In December 1812 the majority of the Young Guard regiments that had served in Russia existed on paper only, having succumbed to the various battles, such as Krasnyi, and the Russian winter. The Russian Army had also suffered badly; for example, by early January 1813 the five regiments that formed the 13th Infantry Division – including the 13th and 14th Jaeger Regiments – together numbered only 1,091 (Beskrovnogo 1956: V.22). Kutuzov argued that the Russian Army should wait before it advanced into Germany, but Tsar Alexander was impatient; he did not want Napoleon to be able to recoup his losses, so he ordered the Russian Army to continue its pursuit of the Grande Armée. It would be Alexander’s enthusiasm in the forthcoming campaigns that would eventually lead to Napoleon’s defeat in 1814.

Meeting of Friedrich Wilhelm III of Prussia (left) and Alexander I of Russia on 13 March 1813, by Woldemar Friedrich. The entry of Prussia into the war against the French was a vital element in the transformation of Alexander’s bid to defeat Napoleon from personal grudge to genuine coalition warfare. (RC)

The Russians scored an early success on 7 February 1813 when they occupied Warsaw. However, the Tsar needed allies if he was to accomplish his aim of liberating Europe. The Prussians declared war on Napoleon on 13 March 1813, eager to revenge their defeat in 1806 and humiliation at Tilsit the following year. This might not have proved disastrous for Napoleon, because he had fought a war against Prussia and Russia before and won. However, the 1812 campaign had cost Napoleon the lives of many of his veterans. True, his regiments had suffered casualties in previous campaigns, but nothing on this scale – and there had always been sufficient veterans left as a nucleus around which the units could be rebuilt. Furthermore, there had always been a period of peace after a campaign in which he could train the recruits to the standard expected in the Grande Armée. Now, in 1813, the recruits had to be trained on the march to join the field army, rather than at the regimental depots.

Major-General Maxim Constantinovich Kryzhanovsky (1777–1839) was the commander of the Finland Guards Regiment from its inception as the Imperial Militia Battalion in 1807 until 1816. He fought at Borodino, Krasnyi, Lützen, Bautzen and Kulm, before being gravely wounded at Leipzig. (AM)

Napoleon also recalled regiments from Spain and cleared the depots of the Young Guard and line regiments and so was able to rebuild his army, which outnumbered the combined Russo-Prussian Army. However by weakening the army in Spain, this took some of the pressure off Wellington’s and the Spanish Armies. In addition to the loss of men was the loss of horses for the cavalry, which could not be so easily replaced. It would be a lack of cavalry that would hinder Napoleon in the forthcoming campaign. Reinforcements were also on their way to the Russian Army, but they would take time to cover the vast distances between their initial rendezvous and the main army; by mid-April 1813 the Russian II Infantry Corps only numbered 6,109 officers and men, while the IV Infantry Corps had just 2,990 all ranks (Beskrovnogo 1956: V.514–15).

The struggle for Germany started well for the Allies when they defeated the French at Möckern (5 April 1813), but on 28 April Kutuzov died. He was replaced by General of Cavalry Peter Wittgenstein, who although less capable than other senior Russian officers was the most popular choice, having protected St Petersburg from MacDonald’s X Corps and Oudinot’s II Corps in 1812.

Général de division Pierre Dumoustier’s Young Guard Division, which had mustered 11,670 combatants on 25 April, was heavily involved in the fierce fighting at Lützen (2 May), a victory for Napoleon; it suffered 1,069 casualties, including Colonel-Major Jean-Paul-Adam Schramm, commanding officer of the 2nd Voltigeurs, and both majors of the 1st Voltigeurs (Lachouque & Brown 1997: 294). According to Chef de Bataillon Felix Deblais of the 1st Tirailleurs, ‘All the Young Guard did marvels’, and Joseph Duffraisne of the Fusiliers-Grenadiers recorded, ‘It was the Voltigeurs of the Guard who won this battle. They lost many men, up to fifty or sixty per company’ (quoted in Uffindell 2007: 94). By 5 May Dumoustier’s Division mustered 7,865 combatants; a further 3,040 were in hospital, although only 10 per cent of these were battle casualties, ‘a strategic consumption loss of approximately 25 percent from April 25 to May 5’ (Bowden 1990: 90).

The Russian Lifeguards were also present at Lützen, and also the subsequent battle of Bautzen (20–21 May), another French success; because of the gallant conduct of his Finland Guards Regiment at Bautzen, Colonel Maxim Constantinovich Kryzhanovsky was promoted to major-general, while his battalion commanders and lesser officers received bravery awards, along with five other ranks in each company (Gulevich 1906: 290). Both Lützen and Bautzen could have been decisive victories for Napoleon, but his lack of cavalry had prevented his army routing the Allied forces and they were able to withdraw in good order.

General of Infantry Mikhail Bogdanovich Barclay de Tolly (1757–1818). One of Russia’s best senior commanders, Barclay de Tolly served in a succession of Jaeger units in the 1790s before distinguishing himself in the campaigns of 1806–07 and then against the Swedes in Finland in 1808–09. His caution in 1812 – and his German–Scottish ancestry – made him many enemies in the Russian high command, but his proven abilities saw him return to senior command in May 1813. (RC)

On 18 May the Swedes – under Napoleon’s former maréchal, Jean-Baptiste-Jules Bernadotte, now the Crown Prince of Sweden – landed in Pomerania on the Allies’ side. On 26 May Wittgenstein was replaced by General of Infantry Mikhail Barclay de Tolly. It had been Barclay de Tolly’s strategy of retreating into the heart of Russia which – although it had been extremely unpopular – had reduced the strength of Napoleon’s Grande Armée. On the same day another clash came at Haynau, but despite the French being defeated, the Allies fell back into the Prussian province of Silesia.

