17

axe-age, sword-axe, shields are sundered;

wind-age, wolf-age, before the world crumbles:

no man shall spare another

Völuspá1

She walks away from the fire, eyes glassy, empty as ozone, walking slowly towards the west, into the weak sun and the wind and the cold sea spray and the rain, away from the world. Bare white feet press the black soil and broken turf, climbing the mound, dark and damp – an unhealed wound. The old woman is singing, a cracked calling, like the gulls.

The grave lies open, and she kneels. Thunder breaks out; ash on linden. And harsh voices, men’s voices; a dog barks, a horse screams.

And screams.

Below the ashes the sleeper sleeps on, sword under soil, spear under stone. Blood steeps the earth, stains the white sand. Ashes close the mound.

Above it all a pillar stands, cut from wood, one eye watching,

Facing the sea.

At some point in the tenth century, a man was buried at Ballateare on the Isle of Man.2 We don’t know where he came from, or who his ancestors were, only that he was buried in the manner of the heathen, like a Viking. Dressed in a cloak fastened with a ringed pin, he was laid in a coffin at the bottom of a deep grave. By his side was a sword, its hilt decorated with inlay of silver and copper. It had been broken and replaced in its scabbard. At his feet was a spear. It too had been broken. Around his neck a knife was hung, and a shield placed upon his body. Then the coffin was closed. Spears were placed upon the coffin, their points pointing towards his feet, and the grave was filled with white sand. Above the sand a mound was raised, cut blocks of turf stacked one on top of the other. Later a grave was dug in the top of the mound. A woman was buried there, face down, arms above her head; the top of her head sliced off with a sword. Nothing accompanied her in the grave, but the mound was sealed with the burnt remains of a horse, a dog, a sheep and an ox. A pillar was raised on top.3 No one can say what the nature of this pillar was. It may have been an elaborate beast-headed carving like one of the five enigmatic objects buried with the Norwegian Oseberg ship,4 or something like the ‘great wooden post stuck in the ground with a face like that of a man’ that ibn Fadlan described among the Rūs.5 However, the presence at Ballateare of what appear to be sacrificial remains chimes with references to the use of wooden posts in the context of other sacrificial offerings.

The ritualized killing of a slave in order that she might accompany her owner in death has been described already, and the Ballateare grave, along with a number of Scandinavian burials, has long been held up as evidence for the killing of humans (as well as animals) in the rituals surrounding the burial of ‘Viking’ elites.6 This interpretation of the evidence is not universally accepted, and there are a number of other possible explanations. The most interesting, but the hardest to prove, is the idea that the woman had died before the blow to the head, and that this had been administered after death in order to release the evil spirits trapped inside.7 It is also possible that the woman buried here was the victim of a judicial killing – that is, an execution – rather than a sacrifice, although whether this is a substantive distinction is moot. The association of the graves of criminals with prehistoric monuments, including burial mounds, is well established in Anglo-Saxon England.8 Such burials are often characterized by the unusual position of the body – often buried face down – as well as by evidence of severe corporal trauma. Sometimes it seems (again, in England) that posts were erected to display parts of the victim, especially the head (the OE phrase heofod stoccan – ‘head stakes’ – occurs sixteen times in English charters).9 However, the cremated remains of animals that were interred above the woman’s body at Ballateare imply that her burial was part of an event that involved multiple killings and burials – of animals as well as a human being. Whether or not this woman died to feed the grave, the evidence for elaborate death-theatre is strong and entirely in keeping with the multifarious rites that crowd the mortuary record in the Viking ‘homelands’.10

