IDA B. WELLS, THE ANTILYNCHING MOVEMENT, AND THE POLITICS OF SEEING

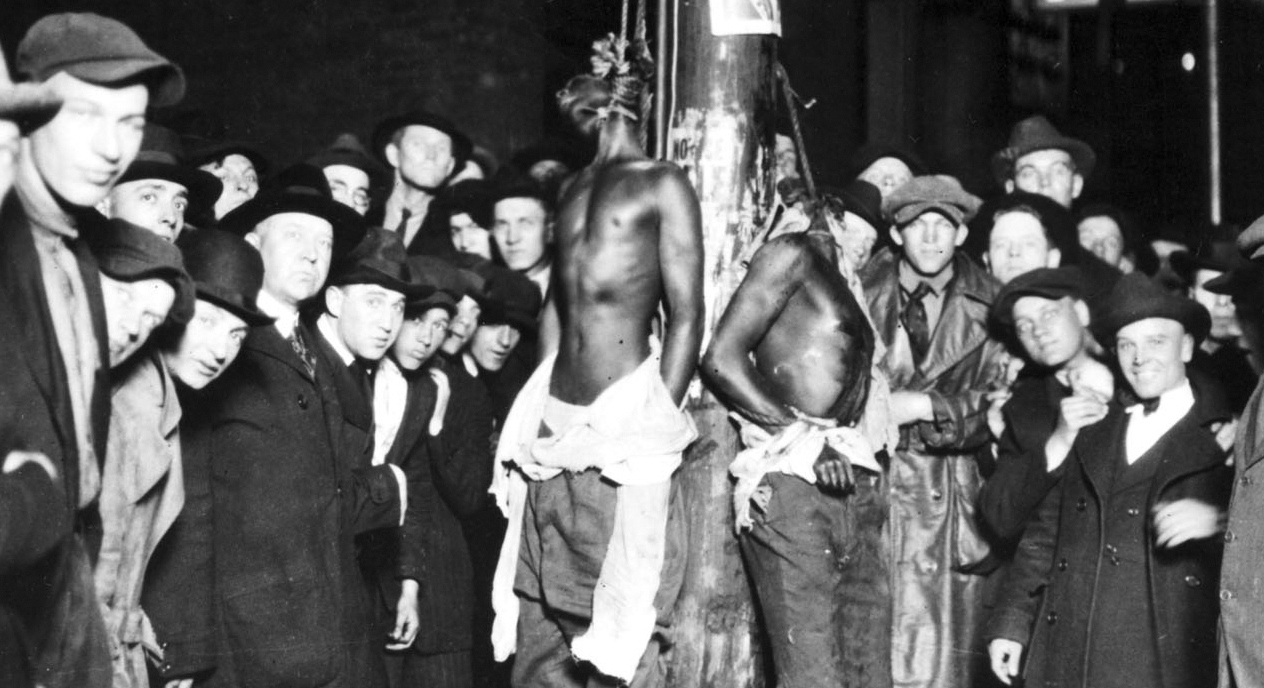

On June 15, 1920, in Duluth, Minnesota, a photograph, which eventually became a widely circulated postcard, captured a crowd of white men smiling for a camera, beside the lifeless and shirtless bodies of two black men hanged from a lamppost; a third lay face down on the ground. Though this lynching was one of the most infamous and gruesome, it was just one of over three thousand, from 1890 through 1930, enacted by white citizens and directed toward black men. Lynching was a horrifying practice that seemed beyond the pale of human imagination. But it had a real social function: to solidify the rule of white supremacy and instill fear in black Americans like Elias Clayton, Elmer Jackson, and Isaac McGhie, who arrived in Duluth as part of a traveling circus. Nat Turner would be executed for a direct act of public resistance to slavery almost ninety years earlier. These workers had done no such thing.1

The justification for their lynching was also the culturally dominant one: that black men were raping white women behind closed doors. Time and time again—and in the Duluth case—this justification was revealed to be baseless, a product of white, male, racist fantasies. Yet lynchers also used other justifications, ranging from major allegations like murder to minor ones like burglary, so-called race prejudice, making threats, rioting, and being irreverent to authority. Most perplexing of all, lynching was sometimes committed with no overt reason in mind, as if to suggest that the murder of black people did not even require justification.2

FIGURE 2.1 Postcard photograph of June 15, 1920, Duluth lynchings.

Source: Image from Minnesota Public Radio, http://news.minnesota.publicradio.org/projects/2001/06/lynching/olli.shtml.

The Duluth photograph conveys that lynching was a national moral and political problem, one that exceeded the geographic area of the American South, where it happened most frequently.3 The smiles of the onlookers—as they surround the three dead black bodies—facing the camera not only revealed the unimaginable darkness of the human condition but also brazenly posed two questions to many whites across the nation. Will you really punish us for protecting the honor of our women and our way of life on behalf of our community, even if this is done in such a gruesome way? If push came to shove, wouldn’t you do the same? The federal government’s failure to pass antilynching legislation proved that the answer to the first question was a resounding no. And the public support of many newspapers in defense of lynching throughout the country—which itself reflected the tacit support of this ritual in many segments of the American population—testified that the answer to the second was a resounding yes.