By now both sides were exhausted. Napoleon had made approaches for a ceasefire before the battle of Bautzen, but these had been rejected by Alexander. Now, with Austrian mediation, both sides agreed to an armistice on 4 June, which would last until 16 August. This gave both sides time to recover before the resumption of the campaign. During this period reinforcements arrived to reinforce the Finland Guards Regiment; one 463-strong contingent included Pamfil Nazarov, who had finished his training. This brought the regiment up to about 1,400 strong and so it was able to be formed into three battalions once more (Gulevich 1906: 291). The Grande Armée was also able to increase its strength; by 15 August the 1st to 4th Young Guard Infantry Divisions mustered 8,590, 8,186, 8,037 and 7,894 officers and men respectively (Bowden 1990: 126).

During this armistice the Austrians signed the Treaty of Reichenbach on 27 June, which would lead to Austria declaring war on Napoleon on 12 August. It was decided that each of the main Allied armies would be a mixture of nationalistics. The Army of Bohemia was to be commanded by the Austrian Feldmarschall Karl Philipp, Fürst zu Schwarzenberg; the Army of the North was led by the Crown Prince of Sweden, while the elderly Prussian General der Kavallerie Gebhard Leberecht von Blücher was to command the Army of Silesia. The Allies agreed to the Trachenberg Plan (15 August), which aimed to defeat Napoleon’s maréchaux one by one, before confronting Napoleon himself. If one of the armies was threatened by Napoleon, then it would retreat, allowing the other two armies to take the initiative.

With the resumption of hostilities this plan worked well, with a string of Allied victories at Großbeeren (23 August), Katzbach (26 August), Hagelberg (27 August), Nollendorf (29–30 August), Kulm (29–30 August), Dennewitz (6 September) and Wartenberg (3 October). True, Schwarzenberg was defeated by Napoleon at Dresden (26–27 August) – where the Young Guard saw action, as well as the Finland Guards Regiment – but slowly Napoleon was being ground down. Moreover, once-loyal allies of the Emperor changed sides; Bavaria, which had been France’s ally for centuries, joined the Allies on 8 October, so weakening Napoleon further. Finally the Allies felt strong enough to confront Napoleon at Leipzig. The ensuing battle would be the largest until World War I and a decisive turning point in the struggle between Napoleon and his enemies.

