11

And naught was left King Alfred

But shameful tears of rage,

In the island in the river

In the end of all his age.

In the island in the river

He was broken to his knee:

And he read, writ with an iron pen,

That God had wearied of Wessex men

And given their country, field and fen,

To the devils of the sea.

G. K. CHESTERTON, The Ballad of the White Horse (1911)1

In March 878, seeking refuge, King Alfred came to Athelney, a hidden spit of land, rising gently from the bleak expanse of the Somerset Levels.

He had led his battered court to this remote place in the short dark days of January and February, ‘leading a restless life in great distress amid the woody and marshy places of Somerset’.2 The language of the Anglo-Saxon Chronicle, with its woods (wuda) and moor-fastnesses (mór-fæstenas), recalls the monster-haunted wildernesses of Beowulf and St Guthlac, drawing, with allusive economy, a world at the margins of human life – a place of estrangement and shadow-life. Asser tells us that the king ‘had nothing to live on except what he could forage by frequent raids, either secretly or even openly, from the Vikings as well as from the Christians who had submitted to the Vikings’ authority’. Alfred was a king turned wulvesheofod (‘wolf’s head’), his tenure in the wilderness an inversion of the order of Anglo-Saxon life. Alfred, like Grendel, had become the sceadugenga – the ‘shadow-walker’ – the wolf beyond the border ‘who held the moors, the fen and fastness …’3

These days, Athelney is a nondescript lump of ground, surrounded by the flat fields of the Somerset countryside. But when the flood tides come – as they did in with devastating effect in 2012 and 2014 – we can see it again as Alfred saw it: white sky and white water, the sheet of pale gauze split by the black fingers of the trees, torn by sprays of rushes, limbs of willow lightly touched with sickly green, catkins swinging like a thousand tiny sacrifices. Off in the distance a heron hauls itself skyward, spreading wide black pinions, beating a lazy saurian path across the Levels. The other birds carry on their business, snipe and curlew boring surgical holes into the shallows. The plop of a diving frog adds percussion to the throaty chorus of his fellows, lusty young bulls emerging bleary-eyed from their winter beds, seeking out mates to tangle with in the mud.

Later in his life, Alfred would invest in Athelney by founding a monastery there, perhaps in gratitude and recognition for the role it had played in his career, or perhaps as part of his campaign of self-mythologization. ‘Æthelingaeg’ is how Asser spells it, though the manuscripts of the Anglo-Saxon Chronicle present various different iterations. It means ‘isle of princes’ (Æðeling ‘prince’ + eíg ‘island’), an auspicious name for a royal refuge and one which we might suspect was bestowed only after it had played its part in Alfred’s story. He would also establish a stronghold there, a ‘formidable fortress of elegant workmanship’ connected to the island by a causeway, the genesis of the modern village of East Lyng.4 But at the time he came there in 878 it was an isolated place – cut off amid the swollen waters of the Levels, an island, ‘surrounded’ as Asser explained ‘by swampy, impassable and extensive marshland and groundwater on every side’.5

In 878, Athelney was a place where Alfred could hide from his Viking enemies and plan his attacks against them – attacking them ‘relentlessly and tirelessly’.6 It would briefly become for him the seat of a guerrilla government in exile, of a king without a kingdom, an Avalon unto which the king would pass and where he would be reborn.

It had taken several years for the situation in Wessex to reach this sorry pass. By 875, Northumbria and East Anglia had fallen to Viking armies, and Mercia was riven by faction and war, its ancestral tombs ransacked and defiled. Only Wessex had weathered the Viking storm and remained intact: the military resolve of Alfred and his people had delivered four years of peace. That peace, however, was now over and in 875 the king’s warriors fought (and won) a maritime skirmish with a raiding fleet. One Viking ship was captured and six (Asser says five) were driven off. This, however, was only the opening move in a new war for the West Saxon kingdom.7

