|  |

By

Djeli A. Griot

Makami stumbled, almost falling. The orange-colored cat he had nearly run over went still, the hair on its back raising. Its eyes reflected in the night, seeming to ask what bit of chance had caused their paths to cross in the sand-ridden backstreets of this small town, which only rats and shadows should have called home.

The answer came at the sound of heavy footsteps from somewhere far too near. Makami resumed his run, turning a corner while daring a glance back. The empty streets did not fool him; he was still being hunted. Who his pursuers were and their purpose in this mad chase was what baffled him.

He had noticed them earlier, like two jackals creeping after prey. They kept their distance, but their intent was too obvious. Makami had been a thief once—in fact, a rather good one. He had followed those he marked whole days, tracing their routines until he could predict their every move, waiting until they were most vulnerable and distracted to take his prize. It was done so seamlessly; most were not aware of the theft until he had long departed. Others however were not so artful—choosing to cudgel their victims senseless or leave a blade between their ribs, before seizing what they wanted.

Still, wrapped in torn and tattered clothing, Makami could find little to mark him as worthy prey. Unless these thieves were so desperate, they now took to robbing paupers and beggars, these men hunted something more. But what? Had some merchant gotten wise to food he daily snatched at market? Unlikely. He could manage such simple sleight-of-hand in his sleep. Besides, the scraps were barely noticeable—certainly not enough to keep his belly from crying to him each night. No, these jackals were after more. He only wished he knew what.

The pain was sudden. One moment he was running, the next he was on his back. Bits of light danced before his eyes and he scrambled to get his bearings. Lifting a hand to his brow he felt something warm, trickling from where he knew a wide gash had opened upon his dark skin. Blood. Something had struck him as he rounded a corner, right across the face, with enough force to send him crashing down.

Dazed, a dark form took shape in front of him. It was a man—a very big man. His rounded head was cleanly bald, making it look as if his entire body were covered in one sheet of ebony. He gazed down with a scowl, pulling his spread out features closer. Bulbous and stocky, he had shoulders like an ox and meaty arms that Makami guessed were just as strong. In one hand he held a misshapen staff of wood crowned with a thick knot. Long dark cloth encircled his waist, covering his legs and coming to his ankles. His torso was left bare—save for two hide straps that crossed his chest. Up to three knives were tucked inside, their blades gleaming like sharp teeth. Little doubt about it, Makami thought grimly, this was definitely a jackal.

“Stay down,” he growled, lifting his cudgel threateningly. His breath was labored and his massive chest heaved with considerable effort. “Should hit you again for putting us on such a chase.” He looked up at the sound of approaching footsteps. “Over here! I have him!”

Still too dazed to turn around, Makami waited until the new arrivals came into his field of vision. Two more men. The jackal pack was complete. One was muscular, dressed much like his larger companion. He paced the small space, dull yellowish eyes threatening danger. The third man bent to his haunches, his dingy tunic parting just below the knees as he balanced his slight weight. He ran a hand across the triangular patch of hair atop his scalp, smooth brown forehead furrowing in thought. His bright inquisitive eyes remained fixed on Makami—as if trying to discern something. After a moment he broke into a grin, displaying perfect white teeth unnaturally large for his wiry frame.

“Now that wasn’t so hard,” he said. “Good thinking Ojo, leaving you out here ahead.” He continued to grin at Makami, which seemed even brighter than the gold-hooped earrings he wore in each ear. “Didn’t know there were three of us eh?”

Makami didn’t answer. This was gloating, not a question. These men were decidedly not thieves. They all spoke trader’s tongue, each tinged with differing accents. So they weren’t locals either.

“Still say we should have waited,” the big man grumbled. Makami noted something in his voice. Was it...worry? “We were warned—”

“Oh, stop your old woman talk Ojo,” the smaller man said impatiently, coming to his feet. “Doesn’t look like much to me and we took him easy enough. We’ll keep him locked tight for the next few days.” A new light came into those bright eyes, reminding Makami of a ferret. “Or, maybe we might get more for him ourselves . . .”

Makami frowned. Get more for him? Were these men slavers?

“I don’t know Matata,” the big man said. Yes, there was definite worry there. “What do you think Jela?”

Their silent companion only shrugged; those yellow eyes trained on Makami. “Matters not to me.” His accent was so thick it was obvious these lands were foreign to him. And for the first time Makami glimpsed his teeth—each of them filed to sharp points, giving his mouth the appearance of a shark. “Whichever one brings us the greater payment.” He pulled one of the knives strapped to his chest, aiming a deeply curved blade directly at Makami. “You. Show it to me.”

Makami stared up at the man perplexed. Show him? He shook his head, not understanding.

“I will not ask you again,” the man warned, his voice betraying an edge as sharp as his cruel-looking blade. “Show me what lies beneath, what is on your chest—I want to see it myself.”

The blood drained away from Makami’s face at the man’s words. How could these men know about what he had taken such great effort to conceal? And if they did, to ask such a thing, were they mad? Beads of sweat broke out across his skin as for the first time, he truly became frightened.

The man scowled deeply, displaying his sharpened teeth. With his free hand he delivered a blow, snapping Makami’s head back and filling his mouth with fresh blood. Suddenly numerous hands were upon him. A blade flashed and there was the sound of cutting cloth. Summoning what strength was left in him Makami attempted to twist away from his attackers. But the big man was true to his earlier threat, rapping the back of his skull once with the cudgel. The blow crumpled him, leaving his head dizzy with new pain. Listless, he felt as the shirt that covered him was pulled and ripped until it lay at his waist in tatters. He was left on his knees; chest now bare as his captors stepped back to admire their handiwork.

“Oja!” the big man exclaimed in his native tongue. “Curse my eyes! Are they moving?”

Makami closed his eyes, not needing to look down at his chest to know what the man was talking about. They were markings, crimson lines and arcs etched into a circle upon his dark skin. And like always, they were moving—sliding across one another in a chaotic dance, spinning about a hollow center as if searching for order. He could feel them, whether awake or in slumber, always moving just beneath his skin. They had become a part of him—his own never-ending curse.

The muscular man, the one they called Jela, came forward, pointing the edge of his blade directly at the markings.

“No,” Makami pleaded. “Please. Do not . . .”

“See here Jela,” the smaller Matata laughed. “He thinks you will gut him like a goat.”

The muscular man grunted. “He is worth more alive than dead. Only wanted to see what all this trouble was over.” His dull yellowish eyes followed the crimson markings that continued their peculiar dance. Grabbing Makami by the chin, he lifted his head until their gazes met. “How did you come across such a thing?” he asked. “How do you make them move?” Getting no answer his tone became derisive. “Cease your trembling. We are not the ones you should fear.”

Makami glared back at the man. Fear them? No, he did not fear these men—he feared for them.

Already the markings etched into his chest had begun to move faster. They burned now, the pain building quickly until it felt like hot irons seared his skin. The arcs and lines were coming together, placing themselves into a pattern like a puzzle. His captors stared at the markings, mesmerized by the display. He tried to speak to them, to warn them to run, but the agony that now consumed him stole his speech. As the markings finally settled and went silent, he knew it was already too late.

“What is this?” the muscular man whispered. He brought the tip of his blade to touch the new symbol that the markings had formed onto Makami’s chest. The knife pushed through the pattern with ease. What should have been human skin rippled as if it were water. The man quickly pulled his hand back, those yellowish eyes going wide. And then the nightmare began, again.

Makami felt the thick tentacle shoot from his chest, and watched as it wrapped itself around the man’s neck. This part was always painful, and he screamed out now. More of the tentacle pushed out of him, a dull grey fleshy mass that reminded him of an octopus, only much larger. It squeezed tighter around the man’s muscular neck, lifting him off the ground. Those yellowish eyes bulged as he dropped his knife, fingers clawing in vain at the coiling appendage while his legs kicked wildly. Behind him, his companions only stared in horror, backing away slowly—none daring to come to his aid. The doomed man let out a choked gasp of spittle and blood which was followed by an audible crack. His head fell to one side, hanging limply, looking like a swollen bit of rotten fruit. The rest of his body twitched in spasms as if celebrating its sudden and short-lived freedom, before going still.