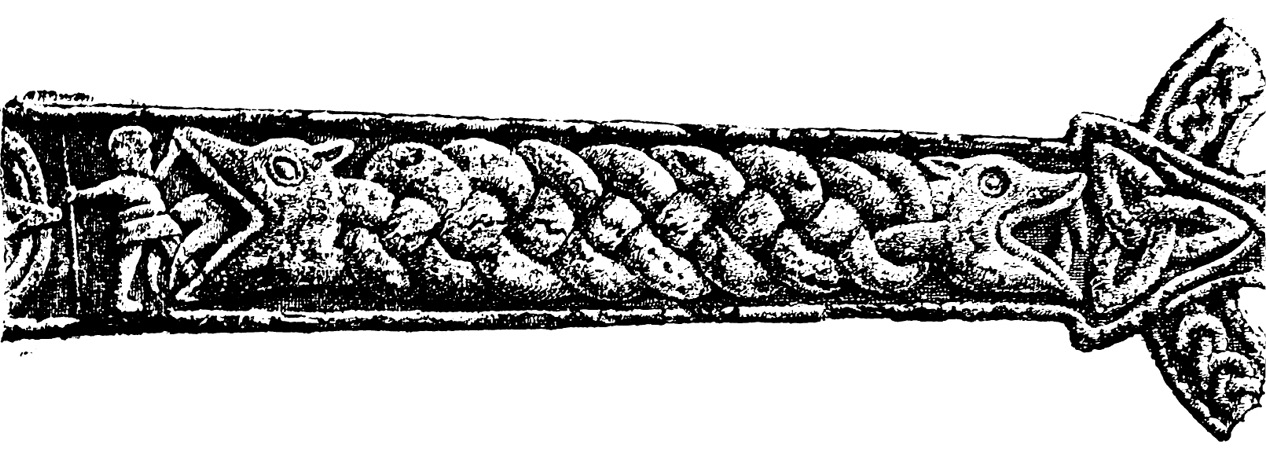

One might get the impression, if this were the only sort of evidence we had, that the role of women in the pagan Viking world was an unhappy one, where a likely fate was to be murdered and thrown face down into the grave of a male warrior, one more possession among the other icons of dominance and machismo with which such individuals were wont to be interred. For some women, slaves in particular, such may well have been their fate; but it is also true that such burials are rare and that the evidence for the treatment of women in death was as varied, as enigmatic and often as spectacular as the burial of any male warrior of the age. In fact, the most famous and splendid Viking burial ever discovered – the famous ship burial excavated at Oseberg near Oslo in 1904–5 – contained the bodies of two women, one elderly and the other in late middle age. The ship itself is one of the greatest treasures of the Viking Age, a vessel 70 feet in length, its prow crawling with creatures carved in an interwoven chain of sinuous movement. It dominated the burial, forming the stage on which the dramaturgy of death was performed and the framework for the earthen mound which eventually submerged it.11 To see beyond it, however, is to be staggered by what the rest of this mighty tomb once concealed. There is no adequate way to convey in words the quality of the objects that were placed in the grave, their weird beauty, the strange carved faces that peer from the sides of the wooden wagon, or the elaborate three-dimensional beast-head pillars that served no purpose that any scholar has been able convincingly to propose.

But the quantity! This is easier to indicate. I reproduce below the inventory published by the Norwegian Museum of Cultural History:

2 women; 2 cows; 15 horses; 6 dogs; 1 ship; oars; rope; rigging equipment; remnants of sails; 1 hand bailer; 1 anchor; 1 cart; 3 ornate sleighs; 1 work sleigh; 2 tents; 1 framework for a ‘booth’, with walls of textile; 3 long combs; 7 glass beads, 4 with gold inlay; 2 pairs of shoes; 1 small leather pouch containing cannabis; several dresses and other garments; feather mattress; bedlinen; 2 pieces of flint; 5 animal head posts; 4 rattles; 1 piece of wood, arrow-shaped, approx. 40cm long; 1 round pole with a runic inscription, approx. 2.40m long; 1 leather band, knotted like a tie; 1 burial chamber; 1 approx. 1m long wooden pipe; 1 chair; 6 beds; 1 stool; 2 oil-burning lamps; 1 bast mat; 3 large chests; several smaller chests, boxes and round wooden containers with a lid, used mainly for storing food; 3 large barrels; 1 woven basket; 1 wooden bucket with brass fittings; 1 wooden bucket with a ‘buddha’ figure; 1 small staved bucket made of yew wood; 3 iron pots; 1 pot stand; several stirring sticks and wooden spoons; 5 ladles; 1 frying pan; 1 approx. 2m long trough; 1 earthenware basin; 3 small troughs; 7 wooden bowls; 4 wooden platters; 10 ordinary buckets (one containing blueberries); 2 work axes; 3 knives; 1 quern-stone; bread dough; plums; apples; blueberries; various woollen, linen and silk textiles; 1 large tapestry; 5 different weaving looms; 1 tablet weaving loom; 1 manual spindle and distaff; various small tools for spinning and textile work; 1 device for winding wool; 2 yarn reels; 2 linen smoothers; 1 smoothing iron; 3 wooden needles; 1 pair of iron scissors; 2 washing paddles; 1 round wooden container with a lid, used mainly for storing food; 5 balls of wool; 1 weaving reed; piece of wax; 3 small wooden bowls; 1 small quartz stone; 3 pyrite crystals; 2 slate whetstones; 1 knife handle; 1 bone comb; 1 small wooden bowl; 18 spades (probably belonged to the grave robbers); 1 dung fork; 3 grub hoes; 2 whetstones; 2 awls; 3–5 caskets; 5 wooden pins used to drape things; 1 horsewhip; 1 saddle; various kinds of harness fittings; 5 winter horse shoes of iron; several small wooden pegs for tethering horses; several dog chains of iron; mounts for several dog collars.12