In 876, the army that had been led to Cambridge from Repton by Guthrum, Oscetel and Anwend moved suddenly into Wessex and occupied Wareham, a fortified convent in Dorset. Crisis seemed initially to have been averted through negotiation – hostages were exchanged and the Viking army swore holy and binding oaths – but it transpired that this Viking force had no particular intention of leaving Wessex. The army slipped away from Wareham by night, executing the hostages granted by Alfred (we can imagine that the Vikings held by the West Saxon army suffered a similar fate in return) and moved on to occupy Exeter in Devon. Alfred gave them good chase, but once again the limitations of early medieval siegecraft sucked all the momentum from the campaign: the king ‘could not overtake them before they were in the fortress where they could not be overpowered’.8 Had it not been for the weather, things might have looked bleak for Wessex – 120 Viking ships were lost in a storm near Swanage, preventing them from linking up with their comrades at Exeter.9 The result, yet again, was a stalemate, and once more hostages were exchanged (none of whom can have felt very optimistic about his future) and oaths sworn; this time, perhaps sapped of confidence as a result of the failure of their planned pincer-movement, the Viking army did indeed withdraw. They went, in fact, to Mercia, where they formally carved up Ceolwulf’s kingdom, leaving the latter a rump part, and saw out the winter in Gloucester.10

This occurred in 877, and we know nothing of what befell Ceolwulf and his subjects in that, presumably depressing, period. It is likely, however, that the time spent in Mercia was used by the Viking army to consolidate their land-taking and to gather reinforcements. Soon after Twelfth Night (7 January) in the deep winter of early 878, the Viking army rode south into Wessex, to the royal estate at Chippenham in Wiltshire. They probably came via Cirencester, joining the Fosse Way and cutting through southern Gloucestershire like a dagger, before turning to the south-east. No early sources record whether Alfred was himself present at Chippenham, or whether he fought the Vikings there. All we are told (to give Asser’s version) is that ‘By strength of arms they forced many men of that race [West Saxons] to sail overseas, through both poverty and fear, and very nearly all the inhabitants of that region submitted to their authority.’11

Chippenham was occupied by Guthrum’s army and Alfred began his period of exile in the wilderness. It was approximately ninety years since the first recorded Viking raids on England had taken place; in that short time, every one of the Anglo-Saxon kingdoms had been broken.

In later days in was said that St Cuthbert appeared in a vision to Alfred on Athelney. The speech that the king received was the stuff to put fire in the belly of any dynastic ruler: ‘God will have delivered to you your enemies and all their land, and hereditary rule to you and to your sons and to your sons’ sons. Be faithful to me and my people because to you and your sons was given all of Albion. Be just, because you have been chosen as king of all Britain.’12 The story was added to the Alfred myth after the king’s death, in either the mid-tenth or mid-eleventh century,13 and Asser makes no mention of it. It seems likely to have been a tale spun during the reign of Alfred’s grandson to prop up his political ambitions and solidify the standing of the cult of St Cuthbert. Nevertheless, had Cuthbert been looking down from his cloud in the 870s, he would have seen plenty of things which might have given him cause to visit destruction on the Vikings – not least the disturbance of his incorruptible slumber. The sack of his former monastery at Lindisfarne in 793 was, by then, a story from another age, but the arrival of the micel here in Northumbria was another matter. Heathen warlords were now in positions of power across the north, their people settling and dividing up the land. The reappearance of Halfdan on the Tyne in 875, ‘devastating everything and sinning cruelly against St Cuthbert’,14 seems to have been what galvanized the monks to remove Cuthbert’s precious bones from their resting place on Lindisfarne. According to the Historia de Sancto Cuthberto, so began seven years of wandering for Cuthbert’s corporeal remnants, a terrestrial Odyssey of northern Britain designed, perhaps, to spare these relics the indignities that had befallen the dead of Repton. They finally came to rest at Chester-le-Street where they remained until 995, when they were disturbed once more.

If it was not Cuthbert’s discorporate exhortations, it may be that something else galvanized Alfred to action. Perhaps it was the news that Odda, ealdorman of Somerset, had destroyed a Viking army that had arrived with twenty-three ships in Devon. His victory came at an unidentified hill-fort called ‘Cynwit’.15 In the fighting, the Viking leader Ubbe, slayer of King Edmund, son of Ragnar Loðbrók and brother to Halfdan and Ivar the Boneless, was killed.16 Moreover, the Anglo-Saxon Chronicle notes, ‘ðær wæs se guðfana genumen þe hie hræfn heton’ (‘there was taken the banner that they called Raven’).17 A later gloss on this passage adds that the banner had been woven by three sisters, the daughters of Ragnar Loðbrók, in a single day: when the banner caught the breeze and the raven’s wings flapped, then victory in battle was assured; if it hung lifeless, defeat was in the offing.18 There is a great deal that might be said about ravens and banners, weird sisters and weaving, and their place on the Viking Age battlefield. For now, however, it is sufficient to note that the seizure of such a banner would have been a considerable morale boost to the West Saxons. Although the defeat of Ubbe at Cynwit may have left Guthrum’s army in a more vulnerable position than either he or his enemies had expected, its most important consequence may have been to demonstrate to the West Saxons and to Alfred that the Vikings could be beaten, that God was on the side of the English, and that his assistance – whether mediated through St Cuthbert or not – was more than a match for any heathen battle magic.

