In 1971, when the Red Army Faction was just over a year old, the members Holger Meins and Jan-Carl Raspe began to make a film about liberation movements and world politics. They sought out Dierk Hoff, a sculptor and welder with ties to Frankfurt’s leftist circles, and asked him to design props for the project: fake hand grenades, pretend pipe bombs, and the like. The film was going to be a

Revolutionsfiktion, a tale of insurgency that would awaken its viewers to the international struggle of the urban guerrilla. This job led to further collaboration, including Hoff’s fabrication of a “baby bomb”: an explosive undergarment fashioned to resemble a pregnant woman’s expanding middle. There is no record of a RAF member infiltrating public space while wearing the bomb, nor is there any of its detonation.

1 But a photograph remains. In it, the bulbous, metal device is strapped onto a young woman’s torso. Loose hair obscures her face, but the pointed cups of her white brassiere are clearly visible. The picture, like the baby bomb itself, made it clear that the Far Left had taken the technology of gender into its arsenal and that it was just waiting for the right moment to use it.

We know that scores of real bombs were deployed in the campaign that the RAF led from 1970 to 1998. In May 1972, for example, the group executed lethal attacks on the U.S. army’s Frankfurt Headquarters and its Supreme European Command in Heidelberg, killing four American officers. The RAF defined itself as an antifascist, anti-imperialist organization engaged in revolutionary violence against capitalism. After the government of the Federal Republic (and the administrations of West Berlin, which, at that point, was an affiliated exclave), the United States and NATO were its prime targets. It is believed that some of Dierk Hoff’s explosives were used in these actions. Hoff disavowed his link to Meins and Raspe shortly thereafter, when the two were arrested together with Andreas Baader, but his small part in the RAF story discloses a truth about the German armed struggle: the force of leftist violence quickly eclipsed the RAF’s subversive intent. Their militancy was always symbolic, but it was also always brutally real.

Klaus Benz, Babybombe (Babybomb), 1976. Published in Der Spiegel 6 (Feburary 2, 1976).

What was the Red Army Faction and which conditions gave rise to it? This chapter outlines the history of the RAF’s emergence and lays the groundwork for an attenuated analysis of postmilitant culture in Germany. It begins with a description of the German Autumn of 1977—the two months when Baader-Meinhof machinations brought West Germany to a state of emergency. The scope then widens to include the social and political shifts that first prefigured this season and later followed upon it. Especially in the “red decade” that led up to the crises of 1977, the German Left underwent a series of reinventions, ruptures, and realignments.

2 The RAF was one product of these breaks, but the group wasn’t the singular culmination of the “cultural revolution,” as the historian Gerd Koenen has termed it, that overtook much of the FRG in the middle years of the Cold War. Indeed the RAF’s actions—and the artistic response to them—can only really be assessed within the larger context of these transformations.

After the siege of National Socialism, Germans from both sides of the country endeavored to build new institutions of democracy. Courts, workplaces, and schools became sites of reconstruction and contestation. The German Left was at the forefront of this critique; two of its constituent groups, critical theorists and feminists, were also the first to perceive the incipient threat of postwar militancy. Their wide-ranging debates about the Far Left offer crucial insights into both RAF militancy and the art and literature that have come After it.

Just as these intersecting historical and conceptual currents provide an important context within which to read the unfolding of the German Autumn, a pair of artworks can be identified as foundational for postmilitant culture and its interpretation. They are the film

Deutschland im Herbst (

Germany in Autumn), released right After the events of 1977, and Gerhard Richter’s cycle of paintings

18. Oktober 1977 (

October 18, 1977), which was completed and first exhibited ten years later, in 1988. Both works reflect upon the difficulty of laying to rest what Klaus Theweleit has called “the specters of the RAF,” and both detect the sexual politics that stirred within the armed struggle.

3 As we shall see,

Germany in Autumn articulates the social questions that shaped leftist agendas in the 1970s, even as it conveys the anxiety and despair that beset so many when the RAF took its suicidal dive.

October 18, 1977 stands at a remove from the conflicts of revolutionary force. Richter foregrounds the aesthetic practice of painting, blurring the margins between document and memory. His choices of subject matter, composition, and technique have become a central reference point for much of the postmilitant culture that has appeared in the decades since he first exhibited the series.

How can a picture or a text take stock of social change, of terrorism, or of symbolic violence? Revisiting Germany’s years of postwar dissent and differentiation, we establish a platform from which to evaluate the capacity of art and literature to represent these phenomena. The long and divergent trajectories of postmilitancy were set by several factors: modern German history, artists’ and writers’ first confrontations with the subject of the RAF, and the proliferation of commentary and scholarship on the significance of militancy and terrorism. The next sections introduce these factors and show how they variously come together and move apart.

1977: The German Autumn

The German Autumn began in early September 1977, when a RAF cell kidnapped Hanns-Martin Schleyer, a former Schutzstaffel (SS) officer and member of the Nazi Party. Although he was interned as a prisoner of war from 1945 to 1948, Schleyer was not punished for his complicity with the Hitler regime. He returned to West German society as a civil servant, worked his way up in the Daimler Benz Corporation during the years of economic recovery, and eventually became the president of the influential Federation of German Industries and the Confederation of German Employers’ Associations. He was slated to serve as Chairman of the World Economic Forum at Davos. To many on the Left, Schleyer was the picture of evil, living proof that the Bundesrepublik had not fully broken with the fascist strains of the Third Reich.

Schleyer’s abduction was preceded by a string of militant and criminal acts. Over the course of seven years, the RAF had used nearly every guerrilla tactic—bombings, robberies, assassinations—in an attempt to make the FRG and its people confront the nation’s legacy of authoritarianism and to resist its integration into NATO’s military industrial complex. Along with these tactics, the RAF exploited opportunities for publicity. In the Schleyer kidnapping, the group videotaped scripted declarations from their hostage, in which he confessed his guilt in Nazi crimes and asked for the release of RAF leaders who were serving life sentences for murder and terrorist conspiracy at the infamous Stammheim Prison. The footage was aired around the world, but when federal authorities refused to negotiate with the terrorists, tensions escalated.

