In an

Artforum review in 1997, the historian Anders Stephanson speculated that “hijacking may continue, but its historical moment (in a Hegelian sense) is over.”

1 Written twenty years After the German Autumn and almost ten years After one of the last massive terrorist attacks—the Libyan bombing of Pan Am Flight 103 over Lockerbie, Scotland—the review discussed

Dial History (1997), Johan Grimonprez’s film about air traffic, militancy, and death. When

Dial History became the hit of documenta X, the international exhibition of contemporary art held in Kassel, Germany, the tempest of transnational terrorism and its attendant media surge seemed, to many, to have died down.

2 Grimonprez’s film set a series of airplane hijackings to a disco beat and imparted a saturated glare to the screen, as if to consign to the outmoded databanks of the 1970s not only the terrorist acts of the RAF and other Far Left groups, but the progress of history itself. It pieced together film clips of the Landshut hijacking with footage of strikes and demonstrations around the world. As half a million documenta visitors flocked to the Fridericianum Museum to see the film, aeroterrorism lulled. But

Dial History and its audience were only resting in the eye of the storm, for the events of September 11, 2001, were nearing the horizon. When al-Qaeda planes crashed into the World Trade Center, and when security systems everywhere went up to code red, Germans were reminded of their own legacy of political violence. On the culture front, a sonic boom in postmilitant art would soon follow.

In 2005

Dial History played to its second large audience, this time as part of

Zur Vorstellung des Terrors: Die RAF (

Regarding Terror: The RAF), the popular and controversial exhibition that was held at the Kunst-Werke Institute for Contemporary Art in Berlin. Here Grimonprez’s film was shown to be just one example of the scores of artworks that have responded to leftist militancy and terrorism.

Regarding Terror was a milestone in postmilitant culture, as it set out to measure, for the first time, the profound and lasting artistic response to the German armed struggle. At that point many well-known artists had made work about the RAF (for example, Joseph Beuys, Martin Kippenberger, and Gerhard Richter), and a sort of Baader-Meinhof “culture industry” had been exported to other European countries and the United States, but no show on the topic had been curated, no survey published.

3 If Grimonprez had created a stir at documenta X, news of the American air war seemed to touch a nerve for many Germans. Within months of September 11, the Kunst-Werke curators began to prepare the RAF exhibition.

In 2002, when word of the show first got around, it ignited a media blitz that covered Mohamed Atta’s Hamburg-based cell of Islamic radicalism, the growth of the RAF in Germany, and the state’s backlash against it. This reportage factored into the curators’ conception of the exhibition. As they reviewed the artworks that mobilized pictures of the Far Left, the Kunst-Werke team realized that, in many cases, the artists weren’t just looking at the RAF; they were looking at the way the media looked at the RAF. Their paintings, installations, and films recalled and reproduced news images that had circulated for decades. Foregrounding the role of the media in the cultural response to revolutionary violence, the exhibition promised to offer a unique perspective on art and political extremism in the public sphere. The curators were fully aware that the RAF itself had contended with national news networks from the beginning to its end.

4 Conservative conglomerates like Axel Springer AG had been a prime target for militants. Ulrike Meinhof, for example, had used her status as a journalist and commentator for radio and television as a tool for subversion. And in 1998 the RAF had enacted its dissolution by issuing a final communiqué to the Reuters Agency. The choice of media as a framing device for the Kunst-Werke exhibition was thus well considered.

5The problem with

Regarding Terror was that the emphasis on the media’s role eclipsed the questions of why so many visual artists have fixated on the RAF’s actions, how the artists have handled and transformed documentary material, and what we can learn from this aesthetic formation. The layout of the show, the production of its catalogue, and the programming of related events such as press conferences and public lectures combined to disinterestedly survey postmilitant culture, but not to analyze it in any substantive way. However, certain artworks within the exhibition did activate this kind of investigation on their own terms. These works ask about the potential for visual art to compete with documentary and mass media images that, today, are culturally dominant.

6 They also take up the RAF image and turn it into a prism that refracts a range of concerns, including Germany’s history of violence and the access to power in late modernity. In order to articulate this investigation, in this chapter I focus on the work of four artists included in

Regarding Terror: Johan Grimonprez, Hans-Peter Feldmann, Gerhard Richter, and Yvonne Rainer. Considering them together, we further our investigation of the margins between art and terror, aesthetics and politics.

Curating the Urban Guerrilla

Klaus Biesenbach, the founder and former artistic director of the Kunst-Werke, first conceived the exhibition under the rubric “Mythos RAF”—“The Myth of the Red Army Faction.” Collaborating with a team of young curators that included Ellen Blumenstein and Felix Ensslin, Biesenbach drew up a list of the extant artworks that referenced the RAF—they knew of nearly one hundred—and began to contact mostly left-leaning critics and historians, asking them to contribute texts to the project. Biesenbach’s team also held a series of press conferences and applied for government funding, both of which quickly brought the Kunst-Werke into the harsh light of public criticism. By early 2003, most of the major German newspapers had reported on the curators’ plans for the show. Families of Jürgen Ponto and Alfred Herrhausen, two prominent figures killed by the RAF, made their objections plain, lobbying their local representatives to block a project that would risk idealizing militancy and terror.

7When the Berlin Senate began to deliberate the Kunst-Werke’s funding application, Biesenbach changed course.

8 Preempting a possible denial of subsidies, he withdrew his proposal and raised private resources for the exhibition by auctioning works donated by Andreas Gursky, Thomas Demand, and other notable artists.

9 The institute also changed the exhibition’s title from “Mythos RAF” to

Regarding Terror, a choice that suggested a more cautious approach to the topic. Although many artists agreed to participate in the show, the original plans to manage the project started to fall apart. Gerhard Richter refused the inclusion of

October 18, 1977, offering instead to lend several elements of another work keyed into the theme.

10 The historian Wolfgang Kraushaar provided a text for the exhibition catalogue, but then publicly denounced the show.

11 Jan Philipp Reemtsma, the director of the Hamburg Institute for Social Research, which maintains the largest archives on the RAF and other protest movements, had planned to contribute an essay, but he broke ties with the Kunst-Werke and gave lectures that criticized the curators’ role in glamorizing and distorting the history of the Far Left.