Whatever the catalyst, Alfred began to prepare. Messengers must have gone from Athelney to the ealdormen and thegns that remained loyal to him, into the shires to spread the word that the king was preparing to fight. We know that the shires had a well-developed system of hundred and shire assembly places, many of which would have been in use in Alfred’s day and probably for long ages before. It is likely that these formed the hubs for military assembly, and that to them, all over Wessex, armed men would have made their way when they received the call of their reeve, ealdorman or king. So little is known, however, of the precise mechanisms by which a West Saxon army assembled – let alone in strange circumstances like those of 878 – that any attempt to reconstruct the movements or constituents of Alfred’s army, beyond what Asser and the Anglo-Saxon Chronicle reveal, can only ever be informed speculation; indeed, the subject of how armies were raised in Anglo-Saxon England has long been a subject of intense academic scrutiny and debate.19

But we can imagine the little beginnings, the woman watching anxiously as the reeve’s messenger rides hard away, mud splattering up from the puddles of spring rain; the grave expression on her husband’s face as he walks back towards the house; the old sword he gives to his eldest son, still just a boy, to defend the farm when he is gone. We can imagine the tears and the parting, the lonely trudge past familiar fields, a spear over one shoulder, a sack over the other. On towards the hall of the thegn, to meet with other freemen of the hundred; he knows these men, has drunk with them, played games with them as a boy, one is his brother-in-law. They embrace each other and renew their friendships, ask after children and lands and livestock, tell bawdy jokes, ask dirty riddles;20 but they don’t stay long. They are nervous, though companionship helps them hide it. They need to keep moving, a small band now, singing the old songs as they go, songs of Wayland, Finn and Hengest.21

There are others on the road, little knots of armed men, some on horseback, others on foot, some in fine armour handed down from their grandfathers, garnets glittering on sword belts, gold on their horse bridles, others with little more than a padded jacket and a rusty spear. They make their way over hills and by herepath, through forests and over moors, by swift-running brooks and stagnant meres, coming together at the barrows and trees, the old stones and muddy fords – the ancient meeting places of Wessex. First the hundred, where local men were met and accounted for and news distributed, the king’s summons made plain. Then they are back on the road, a war-band now, heading for the shire-moot, to join the reeve or ealdorman – to form the fyrd (‘levied army’). As they go, further now from home, they begin to see tongues of flame shooting up from the hillsides, like the breath of dragons in the dusk: at first they think of burning villages, the harrying of Danes, before they recognize the signal fires, beacons calling the men to battle.22

When morning comes they see the camp spread out before them, the ealdorman’s war banner fluttering, gold thread glittering in the sun. But there is no time to rest and swap stories, to renew old acquaintances. News has reached them that the king is on the move.

Presently, in the seventh week after Easter he [Alfred] rode to Egbert’s Stone, which is in the eastern part of Selwood Forest (sylva magna [‘great wood’] in Latin, and Coit Maur in Welsh); and there all the inhabitants of Somerset and Wiltshire and all the inhabitants of Hampshire – those who had not sailed overseas for fear of the Vikings – joined up with him. When they saw the king, receiving him (not surprisingly) as if one restored to life after suffering such great tribulations, they were filled with immense joy. They made camp there for one night. At the break of the following dawn the king struck camp and came to a place called Iley [ASC: Iglea, ‘island wood’], and made camp there for one night.

