SOWETO

Which? |

Burger’s Daughter by Nadine Gordimer (1979) |

What? |

Turbulent township at the centre of South Africa’s apartheid-era struggles |

SPRAWLING ACROSS the veld, this confusing, suppurating place sits apart from the bright, big city, separated. not just by geography, but by dilapidation and the sharp end of history. Here in the township, rotten roads crawl through ordered ugliness, row upon row of unlovely houses. Tin shacks lean on each other like drunks; drunks sway between old cars and half-crazed chickens; junk piles up down dirty alleys where tramps forage and stray dogs cock a leg. The air smells of urine, offal, liquor, despair. This is the land across the divide; the black backyard. A dumping ground. A crucible for social change …

In the second half of the 20th century, South Africa was a deplorably fractured nation. The Afrikaner National Party adopted the policy of apartheid (separateness) in 1948, institutionalising existing racial discrimination. People were required to live in areas according to ethnicity; black-only townships were created and millions were forcibly moved. Mixed marriages were prohibited, and schools, buses, even park benches were segregated. Nadine Gordimer’s Burger’s Daughter was published in 1979, when apartheid – ‘the dirtiest social swindle the world has ever known’ – still wracked the country. Initially banned for being dangerous and indecent, it’s a striking work of historical fiction in which the suffering is all too real.

The novel centres on Rosa Burger, daughter of prominent white Afrikaner anti-apartheid protesters Lionel and Cathy Burger – both of whom are imprisoned for their beliefs, both of whom die in prison cells. Rosa has been raised in a highly politicised household in Johannesburg, where races splashed together in the pool and shared boerewors (sausages) and ideologies around the braai (barbecue). With her parents gone, Rosa is forced to find her own identity – but, whatever her personal struggles, she can’t escape the political. Racism is an intrinsic part of daily life at this time. And nowhere is this more evident than in the township of Soweto.

The South West Townships, southwest of Johannesburg, were first created to move blacks away from the city and its white suburbs to areas separated by cordons sanitaires (sanitary corridors), such as rivers or railways. Soweto quickly became the largest black city in South Africa, deprived and angry. Rosa speaks of its ‘restless broken streets’ filled with the ‘litter of twice-discarded possessions first thrown out by the white man and then picked over by the black’. In Soweto, families try to get by in small, overcrowded homes surrounded by ordure, urchins and tsotsi (thugs), while enraged youths denounce the regime. In both real life and Gordimer’s novel, the situation erupted in 1976, when a ruling that the Afrikaans language be used in schools triggered the Soweto Uprising. The riots were violently quashed – 176 students were killed – but trouble continued on and off until South Africa’s first multiracial elections in 1994.

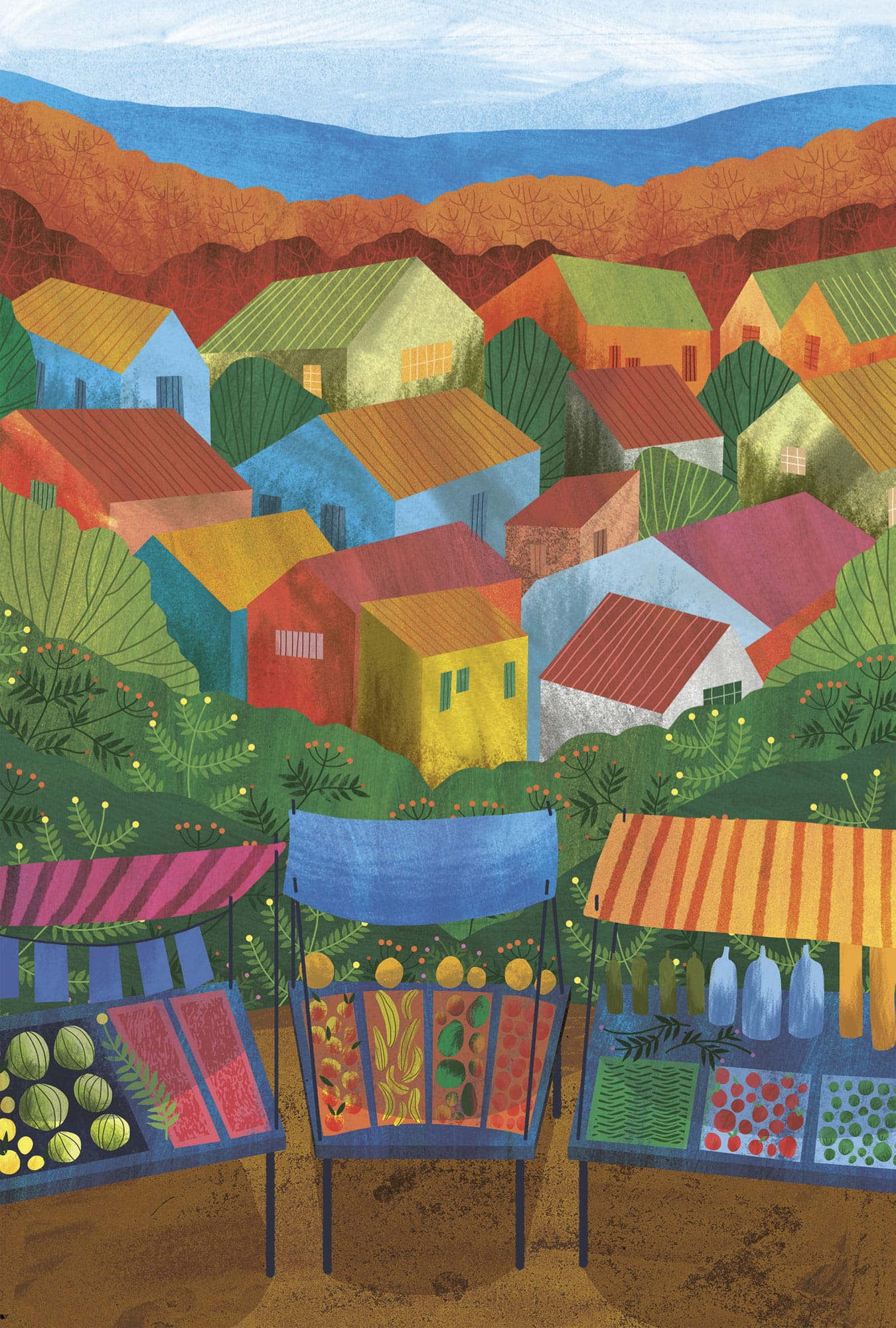

Soweto, like South Africa, has moved on since. The huge township has areas of desperate poverty but also middle-class suburbs and millionaires. And where once only the bravest traveller ventured here, now it’s a Johannesburg must-see. Joining a tour is safest, and will take in key sites: the Hector Pieterson Memorial and Museum, named for the first child killed during the 1976 Uprising; Vilakazi Street, where two Nobel Peace Prize winners – Nelson Mandela and Desmond Tutu – once lived; the graffitied cooling towers of the Orlando power station, now used for bungee jumping. There’s also a chance to see ordinary Soweto – to drink a mug of umqombothi (maize beer) at a shebeen, to join a hallelujah-ing congregation in a tin-roofed church, to browse stalls selling sweets and intestines and ingenious items crafted from trash.

In 1991, the year after Mandela was released from prison and the year apartheid was officially repealed, Nadine Gordimer won the Nobel Prize in Literature for ‘epic writing … of very great benefit to humanity’. Burger’s Daughter merges fiction and fact, using stories to help heal the real world.