Makami watched as a second tentacle emerged. Another quickly followed. And then another, until there were more than he could count. They pulled and heaved, making their way out of his chest in a constant stream, piling onto the ground before him. When the last of them flowed out of him he fell back, weakened and delirious with pain. As he lay there on his side, he gazed up at the nightmare he had given birth to.

The many tentacles were part of one being, a monstrosity that was only now rising to its full height, towering high above the remaining witnesses in the deserted alley. Nothing so immense should have been able to come out of his small body, but it had. Its many appendages writhed about, twisting and turning on themselves, burying away whatever lived within the horrid mass. The dead man in its clutches was pulled deep into its fleshy center, disappearing to whatever fate awaited him.

The smaller man, Matata, seemed to decide he had seen enough. Without a sound he turned, breaking into a run. As if sensing his movement, a tentacle shot towards him, catching him by a leg. He cried out as he went down, his face hitting the ground hard. As he was pulled towards the writhing mass, he tried to grab onto something, but only the dusty street gathered beneath his fingers. Between his bloodied and broken teeth, he began to whimper, calling out a desperate prayer in an unfamiliar language to unfamiliar gods. Makami remained where he lay, listening to the man in pity. He himself had prayed enough in the past weeks for them all—and to no avail. Either the gods did not hear, or they did not listen. He watched as the hungry tentacles enveloped the small man, silencing his cries forever.

Only the big man was left. He stood there, his weapon dangling uselessly at his side. His eyes were wide, his mouth hanging open as he stared up at the great monstrosity before him in awe.

“Are you a god?” he whispered.

His answer came as the swarm of tentacles came crashing down upon him, burying him within.

Makami shut his eyes, unwilling to watch any more. He knew he had nothing to fear. Moments from now, the nightmare he had unleashed would return, through the very way it had come. The pain would be so great he would black out. And the symbol on his chest would break apart, returning to the circle of crimson arcs and lines that would again begin their constant movement. That was the way it had happened before. And it was how it would happen again.

* * *

The fat man cursed in several mangled tongues as he lifted a long heavy stick, threatening to lash Makami with it. The two chins on his rounded face shook violently, as if joining in their owner’s anger. Makami stepped back quickly, almost overturning a stand laden with earthen pots. He pulled what was left of his shredded clothing about his increasingly gaunt frame, lest it slip, revealing what he so desperately sought to hide. Turning away, he walked back into the bustling crowd of the open market who parted for him—their eyes lingering with disgust.

He must have looked a sight, barely clothed in filthy rags, the reddish-dirt that passed for soil here caking his brown skin, and once well-coiffed bushy hair now matted into clumps. What he must have smelled like he dared not venture. That had been the sixth time he had been chased away, when all he asked for was work. He would do anything—haul goods, clean animals, even shovel ofal—just so it earned him enough to leave this place. He had thought he would be safe in this drab town of mud-bricked buildings with dust-beaten roads, so small that foreigners more than often outnumbered locals. It was more a way station than a true settlement, a place for caravans and merchants to rest, water their animals and trade for supplies—before they ventured out into the open desert. He had expected to disappear in this isolated place, away from the large cities he had once called home. But the night past had shattered any such hopes.

He had stumbled from the alley earlier this morning, his chest throbbing in pain, and his head filled with the faces of the three men he had killed. Or the thing inside him had killed. Is there a difference, he condemned himself guiltily. More troubling, they had known about the markings, which seemed impossible. Those that saw the strange lines etched onto his chest never lived long enough to speak of them. Yet these men had known, and they hunted him—claiming they would receive payment for his capture. But who? What madmen would dare seek out such horror and death? He ran a hand across his chest absently, where beneath his torn shirt he could feel the markings gliding beneath his skin. He had no answers to these questions, but he had to keep moving, until he could not be found by friend or foe. It was better for him that way; it was better for everyone.

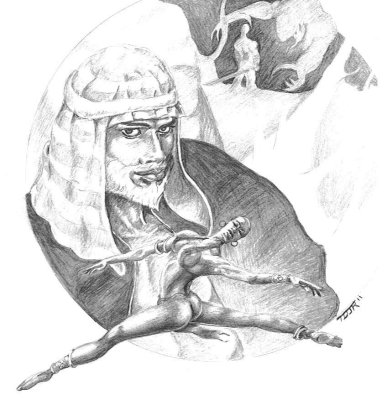

A familiar sound caught his ear, faint chanting and the beating of nearby drums. Curious he followed it, turning several corners until coming to an open clearing. There, in the center of a gathered crowd, atop a raised platform, several men pounded out powerful rhythms with their palms on ornately carved wooden drums. The instruments were slung across their bare chests, hanging at their sides where their palms could reach. Bright golden kilts embroidered with patterns hung from their waists to past their knees, offering a stark but fitting contrast to their dark bodies. Beside them were other men, these however covered in voluminous but equally brilliant colored cloth. They sat strumming and plucking their fingers across the strings of wooden instruments. But more captivating was the figure before them.

A woman stood in front of the drummers, dancing to beats with such ease and grace it seemed they had been created for no other purpose. Chest bare like the men that accompanied her, she wore only a girdle of beads and shells that covered her wide hips down to the top of her thighs. Muscles flexed and tensed across her coffee-colored frame as she swayed and shook, beads of sweat causing her oiled skin to glisten in the mid-morning sun. Her ornate hair was arranged in thick coils, held in place by rounded bits of gold. As she danced, she sang loudly in some faraway tongue, calling to the drummers who responded back with their own chants. Small metal balls attached to her wrists and ankles rattled in accompaniment to her every move, blending into the music.

Makami watched entranced. The drums and dance reminded him of his own homeland, that he had left so long ago. No wonder they called to him. But even more so, the woman and her dance evoked other memories. Kesse.

He closed his eyes, swaying slightly as a rare bit of peace settled over him. Beautiful Kesse, whose rich laughter always tickled his ears. Kesse who would sing softly and dance for him in the morning as the sun crept into their room. How he loved to watch her hips sway, drinking in the way her ample backside jiggled as she glanced back and smiled brightly. How he loved to nuzzle his nose in her bushy hair, or trace his fingers across her mahogany skin as she slept beside him. Kesse, who had been his life, who was now forever gone. Dead.

The reality of that one word crashed in on him, banishing the fleeting moment of happiness. His eyes flew open, and he was struck with such deep anguish any other pain dulled in comparison. He would have cried, but there were no tears left to fall.

The drums suddenly hushed, and the dancing woman went into a still pose lifting her arms high. The gathered crowd erupted into cheers and applause, many throwing tiny sacks, most likely filled with gold dust or other valuables towards the entertainers. Armed men with swords and spears kept the delighted onlookers at bay, while smaller children rushed out to collect the tributes of praise from the ground. A tall man wrapped in rich cloth that barely hid his fat belly lifted a staff and cried out praise for his performers, urging the crowd to shower them with more gifts—to which they obliged.

“You have a fine ear.”

It took a moment for Makami to realize the nearby voice was meant for him. He had become so accustomed to disgusted stares and curses; he did not expect conversation. A man walked towards him, a bright smile showing beneath a starkly white beard that adorned his brown face. Hands clasped behind his back, his belly surged before him, as if trying to escape the white shirt beneath his long indigo robes. He came to stand before Makami, a gleam in his dark eyes.

“I was remarking on your ear for music,” he said. Rather short and squat, he had to look up to meet Makami’s gaze. “The way you swayed, your eyes closed, as if you could feel it more than the rest of us.”

Makami didn’t answer. He felt more than this old man could possibly know.

“Would you care to join me at my tent?” the strange figure asked. “I am returning for mid-morning meal. I have more than enough to spare.”

Makami frowned now. This man was dressed well, not richly, but good enough to be a merchant or a trader. Why would he invite some filthy beggar from the streets to dine with him? He was suddenly gripped by fear, a hand clutching at his chest. Those men last night were to deliver him to someone. Could this be their paymaster? He stepped back slightly, eyes seeking a place to run. The old man must have noticed his alarm, for he lifted his hands in what was a common means of apology in these lands.