When the next morning dawned he moved his forces and came to a place called Edington, and fighting fiercely with a compact shield-wall against the entire Viking army, he persevered resolutely for a long time; at length he gained the victory through God’s will.23

Walking on the northern rim of Salisbury Plain feels like clinging to the edge of the world – the land drops away 300 feet below the earthen banks of the fortress that crown the hillside like a circlet of turf-grown soil. The ramparts belong to Bratton Camp, a massive Iron Age hill-fort that encloses the long, mutilated hogback of a Neolithic long-barrow at its centre. Walking the perimeter, the wind rips across man-made canyons, forcing the breath back down my throat. I find that I am leaning at almost 45 degrees into the gale, and am suddenly, uncomfortably, aware of the fathoms of empty space to my right, a vast ocean of air; the plain sweeps to the north, a swathe of open country laid bare for leagues. I briefly see myself tossed like a leaf, spinning into oblivion – just another piece of organic matter on the breeze. My gut flips at the sudden feeling of vulnerability, and I begin to tack back towards the long-barrow; the sharp smell of sheep shit hits me in the nose. As I get closer to the mound an old ram with a sad face stares at me reproachfully. I ignore him, and some of his ewes go bouncing off from their grazing patch on top of the barrow, scattering in dim-witted panic.

From up here the strategic significance of the place is obvious, and it is likely that Bratton Camp was once a look-out post. The name of the ground that slopes off to the south of the hill-fort is ‘Warden Hill’, a swell of upland that runs hard up against the bedyked confines of the hill-fort. The name ‘Warden’ may very well be a development from the Old English weard (‘watch’) and dun (‘hill’). From here one can look across to the east, around 2½ miles along the line of the chalk ridge, to Tottenham Wood, the site of another Neolithic long-barrow. There are lots of English place-names with elements like ‘tut’, ‘toot’ or ‘totten’ forming part of them; though often difficult to interpret, many may originate in Old English constructions like tote-hām or tōten-hām meaning ‘house near the look-out station’ or ‘house of the watchman’.24 Both Bratton Camp and Tottenham Wood boast commanding views over the low countryside to the north, casting a watchful gaze from the rim of the plateau; down below, 2 to 3 miles from both putative look-out sites, is the meeting place of Whorwellsdown Hundred at Crosswelldown Farm.25

Looking south from the farm, Salisbury Plain rises up like a great green cliff edge, the low sun casting its man-made terraces and earthen banks into horizontal bands of undulate chromatism, like a great green tsunami surging northwards to consume the plain. Riding on that crest, both Bratton Camp and Tottenham Wood are clearly visible from the old hundred meeting place – three landmarks, each one visible to and from the others, enclosing the landscape in a triangle of watchfulness. Between them, hugging the base of the escarpment are the villages of Bratton and Edington, the latter a place that takes its name from the bleak hillside that looms over it: Eþandun – ‘the barren hill’.

Centuries before Alfred led his armies here, before the West Saxons had become Christians, they had brought their dead to Bratton Camp, to cut their graves into the ancient barrows, to lay them down among the more ancient spirits of the land. Three early Anglo-Saxon burials, revealed by nineteenth-century excavators, were dug into the long-barrow, and even earlier excavations uncovered the remains of a warrior buried with axe and sword, interred in the top of a Bronze Age round barrow that stood at the southern entrance to the camp.26 Most thought provoking of all, perhaps, was the evidence of a cremation platform discovered at the long-barrow – the remains of a pyre where the pagan West Saxons had once burned their dead.27 Up here, up on the heights, the smoke and the flames would have been seen for miles.

The theatre of such events would have impressed themselves on the imagination in ways that would not have been easy to forget, passing into folklore. Beowulf, as so often, evokes the majesty and spectacle of the ritual in ways which charcoal and fragments of burnt iron cannot:

The Geat people built a pyre for Beowulf,

stacked and decked it until it stood foursquare,

hung with helmets, heavy war-shields

and shining armour, just as he had ordered.

Then his warriors laid him in the middle of it,

mourning a lord far-famed and beloved.

On a height they kindled the hugest of all

funeral fires; fumes of woodsmoke

billowed darkly up, the blaze roared

and drowned out their weeping, wind died down

and flames wrought havoc in the hot bone-house,

burning it to the core. They were disconsolate

and wailed aloud for their lord’s decease.28

One can only speculate how long the memory of the ancestors burned and buried here would have lingered in the collective memory, what associations this landscape may have held for Alfred and his contemporaries; but it is hard to believe, even if the ancient funerals were forgotten, that the monumental remains of Bratton Camp and the numerous barrows of the chalk ridge did not exert a pull on the West Saxon imagination. The names of the long-barrows at Bratton Camp and Tottenham Wood – if they ever boasted them – are lost. But, given the evidence of Anglo-Saxon boundary clauses elsewhere, it is highly probable that names or legendary material of some type had accumulated at these monuments by the late ninth century. Places like these were deliberately sought out as venues for battle or military assembly – it was surely deliberate, for example, that Alfred should have chosen to muster his army at Egbert’s Stone before moving on to Iley Oak and Edington; it was Ecgberht (Egbert), Alfred’s grandfather, who had returned Wessex to pre-eminence among the Anglo-Saxon realms – a military hero whose memory was an appropriate one to invoke ahead of a battle that would determine the fate of his own dynasty and the future course of British history.29

