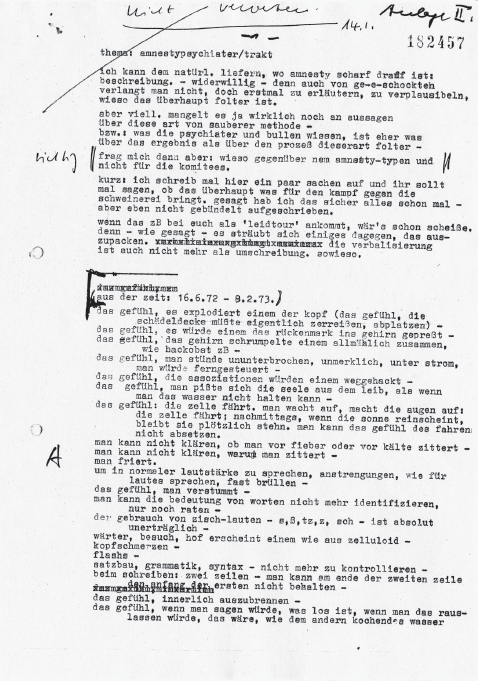

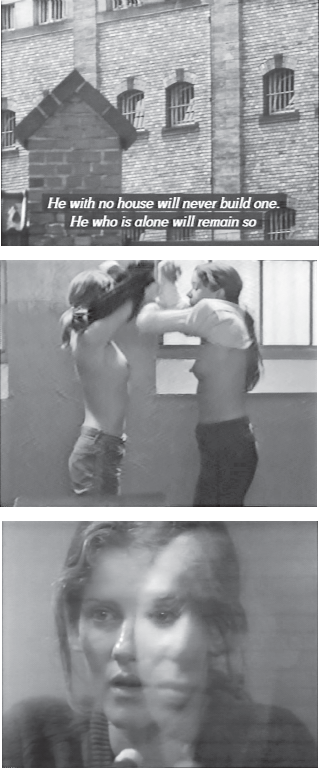

For eight months, from 1972 to 1973, Ulrike Meinhof was held in solitary confinement in the Women’s Psychiatric Section of the Cologne-Ossendorf Prison. While incarcerated, she wrote many notes and letters. On a typewritten page from that time she describes her reduced life in the toten Trakt, or dead section of the prison.

Wardens, visits, courtyard seem made of celluloid—

Headaches—

flashes …

the feeling that time and space are interlocked[,]

that you are caught in a time loop—

Meinhof’s incarceration put a halt to her engagement in the armed struggle. Constantly exposed to fluorescent light, separated from other inmates in a soundproofed cell, she lost her sense of location and began to detach from the material world. As Margrit Schiller, another RAF member, recounted in her memoir

Es war ein harter Kampf um meine Erinnerung (

It Was a Real Struggle to Remember, 1999), the voids of the dead section depleted prisoners’ abilities to “distinguish internal perceptions from external reality.”

2 The austerity of internment delivered Meinhof into an altered state: the silence, the stillness seemed to cordon off a space outside of history, and she began to see the confines of her cell dissolve into a surreal figment. As Meinhof’s distorted perceptions transubstantiated the prison architecture, reducing cubic space to two dimensions, her life shift ed down to the horizontal and vertical of a celluloid filmstrip, and then slowed to a still frame.

Ulrike Meinhof, “aus der zeit 16.6.72–8.2.73” (“from the period of 6.16.72–2.8.73”), 1972–73. Page from prison notebook, MeU 009–002, Archive of the Hamburg Institute for Social Research (HIS Archiv), Hamburg.

Margarethe von Trotta’s feature film Die bleierne Zeit (Marianne and Juliane, 1981) reenvisions the circumstances that Meinhof describes in her writings, the concrete constraints of the prison complex and the psychological strictures of forced isolation. It navigates the controlled space at the intersection of these two conditions, surveying the prison grounds and illuminating the surfaces of its enclosures. Although the film draws elements from the biographies of several RAF militants, Marianne and Juliane most closely follows the life, incarceration, and death-in-captivity of Meinhof’s comrade, Gudrun Ensslin. The composite character is called Marianne; her experiences are chronicled by her sister, Juliane. In a series of flashbacks, von Trotta develops a cinematic bildungsroman about the fictional sisters: born just before the bomb raids of World War II, they come of age in the somber years of the 1950s, and then are startled into social action by the turbulence of 1968. In the late 1970s, when the film approaches its climax, Juliane has become a grassroots activist and an editor of a feminist magazine. Marianne has been charged as a terrorist and imprisoned in a modern, maximum-security facility modeled After Stammheim, the jail that held Meinhof and Ensslin when they died and that has become a central reference in postmilitant culture. The film looks back over this past from the so-called bleierne Zeit, or “leaden time,” that followed the perceived failure of the student movement and, especially, the German Autumn of 1977, when many on the Left surrendered to melancholic resignation.

