CHILE

Which? |

The House of the Spirits by Isabel Allende (1982) |

What? |

Mysterious Latin nation terrorised by dictators and laced with magic |

THE LANDSCAPE seems but a dream; a hazy memory. The shrouded sky part conceals the fruitful valley, with its twisted vines, dashing stream, distant mountains; only the snow-slathered peak of a volcano stands proud and clear. A vast estancia – a huge swathe of hopeful farmland – lays vague claim to this patch of wildness, but remains at the mercy of Mother Nature in this half-forgotten country at the end of the earth …

Though its location is never stated, La Casa de los Espíritus – The House of the Spirits – breathes Chile. Author Isabel Allende declined to place her story of three generations of the Trueba family; it plays out in an unnamed country in Latin America. But despite its magic-realist flights of fancy and geographic unspecificity, there’s little question of the setting. The novel is part personal saga, part document of the country’s 20th-century history.

Allende has admitted as much; she once said that in writing The House of the Spirits, she ‘wanted to recover all that I had lost – my land, my family, my memories’. The Chilean author had spent long periods of her early life living in Santiago. But when the military coup of 1973 saw the toppling of President Salvador Allende – the world’s first democratically elected Marxist president and Isabel’s first cousin once removed – she fled to Venezuela. The House of the Spirits, which began life as a letter to her dying grandfather, was written while the author was in exile and her homeland – ‘that country of catastrophes’ – was in the grip of Augusto Pinochet’s brutal dictatorship.

The novel begins around 1920, at a time when Chilean politics were in flux. It spans more than 50 years and two main locations: the ‘big house on the corner’, in the centre of the nameless capital, and Tres Marías, the Trueba’s countryside estate. Real events creep into the narrative. The earthquake that tears down Tres Marías and saw ‘buildings fall like wounded dinosaurs’ echoes the 1939 earthquake that devastated Chile, killed nearly 30,000 people and yet caused limited international stir: ‘the rest of the world, too busy with another war, barely noticed that nature had gone berserk in that remote corner of the globe’. Politics are ever present too – from issues of women’s rights and socialism to the build-up to the coup. But there’s also joy and beauty, from the conjured spirits, to the girl with the long green hair to the wild expanses of the sun-baked campo (countryside).

As Allende doesn’t name her country, it’s impossible to follow a Trueba trail with precision. But you might start in Santiago’s Plaza de Armas – the name of many a Latin city’s main square – where violent patriarch Esteban Trueba first sees ‘Rosa the Beautiful’ buying liquorice, and where you can stroll past the palm trees, chess players and towers of the Neoclassical cathedral. You could visit the museum at Las Chascona, former house of Pablo Neruda, who ‘appears’ in the novel simply as the Poet, or the Museum of Memory and Human Rights, which commemorates victims of the Pinochet regime. You might even explore the Brasil and Yungay barrios (municipalities), where the wealthy built fine mansions in the 19th and 20th centuries – less eccentric versions, perhaps, of the twisted, protuberance-encrusted house where clairvoyant Clara Trueba spoke to spirits.

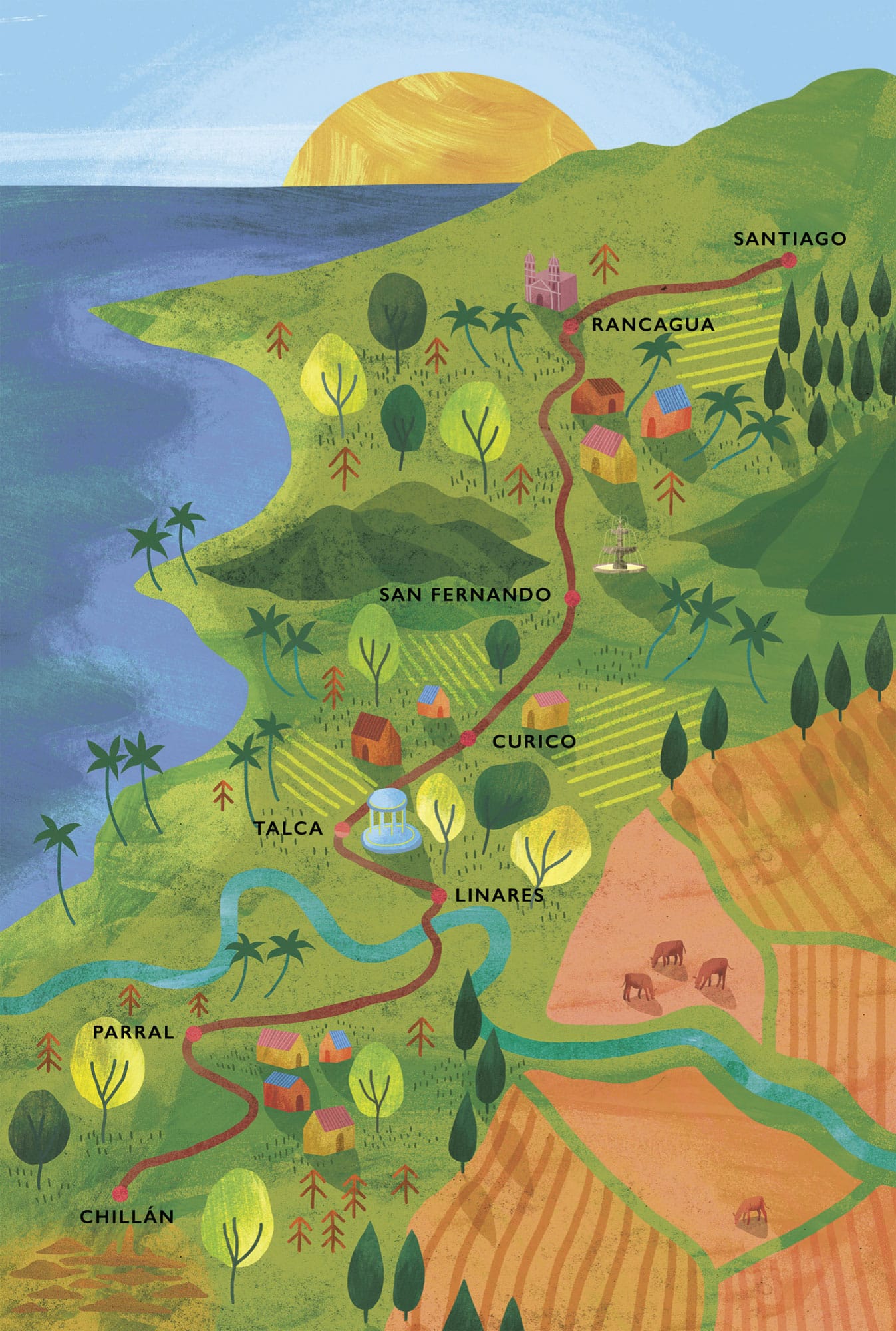

Then, like Esteban, you could leave the metropolis. The Chilean train network has shrunk to a handful of lines, but the southbound service from Santiago’s Gustave Eiffel-designed Alameda Station still offers an escape into the campo. Through the window of the train, Esteban watches ‘the passing landscape of the central valley. Vast fields stretched from the foot of the mountain range, a fertile countryside filled with vineyards, wheatfields, alfalfa and marigolds’. Similarly, the long, thin plain south of Santiago, flanked by the Andes and the coastal range, is Chile’s most fertile region. This rural riot of orchards, pastures and grape-heavy vines – where horse-drawn carts still clop along the highway – is just the place to imagine Tres Marías appearing on the horizon.