There are other reasons why Edington might have been important to Alfred and why he led his army here. His father, Æthelwulf, had come here in the 850s, the place-name Edington appearing as the place of ratification for a charter granting land in Devon to a deacon called Eadberht.30 Alfred himself later bequeathed the estate at Edington to his wife, Ealhswith, along with estates at Wantage and Lambourn. (It is tempting to see in this bequest an acknowledgement of the importance of Edington to Alfred’s sense of himself – Wantage was the place of his birth, Edington of his greatest victory.) The place remained in royal hands until long afterwards. In the tenth century, royal grants of land at Edington were made to Romsey Abbey.31 It seems certain, therefore, that Edington was a royal estate centre before and after the battle that was fought there. Although nothing confirming a royal residence has yet been discovered, an early medieval spindle whorl has been found in the environs of the village,32 perhaps implying a settlement of some sort, and the remains of a royal hall may yet lie beneath the modern settlement. This in itself would be enough to explain why this place was chosen as the theatre of battle; a powerful symbol of royal authority, its occupation by either side sent a clear message to the rest of Wessex. However, when taken in combination with the evidence of a resonance both deeper and wider – ancient graves and even older monuments, military assemblies and strategic oversight, and the great geological rift in the land – it seems clear that Edington was a powerful and a fearsome place.

In Alarms and Discursions, a compendium of short works published by G. K. Chesterton in 1910, the writer and critic described his own experiences exploring this landscape.

the other day under a wild sunset and moonrise I passed the place which is best reputed as Ethandune, a high, grim upland, partly bare and partly shaggy; like that savage and sacred spot in those great imaginative lines about the demon lover and the waning moon. The darkness, the red wreck of sunset, the yellow and lurid moon, the long fantastic shadows, actually created that sense of monstrous incident which is the dramatic side of landscape. The bare grey slopes seemed to rush downhill like routed hosts; the dark clouds drove across like riven banners; and the moon was like a golden dragon, like the Golden Dragon of Wessex.

As we crossed a tilt of the torn heath I saw suddenly between myself and the moon a black shapeless pile higher than a house. The atmosphere was so intense that I really thought of a pile of dead Danes, with some phantom conqueror on the top of it […] this was a barrow older than Alfred, older than the Romans, older perhaps than the Britons; and no man knew whether it was a wall or a trophy or a tomb […] it gave me a queer emotion to think that, sword in hand, as the Danes poured with the torrents of their blood down to Chippenham, the great king may have lifted up his head and looked at that oppressive shape, suggestive of something and yet suggestive of nothing; may have looked at it as we did, and understood it as little as we.33

I don’t think that Chesterton was right about Alfred. I think the king knew full well the significance of Edington and its environs: its Bronze Age and Neolithic graves were reused by Alfred’s own Saxon ancestors as a burial ground, his royal hall was sited in their shadow. But what Chesterton clearly understood, and was able to express so powerfully, was the sheer drama, the physical presence and the intrusive – almost overpowering – impact of the environment on the imagination. His words are a reminder that landscape has the power to conjure visions and summon the dead back to life, to superimpose the supernatural on the real world and bring history into a concurrent dialogue with the present. What we feel in a given environment – the angle of the rain, the colour of the sky, the ‘tilt of the torn heath’ – can connect us to the ancient past through a sense of shared feeling and experience. Moreover, these were feelings and emotions that were more potent, more powerful, in Alfred’s day than they were in Chesterton’s or remain, indeed, in ours.