Marianne and Juliane dramatizes this season of introspection and discontent and refracts Germany’s ongoing process of

Vergangenheitsbewältigung, or “coming-to-terms with the past.” Von Trotta structures the narrative with carefully composed images of the built environment, training the viewers’ attention on the correspondences between external spaces and internal enclosures. Using wide pans, she connects different sites and temporal moments, a technique that lays bare the links between the prison institution and the generic modern condition that Guy Debord and the Situationists gave witness to. Her direction portrays the poetics of the RAF’s failures: the female terrorist stands as a metaphor for the marginalized and insurgent forces of the oppressed; Stammheim, meanwhile, functions as a metonym of the West German police state.

3 Together, these tropes present questions about dominance and victimization that were central to discussions in the 1970s and 1980s about the history of postwar Germany and, more precisely, women’s position within it.

A number of cinema scholars have written about

Marianne and Juliane. The first waves of reception focused on the gender dynamics of von Trotta’s narrative, and the project has long stood as a beacon of feminist filmmaking. More recently, critics have begun to study

Marianne and Juliane from other angles.

4 Karen Beckman, for example, introduced the concerns of art history and architecture into the scholarship of von Trotta’s work. In her analysis of

Marianne and Juliane, published in 2002 in

Grey Room, a journal on the politics of art, architecture, and media, Beckman considers “building relations” in the wake of the World Trade Center attacks. But instead of elaborating a spatial analysis of the film, she concentrates on the possible parallels between the two sisters and the twin towers.

5 It remains to be examined how von Trotta’s concern with the built environment informs her response to both the German Autumn and the FRG’s technologies of surveillance, control, and counterterrorism.

The film’s framing of architectural enclosures presents the prison as a hidden but vital organ of the city.

6 We could draw upon the conceptual arsenal of Foucault’s

Discipline and Punish and Bentham’s panopticon to work out a particular reading of

Marianne and Juliane.

7 But this would leave unaddressed another important element of von Trotta’s feminist imagination. For it isn’t just her shots of penal quarters that frame the film; her interest in the smaller objects of the urban quotidian also guides her narrative. Delineating the fullest dimensions of modern life, von Trotta extends her scope to include both massive prisons and housing blocks, as well as the more ephemeral constructions of the built environment, particularly those of made of textiles. She works within the constraints of the tight shot in her sequences of domestic and carceral confinement and focuses in on the lightweight, mobile structures that furnish and clad these worlds.

Engaging the architecturally inflected cinema studies of Giuliana Bruno, we can develop another analysis of

Marianne and Juliane, one at variance from a Foucauldian critique. Bruno has argued that film is a product of “the metropolitan era,” for it enables a technique of perception that shifts continuously between the interior and the exterior.

8 Her study of Elvira Notari’s early-twentieth-century films maps out a landscape of Naples as it traces the parallels between

flânerie and cinema—their shared juxtapositions of space and time, their privileging of montage.

9 Whereas Notari’s work highlights the flow of men and women through Neapolitan cinemas and arcades, Bruno’s theoretical reflections open up a line of inquiry into von Trotta’s filmmaking.

Marianne and Juliane seeks out the deadlocks of urban planning, its sites of stasis, most specifically those of the prison.

Thomas Elsaesser also offers tools we can use for an analysis of von Trotta’s cinema. In a seminal article on the visual representation of the RAF, he considers the figure of the urban guerrilla in film and television. Although he touches only obliquely on von Trotta, his observations on the dynamics between militancy, media, and surveillance can be brought to bear on the portrayal of public and private space in

Marianne and Juliane. Elsaesser notes that, in the first postwar decades, German society was shaped by the dual forces of its elite culture (that was focused on the theater stage) and its elite government (that was focused on the parliament). Recalling situationist critiques, he observes a turn, since the 1970s, toward the dispersed and disseminated politics of the media spectacle.

10 The RAF’s urban assaults and the postmilitant film that has ensued are prime examples of this turn, for they both reveal how space is activated as a political category.

11 A major determinant of this condition are the technologies of surveillance. German militants, Elsaesser argues, weren’t simply the targets of these urban networks; through their actions they provoked and disclosed the powers of state control.

12 Von Trotta shows this in her film work, as she captures a pivotal moment when these powers began to escalate.

Von Trotta’s attention to the surfaces and structures of authority skillfully conveys the literal and figurative confinement of militants like Meinhof and Ensslin. Yet elements of

Marianne and Juliane cede to the RAF’s own despair, particularly as Meinhof expressed it in her prison notebooks. This compromise exposes flaws in von Trotta’s historical vision. In the following section I will demonstrate how von Trotta blends certain surfaces of the film—walls and windows—into a homogenous screen that doesn’t adequately differentiate the events of the German Autumn from the deeper traumas of fascism. Making Stammheim into a metonym of German authoritarianism, the director, like her heroines, blurs the margins between police state and nation-state. More than this, she also risks equating the RAF prisoners with Holocaust victims.