12In the process that led up to Regarding Terror, the Kunst-Werke team faced the close scrutiny usually reserved for curators of major international exhibitions such as documenta and the Venice Biennial. The stakes were high: since no other museum had directly addressed the RAF story, Biesenbach’s proposal drew attention far beyond the art world. Skepticism prevailed at every stage. Were Germans ready to reopen the wounds of the German Autumn? Could artists give an ethical—or even adequate—response to this chapter of history?

As if to deflect this criticism, the curators chose to organize

Regarding Terror according to the principle of historical chronology. They devised a media time line that documented events in RAF history from the late 1960s to the group’s dissolution in 1998. The information presented in the chronology was drawn from articles in five national newspapers and magazines:

Bild,

Der Spiegel,

Stern, the

Frankfurter Allgemeine Zeitung, and the

Süddeutsche Zeitung, some of the same outlets that the Far Left had contended with in the 1960s and 1970s. The didactic time line was mounted on large panels that encircled the Kunst-Werke’s main gallery. Below the panels were television monitors that rolled period tapes produced by national and international broadcasters. Many museum visitors took the opportunity to put on headphones, watch the screens, and read the wall text. Centered within the time line and anchoring the main gallery was Hans-Peter Feldmann’s artwork

Die Toten (

The Dead, 1988), a series of chronologically ordered images of all the people who died as a result of RAF violence. The linear sequence of the items in the main gallery was further reinforced by the exhibition catalogue. The first and largest of its two volumes consists of facsimiles of German print journalism, ordered by date. The hundreds of articles collated in the book testify to the sustained media interest in the Far Left over the course of three decades.

While preparing the exhibition, Felix Ensslin noted that the RAF story had been repeatedly “written and rewritten” by reporters and historians.

13 The time had come, he noted, to show how visual artists had responded to the RAF and to confront the viewers with the “objects” they had produced.

14 In its display, however,

Regarding Terror mainly reiterated standard historical accounts of the German Autumn and rehashed the common observation that the armed struggle had drawn a huge amount of media attention. Analysis of the specific art objects and inquiry into their modes of resistance were left by the wayside. Further, the central position of the Kunst-Werke’s time line and Feldmann’s

The Dead in the main gallery overshadowed other, more complex artworks included elsewhere in the exhibition. This effect can be discerned most clearly by comparing

The Dead to the works of Grimonprez, Richter, and Rainer, which were installed on the museum’s upper floors. Each of these three projects recalls the chronology of the RAF years, but the artists use aesthetic means to offer counterhistorical perspectives on political violence and state security.

In “The Cultural Logic of the Late Capitalist Museum” (1990) the art historian Rosalind Krauss notes a growing tendency for sensational museum events, such as the hiring of star architects to build new galleries and the staging of hit shows, to impede the viewer’s personal encounter with the individual artworks contained within a given exhibition.

15 To a great extent the Kunst-Werke curators enacted this kind of public spectacle. This chapter takes its cue from Krauss’s article and goes beneath the surface of

Regarding Terror. It elaborates a comparison of works by Feldmann, Richter, Grimonprez, and Rainer, setting them first into the curators’ narrative and then reading them against the cultural logic of the Kunst-Werke time line. What we find are a range of temporal and compositional strategies that, to varying extents, work against the museum’s chronological standard to posit alternative spaces for reflection and critique. Rainer’s early film

Journeys from Berlin/1971, made in 1977–78, is particularly notable in this regard, for it deploys strategies that plot out a “counterpublic sphere,” one that is distinctively feminist.

RAF Chronologies: Feldmann and Richter

Since the mid-1970s, articles and books, documentary films, and websites have recounted the Far Left’s march through history and the state’s response. The media time line in Regarding Terror was only one instance of this routine in compulsive documentation. Many artists in the exhibition used news items as a point of departure in their work. But their handling of media chronology differs: while Feldmann replicates its linearity, Richter, Grimonprez, and Rainer variously denaturalize and undermine the notions of resolution and progress that are seen to inhere in standard accounts of the RAF. As we shall see, their work aligns with some of Adorno’s thought on dialectics, history, and time.

Feldmann’s

The Dead operates primarily as a conceptual project.

16 Adhering to strict formal principles of format and order, it is essentially a chronology in pictures. To create the series, Feldmann found press photographs related to each of the ninety casualties that resulted from German terrorism and counterterrorism.

17 He selected pictures of unusual intensity. Schleyer held hostage under the RAF emblem. Meinhof in a prison courtyard, giving a look that could kill. A forensic shot of Baader with blood pooled around his head. Each death is marked by a single image, untouched, but cropped to a uniform size. Feldmann photocopied the pictures in black and white onto 30 × 40 cm sheets of paper and captioned each page with the name of the individual and the date he or she died. The sheets are ordered by date, beginning with the student activist Benno Ohnesorg (†June 2, 1967) and ending with RAF member Wolfgang Grams (†June 27, 1993).

18 Between these two end points, the time line is punctuated by the deaths of victims and perpetrators alike. The standardization of the sequence cancels out the attributes that distinguished agents from targets, factoring suicides and killings into a single death toll. Ordered in this way, the images of

The Dead show the viewer a temporal progression that glides over historical antagonisms. Ideological and political differences are leveled. Many critics of the Kunst-Werke show disparaged Feldmann’s series, perceiving in it an implication that the armed struggle was a civil war, that its soldiers should be mourned equally, that death erased the distinctions of the fallen.

Gerhard Richter, in his reflections upon leftist militancy and the state’s reaction to it, has played against the discursive order prescribed by official accounts of the RAF.

Atlas (begun in 1962 and continuing to the present), his massive archive of images, is an ongoing study, begun in 1962, of the ways that photography registers a range of social conditions. Among other things, it indexes the “anomie, amnesia, and repression” that Benjamin Buchloh has identified as features of postwar Germany.

19 Atlas has an irregular temporal structure that challenges the strict chronology of works like

The Dead. Playing with time, Richter opens up his project to a number of compelling contradictions. He also opens up a line for postmilitant criticism. As Buchloh argues,

Atlas functions as a critique of “photography as a system of ideological domination,” a system, I would add, that enforces the ordering of time and space.

