On 24 October 1987, the London stock market collapsed. On 25 October the south of England was struck by a hurricane and at 2 a.m. on the twenty-sixth, our first child Noah was born. The midwife wrote in her notes that he had the complexion of ‘peaches and cream’. Love and pride flooded my being, but nothing prepares you for the sheer physicality of childbirth. Once you’ve experienced the torture of your womb reluctantly opening and have seen your enormous belly compressing as your baby slithers, flesh ripping, into the world, your relationship with yourself and with everything around you is forever transformed. You are MOTHER. If you can survive that pain, you can survive anything to protect your offspring, and you will.

The day before Noah’s birth, a Swedish language student answered a card advertising for an au pair that I’d pinned on a notice board in the local church. I called her father for a reference. ‘I don’t know why you’re thinking of employing Maria – she’s never touched a baby in her life.’ he said.

‘Well that’s good, because neither have I,’ was my reply, and wishing us good luck he rang off.

Maria was wonderful and the perfect support. I’d seen many new mothers intimidated when people helping them would tut when the baby’s routine was not strictly adhered to or when standards of sterilising were allowed to slip – I didn’t want to travel down that road.

I would feed Noah first thing in the morning and then walk to the gallery, and Maria would wheel him back and forth to be nursed several times a day. Leaving Noah during the day felt OK at first, but as his needs became more demanding I felt ever more conflicted. During the school holidays, Robert’s mother Barbara came down to London to help, and I loved the pleasure she took in holding our chubby baby in her arms, cooing stories into his ear about the adventures they would share together. Unlike my mother, who was always busy busy, Barbara was relaxed and could focus on helping us transition from being a couple to being a family.

Over endless teas while I nursed Noah, we discussed the trials my poor mother-in-law was experiencing during her marriage to Humphrey. She’d recently made a bid for freedom and had gone to live in a friend’s cottage, but money was tight and she’d been forced to limp back home after breaking her leg. Barbara’s good humour couldn’t conceal the desperation she felt at her imminent retirement.

Barbara insisted that her three home births had provided her most treasured memories, and thanks to this enthusiasm and the fact that Noah’s birth hadn’t exactly been pleasurable, when I got pregnant again eighteen months later, I followed her lead. Planning a home birth was more engaging than the hospital experience – unlike depressing hospital appointments, where I would often wait an hour before seeing a random nurse, my own sensitive and supportive midwife, Katie, would visit me to monitor my baby’s progress and check for potential problems. Meeting at such an poignant moment in my life and sharing my hopes and vulnerabilities created a bond with my midwife that transformed the birth experience.

Planning a home birth is a battle, though – at every turn we encountered people asking whether we’d considered the risks. We would answer with statistics from countries where home births were encouraged, saying that in cases where there are no complications during the pregnancy, giving birth is as safe at home as in any superbug-harbouring hospital. St Mary’s in Paddington was only ten minutes’ drive away, and the maternity unit there had all my notes in case I had to dash there in an emergency. However, I did know that we were taking a risk. If something was to go wrong, the responsibility was squarely on our shoulders.

The baby was due on 20 December. On the eleventh, Robert and I were having supper with friends. Two-year-old Noah was sound asleep, and the Christmas tree was decorated and surrounded by presents. I wallowed on the sofa, barely able to move as we chatted happily about the past year, with the fall of the Berlin Wall and the subsequent collapse of the Soviet Union, and wondered what the coming year held in store. Then the phone rang. As soon as Robert answered, I knew something ghastly had happened. He exploded in grief before the rest of us had any idea of what had been said, kicking furiously at the coffee table and sheering it in half in his pain. Barbara had suffered a catastrophic stroke while writing her Christmas cards.

Robert left immediately and drove through the night to Northumberland, but his mother died before he reached her side. She was sixty-four.

I was nervous about going to Barbara’s funeral so close to my due date, but my midwife Katie assured me that babies have a sixth sense and know when to hang on. Not altogether convinced, Mum and I took the train north with an overnight bag containing some mini nappies and a couple of babygrows.