Marianne and Juliane opens itself up to such scrutiny through its ambiguous incorporation of sequences from Alain Resnais’s

Nuit et brouillard (

Night and Fog, released in 1955 and first broadcast on French television in 1959), one of the first films to document the architecture of the Auschwitz and Majdanek concentration camps. And yet despite this flaw, von Trotta’s observation of the smaller objects of the built environment ultimately resists such a totalizing account. Her film is unique within postmilitant culture, for it situates the German Autumn in a broader context, one that links different moments in the nation’s politics and culture by showing historical continuities in architecture and design.

Controlled Space

Incarceration at Stammheim both shaped the RAF identity and brought about the group’s demise. The prison’s deployment of restraints and the Brandt and Schmidt government’s restrictions of constitutional rights confirmed the RAF’s belief that the FRG was an authoritarian state, thus fueling their militant commitment. The architecture and technologies of the German penal system provided the foundation upon which the Far Left took full form. By the mid-1970s, the RAF and the government had locked into a relationship in which each agent’s action was matched with a reaction from the other side. Armed struggle invited martial clampdown, which then provoked the RAF’s death games of 1977. In September of that year, two days After RAF operatives had taken Hanns-Martin Schleyer hostage, the government banned contact between the seventy-two political prisoners of German jails (many of whom were RAF associates) and all visitors, including their attorneys. Overriding the critics who doubted the validity of this intervention, the Bundestag passed the Contact Ban Law (

Kontaktsperregesetz), which legalized the isolation of public enemies during a state of emergency. This law, still in place today, had a potent effect.

13 The desperate acts of the German Autumn seem to have been the natural end point of the RAF’s reckless trajectory, yet many have argued that the federal ruling made the group’s caustic explosion all but inevitable.

If, in their first years of engagement, militants like Meinhof and Ensslin sought to address social inequality and imperialism, the RAF’s subsequent campaign to exonerate the Stammheim inmates introverted the group’s energies. Meinhof was one of the first to see Stammheim as an example of the repression of German administered society. In her words, “[the] anti-imperialist struggle is fundamentally about liberating prisoners—freeing them from the prison that the system has always been for the people who are exploited and oppressed[,] from the imprisonment of total alienation and self-estrangement.”

14 Although Meinhof never fully substantiated this comparison, the RAF’s broader allegations of abuse at Stammheim can’t be entirely discounted. As their advocates initially attested, and as some historians have since affirmed, wardens were authorized to use unconventional means—including the confiscation of clocks and watches, bodily restraints, and feeding by intubation—to control the militants. Skeptics, meanwhile, have detailed the unusual privileges accorded to RAF inmates, such as the right to speak with one another within the prison and to accumulate large collections of books and recordings in their cells.

15 Indeed, if Baader, Ensslin, and Raspe actually committed suicide at Stammheim in 1977, they probably relied on several modes of communication to seal their pact, some of which their visiting attorneys could have enabled.

16Marianne and Juliane dramatizes the circumstances of the RAF’s imprisonment, activating questions about human rights and criminal justice. Von Trotta accentuates continuities that connect institutions like Stammheim with the postwar order that was developing in the FRG. She underscores other associations as well, such as those that link personal choices with political tendencies, particularly within the field of vision. Tracing the limits between the internal and the external, the public and the private, Marianne and Juliane situates itself at the political intersection of two discourses: the cinematic and the architectural.

The RAF operated within emphatically urban conditions. What becomes evident in the proliferation of the group’s documents as well as the subsequent accounts of the group’s history is that the cityscape was both the medium and the material support of the German armed struggle. The structures of buildings, traffic medians, and underpasses generated the syntax of the RAF idiom. Although

Marianne and Juliane was shot mostly in and around Berlin, parts of the production also took place in suburban parts of the Federal Republic and the former Czechoslovakia, as well as several locations in Italy and Tunisia. But

Marianne and Juliane strays far from the genre of metropolitan

Überblick. While von Trotta tracks broad swaths of the urban condition, she also directs our gaze inward to the private lives lived within the ever smaller precincts of both domestic and penitentiary space. Cinema scholars were quick to emphasize the “personal-is-the-political” premise that informs von Trotta’s feminist aesthetic, but a finer detail of

Marianne and Juliane—the movement across the threshold of the public and private spheres—is what generates the film’s narrative. Focusing on this, we can bring the critique to a deeper level.