Not all Americans felt similarly. This chapter will discuss someone who devoted her lifework to raising consciousness about lynching and in doing so became one of the most important activist-intellectuals in American history: the African American journalist Ida B. Wells-Barnett. Born to enslaved parents in Holly Springs, Mississippi, in 1862, Wells came to public prominence when, in 1884, she directly resisted the “separate but equal” segregationist logic behind Plessy v. Ferguson (1896) a decade before it was decided by the U.S. Supreme Court, by refusing to give up her seat in the “ladies car” of a railroad in Tennessee after she was told by the train’s conductor to go to the rear car, designated for “smokers.” Then, after one of her black friends, Thomas Moss, was lynched in Memphis in 1892, Wells become a militant antilynching activist, fusing investigative reporting with the burgeoning field of social science to argue that lynching was a form of vigilante justice that desecrated American cultural commitments to the rule of law. Wrong were those who thought lynching was nothing more than a misguided attempt to enforce antiquated, if not frivolous, codes of Southern chivalry enacted by uneducated masses who foolishly believed the machinery of justice was just too slow and procedural to mete out swift punishments.

Wells theorized lynching as a form of racial terrorism aimed against the black community. Her analysis gave way to a progressive political agenda in which Wells attempted to persuade American lawmakers that lynching was a national crime that required national legislation. Wells’s words and deeds made it clear that no American, especially no African American intellectual, could stand by idly as black people were murdered in cold blood.

Historians rightly characterize Wells as an exemplary black woman activist who rendered dubious American gender norms and spoke truth to white supremacy and whose words unsettled apathetic American citizens and the political leaders they elected.4 Others take her to be unique for pushing the boundaries of the black intellectual.5 Substituting the call for racial accommodation and personal uplift with one of direct political engagement made her the anti–Booker T. Washington. Doing this in an impassioned manner made her an uncompromising version of W. E. B. Du Bois, who—despite his later conversion to the radical ideologies of pan-Africanism and communism—at the beginning of his career was still very much a race-conscious reformer who cared more about detached sociological work than about direct action.

But resisting American blindness toward lynching—as well as the culture of white supremacy upon which it depended—led her to revise key understandings of American citizenship. If devising a notion of citizenship capable of addressing the problem of action under immense constraint was at the heart of Douglass’s and Walker’s political thought, then nothing concerned Wells more than developing an emancipatory conception of citizenship capable of countering the problem of extralegal violence in liberal-democratic regimes.

Lynching reflects three acute problems especially common to democracy, a system where “the people” are endowed authority to popular rule.6 First, there is the problem of vigilantism, where a group of people—irrespective of how much of a numerical minority they are—claim to speak for the entire people of which they are part and act on the basis of some unwritten law of popular sovereignty that threatens collective life. Second, there is the problem of passivity, where individuals and the government that they legitimize either maintain tacit consent or simply turn an apathetic eye toward injustice. Third, in democratic societies the idea of “the people” is always up for negotiation, and visual public spectacles are incredibly powerful for policing the boundaries of community by playing on citizens’ emotions such as fear or love.7 If we consider these problems as telling us something about the risks and unexpected implications of living a life in common with others, then we should also study the specific practices of citizenship—including the mode of action, that is, judgment and deliberation—that can help address them. Nothing preoccupied Wells more than outlining these practices, and the task of this chapter is to highlight them.

In Wells’s view, conceptions of democracy that didn’t account for the antidemocratic dimensions of instrumental thinking and popular sovereignty were to be rejected. A mode of political judgment that took seriously human complexity was to be embraced. Individuality needed to be reimagined as inviolable human dignity, and punishment needed to be seen from the perspective of its devastating moral effects, its impact on those who experienced it, and its cultural implications for democracy. Citizens needed to appreciate how public shame foreclosed democratic deliberation while recognizing that desire could remake one’s commitments and identities in emancipatory ways. Hope needed to be seen as persisting between realistic constraints and continuing to agitate for justice. Adopting these ideas and practices would not guarantee an end to violence or the achievement of democracy. But Wells insisted that they would be an important first step toward this goal.

BLACK WOMAN JOURNALIST

Walker and Douglass were often blind to gender, even if they were not so enamored with black masculinity in ways that led them to endorse black patriarchy. Wells cared deeply about gender equality. But the intensity of her support for expanding the political franchise across gender lines, like the suffragettes of her generation,8 was only matched by the regularity with which she invoked an essentialist definition of womanhood defined by bourgeois standards—of dutiful mother, meticulous homemaker, and loyal wife—endorsed by many nineteenth-century first-wave feminists. In “Woman’s Mission” (1885), she wrote, “no earthly name is so potent to move men’s hearts, is sweeter or dearer than that of mother.”9 She continued:

What is, or should be, woman? Not merely a bundle of flesh and bones, nor a fashion plate, a frivolous inanity, a soulless doll, a heartless coquette—but a strong, bright presence, thoroughly imbued with a sense of her mission on earth and a desire to fill it; an earnest, soulful being, laboring to fit herself for life’s duties and burdens, and bearing them faithfully when they do come; but a womanly woman for all that, upholding the banner and striving for the goal of a pure, bright womanhood through all vicissitudes and temptations.10

Wells grappled with the question posed by earlier white American feminists: how to construct an image of womanhood that rejects the tyranny of social convention when, paradoxically, social convention—however unjust—is precisely what endows many women with a sense of self and orientation in a male-dominated world.11 Her answer to this question was as troubling as it was a reflection of her culture. The religiously infused ideals of moral virtue, manifest destiny, and commitment to Western civilization she believed women needed to embody were used as justifications not only for lynching but also for the American imperial excursions of the early twentieth century led by Theodore Roosevelt; for the social work of the temperance advocate Frances Willard; and by the social democrat Jane Addams, who sought to make life livable for the other half—the working poor who were casualties of the massive economic inequality of the Gilded Age. At times, unreconstructed views about normative civilization, which infused Wells’s public shaming of white lynchers, themselves expressed overt racism. In the course of highlighting the brutality of lynching, she wrote that

the red Indian of the Western plains tied his prisoner to the stake, tortured him, and danced in fiendish glee while his victim writhed in the flames. His savage, untutored mind suggested no better way than that of wreaking vengeance upon those who had wronged him. These people knew nothing about Christianity and did not profess to follow its teachings; but such primary laws as they had they lived up to.12

But if misogynistic and racist views were not entirely undermined by Wells’s arguments, then they were extinguished through her political work as a political journalist, educator, activist, and public speaker at home and abroad in England. Fictitious was the patriarchic myth that a woman properly belonged to the realm of the household, under the supervision of her husband, because, to borrow a misogynistic argument of Aristotle’s in Politics, she did not have “authority” over the “deliberative faculty,” which was crucial for public life.13 Equally dubious, Wells’s activities demonstrated, was the view, to put it in words that Abraham Lincoln once used and that white supremacists would have endorsed, that people of color were “not equal” in “moral or intellectual endowment” to their white counterparts, who understood the virtues of citizenship in an exemplary way.14

Immersion in the black bourgeois circles of Memphis—where black culture and business were flourishing—led Wells to develop an ambivalent understanding of political leadership. At times, she echoed much of late nineteenth-century African American thought—ranging from the black nationalist Martin Delany and the pan-Africanist Alexander Crummell to the conservative Booker T. Washington—about the importance of black economic self-sufficiency, which required rugged individualism.15 The African American citizen, she wrote, “must be taught his power as an industrial and financial factor. He must be shown that the turning of his money into his own coffers strengthens himself.”16

Later in her career, Wells reversed course, beginning to emphasize citizenship over industrial education. Vocational education in some trade could not replace and was insufficient for acquiring civic virtue. Black freedom could not be bought by better skills; it required agitating politically. Directing her ire toward Washington, she wrote that “industrial education will not stand [the black American] in place of political, civil and intellectual liberty, and he objects to being deprived of fundamental rights of American citizenship to the end that one school for industrial training shall flourish.”17

Wealth did not necessarily engender good leadership, nor was good leadership a passive activity where one simply modeled the kind of good economic behavior one wished others to adopt. As she asked rhetorically in “Functions of Leadership” (1885), “tell me what material benefit is a ‘leader’ if he does not, to some extent, devote his time, talent and wealth to the alleviation of the poverty and misery, and elevation of his people.”18 Leaders needed to fight for the common good irrespective of the economic costs and maintain truthfulness in the face of injustice. For Wells, what was needed was more

men and women who are willing to sacrifice time, pleasure and property to a realization of it; who are above bribes and demagoguery; who seek not political preferment nor personal aggrandizement; whose natural courage is strong enough to tell the race plainly yet kindly of its failings and maintain a stand for truth, honor and virtue.19

Wells’s view of political responsibility also was deeply iconoclastic for its time. A rallying cry for Progressives was that without deeds, political change would only be a nascent idea. Few could deny something even deeper: Without words, ideas were impossible. In the cutthroat, highly lucrative market of the newspaper industry in the 1890s, words of “yellow journalism” were tools of incitement and sensation. No scruples existed when propagating the right falsehood—however egregious—to make an extra buck. Suffering was plentiful, easily exploitable, and emotionally resonating. Wells disagreed:

If indeed “the pen is mightier than the sword,” the time has come as never before that the wielders of the pen belonging to the race which is so tortured and outraged, should take serious thought and purposeful action. The blood, tears and groans of hundreds of the murdered cry to you for redress; the lamentations, distress and want, of numberless widows and orphans appeal to you to do the only thing which can be done—and which is the first step toward revolution of every kind—the creation of a healthy public sentiment.20

Responsible journalism meant not preying upon but amplifying and attending to the complex suffering of those who were the most vulnerable—children, who couldn’t freely exercise their rights without parental authority, or those, such as orphans and widows, whose rights were deeply compromised, if ever guaranteed, for example, the New York City tenement slum populations that were the subject of Danish-American Jacob Riis’s widely influential book of photojournalism How the Other Half Lives (1890).