“The goddess burn my thick scalp,” he admonished himself. “You must think me a rude old fool.” He palmed his forehead before releasing it, nodding slightly. “Manhada, I am Master Dawan ag Amanani, of Kel Zinda. I offer you food and drink if you would have it, and do so in peace, under the sacred blessed goddess.” He stopped and offered a smile. “Charity is favored by the goddess. And you look as more worthy company than these other men—whose tongues seem only gifted at haggling.”

Makami took a pause to look the man over. The greeting was familiar to him—a ritual of the Amazi people, the desert-born—nomads who traversed the sands. Food and drink were offerings of peace, and were taken seriously, demanding that no harm would come to him under penalty of invoking the wrath of their gods. There was little safer oath he could ask for. As his stomach growled noisily, feeling as if it were folding in on itself, he found himself nodding—casting aside his inner doubts.

* * *

It was sometime later Makami sat upon the colorful and richly decorative rug, shielded from the hot sun outside a large tent, rubbing his sated belly in content. It had taken all his self-control not to ravenously devour all the food placed before him. Manners had forced him to eat gingerly. Still, he had turned away nothing offered and left the earthen plates piled and empty where he sat. He had nodded along, listening to his host talk—and the old man certainly talked a lot.

Master Dawan, as he had rightly guessed, was a trader. He bartered everything from fine fabrics to oils, making at least two trips each long season across the desert. Nearby his tents, were at least four baushanga—great shaggy beasts larger than oxen with curving blue horns. They were slow and lumbering, but their hardiness made them the preferred pack animals of desert traders.

Now an elder man, Master Dawan claimed he had not spent his entire life in the desert. And that when he was as young as Makami, he had traversed far and wide, seeing and hearing of many wondrous things—from giant water serpents that lived beneath the seas, to creatures that were part men and part hyena, who roamed the scorched grasslands. Some things made Makami’s eyebrows rise, like the people who worshipped the many-handed god who it was said stood upon a great stool that rotated even as he spun, forever laughing at some great joke, which kept the world turning with him. Other stories however, like the one related to Master Dawan by a fellow trader, of lands beyond the known world, where white sand that was cold to the touch covered everything, and men with skin like a pig’s belly and adorned with golden hair draped themselves in thick furs, riding into battle covered in heavy metal and armed with broad steel blades, was simply too much to believe.

“And this is a feather from the great bird I spoke of,” Master Dawan said, “that lives high in the mountains of the East—so large it could snatch away a man.” He passed the giant grey feather speckled with bits of red to Makami. The thing was easily as long as he was tall. He ran a hand across the long soft fibers, feeling the hollow quill beneath.

“Ah, more tea?” Master Dawan offered. One of his daughters had come to pour more of the warm liquid into small rounded cups of polished stone at their feet.

Master Dawan had several daughters, six so far Makami had counted, and there was a seventh out at market. All were fairly young, ranging in ages close to nearing the cusp of womanhood. At least four wore two long braids that fell forward at the right sides their heads, red and black beads adorning them, while tinges of indigo stained their lips—signs among the desert people that each would soon be ready for marriage.

As the girl knelt in front of them, mixing goat milk into his tea, Makami smiled and nodded thanks. She only regarded him coolly behind dark eyes surrounded by lines of black ink. That was the usual response he received from each of Master Dawan’s daughters, who frowned or glared at him with open displeasure. It seemed they did not share their father’s charity to seeming beggars—but they held their tongues as well as their noses.

Like most desert people, Master Dawan’s daughters displayed a range of skin—varying from their father in either direction. The blessings of three wives, the old man had called them, all now gone—two lost to childbirth and one to the desert. Like her sisters this daughter was dressed in long robes of dark indigo that flowed down to her sandaled feet. Jewelry of crafted copper, silver and colorful stone adorned her everywhere, even tying into her lengthy braided hair. Most noticeable however were the markings. On her hands, arms, even her feet, were intricate designs and patterns etched in dark ink. The artistry was superb. But unlike his, these did not move. In all the fantastic tales Master Dawan had related, none came close to describing his curse.

“Beautiful yes?” the old man said, catching his gaze. “The work of my eldest daughter. She is quite gifted.” He paused. “So, then friend Anseh,” Master Dawan continued. “I have spoken at such length I have not heard your tales.

Makami took a deep sip from his tea. Anseh was his real name, from his people, the one he had been given. Whoever hunted him here, only knew Makami, the name he had taken for himself in these lands. After the past night, he had decided it was best he was Anseh once more.

“I am afraid my tales are not as grand, Master Dawan.” Makami did not flinch at his own lie. The horrors he had seen could compete with the best stories.

“Where do you come from then?” Master Dawan pressed. “You speak the trader’s tongue well, but your speech marks you as a man of the south.”

Makami nodded, impressed with the old man’s perceptiveness. “Far south, yes. But I have lived much of my life in the great cities of the west.”

“Ah!” the old man said with a knowing wink. “That explains your love of music! Some of the sweetest sounds to grace my ears have flowed from those lands.”

Makami nodded. “In the city of Jenna, I stood in attendance to the funeral of the late king. A hundred bards who played three-necked koras, a hundred drummers and a hundred more musicians and singers marched in procession as the king journeyed through the city, laid upon a bed of gold so heavy, that it was pulled by twenty stout war-bulls of purest white, their great horns too wrapped in sheets of gold. As he passed, the drummers struck their instruments in unison, while jombari players strummed gracefully, and the bards cried out so haunting a song, that the very sky opened and wept in mourning.”

Master Dawan listened, rapt by the tale. Sitting back, he released a breath of awe. Turning back to Makami, he looked him over with a wistful expression. “I say these words not as insult friend Anseh, but for one who has seen such wonders, you now seem overcome by misfortune.”

If it would not sound so bitter, Makami would have laughed aloud. Instead, he merely nodded.

“Well misfortune can be met with fortune,” Master Dawan said. “Soon, before the rains begin, my daughters and I will journey across the sands to the east lands. If it pleases you, join us.”

Makami looked at the man in surprise, taken aback.

“I can offer food and drink once more, but for so long a journey I shall expect you to work,” he said sternly, “—and listen to my tales.” At this he gave a smile and wink.

Makami smiled back. Perhaps his misfortune was easing, if only slightly. He opened his mouth to speak but was cut off as a sudden blur of feathers streaked past his vision. It was a bird—a large hawk. As Master Dawan held up a hand, it landed on a stretch of leather that covered the old man’s arm, extending its bright blue wings wide before folding them against its golden breast.

“Ah Izri!” Master Dawan greeted the bird brightly. “I trust you have brought my eldest daughter safely back from market.”

The way the old man spoke to the hawk, Makami half-expected it to answer. Instead it turned its gold crested head before again stretching its massive wings, taking off in a flapping blur and soaring straight towards an approaching figure.

Master Dawan clapped in delight. “Praise you Kahya! You have trained him well!”

The approaching figure didn’t answer immediately, dark piercing eyes passing over Master Dawan, and then Makami. A free hand moved to the dark veil which covered the figure’s face, pulling it down to reveal a surprising sight—a woman. Dressed as she was in dust-ridden flowing trousers and a billowing shirt, she was easily mistaken for a man.

“He is your bird father,” she said, thick black hair spilling down to her shoulders as she pushed back a hooded shawl. “I do not see why I must take him with me each morning.” With a series of clicks and whistles she lifted her arm and the hawk flew away, this time landing atop a wooden stand that stood beneath their covering. It perched there, gazing down at them.

“To watch over you dear Kahya. I trust Izri’s eyes as well as my own.”

The woman grunted and made a face, dropping down to sit cross-legged with them. “I handle myself well enough.” She poured herself some tea, sipping it slowly before turning a piercing gaze to Makami. “Another stray?” Her nose wrinkled with a grimace. “Can you at least choose one who wears more than rags and smells better than a wet baushanga?”

“Ah this is friend Anseh,” Master Dawan said, wincing slightly at his daughter’s sharp remarks, “a traveler who has fallen on ill fortune. I have offered him food and drink for work, from now through the crossing of the sands.” Makami opened his mouth to make his own introductions, but the woman abruptly turned away.

“That dog Zaba tried to trade me moth eaten cloths for near twice their worth,” she said, changing the subject. “But I bested him in the end. He parted with them for far less, and I received several jars of sweet oil as well—for nothing more than a few cones of salt. A worthy trade I think.”