An attentive reader of this list may notice a striking absence. There is nothing, at all, of silver or gold, no jewellery, no gemstones, no amber beads or brooches, no pendants, coins or neck-rings, no gilded bridle mounts or hammered bracteates: none of the things, in short, that characterize other high-status Scandinavian graves, male and female, of similar and earlier antiquity. They will also have noted the presence of ‘18 spades [which] probably belonged to the grave robbers’.13 These were not modern spades; the mound was disturbed long ago – not long, in fact, after it was closed – and the absence of precious metal objects is probably attributable to this ancient tomb-raiding. (Exactly why the grave was disturbed remains a matter for debate – the scale of the excavation required would have been difficult to manage covertly and may have been sanctioned in some way. Illicit grave-robbing was, in any case, a risky business. Later generations of Norse-speakers were fascinated by the trouble that opened graves could bring down on the heads of intruders – witting or unwitting.) The extraordinary inventory of finds from the Oseberg burial thus represents the left-overs, the picked carcass – the stuff that was too cruddy or too bulky to bother with. In its pristine condition, the burial chamber of the Oseberg grave must have been an astonishing sight, its principal occupant a Nefertiti of the North Sea littoral, buried in a grave to make Sutton Hoo look like Sutton ‘whatever’.

Viking ship burials are known from Britain, though nothing on this scale. Nevertheless, whenever a community chose to treat its dead in this way it represented a very public and conspicuous disposal of wealth: a bit like burying a loved one in a car. Anyone so buried, however modest it may seem relative to the Oseberg burial, was being honoured as an important player within the community. One such man was excavated at Ardnamurchan (Scotland) in 2011; his was the first complete boat burial ever to be found on the British mainland. He was buried with sword, axe, spear and shield, laid out in a boat 16 feet in length; in death, he presents the image of a wealthy and powerful pagan warrior, a warlord of the ocean’s edge, equipped to pursue a life of adventure on the dark waters of the hereafter. Other male boat burials have been found in the isles (at Colonsay, Oronsay and Orkney, and on the Isle of Man) and fragments of a boat grave – now lost – were found in 1935 at the site of the Huna Hotel in Caithness.14 At Westness cemetery on Rousay, Orkney, for example, two boat burials were excavated in the 1960s, and the boat graves of men have been found on Man at Balladoole and Knock-e-Dooney. In each case, the boats in which they were interred measured in the region of 13 to 16 feet – the size of the small oared boats that were interred as secondary grave goods in the burial mound of the Gokstad ship in Norway.15

