Chapter 1

Camus, son of France in Algeria

All too often Camus’s works (particularly The Stranger) have been considered only as free-standing masterpieces of French literature. However, questions of identity and historical context become more pronounced in the colonial situation. To grasp fully and appreciate Camus’s achievements and the ambiguity of his works, it is important to consider the historical situation that shaped his formative years.

Albert Camus (1913–60) was a French citizen born in Algeria. He would live there from his birth until the middle of the Second World War. His father, Lucien Camus, worked as a foreman in a vineyard in the district of Mondovi, about 100 miles east of Algiers. Lucien married Catherine Hélène Sintès, a homemaker, on 13 November 1910, and three months later, Albert’s older brother—also named Lucien—was born. Albert was born in Mondovi nearly three years later, on 7 November 1913.

The ancestry of Camus’s family is closely tied to France’s presence in Algeria. Records indicate that his paternal great-grandfather, Claude Camus, came to Algeria in 1834, shortly after France’s conquest. His maternal grandfather, Étienne Sintès, was born in Algiers in 1850, though Étienne’s wife, Catherine Marie Cardona, was born in Spain. Camus’s lineage was typical of French citizens born and living in Algeria, who were called pieds-noirs, literally, ‘black feet’. In the early 20th century, pieds-noirs originally referred to the mostly Arab shipmen who worked barefoot in the charcoal bunker in the hull of the ship. During the Algerian War of Independence (1954–62), the term eventually denoted all French citizens born and living in Algeria. (This is how I will refer to the French settlers throughout this book.)

At the time of Camus’s birth, on the eve of the First World War, Algeria was officially a French region divided into three départements (Oran, Alger, and Constantine) and three military zones, all under the authority of a governor-general. In reality, however, there were two Algerias. One was a French region, inhabited by 750,000 pieds-noirs who had all the rights and protections afforded by the French Republic. They were French citizens, equal under one legal system—they had the right to vote and lived under the famous French revolutionary slogan: liberté, égalité, fraternité. In the other Algeria, an occupied territory, there were 4.7 million ‘Muslims’ as the French census called them. These men and women were not French citizens (though they had the obligations of French nationals) and they lived under a set of punitive laws that made it difficult for them to receive an education, to earn a living, to speak their language, to practise their religion, or to own land. (For the purposes of this book, I will call them Algerians (which includes Arabs and Berbers), but the French authorities referred to them most often as indigènes or Muslims.)

The history of France’s involvement with Algeria was nearly 100 years old by the time of Camus’s birth. Algeria was invaded in 1830 by the army of King Charles X, initially as an attempt to create a diversion from domestic challenges to the legitimacy of his regime. After the invasion, France’s presence gradually grew. Until 1870, Algeria was under the control of the French military, governed by a succession of generals. The conquest of Algeria by France was long and drawn out, with some historians estimating that over 6 million Algerians died over the nearly 100 years of occupation.

During the conquest, the French took millions of acres of land from Algerians, uprooting entire crops. (Typically, they replaced olive trees with vines to produce wine for France.) During this period, in pursuit of territorial control, they routinely resorted to razing entire villages and killing many inhabitants (a practice called la razzia) and forcing enemy combatants into caves, the entrances of which they then set on fire, asphyxiating the prisoners inside (l’enfumade). These actions were officially sanctioned by the authorities and praised by prominent intellectuals at the time, including Alexis de Tocqueville, who wrote in a report on Algeria: ‘I believe that the laws of war allow us to ravage the country and that this must be done either by destroying harvests … or by way of these rapid incursions we call razzias …’.

As a result, there were many uprisings and revolts against French rule, the largest of which lasted over six years and was led by Abdel El Kader, who defeated Governor-General Thomas-Robert Bugeaud, before eventually becoming a prisoner of the French in 1847. By 1871, the last of the major Algerian insurrections failed. French civilian governments ruled Algeria for the next eighty-three years, until the first year of the Algerian War of Independence in 1954.