Master Dawan nodded in appreciation, turning to Makami with a grin. “My daughter’s skills at haggling surpassed my own long ago.” He rose to his feet. “I will make the arrangements for Zaba’s goods. If you will, see to friend Anseh.”

Makami watched the old man walk away, leaving him with his eldest daughter. The woman continued to sip her tea slowly, as if he were not there. After a long awkward bout of silence, he opened his mouth to speak, but once again she beat him to it.

“Father is fond of strays,” she said, never looking to him. “Most do not last three days. Some less than two. It is the gift of free food and drink they are after, not true work. Stay on more than three days, and I will be impressed. Attempt to steal from us or take advantage of my father’s generosity, and I will send you back to the streets with less fingers than you arrived. Touch any of my sisters, and you will lose more than that.” Finishing her drink, she set the cup down and rose to her feet. “Now come, let us see if there is a way to rid you of that unbearable stench.”

As she began to walk away, Makami hurried to follow. He did not doubt the sincerity of the woman’s insults, or her threats. But fortune to him was rare in these times, and he was grateful for whatever form it took.

*

Three days passed. Then six. Then more than thrice that number. And Makami remained. The work was tiresome. He hauled heavy goods, combed the tangled mats from the baushanga’s thick fur, and toiled at varied tasks from morning until the sun set. It was the kind of work he had shunned in favor of a life as a skilled thief. But after all his recent troubles, there was something about the simplicity of it all that brought a brief moment of ease.

Master Dawan was true to his word, providing food and drink—and endless stories—for his labor. And he had provided clothing and as well as shelter. Makami now dressed in loose trousers and a long white shirt. He covered himself in the blue robes familiar to the desert people, and had even taken to donning the afiyah veil, especially concealing himself when they went into town. He did not allow himself to be lulled into complacency by this small reprieve. Somewhere out there, were men who hunted him for dark purposes. And as long as he had to remain here, he hoped to put them off his trail.

In fact, he had done a great deal to change his look. He had shaved his bushy hair, leaving his scalp bare—opting instead for a beard which he wished would hurry and grow thicker. Reliable meals and hard work had filled him out some, bringing back his slender but muscular body. Cleaned up, he looked a world apart from the vagrant that had first been brought to Master Dawan’s tents. And the old man’s daughters had taken notice. Now and then he caught them glancing at him as he worked, and whispering to each other before breaking into laughter. At first, he had thought he was the object of one of their jokes, until one of the young women had blushingly slipped a bracelet of threaded blue stones onto his wrist—a signal of courtship. He didn’t delude himself into thinking any of them actually thought of him as worthy of marriage; the daughters of even a poor trader could do much better. But he had proven himself at least attractive enough in their eyes to play in the game of mock courtship young Amazi indulged in.

Of course, he had hidden away the blue stones quickly. He did not want Master Dawan to believe he had any foul intent upon his daughters. And Kahya’s threats still lingered in his ears. If the eldest daughter was impressed at his having lasted so long, she never showed it. The most she ever spoke to him were new orders and work tasks, ignoring flatly any of his attempts at conversation. Still, the days among the trader and his daughters were the most peaceful he had known for some time. The nights, however, were another matter.

The markings on his chest never ceased their movements. And at night they seemed to become worse, a burning weight that lay upon him. They writhed about so furiously at times, he could not drift away to sleep. And when slumber did finally claim him, only terrible visions came. Some of them were from the past—like the angry drunk who had followed him after a night of gambling, intent on fighting or doing worse, torn apart by the winged monstrosity that had flown from within the strange markings. Or the cutthroats that had attempted to rob him, slashed to pieces by the claws of a beast he had unwittingly unleashed. And of course, Kesse was always there, sweet Kesse who he could not save from the evil that lived inside him. Other visions were of his fears, where vile things with dozens of legs and endless mouths crawled out of him like an army of insects, devouring Master Dawan and his daughters as they slept. Those dreams more than any sent him awake, and he would lay there, eyes wide open, waiting for the dawn

It was some twenty-eight days later that they finally picked up and began their trek into the vast, hot sands. With the baushanga laden with goods they set upon a path Master Dawan claimed had been used by the Amazi for generations beyond measure. Makami had never seen so much sand, like an endless ocean that Master Dawan aptly called the Desert Sea. He himself could discern no path. Each way looked much like the next. But the old man seemed to know his way, putting names to sand dunes, and tracking their movements by the sun in the day and the stars by night.

For Makami, his first few days had been spent suffering from what the old man called “sun sickness.” The relentless heat of the desert was unlike anything Makami had ever endured, and he had been forced to ride upon the back of a baushanga to keep from passing out. After a few days however, his endurance improved. And soon he was laboring under the scorching sun with surprising ease.

His days followed a familiar routine. He awoke to feed the baushanga, see to their needs, sat down to a meal with Master Dawan and his daughters and then helped pick up the tent to continue their trek. Most of his time he spent listening to Master Dawan recount endless tales. The old man seemed to always have something new, and never repeated himself. For a long while all seemed tranquil, until the storm.

Master Dawan claimed he had sensed it coming, and had ordered them to pitch their tents in a circle, placing the baushanga on the outside. Even as they tied down their dwellings the normally inert desert filled with a brisk wind that only grew fiercer with each passing moment. By the time night had fallen they were in the midst of a raging sand storm that blotted out even the moon, turning the already dark night into an impenetrable blackness.

Outside, his veil wrapped about him to ward off the stinging sand, Makami checked upon the slumbering baushanga. Stripped of their packs, they curled their great shaggy bodies into balls, hiding their heads from the winds and acting as a buffer against the storm. Still, Makami had to go out and check upon them several times, to make sure the beasts were still properly tied down. Master Dawan claimed baushanga had been known to wander off in the middle of sandstorms. Disoriented they could travel so far it would take days to find them again. Making certain their harnesses remained fastened about them he fed each a bit of pinkish fruit Master Dawan had said would keep them peacefully at rest. Barely lifting their heads against the sharp elements, they managed to down the fleshy fruit in noisy wet crunches between their block-like teeth.

Finishing his task, Makami picked up the oil lamp he had set beside him—the only light available in the thick sand-filled gloom. The winds were so strong he had to push hard against them, lest they knock him over. Stopping at his tent he lifted the lamp to look at the large symbol painted on the canvas. Smeared in goat’s blood, it was a ward against evil Master Dawan had insisted placed on all their tents. He claimed that storms often brought out demons that dwelled in the deep desert, things that crept up while you slept and drained all your blood or enticed men to wander from their dwellings to their deaths with haunting songs. Whether the old man was merely superstitious, Makami did not know. But he had accepted the ward all the same. He knew that monsters and demons were all too real.

Rubbing at his chest he walked into his tent, pushing close the flap behind him. Since the storm had begun, the markings on his chest had started to move about—much more than usual. It troubled him. He had long ago decided, were he to lose control again, he would abandon Master Dawan and his family and flee headlong into the desert, hoping to spare them from any danger. If it came to that, he would do so now, even in this storm. Better that than bring these good people harm.

Unveiling, he shook out sand from his afiyah before laying it flat upon the blankets he usually slept upon. He pulled off his shirt, dusting it off and throwing it to the ground. Standing there, with only the flickering lamp for light, he looked down to the arcs and lines which continued their odd movement across his skin. Putting a finger to them he traced their movements, as if touching them would somehow bring him insight. So, engrossed he soon became, that he did not notice the figure entering his tent until too late.

“I wanted to remind you to wake up early, before the dawn, to push away the sand from the baushanga—”

Makami turned in surprise, as Kahya strode through the flap he had left partially open. She carried a lamp and was wrapped in dark cloth. At sight of him she stopped speaking, her eyes going wide. With a silent curse beneath his breath he realized that he was still facing her, bare-chested and wearing only his flowing trousers. It took a moment—too long a moment—for his mind to tell his body to turn his back. And he knew immediately, she had seen. The lamp he had was small, but so was his tent, and it illuminated the space all too well.

