it out of school libraries.”24

Predictably, all of the controversy and the resulting publicity spurred sales of the book. Despite wartime paper shortages, which delayed reprintings, China to Me climbed to second place on the national nonfiction best-seller list. Sales would have been even better—and Mickey’s literary career much different—had the Book-of-the-Month Club (BOMC) not opted to take a new book of humor by Mickey’s New Yorker colleague James Thurber as its selection for the 1944 Christmas season. The Thurber Carnival was a much safer choice for middle America than a topical book about politics and love in wartorn China.

Despite the BOMC disappointment, Mickey suddenly found herself in demand for interviews and appearances. She began working with a Broadway producer on a possible play about her adventures aboard the Gripsholm. America had finally discovered the literary talents of Mickey Hahn; she had become an instant celebrity. In late 1944, she began a series of lucrative public lectures for which she was billed as “a woman years ahead of her time.”

No one was more puzzled by all of this attention than Mickey herself. “The hubbub I have caused surprised even me,” she confided in a letter to her old friend Sir Victor Sassoon, who was living in Bombay, India. “I don’t consider [China to Me] a very shocking book, and I certainly don’t think they are justified in assuming that I rolled in the hay with every man I mentioned. After all, I mention only one affair, and Charles was practically legal. American book reviewers, who are obviously the most frustrated people in the world, seem to think if there was so much smoke, there must have been fire, too.”25

Flush with success, Mickey splurged by renting an eleven-room townhouse on East 95th Street in upper Manhattan. However, despite her newfound affluence, Mickey was deeply troubled. “I am terribly homesick [for China],” she told Sir Victor. “I am working terribly hard—harder than I ever did in my life, but since a good deal of it is only for Carola and me, I feel guilty that I should be doing more about the war.”26

Mickey’s life had taken on an air of fantasy; nothing seemed real, not even the bountiful supplies of food and consumer goods that were available in New York shops. With rationing still in effect, butter and nylons were in short supply, and Mickey began seeking out these items on New York’s version of the black market. It was the “old familiar thrill of outwitting authority,” as she put it, that inspired her to do so.27 What’s more, she boasted to family and friends of her prowess in finding goods others could not. “I’d come home from Hong Kong wearing a chip on my shoulder, and it wasn’t to be jiggled off all that quickly,” Mickey later said. “I couldn’t have explained any of this to my family—I didn’t understand it myself.”28

Those who were close to her were distressed by Mickey’s sometimes outlandish behavior. Her salty language and cigar smoking were the talk of the town, as was her decision to pose in the nude for New York society photographer George Platt Lynes. Helen and other family members were no less disturbed by Mickey’s decision to hire a Dutch-born “artful dodger” named Willy Schumacher as her cook-houseboy. Willy, a friend of the Dead Enders whom Mickey had met aboard the Gripsholm, was looking for work and Mickey needed help, so she hired him. “He was small and rat-like, a really rough character,” recalled one of Mickey’s nephews.29

Given Willy’s background, it was not surprising that he was adept at securing scarce consumer goods on the black market, particularly prime grade steaks. He was also a good cook, so Willy and Mickey got along well. However, his unpolished demeanor was not his worst shortcoming. Far more ominous was that Willy and his wife were addicted to morphine. It was not long before Willy was supplying the drug to Mickey. She embraced its soothing properties, which helped her to forget her pain. Although morphine initially produces euphoria in its users, chronic abuse has serious physiological and emotional side effects, one of which can be depression. Mickey knew this, and she agonized over the dangers of slipping back into drug dependency. Apart from a few pipes of opium she had shared with friends in Hong Kong, she had been “clean” for almost four years.

The emotional and physical strain were taking a terrible toll on Mickey, who continued her headlong rush toward disaster. She never saw what was coming. Four years of poor nutrition, stress, and troubles all caught up with her during a mid-January 1945 visit home, during which she was to give “a hush-hush” lecture to some officers at the military base in Evanston, Illinois. An army doctor there took one look at Mickey and whisked her to a nearby hospital for a shot of penicillin, which he hoped would relieve her burning fever and the howling pain from two nasty carbuncles. The penicillin proved useless against the fever and the boils. What was wrong with Mickey was far more serious than she or anyone else initially realized. Mickey Hahn was in a fight for her very life.