20 The subjects Richter includes range widely, from everyday snapshots, to self-portraits, to official documents of major historical events. Ten individual sections of

Atlas (identified by the Richter studio as sheets 470–79) were exhibited in

Regarding Terror. Retitled

Baader-Meinhof Photographs for the show, the Richter sheets allow for productive comparison with

The Dead.

Gerhard Richter, Atlas Tafel 432 (Atlas Sheet 432), 1989. Black and white photograph reproductions.

The ten sheets were rigorously produced: each one is the same size, and each displays eight or twelve black-and-white photo reproductions, also of equal dimension. In total, one hundred pictures appear on the sheets. But Richter upsets this formal balance with a number of tactics. Intentionally blurred, the pictures were made by reshooting press photographs from a large collection that Richter used as resource material for the photopaintings in

October 18, 1977. Images that recall

Festnahme (

Arrest),

Gegenüberstellung (

Confrontation), and

Zelle (

Cell) are readily identifiable to viewers who know Richter’s work; however, the artist chose to exclude the original photographs that he relied on to produce the

October 18 canvasses. A group of other pictures that Richter collected while working on the RAF paintings in the 1980s provides a critical supplement to the ten sheets: several Baader portraits (again, still blurred), familiar photos from the Stammheim trials, and a seemingly random picture of a man holding an infant. Taken together, they are a record of the artist’s comprehensive research process, a record, in fact, of his life.

The

Atlas sheets are dated 1989, which is the year that followed Richter’s completion of

October 18, 1977. Richter’s decision to situate the photographs

posterior to the paintings created a temporal wrinkle that motivates the viewer to consider the effects of standard chronology on our understanding of the RAF. Other instances of untimely sequencing in

Atlas suggest that Richter is exploring the larger relationships between lived history, collective memory, and the media. However the Kunst-Werke curators’ treatment of the

Baader-Meinhof Photographs in

Regarding Terror made it difficult to appreciate this aspect of Richter’s practice.

21 Indeed the curators’ (temporary) removal of the ten sheets from the rest of

Atlas elided the important correspondences between the RAF photos and other formal, historical, and pictorial themes that Richter develops in his larger project. Particularly striking are the associations between the

Baader-Meinhof Photographs and certain key elements of

Atlas, for example, sheets 16–20, which depict concentration camp prisoners, and sheets 21–23, which depict women posing in pornographic scenarios. A number of other sequences interspersed throughout

Atlas incorporate photographs of Richter and his family members, including his wives, his children, and an uncle who was an SS officer. Integrated within

Atlas, the RAF photos open channels of inquiry into several interrelated topics, such as ideological contestation, crimes against humanity, and the status of women. They also place the German armed struggle into a much broader context, mapping its movement out from the sphere of the external and public and into the domain of the internal and private. The manner in which the Kunst-Werke curators exhibited the

Baader-Meinhof Photographs could do no more than repeat the organizing principle of

Regarding Terror: the RAF was best accounted for in accordance with a linear sequence, a chronology proving that something had been overcome and resolved.

How to compare Feldmann’s The Dead to Richter’s ten Atlas sheets? How does each work relate to the concept of postmilitancy? Like the Kunst-Werke’s media time line, The Dead aims for documentary objectivity. It tabulates empirical evidence and orders it accurately, but even as Feldmann holds out the possibility of “total recall” about the German armed struggle, this very totality connotes the amnesia and anomie that Richter has challenged. Other problems are apparent in Atlas sheets 470–79. Like October 18, 1977, these images blur the distinctions between document and memory, but they also risk obliterating certain casualties of RAF terrorism. Richter shows only Meinhof, Ensslin, and Baader, not Schleyer, Ponto, or any other victims targeted by the group. Viewed in relation to the concentration camp photographs in Atlas, these pictures also risk implying that members of the RAF were victims of the German state, and not criminal actors in a complex arena of politics. Certainly, Richter is not going for the objectivity of Feldmann or the Kunst-Werke curators. With his counterhistorical tactics and incorporation of personal material into Atlas, he doesn’t seek to “cover” or “master” the story of the RAF. By integrating the Baader-Meinhof Photographs into the corpus of Atlas, he shows how even the extreme actions of militancy and terrorism are integral to German self-understanding. Seeing sheets 470–79 within Atlas, we sense the critical leverage of postmilitancy; the pictures that figure there function within the larger work of art to heighten the tension between the aesthetic and the political. Taken out of context, however, the pictures lose this acuity. Like The Dead, the Baader-Meinhof Photographs, as selected by the Kunst-Werke curators, operated primarily as temporal markers in Regarding Terror. The curators conveyed the information that the German armed struggle had taken place and had been surmounted, but they stopped short of analyzing the persistent effect of the RAF on the many lives that carried on in its Aftermath. Turning to works by Johan Grimonprez and then to Yvonne Rainer, we’ll see other examples of postmilitant practice in which aesthetic means are used to move beyond the impasse of Regarding Terror.

History, Counterhistory: Grimonprez

At a Kunst-Werke press conference in January 2005, a reporter asked about the goals of

Regarding Terror. “This show isn’t about the RAF,” Biesenbach responded, explaining that the initiative was rather “about reflections of the RAF in newspapers, magazines, and then in the art works.”

22 Biesenbach’s introductory essay to the exhibition catalogue reinforces this point. The media, he argues, has “uncoupled” images of the RAF from their historical contexts, “alienating and mythologizing” them.

23 The art included in the Kunst-Werke exhibition, according to Biesenbach, countered this “displacement and repression” of “the real world” with “the precise, slow, focused use of images.”

24 But in fact the curators repeated this kind of uncoupling when they removed Richter’s

Baader-Meinhof Photographs from the framework of

Atlas and repackaged them for convenient consumption. Grimonprez, in

Dial History, did something similar. He spliced together disparate clips to produce a film that becomes precariously entertaining. Yet certain compositional choices distinguish Grimonprez’s work from the Kunst-Werke logic.

Dial History is a panorama of aeroterrorism from 1931 to 1996. Edited with a quick pulse and accompanied by the dance track “The Hustle” from 1975, the jump cuts of this sixty-seven-minute film operate in opposition to the “slow, focused” reflection that Biesenbach emphasized in his essay. Like Richter’s

Atlas,

Dial History signals a resistance to standard chronologies, as it uses interruptions and interjections to show the limits of such conventions in representing historical contradictions.