17Framing a Narrative

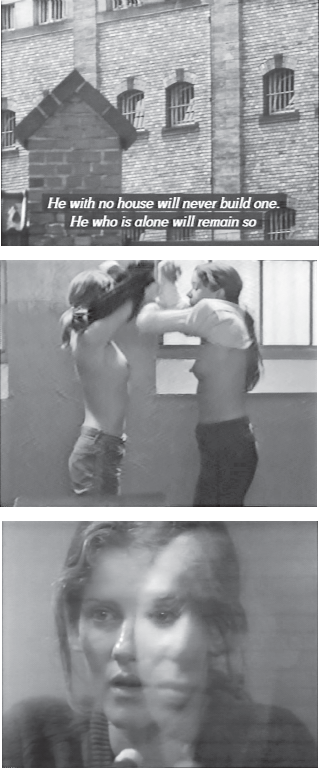

Von Trotta’s repeated focus on windows—particularly barred windows—reminds the viewer of the control systems that define both the public sphere and much of urban life. The film’s first shot is framed through a mullioned window in Juliane’s study that gives onto the bleak interior courtyard of her apartment block. Von Trotta returns again and again to this perspective, using parallel shots of other windows—generic school windows, prison windows girded with metal grillwork—to lend a consistent vision to the film as a whole. The recurrence of these shots both reinscribes von Trotta’s elaboration of the personal/political duality and registers key aspects of the relationship between Marianne and Juliane, the two protagonists.

When Juliane first visits her sister in prison, one shot shows her looking out of a waiting-room window. The window is made of opaque glass, but Juliane finds a small, translucent spot to look through. She leans close and peers into the vacant prison courtyard; all that she can see are brick walls and barred windows. As the camera pans, the shot segues into a view of another residential courtyard, this time that of the sisters’ childhood home, circa 1947. These early years are recalled without nostalgia. The girls’ father, portrayed as harsh and authoritarian, dominates the sequences. With this scenic progression, von Trotta suggests a spatial continuum between prison architecture and the conditions of the traditional German home. She also establishes a temporal link between the 1970s and another related period: the “leaden years” of the 1950s, when Germans found themselves stunned among the wreckage of World War II.

A similar sequential pattern structures another flashback in the film, reiterating the architectural motifs that subtend the story. Here von Trotta doesn’t use dissolves or fades, but rather makes hard cuts to move from time to time and from place to place. When Juliane comes back for another prison visit, the camera follows her gaze upon the building’s windows, perhaps in search of the one that opens onto Marianne’s cell. This image segues to a shot of yet another brick wall: the exterior of the school where the sisters, together in the same class in 1955, are studying Rilke. Marianne recites Rilke’s poem “Herbsttag” (“Autumn Day”), which Juliane derides as

kitschig, provoking her dismissal from the class. The scene suggests that it was Juliane, the elder of the two, who first scouted out the path toward rebellion. The reading of Rilke’s poem also helps establish the film’s somber tone:

Who doesn’t have a house won’t build one now.

Who is now alone will long remain so,

Will stay up, read, write long letters,

And will walk restlessly along the promenades

When the leaves drift down.

18

One reason, perhaps, why the architectural motifs of Marianne and Juliane register so forcefully today is because they figure so prominently in Gerhard Richter’s October 18, 1977 (1988), the photopainting series that is a central reference in postmilitant art. Consider Erhängte (Hanged), one of the fifteen canvasses. Based on a forensic photograph that was widely publicized in television and mainstream media in the 1970s, the painting shows a blurred image of Gudrun Ensslin’s corpse hanging from a window casement in her cell. Richter emphasizes Ensslin’s hyperextended form, her tilted head, and the grillwork from which her body is suspended.

The deeper meanings of

Marianne and Juliane develop according to the spatial parameters that von Trotta describes in the film. Her study of the German cityscape includes smaller structures, especially articles of clothing—the mobile “architecture” that has been conventionally designed and fabricated by women. Von Trotta shapes several key scenes by staging Marianne’s and Juliane’s clothing; their pullovers and slips serve as links between the sisters’ shared past and their divided present. In the scene of Juliane’s first prison visit, von Trotta gives a detailed account of the security protocols. The camera focuses on Juliane and the female warden, who searches her clothing for weapons and contraband. Juliane doesn’t resist the screening until she is asked to remove her pullover. When told that this is standard procedure, she hesitates, and then lifts the garment up over her head, revealing her naked torso beneath. During their next meeting, Marianne recalls the slips or petticoats (

Leibchen) that the sisters wore as girls: “Do you remember our slips?” she asks. “The ones that closed only from the back? No matter how cross [

Spinnefeind] we were with one another, we’d button each other up.” They recall how the straps of the white, cotton slips were either too long or too short, how the fabric itched. But then Marianne quickly changes the subject, switching to the plight of her jailed comrades.

This recollection of the sisters’ shared past precipitates a brief but explosive quarrel about their political differences. Within a few expository lines, the viewer grasps their conflict. Although both women are fully committed to radical social change, only Juliane has chosen to work “above ground” in the public sphere of civil society, where second-wave feminism was at the time aiming to transform German law and media. She sees Marianne’s decision to join the Far Left as a miscarriage of their generation’s struggle for social justice. At Juliane’s next visit, Marianne relates an extended monologue about her penal isolation and changes the direction of their conversation. Juliane begins to grasp her sister’s militant commitment just as the visit times out. When the sisters embrace, Marianne asks Juliane to give her the pullover she is wearing. They quickly undress and then put on each other’s tops, in a single, fluid movement. Refunctioning the control and exposure that marked Juliane’s first visit—for a moment they face each other with bodies exposed, woolen forms held briefly overhead—the sisters perform the gesture as a defiant double maneuver. Then the guards forcibly separate the women and conduct them to the exits.