The ancient church in Mitford echoed with barely repressed sobs. Not only did Barbara’s family and friends attend her funeral; so did a crowd of her former pupils. She had clearly been one of those teachers who would be remembered for life.

I returned home alone and crawled under the Christmas tree to remove the tags from Barbara’s presents, before redistributing them among the rest of the family. I had loved that jewel of a woman completely but, when surrounded by such raw familial sorrow, I felt that I should keep my own grief private. Lying in bed I gave in to silent tears, biting on my knuckles in the vain attempt to protect my unborn child from my sobs.

Ashen-faced with exhaustion though stoic in his sadness, Robert returned to London on 22 December. Early in the morning of the twenty-third, I woke with the familiar gnawing lower-back pain of labour. I didn’t want to wake Robert from his healing slumbers and pottered around the kitchen, leaning over the work surface when the contractions began to build and concentrating on decorating the Christmas cake while breathing out. At 7 a.m. I took him a cup of tea, at which point he took one look at me and quite rightly rang Katie, asking her to come around as quickly as possible.

‘Don’t worry, Rob,’ I said calmly, ‘Noah took hours to commmme…’ But my voice caught and I emitted the low growl of second-stage labour, unable to stop myself from bearing down. ‘Oh my God – the baby is coming now!’

Outside, a storm was in full swing, complete with flashes of lightning and claps of thunder. Electricity in the air set off a car alarm in the street below. Robert’s sister Clare was in the bedroom next door, reassuring Noah that my moans were happy noises and that the storm was Granny Babar sending messages from heaven. Having battled across London in the storm, Katie rushed into our bedroom and found me hanging onto our iron bedstead, my teeth gritted, desperate not to let the baby arrive before she was there. The calm midwife, still wearing her raincoat, placed a reassuring hand on my back and told me to kneel and relax – and out plopped something that looked like a hard ball, completely encased in a slimy membrane. I looked down between my legs at whatever I’d given birth to, which resembled more alien than baby. Katie ripped the sac from its lifeless face and sucked liquid from its mouth. A few seconds later the silence was broken by a gentle mew and she laid the grease and blood-smeared baby on my tummy.

Clare tiptoed in, with Noah in her arms, and they sat on the side of the bed. Noah stared at the slithery creature, with its minuscule fingers and still black eyes, in silent wonderment, cocking his head to one side.

‘This is your baby sister Florence,’ we whispered. ‘You have to take care of her – she’s very little.’ And with that, Noah lost interest and went off to play with his toys.

Rob was understandably shattered, so Clare looked after Noah while I bathed with Florence and wondered how on earth we were going to cope. Then the doorbell rang – I’d forgotten that we’d invited Granny Dock to come and stay for Christmas. Aged ninety-one, she’d flown out to Necker Island to be at Richard and Joan’s wedding, stayed for the celebrations and then come straight back to London to be with us for Christmas. Still shaky-legged, I carried the one-hour-old baby to the front door to meet her great granny. I presumed the elderly lady would be keen for a rest having taken two transatlantic flights in three days and so offered to show her to her room. But she wouldn’t hear of it.

‘Let me look after the baby while you have a rest,’ she said. A few years previously I’d overheard her saying to a friend, ‘I’m not really interested in my great-grandchildren – their genes are too diluted.’

I chuckled as I left her sitting on the sofa, completely absorbed in the hour-old baby on her lap, while I went to bed and had a long sleep. When you have young children, sleep and time to yourself become elusive luxuries and you’d barter a diamond mine in exchange for a single night to catch up on either.

But it wasn’t to be. Just eight months later, I realised I was pregnant once again. Another magical home birth produced another beautiful baby boy, Louis. He had been much wanted, of course – he simply arrived a year or two earlier than ordered! The demands of having three babies in three years stretched us to our limits. Apart from our London household, the new cottage needed our attention and Virgin was going public, putting Robert under untold pressure.

