2

THE CORPS OF DISCOVERY

WHAT, EXACTLY, THE BARGAIN CONSISTED OF REMAINED to be determined. The purchase of Louisiana created the American West as it would be understood for the next century. America’s earlier West, between the Appalachians and the Mississippi, was suddenly annexed to the East in the minds of forward-thinking Americans. To be sure, many Bostonians still considered Ohio to lie at the western edge of America, if not of the earth. Eastern provincialism would persist into the twenty-first century. But Jefferson’s bargain, viewed broadly, established a new template for American geography. The country now had two halves, an East and a West, with the Mississippi providing both the line of division and the seam tying the halves together.

Only a comparative handful of Americans—traders working out of St. Louis, mostly—had penetrated much beyond the Mississippi into the new West. Otherwise Louisiana was terra incognita to nearly all but the Indians who called it home. Jefferson set about filling in the blank space on the map between the great river and the crest of the Rocky Mountains. In doing so he diverged still further from the small-government philosophy that had carried him to office, and established an enduring principle of Western history. Development of the trans-Mississippi West would be a top-down affair driven by the federal government. East of the Mississippi, individuals and states had taken the lead in promoting settlement and development. State claims to territories east of the Mississippi antedated the creation of the federal government, which subsequently gave its blessing to the creation of new states but otherwise kept to the rear. West of the river there were no states or state claims; all the land was federal land. The Louisiana Purchase provided Jefferson a tabula rasa on which to write the federal will. As he did so, and as subsequent presidents and Congresses followed suit, they dramatically expanded federal powers. The American West owed its existence—as an American West—to the federal government. And the federal government owed much of the legitimacy and authority it assumed during the nineteenth century to the American West.

As a first step toward promoting Western development—beyond the huge step of the Louisiana Purchase itself—Jefferson persuaded Congress to support expeditions of scientific and geographic discovery into the West. The precedent Jefferson established here, of putting the federal government in the business of sponsoring scientific research and exploration, would far transcend the West and long outlast the nineteenth century; at the two-thirds mark of the twentieth century it would transport Americans to the moon. Congress gave Jefferson money for four expeditions. One would ascend the Red River, another the Ouachita, a third the Arkansas and the last the Missouri. The Missouri was the largest of the tributaries to the Mississippi, and it deserved the biggest expedition.

The Missouri expedition would have an additional purpose. From the headwaters of the Missouri its members would cross the mountains to the Columbia River and trace that stream to the Pacific. The region the Columbia traversed, called Oregon after an old name for the river, wasn’t part of Louisiana. The United States had no legal title to it. But an American merchant captain, Robert Gray, in 1792 had been the first non-Indian to recognize and enter the mouth of the river, which he named for his ship, the Columbia Rediviva. Gray’s feat gave the United States at least as solid a claim to Oregon as those put forward by Britain and Spain, the pushiest rivals, and Jefferson intended to improve the American claim by an exploration of the Columbia from headwaters to mouth. Already the greatest expansionist in American history—a distinction he would never lose—the mild-mannered Virginian audaciously thrust his young republic into the game of empires.

For agent he chose a man he knew well. Meriwether Lewis was the son of two of Jefferson’s neighbors in Albemarle County, Virginia. His father had died when Meriwether was a boy, and his mother and stepfather took him to Georgia, where he learned the ways of the woods and streams. He returned to Virginia to be educated and eventually joined the Virginia militia. He transferred to the U.S. army, ascending to the rank of captain. Jefferson tapped him for a presidential aide, and he came to live in the White House. He and the president shared a passion for science and natural history; Jefferson saw in Lewis a younger, more active version of himself. As important as Jefferson was to the history of the American West, he never personally ventured farther west than western Virginia. Lewis would go where Jefferson did not.

To aid Lewis, Jefferson selected William Clark, a much younger brother of Revolutionary War hero George Rogers Clark and himself a soldier. The choice was potentially problematic in that Lewis had served under Clark in the army; to minimize the awkwardness, Lewis treated Clark as co-commander, though Jefferson still accounted Lewis the leader and Congress insisted on paying Clark at a lower rate.