25 In addition to this temporal manipulation, Grimonprez contrasts multiple sources in

Dial History—raw documents of airplane hijackings and popular demonstrations, random television advertisements, and a number of literary references. He also directs our gaze toward the victims of terrorism. An extended interlude shows a woman on a Tokyo runway searching for a loved one among the survivors of a hijack. Another sequence excerpts B-roll footage of a worker mopping up blood After a lethal strike at an airport gate. Interspersed among the various images are scenes that have marked the development of modern ideological fundamentalisms: Soviet masses gathering to see Lenin, flag-waving ranks of the Red Guard marching across Beijing, enraged mourners at Khomeini’s funeral in Teheran. The flashbacks and montages provide a cinematic response to Don DeLillo’s novels

White Noise (1984) and

Mao II (1991), which Grimonprez cites at length. This literary interplay gives

Dial History an unusual texture, leading us away from the visual spectacle of hijacking to search for some deeper meaning between the frames. With its peculiar syncopation, Grimonprez’s film is pitched to enter into the viewer’s mind and turn it into a “construction site,” as Alexander Kluge has put it. Like

Germany in Autumn, which Kluge helped direct and produce,

Dial History invites our active involvement.

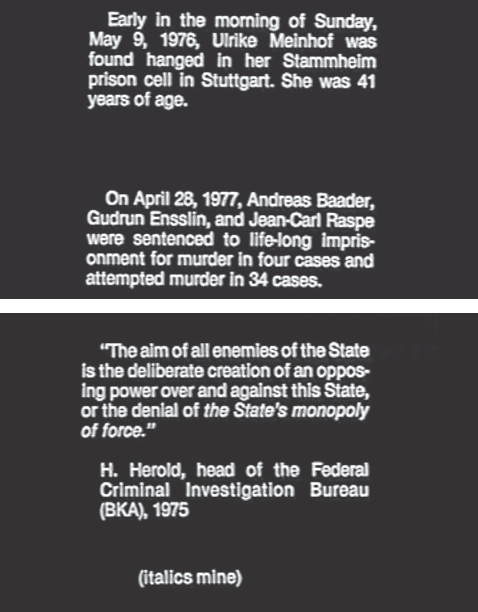

About two-thirds of the way through the film, Grimonprez shows a series of clips that document the hijacking of Lufthansa Flight 181 at the peak of the German Autumn. The pace picks up, and we see a series of captions:

October 1977: Mogadishu, Somalia.

Pilot executed.

Plane stormed.

Hijackers killed.

Stammheim, Germany.

RAF leaders found dead in cells.

At this point, instead of showing stock images of corpses in Stammheim (as, for example, Feldmann and Richter do), Grimonprez reverses the chronology and inserts an earlier clip of Gudrun Ensslin being counseled by Otto Schily, the young litigator who would later become the Minister of Interior affairs under Gerhard Schröder. After this interjection, the tension of the Landshut standoff is broken with an odd bit of tape from the Mogadishu control tower. Grimonprez’s caption—“Hijackers order birthday cake and champagne for stewardess”—comes from the official record. One of the Lufthansa flight attendants did have a birthday during the abduction, and the Palestinian agents did request party refreshments. The hijackers were addressing a viewership that would extend far beyond their place and time. They wagered that films of their operation would be played and replayed for generations to come, for its documentary value as well as its dark humor. Here Grimonprez clearly indicates the date “1977” at the bottom of the screen, but the historical moment in Dial History is a continuous, media present. Grimonprez’s compositional strategy distinguishes his film from the anti-aesthetic of The Dead. Accelerating, slowing, and freezing the frames, his postmilitant project exposes how militants and terrorists have exploited the linear coordinates of media time in their campaigns.

Dial H-I-S-T-O-R-Y, dir. Johan Grimonprez, 1997. Film stills.

Dial H-I-S-T-O-R-Y, dir. Johan Grimonprez, 1997. Film stills.

When

Dial History was screened at documenta X, some viewers warned of a danger in the film: Grimonprez had risked dehistoricizing and aestheticizing violence.

26 Indeed, as it scans from site to site, the film provides only partial information about the place and time of each event. The various actors that figure in the film—for example, Soviet dissidents, Black Nationalists, and PLO guerrillas—are wrested from their material circumstances and dissolved into a thin veneer of optical effect. But the persistence of this operation in

Dial History suggests that Grimonprez is pushing precisely this point. The film asks the viewer to consider the correlations among different forms of militancy and terrorism. It also asks us to imagine that the occasion for political radicalism has not yet passed. If Feldmann, in

The Dead, shows the German armed struggle to be a closed chapter, Grimonprez puts the history of the RAF into a contemporary nexus of social, historical, and political antagonisms. Comparing these works, we encounter a paradox of postmilitant art. Feldmann turns to the certitudes of chronology in an attempt to articulate a moral code for

The Dead. But his recourse to documentary objectivity risks forfeiting both the social and aesthetic dimensions of cultural practice that are necessary to such a code.

The Culture Industry and the Counterpublic Sphere: Adorno and Rainer

Bringing into the same scope

The Dead, the

Baader-Meinhof Photographs, and

Dial History, we approach the critical terrain that Adorno plotted out in “Toward a Theory of the Artwork.” Composed in the same years that the New Left was rising up in West Germany, and published posthumously in

Aesthetic Theory in 1970, the year that the Baader-Meinhof group broke onto the scene, Adorno’s essay explores the relationship between documentary and aesthetic production in a way that illuminates some of the problems that have subsequently emerged in postmilitant culture. He draws upon Walter Benjamin’s reflections about the difference between art and documentary production and refines his own distinction between the discourse of art (

Kunst), on the one hand, and the particular artwork (

Kunstwerk), on the other.

27 Many works objectively are artworks, even when they don’t present themselves as art, Adorno argues, for although certain works can be regarded as art, no real art can function like a work. The transfer operates in only one direction: from work to art, not the other way around.

Adorno doesn’t identify a particular instance of the artwork that tends toward art, perhaps as part of his rhetorical strategy. However, he does describe an example of art that attempts to present itself as an artwork, but fails: his example is documenta. At the time of the essay’s composition, three documenta surveys had been held—in 1955, 1959, and 1964—and the 1968 installment was already being promoted in the press. Adorno remarks that the choice of the term “documenta” as the title for the exposition was inauspicious, for it “glosses over” the persistent divide between art and the document that impedes any circuit that would run from art to artwork.