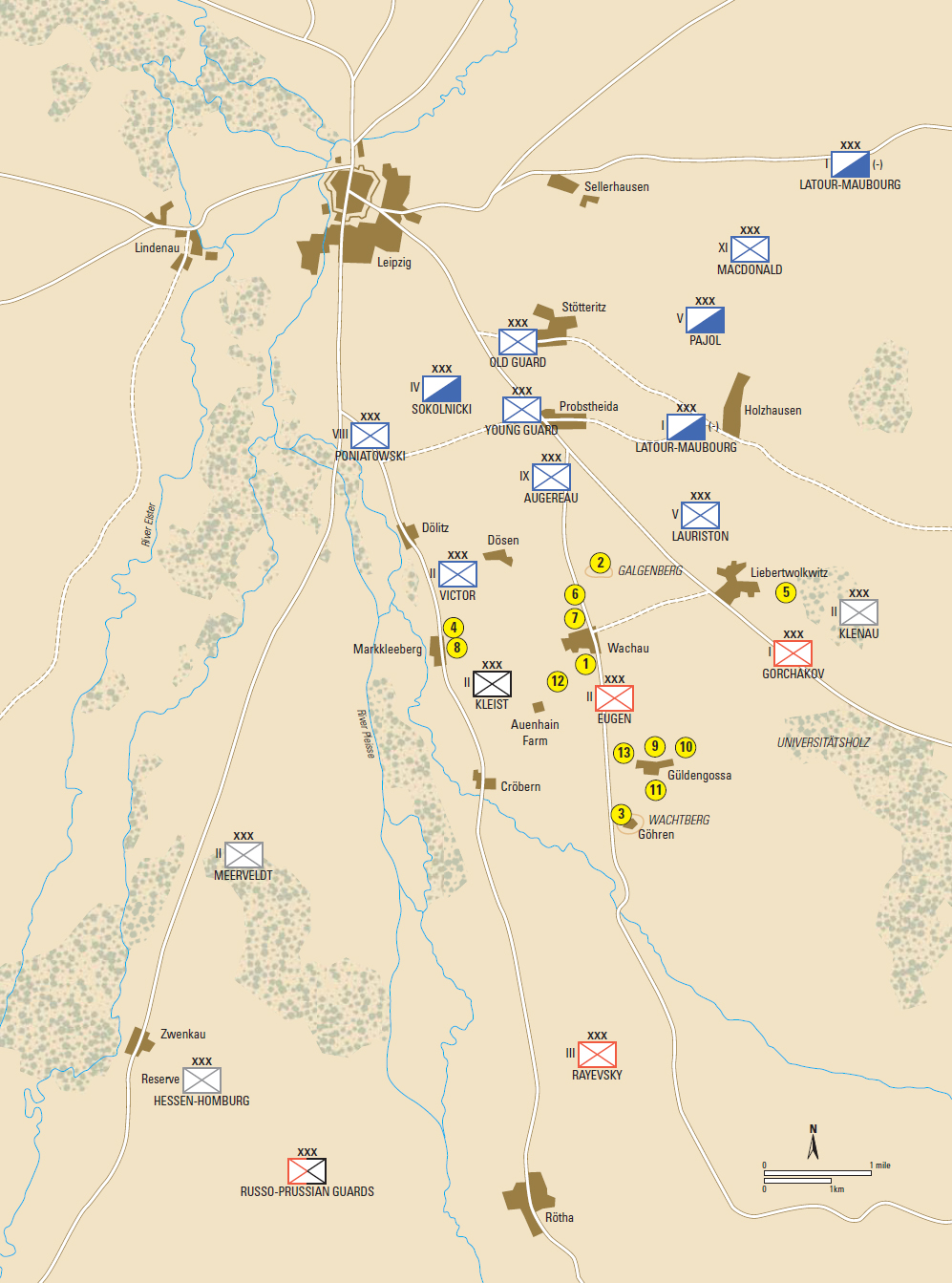

At dawn on 16 October, the Russian Lifeguard and Prussian Royal Guard, about 14,000 strong, were in reserve at Rötha, about 10km (two or three hours’ march) to the south of the Allied left wing. All four Young Guard infantry Divisions, grouped into two corps under Maréchaux Oudinot and Mortier, were located behind and to the north of Lauriston’s V Corps, which was deployed between Wachau and Liebertwolkwitz (Smith 2001: 69). Both the Young Guard and the Russian Lifeguard would be held in reserve for much of the day.

As the Allied armies were pushed back, Oudinot’s corps with other elements of the Imperial Guard and a large formation of cavalry were ordered to take up a position near Meusdorf Farm. Napoleon ordered Oudinot to capture Auenheim Farm, while Mortier’s II Young Guard Corps and Lauriston’s V Corps were to capture the Universitätsholz. Once these positions had been seized, Murat with his cavalry was to move forward and roll up the lines of the Army of Bohemia. Therefore these positions had to be held by the Allies at all costs.

The French pounded the Allied positions with their massed artillery. According to one Russian officer, ‘all hell was really let loose. It seemed impossible that there could be any space between the bullets and the balls which rained onto us’ (quoted in Smith 2001: 95). Shortly after 1400hrs, Général de division Bordesoulle’s 1st Heavy Cavalry Division advanced, supported by French infantry. According to the Russian officer, ‘From the direction of the front came a dull, deep rumbling noise, like the rattling of a thousand heavy chains. It was the sound of hooves and weapons’ (quoted in Smith 2001: 96). Murat’s cavalry hit Eugen von Württemberg’s II Infantry Corps to the north-west of Güldengossa, while the infantry of Lauriston’s V Corps attacked Lieutenant-General Andrey Gorchakov’s I Infantry Corps to the north-east. Général de division Maison’s 16th Infantry Division of Lauriston’s V Corps was to capture Güldengossa itself.

The three Prussian battalions garrisoning the town put up a stiff resistance, but were pushed back through the streets and houses of Güldengossa. However, the St Petersburg and Tauride Grenadier regiments of Major-General P.N. Choglokov’s 1st Grenadier Division soon arrived, and after heavy fighting forced Maison’s 16th Infantry Division to withdraw.

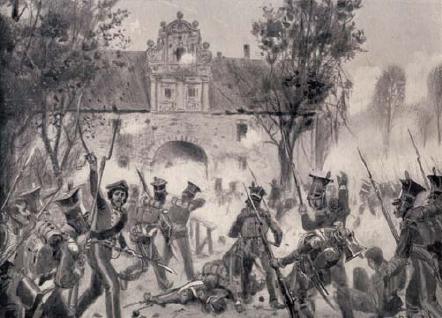

The fight for Wachau, by Richard Knötel. Here Polish troops fighting for Napoleon attempt to storm an imposing building in the village; the confusion and poor visibility prevalent in this sort of combat are well conveyed. Wachau resisted the Coalition forces’ assaults on 16 October, but was later abandoned by Napoleon’s men. (RC)

The 2nd Voltigeurs and the Finland Guards Regiment at Leipzig, 16 October 1813

0800hrs: Eugen von Württemberg, having deployed his forces north of Güldengossa in the dark, advances on Wachau, which is evacuated by the French; Napoleon’s men contain the Allies’ advance out of the village with artillery fire, and Victor counter-attacks Wachau and regains it by 0930hrs.

0800hrs: Eugen von Württemberg, having deployed his forces north of Güldengossa in the dark, advances on Wachau, which is evacuated by the French; Napoleon’s men contain the Allies’ advance out of the village with artillery fire, and Victor counter-attacks Wachau and regains it by 0930hrs.

0900hrs: Napoleon visits Murat’s HQ at the Galgenberg and is briefed on the situation; he decides to send elements of the Young Guard under Mortier and Curial’s 2nd Old Guard Infantry Division to support Liebertwolkwitz, and two Divisions of the Young Guard under Oudinot, along with a large cavalry force, move up behind Wachau in support. French artillery numbering 100 pieces and deployed on the high ground between Wachau and Liebertwolkwitz commences fire, which continues for roughly five hours.