As a child Camus may not have known the true history of France’s conquest and occupation of Algeria. The French educational system put forth an alternative set of ‘official’ facts; ‘it was the indigenous people themselves who provoked France’s attacks on them’ is a standard line from French history books in the 1920s, which consistently praised ‘France’s magnificent colonial empire’ and omitted any mention of the razzias, enfumades, or land confiscations. This lack of acknowledgement continued for many years and France only officially recognized the Algerian War of Independence in 2002.

What young Camus could not ignore and would come to challenge in his mid-twenties was the second-class status of Algerians. After the last insurrection was quelled in 1871 and after the fall of Napoleon III, French-occupied Algeria changed drastically. Under the Third Republic, the military policy of working with Arab and Berber tribal leaders was abandoned, and the new civilian leadership exerted direct control over the Arabs and Berbers via the Code Indigène (literally, indigenous code). In contrast to the famous Code Civil that was and still is the rule of law for French citizens, the Code Indigène, which was put in place in 1881 and only partly revoked by President Charles de Gaulle in 1944, set out punitive laws and regulations specifically for Arabs and Berbers. Just like former slaves in the French Caribbean islands, Algerians needed to obtain a permit to travel outside their villages. Muslim religious practices were increasingly under the control of the French state (for example, many koranic schools were shut down and pilgrimage to Mecca was rarely authorized), and specific tribunals for Muslims, judged by Frenchmen, offered virtually no right of appeal. Non-Europeans had to pay a special supplemental ‘Arab tax’, and Algerians could not vote in any elections.

In the standard playbook of colonial powers, a classic move is to recruit—via the granting of a privileged status—a minority ethnic or religious group to assist in governing the conquered land. France attempted this move with Algerian Jews, though it was far from successful at first. The Jews living in Algeria (called Israélites indigènes by the French government) had the same legal status as Arabs and Berbers and were not considered French citizens. In 1869, they were offered French citizenship, but virtually all declined; most of them spoke Arabic and had no more ties to France than other indigenous people of Algeria; they were Arabs: culturally, ethnically, and linguistically.

The French government, faced with this show of indifference by Algerian Jews, which it took as a rejection, unilaterally proclaimed all Algerian Jews French citizens in October 1870. This famous Crémieux decree of mass naturalization unleashed a torrent of anti-Semitism from the pieds-noirs towards Algerian Jews. The pieds-noirs from virtually all political parties were afraid that the naturalization of Algerian Jews was a harbinger of things to come: in short, that Arabs and Berbers might eventually be naturalized as well, and that their own privileged status in French Algeria would then be threatened.

From 1870 onwards a constant feature of life in French Algeria was virulent and often violent anti-Semitism. There were many ‘anti-Jewish leagues’, and there was even a very popular anti-Jewish party. Pogroms took place in Oran in 1897, and in Constantine in 1934, which resulted in many deaths and mutilations of Jewish Algerians. When Marshal Pétain came to power in July 1940, the Crémieux decree was revoked: Algerian Jews lost their French citizenship and again shared the same status as Arabs and Berbers until the end of the Second World War.

Subject to constant denigration and sometimes violent attacks by pieds-noirs, Algerian Jews were nevertheless legally French from 1870 to 1940. Over time they came to consider themselves as pieds-noirs and many sided with France during the Algerian War of Independence.

Though the French state never considered naturalizing all Arabs or Berbers, the judicial segregation of Algerians via the Code Indigène was concurrent with a policy of incremental integration. This seemingly contradictory objective of integrating a small minority of Algerians in the school system to create a local elite who would then work within and for the French Republic was highly controversial for the vast majority of pieds-noirs. The policy of limited integration meant that Algerians—those very few who could afford the fees for food (and housing if it was a boarding school)—were allowed in public schools, albeit in very small numbers. In Camus’s secondary school class, for example, there were only three Arabs out of thirty students.