“What is that?” he heard her ask breathlessly. Makami closed his eyes, cursing to himself deeply now, praying the woman would go away. Those thoughts were dashed as her hand touched upon his bare back.

“Stop jumping!” she admonished at his reaction. “Those markings on your skin—let me see!” When he did not respond, she released an indignant breath and pulled his shoulder hard, with more strength that he thought her capable. He turned to face her and she lifted her lamp to his chest, bending down to gaze at the markings in wonder.

“They move!” she breathed. Looking up to him, her dark eyes were wide. “How did you come by this? Did you make them yourself?”

“No,” Makami managed to answer. “This wasn’t my doing.” He released a sigh. “It would be too hard to explain.”

She gazed at him oddly, with a look that was different than her usual dismissive demeanor—as if only noticing him for the first time.

“And you can make them move,” she said.

“What?” he asked confused. “No, not me. They move on their own.”

Kahya wrinkled her brow. “Nonsense, the markings never move on their own.”

Setting her lamp upon the floor she turned her back to him. And then, to his surprise, began to disrobe. The dark cloth that covered her slipped past her shoulders, falling about her arms and her waist, revealing her bare back. Pushing her hair to the front, she tilted her head to him slightly.

“Watch,” she said.

Makami looked down to her back. A series of lengthy twisting marks covered its length like vines upon her dark skin. They looked much like the inked designs her sisters wore on their hands, with one remarkable difference. These markings moved.

He almost took a step back in shock, blinking to make certain he wasn’t seeing things. But no, the markings were moving. They didn’t circle and dance about like the ones on his chest, but they slithered about, seeming to grow and vanish only to reappear again, like thin serpents upon her skin. And then just like that, they went suddenly still. Finishing her display, the woman turned to him, holding her robes to her chest.

“You’ve never met anyone else with the gift?” she asked curiously. Makami stared at her perplexed. Gift?

She moved towards him, reaching a hand for his chest. He flinched slightly but did not pull back when her fingers touched the markings on his skin, slowly tracing their movements.

“I had thought I was the only one as well,” she said, “until I met another. She was a woman, older than me by perhaps a few seasons. She too had the gift. The markings she wore covered her whole body, even her face. And she too could make them move.”

“What is it?” Makami found himself asking. He looked down to his chest where her hand still lingered. “What are they?”

“Skin magic,” Kahya said. “That’s what the woman called it. She said only few were born to it, a magic woven into our very skin. Patterns like the ones we wear, marked into our skin, can bring that magic alive. I first learned of the gift when I was young. I thought my ability was to only make the art I worked into my skin move. She showed me however, that it could do more.”

“More?” Makami asked. His heart pounded. Could the answers he had sought have been right here all this time? Did the gods delight in teasing him so?

“It allows us to work magic.” The woman smiled slightly. “Sometimes I am able to create patterns that allow me to not feel the heat of the sun. Or heal a slight sickness. Or speak with my thoughts. Once I even managed to make water spring out of the sand. The woman said that with time I could learn to do even more—fantastic things. But I have no need for such power. I am kept satisfied by my small magics.” She looked up to him, those dark eyes probing. “What do yours do?”

Makami stiffened at the question. That answer was more than he was willing to give. Besides, he had another question.

“You made yours stop. How?”

“It is the skin that is magic,” she replied matter-of-factly. “Whatever patterns we place upon it are ours to control.” Seeing his blank expression, she frowned slightly and squinted with curiosity. “You truly don’t know?” He shook his head. Magic of the skin? He had never heard of anything like this.

“Fine then, I’ll show you.” Placing her palm flat against his chest she closed her eyes and exhaled deeply. “Breathe,” she told him. “Breathe like I do. Clear your thoughts of nothing but the markings, see them stilled, and breathe.”

Makami watched her for a while, attempting to emulate her actions. It took a few tries, but finally he matched her breathing, taking breath and releasing as she did so. Closing his eyes, he saw the markings in their normal dance, swirling about beneath his skin. He tried to see them stilled, imagining what they would feel like, finally at peace. It was a pleasant thought.

“Good,” Kahya said. “You learn quickly.”

Makami opened his eyes. He was readied to ask her what she meant, until his eyes fell to his chest. The markings had gone still. They sat there, unmoving, as if trapped in time. He gaped at them in wonder, a surge of happiness threatening to escape his mouth in a mad laughter. Looking to Kahya he saw a slight smile on her lips, as if amused by his own joy. He opened his mouth to thank her when a familiar feeling suddenly came. Gazing back down to his chest he found the markings moving again. They did so slowly at first, but soon built up speed, returning to their normal pace. His own smile vanished, at the loss of this minor triumph.

“Worry not,” Kahya told him soothingly. “You only need practice. Your magic is strong. It will be harder to control. If you like, I can teach you.”

He pulled his eyes from his chest, looking up to her. Teach him?

“Yes,” he nodded, unable to hide his eagerness. “I would like that. Please.”

Kahya lifted her shirt back to her shoulders, pulling it more firmly about her.

“Wait a while,” she said picking up her lamp as if preparing to go. “Then come to my tent.” Covering her face, she walked out into the howling storm, leaving him alone.

Makami did not waste time, hurriedly dressing. He had never wanted to learn a thing so much in his life. It was some time later that he found himself outside Kahya’s tent, a large one she reserved for herself. He stood hesitantly, uncertain if he should announce his entrance. In the midst of his thoughts her voice suddenly came, amazingly in his thoughts, telling him to enter. Doing as instructed, he pushed back the flaps and walked inside.

Master Dawan’s eldest daughter’s dwellings were at least twice the size of his own and more. It was filled with soft cloth and other strewn items. An iron brazier with red-hot coals kept the space warm, and provided the only illumination. A bowl of water was suspended above it, sending out steam to fill the tent in mist. Beyond the thick vapors there was a sweet scent in the air that tickled his nose. Of course, there was also Kahya.

The woman sat in a corner of her room, reclined upon several thick reams of red cloth. She had retired her usual billowy shirt and trousers, and now lay wrapped in light blue cloth that left her shoulders and most of her legs bare. Beads of water rolled down her bare skin, as the mist of the room clung to her. Leaning back, she held a long and ornately carved thin pipe in her hand, pulling from it and exhaling the sweet scent that filled his nostrils into the air. She lifted a hand, motioning for him to come closer. As he did so she looked up to him, her dark eyes tinged with red—an effect of the intoxicating herbal concoction he well recognized.

“You will need to be in your skin,” she told him.

Makami’s eye brows rose as he caught her meaning.

“Do not take all night,” she chided.

Following her commands, he pulled off his shirt and then his trousers.

“Come,” she said, patting the space before her. “You will have to learn it the way I did.”

As he knelt down, she discarded the cloth that hugged her, urging him forward. In moments the two sat touching, their sweat-slick skin pressed against each other. It was a soothing warmth, one that Makami had come to forget. Meeting his gaze, she parted her lips, blowing thick smoke upon his face, directly into his nostrils. He coughed but inhaled, feeling the sweet vapors enter his mind.

“Now breathe,” she told him, her heaving chest pressed against his own, arms now clasped around his back. “Breathe in time to me.” He took a deep breath, following her lead. On his chest, he knew the markings were still moving but slower. He could feel them.

“That’s it,” she whispered, her breath warm in his ear. “Breathe. Just breathe.”

Makami found himself matching her rhythm now, drawing and releasing breath. And he did so as long as she urged him. It was well into the late hours of the morning that he drifted off. But when he did, the markings on his chest had ceased moving. And for the first time in what seemed a lifetime, his dreams were not nightmares and he slept in peace.

* * *

“Three men. And they come swiftly.”

Makami took the looking glass from Master Dawan, peering through. It made the objects that appeared as mere dots against the sand in the distance seem close enough to touch. They were three men, their faces veiled. Each rode upon their own mjaasi—a giant sand lizard that could travel the desert at vast speed, and required little water.

“Blue men?” he asked.

Master Dawan shook his head. “Blue men would not so easily announce their coming.”

Blue men, or the Taraga, were strange desert people—some say a lost branch of the Amazi. None knew much of them, except that they dressed in robes of deepest blue, and even covered their skin in the rich dye. They often raided caravans, carrying off goods and people—mostly women, children and young men. Those who had survived their attacks claimed the Blue men merely appeared, as if out of nothingness, and then vanished just as quickly.