Riis’s photographs helped outrage the public, but his own disdain for and sometimes racist view of the immigrants he photographed raises two important interrelated questions: Might registering the suffering of vulnerable populations keep intact ideologies of racial or class hierarchy? Cannot one overlook the complex nuances of oppression or speak problematically on behalf of those whose voices can’t be heard?21 Wells understood these problems without any formal philosophical training years before they received their most influential articulation by one of the most esteemed American philosophers of her generation, William James.

In an 1899 talk, “On a Certain Blindness in Human Beings,” James recalled how visiting the North Carolina countryside made him appreciate the fact of human finitude, the limitation of fully knowing people’s experiences and motivations. After speaking to a mountaineer in the region, what James initially believed was nothing more than an ugly open field expressive of squalor was revealed to be a manifestation of resilience, “a symbol redolent with moral memories and [that] sang a very pæan of duty, struggle, and success.”22

Technologies meant to improve our understanding of the world—the motion picture, photojournalism, and newspaper circulation—gave rise to the collective myth in the 1890s that everything could be fully known. Knowledge was less in a state of crisis than it was considered an antidote to suffering. Much like James transformed his own intellectual blindness about human plurality into an argument for greater humility about human knowledge, Wells turned the limitations of journalism (the creation of the public sentiment was the “only thing which can be done”) into an argument for activism. Sometimes she put this point more directly to the reader: “You can help disseminate the facts … by bringing them to the knowledge of every one with whom you come in contact, to the end that public sentiment may be revolutionized. Let the facts speak for themselves, with you as a medium.”23

Activism, for Wells, was a condition through which to minimize suffering rather than to speak for those who experienced it. The only thing the activist could do was to mobilize the public sentiments of outrage and shame to address the national disease of injustice—and this was possible because emotions were incredibly powerful. “Public sentiment,” Wells wrote, “is stronger than the law.”24 The best thing the activist could do was to appreciate his or her own epistemological limitations.

Both positions stemmed from Wells’s deeply held commitment to democratic individualism. Moving from passivity to action was both a possibility for all—whites and blacks, leaders and ordinary citizens—and it had to emerge from within rather than be imposed from without. “Do you ask the remedy?” for lynching, she wondered. Her answer: “A public sentiment strong against lawlessness must be aroused. Every individual can contribute to this awakening.”25

THE BRUTAL CONTRADICTIONS OF DEMOCRACY

Few Americans were as concerned as Wells with the fate of democracy, even at a time in U.S. history when the term was being hotly contested. In the late nineteenth century, reformers tried to bring to American shores the social-egalitarian democratic vision implicit in the French Revolution’s declaration of liberty, equality, and fraternity.26 For some, nothing mattered more than regulating the excesses of monopoly capitalism and big business of the Gilded Age, which many believed were responsible for social ills.27

Yet Progressive reformers would be met with vociferous intellectual resistance. For William Graham Sumner, social democracy’s redistribution of wealth encouraged political mediocrity that only led to bad decisions. Reformers, Sumner lamented, ignored the “faults” of poor people, while the person “who raises himself above poverty appears” to them of “no account.”28 Sumner cared little for the plight of African Americans and even less for those lynched in the Deep South. But had he paid attention to Wells he would have learned that the virtues he extolled in capitalism did not simply unleash equal opportunity and prosperity for all but led to excruciating violence for some. A smaller-scale version of those “captains of industry” Sumner championed in “The Absurd Effort to Make the World Over” (1894) for their “power to command, courage and fortitude” were, as Wells described, the very leaders of the bloodthirsty lynch mob.29 “On Wednesday afternoon a meeting of citizens was held,” Wells explained in a speech in Boston, “Lynch Law in All Its Phases” (1893), delivered one year before Sumner’s article was published: “It was not an assemblage of hoodlums or irresponsible fire-eaters, but solid, substantial business men who knew exactly what they were doing and who were far more indignant at the villainous insult to the women of the south than they would have been at any injury done themselves.”30

Less a critique of the economic inequality capitalism produced, Wells’s observation disclosed the instrumental logic at the heart of lynching: that people could simply be manipulated for one’s benefit rather than be considered as possessing inherent, inviolable human value, that is, be seen as ends in themselves. The young Marx believed this phenomenon was actually a chief function of capitalism, which treated workers as objects to be profited from and which made them see one another as exchangeable commodities. As he put it famously: “In estranging from man … his own active functions, his life-activity, estranged labor [under capitalism] estranges the species from man.”31 The black body, for Wells, was rendered into an inanimate object that had little moral status—much like the commodities workers were producing. Wells wrote: “The finding of the dead body of a Negro, suspended between heaven and earth to the limb of a tree, is of so slight importance that neither the civil authorities nor press agencies consider the matter worth investigating.”32 The deliberate, amoral, methodical mutilation of a black body—part by part—without any qualms represented a perversion of hyperrationalism and detachment. Lynching, Wells wrote, “is not the creature of an hour, the sudden outburst of uncontrolled fury, or the unspeakable brutality of an insane mob. It represents the cool, calculating deliberation of intelligent people.”33