On October 13 a commando of the Popular Front for the Liberation of Palestine (PFLP) hijacked a Lufthansa aircraft with ninety-one passengers and crew, abducting their flight from Mallorca, across the Mediterranean, and into Eastern Africa.

4 Their demand: the discharge of RAF members, whom they considered their comrades in the global anti-imperialist struggle. The hijackers (two women, two men) killed one of the pilots, and the standoff was covered by media agencies around the world. Germans sat riveted to their television sets as Chancellor Helmut Schmidt tried to control the damage. They were conjoined as a national audience for one of the first times since the radio broadcasts of the Nazi period. In the early 1970s, the government began unrolling a program to curtail the Far Left that extended deeply into civil society; it included employment restrictions for suspected radicals, wiretapping, and random house searches. As the German Autumn approached its peak, the shocked public further relinquished even more of their constitutional rights. At the same time, the government imposed a news blackout for extended periods of the Schleyer abduction. Rigorously reported papers scaled back coverage, while the tabloid press capitalized on the explosive stories and images.

On October 17, 1977, almost five days After the high-stakes odyssey had begun, the Grenzschutzgruppe 9 (GSG-9), a West German counterterrorism unit, together with special task forces from Somalia and Interpol, stormed the Lufthansa plane while it was parked at the Mogadishu Airport. Three of the four hijackers were killed in the barrage, but all ninety of the remaining passengers and crew were rescued. When the news broke, the Stammheim prisoners made the final play of their endgame: following a pact, three committed suicide, two by gunshot, one by hanging.

5 They styled their deaths to look like murders, but these acts had the effect of a timed-release suicide bomb—one with repercussions that would last for decades.

6 The next day Schleyer’s body was found dead in Alsace-Lorraine, just over the French-German border; RAF members called the German Press Agency and claimed responsibility for the shooting. The second and third generations of the RAF remained at large, but Germany’s most violent phase of leftist terror was ending. The crises of the German Autumn forced Schmidt and his cabinet into a deadly predicament. Many cite their management of the situation as an inaugural act of West German democracy; others concede that the draconian measures taken to control domestic militancy nearly proved the RAF right: the restrictions of civil liberties disclosed the government’s will toward domination and undermined the ethical principles of the

Rechtsstaat.

7 As the political scientist Herfried Münkler has argued, the asymmetry of the German Autumn—left-wing provocation versus the state of exception invoked by federal powers—prefigured the political conflicts that are part of our current global reality.

8Germany’s spell of leftist militancy and terror was preceded by a long “spring” and “summer” of social and political activism. In the 1950s thousands took to the streets across Western and Eastern Germany and demonstrated against both the rearmament of the Bundeswehr and American military interventions in Korea and Southeast Asia. As ideological contests between the United States and the Soviet Union inscribed deep divisions between the FRG and the GDR, a vibrant New Left movement emerged in the West. The New Left’s ideals of world peace were based on socialist principles, but they departed from the labor-based agendas of hard-line communism. Together with the antiwar and antinuclear

Bürgerinitiativen, other social movements, particularly feminism and environmentalism, added momentum to the New Left.

9 Moving into the 1960s, as the West German economy prospered and the nation entered a new phase of stability, their struggles for social justice made real headway. But dissent among the widening circles of left-oriented West Germans brought about new alignments. The Socialist Student Union (Sozialistischer Deutscher Studentenbund, or SDS) was excluded from the Social Democratic Party in 1961. Together with other activists, they formed the Extraparliamentary Opposition (Außerparlamentarische Opposition, or APO); by the mid-1960s they had a plan to “march” their radical critique through the nation’s institutions. Looking abroad, young people were galvanized by images and reports of the fights for decolonization and civil rights in Africa, Latin America, and the United States.

10 In West Germany, too, a new reality seemed just around the corner.

The Red Decade: 1967–1977

Germans were particularly attuned to the situation in Southeast Asia. In 1965, before many antiwar protests had been waged in the United States, West German leftists organized a series of speak-outs and demonstrations about the political conflicts in Indo-China.

11 Some saw significant parallels between the FRG and South Vietnam: the U.S. military occupied both countries and sought to manage the two “subaltern” governments to its own advantage. Even those who would not acknowledge such a reductive equivalence between the two situations still felt moved to speak out against the U.S. invasion of Southeast Asia. The first Germans to come of age After World War II considered themselves especially obligated to resist all forces of domination. While most took up a pacifist critique of the American occupation, more radical factions adopted violent tactics. Those who would form the RAF moved toward the cutting edge of this formation, but the group’s not-so-distant origins pointed back to the center of the postwar Left.

The Vietnam War evoked several associations for Germans. In his comparative analysis of leftist militancy in the United States and West Germany, the historian Jeremy Varon argues that Vietnam was doubly “coded” for young Germans: they condemned the American military deployment “both in its own right,” Varon stresses, “

and insofar as it recalled Nazi violence.”

12 Ulrike Meinhof also saw a parallel between U.S. bombings over North Vietnam and Allied air wars over Dresden in 1945: both, she wrote, were war crimes.

13 Recently, looking back at the 1960s and 1970s, Birgit Hogefeld, a member of the RAF’s third generation, noted that the analogies between the media images of the Vietnam War and Allied film footage of German death camps could not be ignored. For her and many others, it was “absolutely imperative to take responsibility and to take action.”

14 No one needed to rely on these comparisons in order to oppose the conflict, but the memory of German fascism made the geopolitics of the Cold War intolerable. Radicalized protesters sought to sharpen the contradictions they perceived in their society. They wanted to tempt the German state to react with its full force, and to unmask the violence that subtended its foundations. This, they thought, would generate a revolutionary situation, one that the public could not ignore.