“Whoever they are, they’ve spotted us, and are riding hard in our direction.” Kahya had taken the looking glass and now peered through it as she spoke. “We can’t outrun them. Stop the baushanga. I’d rather we met these strange men with our faces than our backs.”

Makami nodded. The woman did not even look back at him before she turned to converse with her sisters. It had been some eleven days now since their encounter during the storm. Since then he had shared her tent each night, and they had held each other, as she taught him this skin magic—and how to control the markings upon him. On those nights she was a different person, adventurous, daring—even playful. But in the open day she was just the serious-minded daughter of a trader, and treated him as she always had. He did not think Master Dawan or her sisters knew of their secret meetings. Both had been quite discreet about that.

Moving off to the baushanga, he pulled on their reins, making the clicking noises of reassurance to stop them. Looking into the distance he could make out the three approaching figures much better now, without the need of the looking glass. They would be upon them in moments.

“Friend Anseh.” He turned to find Master Dawan standing nearby. “I do not know these men, and every precaution is necessary. I will speak to them in peace, but if that does not work...” The old man reached into his robes and drew out a knife. “Can you use this?”

Makami took hold of the weapon, noting the intricate golden hilt and the sharp gleaming curved blade. With dexterous agility, he twirled it across his hand, unsheathing it in a swift display, causing Master Dawan’s eyes to widen slightly.

“I see then that you can,” the old man said, a bit of excitement in his voice. Makami had a feeling he would one day be asking to hear the tale of how he had learned that ability.

“Here they come,” Kahya declared, coming to stand beside them.

Makami looked up to see the three men riding down a dune directly in front of them. The brown and white-striped mjaasi they rode kicked up billowing puffs of sand as they more scampered than ran, their clawed feet barely touching the ground. They brought their riders just up to the caravan, stopping short when the leather reins tied to their necks were pulled. The baushanga shifted slightly at sight of the creatures, eyeing them warily, their normally blue horns changing to a dull orange—a clear warning. Despite their size, mjaasi had small teeth. Exceedingly sharp and numerous, they were better suited for devouring rodents and would not fare well against the tough hide of a baushanga. But the pack beasts didn’t take chances, and would charge with their great horns if these strangers came too close.

“Manhada,” Master Dawan said, palming his forehead in greeting. “The goddess smile on you with good fortune.”

The three men did not respond right away, shifting their gaze down to the old man and his caravans. Each was wrapped in dark fabrics that enveloped them completely. With their veiled faces all that could be discerned were their eyes which were unreadable. But there was something odd about the way they sat, so casually upon their steeds, showing none of the caution anyone would at meeting strangers out in the deep desert.

Finally, one of them, the one whose steed stood closest, began to unwrap his veil. In moments his face was visible, that of a man—the flints of gray in his beard showing he was older certainly than Makami, but younger still than Master Dawan. His broad frame was visible beneath his clothing, matching his large hands. He stared at them all a while longer, his dark eyes piercing. Then quite unexpectedly a bright grin of white teeth crossed his ebon skin.

“Manhada,” he replied back in greeting, his voice a deep baritone. Palming his own head, where only a strip of hair grew in the middle, he nodded slightly. Makami took note of the man’s accent. He knew the customs of the desert people well enough, but he did not share their dialect. He spoke trader’s tongue impeccably, like someone who was well-traveled. “May the goddess smile upon us all. May she smile on you even more, if you so happen to have water.”

Master Dawan motioned to one of his daughters who stepped forward. Gingerly, she offered up a leather pouch filled with water. The man looked down from his mount, his smile unwavering. Reaching down he took hold of the pouch and paused. Makami’s hands tensed on his knife, anticipating trouble. But the man only took the pouch with a solemn nod. In moments he was downing its contents, much of it running down his beard and soaking his clothing. His thirst quenched, he tossed what was left to one of his companions, who caught it and began to drink just as heartily.

“Many thanks,” the man said, wiping his mouth with the back of his hand. “I thought we would die with sand in our throats this day.”

“The sands do not show mercy,” Master Dawan remarked. “What finds you so deep in the desert friend?”

“My men and I were guarding a caravan. But we lost them in a storm.”

“A fierce thing,” Master Dawan noted. “It passed over us some nights past.”

“Most likely one in the same,” the man grunted. “We have not been able to find them since. I fear them perished—as were we until we spied you in the distance. My men and I are hungry, thirsty. Our mounts need feeding as well. If you could spare a bit more to drink, to eat, before we set out—”

“What can you offer in trade?” It was Kahya that spoke. She had donned her veil once more, her muffled voice and clothing making it hard to discern if she were man or woman. Makami knew she had spoken quickly, lest her father in his generosity offer away the little supplies they held for nothing.

The man smiled knowingly. Reaching into his robes he took a small pouch and tossed it over. Kahya caught it nimbly, snatching it from the air and opening it, peering inside. Gold dust, Makami could see.

“A week’s earnings,” the man said. “More than enough I hope.”

Kahya nodded curtly. The gold dust would resupply them and more at the next trading village.

“I am Master Dawan,” the old man said warmly, now that such matters were finalized. “And I offer you food and drink friend....?”

“Abrafo,” the man answered.

“So, it is then, friend Abrafo,” Master Dawan said. “Night draws near, you may camp with us and we will share food, drink and tales.”

The man Abrafo gazed down, smiling widely, as if that was what he had been waiting to hear.

It was well into dusk, as the sun lowered in the horizon, taking with it the last shafts of light in the desert that the caravan and their new guests sat in a circle about a fire eating, drinking and talking. Master Dawan’s daughters had slain a goat, preparing enough food for them all, and they sated their bellies. A few of the young women even danced, showing skills at balancing knives and swords atop their heads as they twirled to a rhythm beat upon a flat drum by their father who chanted some unknown song in the Amazi tongue.

The big man, Abrafo, seemed to delight at this, clapping heartily as he ate, and listening riveted to the tales Master Dawan eagerly spun. Makami sat back, eating his own food slowly, but saying little. The other two strangers—muscular men with rough faces named Cha and Kadori— said even less. Their stone demeanor betrayed nothing but seemed to take in everything at once.

Something about them did not set right with Makami. More than once he thought they glanced in his direction. But they had looked away so quickly, he began to wonder if it wasn’t his own mind playing tricks. Still despite this seeming calm, he kept his eyes open, the knife Master Dawan had given him tucked away safely beneath his shirt. He hoped he would have no need of it. Kahya did not eat with them, taking her food inside her tent where she claimed to be handling business. In all this time Makami had only seen her a few moments, still veiled and not even looking his way. He wondered to himself if tonight, they would still be able to have one of their lessons.

“You are blessed with beautiful daughters and fabulous tales Master Dawan,” Abrafo was saying, his rumbling voice filled with mirth as he drank from a wooden bowl. The skin on his powerfully built arms glistened in the fire’s glow. Since settling down the three men had discarded their lengthy cloaks, revealing long loose-fitting trousers and dark shirts. All had weapons strapped to them. Nothing alarming for caravan sentries, but still—it made them seem like leopards.

“Friend Abrafo, you are too kind,” the old man said, graciously accepting the compliment. “But surely, in your work, you have tales to share as well?”

The big man laughed to himself, sipping again from his cup. He cast a glance to his men, who glanced back. It was such a swift thing that most would not have noticed. But Makami was keeping his eyes on them. In his homeland he had seen leopards hunt often as a child. And they too had a silent way of speaking.

“Tales I have in great number,” Abrafo said finally. He settled back lazily on one elbow; the cup held before him while a wistful expression stole his face. “Here is one you may find of interest—it is about a thief and a sorcerer.”

Makami stopped the cup that he was lifting to his own lips, his ears perking to life. Staring at Abrafo the big man did not seem to be looking in his direction, but his words had set Makami’s heart fluttering.

“There was once a thief,” the big man said, “who lived in a city to the far west, in one of the great kingdoms, between oceans of water and oceans of sand. He was a good thief, whose fame was celebrated on the streets of the city for his daring thefts. One night he decided to increase his fame. He would steal a prized jewel from one of the richest men in the city. What the thief didn’t know was that this man was a sorcerer, and not a man of simple magics or one who you go to for healing. No, this man practiced dark magics, forbidden in the kingdom. He belonged to a secret brotherhood, and they had become quite wealthy dabbling in their terrible practice.”