The rational violence of lynching, its ordered chaos, rendered dubious Jane Addams’s explanation that lynching represented a moment of unhinged emotion. Addams was wrong, Wells explained, when she said that “human nature gives way under such awful provocation and that the mob, insane for the moment, must be pitied as well as condemned.”34 A tragic view of democracy—in which individuals were seen as vulnerable to passion and lapses of judgment—was the subtext of Addams’s explanation, but Wells saw that the tragic denial of democratic freedom and psychological security to African Americans stemmed from the same logic that denied it to the poor people Addams wished to save. “It is strange,” Wells continued, “that an intelligent, law-abiding, and fair minded people should so persistently shut their eyes to the facts in the discussion of what the civilized world now concedes to be America’s national crime.”35

Few moments in American history saw such an increase in philosophical defenses of unbridled individualism, but the late nineteenth century was also the age of the crowd. Seeing firsthand the spectacular crowds of the late nineteenth century—the lynch mob, newly arrived Irish immigrants living in close quarters, angry laborers, starving children—must have heightened Wells’s appreciation about the way that the abstract idea of “the people” is distinct from the institutions it claims to legitimize and can be seized by whoever speaks on its behalf.36 The crowd, which crystallized the problem of popular rule, frightened one of Wells’s contemporaries, the French sociologist Gustave Le Bon, who argued in his classic study The Crowd (1895) that it captured how individuals deferred their personal responsibility to an unthinking collective, a condition in which reason was entirely absent and impulsiveness reigned supreme. “In the collective mind the intellectual aptitudes of the individuals, and in consequence their individuality,” Le Bon wrote, “are weakened. The heterogeneous is swamped by the homogenous and the unconscious qualities retain the upper hand.”37 But for Wells the problem was the exact opposite: the ability of democratic popular sovereignty to encourage a troubling perception of individual judgment.

Wells asked rhetorically: “Who sits in judgment on the ‘supposed’ character of the lynched.… Who ‘supposes’ the victims of lynch law are bad characters? Those who suppose they are justified in murdering them, and must have some excuse for their crimes.”38 Democracy is usually associated with good judgments: citizens giving reasons for who they elect, how they rule directly, or—in a more legalistic sense—juries and judges giving rationales for their verdicts. However, if we take seriously the notion that all citizens—for better or worse—should have the authority of judgment, regardless of the way it is exercised, then calls to justify citizens’ judgments can be treated with contempt.

The lynchers’ judgment is distorted because one can insist that democracy is as much defined by the authority to make judgments about one’s polity as it is through a respect of the rule of law—the latter being what lynchers reject. But the lynch mob’s insistence on sovereign judgment may follow, even if not logically, from the idea of popular rule and the populist individualist culture in which it emerged.39 Late nineteenth-century critiques of tyrannical elite rule morphed into the widespread view that ordinary citizens had all the right answers, as if this was uncontested.40 Note Wells’s word choice when referring to five black men lynched in 1893: “They were simply lynched by parties of men who had it in their power to kill them, and who chose to avenge some fancied wrong by murder, rather than submit their grievances to court.”41 Lynchers “simply” lynch and “chose” to avenge “some fancied” murder, with no second thoughts about the validity of their judgment to do so. The lynch mob, in Wells’s depiction, provided the dark counterexample to Walker: Sovereign judgment does not aid in racial emancipation but rather justifies racially based murder and the perpetuation of white supremacy.

Central to lynching was also the democratic problem of collective inaction. If lynchers were a minority faction who enacted the will of the silent white majority, or what the sociologist Emile Durkheim called the “collective consciousness,”42 then that tacit consent undermined a liberal, pluralistic society. Wells believed tacit consent could undermine, rather than enable, individual freedom.43 Nowhere was this clearer than in the lynching of Eph. Gizzard. She recalled how “they took him from jail without resistance, dragged him through the streets, plunged knives deep into his body, and rained blows and kicks on him at every step; the militia and police, State and civil authorities looked on unmoved and inert.”44 If the mob’s passivity arises from the seduction of anonymity that Alexis de Tocqueville brilliantly argued characterized democratic societies—where “all the citizens are independent and feeble; they can do hardly anything by themselves, and none of them can oblige his fellow men to lend him their assistance”45—then, for Wells, this desire for anonymity is what accounts for democracy’s unequal dispensation of violence and unimaginable cruelty. For Wells, passive bystanders were as guilty as the murderers:

The men and women in the South who disapprove of lynching and remain silent on the perpetuation of such outrages, are particeps criminis, accomplices, accessories before and after the fact, equally guilty with the actual law-breakers who would not persist if they did not know that neither the law nor the militia would be employed against them.46