It was not only men, however, who were afforded these extravagant death rituals in Britain. At Scar on Orkney a woman in her seventies – a fabulously advanced age for the time – was buried in a boat 25 feet long, alongside a man in his mid-thirties and a child.16 A whalebone ‘plaque’, a flat board of roughly rectangular shape, with a simple rope-like pattern cut into it at the borders and decorative roundels incised into its surface, was set at her feet. At one end, the shape of the board has been carved away to fashion the profile of two bestial heads on sinuous necks, spiralling to confront one another – teeth bared and tongues lolling. It is an iconic image of the Viking Age, but no one knows what objects like this were used for (a similar example can be found in the collection of the British Museum, excavated from another female boat burial in Norway). They were, however, possessions that not every woman in society could expect to be buried with. Possibly they were emblems of status, a symbol of the magical and religious powers that women in Viking society could wield. The other objects in the grave included the paraphernalia of weaving – spindle whorls and weaving sword, needle-case and shears. The processes and symbolism of weaving were far from mundane – they could, for some Viking women, provide the tools and imagery for hidden and terrible powers.

What is perhaps most important about overtly unChristian burial traditions like these is that they were drawing their material vocabulary from the practices of Viking Age Scandinavia: these were the graves of people and of communities who still felt themselves connected to a homeland from which they had been divorced, and their behaviour implies a desire to maintain a cultural link across space and time. The people who buried their matriarch at Scar were inserting her corpse into a tradition that included the women of the Oseberg burial, claiming for her a shared identity and tapestry of beliefs (the Oseberg burial also contained, on a lavish scale, a battery of equipment related to weaving and textile production). The same can be said of all the ‘pagan’ Viking graves of Britain – the mound at Ballateare and the cemetery at Westness, the barrow graves of Cumbria and the cremated remains of Heath Wood near Repton among many others.

As the hogbacks demonstrate, however, this conservatism was not to last. From almost the moment they arrived in Britain, new beliefs were shaping the way that the Vikings treated the dead and imagined the afterlife, and evolving identities and political realities were refashioning the way that British ‘Vikings’ found their place in the world. The old ways were dying fast.

First the snows will come, driving hard from all points of the compass; biting winds, shrill and screeching, bringing the cold that cuts. Thrice the winter comes, three times with no relenting; no spring will come, no summer to follow, winter upon winter, the land swallowed by ice unending. The green shoots will die under the frost, the skeleton trees creaking beneath the weight of snow – the world will fall dim and silent, shadowed in perpetual twilight. ‘Fimbulvetr’ they will call it, the ‘great winter’, and few will survive its corpse-grip. Those who do will wish that they had died.

Riding on the back of the ice-wind, sweeping down paths of famine and despair, war will sweep the ice-bound world, violence shattering families, severing oaths – ‘brothers will struggle and slaughter each other, and sisters’ sons spoil kinship’s bonds’. So the prophecy runs. And as the axes rise and fall and all the blood of the earth is emptied out on to virgin snows, a howling will be heard away in the east.

Gods and elves will lament and hold council as their doom unfolds. Yggdrasil, the world tree, will shake and an uproar rumble from Jötunheimr; the dwarves will mutter before their doors of stone. For the time now is short before all bonds are broken, and the wolves of Fenrir’s line, the troll-wives’ brood, will break free from the Iron Wood and run from the east. And they will swallow down the sun and swallow down the moon, and the heavens will be fouled with blood.

Then the Gjallarhorn will sound, the breath of Heimdallr, watchman of the gods, echoing across the worlds, its blast echoing from the mountains. It shall awaken the gods and the einherjar – the glorious dead – and they will assemble and make themselves ready for the final battle, Odin speaking with Mímir’s head for final words of counsel. For their foes shall have already arrived and will stand arrayed in dreadful splendour upon the battle plain, the field that runs for a hundred leagues in all directions – a bleak and boundless tundra.

There shall come Loki, father of lies, freed from an age of torments; and with him will stand his terrible children: Fenrir, the wolf, his mouth gaping wide enough to swallow the world, fire spewing from his eyes; and Jormungandr, the world serpent, shall haul his foul coils on to the land, writhing and thrashing, venom gushing. To this place, too, shall the giant Hrym come, he will steer the ship of dead men’s nails to this place of reckonings, leading the frost giants on to the battle plain. Last to arrive will be the sons of Muspell, the flaming hordes marshalled by Surt, demon of fire, his shining sword setting all ablaze beneath the riven sky.