The Victorians loved Alfred. For the whole of the nineteenth century, and until – at least – the outbreak of the First World War, the Anglophone world (and white English males in particular) had a mania for crediting the West Saxon king with inventing almost everything that people in those days thought was a good idea – from Oxford University to the Royal Navy and from the British Parliament (and its colonial offspring) to the British Empire itself.34 He was a paragon of chivalry, of learning and wisdom, a Solomon-like figure, imbued with vast reserves of energy and prowess – a reformer of laws and, simultaneously, a conservative upholder of ancient traditions, a defender of the faith and a master of self-restraint, a scholar, a builder, a man of the people, a sufferer, a redeemer, a mighty warrior and ‘the ideal Englishman […] the embodiment of our civilization’.35 He was, in the words of the great historian of the Norman Conquest, E. A. Freeman, nothing less than the ‘the most perfect character in history’.36

To illuminate all of the extraordinary contortions, elisions, exaggerations, falsifications, misunderstandings, credulity, hyperbole, political expediency and mischief that collided in the creation of this absurdly hypertrophic idea of kingship would take us on a long detour from our intended destination.37 However, even though Alfred’s greatest achievement may have been the skill with which he publicized his achievements, like most myths his greatness is rooted in a certain amount of truth: for none of it – neither deserved fame nor inflated hero-cult – would have accrued to Alfred had he not found the wherewithal to fight himself out of the corner into which he had been painted in the spring of 878. Even with the knowledge that our view of Alfred derives from the ‘authorized’ version of his life, the mythic quality of its resurrection narrative lends something truly epic, cinematic in its emotional charge, to the return of the king.

In Alfred’s victory over Guthrum at Edington there is something of what Tolkien called ‘eucatastrophe’, the cathartic joy of a victory attained, against expectation, in the face of horror and despair. In his view, the archetypal eucatastrophe was found in the death and resurrection of Christ, a story that obtained its extraordinary power from its status as what Tolkien called ‘true myth’ – the entwining, as he saw it, of the strands of history and fairy-tale into the defining cable of truth running through the centre of human experience.38 It was this that caused him to insist – most famously to C. S. Lewis in discussions which ultimately caused the latter to reject the atheism of his youth – that myths, of all kinds (but ‘northern’ myths in particular), were not lies: they were echoes of mankind’s understanding of the one true myth that shaped all of humanity’s creative endeavour. To some degree this was a self-justificatory argument: Tolkien was ever anxious to reconcile his love of myth and fairy-tale – and his own lifelong creation of them – with a profoundly held Catholic faith.39