Makami’s heart beat so fast now that he thought it might jump from his chest. And for the first time, in some eleven days, the markings on his chest began to move. Since his first lesson with Kahya he had been able to control them, keeping them still while he slept and, in the days, while he worked. But his breathing had become sharp and chaotic listening to the big man’s tale, and what control he had slipped away. This tale was becoming too frightening, too real.

“That very night,” Abrafo went on, “the sorcerer was working one of his greatest magics—markings etched with blood and ink upon stone. Unknown to him however, a thief had entered his home. The two stumbled upon each other, quite in surprise—the thief thinking that the darkened home was empty, not expecting to find anyone within. Any other day, the sorcerer would have killed an intruder outright. But the magic he dealt in was powerful, and required all his concentration. In that moment of distraction, the sorcerer was seized by the very forces he sought to control and pitched forward—dead.”

“And what of the thief?” Master Dawan asked, his eyes alive with intrigue.

“Well that is where the story gets interesting,” Abrafo said with a wink. “The sorcerer died, but his magic did not. You see the thief himself could wield magic—a deep and old magic that rested within his skin. And magic, good or ill, is attracted to magic—it seeks it out, is drawn to it. The dark magics of the sorcerer came alive at sensing him. They left the stone they had been etched upon, latching onto this thief, burying into him, marking his skin.”

Makami glared openly. So, this man knew his story, knew it in detail that no one else could, and now gave answers that he himself could only have guessed upon. He still remembered that terrible night, standing with the dead sorcerer at his feet, watching as the strange markings etched onto the ground had slithered across stone, seeping into his skin, crawling up his body and embedding into his chest. The pain had been so great, he had almost passed out. Only fear had kept him awake long enough, to flee into the night and back home....

“But the unlucky thief didn’t know what had happened to him,” Abrafo continued. “You see the sorcerer had been creating doors with those markings, symbols that opened pathways to other worlds where unknown things dwell—demons and dark spirits. The unsuspecting thief returned home; this wicked magic buried into his skin. And there he fell into a deep sleep. But the magic worked upon him yet stirred. That very night as he slept, the markings upon his chest opened a door, releasing a monstrous demon that killed his wife, who herself was with child. When he awakened the room, he slept in was covered in her blood. Some say the thief went mad that night, and fled the city, forever running from the monster he had become.”

Makami released a sob, the tears he had tried to hold back choking him. Images of sweet Kesse flashed through his mind, and the events of that terrible night. The man knew much, more than Makami ever did—but not everything. He had not awakened to find Kesse dead; he had awakened to see it happen. He had watched as the terrible thing with endless arms, bristling with black hair, had emerged from his chest. He had watched it grab onto Kesse, and seen her wide terrified eyes as the monster ripped her to pieces. And he had been too weak to stop any of it. He had indeed gone a bit mad that night. But if these men still sought him, knowing all they did, they were madder than he.

“What do you want?” he asked, his voice matching the resignation on his face.

The big man Abrafo slowly finished draining his cup before turning to Makami, a slow smile spreading across his face. “So, the thief finally speaks.”

Makami did not reply. Casting eyes to the two other men, he could see they now stared at him openly. No, it had not been his imagination after all. Leopards these men were—and eager to hunt. Turning back to their leader he released a weary sigh.

“Whatever you want, whatever you think you’ll get from me—there will only be death in the end. You have come all this way, for nothing. Go now, please.”

Abrafo only returned a wider smile. Master Dawan frowned deeply, looking from Makami to their new guests in puzzlement, trying to fit the pieces together in his head. The old man may not have yet understood what was going on, but he could certainly sense the dangerous tension that now filled the night air.

“It is not about what we want friend thief,” Abrafo replied calmly. “Your fate is not ours to decide.” He paused. “Take him.”

At least that’s what Makami imagined had been said, because the big man spoke his last words in an unfamiliar tongue. But his leopards pounced at his command. They were upon him so quickly there was barely time to react. Strong hands grabbed and wrestled him to his knees. The knife he had held was twisted from him, skittering onto the sand, as a longer sharper blade was placed to his neck. About him Master Dawan’s cries of protest mingled with his daughters screams. Then suddenly, there was a cry of pain.

Makami looked from the side of his vision to see Kahya, unveiled and wielding her large blade. The commotion had drawn the woman from the tent and she had emerged, weapon at the ready. One of the men that had held him down clutched at his arm, cursing at the blood that seeped through his clothing. Kahya moved towards him again, deadly intent her eyes. But the leopard was faster. He slid out of her way, and with his good arm caught her by the wrist, wrenching it cruelly until she cried out and released her grip. A quick blow to the woman’s side seemed to take her breath, and she doubled over in agony, the fight momentarily gone from her.

“There’s no time for this,” Abrafo growled in annoyance. He grabbed Kahya, tossing her towards her family and drawing a large sword with a jagged end which he held menacingly. “As we planned! Hurry!”

Makami watched the chaos about him unfold, lost in a void of pain. The markings on his chest had begun to move long ago, rising with his own fear, and they burned with an intensity that threatened to overwhelm him. He barely noticed as his shirt was ripped away, or when a hand touched his chest, slathering on something cold and liquid. And then, quite unexpectedly, the pain diminished. It ebbed away, all but vanishing. Soon, he could feel nothing at all.

Makami looked down to his chest in surprise, to where two strange markings in red had been freshly painted, still dripping from him like cold blood. Whatever the symbols were, they numbed his skin, making it feel as if cold needles were prickling him. The markings on his chest slowed their rhythm and then went still.

“Good then,” Abrafo said, his toothy smile returning. He looked down to Makami and winked. “You see, we have our magics as well. Weak yes, but enough to keep us all safe.”

Makami stared at his chest, dumbfounded. Looking back to his captors he glared at them. Men who not only hunted him, but who knew how to subdue him. These leopards had been well-prepared.

“Who are you?” he asked behind clenched teeth. “How do you know about me?”

“We are couriers,” Abrafo replied plainly. “Sent to retrieve and deliver you.”

“Deliver me? To who? Who do you work for?”

Abrafo walked over, bending down to his haunches to meet Makami’s gaze. “The sorcerer who you came upon that night, belonged to a secret brotherhood.” He pulled forth a strip of red cloth tucked into his shirt, opening it for all to see. Upon it in black ink was printed the dismembered hand of a great cat, its claws ready to strike. “They call themselves the The Leopard’s Paw. The sorcerer who died was one of the most powerful among them, and his brothers have been unable to recreate the magic he worked that night. But why recreate, when you can merely steal...eh, thief?” The big man laughed at his own wit.

“They want this.” He pointed to the markings on Makami’s chest. “And they have sent us to find you. Or rather a courier was sent to hire us—the The Leopard’s Paw never shows its true face. The brotherhood could sense you and offer guidance in our hunt...but only when the markings were moving, or when a doorway opened, when the magic was at its strongest.”

“It flared greatly in the trading town you spent time in, about the same time I mysteriously lost three men I had ordered to search for you. You would not happen to know of them?” Makami winced slightly and Abrafo’s smiled widened. “No matter, greed is often the end of fools. But by the time I arrived you had gone into the desert. We followed, only to have the trail end. The brotherhood was unable to sense you, as if the markings had gone silent.” Makami said nothing. Kahya’s tutelage had unwittingly spared him for some time. If only he had known all of this earlier, how much more lives could have been saved.

“But I know little of magics,” Abrafo shrugged. “My business was to find you, with or without the brotherhood’s help. We must have gone through near a score of caravans in this cursed desert, searching for you, killing and taking food and water as we needed, leaving no sign of our passing. But the goddess of the Amazi must have smiled upon us with good fortune today.” He turned to Master Dawan and his family, who remained huddled together, fear painted on their faces. All except Kahya, who knelt before her father and sisters protectively, her dark eyes glinting steel. A pang of regret washed over Makami as he thought of the danger he had brought them.

“These sorcerers,” he said. “They can remove these markings from me then?”