And Odin will ride to meet them at the head of his host, gripping the spear, Gungnir, forged by the sons of Ivaldi; and he will wear a helmet of gold and a coat of mail. Thor will be with him and Frey and Tyr and Heimdall, and all those heroes who died in battle and were chosen.

And all will fall.

This was how the Vikings imagined the world would end,17 shattered in the madness of battle, poured out in the blood of the gods on Vigrid – the ‘battle plain’. It would die with the thrashing coils of the serpent, the sun devoured, the earth burned away – choked out in torrents of ice and fire, the way it had begun. The story of Ragnarök – the ‘doom of the gods’ – is recorded in two complete versions, the eddic poem Völuspá and a prose account compiled by Snorri Sturluson in the mythological handbook Gylfaginning, for which Völuspá was the primary source. Völuspá means ‘the prophecy of the völva’ – the seeress. It is a prophetic poem delivered to Odin, a telling of the great arc of mythic time, from the world’s beginnings in the void to its breaking at Ragnarök and its subsequent rebirth. It is the ultimate encapsulation of the knowledge that Odin seeks, the knowledge for which he has sacrificed himself to himself, for which he has given his eye and taken the head of Mímir. It offers cold comfort.

Odin will ride into the jaws of Fenrir and do battle with the wolf; he will face it alone, and that will be the end of him, the All-Father swallowed into the maw of death. Thor will ride beside him, but no help will come from that quarter. Thor will be locked in deadly conflict with Jormungandr and, though he will slay the wyrm, he will be poisoned by its venom – staggering nine steps before he too will fall. Frey will die also, cut down by Surt’s flaming sword. Tyr, the one-handed god, will go down to Garm – the hound who howls before hell’s mouth – and Heimdall and Loki will slay each other.

The ideas contained in Völuspá, and rationalized and repeated by Snorri, cannot be attributed with any confidence to the Viking Age itself, but allusions to, and scenes from, the story of Ragnarök are found in other poems and fragments.18 Of these, two of the most dramatic are found carved in Britain, shards of the pagan Viking end of days, frozen in immortal rock.

Thirty-one runestones stand on the Isle of Man, the largest number in any place outside Scandinavia. Like their cousins, they are memorials to the dead (although at least one was erected to salve the soul of a living man) and are defined by the runic carvings – inscribed in the Norse language – that record the names of those lost and those remaining, and the people who raised the stones. (Some also carry inscriptions in Ogham, the vertical Celtic alphabet of hatch-marks used in Ireland and western Britain – a sure sign of a culturally and linguistically mixed population.)19 They make up roughly a third of all the carved stones of Man, an impressive corpus of sculpture bearing the combined influence of Irish stoneworking traditions and Scandinavian art-styles. They are, stylistically, quite dissimilar to the runestone tradition of the Viking ‘homelands’ and are primarily cruciform objects – either high standing crosses, or cross-incised slabs akin to the Christian symbol stones of Pictavia.20 The inscriptions they carry are, for the most part, fairly mundane, although they do provide a thrilling glimpse of the individuals who peopled Viking Age Man, even if the light that the inscriptions cast on these people is but a fleeting glimmer in the dark.

‘Þorleifr the Neck raised this cross in memory of Fiak, his son, Hafr’s brother’s son,’ runs the inscription on the tenth-century standing cross at Braddan Church;21 ‘Sandulfr the Black erected this cross in memory of Arinbjǫrg his wife …’ runs another at Andreas Church.22 Some, like Þorleifr’s, hint at premature tragedy (‘Áleifr […] raised this cross in memory of Ulfr, his son’),23 another acknowledges a guilty conscience (‘Melbrigði [incidentally, the same Celtic name (albeit spelled differently) as that scratched into the back of the Hunterston Brooch], the son of Aðakán the Smith, raised this cross for his sin …’) but concludes with the prideful boast of the rune-carver (‘but Gautr made this and all in Man’).24 Sometimes they hint at familial drama and community tensions. A person who identified himself as ‘Mallymkun’ raised a cross in memory of ‘Malmury’, his foster-mother. He ends with the sour observation that ‘[it] is better to leave a good foster-son than a wretched son’. A thousand years later, the rancour still festers in the stone. Other thoughts are snapped off by time and left hanging: ‘Oddr raised this cross in memory of Frakki, his father, but …’25 But what? It is most likely that the missing runes revealed the name of the carver (‘but [so-and-so] cut/made this’ is a typical formula), but it is impossible to rule out a more personal aside: ‘… but Hrosketill betrayed the faith of his sworn confederate’,26 runs the truncated inscription on another stone at Braddan Church. Alas, what Hrosketill did – or to whom, or even for what purpose the stone was raised – is lost for ever.