The founding moment of the RAF was conceived and executed by Meinhof. Long active in New Left circles of media and culture, she had taken an interest in the situation of Andreas Baader, publishing articles that commented on (and in some cases validated) his criminal career of auto theft, arson, and other, more pointedly anarchic activities. In the spring of 1970, Berlin authorities caught Baader on the lam and remanded him to a local prison, where he was sentenced to serve out a long prison term for planting bombs in two Frankfurt department stores, an action he had pulled off with Gudrun Ensslin. Meinhof orchestrated a scheme in which Baader would be temporarily transferred to a research institute in Berlin, so that she could interview him for a study on social issues. Authorities granted the request, and Meinhof, with the assistance of three other gun-clad young women, managed to spring Baader back into the radical underground. Shots were fired, and an institute employee was gravely injured, but the operation was otherwise successful. Baader and Meinhof jumped out of one of the institute’s windows and into the headlines of the national media, where their actions—no longer haphazard delinquency, but now considered to be an organized conspiracy—would dominate the news for years to come. Branded as enemies of the state, the militants escaped to safe houses in Berlin and then moved on to Jordan, where they trained with Fatah forces, drilling maneuvers that they would put into practice when they returned home to Germany.

Before the RAF was formed, future members of the group were being initiated into various modes of protest and resistance. In June 1967, during the Shah of Iran’s visit to Berlin, German dissidents demonstrated against unlawful U.S. and British involvement in Iranian affairs. Mohamed Reza Pahlavi’s security detail harassed the crowds with its batons and provoked a violent frenzy—guards pitted against protesters pitted against city cops. The Arab-Israeli War was about to break out, and tensions were high in European cities; record-breaking ranks of police were dispatched to the Berlin demonstration. During the event local officer shot and killed Benno Ohnesorg, a literature student participating in the action. In the days that followed, the public reacted with horror and anger.

15 Where many sensed a general regression toward authoritarianism, Ensslin detected an eruption of state terror that had been lying in wait since the Hitler years. Urging her comrades to resist, she argued that the violence of the FRG government could only be fought with counterviolence. “This is the Auschwitz generation,” Ensslin insisted, “and there’s no arguing with them!”

16In the spring of 1968, as student protests took hold in Paris, Prague, Mexico City, and Tokyo, another lethal outburst punctuated the time line of the German New Left. A young housepainter pulled a gun on Rudi Dutschke, an outspoken leader of the APO, and shot him in the head. Severely injured, Dutschke survived the attack, but the incident provoked massive protests that ranged from journalists’ dissent to destruction and violence. APO members believed that right-wing media forces had endangered Dutschke and other activists; a set of newspaper articles found in the attacker’s possession targeted him as an enemy of the people. Militants staged riots at the Berlin headquarters of the Springer Verlag, which was the publisher of

Bild and other mass-market papers and magazines. In their opinion, these outlets had vilified Dutschke by portraying him as a long-haired, grubby instigator of communism. The revolt interrupted paper deliveries, but it also had broader and deeper effects. Converging with the “Easter March” in 1968 against nuclear proliferation, the APO riots invited the participation of workers who were protesting the Emergency Laws that would secure the government’s increased control in case of war, natural disaster, or public unrest.

Many Germans, including some from the middle of the political spectrum, perceived in the Dutschke shooting the threat of a fascist return and voiced their solidarity with the militants. Meinhof, who joined the anti-Springer riots, wrote extensively about the changed conditions for German activism. She published a series of articles that both lamented the assault on Dutschke and called for Germans to heed the national liberation movements that, to her mind, were poised to change the world: the Tupamaros of Uruguay, the PLO, the Black Panthers, and the revolutionary South Vietnamese. Pulled into the orbit of these movements, Meinhof drew from texts such as Carlos Marighella’s

Minimanual of the Urban Guerrilla and began to imagine the

Stadtguerilla that would take to the streets of Berlin, Frankfurt, and Hamburg, and advance the international struggle for freedom.

17Historians have analyzed newly available evidence that shows the extent to which the RAF was shaped by Cold War contingencies. It received support from the former Soviet Union and cooperated with international terrorist networks in the Middle East and Africa. Examples of this scholarship by Martin Jander, Thomas Skelton Robinson, and Christopher Daase investigate the links between the West German Far Left and the East German Stasi, as well as the PLO and other international militant groups from the 1960s through the 1990s.

18 Using these studies, the historian Jeffrey Herf maintains that the RAF played a role in two intersecting political agendas: the Soviet effort to weaken West German ties to the United States, and the Palestinian effort to weaken the FRG’s support of Israel.

19While it is important to see the RAF as part of a global phenomenon, the aesthetic response to its attempts at revolutionary violence has emerged most intensely within the German world. In the 1960s and 1970s both the radicalization of the Left and the state’s backlash against it triggered debates about postwar national identity that shot through every level of society. The armed struggle was waged in a complex attempt to break off from Germany’s own genealogy of violence. Militants imagined an identification with revolutionaries around the world, but they nevertheless chose local targets and framed much of their rhetoric around national symbols. The RAF’s homeward focus determined its strategy; the literary and artistic responses to its actions, in turn, are inflected with a heavy German accent. We sense this in much of the culture that has followed upon the autumn of 1977.

During and since the “red decade,” the contest for the meaning of leftist terrorism has been fought most visibly in the national media. In their attempts to connect West German daily life with the anti-imperialist struggles of the 1960s, militants made the press one of their prime targets. At the Springer Tribunal—a conference at Berlin’s Technical University in 1968 that kicked off a grassroots boycott of conservative media conglomerates—participants turned the means of film production against their target. The organizers screened one of Holger Meins’s student films, the three-minute

Herstellung eines Molotow-Cocktails (

How to Make a Molotov Cocktail, 1968). The didactic strip follows the instructions set out in Régis Debray’s handbook of guerrilla warfare,

Revolution in the Revolution ? (1967). As it begins, a woman’s hands assemble household items (a bottle, a little gasoline, a rag) into an incendiary device; then they light the fuse. The bomb is passed off to other female figures who set it on fire and take it out into the streets. The final shots are trained on the International Style façade of the Springer Press building.

20The Left’s critiques of the Ohnesorg and Dutschke shootings focused on the institutions that enabled the violence—not only Springer and the other media companies, but also the courts. The legal system that superseded Weimar and the Third Reich still carried with it many traces of earlier legislative structures. The conviction that there were dangerous continuities between the Nazi years and the Federal Republic was one of the central motivators for the broader New Left and the Far Left in particular. The RAF, in its inception, sought to use militancy to counter the authoritarian tendencies that persisted in Germany’s liberal democracy—not only the laws and regulations inherited by the postwar state, but also the sizeable number of people who had perpetrated fascist violence in the 1930s and 1940s and then managed to evade punishment in the new system.