My gallery was also taking its toll. Balancing the needs of the artists, whose livelihoods depended on me, and those of Robert and the children was stretching me to the limit. I finally decided that it was time to call it a day when watching a TV interview with an educated Kurdish man who was fleeing Saddam’s brutal purge. He was cold, penniless, terrified and hungry, and in the face of such oppression, the self-obsessed art of the eighties suddenly felt vacuous. The gallery had to go.

We bought two what only can be described as idyllic cottages, a hundred yards apart and surrounded by fifty acres of fields in Bepton, two miles from Midhurst in Sussex and overlooking the South Downs. One would be for Humphrey and one would be for us.

Our new and ever-present neighbour brought fresh challenges. I couldn’t help thinking that Humphrey’s irascible behaviour – his pedantry, volatility and chaotic lifestyle – may have contributed to the stress that caused Barbara’s blood pressure to reach boiling point. He wasn’t evil and had moments of charm, but these hardly compensated for his inability to control his emotions; I was most troubled by his insensitivity to our need for boundaries and his lack of respect for our privacy.

Rob was conflicted. He felt unable to protect us from Humphrey’s omnipresence and the deadening effect he had on our relationship, and when he saw his father through my eyes, I sensed that he resented me for stirring up long buried feelings of shame.

I wasn’t alone in finding my father-in-law hard to live with. One afternoon, when Humphrey was away for a couple of days, Robert’s forthright Aunt Marion and I went to his cottage next door to pick up his telephone messages. We were inevitably talking about him as Marion sat by the phone and fiddled with the answer machine.

‘Oh Lord, Marion,’ I moaned. ‘I’m not sure I can put up with Humphrey for much longer.’

‘I don’t blame you, Ness,’ she replied. ‘He’s always been impossible and he seems to be getting worse as he gets older. Our mother was to blame – she was so unkind to him as a little boy, but you’d have thought he’d have grown out of it by now.’

‘Just look at this place – it looks as if it’s lived in by a tramp,’ she said, as she stood up from the hall table and reset the machine.

Two days later, Clare called me with panic in her voice. ‘Have you heard Dad’s outgoing answer machine message?’ she yelped.

‘No,’ I said.

‘You’re going to die when you do. Call me back.’

I dialled Humphrey’s number with some trepidation. There was a whirr before the message started: ‘Oh Lord, Marion, I’m not sure I can put up with Humphrey for much longer. I don’t blame you, Ness – he’s always been impossible. Just look at this place – it looks as if it’s lived in by a tramp.’

Too late – Humphrey had already returned home. I walked up to his cottage, saw him sitting in his conservatory and rang his front doorbell, but he didn’t answer. When he appeared two days later, I expressed a genuine apology; he smiled and we said no more. In that moment, my heart bled for this man who had spent his whole life drowning in a sea of emotions, unable to distinguish one from the other.

We found ourselves gravitating towards our friends with young children, who would come to stay at weekends or lived nearby. Shelagh and Navin, friends from our first trip to Necker, had separated and Shelagh was now married to Matthew Bannister, who worked for the BBC. When Virgin Records was sold to EMI in 1992, Shelagh became the company’s head of business affairs, a role which at that time was almost unheard of for a woman. I found it hard to believe that someone as brilliant as her wanted to be my friend, and she became another guide and mentor whom I loved with all my heart.

Our old friends from before we were married – Hamish and Anna, Dr Tim Evans, who was yet to marry Annabel, Nico and Richard Stead, Joey and Richard Oulton, and my old friend Charlotte Hutley, who had married Rupert de Klee – were soon joined by wonderful fellow parents we met through school, as well as artists and work colleagues. Bodley and Sallie Ryle, who lived up in Yorkshire, would think nothing of making the eight-hour round trip to go to a party. Bodley worked in London and in 1984 asked if he could stay with us for a few days a week, just until he found his own flat. Much to everyone’s amusement, Bodley never did find his own flat and has lived with us to this day.