Racial tyranny was perpetuated through a radical kind of passivity where neither the state nor citizens interfered in the face of injustice. As Wells put it, when comparing lynching to slavery, “the same tyrant is at work under a new name and guise. The lawlessness which has been here described is like unto that which prevailed under slavery. The very same forces are at work now as then.”47 For this reason, Wells believed a renewed commitment to the rule of law was necessary: “It is a well-established principle of law that every wrong has a remedy. Herein rests our respect for law.… In lynching, opportunity is not given the Negro to defend himself against the unsupported accusations of white men and women.”48

ENVISIONING DEMOCRACY

Wells’s attempts to reframe citizens’ understandings of democracy were deepened by an alternative view of democratic judgment. Before W. E. B. Du Bois’s first scholarly work, The Philadelphia Negro (1899), so richly deployed social-scientific data to account for the complexity and struggles of African American life in Philadelphia, there were Wells’s essays, which signaled the unprecedented potential of social science to become a vehicle for political change.49 Dispassionate empirical thinking, Wells and the early Du Bois believed, obviously had the advantage of rhetorically countering the passion of the lynch mob. The preface to Wells’s A Red Record asserted that the text was “a contribution to truth, an array of facts, the perusal of which it is hoped will stimulate this great American Republic to demand that justice be done though the heavens fall.”50 Making good on this claim, throughout the text, a bold headline for the cause of lynching—“rape,” “murder,” “incendiarism,” “burglary,” “race prejudice,” “quarreling with white men,” “making threats,” “rioting,” “miscegenation,” and “no reasons given,” among many others—would be followed by nothing more than the date when it occurred and the name and location of the person who was lynched.51

Fiery indignation was at the heart of Walker’s call to the black masses, and moral suasion defined Douglass’s early writings to appeal to white people’s sympathy, but a no-nonsense, cerebral appeal to people’s natural reason, which assumed them capable of personally enacting critical interpretation, defined Wells’s approach: “To those who are not willfully blind and unjustly critical, the record of more than a thousand lynchings in ten years is enough to justify any peaceable movement tending to ameliorate the conditions which led to this unprecedented slaughter of human beings.”52 Disinterest could enable one carefully to assess competing perspectives and validity claims to arrive at a reliable understanding.53 So too could it animate civic love toward those who one had never met but who mattered as members of a collective polity.

But Wells did not simply stop with outlining the facts—as Du Bois had in The Philadelphia Negro. This was because lynching was as much a problem of knowledge (of inadequate facts) as it was of spectacle. On the one hand, there was the sensational and complex range of emotional responses that lynching produced—sadness, despair, laughter, shame, or joy—for those who participated in or simply looked at photographs of the rite. On the other hand, there was the spectacularly lifeless, tormented black body that had nothing to say, which perpetuated the cultural image of blacks as abject and voiceless and created space for white Americans to advance their own narratives about black identity. But what kind of optics of seeing could encourage a more democratic future, one in which freedom could be expanded across racial lines?

Wells’s answer entailed transforming William James’s philosophical project of radical empiricism into a political tool. James proposed that all philosophical reasoning—its questions, propositions, and arguments—must be determined by experience. In his famous definition of what he called “radical empiricism,” he described how “the only things that shall be debatable among philosophers shall be things definable in terms drawn from experience.”54 Experience is not only the source of knowledge, but it creates the limits of what kind of knowledge is even possible.55

Wells went further. First, she highlighted the plurality of unseen experiences to disclose black complexity, of which vulnerability was central. In Henry Smith’s lynching in Paris, Texas, for instance, she brought into relief not only the cruelty of the lynch mob but the cruelty of Smith’s mental illness, making vivid that beneath his unimaginable deed of murdering a four-year-old girl was someone who was emotionally unstable—himself in need of compassion rather than punishment. “This man was charged with outraging and murdering a four-year-old white child, covering her body with brush, sleeping beside her through the night, then making his escape.”56

Sometimes psychological vulnerability was a product of structural circumstances. Hamp Biscoe, a “hard working, thrifty” black farmer from Arkansas who lost his property after a dispute over an unpaid debt to a realtor who claimed to sell him the land, became increasingly anxious and agitated. After he and his wife were lynched after he had shot a white constable, John Ford, who attempted to enter his land to arrest him after repeated warnings not to, Wells described Biscoe’s psychological state as follows: “The suit, judgment and subsequent legal proceedings appear to have driven Biscoe almost crazy and brooding over his wrongs he grew to be a confirmed imbecile. He would allow but a few men, white or colored, to come upon his place, as he suspected every stranger to planning to steal his farm.”57 Beneath the act of resisting arrest was a complex person. The threat of serious economic deprivation, if not homelessness, combined with the ensuing sense of despair destroyed Biscoe’s sense of self-worth. The feeling that his perspective was being denied by the courts—“Biscoe denied the service and refused to pay the demand”—reflected Biscoe’s sense of dignity.