Some members of the educated Algerian elite made a militant push for more integration. In 1912, a coalition of this elite was organized as a group called ‘The Young Algerians’, and, led by Benthami Ould Hamida, travelled to Paris to present their ‘Young Algerians Manifesto’. The demands outlined in the Manifesto on the whole did not challenge the French presence in Algeria but did include the abolition of the Code Indigène. The Manifesto was rejected by the French government, but the movement would strengthen into an organized political force in the 1930s. In 1936 Camus himself supported the abolition of the Code Indigène and the granting of citizenship for a small minority of Algerians. He hoped for a time when France’s treatment of Algerians would reflect the humanist rhetoric of the French Republic.

When the First World War broke out in Europe in 1914, France summoned Algerians to join the French army. Few were keen to fight for what they saw as occupying forces. In at least one recorded instance, the population of one region (les Aurès) rose up against the draft. The uprising was brutally repressed, the region was bombarded, and hundreds of insurgents were killed. Of the sizeable contingent of Algerians who fought under the French flag, a disproportionate number died on the battlefields of Europe, as they were routinely sent to the most dangerous combat zones. Still, many pieds-noirs died as well, and Camus’s father Lucien was amongst them.

Camus’s three fathers

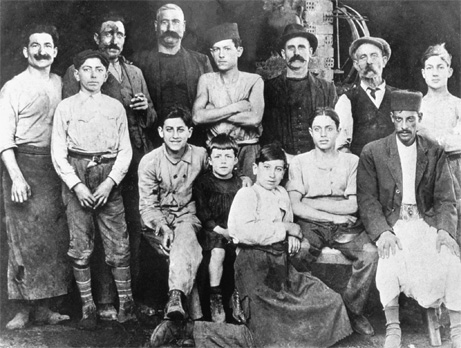

Lucien Auguste Camus died from his wounds in the early stages of the First World War, when his son Albert was only 1 year old. Camus’s mother Catherine, half-deaf and illiterate, was unable to raise her two sons alone. Thus, Camus grew up very modestly in the home of his stern grandmother (Catherine-Maria Sintès), who often beat him and was steadfastly against his pursuing his studies (she was the likely inspiration for the unmourned mother in The Stranger). His uncle, a barrel-maker who could barely speak, also lived with them (he was the subject of a short story, The Silent Men), along with his mother and Camus’s older brother Lucien (see Figure 1). The five members of the Camus-Sintès family lived in a tiny apartment with an outhouse. Camus and his brother Lucien shared a bed in the same room as their mother.

1. In the workshop of Camus’s uncle in Algiers in 1920: Albert Camus (7 years old) is in the centre in a black suit.

With the loss of his father, until then the sole breadwinner in his family, the young Albert was adopted by the French state, and not just symbolically. With their adoption, Camus and his brother immediately became wards of the state (pupilles de la nation), entitling each of them to free medical care for life and a modest allowance. Camus’s mother took up cleaning houses and as a war widow she also received a yearly pension of 800 francs, a modest amount compared to the average monthly salary for a pied-noir, though it compared favourably to the one franc a day Algerian labourers made working in the fields.

Camus would have two major mentors in his youth: his primary school teacher Louis Germain, followed by the philosopher and professor Jean Grenier during his secondary school and university years. Each was to play a critical role in Camus’s life. As Jules Ferry (1832–93), the founder of the French secular, mandatory, and free school system, often stated, ‘teachers are in effect soldiers of the French republic’, whose mission was to be the aide and sometimes the replacement for the head of the family.

In Camus’s posthumous novel The First Man, which was largely autobiographical, there are many references to his relationship with Louis Germain and his role as more than a teacher. Germain took an immediate interest in Camus, coming to his home and giving him private lessons, all free of charge, to help him obtain a scholarship and entry to secondary school (which would otherwise have been prohibitively expensive). Germain was also a stern disciplinarian who often used corporal punishment on his students (including young Albert). When Camus was accepted in secondary school, Germain convinced his grandmother to allow him to attend—even though he would not be working and contributing financially to the household. This young, fatherless boy from the rough pieds-noirs neighbourhood was nurtured and encouraged (sometimes harshly), and finally made it to secondary school on a scholarship and then to the university, all because of Germain’s support. We can imagine that school, and in particular French literature, a subject in which Camus excelled, became a way out of the dreariness of his environment and the relative poverty of his home.