After the assault on Dutschke, many Germans agreed with the New Left’s arguments against retrograde media networks. Prominent figures, including Theodor Adorno, Heinrich Böll, and Alexander and Margarete Mitscherlich, expressed their solidarity in April 1968 by signing an appeal for tolerance and democratic exchange. “Fear and an inability to engage the arguments of the student opposition have created a situation,” the appeal explained, “in which the targeted defamation of a minority incites acts of violence against it.”

21 The signers argued that although the German media was invested with a mandate to uphold the laws of the new constitution, in actuality it was functioning to control an immature and irresponsible public (

unmündige Masse) and bolster a “new, authoritarian nationalism.”

22 This doubt about constraints on civil liberties continued throughout the RAF years of 1970 to 1998. If the mainstream media never quite grasped this, the artists and writers of the postmilitant moment certainly have. The second half of the book analyzes the means by which some of these figures have superseded the critical scope of this media coverage.

The Frankfurt School, Feminism, and the Far Left

Young activists enjoyed the support of the Left’s “old guard” on the Dutschke affair, but relations between the two leftist factions were not always congenial. Many artists, politicians, and public intellectuals who denounced the clampdown on free expression would eventually distance themselves from the protesters, especially when their tactics turned from civil disobedience to the taking up of arms. The rebel youth had a particularly volatile relationship with critical theorists and other left-oriented thinkers and they also clashed with the feminist initiatives that were taking place across the country. Feminists challenged the machismo that was deeply entrenched in the militant underground where the RAF took shelter, as well as the sexist hierarchies that structured much of the New Left.

Beginning in the mid-1960s, a complex interplay developed between young radicals and the Institute for Social Research, the Frankfurt-based group of social scientists and philosophers who returned from forced exile during the war to continue their work on Marxist and neo-Marxist criticism up through and beyond the upheavals of the 1960s and 1970s. Students and activists read the work of the Frankfurt School with great interest, and some public intellectuals affiliated with the institute, particularly Herbert Marcuse, attracted international attention with their defense of radicalism. But others cordoned off critical theory from the strategies of West German militants.

23Adorno was the most prominent of these critics. His writings addressed the historical importance of “advanced” and experimental art and ideas, but his personal and professional politics kept a steadier line. In 1964 a band of activists that included students, workers, and artists instigated a public confrontation with the renowned professor of critical theory. They printed up wanted posters with provocative quotations from Frankfurt School texts and mounted them around the university. The most potent of these citations turned Adorno’s theoretical language against him: “There can be no covenant with this world; we belong to it only to the extent that we rebel against it.”

24 The activists marked Adorno’s name and private address on the posters. They invited the people of Frankfurt to contact him at home and share their views about the antagonisms between theory and practice.

25Few would have paid attention, at first, to the militants’ intervention or realized that the adage was a recasting of words originally written by the surrealist André Breton, but Adorno himself did what he could to put a stop to it. His firm response—to root out the guerrilla poster crew and have its members fined—won him little favor among the dissenters. The media rushed to cover the conflict between the activists and the bespectacled avatar of late Marxism. University lectures by Adorno, Horkheimer, and others were recorded and broadcast on radio and television. Magazine editors published photographs of student-occupied buildings. Stern ran an unflattering shot of Walter Rüegg, the professor of sociology and vice chancellor of the University of Frankfurt: reenacting a skirmish with students, he wielded an upholstered side chair in self-defense. A caption that ran below the picture cited Adorno: “I proposed a theoretical model for thought. How could I suspect that people would want to realize it with Molotov cocktails?” After decades of struggle, scholarship, and exile, when the critical theorists returned to German academia, they were thrust into the spotlight of the mass media. Caught in the glare, the contradictions between the “older” Left and its newer incarnation appeared too great to resolve.

Jürgen Habermas, born between these two generations, was one of the keenest critics of West German militancy. Already in 1967, at an SDS panel about the Ohnesorg shooting, he warned against a “leftist fascism” that would threaten the country’s fledgling democracy.

26 Addressing Dutschke, Habermas dismissed the students’ “voluntaristic ideology” as outdated and uselessly idealistic and called for more reflexive—and modern—strategies for social change. APO members responded by expressing their outrage against the “police state,” its complicity with the nuclear arms race, and the carnage of Cold War conflicts in the global South. They spoke of using “organized irregularity” to foreground the “sublime violence” of bourgeois society, that is, the political and economic forces that connected Berlin to Saigon, to Bolivia, and beyond. Habermas detected a problematic identification with the “third-world” struggles. Later, when the RAF and the PFLP trained their weapons on German noncombatants, the terrorist telos of the urban guerrilla would become only too clear.

Ten years After his debate with Dutschke, Habermas’s critique of German militancy had grown deeper and more complex. In the early autumn of 1977, Habermas published an analysis of the cultural conditions that enabled radical violence. “Die Bühne des Terrors” (“The Stage of Terror”) describes leftist militancy in Europe as a “belatedly bourgeois radicalization” of revolutions that had already come and gone.

27 In the essay, Habermas sees the armed struggle and the government’s reaction to it as a deformation of modern life, one that resembles the “decline” of both the political and the aesthetic orders of experience. Just as the Schmidt cabinet was losing some of its ethical principles and being downgraded to a bureaucracy of public administration (

entstaatlicht), he argued, so was the communicative power of art being obliterated by the onslaught of mass media.

28 The task at hand, then, was to widen the public sphere and make space for fuller discussions of politics, culture, and their various intersections.

Feminists, many of whom shared the critical theorists’ interests in historical and material dialectics, were also concerned about the ways armed resistance might affect the status of women. The postwar

Frauenbewegung was an important element of the social initiatives that motivated much of the New Left. Feminists collaborated in some of the militant actions of the 1960s and 1970s, such as strikes, protests, and the autonomist occupation of condemned residential tracts in Frankfurt and other cities—what was called the

Häuserkampf. And in 1969, a group of women students amplified opposition to the Frankfurt School by interrupting one of Adorno’s lectures, taking off their tops, and flashing their breasts at him. They waved pages torn out of his

Negative Dialectics and reproached him for ignoring sexual oppression in his work. Adorno never recovered from the shock of these confrontations. He canceled his lecture series and died a few months later at the age of sixty-five.

