LONDON

Which? |

Oliver Twist by Charles Dickens (1839) |

What? |

Den of grime and crime, where the tale of an orphan augured British social reform |

THIS CITY is a still labyrinth; a confusion of hither-thither streets, grunge and clamour, too many people. The pea-soup fog and miasma of desperation have largely lifted, but many a corner still conjures up the past. When the constant din was of horse-clatter, cab-rattle and peddler-patter. When the streets were packed with prostitutes, pickpockets, fraudsters, gangsters, ragamuffins and the piteously poor. When crime was so rife, your handkerchief might be pinched at one end of an alley and hawked back to you at the other. A city writ larger than life; wondrous and wretched in equal measure …

All of London is laced with Charles Dickens. It seems there’s barely a pub he didn’t drink in, a street he didn’t stroll. Moreover, he painted so strong a portrait of the UK capital at the beginning of the Victorian age that, while the city has existed for over 2,000 years, ‘Dickens’ London’ is the incarnation that most vividly endures.

Charles Dickens was born in Portsmouth in 1812. When his father was sent to debtors’ prison in 1822, young Charles was sent to work at a boot-polish warehouse on Hungerford Steps (now the site of London’s Charing Cross Station). The experience left a lasting impression, fermenting his views on socioeconomic reform and the heinous labour conditions borne by the underclasses – a situation that got worse when the 1834 Poor Law Amendment Act stopped virtually all financial aid to the poverty stricken. At this time, London was the world’s biggest city, an imperial and industrial powerhouse. But it was seething with destitution and class division.

Into this arena came Oliver Twist. Dickens’ second major work, the novel pulled no punches, describing with ruthless satire the levels of crime and depravity rife in the capital. For fictional Oliver – like so many real Londoners – the city’s streets were full of ‘foul and frowsy dens, where vice is closely packed and lacks the room to turn’. Via the tale of the workhouse orphan who ends up embroiled with Fagin’s gang, Dickens shone a gaslight on the horrors of life on the margins in mid-19th-century Britain.