Camus’s gratitude toward Germain was not short-lived: over thirty years later he famously dedicated his Nobel Prize for Literature to his primary school teacher: ‘without you, without that supportive hand that you lent to the poor child that I was, without your teaching and your example, I never would have made it.’

When he was 17, Camus passed the first part of his baccalauréat. This accomplishment occurred in June 1930, during the celebrations of the centennial of the French presence in Algeria. For the now nearly one million pieds-noirs, it was a long party. French authorities organized and funded numerous parades andconcerts, unveiled monuments and plaques, and opened museums, all to the glory of France’s mission civilisatrice (‘civilizing mission’). Even the famous left-leaning French director Jean Renoir was commissioned to make an adventure movie glorifying colonizers (Le Bled). Few of the six million Arabs and Berbers participated. Did Camus join in the celebrations? Little is known of the specifics of his life at this stage save that, like many 17-year-olds, he loved to play soccer for the local team.

Camus started what should have been his last year of secondary school in the autumn of 1930, but his life changed drastically when one day in December he started coughing blood. The hospital’s diagnosis was grim: tuberculosis. Treatment for TB was limited to warmth, rest, and good nutrition, and the disease was a lifelong condition. Many years later, Camus told a friend that on that day in the hospital he was afraid for his life and that the expression on the doctor’s face confirmed his fear. His reaction may have also been the result of his staying in a communal room at the Mustapha hospital: a facility where most patients were Arab. According to one biographer, Camus was frightened by the dismal conditions in the hospital and wanted to go home immediately.

From this time on, Camus had a radically new perspective, one in which the arbitrariness and inevitability of death were impossible to ignore. At only 17, Camus became aware of his own mortality. This sudden awareness of death would have many ramifications. In his first philosophical work, The Myth of Sisyphus, the acute awareness of mortality is inextricably linked to his theory of the absurd. In his fiction as well, the imminence and randomness of death are central: death wantonly applied in Caligula, death as a certainty (but also liberating) in The Stranger, death by disease in The Plague.

His prolonged absence from school led his philosophy professor Jean Grenier to pay him a visit—an unusual move for a professor. During this visit, which was later memorialized by both Camus and Grenier in their correspondence and in Grenier’s memoirs, Camus remained silent and seemingly standoffish, though he would later write that he was simultaneously moved by the gesture and unable to express his feelings. This visit also marked the beginning of a lifelong friendship between the two men. Grenier was perhaps the single most important intellectual influence in Camus’s life, and in his early years he acted as a veritable intellectual and political mentor. Camus would dedicate his first book—a collection of essays titled Betwixt and Between—to Grenier.

Grenier was not just a professor; he was a freethinker who rejected all orthodoxy or system. He had already published two philosophical essays before he met Camus. Crucially, Grenier also had connections in Paris, where he had worked for the prestigious Nouvelle Revue française, a publication which featured the writings of the best authors of what was a veritable golden age of French literature. He knew and had worked with towering literary figures such as André Malraux, André Gide, Henry de Montherlant, and Max Jacob. Grenier’s importance in Camus’s intellectual life is evident in one of his first diary entries, written when Camus was only 19 years old:

… read Grenier’s book. He is in it completely and I feel the love and admiration he inspires in me grow. … Two hours spent with him always augment me. Will I ever realize all that I owe him?

But in the beginning of 1931, there were more immediate and concrete consequences of TB for young Camus. Doctors recommended he leave the cramped apartment on rue Belcour in Algiers, which was no place for extended convalescence. Very soon, Camus moved in with his uncle Gustave Arcault, who also lived in Algiers and was married to Antoinette Sintès, Camus’s maternal aunt. He would never return home. Arcault was an eccentric character, a butcher with a handlebar mustache who spent a lot of time holding court in the local café. Moreover, Arcault was a voracious reader; the works of Voltaire, Anatole France, and James Joyce lined his bookshelves.