The president made clear what he wanted from Lewis. “The object of your mission is to explore the Missouri river, and such principal stream of it as by its course and communication with the waters of the Pacific ocean—whether the Columbia, Oregon, Colorado or any other river—may offer the most direct and practicable water communication across this continent for the purposes of commerce,” he said. Getting more specific, Jefferson continued, “Beginning at the mouth of the Missouri, you will take observations of latitude and longitude at all remarkable points on the river, and especially at the mouth of rivers, at rapids, at islands, and other places and objects distinguished by such natural marks and characters of a durable kind as that they may with certainty be recognized hereafter.” Lewis and his corps should learn everything they could about the peoples of the West: “The names of the nations and their numbers; the extent and limits of their possessions; their relations with other tribes of nations; their language, traditions, monuments; their ordinary occupations in agriculture, fishing, hunting, war, arts and the implements for these; their food, clothing, and domestic accommodations; the diseases prevalent among them and the remedies they use; moral and physical circumstances which distinguish them from the tribes we know; peculiarities in their laws, customs and dispositions; and articles of commerce they may need or furnish and to what extent.”

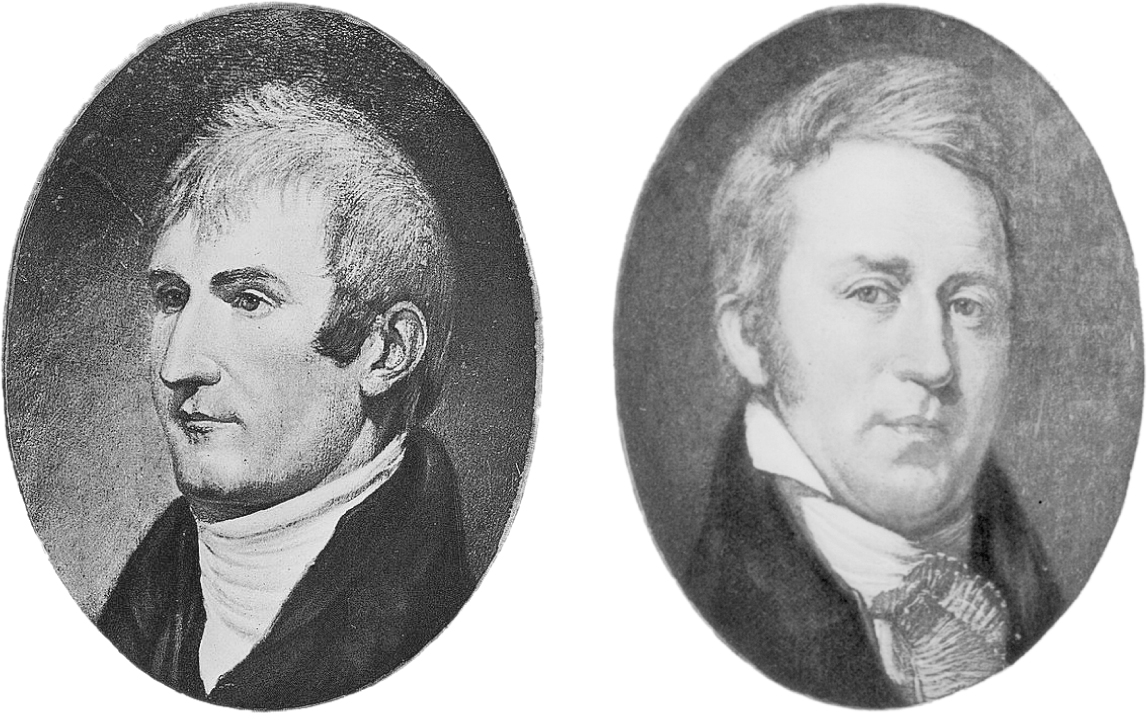

Meriwether Lewis and William Clark. These portraits were painted after the explorers became famous.