28 This blind spot in the documenta vision, then, actually undermines the modern curatorial project. In suggesting some equivalence or exchangeability between art and document, Adorno argues, the organizers were abetting the very historicist, aestheticized consciousness that proponents of contemporary culture should want to oppose. The documenta initiative, by privileging the documentary function of art, returned to the affirmative, conservative folds of the culture industry.

The curators of the Berlin Kunst-Werke made the same misstep in Regarding Terror. Surveying the cultural fallout of the RAF, they seemed stunned by the mass media forces that had been unleashed during the 1970s, 1980s, and 1990s. Instead of illuminating the differences between documentary and experimental representations of the Far Left, they chose a curatorial tactic that reinforced and corroborated the official, public order of information. But postmilitant critique calls for another strategy, one that challenges the limits of this discursive space. We find this in the work of the American filmmaker Yvonne Rainer. Her attempts to produce a cinematic counterhistory of leftist militancy and terror open up a particularly dynamic platform from which to regard the RAF.

Rainer’s film

Journeys from Berlin/1971, like the work of Richter and Grimonprez, accentuates the tension between chronological documentation and aesthetic invention. Made in 1978–79, it contemplates a range of interrelated topics: history and protest, gender and psychoanalysis, and suicide and terrorism. The film was shot mostly in black and white in Berlin, New York, and London, and was performed in English. Two hours long, and one of the most demanding films to watch in

Regarding Terror,

Journeys stands out within the field of postmilitant culture. Indeed, its aesthetic difficulty brings it to the cusp of a new militancy. The film consists of multiple “tracks,” as Rainer calls them, which include historical time lines, dialogues, and mass media images. Interspersed among them are extended narratives from the psychoanalytic therapy of a middle-aged woman, played by the film theorist and art critic Annette Michelson, and a documentary sequence of Yvonne Rainer, herself, reading a letter to her mother. The tracks are laid out in complicated and, at times, contradictory ways. Text, sound, and image underscore, overlap, and cancel one another out. In her notes to the script, Rainer indicates that the film’s composition aims to allow a range of “meanings [to] emerge across the interconnectedness” of the tracks.

29 This interplay distinguishes

Journeys markedly from both Feldmann’s

The Dead as well as the guiding principles of the Kunst-Werke exhibition.

Each track is a “journey” that takes the viewer through space and time, leading her toward a new horizon of social experience. Rainer’s explicit, mannered manipulation of the visual and temporal components of the film is emphasized right from the beginning. The screen is black; there is no image. We hear sounds of work being done in a kitchen, and then conversation between a man and a woman who remain unnamed and unseen throughout the film.

30 The man unpacks a few groceries and says he’s tired. The woman replies, “I’ll cook.” Then plain white text scrolls across the screen. Its content appears incongruous with the conversation. “Let’s begin somewhere” are the first words to appear. There follows a chronological account of confrontations between militants and state authorities in postwar Germany. The text outlines a number of legislative changes, including restrictions on public dissent, the banning of the Communist Party, and the mandate of compulsory military service everywhere but Berlin. Next the text lists flash points in the history of the RAF’s first generation: Baader and Ensslin’s arson attack in Frankfurt in 1968, the passing of the Emergency Laws later that year that consolidated the state’s monopoly on violence, the RAF’s direct actions, and finally the arrests of each leader and their subsequent deaths while in Stammheim in 1976 and 1977.

Date comes After date, but Rainer interrupts this forward progression with a tangle of threads, both pictorial and narrative. Countering the motion of the time line’s upward scroll is a series of horizontal tracking shots that recur throughout the film. The camera pans across a mantelpiece decked with an assortment of objects.

31 Among household items such as a teapot, dishes, and bottles of pills, Rainer displays books by Walter Benjamin and Freud, a paving stone, a pistol, and a photograph of Meinhof at the Cologne-Ossendorf prison (the same look-that-could-kill picture that Feldmann uses in

The Dead). The assortment changes slightly with each pass of the camera. In one instance, an actor’s open hand hovers among the row of stationary objects and holds a snippet of newspaper between two fingers. This incursion animates the mantelpiece tableau and plays against the forward march of the black-and-white text.

Journeys from Berlin/1971, dir. Yvonne Rainer, 1980. Frame enlargements.

Journeys strikes across several boundaries of separation: temporal, spatial, social, and ontological. Rainer’s close attention to the divide between public and private spheres distinguishes the film from most of the artworks in

Regarding Terror. This concern was evident in her earlier work as well: Rainer began her career as a dancer, but turned to filmmaking in the late 1960s and 1970s in an apparent attempt to explore the medium’s potential for “intersubjective experience” and communication among speakers. When Rainer came to spend a year in West Berlin, she must have found a powerful accord with her ideas, for debates on the public/ private dynamic were active in the city’s intellectual and artistic circles. Whereas local feminists elaborated their claim that “the personal is the political,” members of the New Left discussed the weakening of social bonds. Writers such as Peter Schneider and Karin Struck picked up on this shift, exploring new sensibilities and individual subjectivity (

Neue Subjektivität); their work, often autobiographical, focused on introspection and “personal authenticity.” Meanwhile, many activists and policymakers across Germany worked to counter social apathy by increasing access to public institutions, government offices, and the media.

Journeys from Berlin/1971, dir. Yvonne Rainer, 1980. 16mm, color, 125 minutes. Frame enlargement.

The key terms of these debates had been framed by Habermas in

Structural Transformation of the Public Sphere (1962). A decade later they were reframed by Oskar Negt and Alexander Kluge in

Public Sphere and Experience (1972). With the dual threats of homegrown terrorism and state repression, doubts began to emerge in the 1970s about the capacity of the German public sphere to accommodate rational and critical exchange between individuals and the authorities. Habermas surveyed this changing arena in a set of articles that warned against a collapse of distinctions between public and private spheres. This breakdown appeared most evident in the mass media, especially once reporters unleashed a veritable “witchhunt” (

Hexenjagd) to smoke out RAF members and their “sympathizers.” Extensive coverage of RAF actions would become a case in point of Habermas’s disquiet about the collapse of distinctions between public and private. The media surge combined with the state’s tightening controls on civil liberties and entered deeply into the personal experiences of every German who read a newspaper, listened to the radio, or watched television. Negt and Kluge moved beyond Habermas’s analysis to actively oppose the hegemonic forces of West German media conglomerates. Their collaboration called for cultural producers to envision alternative means of social experience: not just to participate in the public sphere, but rather to establish a

Gegenöffentlichkeit, or “counterpublic.” We might imagine

Journeys from Berlin as a response to their appeal.