Camus read Arcault’s books and lent a hand in the butcher’s shop where Arcault attempted to groom him to be his successor. During his time with the childless Arcault couple, Camus’s life became one of relative affluence compared to his living standards at his grandmother’s home. He had a room of his own, and he ate red meat every day. (Doctor’s orders: in the 1930s French physicians believed that meat was a good treatment for TB.) Reminiscing many years later while being interviewed by a friend, Camus considered Arcault as a ‘sort of’ father figure in his life.

The ongoing threat to Camus’s life of TB was also a liberation. At the Arcaults’ home Camus plunged into his studies with renewed intensity and guidance and support from Grenier. Camus’s outlook had changed as well. He now connected his awareness of death’s certainty with freedom, a central paradox that was at the core of his future works.

After six months of convalescence, Camus returned for his last year of secondary school and was later awarded a scholarship to enrol in a rigorous two-year preparatory programme for the French national university examination. Success in this examination typically led to admission to the elite Parisian school the École Normale Supérieure (ENS), and almost automatically thereafter to the most prestigious posts in the French educational system. But, after his first year at the preparatory school, Camus gave up the goal of admission to the ENS. The second year of the preparatory programme was not offered anywhere in Algeria, so he would have had to live in Paris, a financial strain. His ailing health was also a major obstacle to such a move.

Undeterred by this new setback, Camus continued to pursue different paths and, inspired by Grenier, he seems to have formed his ambition to become a writer in his own right. He continued his studies in Algiers and registered for the equivalent of a master’s degree in literature; however, a year later he would change fields and specialize in philosophy instead. Camus’s decision not to pursue the preparatory classes meant that he lost his premium scholarship and had to find a job. Camus always worked to fund his studies. In secondary school he worked in a grocery store during the summers and later at his uncle’s butcher’s shop, and as a university student he worked as a tutor and spent summers working for the city of Algiers in the office in charge of automobile registrations. Camus disliked this bureaucratic work in particular, which he called mind-numbing. He was perpetually strapped for money, until he married the well-to-do Simone Hié in 1934.

Hié was the talk of Camus’s world, known for her risqué dresses and for her promiscuous behaviour. In the very patriarchal Algiers of the 1930s such behaviour was more than scandalous. Camus took an immediate liking to her, but there was one problem: she was the fiancée of one of his good friends, Max-Pol Fouchet, who was often away on militant errands for the socialist party. Upon his return from such a trip, Camus told Max-Pol that Hié was not coming back to him.

When Camus and Hié married in 1934, Camus was 21 and Hié 20. Hié’s mother was a successful ophthalmologist, and Simone represented another world in terms of values and class—perhaps this was part of her appeal. Certainly, it was a step up in the world for the son of a cleaning lady to marry the daughter of a wealthy doctor. Once they married, Hié’s mother paid for their flat in a nice part of town, close to Jean Grenier. The Arcaults, impressed by the marriage, sent the couple some money and loaned them a car.

From its start, the marriage was tumultuous and featured many breaks and reconciliations. Unlike Camus, Hié failed her baccalauréat and appeared to lack purpose or direction. She was also addicted to opiates. As the marriage went on, her addiction became pronounced and she spent more and more time in rehabilitation centres. In 1936, during a trip to Europe, Camus discovered a letter addressed to his wife from a doctor who supplied her with drugs and who also was obviously her lover. For Camus this was the last straw: their short marriage was for all intents and purposes over; upon returning to Algiers, he moved out. The divorce was finalized in February 1940.

Camus continued his studies in Algiers. He was now well on the way to take another national examination: the agrégation. Passing this crucial exam would have made him—like Jean Grenier—one of the top secondary school professors, a fonctionnaire (employee of the state) with plenty of leisure time to pursue his literary ambitions. For Camus, education and his studies were always essentially just a means to an end: to have time to write. Even his mentor and friend Grenier seemed to have doubts about Camus’s dedication to his studies. Later, in an otherwise laudatory book on his most famous student, Grenier would say that he was ‘not an avid reader’. Nevertheless, Camus was often influenced by the material he studied at university. For example, one of his classes on Roman emperors probably inspired the subject matter of his first play, Caligula, which he began to write around the time he attended the course.