Jefferson admonished Lewis to be diplomatic toward the Indians. “Treat them in the most friendly and conciliatory manner which their own conduct will admit,” he said. “Allay all jealousies as to the object of your journey, satisfy them of its innocence.” The Americans came as explorers, not as colonizers; there should be no reason for the Indians to be hostile. Yet if they were, Lewis must be prepared. He should not shrink in the face of challenge. But neither should he endanger his men and the mission unduly. “We value too much the lives of citizens to offer them to probable destruction.” If proceeding became too dangerous, the expedition should turn back.

Jefferson instructed Lewis that he should convey to the Indians that though the Americans came in peace, they also came of right. Louisiana was America’s by right of purchase, while Oregon would be America’s by right of first discovery. Jefferson supplied Lewis with several dozen silver medals showing the president in profile on the front and two hands clasped in friendship on the back. Lewis was to distribute these medals to the chiefs of the tribes he met, explaining that the United States was the sovereign of the West and the president the “great father.”

Jefferson hoped for the best for Lewis but told him to prepare for the worst. “To provide, on the accident of your death, against anarchy, dispersion, and the consequent danger to your party, and total failure of the enterprise, you are hereby authorized, by any instrument signed and written in your own hand, to name the person among them who shall succeed to the command on your decease,” Jefferson wrote.

THE THREE DOZEN MEN OF THE CORPS OF DISCOVERY, AS THE Lewis and Clark expedition was formally styled, left St. Louis in May 1804. The going at first was slow; the expedition’s three boats—a large keelboat and two flat-bottomed pirogues—battled the current of the Missouri for six hundred miles to the mouth of the Platte. Sometimes the wind favored their course and they raised sails to catch it; the rest of the time they paddled, rowed, pulled and pushed against the muddy flow. Lewis often walked the banks collecting specimens; with the boats averaging less than a mile per hour, he didn’t worry about being left behind.

Yet he did worry about not seeing any Indians. An important purpose of the expedition was to cultivate the native peoples, but the native peoples kept their distance, and Lewis didn’t know why. He saw evidence of Indian encampments and, hoping to make contact, sent scouts to track the Indians down and invite them to the corps’ camp. But he got no response. Only at sunset on August 2, near the mouth of the Platte, did a delegation of Otoes and Missouris arrive. “Captain Lewis and myself met those Indians and informed them we were glad to see them, and would speak to them tomorrow,” Clark wrote in the expedition journal. “Sent them some roasted meat, pork flour and meal. In return they sent us water melons. Every man on his guard and ready for anything.”

Lewis and Clark inferred that these were chiefs of some sort but not the principal ones. “Made up a small present for those people in proportion to their consequence,” Clark wrote. The Indians accepted the gift in a friendly manner. Speeches were exchanged, through an interpreter. Lewis closed the parley with more gifts and a display of weaponry. “We gave them a canister of powder and a bottle of whiskey and delivered a few presents to the whole, after giving them a breech cloth, some paint, gartering and a medal to those we made chiefs, after Captain Lewis’s shooting the air gun”—a novel rifle of Austrian design—“which astonished those natives.”

Lewis eventually learned the source of the Indians’ standoffishness. Smallpox had afflicted the region recently and decimated the population. Diseases exotic to America had been the scourge of Eastern tribes since first contact with Europeans in the sixteenth century; the wave of destruction moved inland as the line of contact advanced. Smallpox reached the Missouri by the late eighteenth century, and it left the tribes there vulnerable to enemies and skittish. Those on Lewis and Clark’s route weren’t sure whether the Americans came in war or peace and so approached them diffidently.

ILLNESS CARRIED OFF ONE OF THE AMERICANS TWO WEEKS later. “Sergeant Floyd is taken very bad all at once with a bilious colic,” Clark wrote on August 19. “We attempt to relieve him, without success as yet. He gets worse and we are much alarmed at his situation.” The illness intensified. “Sergeant Floyd much weaker,” Clark wrote the next day. The corps made a start on the day’s journey, with Floyd suffering in one of the boats. “Sergeant Floyd as bad as he can be. No pulse, and nothing will stay a moment on his stomach or bowels.” A short while later Floyd breathed his last. “Sergeant Floyd died with a great deal of composure,” Clark wrote. “We buried him on the top of the bluff ½ mile below a small river to which we gave his name.”