0900hrs: Napoleon visits Murat’s HQ at the Galgenberg and is briefed on the situation; he decides to send elements of the Young Guard under Mortier and Curial’s 2nd Old Guard Infantry Division to support Liebertwolkwitz, and two Divisions of the Young Guard under Oudinot, along with a large cavalry force, move up behind Wachau in support. French artillery numbering 100 pieces and deployed on the high ground between Wachau and Liebertwolkwitz commences fire, which continues for roughly five hours.

0900hrs: Tsar Alexander arrives on the battlefield and observes the battle from the Wachtberg, between Güldengossa and Göhren; he is later joined by the Prussian and Austrian monarchs. Alexander decides to commit the Russian Lifeguard and Prussian Royal Guard, plus the grenadier regiments of Rayevsky’s III Infantry Corps.

0900hrs: Tsar Alexander arrives on the battlefield and observes the battle from the Wachtberg, between Güldengossa and Göhren; he is later joined by the Prussian and Austrian monarchs. Alexander decides to commit the Russian Lifeguard and Prussian Royal Guard, plus the grenadier regiments of Rayevsky’s III Infantry Corps.

0930hrs: Kleist captures Markkleeburg from Poniatowski’s VIII Corps; the village changes hands ten times by early afternoon.

0930hrs: Kleist captures Markkleeburg from Poniatowski’s VIII Corps; the village changes hands ten times by early afternoon.

1000hrs: Klenau commences his advance, quickly taking much of Liebertwolkwitz but losing it again just as rapidly.

1000hrs: Klenau commences his advance, quickly taking much of Liebertwolkwitz but losing it again just as rapidly.

1000hrs (approx.): Following an hour-long artillery and musketry duel, Allied forces storm Wachau but are unable to hold it in the face of a French counter-attack, which retakes the village by 1100hrs. The soldiers of Eugen’s von Württemberg’s 3rd and 4th Infantry Divisions suffer appallingly from French artillery fire.

1000hrs (approx.): Following an hour-long artillery and musketry duel, Allied forces storm Wachau but are unable to hold it in the face of a French counter-attack, which retakes the village by 1100hrs. The soldiers of Eugen’s von Württemberg’s 3rd and 4th Infantry Divisions suffer appallingly from French artillery fire.

1300hrs (approx.): Victor’s II Corps attacks Wachau, supported by the 2nd Old Guard Infantry Division; the Allied defenders fall back.

1300hrs (approx.): Victor’s II Corps attacks Wachau, supported by the 2nd Old Guard Infantry Division; the Allied defenders fall back.

1400hrs (approx.): Kleist’s forces still hold much of Markkleeberg, but by this time all the other Allied forces have been driven back to their starting positions. Napoleon decides not to wait for Marmont and Ney, and has already despatched Bertrand to defend Lindenau; he launches a general advance by the Young Guard, Lauriston’s V Corps, Victor’s II Corps and the Old Guard.

1400hrs (approx.): Kleist’s forces still hold much of Markkleeberg, but by this time all the other Allied forces have been driven back to their starting positions. Napoleon decides not to wait for Marmont and Ney, and has already despatched Bertrand to defend Lindenau; he launches a general advance by the Young Guard, Lauriston’s V Corps, Victor’s II Corps and the Old Guard.

1400hrs (approx.): Napoleon orders forward Murat’s 8,000 to 10,000 cavalrymen, who penetrate the Allied lines as far as beyond Güldengossa, but as they are unsupported by infantry or artillery, they are consequently dispersed and driven back to their own lines.

1400hrs (approx.): Napoleon orders forward Murat’s 8,000 to 10,000 cavalrymen, who penetrate the Allied lines as far as beyond Güldengossa, but as they are unsupported by infantry or artillery, they are consequently dispersed and driven back to their own lines.

Mid-afternoon: Dubreton’s 4th Infantry Division leads Victor’s II Corps into Güldengossa, only to be repulsed by the Prussian defenders.

Mid-afternoon: Dubreton’s 4th Infantry Division leads Victor’s II Corps into Güldengossa, only to be repulsed by the Prussian defenders.

1600hrs (approx.): The grenadier regiments of Rayevsky’s III Infantry Corps and the Lifeguard regiments of Ermolov’s V Infantry Corps are committed against Güldengossa, while Austrian grenadiers and cuirassiers advance on Auenhain. Some 80 guns of the Russian Guards Artillery deploy on the heights south of the village. Maison’s 16th Infantry Division and Young Guard regiments counter-attack Güldengossa, running the gauntlet of Russian artillery fire, but are repulsed by elements of Udom’s 2nd Lifeguard Infantry Division.

1600hrs (approx.): The grenadier regiments of Rayevsky’s III Infantry Corps and the Lifeguard regiments of Ermolov’s V Infantry Corps are committed against Güldengossa, while Austrian grenadiers and cuirassiers advance on Auenhain. Some 80 guns of the Russian Guards Artillery deploy on the heights south of the village. Maison’s 16th Infantry Division and Young Guard regiments counter-attack Güldengossa, running the gauntlet of Russian artillery fire, but are repulsed by elements of Udom’s 2nd Lifeguard Infantry Division.