Juliane realizes the portent of the exchange in the next scene, when she finds a small note in the pocket of Marianne’s pullover. On it she had written: “Talk to friends. Intellectuals, liberals, important people. They should damn well do something for us this time.” In this sequence and in several scenes that follow, fabric objects continue to serve as both medium and message at once. The news of Marianne’s death, a purported suicide by hanging, devastates Juliane: suffering a nervous collapse, she grieves her sister’s loss and has a fevered dream. In it she recalls, again, the slips and the shared ritual of buttoning them up.

Wall, Dress, Screen

It might seem strange to speak of fabric and clothing as part of the city, but von Trotta’s alertness to the connections between small-scale, mobile structures and the architecture of power has a notable precedent. Indeed,

Marianne and Juliane makes several points of contact with the early modern architectural theses of Gottfried Semper and Adolf Loos. Semper’s study

Der Stil in den technischen und tektonischen Künsten (

Style in the Technical and Tectonic Arts, 1860) locates the crux of architecture in the textile, disclosing the tight knot that binds the fabrication of buildings with the clothing of the human body. In his “Prinzip der Bekleidung” (“Principle of Cladding” or “Principle of Dressing”), Semper extends his analogy between walls and dressing (

Wände and

Gewände) to argue that architecture’s truth consists not in its internal supports, but rather in its covering layer.

19 Taking Semper’s lead, in 1898 Adolf Loos published his own “Prinizip der Bekleidung,” a manifesto that calls for an architecture that emphasizes the “outer layer” building.

20 Even though it dissimulates the structure it covers, this layer of cladding mediates our perception of the building. For Semper, architecture originated with the use of woven fabrics. Textiles—historically a woman’s craft—weren’t simply placed within an enclosure to give a sense of interiority, he argues. Rather, by introducing the idea of dwelling, they enabled the production of space itself.

21 Fabrics thus generate both the house and social structure. The interior isn’t defined by a continuous enclosure of walls, but by the folds and twists in an often discontinuous decorative surface.

Von Trotta’s interest in textiles both recalls Semper and Loos and anticipates the most recent tendencies of design. The staging of objects in

Marianne and Juliane draws our attention to the possibilities of modern and contemporary architecture, such as the tensile construction of Günter Behnisch and Frei Otto’s stadium for the 1972 Olympic Games in Munich. Suspended from steel pylons, the stadium’s perspex tents created a seemingly ethereal contrast to Albert Speer’s colossal arenas for the Berlin games in 1936. Against the fascist ideal of a static

Heimat, this variable architecture participates in a nomadic culture of transit and contestation. What seems mobile or portable in the Munich structure is more fully realized in the “wearable shelters” of several other designers: Peter Cook’s works for the firm Archigram in the 1960s, Hussein Chalayan’s “furniture dresses” of the 1990s, and the armored garments being produced by engineers at the MIT Media Lab today.

22 This sort of clothing outfits the body for duress, subterfuge, and escape. Von Trotta’s mobilization of cloth objects in

Marianne and Juliane approaches the horizons envisioned by these designers. It privileges the portable and mutable; it gestures toward nonstandard and even transgressive designs.

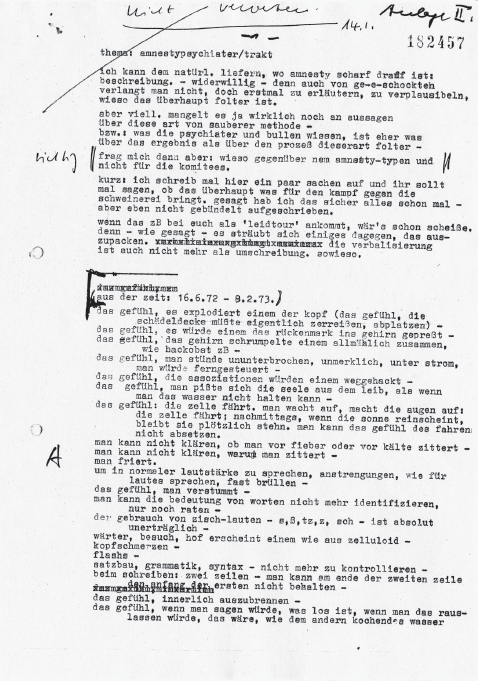

Die bleierne Zeit (Marianne and Juliane), dir. Margarethe von Trotta, 1981. Film stills.