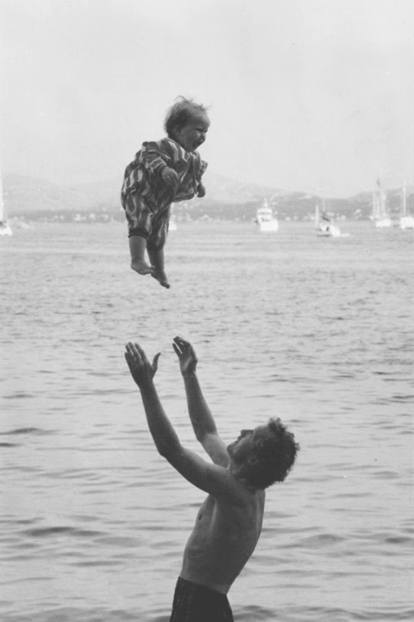

As a group of friends, we embraced the saying that ‘it takes a village to raise a child.’ All our children were almost interchangeable as they rolled around us like puppies. It’s as easy to bath two three-year-olds as one, and laughter made light of the work. Being godparents to each other’s children further reinforced the web that secured us tightly together; the children were able to run free, making dens, inventing games, performing plays and cooking sausages on campfires.

In November 1992, while we were sitting watching Maggie Thatcher droning on about there being no such thing as society, Robert suddenly said, ‘I don’t think I can stand this any longer – let’s go and live in Los Angeles. I’ve got more than enough work to do there. Just for a few months, before Noah has to go to school.’

‘Brilliant idea,’ I replied, rather to his surprise. And on 1 January 1993 we rented our flat and flew to California.

We landed on the first day of the second Rodney King trial, the first one having concluded with the exoneration of the police, which had precipitated the LA riots. Tension was in the air. Our good friend Steve Hendricks, a colleague of Robert’s, welcomed our excited family to the massive white mansion that he and his wife Lisa had embarrassingly rented for us on Beverly Drive. Our other friends the Webbers were also hugely supportive, suggesting nursery schools and places to eat. And of course, this was also Fiona Whitney’s hometown.

‘We can play, Nessie,’ said Fi, now a single mother with two young kids of her own. Memories of our days as a young family in London blur into each other, but taking three months out of our routine ensured that this period of our lives has stayed in my mind. I remember taking Louis as a two-year-old to ‘Mom and Me’ classes with six other tots and their immaculate mothers. In LA the moms talked only of their fears – of germs, of intruders, of wrinkles, of not getting their toddlers into the right schools, of losing their husbands – and their greatest fear of all, of becoming fat.

Years later I wrote a short play called Mom and Me, and our youngest son Ivo staged it at his school. Seeing a group of teenage boys sitting in a circle with dolls on their laps, imitating Californian mothers, highlighted the absurdity of the women’s cares.

I can still see Flo, as clear as day, running naked with Fi’s daughter Charlotte on a chilly, windswept beach in La Jolla, and I also recall receiving a ferocious ticking off from a passing walker, who said she’d report us for child abuse.

‘We’re English,’ we replied.

‘Well, that’s OK then,’ was her reply as she walked off, shaking her head.

Friends and family came to visit, and enjoyed the novelty of our Hollywood lifestyle. Noah proudly introduced his Granny to his class at Beverly Hills Kindergarten. As the children sat transfixed, she was invited to tell them a story. Mum was in her element and started by asking a question. ‘As you can see, I’m a very old lady,’ she said scanning the children’s faces. ‘Now, how do you think I got here?’

A hand shot up in the front and a little girl shouted, ‘On The Mayflower, ma’am.’

‘Not quite,’ laughed Mum, not wanting to humiliate the child.

Another hand shot up before Mum had time to start her story. ‘Can you tell us something else, ma’am?’

‘Of course,’ said Mum.

‘How did you lose your fingers?’

That became the story she told, and the children loved every gory detail.