Late afternoon: Oudinot’s I Young Guard Infantry Corps passes Wachau and captures Auenhain; elements of Mortier’s II Young Guard Infantry Corps advance into the Universitätsholz, but are thrown out again by Klenau’s Austrians.

Late afternoon: Oudinot’s I Young Guard Infantry Corps passes Wachau and captures Auenhain; elements of Mortier’s II Young Guard Infantry Corps advance into the Universitätsholz, but are thrown out again by Klenau’s Austrians.

1700hrs (approx.): The French mount another infantry attack on Güldengossa but are pushed back; Maison is almost captured. Following Allied cavalry attacks all along this front, the situation has turned to the Allies’ advantage, with Napoleon’s cavalry having been thrown back, his infantry advance halted, and his reserves fully committed.

1700hrs (approx.): The French mount another infantry attack on Güldengossa but are pushed back; Maison is almost captured. Following Allied cavalry attacks all along this front, the situation has turned to the Allies’ advantage, with Napoleon’s cavalry having been thrown back, his infantry advance halted, and his reserves fully committed.

Battlefield environment

The weather in the Leipzig area was cold, wet and foggy on 16 October 1813; it had been a very windy night, damaging roofs and uprooting trees. Recent heavy rain meant that the ground was muddy, impeding movement, and the fields around the various villages around Leipzig featured several ponds, dams, ditches, fences and other obstacles to hinder the advance of a formed body of soldiers.

The flat-topped hills south of Leipzig favoured Napoleon because they provided good artillery positions and masked his troop movements from the Allies. The Allied commanders made surprisingly poor choices when deploying their troops, given that they must have known about the swampy and overgrown nature of the land between the Elster and Pleisse rivers, which would constrain their actions (Smith 2001: 72).

The villages were formidably strong defensive positions, offering excellent cover and fields of fire across the muddy stretches of land between them. Village houses were largely made of stone and surrounded by high stone walls, and the bridges over the River Pleisse south of Leipzig had been put out of action by the defenders.

At this point it is worth pausing and building a more detailed picture of the nature of the fighting in Güldengossa, by consulting first-hand accounts of similar struggles being conducted elsewhere during the battle. The village of Schönefeld, north-east of Leipzig, witnessed similarly prolonged and bloody fighting on 18 October. According to one report:

The flames which kept spreading through Schönefeld (nothing being done to halt them), combined with the tenacious defence, obliged the Russians to vacate the village a second time. Many wounded of both sides were burnt to death … Local people said that the noise and shouting of the troops, the sound of artillery and small-arms fire, the landing and explosion of shells, the howling, moaning and lowing of human beings and cattle, the whimpering and calls for help from the wounded and those who lay half-buried alive under masonry, blazing planks and beams was hideous. The smoke, dust and fumes made the day so dark that nobody could tell what time it was. (Quoted in Brett-James 1970: 178–79)

Conditions like these must have proved frightening and disorienting for both sides in the battle for Güldengossa; black-powder warfare generates substantial amounts of dirty-white smoke even in open countryside, and so visibility must have been poor, impeding command and control (Maughan 1999: 30). The very act of storming a village, whose narrow streets and passageways would play havoc with close-order formations, meant that even after a successful attack, the new occupiers risked being disordered and vulnerable if they were counter-attacked before consolidating their position. With respect to the struggle for Schönefeld, the Russian senior commander in that sector, General of Infantry Louis Langeron, later recalled:

I believed the position was assured and went forward of the village to establish a chain of outposts. At this moment [Maréchal Michel] Ney [the senior French commander in that sector], who was near a mill on a hillock about five hundred yards behind the last houses in Schönefeld, launched against me so unexpected an attack, and so impetuous and well directed, that I was unable to withstand it. Five columns, advancing at the charge and with fixed bayonets, rushed at the village and at my troops who were still scattered and whom I was trying to re-form. They were overthrown and forced to retire in a hurry …

Fortunately I still had considerable reserves, and after letting the regiments which had been expelled from Schönefeld pass through the gaps between them, I soon did to the enemy what he had done to me, because my columns were in good order and his troops were by this time scattered … (Quoted in Brett-James 1970: 178)

Erstürmung der Schäferei Auenheim bei Leipzig durch die Grenadier-Bataillone Call und Fischer am 18. Oktober 1813, by Balthasar Wigand. This image, depicting events two days later, illustrates well the cross-fire that could be offered by the defenders of built-up areas, and the way that even broad avenues like the ones shown here severely constricted the close-order formations of the attackers. Note the Austrian Sappeure (infantry pioneers), wearing brown aprons over their greatcoats, wielding their axes against the large wooden door of the left-hand building; few infantrymen in the armies that contested the field at Leipzig carried such equipment, severely limiting their options in street-fighting scenarios. (Getty Images)

The confused, piecemeal nature of street-fighting was not something that infantry were specifically trained for in the Napoleonic era, and the slow-firing, lengthy muskets that armed both sides must have been difficult to wield in the cramped confines of Güldengossa and other villages like it. Replenishing ammunition and water supplies would have proved very difficult, and like all black-powder weapons the muskets used by soldiers of both sides would have quickly fouled up with residue, making it harder to reload and increasing the risk of misfires (Maughan 1999: 27).