The most famous of the Manx runestones is the fragment of a monument known as ‘Thorwald’s Cross’, found at Andreas Church. It is a slab-type runestone, with its surviving inscription ‘Þorvaldr raised [this] cross’ running down one edge, and a decorative cross on each face, embellished with characteristically Scandinavian ring-chain carvings. In the case of this particular runestone, however, the simple Christian message is complicated by the subject matter to which the carver chose to turn his chisel. On one side of what remains of the stone, cut in relief on the bottom right-hand quadrant left vacant by the cross, is the image of a male, bearded figure with a large bird perched upon his shoulder. A spear is in his hand, its point downwards, thrusting towards the open jaws of a wolf – a wolf that is in the process of devouring him, his right leg disappearing down the lupine gullet. There can be little doubt that this is a depiction of Odin, Gungnir in hand and raven on his shoulder,27 swallowed by the wolf.

Across the sea from Man, at Gosforth in Cumbria, a tall cross stands in the churchyard of St Mary’s, 15 feet of slender masonry with pea-green lichen clinging like sea-scum to the ruddy Cumbrian stone. It seems odd and incongruous, standing there amid the dour eighteenth-century tombstones – like some strange Atlantean pillar recovered from the ocean floor and hauled upright, flotsam from another world. Its carvings are in surprisingly good condition, given the millennium during which it has stood against the elements. The lichen is less ancient than the carvings it obscures. In 1881, Dr Charles Arundel Parker – the obstetrician and part-time antiquarian – and his friend the Rev. W. S. Calverley came to Gosforth ‘one dull wet day in the late autumn’, when, the two gentlemen had determined, ‘the continuous damp and rain of the previous weeks would have softened the lichens which had filled every sculptured hollow’. Happily for them and the condition of their frockcoats, these were days when menial labour was easily to be had. These two learned fellows stood in the churchyard while Dr Parker’s coachman, ‘up aloft, with a dash of a wet brush to the right and to the left hand scattered the softened mosses’.28 What he revealed were the triquetrae (interlacing triple-arches) that decorated the cross-head, the final details to be revealed and recorded of a monument that boasts the most comprehensive iconographic depiction of Norse mythology dating to the Viking Age anywhere in Europe.

Many of the scenes that cover the four faces of the shaft of the Gosforth Cross remain open to interpretation, but two in particular stand out. One is the torment of Loki, the punishment inflicted for his part in the death of Baldr and the pivotal event of the mythic cycle that ends with Ragnarök. We see him bound in an ovoid cell, a pathetic trussed creature, while his wife Sigyn bends over him to catch the venom that drips from the serpent pressing its diamond head into his face. The other is the depiction of a figure, striding purposefully into the gaping mouth of a beast, one foot upon the lower jaw, one hand reaching to grip the upper, a spear held in the other. Snorri provides the key that enables us to identify this figure as Vidar, son of Odin: ‘Vidar will stride forward and thrust one of his feet into the lower jaw of the wolf […] With one hand he takes hold of the wolf’s upper jaw and rips apart its mouth, and this will be the wolf’s death.’29 This is the end of the wolf, Fenrir, but it is not the end of the world. That comes with the final blackening of the heavens and the burning of Yggdrasil, the sinking of the earth into the sea – a return to the primeval void.