The day of our departure coincided with the closing verdict in the Rodney King trial, our three-month stay having been dominated by media reports of the case. The anticipation of rioting was reaching a climax, fuelled by the insatiable hunger for drama required by twenty-four-hour news channels. The silence of the empty streets was ominous but we witnessed no sign of unrest as we sped along the empty highway towards LAX.

***

Back in London, not working allowed me to devote my days to family and friends. I missed the gallery, but the insanity of our social life, buying and developing a new house in Notting Hill and weekending in Sussex left little time for much else. Virgin had gone public in 1986 and went private again two years later. Virgin Vision evolved into Virgin Communications, an umbrella company for the parts of the business under Robert’s responsibility. As the government relaxed the broadcast rules and regulations, Virgin Communications started the TV Super Channel and Virgin Radio. Virgin Vision also became involved in post-production and the Internet, in addition to Robert’s already expansive portfolio of businesses.

At this time, the Young British Artists were gaining recognition thanks to the support of a number of collectors, many of whom were encouraged by Charles Saatchi’s high-profile patronage. Michael Craig-Martin was influential in giving the group focus: he tutored a number of the YBAs at Goldsmiths College and has been a loyal godfather to them ever since. Inspired by Damien Hirst’s charismatic leadership, they held a number of exhibitions – their first was Freeze in 1988. London’s cultural currency was rising, and international galleries were opening every week. The focus of auction sales had switched from ‘modern’, meaning post-war artists who were mostly dead, to ‘contemporary’, which meant work by artists who were not only alive, but also alarmingly young.

London was also becoming an international business hub, and it seemed that every high-achieving young couple were coming to live in Notting Hill. Every other stucco-fronted house seemed to be a building site, with the voices of Polish builders echoing within. Our once-rundown and untidy but culturally diverse neighbourhood was transforming before our eyes. Thankfully, despite the odd designer shop appearing on the Portobello Road, the market and the area’s large stock of social housing ensured that it held on to much of its bohemian character.

Back in the 1990s, the social epicentre of our part of Notting Hill was the Acorn Nursery School, opposite St John’s Church on Ladbroke Grove. It was the source of all gossip and intrigue; Ruby Wax, a fellow parent, commented that the Acorn toddler ‘need never schmooze again’. All the connections they could possibly require in life were there at this nursery – for these kids were the offspring of captains of industry, film moguls, writers, models, rock stars, architects, bankers, artists, comedians, broadcasters and entrepreneurs of every description.

Jane Cameron was the school’s founder and head, and we all adored her. The Acorn’s notorious school productions were our social equaliser. It’s impossible to be competitive when you go to watch your little Johnny lisping his way through ‘Thistles, thistles, that’s the meal for me.’

However, the men could really show their worth at the school’s annual charity dinner, when the final lot, a patchwork quilt made of drawings by every child, was auctioned. The big hitters removed their jackets, puffed out their chests and went head to head.

‘One thousand pounds, two thousand, three thousand pounds,’ the auctioneer called out, pointing around the room at a fearsome rate, to gasps from the audience.

‘Four thousand, five thousand, six thousand, seven thousand pounds.’ Glasses were filled, and wives were getting nervous and subtly placing hands on their enthusiastic husbands’ elbows. Bidders dropped out, leaving just two fathers, both determined to get the quilt. The auctioneer, a fellow parent, drew his breath: ‘Eighteen thousand to my left, nineteen to my right and twenty thousand pounds to the bidder on my left.’

The room is silent, as we look from one man to the other. This battle surely must have come to an end? But no – up shoots the hand of the under-bidder and down comes the hammer. ‘Twenty one thousand pounds to you, Paul on my right!’ The room bursts into whoops of applause.

Madness was all around us as house prices rose at an absurd rate, giving us a level of security that we tried not to take for granted. The rises were so rapid where we lived that it felt like we were the one London neighbourhood that didn’t talk about house prices during that decade – the rise was so obscene that to discuss it would have been embarrassing. As the millennium drew to a close, I felt a ghost walk across my grave and shivered as I witnessed the lunacy that was taking hold.