Abrafo laughed, glancing to his companions who responded in kind. “Remove them? Oh yes. That is their intent. My men and I have a wager on how the brotherhood will claim the markings. They think the sorcerers will cut out your chest and mount it on a wall, from where they can call their dark spirits. But I believe they will peel the skin from you, and perhaps wear it over their own flesh.” Makami stared at the man aghast. “As I have said, I know little of magics. But the courier explained to us that the markings and your skin had become one—which is why the brotherhood needs you brought back to them. Whoever controls your skin will hold power over the markings and the dark beings they call forth. You carry with you a weapon thief, which they intend to wield.”

“A weapon?” It was Kahya that spoke, her eyes now wide in alarm. “And you would hand it over so willingly? If these markings hold such power as you say, do you not worry to what purpose these sorcerers will put it?”

Abrafo shrugged. “Perhaps they will wield it against their enemies. Or perhaps they will unleash horror upon the lands. It is not my concern or care. So long as I receive payment.”

“Friend Abrafo.” It was Master Dawan now who spoke, his voice gentle. “Certainly, there are greater things in this world than wealth. What these dark men of foul magics would do to this man, what they would do with this power, surely it must weigh upon your heart.”

“Wealth?” The big man laughed. “You mistake us Master Dawan. Wealth is not what the sorcerers have promised us for this prize.” He moved to kneel and look the old man directly in the eye. “We are to be gifted with magics that will make our skin invulnerable to weapons, our blood immune to poisons, bodies able to heal from any wound or affliction. We will be immortal. Whatever may come, we will survive it—and then we can become as rich as we wish.” He came to his feet and released a lengthy breath. “But for now, Master Dawan, there will be some unpleasantness to come, for your eyes and ears have witnessed much—and the brotherhood greatly values its secrecy.”

As the grim meaning of those words sank in Makami felt his stomach go hollow. A look of horror crossed Master Dawan’s face as he reflexively reached for his daughters. Then just as quickly, he returned to his jovial self.

“Come then friend Abrafo,” he urged pleasantly. “There is no need for such talk. Surely, we can arrive at some understanding. My family and I are but simple traders. We spend much of our lives in the desert. Who can we tell such tales to?”

“Ah, Master Dawan,” the big man smiled, wagging a finger playfully. “But you are a lover of tales. And this story may be too great to keep. No, there is no understanding to which we will come.”

The pleasantness on the old man’s face slowly slid away, and Makami felt his stomach tightening. Abrafo sounded like a man who would regret the slitting of a child’s throat, but slit it all the same.

“Please, I beg you. If you must silence any tongues this day, let it be mine.”

Master Dawan’s daughters screamed as one at his words, clutching and pulling at their father as if he had already gone. Even Kahya looked stunned, her face trembling.

Abrafo stared at the old man, seeming to mull over his words before shaking his head.

“No, I cannot grant that wish Master Dawan,” he said finally. “But you offered me food and drink, and for that I am grateful. So, I will promise that at the least, you will not have to watch your daughters die.” He gave an order and one of the other men grabbed the old man, pulling him away from his family who wailed and tore at his clothing. Kahya rose up, as if she intended to fight all three of their captors with her bare hands alone. But Abrafo caught and easily wrestled her to the ground, bringing his jagged sword to the throat of a younger daughter in threat. Master Dawan was brought to the forefront, and placed upon his knees. His eyes were closed and his mouth moved rapidly, speaking words in his native tongue. A prayer, Makami knew. It came like a song that rose and fell in a rolling fashion.

“Yes, old man,” Abrafo said soothingly. “Finish the prayer to your goddess. You will be reunited with your daughters soon enough.”

Makami watched the unfolding scene in horror. The knife at his neck had been pressed so firmly into his skin that it now drew blood. Catching a glance of Kahya he met her eyes to find she was staring directly at him, her gaze stabbing into him and her mouth moving. At first, he thought the woman was praying as well. But no, she was saying something, directly to him, shouting it in fact, above the screams of her sisters and her father’s sorrowful entreaties. Breathe, she was saying. Breathe. Breathe. Breathe.

Makami listened puzzled as she repeated the words, almost pleadingly. He had heard them before, whispered into his ear during their nightly sessions, as they lay wrapped in each other’s skin. It was how she taught him to slow the markings, to control his skin. He was struck suddenly by his own thoughts, mingling with the words Abrafo had spoken earlier. Control his skin. The markings as a weapon. Whoever wielded it...

He met Kahya’s eyes with sudden understanding, and attempted to do as she asked—breathe.

It took some trying, the chaos about him distracting his thoughts. He had to find a way to concentrate. It came amazingly from Master Dawan. The old man’s prayerful chant flowed into his ears, offering him the bit of peace he needed. The markings shifted upon his chest—only slightly, but enough to give him renewed hope. He did not dwell on the irony that the very curse that had robbed him of so much, might now offer salvation. It is the skin that is magic. That was what Kahya had taught him. Whatever was placed upon it was his to master. Yet, try as he might, the numbness on his skin robbed him of control. It was like trying to move a boulder. But wait . . . something else moved.

Yes! It was the other markings, the ones just placed upon him. Abrafoa had called them weak magic, and they moved easily. In short moments he made quick work of one, shifting his skin until it broke and peeled away. Sensation returned quickly to his chest again, and his own markings began their familiar dance. Concentrating he worked upon the second symbol. It twisted and then gave, untying like a knot undone and dripping away. And then there was pain. Terrible pain flooded his body as the markings on his chest swirled about furiously. The lines and arcs began to fit into each other, falling into place, creating a symbol before going still. He braced for what he knew would come next.

Makami heard his own screams as fire erupted from his chest. He did not seem to burn, but the heat was more intense than anything he had ever felt. The thing that emerged from him was shrouded in flames, and he imagined that whatever place it came from was an endless inferno. Its massive bulk towered into the night, like a flaming beacon in the darkness. Unknown symbols like writing adorned the skin of its pale and reddish muscled body which slightly resembled that of a man. Its head had no face or features of any kind, only a crown of endless horns. Where forearms should have been, its arms extended into two large blades of bone that glistened like steel.

By now, Master Dawan’s prayers had ended, and all had gone silent, bearing witness in awe to the nightmare before them. The first person Makami heard speak was the man who stood over him. It was a whispered prayer as the great being swiveled a horned head to look down at them with its eyeless face. It raised one of its arms and there was a blur as the great blade came down swiftly. Makami felt the knife at his throat fall away, along with the half of his captor that held it. The man had been sliced in two, the heated blade from the being cauterizing the wound so well that no blood splattered.

At sight of his companion’s demise, another of the men cried in fear and made as if to run. There was another blur of the creature’s arm came down, this time cutting cleanly in one stroke from head to crotch, impacting heavily against the sand which was sent up in a billowing cloud. It shifted its horned head then to Abrafo.

The big man stared up at the behemoth that dwarfed him, his sword hanging limply at his side. He turned to Makami, a look of absolute wonder in his eyes. Then, as a familiar smile crept across his rapt face, he uttered one word.

“Magnificent!”

It was his last, before the great being lifted a thick flaming leg, looking somewhat like an elephant’s only ten times as big, and brought it down, crushing the man beneath tons of flesh and flames. It stood there for a moment, seeming to exult in its kills. And then it turned that horned and faceless head to those that remained.

Master Dawan had long ago scrambled towards his family, and now spread his arms protectively against his daughters, as if that could possibly shield them. The great being gazed down at them hungrily, lifting its blade with murderous intent.

“No!” Makami was surprised that the cry came from his weakened lips. He was even more amazed when the great being turned to stare at him, with its odd eyeless gaze. Whoever wields the magic . . . he recalled.

“It is the skin that is magic. And as the markings are drawn onto my skin, I hold power over them—I hold power over you.” The great being reared up—the flames that shrouded it flaring in anger. It stalked forward, in two giant steps coming to tower above him. Makami could feel its terrible heat fierce upon his skin, but he continued. “I hold power over you! And I command, you leave them unharmed!” Makami knew his words would have sounded stronger if he was more certain, and they didn’t come in ragged breaths. He was not sure what he expected to happen next. This monster could kill them all.