To return to the battle for Güldengossa: Maison counter-attacked and regained part of the town, before the Guards Jaeger Regiment was committed, and along with other regiments performed a bayonet charge to seize the town once more. This time, Napoleon ordered Oudinot’s corps to support the 16th Infantry Division. The French advanced in three columns – Pacthod’s 1st Young Guard Infantry Division probably on the right, with Decouz’s 3rd Young Guard Infantry Division in the centre and Maison’s 16th Infantry Division forming the third column, which was probably positioned to the left of the Young Guard formations – supported by artillery fire. Once more the French entered Güldengossa and again the town changed hands.

Things began to look bleak again for the Allies and some of the senior commanders began to consider ordering a retreat. Tsar Alexander had other ideas, however. After sending the Cossacks of the Lifeguard to help intercept the French cavalry, he rode up to the Finland Guards Regiment which, according to Lieutenant-Colonel Apollon Nikifoeovich Marin, was ‘impatient, anticipating the minute of joining the battle’ and shouted, ‘Lads! To the fight! God be with you!’ (quoted in Marin 1846 39). According to Pamfil Nazarov of the Finland Guards Regiment, the Tsar ordered the regiment ‘to load our muskets and join the battle’ (Nazarov 1874: 536). Now it was their turn, along with the Guards Life Grenadier Regiment, which had been incorporated into the Lifeguard in April 1813.

Tsar Alexander watches the Finland Guards Regiment advancing towards Güldengossa, 16 October 1813. A wounded officer (right), probably Major-General Kryzhanovsky, is being stretchered off the battlefield, while his regiment continues its advance. (From S. Gulevich’s Istoria Leib Gvardii Finlandskago Polka)

Major-General Karl Ivanovich Bistrom, now a brigade commander in the 2nd Lifeguard Infantry Division, commanded the Russian regiments that were to retake the town – a mixture of units from Choglokov’s 1st Grenadier Division and the two Lifeguard Infantry Divisions. The plan was to launch a three-pronged attack. The Finland Guards Regiment was to attack the left side of the town, while the St Petersburg Grenadier Regiment closed in from the right. The Guards Life Grenadier Regiment and Guards Jaeger Regiment, plus the Tauride Grenadier Regiment, were to attack the centre.

The 1st and 2nd Battalions of the Finland Guards Regiment would advance towards the left edge of the town, while the 3rd Battalion, under the command of Colonel Alexander Karlovich Zherve, would make a circling movement and attack the sector closer to the middle of the town. The 1st and 3rd Battalions would simultaneously attack, while the 2nd Battalion, under Colonel Peter Sergeevich Ushakov, would remain in reserve. The battalions’ advance would be preceded by skirmish chains, which would clear the way of any enemy skirmishers. Marin’s history also mentions a Prussian volunteer battalion that accompanied the Finland Guards Regiment in the assault.

When the Finland Guards Regiment was ordered to advance, the soldiers gave a loud ‘Ura!’ and began moving forward in three battalion columns towards Güldengossa at a steady pace in order to maintain formation. They had not gone far when they were met by a hail of musket shot and cannonballs, succeeded by caseshot as the Russians drew nearer to the town. Pamfil Nazarov was one of those to be hit:

I was wounded by a bullet in the right leg above the knee which injured the nerve and several shots passed through my greatcoat and my wound started to bleed, so warm, like warm water. And immediately I began to retreat, but a little way feeling the pain I fell face down on the ground and lay I do not remember how long. A wounded sergeant of our company approached me and recognising me began to lift me up. (Nazarov 1874: 536)

However, with musket balls flying past them, the sergeant left Nazarov to find his own way to safety. Meanwhile the Finland Guards Regiment continued their advance upon Güldengossa, without firing a shot, but taking casualties all the way. Entire ranks fell ‘but nothing was able to hold their steadfastness’ (Gulevich 1906: 307). The 2nd Battalion stopped close to the town as planned while the 1st Battalion, under the command of Colonel Alexander Krestyanovich Shteven, continued its march on Güldengossa.

Soldiers of the Finland Guards Regiment climbing over the walls of Güldengossa. Note how the buildings are gutted and roofless; fire spread quickly in black-powder battle, even in sturdy stone-built villages such as those surrounding Leipzig. (From S. Gulevich’s Istoria Leib Gvardii Finlandskago Polka)

It is striking that the Finland Guards Regiment did not fire during the assault, but it should be borne in mind that it was well recognized at the time that once infantry began to fire, it was extremely difficult for the regimental officers to compel them to cease fire and resume the advance (Muir 2000: 79). The first volley was carefully husbanded until the optimal moment, as it was likely to be much more effective than subsequent volleys. This was for a number of reasons – not least the progressive wear and tear on the muskets themselves, and the distracting influence of the noise and confusion of battle on the soldiers as they tried to reload (Muir 2000: 78). In fact, the decision to have the regiment load its muskets before setting off would have maximized the impact of that first precious volley, as the lengthy and complicated loading drill would have been much more successful in relatively calm conditions before the advance began.