32There is an intersection between Rainer’s counterhistory in

Journeys and Negt and Kluge’s concept of the counterpublic. The tracks that compose the film negotiate the effects of historical fragmentation; they mediate between individual perception and social parameters. Rainer layers the film with an array of sources—historical, contemporary, documentary, and fictional. The narrative moves back and forth between the time of the film’s production (1978–79), the Russian Revolution, and Rainer’s own life in 1971. Rainer’s intersubjective reach allows the film to challenge the understanding of the German Autumn to an extent that few other artists have sought to do. This challenge is subtended by Rainer’s stance on sexual politics. As she noted in an interview in 1980, certain options present themselves “more readily” to women than to men: “suicide in the personal sphere, assassination in the political.”

33 Journeys permits the viewer to identify with the situation of RAF members, focusing in detail on Meinhof. But at the same time the film draws fundamental distinctions between Meinhof’s circumstances and those of other radical women who came before her—Rosa Luxemburg, Emma Goldmann, and the “Amazons” of Bolshevik Russia.

34 Investigating the historical contexts of the armed struggle,

Journeys moves beyond the mass media temporality of the Kunst-Werke’s

Regarding Terror. It opens up a counterpublic space in which to critically engage the individual choices that Meinhof made. The space that Rainer opens up is a feminist one.

Under the Sign of Antigone

As Journeys approaches its conclusion, Rainer lays the groundwork for a close reading of a letter that Meinhof wrote at Stammheim, briefly before her death. But it is the sequence directly preceding it that presents Rainer’s sharpest analysis of Meinhof’s militancy. Here she interweaves two tracks to produce a dialectical reflection on social action and intersubjective exchange. One track plays a dialogue between two speakers (identified in the script as He and She), the other (a patient’s monologue from a therapy session) cuts in and out of the conversation. He and She are disembodied voices; when they speak, the viewer sees only a static image of loft windows. The patient’s face, in contradistinction, is filmed. Rainer places the camera directly across from it, so that it is viewed from the therapist’s perspective.

The sharp cuts between the dialogue and the analysis combine with the periodic blanking out of the patient’s lines. This impedes any direct access to meaning and foregrounds the apparatus of the film’s own production. In the dialogue, the speaker She discusses the difference between the RAF’s circumstances and those of earlier activists, especially the militant women who appear elsewhere in Journeys. The problem with Ulrike Meinhof, She notes, was that she turned her attention away from the complexities and contradictions of the public sphere and toward herself. Without recourse to the larger networks of social activists in Germany or abroad, Meinhof and the other self-styled martyrs of international resistance set themselves on a path to destruction. Moving underground, they allowed themselves no margin of error.

As Rainer’s speaker sees it, one moral of the German Autumn is that the “heroic” autonomy for which the RAF struggled ultimately cut the group off from its constituency and foreclosed possibilities for radical change. This questioning of autonomy is recast in the patient’s monologue. Becoming a “free agent,” she realizes, came at the price of “suppressing everything—thought, feeling, doubt.” These remarks on “perfect detachment” echo the strident convictions of Meinhof’s writings, from her earliest pleas for the release of Baader and Ensslin to the last pages of her prison notebooks. The means by which Rainer elaborates this critique are complex; they fully exploit the medium of cinema to advance a feminist proposition. In one track, the speaker She considers the need for humility, not heroism, to make social justice possible. Addressing an unspecified but presumably leftist constituency as “we,” she puts it like this: if we accept our own “fallibility,” we might take greater risks in using our power “for the benefit of others.” This can happen by “inhabiting” our own history and “resisting inequities close at hand.”

35 In the second track, the patient reflects upon the necessary role of “compassion”—for the self and for others—in imagining political alternatives. Rainer miters together the two tracks in a way that both heightens the tension between them and primes the viewer to respond skeptically to Meinhof’s concluding letter.

Consider this excerpt from the screenplay:

| Image |

Sound |

| |

|

| Loft windows. |

SHE: … risks in using one’s power … |

| Therapy session. |

PATIENT: Hmm … Suicide, then, can be seen as a failure of the imagination … |

| Loft windows. |

SHE: … for the benefit of others … |

| Therapy session. |

PATIENT: … a failure to imagine what may lie outside one’s own experience … |

|

SHE: … working with people |

|

PATIENT: … a failure to imagine a world … |

| Loft windows. |

SHE: … inhabiting one’s own history … |

|

PATIENT: … where conscious choice … |

|

SHE: … resisting inequities close at hand … |

| Therapy session. |

PATIENT: … and effort … |

|

SHE: … risks in love … |

|

PATIENT: … might produce mutual respect … |

|

SHE: … mistakes … |

|

PATIENT: … between you and me.36 |

In this sequence the narrative comes together and breaks apart between the two women’s voices, allowing for philosophical reflection. The women do not address each other directly, and it is unclear whether they occupy the same moment in time, but they are nonetheless made to speak together through the film’s composition. Their closely interspersed lines allow the audience to note the correspondences between their utterances. First “power” counters “failure,” and then the words “conscious choice” and “resisting inequities” resonate, if only briefly, as a single concept. Rainer’s precise editing of these two tracks approaches a synthesis, for example, in the patient’s proposition that “conscious choice … and effort … might produce mutual respect … between you and me.” However, the incursion of the word “mistakes” complicates any easy resolution. Between the two tracks Rainer lets a counterpublic sphere unfold, a sphere that is full of obstacles but which nonetheless serves as a site for the kind of detailed negotiation of power that RAF militancy and terror refused. A dialectic obtains in

Journeys, yet it doesn’t point toward Hegelian sublation. Rather, like the open-ended helix of Adorno’s critical imagination, this is a materialist and negative dialectic, one that seeks proximity and recognition, but not domination or reconciliation.