Second, rather than view political thought as something emanating from reasonable speculation, urging one to think abstractly about hypothetical people living out hypothetical scenarios, Wells followed Douglass in arguing for embodied experience to drive political thinking. Douglass’s belief was that doing this would pluralize monolithic definitions of freedom, but Wells wanted experience to be the test for the existence of justice. The sad state of the American legal system, epitomized by the U.S. Supreme Court’s embarrassing support of Jim Crow in Plessy, made futile any appeal to equal legal protection supposedly guaranteed by the Fourteenth Amendment. The measure of justice, Wells insisted, needed to be how it affected (or was undermined through) living, breathing, and suffering bodies: “Repeated [physical] attacks on life, liberty and happiness of any citizen or class of citizens,” Wells declared, “are attacks on distinctive American institutions; such attacks imperiling as they do the foundation of government, law and order, merit thoughtful consideration of far-sighted Americans.”58

Third, Wells sought to shift people’s vision away from the brutal immediacy of lynching and toward its larger but unseen cultural implications. Viewing the dangling lifeless black body could have led some to feel outrage or enjoyment. These emotional responses could stifle an examination of what lynching reflected about the human condition. Wells wanted to encourage the opposite, showing how the lynched body was a test case for American democracy. Eph. Gizzard was

dragged through the streets in broad daylight, knives plunged into him at every step, and with every fiendish cruelty a frenzied mob could devise, he was at last swung out on the bridge with hands cut to pieces as he tried to climb up the stanchians. A naked, bloody example of the blood-thirstiness of the nineteenth century civilization of the Athens of the South.59

Wells’s account of the lynching places one in the position to see not what the lynch victim does to deserve punishment but what deservingness means culturally. The frenzied stabbing and puncturing of a human being’s delicate flesh and the dismembering of his hands describes the relative ease with which a fragile body that houses a person could be denigrated in a nation where liberal, democratic self-congratulation about American exceptionalism was widespread. “A large portion of the American people,” she wrote elsewhere, “avow anarchy, condone murder and defy the contempt of civilization.”60 Gizzard’s brutalized body testified to the way the liberal idea of bodily security was violated rather than preserved through warm shelter and nutritious food; how apathy, rather than compassion, was supreme; how unrestraint, rather than temperance, defined American public behavior.

Something similar was at work in Wells’s skillful depiction of a lynch mob’s attempt to capture Robert Charles, who became a fugitive after he refused to be arrested on his front porch for suspicious behavior by New Orleans police:

The mob held the city in its hands and went about holding up street cars and searching them, taking from them colored men upon the public square, through alleys and into houses of anybody who would take them in, breaking into the homes of defenseless colored men and women and beating aged and decrepit men and women to death.61

The narrative highlights the mob’s assault on the following vaunted American ideals: the city as a public, pluralistic space that allows for freedom of mobility; the protection from illegal search and seizure; the notion of private property; the idea of habeas corpus.

After reading Wells, few could deny that lynching was not only a highly stylized performance, a ritualized rite with defined rules and symbols—a culture unto itself within American culture—repeated over and over again, but that the thrill and pleasure this rite induced reflected the link between violence and self-expression (it was a creative act), personal identity (one had a sense of who they were by knowing they were not the person lynched), and membership in a community. This was reflected in the death of Lee Walker, who was lynched in Memphis after two women claimed that he had assaulted them after they refused to give him something to eat: “The crowd hurled expletives at him, swung the body so that it was dashed against the pole, and, so far from the ghastly sight proving trying to the nerves, the crowd looked on with complaisance, if not really pleasure.”62 And in that of Ed Coy in Arkansas: “The men and boys amused themselves for some time sticking knives into Coy’s body and slicing off pieces of flesh. When they had amused themselves sufficiently, they poured coal oil over him and the woman in the case set fire to him.”63 Punctured flesh and shattered bones become a reflection of one’s imagination: The more unique the violence, the greater feeling of identity. Recognition in public—from those who were moved in pleasurable ways—creates a community.

HORROR, DISBELIEF, AND SHAME

Describing lynching through the genre of horror was the way Wells sought to inspire citizens to act to achieve racial justice. Horror, according to the contemporary American philosopher Stanley Cavell, is a perception that relates to the “precariousness of human identity,” that this identity can be “lost or invaded,” that “we may be, or may become, something other than what we are, or take ourselves for; that our origins as human beings need accounting for, and are unaccountable.”64 Horror does not immediately appear to be valuable for expanding the polity democratically. The feeling of precariousness horror encourages seems to counter the thoughtful and reasoned reflection necessary for collective rule, while visceral disgust may or may not lead one to struggle for social justice.

Upton Sinclair never expressed ambivalence about horror’s democratic potential. Groundbreaking less for its narrative style, metaphor, and plot and more for its influence on American politics, Sinclair’s pseudojournalistic novel The Jungle (1906), which portrayed in fiction working-class people working under brutal conditions in the meat industry—where unsanitized factories mixed animal feces and other vectors of disease into food—helped inspire the U.S. Congress to pass both the Meat Inspection Act and the Pure Food and Drug Act. Sinclair juxtaposed the way factory workers were “part of the machine … and every faculty that was not needed for the machine was doomed to be crushed out of existence” with the “thousands of rats [that] would race about” the “meat stored in great piles in rooms.”65 Horror, for Sinclair, became a genre through which to blur a sacred boundary between human and animal.