Korennoi’s exploits at Güldengossa, depicted in this 1846 painting by P.I. Babayev. According to tradition Napoleon is said to have ordered that word of Korennoi’s feats should be published throughout the Grande Armée as an example of Russian bravery. This seems unlikely and no such proclamation has been found. Note the bare-footed prone figure in the foreground; even in the heat of battle, survivors appropriated the shoes and clothing of the dead or wounded to replace their own, meaning the fallen were quickly stripped of their possessions. (AM)

When the 3rd Battalion reached the outskirts of the town, Zherve and several of his officers climbed over a stone wall first, followed by some of their men. However, they were immediately surrounded by the enemy – likely to have been soldiers of Pacthod’s 1st Young Guard Infantry Division – who began a fierce fire-fight and then as the French closed in on this band of Russians, hand-to-hand fighting broke out. A small group of soldiers of the Finland Guards Regiment, including Grenadier Leontii Korennoi of the 3rd Grenadier Company, helped Zherve and other officers get back over the wall, while another group held off the French. Slowly this small band of Russians were cut down one by one; Korennoi shouted, ‘Do not give up lads!’ Finally he was the last survivor and with a broken musket he continued to fight off the French as long as he could. With heaps of dead and wounded Frenchmen at his feet he, too, was overpowered.

By now the other battalions had arrived and engaged the other regiments of Pacthod’s Division. Climbing over the dead and wounded from the previous attacks, the Finland Guards Regiment burst through the streets of Güldengossa and fought ‘with incredible bravery’. The French were firing from every house, stone wall or other obstacle, and so had to be driven from these defences one by one. However, the Finland Guards Regiment was suffering heavy losses in the street fighting. Twice they had to fall back due to weight of French numbers, but on the third assault the Russians managed to seize their allotted sector of the town.

The other Russian regiments were also making good progress despite the fierce resistance they were encountering; finally the French were driven from the town and it was their turn to counter-attack. Again, the Young Guard managed to gain a foothold in the town, only to lose it once more. It was probably this attack that Major Charles Pierre Lubin, Baron Griois of the Guard Foot Artillery, recalls:

Towards evening, we took up a position more in the rear several hundred fathoms from where we continued our fire, principally directed on a town a little forward from our left, Gossa, I believe the enemy occupied. Several infantry attacks were made to seize [this town] but in vain. When night had almost fallen a final assault was vigorously executed and to the repeated shouts of ‘Vive le Emperor!’ against this town by two divisions of the Young Guard under the orders of General Curial [sic]. But he had no more success than the previous attacks. (Griois 1909: I.246)

Mêlée in Güldengossa

Here we see the soldiers of Korennoi’s 3rd Grenadier Company – distinguished by their moustaches, long shako-plumes and red-over-light-blue pompons – striving to protect their commander, Colonel Zherve (right), as he hurriedly withdraws. We have chosen to depict the Finland Guards Regiment in greatcoats and winter legwear; it is not clear when in the 1813 campaign the summer garb gave way to the winter equivalent.

The French attackers, voltigeurs of Pacthod’s Division, also wear greatcoats; only the NCO at left retains the sabre.

The smoky, noisy battlefield must have proved a bewildering setting for the soldiers of both sides as they contested the stone buildings of Güldengossa and the other settlements to the south of Leipzig.

The Young Guard were driven out of the town again with heavy losses. In his report Bistrom stated: ‘Major-General Kryzhanovski, as is well known a brave general with his detachment, that is the Finlandski and St Petersburg Regiments, utterly drove the enemy out from the left side of the town’ (Gulevich 1906: 308). The Tsar had witnessed the regiment’s action and sent his brother the Grand Duke Constantine, always a stickler for military discipline, to congratulate the regiment in person, saying ‘Thank you, Finlandski, the sovereign saw you and orders me to give his thanks’. To which the regiment shouted, ‘Ura! Very good, sir!’ All this time the sound of musket shots could still be heard (Marin 1846: 40).

Pamfil Nazarov, Finland Guards Regiment

In the ranks of the 6th Jaeger Company of the Finland Guards Regiment was a young recruit called Pamfil Nazarov. He had been among the reinforcements who joined the regiment in July 1813 in time to take part in the siege of Danzig. He watched as the elements of Schwarzenberg’s army advanced, only to be pushed back towards Güldengossa.

Nazarov, who was wounded at the beginning of his regiment’s assault on the town, would wander the lanes of Saxony for the next 13 days with other wounded comrades looking for treatment. It would not be until he reached Pleven that he finally found help. By then his leg had become badly infected. He records that the town was full of wounded and he was sent to a church that had been converted into a makeshift hospital housing 400 patients. For more than six weeks he remained there, while his leg slowly healed. When he finally recovered he found that his right leg was now 2cm shorter than the left one. Upon his discharge from hospital he had a relapse after only marching 6.5km, so that he had to be hospitalized again. He recovered, however, and witnessed the surrender of Paris in 1814.

Nicolas Marchal, 2nd Voltigeurs

In striking contrast to the young and inexperienced Nazarov, who was experiencing his first battle, the 2nd Voltigeurs’ regimental commander, Nicolas Marchal, was a 43-year-old veteran who had been wounded as long ago as 1793 and had survived the rigours of the Russian campaign, despite being wounded at Borodino.

Like all regimental commanders, Marchal would probably have been mounted during the battle of Leipzig; this would have improved his view of events, but made him a more prominent target. Orders would have reached him via messenger, and he would have issued his own instructions verbally, employing his regimental staff officers to convey his orders.