Despite this passing collaboration with the largely male-dominated ranks of the Autonomen and other subgroups that agitated to storm Frankfurt’s university and city center, feminists took their dissent in a different direction. Indeed the break between leftist militancy and the women’s movement is evident in several regards. Feminists didn’t just want to occupy “the house”; they wanted to take it down, defuse the dominant forces that dwelled inside, and assert their own agency. In their revolutionary critique, these women (and some like-minded men) called attention to the personal/political dynamic of German society—the sexism that ran from the middle class right through to the hard core of the Far Left. Feminists surely noted the RAF’s wily maneuvers, such as fashioning baby bombs and planting machine guns in carriages, but they were the first to see the great divide between their own revision of German society and the RAF’s absolute rejection of it. RAF texts make little mention of the Frauenfrage that concerned so many of their generation. The Baader-Meinhof group identified itself with a good number of liberation movements, but they largely ignored feminism.

Turning away from the ascetic nihilism that beset the RAF and other militant groups, German feminists sought to realize many of the New Left’s hopes for social change. In the early 1970s they changed legislation on women’s reproductive rights that dated back a century. One tactic in this project was the publication of Alice Schwarzer’s pioneering article for

Stern in 1971, in which a record 374 women—including many who were prominent in the public sphere—admitted to having terminated a pregnancy. The magazine’s cover was emblazoned with the title “We’ve Had Abortions!” It featured a grid of the women’s identity photos, much like the wanted posters that were at the time one of the most visible signs of national security enforcement.

29 Meanwhile, feminists were active on a number of other fronts. They expanded opportunities for equal employment and developed a woman-affirmative counterpublic sphere (

Gegenöffentlichkeit) that encompassed medicine, urban planning, and, not least, the arts and media. These alternative sites, we will see, became an important reference for some of the most critical postmilitant art.

If Habermas saw politics and culture disparaged and diminished on the Far Left’s “stage” of terror, feminists—like the sculptor and performance artist Rebecca Horn and the writer Verena Stefan—were aware of a related tendency in the experience of sexual desire. Their work never squarely addressed the RAF, but Horn’s “body art” and Stefan’s novel

Häutungen (

Shedding, 1975) turned away from the strictures of militancy and explored erotic and physical sensation. Just as the casualties of the German Autumn began to increase, sexual politics emerged as a major object of interest in public discourse. Feminist papers proliferated in multiple directions of social and political analysis, and in the mid-and late 1970s journals such as

konkret,

Pflasterstrand, and, in the United States,

New German Critique published special issues on sexuality. Most of these texts were written by women, but an important exception to this tendency was Klaus Theweleit’s epic study

Männerphantasien (

Male Fantasies, 1977 and 1978), which critiqued the paramilitary disciplining of male bodies and explored the underpinnings of fascist consciousness. Besides Theweleit, the writing of other men who participated in the debates on gender was generally met with skepticism.

One target of feminist critique was the work of Alexander Kluge, both his books about counterpublic spheres (which he coauthored with his fellow Frankfurt School sociologist Oskar Negt) and his filmmaking, including

Germany in Autumn (which he helped to write, direct, and produce). This response to Kluge prefigures aspects of the postmilitant critique that develops in the rest of this book, so it merits attention. Feminists closely read Negt and Kluge’s

Public Sphere and Experience (1972) and

History and Obstinacy (1981) and used the books’ internal logic to scrutinize the characterization of female figures in Kluge’s early cinema.

30 Noting Kluge’s portrayals of women as “anarchic” or even outright “irrational,” some critics saw these figures as “sensual embodiment[s]” of the utopian drive. Others, however, had their doubts.

31 In an article from 1981 on Kluge’s contribution to

Germany in Autumn, the film historian Miriam Hansen asked whether his characters were scripted to fall short of full agency; she remarked that while his women “succeed in creating their own presence as sensual human beings … they very rarely do as sexual ones.”

32 Kluge’s handling of sexuality is, in fact, uneven at points, but this doesn’t obscure the fact that his films, to an unusual degree, acknowledged the transformative capacity of the 1970s feminism that surrounded the Far Left’s emergence. The films portray women’s dual potential within late capitalist society: their undervalued labor and reproductive power help to maintain the status quo, Kluge suggests, but at the same time their ontological difference places them at the cutting edge of social change. In the language of critical theory, women are resistant to total instrumentalization within structures of domination.

Women in the Picture

In high and mass culture of the West German 1970s, the body—especially the female body—was examined, explored, and celebrated. It was also (no surprise) exploited, but what set this period apart from other moments in modern German society was a heightened awareness of sexual politics. As the historian Dagmar Herzog has argued, the

Frauenbewegung demonstrated by example not only that “human beings” could unite over social problems, but that in fact they could also “be united politically around issues of desire and pleasure.”

33 If this emphasis diverged from the general trajectory of the New Left, it stood in diametric opposition to the Far Left’s terrorist campaign. Most feminist principles were contradicted by the RAF’s agenda, despite the fact that the group was led jointly by women and men. Still, many responses to the German Autumn have conflated feminism and the armed struggle. It is more accurate to argue that the

Frauenbewegung—even in the early days of the late 1960s—unlocked a cultural shift that enabled Meinhof and Ensslin to take control of the RAF. To understand the tensions between the women’s movement and the Far Left, we need to examine the politics and aesthetics of each, and consider how they factor into recent cultural history.

Participating in the gender debates of the 1970s, the art historian Silvia Bovenschen published the widely disseminated essay “Is There a Feminine Aesthetic?” (1976), which drew from Goethe, Freud, and Marcuse to produce a feminist inquiry into modern European culture.

34 Bovenschen’s inquiry can be reframed for an analysis of the Far Left’s own forays into the production of texts and images. Was there a militant aesthetic? RAF documents indicate that there was. The next questions, then, are how this aesthetic played into the group’s program and how it has influenced the art and literature that came After the German Autumn.