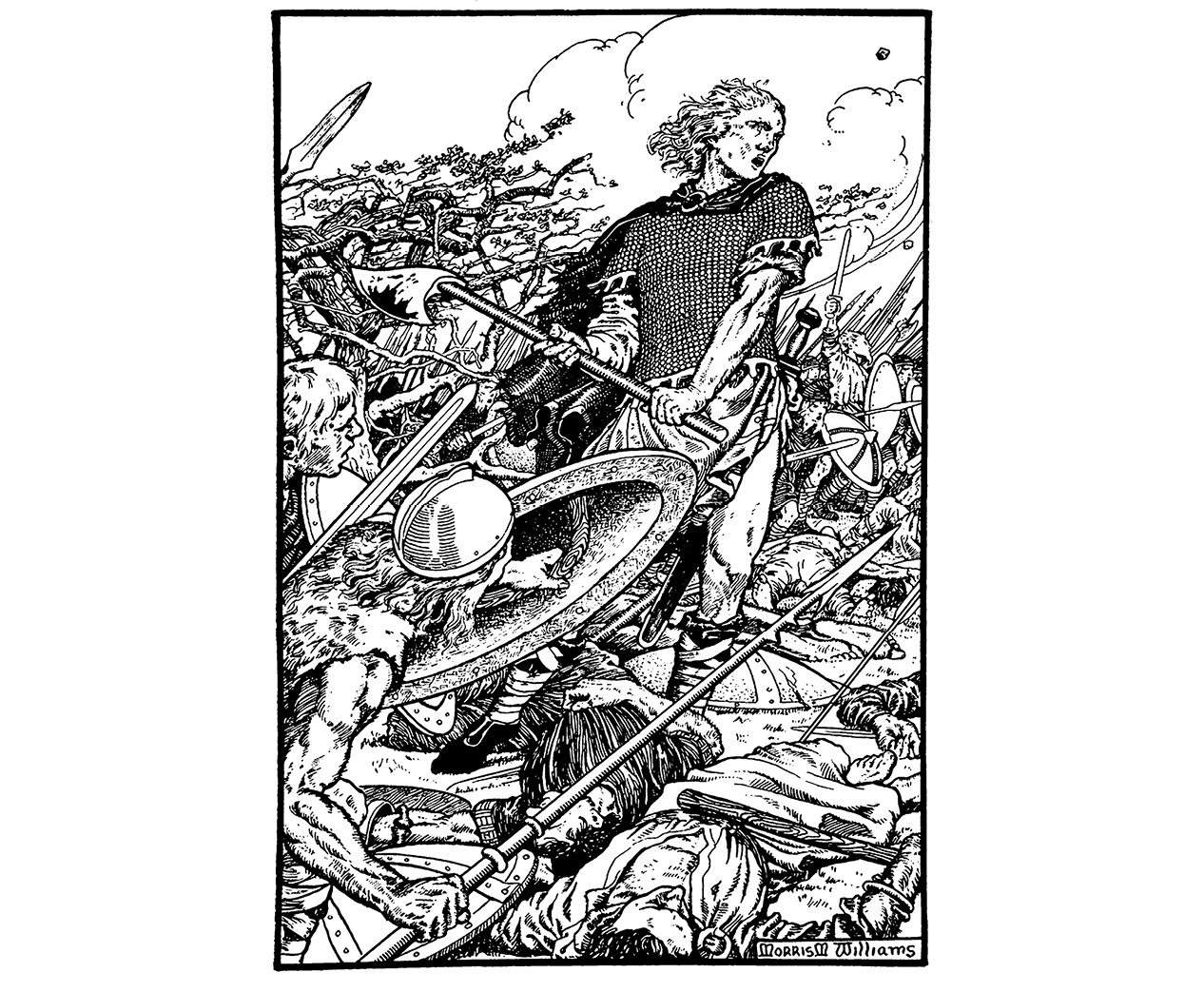

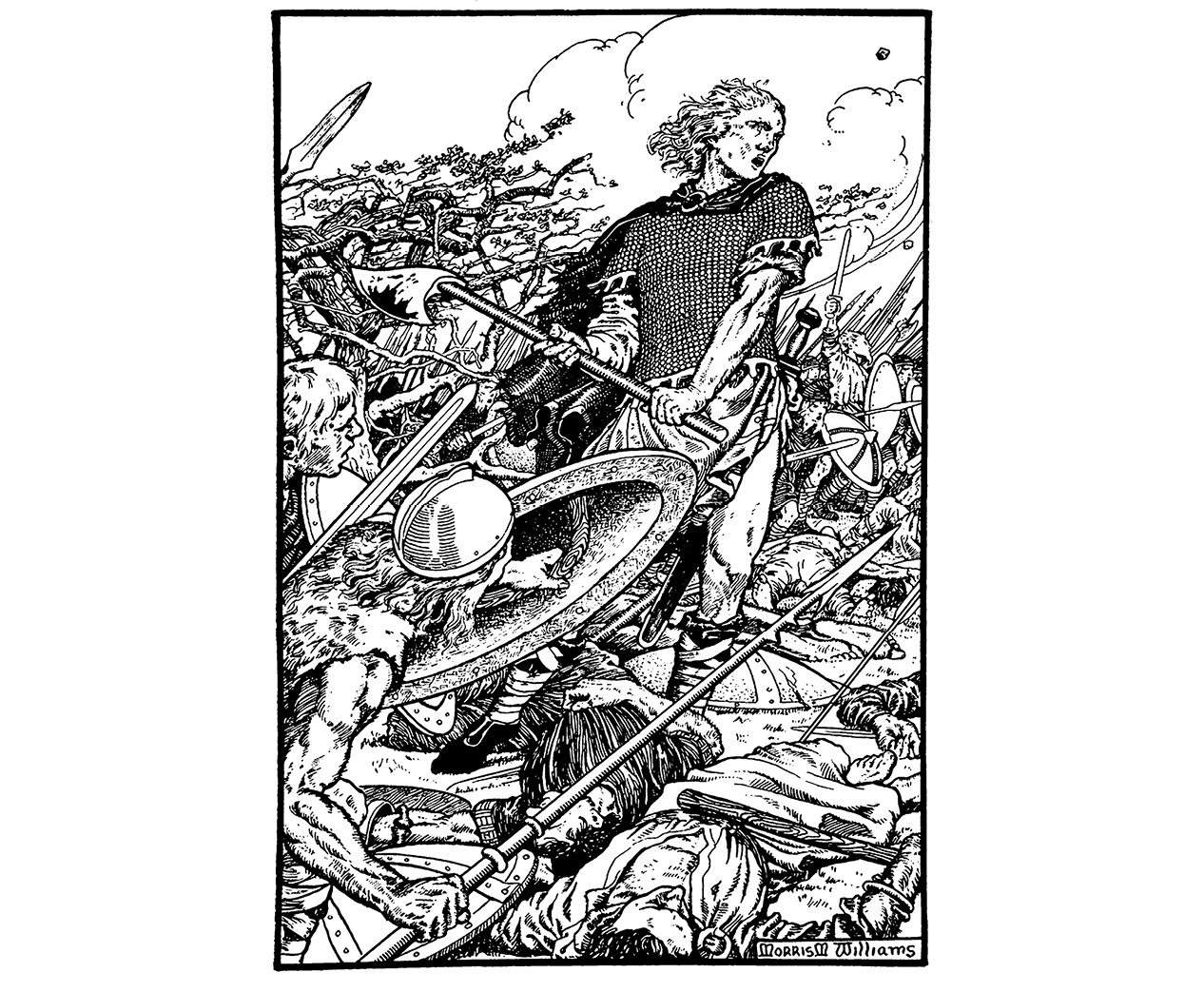

Alfred the hero, as envisioned by Morris Meredith Williams, 1913 (Photo © Historical Picture Archive/Corbis/Corbis via Getty Images)

In essence, however, these were not original thoughts, even if Professor Tolkien expressed them in ways which have retained a rare power. G. K. Chesterton himself had made very similar arguments in a public spat with the atheist and political activist Robert Blatchford in 1904.40 Chesterton had also recognized the mythic potency of Alfred, composing the weird but remarkable Ballad of the White Horse in 1911, one year after his disquisition on the floating shade of ‘Ethandune’. The Ballad comprises 2,684 lines of epic verse that tell the story of the king’s return from Athelney to triumph at Edington.41 It has been described as the high water mark of Victorian Alfredianism, as well as its effective epitaph,42 and it is hard not to see, in the power it draws from landscape and mythic archetype, a prefiguring of Tolkien’s oeuvre – even though the professor, while admiring the ‘brilliant smash and glitter’ of its language, was characteristically scathing about its merits overall (another demonstration of his tendency to attack more harshly those things which disappointed him than those that simply didn’t interest him: ‘not as good as I thought […] the ending is absurd […] G.K.C. knew nothing whatever about the “North”, heathen or Christian’).43

In the Ballad, the action of the battle is transposed to the landscape around the Uffington White Horse – a location which, as we have seen, is much more likely to have been the location of Alfred’s battle at Ashdown. But the Ballad is not about historical reality; the poem is filled with fictional details and improbable symbolism, designed