37Rainer’s notion of “mutual respect” recalls the reciprocal recognition that is yielded in Hegel’s struggle between two subjects in the

Phenomenology of Spirit. Indeed we can find several points of contact between the premise of

Journeys from Berlin and Hegel’s master/slave dialectic, but the points of divergence are what take us furthest into a postmilitant critique. As critics have noted, Hegel’s elaboration of the relation between identity and difference is at the center of the feminist project to realize freedom and equality. But where Hegel discusses sexual difference, for example, in the

Phenomenology as well as the

Philosophy of Right, he places limits on women’s agency that both reveal and reinscribe male domination. These limits also disclose the aporias of his own dialectical philosophy, showing it to be a totalizing system of identity logic. Hegel’s feminine ideal, of course, is the classical figure Antigone, one of the muses of postmilitancy, as I have argued.

38 Although Antigone doesn’t appear in

Journeys, Rainer’s investigation into the matters of gender, justice, and suicide puts the film directly under her sign.

The postmilitant Antigone remains closer to the narrative of Sophocles’s drama than she does to Hegel’s handling of her role. She embodies the tragic conflict between law and kinship, but she also represents the history of “the revolt of women who act in the public sphere on behalf of the private sphere,” as the political theorist Patricia Mills maintains.

39 Sophocles’s Antigone prefigures the “Amazons” recalled by Rainer in

Journeys, the women for whom suicide and assassination might have once been legitimate political choices. Hegel, as many have remarked, devotes little attention to the ethics of Antigone’s self-liquidation, which is the climax of Sophocles’s drama; this elision disconnects aspects of the tragedy that are germane to feminist analysis, in general, and postmilitant critique, in particular.

In the Sophocles play the dramatic tension pivots around the gendering of political agency. Antigone breaks the boundaries of the private sphere to act within the polis, and her suicide refutes patriarchal authority. Sophocles emphasizes Antigone’s place within the community of women. This is different in Hegel’s reflections, since the dialogues between Antigone and her sister Ismene—so central to the establishment of her character—are all but ignored. As Judith Butler has noted, Antigone, for Hegel, “passes away as the power of the feminine” and instead “becomes redefined” as a more narrowly maternal figure that serves to defend the family.

40 The

Phenomenology, in particular, holds as ideal the male-female relationship of identity-in-difference (for example, between Antigone and Polyneices) and leaves no space to consider the allegiance of sister to sister or woman to woman. In

Journeys, as in some of the most incisive works of postmilitant culture, Rainer underscores the tremendous power of relationships between women. In the film’s mitered tracks, cited above, we see this through the provisional and strategic exclusion of the male voice. The crucial moment of recognition comes between Rainer’s two female voices: She and the patient. What the speakers realize together is both the lesson of

Journeys and a retort to the violence of the RAF. The mortal acts of Meinhof and the others could not offer a “promising fatality,” as Butler has called Antigone’s suicide.

41 Instead, these acts signified a failure of the imagination.

Rainer’s intertwining of the two tracks sets the stage for the film’s conclusion: a voiceover of one of Meinhof’s last letters, which she wrote to another RAF member, Hanna Krabbe, from her Stammheim cell. Here, weeks before her death, Meinhof sounds as furious with her comrade as she was with the criminal justice system and, indeed, herself. Rainer handles the letter skeptically in her film and suggests that the conditions for protest and opposition have substantively changed since the time of the Russian Revolution. In the 1970s and 1980s the situation was not as clear-cut as it was in the early twentieth century, when Rainer’s Amazons were fighting “the good fight.” Politically active women had more options than the struggle unto death. Today, I would argue, they have even more. To actualize these options, however, requires reflection, collaboration, and persistence.

Journeys maps out a counterpublic sphere. To make the film, Rainer dug into the terrain of RAF terrorism, reading the group’s writings, exploring their objectives, and seeking out points of contact between her own life and the lives of the Far Left. This endeavor, together with Rainer’s editing strategies, sets

Journeys apart from

The Dead, the

Baader-Meinhof Photographs, and

Dial History. But, more than this, it also affords us a crucial perspective on the gains and losses of militancy. With its open-ended and counterhistorical structure, the film gestures toward a means of intersubjective recognition that is as much at odds with the RAF’s tactics as it is with a hypermilitarized state apparatus. As we see in Rainer’s editing of the women’s two voice tracks, this means of recognition refutes Hegelian reconciliation, or what Adorno has called “the philosophical imperialism of annexing [that which is] alien.”

42 Instead Rainer puts her two speakers into a proximity that preserves difference—in other words, she establishes a situation in which mutual respect might be accorded. One of the morals of

Journeys goes beyond the Kunst-Werke’s approach to the RAF: Rainer shows that social justice must be realized through collaboration, not violent confrontation.

Post-Mortem

If the media time line that structured

Regarding Terror implied an Idealist notion of historical progress, the curators’ selection of Slavoj

Ži

žek as the central theorist of the exhibition pushed the Hegelian references further to the fore. The catalogue essay “Das Unbehagen in der Demokratie” (“Democracy and its Discontents”), like much of

Ži

žek’s writing, grounds its arguments in a particular reading of Hegel’s philosophy and then directs them toward an exegesis and validation of psychoanalytic theory. Among contemporary critical theorists,

Ži

žek is one of the most perceptive surveyors of subject formation, complicity, and collective action; his best works reveal the deadlocks of democracy and indicate viable channels out of them. But this essay doesn’t really address the deeper meanings of leftist violence and its representation.

43 In line with the curatorial plan of

Regarding Terror,

Ži

žek tabulates the twentieth-century history of revolutionary events and portrays the RAF as a symbol of what Biesenbach, in his introduction to the exhibition catalogue, calls Germany’s “singular, but missed chance … for a greater democracy.”

44 Unlike Rainer,

Ži

žek doesn’t acknowledge the social and political contexts that surrounded the RAF; as a result he gives up the chance to assess the long cultural decay that has followed upon their attacks. What his essay does offer, however, is a peculiar, if not perverse, assessment of suicide as an effective mode of resistance.

Ži

žek argues that activists and social theorists on the Left have failed to recognize the authentically transformative potential of “self-violence:” what he describes as “the violent re-formation of the very substance of the subject’s being.” His essay ventures to reposition armed resistance as “the ultimate political version … of the Hegelian process of

Bildung [or] educational self-formation.”