Among the RAF leaders, it was Ensslin who most stridently insisted upon the priority of the political in the German armed struggle. “We don’t want to be just a page in the history of culture!” she proclaimed.

35 But the RAF’s dismissal of aesthetic concerns belied the deep interests in art, literature, and ideas that many members maintained, especially in the years before they joined ranks. Ensslin studied English and German at Tübingen and the Free University of Berlin; in the mid-1960s, together with Bernward Vesper, she also founded a small publishing house, the studio neue literatur, which promoted contemporary fiction. Andreas Baader flirted with a career in Munich’s Action-Theater, where he fell under Fassbinder’s sway before taking his antics to the streets. And Ulrike Meinhof served as head editor of

konkret for several years. Before leading the RAF, she also experimented with cinema; she wrote and produced

Bambule, a made-for-television film about insurgency in a girls’ reform school.

36 This early interest in gender, however, would be quickly surrendered to Meinhof’s deeper commitment to the armed struggle.

Later, in the prime of the group’s first generation, the RAF continued to “orient” itself according to aesthetic and especially literary traditions. As the Germanists Gerrit-Jan Berendse and Mark Williams have demonstrated, the Stammheim inmates consulted Brecht’s

The Measures Taken and Melville’s

Moby-Dick for guidance on “proper behavior” while living in a “collective”—that is, the forced constraints of the prison.

37 The Baader-Meinhof group publicly disavowed Western cultural traditions, but in truth the battleground that they plotted out was contoured by aesthetic forces.

RAF texts, many of which were authored by Meinhof and Ensslin but published anonymously, had a distinctive style. Their communiqués with German media and government were often written in lowercase lettering (

kleinschreibung), which was popular at the time.

38 The linguist Olaf Gaetje has recently identified additional characteristics of the Far Left’s pseudo-grammar, including the relatively consistent use of acronyms, enclitics, and logograms such as the symbol + for

und.

39 RAF texts evidence a tendency to simplify German syntax, using parenthetical clauses in lieu of longer formulations. These reductive devices converged with the stylistics of concrete poetry, which called for a revolution in language. In a contribution to

Text +

Kritik from 1970, for example, the writer and linguist Chris Bezzel took a stance consistent with the Far Left’s vision of a new order. The absence of uppercase letters in Bezzel’s writing is particularly notable in German: “what’s revolutionary is a literature that transforms the medium of language itself, that refunctions it, destroying its linguistically hierarchical character. through an innovative play with language, this writing anticipates the social changes that all revolutionaries work for.”

40 In the 1960s and 1970s, many countercultural texts demonstrated an affinity with these stylistics. Indeed the rules and lexicon of this “code” connected a cluster of artists and activists. But the RAF took it to its furthest degree, crafting a language to metonymically signify a radical break not only with “bourgeois” culture, but with German society as a whole.

41 As Andreas Baader put it, “language is action.”

42Bernward Vesper was one of the first writers to enter

kleinschreibung into the register of German literature. Passages of

Die Reise (

The Trip, 1977), Vesper’s largely autobiographical

Romanessay, use the lowercase to chronicle the author’s travels through Germany and across Europe from 1969 to 1971.

43 Although he never joined the Baader-Meinhof group, Vesper was nonetheless linked to it, having closely collaborated with Ensslin, as mentioned above. An editor of the

Voltaire Flugschriften (another key journal of leftist politics and culture), Vesper was also the son of Will Vesper, a prominent Nazi-era writer.

44 The Trip conveys the psychedelic vibe that thrummed around many German radicals. When it first appeared, posthumously, in 1977, the novel was acknowledged as a document of the militant scene that gave rise to the RAF. It begins with the formula “E = Experience × Hatred

2,” passes through smoky meetings of the APO and long Afternoons in Meinhof’s apartment, and ends, more than six hundred pages later, in fragments, aphorisms, and single-line sketches that Vesper took down weeks before his suicide in 1971.

A product of its time,

The Trip is cut across by the question of gender and sexual equality. Vesper conveys his love and commitment to his small son, Felix, the off spring of his relationship with Gudrun Ensslin.

45 But at random intervals he also lets loose tirades of misogynist slurs that were current in the subdialects of the Far Left. The dense fabric of personal and political material in the text also enables Vesper to explore the links between his life and the recent history of German fascism.

The Trip chronicles the extended adolescence of the

Nachgeborenen and also presages tendencies that will develop in the later writing and art that deal with German militancy and terrorism, both at home and abroad.

Since Vesper’s early representation of underground life, impressions of the RAF have appeared in various aesthetic practices—poetry, painting, performance, punk—and their actions have been recorded in historical studies and works of cultural criticism.

46 Within the growing field of RAF-related publishing, a few books have found large audiences over seas, most notably, Bommi Baumann’s

Wie alles anfing (

How It All Began, 1975), an early diary of left militancy, and Astrid Proll’s photo album

Baader-Meinhof: Pictures on the Run, 67–77 (1998), which became a fixture on the coffee tables of left-oriented readers in Germany, North America, and the United Kingdom.

47The Afterimage of the RAF has registered most forcefully in visual art and cinema.

48 The best-known example of postmilitant culture is Gerhard Richter’s

October 18, 1977, a series of paintings that concern the lives and deaths of the RAF leadership. When the cycle was first exhibited, a decade After the German Autumn, it was credited for reawakening the debate about the nation’s confrontation with revolutionary violence, a debate that had become taboo.

49 October 18, 1977 has traveled widely and had a large international viewership. Details from it have adorned the covers of books and CDs, and the paintings are a central reference in Don DeLillo’s short story “Baader-Meinhof,” his first publication in the

New Yorker After September 11.

50 Within the German-speaking world, the significance of

October 18, 1977 is matched by the film

Germany in Autumn. Taken together, these two works illuminate the correspondences between the aesthetic, the social, and the political in postmilitant culture. That these correspondences are deeply inflected by gender make the film and the paintings central to this study.