to emphasize Alfred’s Christlike journey from ‘death’ in exile, to resurrection and apotheosis. It recognizes – or, rather, seeks to revive and recast – the story of these few weeks in 878 as the creation not only of Alfred’s personal myth, but of the nation itself, of ‘Englishness’ and, by extension, of ‘Britishness’ in its Anglocentric imperial iteration, born in a single moment of transcendent bloodshed that washed away the regional differences and ethnic animus of centuries. Chesterton’s three central protagonists, Alfred aside, were an Anglo-Saxon, a Briton and, most anachronistically of all, a Roman – three heroic avatars of what he evidently regarded as the progenitive peoples of (southern) Britain. In his view the Vikings were not part of this heritage:

The Northmen came about our land

A Christless chivalry:

Who knew not of the arch or pen,

Great, beautiful half-witted men

From the sunrise and the sea.

Misshapen ships stood on the deep

Full of strange gold and fire,

And hairy men, as huge as sin

With horned heads, came wading in

Through the long, low sea-mire.

Our towns were shaken of tall kings

With scarlet beards like blood:

The world turned empty where they trod,

They took the kindly cross of God

And cut it up for wood.

Chesterton’s ‘Northmen’ are dead-eyed, dim-witted barbarians – vital and potent, but a force of nature unfeeling as the storm-wind. They are the primal and impersonal tide against which the quality of Alfred’s humanity could be measured, a mute anvil upon which the gilt mantle of his greatness could be hammered out and the shape of the English nation forged. Of such stuff is national mythology built, and Alfred and his descendants themselves ensured that the events of 878 would be remembered in this light.

But, of course, nothing is ever so simple.