45 What the RAF grasped,

Ži

žek maintains, is that intellectual reflection can’t break the ties of subjection. Instead, liberation must be “staged” through masochism, since this performance, in his words, discloses “the simple fact that the master [the state, the father, the law] is superfluous.”

46 Despite the advantage of thirty years of hindsight,

Ži

žek misses a reality that some of the earliest works of postmilitant art gave body to: the RAF’s hunger strikes and suicides convinced most Germans that the group was a danger to society, giving the authorities ample opportunity to roll back rights that the first postwar administrations had written into the federal constitution. As the political scientist Ulrich Schneckener has demonstrated, RAF masochism prompted the state to strengthen its controls.

47 So, in the end, did the RAF’s sadistic campaign of bombing, abduction, and murder.

In the last line of his essay,

Ži

žek offers a few sober words of warning—that the RAF’s direct actions should be condemned—yet his goal is clearly to illuminate the “potentially redemptive disciplinary drive” of the initiatives that challenge dominant institutions of liberal democracy. To this end, he identifies the (mistaken) rationale of the Far Left: only “violent intervention” and radical “externality,” not political education or consciousness-raising, could undo the alienation that gripped the FRG in the postwar years.

48As we have seen, selected artworks in

Regarding Terror convey messages consistent with

Ži

žek’s argument. At several points in the Kunst-Werke project, the curators noted that some contemporary artists consider the RAF, like other militants and terrorists, to have superseded the signifying power of aesthetic practice. After October 1977, After September 2001, why paint another

Guernica? This challenge, implicit in much of the exhibition, is significant. For if RAF members actually attained the advanced, “external” position that

Ži

žek indicates, it was only through their suicides—acts of utter dejection. We have to ask, in fact, if the leaders of the German armed struggle really achieved this externality. When the first generation began to appear in the headlines and on the nightly news, their acts became prime media feed. By the time the second generation was staging Schleyer’s forced confessions and dispatching the videotapes to national broadcasting networks, the conditions of any Baader-Meinhof revolution became clear: it would be televised, or it would not be at all.

49 As Jean Baudrillard noted early on, by playing to the mass media, the RAF entered into the internal dynamics of that same media “machine.”

50 Today we can take this insight further. Looking back at the German Autumn, we see that the RAF was speaking not just to publishers and broadcasters, but also to the dominant public sphere, which those media outlets serviced. Soon After its inception, the group disconnected from the social movements that opposed the status quo as well as the vital counterpublic forces that bound those movements together.

Flawed as it was,

Regarding Terror—or something like it—was bound to happen, for postmilitant culture was reaching critical mass After the al-Qaeda attacks of 2001. Perhaps the Kunst-Werke was only the quickest to shoot in a game of curatorial inevitability. We can credit the exhibition, in its strengths as well as its flaws, for designating a space in which to reexamine German militancy and terror; the Biesenbach team initiated several productive debates in the public sphere; indeed, we might see Wolfgang Kraushaar’s indispensable study of the German armed struggle,

Die RAF und der linke Terrorismus (2006), as a timely, scholarly response to the Kunst-Werke controversies. Only one essay in Kraushaar’s two-volume set squarely addressed

Regarding Terror, but many of the contributors acknowledged the heightened tension between aesthetics and politics in the postmilitant culture that developed in Germany in the early 2000s.

51If

Regarding Terror didn’t provide answers as to why the Far Left has interested so many artists, it still added urgency to this question. Today, more than thirty years After the German Autumn, we can offer this proposition as a response: since the RAF’s ascent in the 1970s, some have understood the possibility of “the most radical gesture” (a situationist concept) to exist only within the media or on the streets, but not in the production of art.

52 As a character in DeLillo’s

Mao II puts it, now we look to the news for emotional experience that culture no longer makes available.

53 Artists, in particular, seem to have sensed that the RAF’s direct actions commandeered the field of symbolic exchange. But if revolutionary violence appeared to exceed the signifying capacities of visual art in the 1970s and 1980s, certain critical minds have sought to reverse this operation.

Whereas much postmilitant culture seems unable to do more than copy or collage reporting on terrorism, some artists nevertheless strive to disenchant the violent idols of the mass media. Rainer makes this move in

Journeys from Berlin/1971. Others seek to disrupt the purported documentary objectivity that curators and editors have recently favored. The impulse of Grimonprez’s

Dial History, for example, lines up with this latter tendency, unsettling the documentary terms of the “ever-falsifying photography” that Adorno examined in

Aesthetic Theory.

54 And in her film Rainer contrasts fictions with factual documents to take the viewer to the crux between counterhistorical time and counterpublic spaces. Disclosing the important distinctions between Europe’s early revolutionary struggles and the modes of postwar protest and resistance, this film, like some of the most compelling works examined in this book, shows the postmilitant turn as a signal moment in late modernity. Had the Kunst-Werke curators foregrounded the aesthetic strategies of Grimonprez, Rainer, and other critical and resistant artists in their planning,

Regarding Terror might have added new depth to the debates about the cultural response to militancy and terror.

Maybe it was the funding problems and press frenzy surrounding the RAF show that put the Kunst-Werke on guard, distracting it from the mission of analyzing the visual mythologies of the Baader-Meinhof group. Instead, its museal program defused the contributors’ means of critical analysis and returned the viewers to the premises retro-styling and the déjà vu. Aesthetic innovation and historical reflection were of secondary importance in both the exhibition and the catalogue. Biesenbach’s project gave in to the anti-aesthetic that DeLillo diagnosed in his novels and Grimonprez recalled in his film, whereby “the more clearly we see terror, the less impact we feel from art.”

55 That the curators continued in this direction—possibly against their original intentions—brought the exhibition into accord with the RAF’s own failures. Without a viable agenda, members of the RAF shunted their energies from social change to self-obsession. The Kunst-Werke made a parallel move in

Regarding Terror. In their appeal for immediacy, in their anti-aesthetic wager, the curators got caught in their own media spectacle. From there, they tilted a degree toward the RAF’s long arc—the arc that fell on the terrible night of October 18, 1977.

Since that darkness began to set in, the task of the postmilitant critic has been not just to overcome the German Autumn, but to try to understand it. Indeed it is really only at this moment, as Hegel might have noted, that our work begins, that we spread our wings, like the owl of Minerva, and take flight.