The fifteen paintings that comprise

October 18, 1977—oil on canvas, of varying sizes—are based on a selection of photographs that includes press shots, forensic documents, and a posed studio portrait. Black and white tints blend into a range of grays, producing images that tend toward abstraction. Titled After the night that Baader, Ensslin, and the fellow RAF member Jan-Carl Raspe died in Stammheim, the series illustrates the arrests and incarceration of the group’s first generation, as well as the suicides and funerals that closed the first chapter of German militancy and terrorism.

51 Richter uses his “photopainting” technique to remarkable effect: the blurred forms draw the viewer into a space between past and present, between document and memory. This blurring has become a signature of the writing and art that touch upon the RAF.

52 The sequencing and repetition of

October 18, 1977, perhaps more than any other Richter work, protract the transposition of film to paint. The curator and critic Robert Storr describes Richter’s technique as pulling forward “the physical reality” of the painting while pushing the image back.

53 As the art historian Benjamin Buchloh has argued in his extended reflections on Richter’s practice, this tension within the work allows us to sense the gap between a set of photographic events and their belated repositioning as works of memory.

54 It also poses a question—central both to the study of European culture After 1945 and to the problem of thinking beyond the militant—about the adequacy of visual art to represent history and its violent traumas.

Gerhard Richter, Tote (Dead), 1988. Part of 18. Oktober 1977 (October 18, 1977). Oil on canvas.

Gerhard Richter, Erhängte (Hanged), 1988. Part of 18. Oktober 1977 (October 18, 1977). Oil on canvas.

Setting October 18, 1977 within the wider currents of postmilitant culture, we begin to see the fading or even absence of certain historical elements within many other aesthetic responses to the German Autumn. Like some of the more recent art on the RAF, the images in the Richter cycle segregate the RAF members from their victims, from one another, and from the social forces that surrounded them. Only one painting, Beerdigung (Funeral), which depicts the procession to the graves of Baader, Ensslin, and Raspe, rejoins the militants into a group. Contemplating the series, we realize that it is not just Richter who detaches the agents of the German Autumn from their context; the RAF members themselves were the first to chart the desolate grounds that the artist depicts. Resorting to terror, the RAF broke from other oppositional networks of its time. Sadly, the RAF’s most significant intervention might well have been its members’ suicides, which cut them off from any shared political praxis and imparted a mythical aura to leftist militancy and terror in Germany.

October 18, 1977 can be both seen and watched. Among the fifteen canvasses, several images recur like frames in a motion filmstrip. Gegenüberstellung (Confrontation), Tote (Dead), and Erschossener (Man Shot Down) appear in multiples of two and three, each reiteration degenerating the picture. Note the paintings’ titles. They omit gendered articles, much like Meinhof’s choice to delete the feminine die from her term Stadtguerilla. Moving along the gallery space, one can imagine various narratives unfolding, quite like cinema, albeit interspersed with blank gaps between the images.

The cinematic quality of

October 18, 1977, as well as its melancholic tone, can be productively compared with the film

Germany in Autumn. Whereas the Richter paintings expose the distance between document and memory, the film focuses on the historical and social contexts of the 1970s.

Germany in Autumn was a defining moment in several ways. First, it marked the shift from the “hot” autumn of RAF actions and the state’s counteroffensive to a cooler climate of conservative consolidation. In September and October 1977 the RAF challenged the West German government’s monopoly on violence and brought the country to crisis. By the next spring the most dangerous elements of the Far Left were either exiled or dead; the wider circles of those who shared many of the RAF’s ideals sat stunned by the militants’ self-destruction and appalled by the state’s severe discipline. For years to come, Amnesty International and other human rights organizations would report on abuses of RAF members and other “political prisoners” who were incarcerated in West German facilities. Heinrich Böll, Jean-Paul Sartre, and other public intellectuals from across Europe voiced concern about the conditions under which these individuals were confined.

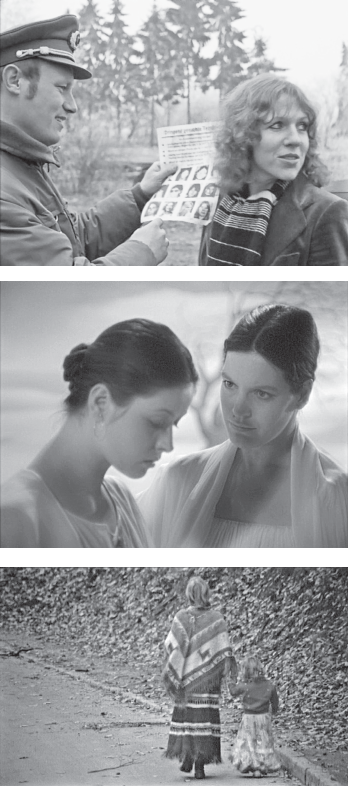

55Comprising both facts and fictions, Germany in Autumn is an omnibus film written and directed by Alexander Kluge together with R. W. Fassbinder, Volker Schlöndorff, and other leading lights of New German Cinema. It was aired on national television just months After the hostage crisis. Germany in Autumn begins and ends with documentary footage, first of Schleyer’s state funeral, and then of the burials of Baader, Ensslin, and Raspe. Both services were performed in Stuttgart, and they took place only two days apart, but as the clips demonstrate, the tone of the two memorials was quite different. Schleyer was accorded national honors, while the burial of the RAF members was attended by enraged protesters and a great show of police officers, reporters, and flashing cameras. Early on, the directors saw that the conflict between the Far Left and the FRG was being waged not only on the streets of German cities, but also in—and through—the national media. This attention to the press and to television links the film back both to the public intellectuals who criticized the biased coverage of student activists in the 1960s and to the RAF itself, which exploited new means of video production in its attack on German society.

As it retrieves disparate archival documents and relates them to other, imagined narratives, Germany in Autumn exposes some of the impasses of 1977. Without trying to resolve these difficulties, the directors sample from a range of cultural and historical materials, leaving it up to the viewer to make some sense of the forces of rogue and state terrorism that both shaped Germans’ collective identity and destroyed individual lives. The film takes an oblique look at the German Autumn, as if to direct the viewer’s attention away from the magnetic images of the militants and onto the social circumstances that, in many ways, influenced the ascendance and demise of the RAF. Of these circumstances, the directors emphasize the shifting sexual politics that shaped German society in the 1970s, from the bohemian communes to the mass market.