Major Marchal had led the 2nd Voltigeurs for only a short time in mid-October 1813, having been transferred from the 93rd Regiment of the Line to replace Jean-Paul-Adam Schramm, the 2nd Voltigeurs’ young commander in the earlier battles of the 1813 campaign, following the latter’s promotion to Général de brigade. Marchal would survive the battle of Leipzig and take command of the reconstituted 7th Voltigeurs in the fateful ‘Hundred Days’ campaign of 1815.

By now it was night and the darkness put an end to the fighting. At the beginning of the battle the Finland Guards Regiment had mustered 48 officers, 140 NCOs, 43 musicians, 1,195 men and 83 non-combatants. However, despite attacking towards the end of the day it suffered four officers killed, four officers mortally wounded, 15 officers badly wounded, eight NCOs killed and 32 wounded, and 90 men killed, 292 wounded and 42 missing – a casualty rate of 52.1 per cent for the officers and 33.6 per cent for the other ranks. In all it had fired 60,200 cartridges, an average of about 50 shots per man (Rostkovski 1881: 197).

The commander of the Finland Guards Regiment, Major-General Kryzhanovsky, received four wounds while leading the regiment towards Güldengossa. Despite having been hit by three bullets in the legs, he did not abandon his post until he was struck in the chest, which caused a severe contusion. With his chest swelling, making it difficult to breathe, and blood flowing from his leg wounds he was finally forced to abandon the field. All three of the battalion commanders – Shteven, Zherve and Ushakov – were also wounded. Each would receive the Order of St George, the highest military award. Their citation read, ‘being despatched to capture by assault the left flank of the town, with excellent courage and fearlessness attacked at the bayonet point and putting to flight superior forces of the enemy, [and] stubbornly defending the town’ (Gulevich 1906: 311). Other officers gained lesser awards and some also received financial rewards, Kryzhanovsky being awarded 500 gold roubles and Shteven 300 gold roubles, while others received either 100, 60 or 50 gold roubles.

The lower ranks also benefited, receiving the Leipzig medal; the Emperor of Austria gave one gold and two silver medals with scarlet ribbons for the commander of the regiment to award to the three most deserving soldiers. Likewise the King of Prussia gave 12 silver medals. As a battle honour the regiment received two silver trumpets with the inscription, ‘To the Finlandski Regiment of the Imperial Guard in reward of the distinguished valour, bravery and fearlessness shown in the battle of Leipzig, October 4, 1813’, the Julian calendar observed by the Russians being 12 days behind the Gregorian calendar employed by the rest of Europe.

Among the regiment’s wounded was Grenadier Leontii Korennoi, who had been in the regiment since its formation and had distinguished himself at Borodino, for which he received the St George’s Cross. During the hand-to-hand fighting it is said that he received 18 bayonet wounds before being taken prisoner. However, according to Lieutenant Marin he ‘was covered in wounds, but luckily all the wounds were not serious’. According to tradition Napoleon visited a makeshift hospital and hearing of his bravery he had Korennoi brought to him. ‘For what battle did you get this cross?’ Napoleon is alleged to have said, pointing towards his St George’s Medal. ‘For Borodino,’ Korennoi replied. Napoleon patted him on the shoulder and ordered that he be released after the battle. A few days later Korennoi rejoined the men of his regiment, who were overjoyed to see ‘Uncle Korennoi’ again.

Owing to its losses, the Finland Guards Regiment would take no further part in the battle. Out of necessity the 2nd Voltigeurs, along with the other regiments of the Young Guard, would go on to fight and sustain heavy casualties on the 18th and 19th. Unfortunately, no such detailed data exists for the Young Guard at Leipzig, but the officer-casualty figures are known: the 2nd Voltigeurs had no officers killed, but one officer, a Capitaine Daviel, was wounded on the 16th; a further seven officers of the regiment would be wounded in the coming three days. On 1 August 1813, the two battalions of the 2nd Voltigeurs mustered 33 officers and 902 other ranks (Oliver & Partridge 2002: 17); by 1 November 1813, the regiment totalled just 25 officers and 281 other ranks.

As for the battle, for the Allies in the southern sector the Tsar had thrown in the reserves just at the right moment. The French cavalry had been forced to retreat, and with the Allied recapture of towns like Güldengossa Napoleon had failed in his aim of defeating Schwarzenberg’s Army of Bohemia. Napoleon had also come very close to besting Blücher’s Army of Silesia to the north of Leipzig, but he had to commit his reserves early in the battle so when the crisis came, he lacked the troops to inflict a decisive reverse on the Allies on 16 October. The Allies had lost about 38,000 men killed and wounded and 2,000 taken prisoner, whereas Napoleon’s losses have been estimated at 23,000, with 2,500 captured. It had been the bloodiest day since Borodino, a record that would not be broken until World War I.

Even while the fighting had been raging, Allied units were force-marching towards the battlefield. The Crown Prince of Sweden, the former Maréchal Bernadotte, arrived the following day. Napoleon knew of these reinforcements; he also knew that to withdraw now might lead to the disintegration of his army. Therefore he decided to stand and fight on the 18th. In the mean time both sides licked their wounds on 17 October. Napoleon drew his battle line closer to Leipzig, so shortening the line of his weakened army. The clashes on 18 and 19 October were disastrous reverses for Napoleon, with the Saxons and Württembergers deserting to the Allies, and his decisive defeat at Leipzig all but put an end to Napoleon’s domination of Germany.