Despite this lack of passion for his studies, in order to sit for the examination Camus had to write a substantial final thesis. It was titled ‘Christian and Neoplatonic Metaphysics: Saint Augustine and Plotinus’. Camus’s authorized biographer Oliver Todd details how Camus did not give proper attribution to many sources, sometimes even passing off other scholars’ work as his own, and concludes nonchalantly that Camus was ‘un pompeur’, French slang for plagiarist. The board (which included Grenier) that read Camus’s thesis did not seem to have been bothered by this transgression: Camus got his diploma.

In the spring of 1936, at the age of 22, with diploma in hand, Camus was ready to sit for the agrégation and join Grenier among the ranks of elite secondary school professors. This was not to happen.

Camus the aspiring writer

The earliest written work we have from Camus consists mainly of papers from his last year of secondary school onwards, which Jean Grenier had encouraged him to submit to Sud (‘South’), the school’s publication. Camus’s published and unpublished pieces from this time demonstrate a romantic outlook: he praised nature, especially the sun and its light, and rejected progress, which he likened to a prison. In a piece on music, he stated that great music and great art could not—should not—be understood.

Already at this early stage his ambivalence toward scholarly, academic knowledge is clear. In one of his early unpublished texts, he imagined a dialogue between a first-person narrator and a madman in which he wrote, ‘refusing to know is a liberation, a definitive step toward the emancipation of the soul’. This glorification of the acceptance of the unknowable announced some aspects of the absurd which he would develop in The Myth of Sisyphus. In another passage from the same unpublished text, the narrator is looking at passers by from his balcony, when the madman admonishes him to disregard these unexamined lives. A much later passage of The Stranger epitomizes this attitude—looking down from a balcony at people predictably going about their lives. These passages, and many others, show that Camus at an early age already felt isolated from people who lived their lives without awareness.

The writing from this period is also quite lyrical. As he searched for a voice as a writer, he tried out many genres: poetry, essays—even a fairy tale. At this early stage in his life, if he were to be compared to a painter, perhaps Camus’s outlook most resembled some of J. M. W. Turner’s more abstract paintings, where the sun’s light overwhelms all else and human beings are comparatively insignificant. Camus’s religion in those days was Art (which he almost always capitalized), and his perspective was very much influenced by proponents of ‘art for art’s sake’. He particularly idolized the 19th-century poet Charles Baudelaire—in fact, there are records of Camus and his friends reciting one of Baudelaire’s poems, ‘The Stranger’. The importance of this poem for Camus is self-evident, because it shares the title and some of the themes of what will become his most famous novel:

—Whom do you love the best, enigmatic man? Tell me. Your father, your mother, your sister or your brother?

—I have neither father nor mother, nor sister, nor brother.

—Your friends?

—You use a word there whose meaning leaves me clueless to this day.

—Your country then?

—I don’t even know which latitude it resides in.

—Beauty?

—Beauty? I would love her willingly, were she a goddess and immortal.

—Gold?

—I hate it as much as you hate God.

—Well! What do you love, extraordinary stranger?

—I love the clouds … the clouds that pass … up there … up there … the marvellous clouds!

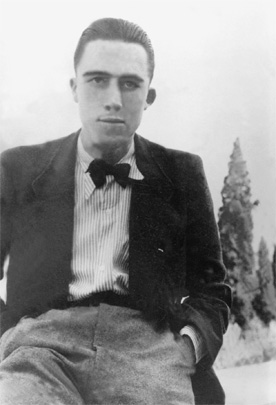

Camus also imitated Baudelaire’s dandyism in dress: he wore bow ties, double-breasted suits, felt hats, and white socks (see Figure 2). This attire gave absolutely no indication of his modest origins, but his writing, although not overtly autobiographical, certainly did. He wrote about his family members, his neighbourhood, and his own life including his experience in the crowded hospital room on the day he was diagnosed with TB. In Betwixt and Between Camus described his life in the small apartment on rue Belcour. The second essay, titled ‘Irony’, describes his family:

2. Albert Camus as a young dandy in Florence.

All five lived together: the grandmother, her middle son, her older daughter, and the two children of that last one. The son was almost mute, the daughter was disabled and it was difficult for her to think. Of her two children, one already worked for an insurance company, when the youngest one pursued his studies.