After introducing the slips and pullovers into Marianne and Juliane, von Trotta enters a third material object into the narrative, bringing it to a close. Juliane splits with her partner Wolfgang (an architect) and moves to her own apartment. Although she once resolved not to have children, she finds herself with little choice but to take custody of Marianne’s orphaned son. Then Juliane devotes herself to investigating the cause of her sister’s death, reading books about knot-tying and marking the pages that show nooses. She requisitions the belongings Marianne kept when incarcerated and works out a whole calculus of figures—her sister’s weight, the height of the window grates, the maximum load that it could bear—all in an attempt to assess whether she could have committed suicide from inside her prison cell. Von Trotta films Juliane absorbed in the task of stitching together a life-sized model—Marianne’s body double. A pattern is cut from cloth; each limb is tacked and sewn, filled with sand, and finally assembled into a puppet or dummy. Juliane ties a rope to her own window casement and hangs the dummy from it. The form dangles a few seconds as she looks on in horror, crouched in the corner. Then, suddenly, the cord breaks, letting the dummy drop and corroborating Juliane’s conviction that, since a prison suicide was impossible, Marianne must have been murdered.

Semper’s comparison between

Wände and

Gewände finds its third term in the

Leinwand, or “screen,” of

Marianne and Juliane. Von Trotta emphasizes the structural essence of this cinematic screen in her framing of walls and windows, particularly toward the end of the film, when Marianne is transferred from her quarters in a Wilhelmine-era jail to a modern facility that resembles Stammheim. The sisters have their last visit under the surveillance of armed guards, stenographers, and closed-circuit television. A wall of mesh-reinforced glass separates them, forcing the women to communicate via an intercom system. As Juliane’s voiceover notes, there are no more iron grates on the windows in the modern prison, only blinds and screens. Seated to face each other directly, their individual reflections on the glass obscure the sisters’ view of each other. Von Trotta shows Marianne’s face superimposed onto the reflection of Juliane’s, creating an image like a blurred photomontage. This composite picture connotes the distorted ego boundaries of the two sisters—as Marianne’s prospects for exoneration dim, Juliane’s identification with her grows more desperate. This might be seen to symbolize the relationship of the Stammheim inmates to their outlying supporters in the 1970s, a relationship that merits closer attention.

The Stammheim Complex

Penal architecture gave shape to German militancy. It also left an impression on postmilitant culture, as we see in

Marianne and Juliane. Von Trotta’s staging of the sisters’ final encounter in the prison’s visiting room dramatizes the alienating effects of the federal discipline for many on the Left during the German Autumn. Marianne describes her confinement as disorienting and dehumanizing. Isolated from any sound, constantly exposed to bright light, she loses track of time and, ultimately, all sense of self in the “dead stillness” of her cell. As the Far Left broke off from the more moderate course of the New Left, it also seemed to lose its own temporal bearings and sense of history, much like Marianne does in the film. The RAF, in particular, succumbed to this disorientation and historical amnesia, delusionally imagining that its plight was akin that of Hitler’s victims. Legal advocates who defended Meinhof, Ensslin, and other militants posited an association between Stammheim and the death camps of German fascism. In her prison writings, Meinhof remarked that her understanding of Auschwitz and its effects became clearer while serving her sentence; in her words, the “political conception of the Cologne prison’s dead section … is the gas chamber.”

23 As the journalist Hans Kundnani writes, RAF inmates referred to Stammheim’s conditions as

Sonderbehandlung, or “special treatment,” the Nazi euphemism to describe Jewish genocide.

Vernichtungshaft, or “extermination incarceration,” was another term used by the RAF.

24 The New Left might have suspected that fascist tendencies persisted in the postwar period. The RAF, meanwhile, was utterly convinced that the Third Reich’s structures of domination extended into the foundations of the Federal Republic.

Meinhof and Ensslin made frequent reference to the design of Stammheim in their writings. Paradoxically, the building’s physical restraints worked to amplify the militants’ communiqués. Kept under close watch, the RAF inmates reoriented their critique and recoded the terms of their agenda according to the constraints of incarceration. Transcripts of their depositions record the RAF’s shift in strategy from an active, international struggle to an interiorized politics of discontent. Under the sway of what we could call a social or psychological Stammheim Complex, Meinhof and Ensslin saw the prison as a symbol or microcosm of the police state—its architecture of repression, its systems of surveillance. If the penal institutions served as a theater of state violence, the RAF could incite revolt from within the walls of Stammheim. The inmates’ resistance was pitched to spark a revolution that would overtake the country and then spread into the international domain.

In the mid-1970s, as the RAF’s outlook contracted to Stammheim’s pinpoint perspective, Meinhof and Ensslin tried to subsume the complicated array of social, political, and economic conflicts into their own singular predicament. They worked out a reactionary rationale that united the destinies of the RAF and other oppositional movements and projected illusory bonds of solidarity and shared purpose. Despair magnified this distortion, blinding the RAF to the actuality of its situation: protracted confinement had ruptured most of the group’s external affiliations and stunted its powers. In effect, the militants had switched from open revolt to the institutionalized revolution that Julia Kristeva has theorized.

