HANGING ROCK

Which? |

Picnic at Hanging Rock by Joan Lindsay (1967) |

What? |

Sinister Australian formation where literature has created a new legend |

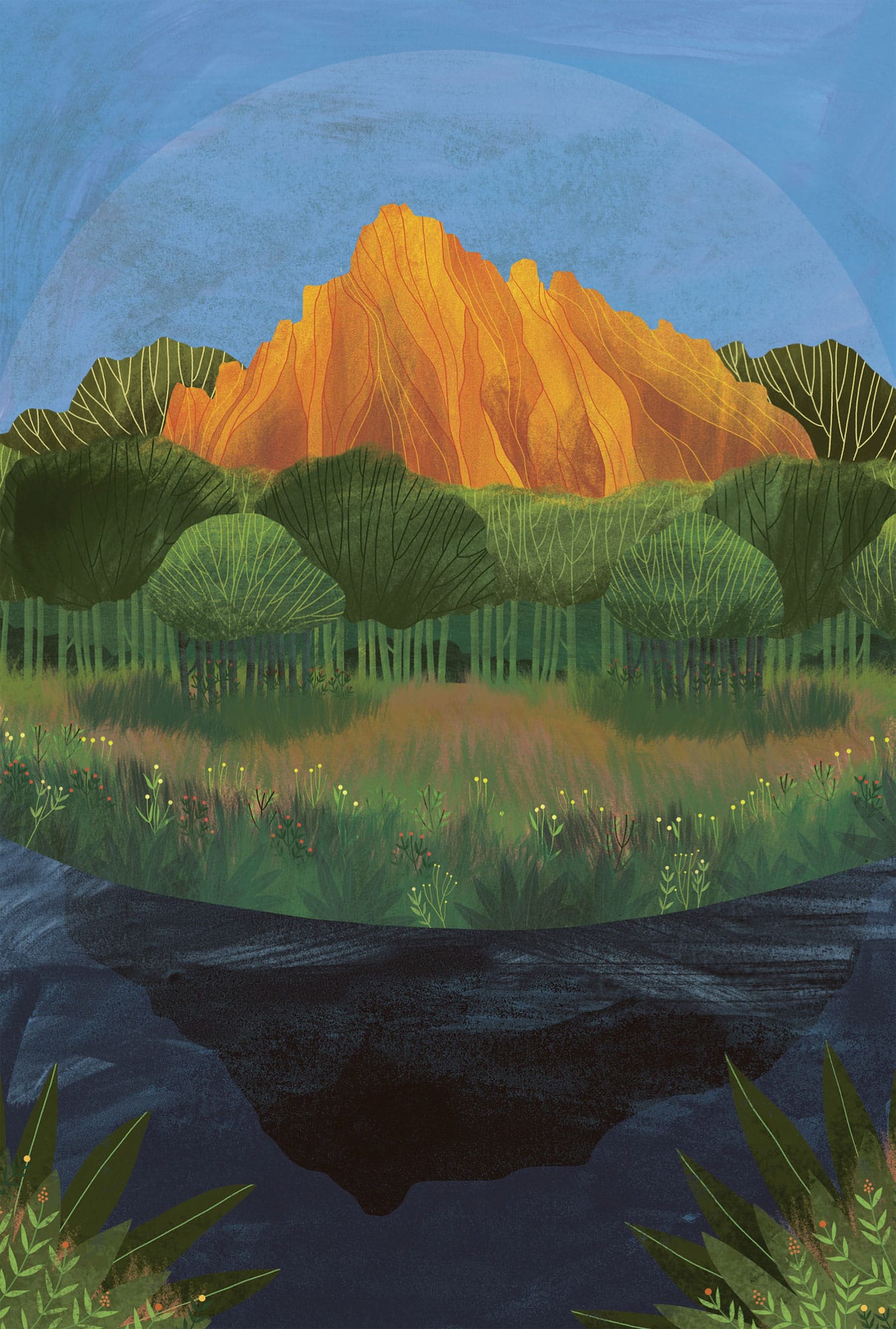

THERE IS the Rock – shrouded in mist, shrouded in mystery. It’s an anachronism in the bush, spewed from the earth’s belly but now rising from the plains like a man-made Gothic castle of towers and crenellations. At first the Rock seems empty, but really it scuffles and creeps: snakes coiled, wallabies hunched, grubs rifling the rotten bark, koalas and kookaburras in the eucalyptus trees. And something else. Something that haunts the inky hollows, something that seems able to stop clocks, chill bones and call young girls to their doom …

Hanging Rock looms large in both the landscape and psyche of Australia. Rare and formidable, it is a mamelon, a mound of stiff magma that erupted, congealed and contracted around six million years ago, and has subsequently weathered to become ‘pinnacled like a fortress’. But Hanging Rock is more than a geological quirk. It’s become a national symbol of the strange, a place where anything might happen – thanks to Joan Lindsay’s classic novel.

According to Lindsay, Picnic at Hanging Rock came to her in a series of dreams, so vivid that when she woke she could still sense the breeze blowing through the gum trees and the laughter resounding through the hot air. It tells the story of a fateful boarding-school outing to Hanging Rock on Valentine’s Day 1900. Four girls and one of the mistresses disappear without a trace, up-turning life at Appleyard College and sending ripples through the wider community. As the book continues, and the mystery remains unsolved, so the ‘shadow of the Rock [grows] darker and longer … a brooding blackness solid as a wall’.

The Rock was a place of loss long before Lindsay’s novel. From the 1830s its traditional owners – the Dja Dja Wurrung, Woi Wurrung and Taungurung tribes – were eradicated from the area, either murdered, killed by disease or forced into Aboriginal reserves. Their ancestors had lived on this land for more than 25,000 years and felt deep connections with what they called Ngannelong; initiation ceremonies and corroborees were held here, important rituals that connected indigenous people to their creator-spirits. Yet in an instant those ancient bonds were severed by European colonisers who’d been here no more than 50 years. Hanging Rock had always been viewed as special, even supernatural; now it was laced with tragedy. The perfect setting, then, for Lindsay’s puzzling, terrible tale.

Some readers have become so obsessed with the myth of the missing girls that, for many, it’s become reality. Lindsay herself was ambiguous. In a brief prologue she states: ‘Whether Picnic at Hanging Rock is fact or fiction my readers must decide for themselves’. Either way, the monstrous Rock is just as the author describes. Located northwest of Melbourne, a little north of Mount Macedon, it rises 105 metres (345 feet) from the Hesket Plains, as extraordinary now as when Miranda, Irma and the rest of the Appleyard girls laid eyes on it over a century ago.

The schoolgirls, surely sweltering in their prim lace collars, corsets and petticoats, travel to Hanging Rock in a covered drag. You’ll no longer kick up fine red dust as you drive the Melbourne–Bendigo road but you could pause, as they did, for refreshment in the village of Woodend – the 1896-built hotel is still a serving brewhouse. And, as you drive, you’ll still look out at the lines of stringy bark trees, cloud-tufted Mount Macedon and, eventually, the terrible bulk of Hanging Rock itself, which sits within Hanging Rock Recreation Reserve.

Like drag-driver Mr Hussey, you could go to the horse races here – the first official meeting was held at the Hanging Rock track in 1886, and continues twice a year, on New Year’s Day and Australia Day. The Reserve also encompasses a visitor centre and, of course, picnic grounds where, like the girls, you can spend an afternoon in exquisite languor, dozing and dreaming, breathing in the wattle and eucalypt, basking with the lizards. There are hiking trails too, leading under the boulders, along precipices and up and around the Rock’s summit, which you can follow. If you dare.