Floyd’s death—likely from a ruptured appendix—reminded all concerned how capricious existence could be in the wilderness. It also underscored the sobering fact that any change in the numbers of the corps would be by subtraction; a man lost could not be replaced.

This fact inclined Lewis to be lenient in a case of desertion. Moses Reed tired of the hard toil up the river and concocted a story that he had forgotten a knife at a previous campground. Lewis gave him permission to retrieve it but soon realized his mistake. “The man who went back after his knife has not yet come up,” Clark wrote. “We have some reasons to believe he has deserted.” The captains allowed Reed another day to make good, and when he still failed to appear, they sent a party in search of him—“with order if he did not give up peaceably to put him to death.”

Catching Reed took ten days, but eventually he was brought in. Lewis conducted a trial in which Reed confessed to desertion and theft of a rifle and ammunition. He threw himself on the mercy of the captains, requesting that they be as forgiving as they could be consistent with their oaths of office. “Which we were and only sentenced him to run the gauntlet four times through the party and that each man with 9 switches should punish him and for him not to be considered in future as one of the party,” Clark wrote.

THE EXPEDITION ENTERED THE GREAT PLAINS AND ENCOUNTERED large herds of buffalo. Lewis looked for the most storied of the northern tribes that lived on these large animals—the Lakotas, or western Sioux. Thomas Jefferson had read of the Sioux in the journals of French traders, and he thought they held the key to American control of the upper Missouri. “On that nation we wish most particularly to make a friendly impression, because of their immense power, and because we learn they are very desirous of being on the most friendly terms with us,” Jefferson told Lewis. Events proved the president too optimistic about the desire of the Sioux to cultivate the Americans, but his assessment of their power was accurate.

At first the Sioux kept away, hunting buffalo and raiding their neighbors. But eventually they made contact. Lewis and Clark learned that a Sioux village was nearby. “We prepared some clothes and a few medals for the chiefs of the Tetons bands of Sioux which we expect to see today at the next river,” Clark wrote on September 24. And so they did. “We soon after met 5 Indians and anchored out some distance and spoke to them, informed them we were friends and wished to continue so but were not afraid of any Indians.”

They got no closer until the following day. “Raised a flag staff and made an awning or shade on a sandbar in the mouth of the Teton River, for the purpose of speaking with the Indians under,” Clark recorded. The five Indians they had seen the evening before approached. “The 1st and 2nd chief came. We gave them some of our provisions to eat. They gave us great quantities of meat, some of which was spoiled. We feel much at a loss for the want of an interpreter; the one we have can speak but little.” They smoked a peace pipe. Lewis started to give a speech but cut it short when he realized his words weren’t getting through.

The chiefs were invited to board the keelboat. They examined various trade items Lewis laid out. He offered them whiskey and almost immediately wished he hadn’t. “We gave them ¼ a glass of whiskey which they appeared to be very fond of,” Clark wrote. “Sucked the bottle after it was out and soon began to be troublesome, one, the 2nd chief, assuming drunkenness as a cloak for his rascally intentions.”

Lewis ordered the chiefs off the boat. They departed angrily, causing Clark to follow them in the pirogue in hope of assuaging injured feelings. This made matters worse. “As soon as I landed the pirogue three of their young men seized the cable,” Clark wrote. “The chief’s soldier hugged the mast, and the 2nd chief was very insolent both in words and gestures, declaring I should not go on, stating he had not received presents sufficient from us. His gestures were of such a personal nature I felt myself compelled to draw my sword. At this motion Capt. Lewis ordered all under arms in the boat.”

A standoff ensued, with both sides glaring. “I felt myself warm and spoke in very positive terms,” Clark recounted. Patrick Gass, one of Clark’s men, recalled, “He told them his soldiers were good, and that he had more medicine aboard his boat than would kill twenty such nations in a day.”