As in his life, the grandmother dies and his daughter’s youngest son (a stand-in for Camus) feels absolutely no grief. Only the beauty of the sun and of the sky provoke authentic and uplifting emotions in the essay.

In this and other writings, the harshness of daily life and the certainty of death become major themes. But the power and potency of moments of communion with nature remain. Many of his essays juxtapose these seeming opposites: the meaninglessness of a life destined for death and moments of elevated happiness, perhaps even bliss, caused by nature. Camus would famously give these moments of bliss a name: ‘bonheur’. Bonheur is more forceful than its English equivalent of happiness. There is nothing stronger and more positive than those moments of bonheur in Camus’s works: they are the ultimate goal, short-lived but repeatable solace from a resolutely hostile human environment and a meaningless world.

Young Camus and politics

At first it might seem that Camus was apolitical. In his early texts he professed to be against progress and certainly seemed to prefer the writers focused on l’art pour l’art to the artistes engagés, socially and politically committed artists such as those taught in the French schools: Voltaire and Zola. (There is speculation among some Camus specialists that in his secondary school he might have worked as an editor of a small radical pro-independence paper, Ikdam, but no concrete evidence supports this proposition.) There is no record of his being friends or having meaningful interactions with the few Algerian students in secondary school, although he was aware of the Algerians’ plight. Years later, when writing to Grenier about his impoverished youth, he relativized his condition, ‘I was poor, but would have been worse off had I been Arab.’

Seemingly unexpectedly, however, in the autumn of 1935 at the age of 21 Camus joined the Communist Party and was given the task of recruiting Algerian members. There are several possible explanations for this political commitment, which does not seem to follow from his early writings, and which also appears to contradict his later pronouncements against communism and the Soviet Union. Though not a member himself, Grenier encouraged Camus to join the party. The fact that the Communist Party was the place to be for an aspiring intellectual in the 1930s must have influenced Grenier’s recommendation. Many of the greatest names in French literature were either party sympathizers or members, and two of the writers that Camus most admired at the time, Gide and Malraux, were fellow travellers when Camus joined.

But Camus was not a Marxist. Nor was he remotely interested in reading Marx. Camus joined the party in part because it was a place where he could advocate a compromise solution to the growing unrest in certain sectors of the Algerian population. He wanted to promote a gradual integration of Algerians as citizens of the French Republic, was in favour of the abolition of the Code Indigène, and supported the granting of citizenship to a minority of Algerians selected from the elites. This compromise would be a way to counter growing unrest from Algerian political groups vocally demanding independence. The proposal of citizenship for a limited number of Algerians formed the basis of the proposed Blum–Viollette bill, named after French prime minister Léon Blum and the bill’s main sponsor, Maurice Viollette, a former governor of Algeria.

Camus supported the bill enthusiastically. He wrote a petition, ‘Manifesto of Intellectuals in Favour of the Viollette Bill’, in which he urged for a repeal of the Code Indigène, which he called inhuman. Camus also wrote that the bill was in the national interest as it showed the Arab people France’s human face, something that he stated must be done. Thus Camus supported a strategic but problematic position: colonialism with a human face—whose ultimate objective was to safeguard France’s presence in Algeria.

Camus was rightly convinced that refusing to make concessions to the Arab people would have dire consequences for France as a colonial power. This was also Viollette’s position. He issued a stern warning to the pieds-noirs that the lack of a compromise would strengthen the credibility of Algerians in favour of a complete break with France and independence. But the warning went unheeded. Faced with resounding opposition from pieds-noirs, the bill never made it into law and was rejected in the autumn of 1937. The Communist Party also abandoned support of a compromise bill, which led the party to lose some of its Arab members and left Camus demoralized. Whether he left the party or was excluded from it is still a matter of debate, but after the failure of the Blum–Viollette bill, it is clear that Camus had no desire to remain a member.