Richter, in contradistinction, trains our gaze on the individuals who led the RAF and ultimately gave their lives for it. Nine of the paintings in

October 18, 1977 depict human subjects; interestingly, eight of those nine canvasses take Meinhof and Ensslin as their subject. The gendering of this selection has been discussed by several commentators. Their reflections on the sexual politics at play in the series are useful objects of critique for my own analysis of the way women are represented in postmilitant culture. In an interview from 1989, the critic Jan Thorn-Prikker asked Richter if he focused on Meinhof and Ensslin because the RAF was “primarily a women’s movement.” “That’s true,” Richter replied. “I also think that the women who played the more important role in the group, they made a much bigger impression on me than the men.”

56 There’s a difference, however, between characterizing the RAF as a women’s movement and sensing the impact of Meinhof and Ensslin, as individuals, on the German public. It would be difficult to ascribe any “feminist potential” to the Richter cycle, as the Germanist Karin Crawford has recently done, given the laconic nature of the artist’s remarks in the interview and his continuing insistence that his work be seen as nonideological and apolitical.

57 I would extend this skepticism to any claim that the RAF itself was a feminist initiative.

58 More precisely, we see that Meinhof and Ensslin demonstrated that radical women of postwar Germany had the potential to move history in unprecedented ways, even if this was at variance with their stated intentions.

In her powerful essay about the aesthetic function of analogy in Richter’s painting, “Photography by Other Means” (2009), the film theorist Kaja Silverman enters into the problem of gender in

October 18, 1977 and calls Thorn-Prikker’s account of the RAF “highly revisionist.” She notes that Andreas Baader “presided over [the group] like a primal father, and subjugated [its female members] in crudely gendered ways.”

59 Although anecdotal accounts from those who knew Baader attest to this sexism, and although his prison letters show a misogynist mindset, the fact remains that it was Meinhof and Ensslin who directed the actions of the RAF’s first generation. Besides, in Ensslin’s writings we find the same abusive, antiwoman subdialect used by Baader, Vesper, and many others on the Far Left; Ensslin appropriated these terms for herself and deployed them toward the end of honing the group’s inner core into killer unit.

60 Nevertheless, Richter’s emphasis on Meinhof and Ensslin does signal something important about the art and literature that have proliferated in the wake of the German Autumn. The depictions of RAF women, in

October 18, 1977 as well as in other artworks, are signals of a radical feminism that could have been, but never was. Instead, this feminist potential was derailed by the armed struggle. Thus, it seems that the sorrow conveyed by so much postmilitant culture is for a misplaced militancy. This art and literature prompt us to ask, what if, instead of terrorism, Meinhof and Ensslin had enlisted their followers in a revolution for sexual equality? What if they had chosen other means of resistance, other opponents?

Deutschland im Herbst (Germany in Autumn), dir. Alf Brustellin, Rainer Werner Fassbinder, Alexander Kluge, et al., 1978. Film stills.

This question is implicit in

Germany in Autumn. Female characters dominate the documentary clips and fictional vignettes that thread through the film. At the beginning, the directors Bernhard Sinkel and Alf Brustellin introduce the character Franziska Busch, a filmmaker who interrupts her work on a project about German history in order to help a friend escape from her abusive husband. Later, Hans Peter Cloos and Katja Rupé sketch out a female musician who takes a suspected terrorist into her home. And Volker Schlöndorff and Heinrich Böll invoke

Antigone: the segments they jointly created are a parody of a producer’s failed attempts to broadcast the Sophocles drama on national television shortly After the events of October 1977. The Antigone figure exerts a centripetal influence over the multiple elements of

Germany in Autumn.

61 Just as her defiance prefigures the challenge of the women’s movement, the funerary ethics of the play correspond to the dilemma of how to commemorate the deaths of RAF members and their victims. As we will see later in this book, Antigone is one of the muses of postmilitancy.

Cultural Fallout

October 18, 1977 and

Germany in Autumn establish a framework through which to critique the cultural response to the German armed struggle. The Richter paintings mark the distance between artistic expression and historical event, that is, they plot out the space between the aesthetic signifier and that which is signified.

Germany in Autumn, meanwhile, reveals a third term that mediates between the aesthetic and the political: the social initiatives, particularly the women’s movement, that were a progressive force in German culture of the 1970s and 1980s. As the film ends, it features an extended take of a young mother and her small daughter leaving the RAF funeral procession and hitching a ride from the side of the road. By today’s standards, this closing shot seems dated, but in it we see hopes for a feminist future, one that would both testify to the traumas of the German Autumn and look beyond them toward a new season of social change. Comparing

October 18, 1977 to

Germany in Autumn, we see two divergent currents of postmilitancy, one more conciliatory, the other more critical and resistant. The Richter paintings indicate their temporality posterior to the acts of the RAF. Even as they uncover certain repressed memories of the nation’s past, they also elide many questions of context and agency, and so render a depoliticized vision of the armed struggle.

Germany in Autumn, meanwhile, looks for something to take away from this violent passage in German history. The directors collaborated to redefine militancy and drew out lessons from it that remain salient today.

The many works that respond to the rise and fall of the RAF convey the lasting resonance of leftist militancy and terror, both in Germany and abroad. While some of these productions attempt to master the past, others recharge questions about power and representation that have, to a large extent, dominated European thought in recent generations. At the same time, the works considered here motivate us to rethink certain premises of both Frankfurt School thought and feminist theory. The task, now, is to investigate the operations of postmilitant culture. As the sociologist Donatella della Porta has noted, “the German Autumn and the 1970s more generally have been overcome, but [they were] never really discussed [or] understood.”

62 The attempt to make sense of this period takes place in the writing and art examined in this book. The next chapter furthers this project by comparing several texts—fictional and documentary—that link the legacies of the Far Left to the two most violent episodes of state terror in Germany, the Nazi period and the years of the GDR regime. Reading these narratives “in reverse,” we gain a better grasp on the politics of memory that play out in the postmilitant moment.