25 Ceasing to question themselves, the first generation lost hold of any real transformative power. The RAF was becoming an empty signifier lacking any referent to the transformations taking place outside the prison complex, whether within West Germany’s new social movements or elsewhere. Underscoring their victim status, the Far Left sought to legitimize the violent tactics of the armed struggle.

26Marianne and Juliane skews its spatial and temporal coordinates, replicating some of the historical misrepresentations that were symptomatic of RAF’s Stammheim Complex. The film’s interlinked sequences from 1947, 1955, 1968, 1977, and the last years of the 1970s fix our focus on the concentration camp as the defining historical moment of German modernity. The continuity that von Trotta establishes between the German home and the German prison recurs in her portrayal of the associations between different historical periods.

Marianne and Juliane maintains an intertextual relationship to Resnais’s

Night and Fog, particularly the final segment depicting Auschwitz and Majdanek After liberation.

27 Indeed, von Trotta’s investigation of Marianne’s enigmatic death echoes Hitler’s order, mentioned in the film, that arrested members of the resistance be made to disappear “in the fog of the night” (

Nacht und Nebel), such that their deaths wouldn’t be divulged. The narrator in Resnais’s film describes the concentration camp as “an abandoned town” set into a landscape “pregnant with death.” The deadlocks of

Marianne and Juliane are repeatedly projected over this same terrain, a place from which, von Trotta implies, no German can escape.

In her efforts to illuminate the correspondences between domestic, penitentiary, and concentrationary space, von Trotta risks setting all of German modernity under the sign of the Holocaust and depleting other moments of their historical specificity. The indeterminate incorporation of

Night and Fog prompts a crucial question: might

Marianne and Juliane invite viewers to falsely identify with the victims of German fascism—the Jews, above all, but also communists, Slavs, and other targets of the Nazi siege?

28 Ceding to the impulses that guided Meinhof’s and Ensslin’s declarations, von Trotta nearly elides Stammheim with Auschwitz.

The German Autumn reopened the wounds of the fascist past and forced many to confront difficult questions about individual and collective responsibility for mass violence. This belated encounter unlocked the process of ethical reckoning for some, but it also disclosed a range of flawed perspectives. Marianne and Juliane ventures a parallel between the victims of the Holocaust and the Far Left, falsely framing them as linked objects of fascist and neofascist domination. Yet the film steers clear of a broader tendency in the national media and popular culture. While the Stammheim trials became a platform for the RAF’s phantasmatic identification with the victims of the Nazi state, other judicial proceedings that were unfolding in the 1970s contributed to a broader pattern of public disavowal.

The Stammheim trials began in 1975, the same year that the Dusseldorf tribunal for war crimes at Majdanek. The two trials were conducted according to different legal codes, and they were covered differently in the popular press. These differences provide an important context for understanding the circumstances surrounding the realization of

Marianne and Juliane.

29 As was the case in other war crimes tribunals conducted in Germany, the Majdanek defendants were tried according to the Nazi laws that existed during the years of their actions. The use of these codes enabled the defense to significantly mitigate the sentences. Although the former Majdanek guards were charged with up to seven thousand murders each, most were acquitted. In the Stammheim hearings, meanwhile, Meinhof, Ensslin, and the other RAF leaders were judged by the far more rigorous guidelines that had been established in the new constitution of 1949. Over and against the genocide trials, in the 1970s the federal courts framed the RAF as Germany’s most dangerous enemy.

Presented in this way, the Stammheim cases dominated the media for years. Newspapers and networks gave relatively little coverage to the Majdanek proceedings, despite the fact that they ran until 1981, the year Marianne and Juliane was released. Editors and broadcasters chose, instead, to keep the Far Left in the headlines. Hundreds of witnesses and survivors from across Europe came to Dusseldorf to testify about the (estimated) 250,000 deaths in the Majdanek camp, but the public seemed to take a much greater interest in the Stammheim hearings. Journalists wrote detailed accounts of the RAF’s situation, describing their renegade lives in the terrorist underground and documenting their deprivations while behind bars.

Meanwhile, the Majdanek findings seemed to fall on deaf ears. More than a common desire to let the past fade into oblivion, the favoring of the Stammheim story over the Majdanek tribunal facilitated a treacherous recasting of guilt and complicity. By the late 1970s, the RAF had perpetrated about half of the thirty-four fatal attacks they would ultimately commit, a death toll that is a tiny fraction of the millions who were killed in the Holocaust. But the focus on Stammheim elevated the targets of RAF terrorism into dominant symbols. As if to disregard the history of Majdanek or other acts of German genocide, many construed the entire postwar nation as victims of leftist violence.