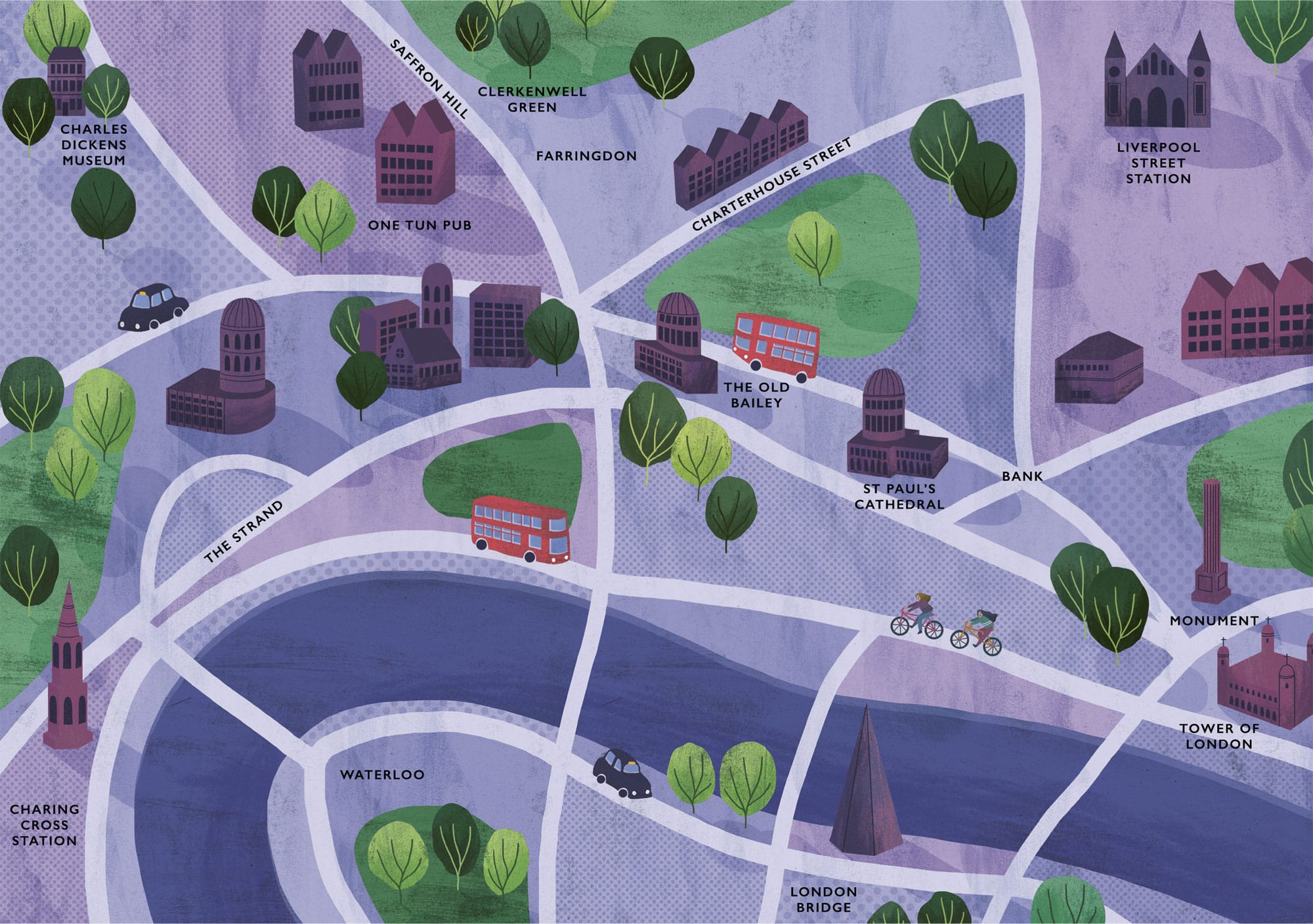

Dickens saw the sordidness first-hand. In 1837 he moved to 48 Doughty Street in Holborn, where he wrote Oliver Twist. Dickens was a great wanderer, and the streets he paced seeped into his pages. And the areas around his former home, which is now the Charles Dickens Museum, still whisper of the past.

A little east of Doughty Street lie the alleyways of Clerkenwell. In the early 19th century this was one of London’s most squalid, crime-ridden neighbourhoods, teeming with thieves and hoodlums. In the 1860s an improvement project cleared the ‘rookeries’ (slums) and Clerkenwell was transformed. However, you can still walk across Clerkenwell Green, where Oliver watches in horror as the Artful Dodger pickpockets Mr Brownlow. And you can still, like Dodger, ‘scud at a rapid pace’ along the nearby alleys towards Saffron Hill. Named for the spice that was grown here in the Middle Ages (to mask the taste of rotten meat), in Dickens’ time this was the site of an infamous rookery beside the sewage-stinking Fleet Ditch. Saffron Hill is now a nondescript sinew of offices and apartments but there’s atmosphere within The One Tun pub. Founded in 1759, but rebuilt in 1875, it’s reputed to be the basis for Dickens’ Three Cripples, the favourite haunt of murderous villain Bill Sikes. Field Lane, the location of Fagin’s lair, was demolished in the clear-up, but probably stood a little south of the pub, near where Saffron Hill meets Charterhouse Street.

Continue further south and you end up before Lady Justice and the Old Bailey, the country’s Central Criminal Court. Part of it is built on the site of Newgate Prison, a gaol since the 12th century, whose ‘dreadful walls … have hidden so much misery’. Dickens witnessed a public execution here, and sent Fagin to its gallows – in Oliver Twist, the bad ’uns get their comeuppance, the good live happily ever after. For Victorian London’s real working classes, life was seldom so fair. But through his words, Dickens ensured they were not ignored.