In all tellings of the Ragnarök story, however, there is a final act, a light to guide us through the darkness. In Völuspá it is told with heartbreaking simplicity, the heathen völva’s vision of a far green country – a promised land to come:

She sees rising up a second time

the earth from the ocean, ever-green;

the cataracts tumble, an eagle flies above,

hunting fish along the fell.30

There are aspects of this unfolding vision that feel familiar – the ‘hall standing, more beautiful than the sun, better than gold’, where ‘virtuous folk shall live’ and ‘enjoy pleasure the live-long day’ and, in one version of Völuspá, the sudden appearance of ‘the mighty one down from above, the strong one, who governs everything’,31 the arrival – as one scholar describes it – ‘of Christ in majesty, descending to the earth after the rule of the pagan gods has come to an end’.32 This Christian coda to the pagan end of days is there at Gosforth as well, more explicitly perhaps than anywhere else. Immediately below the depiction of Vidar’s grisly dispatch of Fenrir is a depiction of the crucifixion, the redemptive fulcrum of human history – the event which, in Christian cosmology, ensured safe harbour for the souls of those who embraced its message. It is the symbol of the promise of eternal life, the seal that guarantees that a new world shall rise from the ocean.

Vidar and Fenrir on the Gosforth Cross; Julius Magnus Petersen, 1913 (Wikimedia Commons)

It is a supreme irony that the very monuments at Andreas Church and Gosforth which seem to confirm the pagan beliefs written down in a later age also bear witness to their dwindling, their co-option into a new world-view. The old stories were not yet dead at the time these monuments were made, and many of them would never die, living on through the versions written down 300 years after being alluded to in stone. But by this time the stories were no longer (if they ever were) an oppositional belief system, a Viking ‘religion’ to rival the teachings of the gospel. They were, instead, passing into folklore, becoming tales that could be told without threatening the Christian world-view, complementing it perhaps, explanatory metaphors for the new narratives that were percolating through mixed and immigrant communities. We might imagine that it would, initially, have been easy for a people accustomed to many gods to add another to the throng (or many others – the trinity and the multitudes of saints and angels would doubtless have appeared indistinguishable at first from the gods, ghosts and elves of native belief). Over time, the exclusive nature of the Christian god would have gradually asserted itself, but it cannot have been clear at the beginning. The crosses at Gosforth and Andreas Church can therefore be interpreted in different ways as the products of an incomplete conversion – made for or by people for whom, at the time, Christianity was just an additional set of images and stories to add to the mythological cauldron.

On the other hand, perhaps, these were erudite attempts to juxtapose Christian and pagan images – a means of instructing new converts on the essentials of the Christian faith. For example, although the scene on the reverse of Thorwald’s Cross has not been securely interpreted, there is little doubt of its Christian intent: a man wielding a huge cross and a book tramples on a serpent while another Christian symbol, a fish, hovers near by: a triple whammy of Christian symbology. There is room for a little ambiguity here – crosses can easily be mistaken for hammers (indeed, some Thor’s-hammer pendants may actually have been intended as crosses, and some deliberately combine cross and hammer on the same object),33 and Thor was famous as both a fisherman and a fighter of serpents. One thing he was not, however, was bookish, and it is this more than anything else that gives the Christian game away. Although we cannot know for sure, it may be that the missing ‘panels’ of the complete cross depicted complementary images from pagan and Christian mythology – a sort of pictorial instruction manual to Christianity, the build-it-yourself guide to getting religion with the old myths deployed as the key.

I prefer, however, to see all of this in a different light, to see the Ragnarök story as an expression of a melancholy self-awareness, the creative and emotionally profound product of people who could feel the old world slipping away, a poetic response in words and stone to the twilight of an ancient way of life, a twilight of their gods. The Ragnarök story brims with sadness and nostalgia, a pagan vision of the future that was alive to the impending extinction of its own world-view in an increasingly homogenized Europe. It is a complex and intellectually involved interplay of hope and defeat, defiance and resignation, an acknowledgement – a recapitulation – of what was already slipping away and a yearning for a new and better world around the corner. For the Viking communities of Britain, that hope lay in the new identities and new ways of being that were being adopted and adapted in different ways across the islands. As the tenth century progressed, old affinities and beliefs began to break down as new political and cultural realities asserted themselves. What it meant to be a ‘Viking’ in Britain was changing rapidly.34