If

Marianne and Juliane points to the problems of representing and confronting rogue and state terror, von Trotta’s feminist vision nonetheless offers an uncommon perspective on the significance of the German Autumn within the postwar period. Her investigation of the margins between the personal and the political, evident both in her treatment of the architecture of public and private spaces and in her depiction of the sisters’ relationship, lays a foundation for discussing the shifting sites of truth and power within German democracy. In an attempt to wipe out leftist militancy, policymakers instituted a series of controls on both political dissidence and its legal defense.

30 This legislation placed the first restrictions on constitutional rights since the founding of the FRG. The Stammheim trials also extended the state’s incursion into the private life of the individual. When RAF inmates held hunger strikes and refused to attend their own hearings, authorities compelled them to force-feedings and, in several instances, prosecutors conducted the trials in the defendants’ absence. As Jeremy Varon has argued, these actions conveyed the state’s imperative that there be no space “outside-the-law.” Thus Stammheim became a “space of total confinement” that reinforced the state’s “monologic authority.”

31The injunctions of the Stammheim court made it difficult to dismiss a central message of Marianne and Juliane: that Germans remained in a concentrationary universe decades After the liberation of the death camps. But Varon’s account can also enable a new critique of the film. Von Trotta leaves open the question of Marianne’s murder under the wardens’ watch; when the film was released, conclusions hadn’t been drawn about the cause of the Stammheim deaths in October 1977. The subsequent consensus that the RAF inmates committed suicide gives new meaning to von Trotta’s investigation of the public/private divide in postwar German society. Meinhof’s and Ensslin’s decisions to take their own lives might be seen as an attempt to claim autonomy from the state power that was driven to annihilate them. Committing suicide, they used their bodies to delimit a discursive “outside” to prison law. But what a high price to pay.

Modes of Redress

Already in the 1970s, critics doubted the agency of the Far Left, whether inside Stammheim or at large. In 1975

Spiegel editors prepared a set of pointed questions for Meinhof, Ensslin, and the other inmates; they asked about the perception that the RAF lacked “an influence on the masses” and had no “connection to a base.” The militants offered a telling reply. Within the FRG, they noted, there endured only a “trace of RAF politics.”

32 Their response acknowledges a degree of defeat, but we can also take it toward a new line of inquiry. Where did the RAF’s political “trace” appear when Meinhof and Ensslin sat for years in solitary confinement, or when they were at the hour of their death? Where has it become manifest in the decades that have followed? The incarceration of the Far Left’s top cadre channeled their energies into a series of hopeless ultimatums. After armed struggle, first came implosion and then a general malaise that emptied out the RAF’s larger objectives.

In its production and at its release, Marianne and Juliane carried vestiges of Meinhof’s and Ensslin’s lives, the compromises and choices they made—particularly as women—to resist state domination with guerrilla violence. Viewed today, the film is an example of the continuing difficulty of accounting for militancy. Yet von Trotta’s reflections on spatial politics nevertheless make a feminist intervention at the levels of the political as well as the aesthetic. They capture the complex temper of the late 1970s, a time when women sought to counter political melancholy, reclaiming their bodies and transforming German society through all available means, from margin to center. Marianne and Juliane conveys the dynamics of collaboration and dissonance among women that charged this moment.

To Giuliana Bruno’s modernist insight that “film spectatorship incarnates the metropolitan body,” von Trotta might counter that penal complexes and the techniques of visual surveillance function to control it, to still it.

33 But, in a minor key,

Marianne and Juliane also grants us purchase on the transgressive potentials that inhere in the built environment. The sisters’ subversive play with fabric objects contravenes the dictates of the police state. Their acts also gesture toward a new mode of design, where variably fashioned structures might enable autonomous challenges to tradition and state authority.

Some have asserted that the most enduring effect of the German Autumn has been the divestment of constitutional rights and the entrenchment of federal power. Indeed, revolutionary violence could only accelerate this counterdemocratic tendency. And yet

Marianne and Juliane, perhaps despite von Trotta’s intentions, indicates that the state’s grip isn’t so total, After all. More than a generation After 1977, her film still attracts a wide audience.

34 It engages cinematic means to promote critiques of both government repression and political violence. If

Marianne and Juliane discloses the structures and systems that control targets of suspicion, it also shows us how the targets might return that gaze, in other words, how the object might look back. As Marianne contends from inside the prison walls, the authorities will always have to vie with autonomous forces: “They’ll never pull us down from the windows,” she claims, “because they have no power over our souls.”

35 The idealism and romance of these lines stem out of the militancy of the German Far Left and extend into a broad field of postmilitant culture. As we shall see in the next chapter, von Trotta’s attempt to align German history with the systemic oppression of women also set a precarious precedent for the next wave of culture that sought to make sense of postwar militancy and terrorism. The matters of autonomy and victimization that von Trotta explored would become increasingly difficult for artists and writers in the 1980s, especially when they were laid over the uneven terrain of gender politics.