The Tetons probably didn’t get the details of Clark’s boast, which was unclear anyway. He might have been talking about bullets. Or he might have been suggesting that he would unleash an epidemic. The latter threat would have been extremely imprudent, as the experience of others who made such threats would show.

But the Tetons definitely caught Clark’s angry drift, and the confrontation escalated. “Most of the warriors appeared to have their bows strung and took out their arrows from the quiver,” Clark recorded. The Indians wouldn’t let him return to the keelboat, yet he managed to get a message back to Lewis, who dispatched reinforcements. “The pirogue soon returned with about 12 of our determined men ready for any event.”

The Tetons took stock of the situation. They decided not to test the Americans’ resolve and, after some final glares, withdrew. Clark and the others got back safely to the keelboat, which was anchored near a small island. “I call this island Bad Humored Island as we were in a bad humor,” he closed the journal entry for the day.

HUMAN NATURE BEING WHAT IT IS, THE AMERICANS IMPUTED evil motives to the Teton Sioux. “These are the vilest miscreants of the savage race, and must ever remain the pirates of the Missouri until such measures are pursued by our government as will make them feel a dependence on its will for their supply of merchandise,” Clark recorded.

At the same time, he acknowledged a logic in the actions of the Indians, who were protecting their monopoly of trade on the upper Missouri. “Relying on a regular supply of merchandise through the channel of the river St. Peters”—connecting the upper Mississippi with British Canada—“they view with contempt the merchants of the Missouri, whom they never fail to plunder, when in their power.” The St. Louis traders preferred to pay extortion rather than challenge the Tetons, which encouraged the Indians to persist in their racket. “A prevalent idea among them, and one which they make the rule of their conduct, is, that the more illy they treat the traders the greater quantity of merchandise they will bring them, and that they will thus obtain the articles they wish on better terms.”

The immediate question for the Tetons, as for every other tribe that dealt with interlopers like these Americans, was whether their interests would be served better by tolerating the invaders or by attacking them. The Tetons outnumbered the Americans and could have crushed them, though not without suffering casualties of their own. But if this group of Americans was simply the spearhead of a larger force, killing them might be counterproductive. The Sioux had heard enough about the Americans to know that there were very many of them. Perhaps they couldn’t all be killed.

Complicating the matter for the Tetons was a contest within the tribe for political control. Three chiefs—Black Buffalo, Buffalo Medicine and the Partisan—struggled for preeminence. The struggle, which became apparent to the Americans only gradually, caused the Tetons’ attitude toward the Americans to swing between confrontation and accommodation.

Black Buffalo allowed Lewis to approach the Teton village, where a hundred tepees and their several hundred inhabitants attested to the force the Indians could bring to bear against the Americans. But then Black Buffalo and the other chiefs invited the Americans to a grand feast, at which they plied the intruders with great quantities of roasted buffalo meat, delicate cuts of dog, and platters of pemmican and prairie turnips. Male drummers beat a rhythm for female dancers, who waved the scalps of slain enemies in a salute to the martial power of the Sioux, another reminder that the tribe must not be trifled with. The culmination of the evening was an offer of female companionship to the American chiefs. Lewis and Clark declined the offer, to the puzzlement of the Tetons.

Tension suddenly escalated again the next day when Black Buffalo alerted his people that an attack by hostile Omahas was imminent. Two hundred warriors leaped to the ready, armed and eager to fight. But no Omahas appeared. Lewis and Clark considered the matter, then concluded that they had witnessed a manufactured display of force. They didn’t let on. “We shewed but little sign of a knowledge of their intentions,” Clark wrote. Just in case, they conspicuously put their own men on armed alert.

Captains and men kept vigilant till they got past the Teton territory. Lewis and Clark were pleased at having broken through the Sioux barrier. Yet they didn’t fool themselves into thinking they had accomplished Jefferson’s goal of establishing good relations with the most powerful of the upper Missouri peoples.