Camus’s sojourn in the Communist Party permanently influenced his life and artistic endeavours, albeit not in the way the party would have wanted. In what was perhaps the most important legacy of his years as a member, Camus co-founded a theatrical troupe called Theatre of Labour. He co-wrote a militant play about an insurrectional miners’ strike in the region of Asturias in Spain right before the Spanish Civil War (Revolt in Asturias). Although the play supported the insurrectional workers, a striking ambiguity in Camus’s political beliefs began to emerge. The passages that Camus is said to have written (according to the standard French edition) include strong criticism of the violence caused both by the Spanish state and by the miners and their party. In the eyes of Camus, revolutionary violence was just as unacceptable as state violence. For a play written about events on the eve of the Spanish Civil War, which would lead to an upsurge of artistic and intellectual support for the Spanish republicans who fought and lost against Franco, this was a strange position to take. The problem of revolutionary violence was to become a constant in Camus’s works and would emerge in his later debates with Sartre and in his play The Just Assassins.

Camus’s short time as a member of the Communist Party was the first outward manifestation of his acute—but until then hidden—awareness of the injustices of French colonialism. Certainly, by joining the Communist Party, Camus shifted abruptly from a position of silence on colonial realities to a decision to confront them. Yet Camus’s stance was one of compromise: he wanted to reform, to modify colonialism, but he never challenged France’s authority over Algerian land nor was he ever in favour of Algerian independence. His first experience of revolutionary and parliamentary politics made him realize that his goal of a better integration of Algerians to the French colonial system in the face of staunch opposition by the vast majority of pieds-noirs was well-nigh impossible. Camus would later express displeasure when critics mentioned his membership of the Communist Party—not only because he became extremely critical of the Communist Party and of the USSR, but perhaps also because his time as a political militant provided a bleak reminder of the intractable chasm between Algerians and pieds-noirs.

Around the time Camus left the party, he focused on theatre as a playwright and actor. While a member of the Theatre of Labour, Camus had many girlfriends but his real love was Francine Faure, a brilliant student of mathematics and music who did not immediately reciprocate his advances. He courted her assiduously and she would eventually become his second wife.

To make ends meet, he found employment as a clerk with the meteorological institute in Algiers. His literary projects were many: he worked on a play (Caligula), a novel (The Happy Death, published posthumously), and a series of essays (Nuptials) and attempted to launch a literary journal with friends (two issues were published). But, in October 1938, another setback would change the course of his life. Following a compulsory medical check-up on 8 October, the French educational system barred him by law from joining the French civil service because of his poor health. (To preserve state resources, citizens with a short life expectancy could not become government functionaries.) Camus appealed the decision to no avail. He must have felt that all his work from primary school to university was, on some level, meaningless. He would not follow in the footsteps of Grenier after all.

Almost immediately after he learned of his rejection, a crucial encounter would alter his course yet again. That same October, Camus met Pascal Pia, an ambitious journalist from Paris who was tasked with starting Alger républicain, a left-leaning daily newspaper in Algiers. Pia and Camus had a lot in common. Both had lost their fathers at war and were raised by their mothers, and both were admirers of Baudelaire. Pia wanted Camus to be an associate editor and reporter at his paper. Camus, though ambivalent, accepted. (In a letter to Grenier Camus confessed that had he not been rejected by the French civil service, he would not have joined Pia.)

Despite his apparent reluctance, Camus quickly embraced his new position; he worked everywhere on the newspaper: in the printing room, as a copy editor, in the courts, and most famously as an investigative reporter and editorialist. Camus’s involvement with journalism would last the rest of his life. It would lead him to challenge the authorities in many (over 150) articles, and eventually to the editorship of France’s most prestigious resistance paper. However, in 1938, on the eve of the Second World War, Camus was embarking on a career as a bona fide muckraker. His most frequent target? The French colonial administration.