Less concerned with adopting Sinclair’s attempt to create a parallel between human and animal, Wells was interested in developing what was implied in his novel: the ways that horrifying human identities were constituted through a process over which they had no choice or control. An example of this was captured in her description of the Sam Hose lynching in Atlanta, Georgia—an African American worker who killed his white employer, Alfred Cranford, after a tense dispute about his wages:

First he was made to remove his clothing, and when the flames began to eat into his body it was almost nude. Before the fire was lighted his left ear was severed from his body. Then his right ear was cut away.… The scene that followed is one that never will be forgotten by those who saw it, and while Sam Hose writhed and performed contortions in his agony, many of those present turned away from the sickening sight, and others could hardly look at it. Not a sound but the crackling of the flames broke the stillness of the place, and the situation grew more sickening as it proceeded.… He writhed in agony and his sufferings can be imagined when it is said that several blood vessels burst during the contortions of his body. When he fell from the stake he was kicked back and the flames renewed. Then it was that the flames consumed his body and in a few minutes only a few bones and a small part of the body was all that was left of Sam Hose.

One of the most sickening sights of the day was the eagerness with which the people grabbed after souvenirs, and they almost fought over the ashes of the dead criminal. Large pieces of his flesh were carried away, and persons were seen walking through the streets carrying bones in their hands.

When all the larger bones, together with the flesh, had been carried away by the early comers, others scraped in the ashes, and for a great length of time a crowd was about the place scraping in the ashes. Not even the stake to which the Negro was tied when burned was left, but it was promptly chopped down and carried away as the largest souvenir of the burning.66

Hearing news of the Hose lynching, Du Bois rushed to deliver a well-ordered, legalistic statement about the facts of the case to the white journalist and children’s book author Joel Chandler Harris, to be published in the Atlanta Constitution. A gruesome sight made him stop dead in his tracks. Just up the road, Hose’s knuckles were being displayed in a grocery-store window. Turning back immediately, Du Bois became convinced that the detached social-scientific work that had informed The Philadelphia Negro was unconscionable.67 The Souls of Black Folk (1903), the collection of essays published four years later, expressed Du Bois’s conversion from naïve social scientist to political activist. In that text, critical analysis mixed with experimental prose to create a stream-of-consciousness account of the lived experience of race as a kind of double consciousness: of being both black and American.68

Rather than simply humanize black Americans as did Du Bois, Wells described how black dehumanization was less an a priori truth and more a meticulous white supremacist social construction. Highlighting the intensity and methodical accuracy with which they dismembered Hose’s body piecemeal also reflected the wish to excise black people from humanity. Publicly destroying black bodies communicated white anxiety about black equality. If black inferiority were truly a biological phenomenon that could not be changed (according to social Darwinist theories of scientific racism that were taken seriously, black men were hypersexual, intellectually feeble, lazy, immature, duplicitous, and criminal), then the symbolic act of lynching seemed unnecessary.69 Dehumanization thus had to be achieved. Wells’s language illuminated this clearly when she told how six black men in Memphis “were made the target of murderous shotguns, which fired into the writhing, struggling, dying mass of humanity, until every spark of life was gone.”70 Strategically using the passive voice—black men were “made the target of” as opposed to them “being targeted”—emphasizes the process of how human beings were made lifeless despite their protests. Giving agency to an inanimate instrument of violence—it was the shotgun, not the person that “fired”—blurred the line, if not creating striking parallels, between the lynchers and the guns they used. Lynching, in other words, had brutal effects on lynchers.

The imagined white masculine moral virtue that led to lynching was the same thing that eroded white Americans’ moral sense. What at first was expressed publicly and in racially specific ways could soon come to know no boundaries. “The beast of prey which turns to destroy its own is not considered less,” she wrote in another context, “but more bloodthirsty and ferocious than when it preys on other animals. The taste for blood grows with indulgence, and when other means of satisfying it fail he turns to rend his own household.”71 Violence offers no durable sense of identity, but it entirely infuses one’s personality and social relationships.72 People “forget that a concession of the right to lynch a man for a certain crime,” Wells told readers, “concedes the right to lynch any person for any crime.”73

Identifying this interconnected process of black and white dehumanization was part of Wells’s larger unifying rhetorical objective: the creation of disbelief. The following statement captured this perfectly:

When that poor Afro-American was murdered, the whites excused their refusal of a trial on the ground that they wished to spare the white girl the mortification of having to testify in court.

This cry has had its effect. It has closed the heart, stifled the conscience, warped the judgment and hushed the voice of press and pulpit on the subject of lynch law throughout this “land of liberty.” Men who stand high in the esteem of the public for Christian character, for moral and physical courage, or devotion to the principles of equal and exact justice to all, and for great sagacity, stand as cowards who fear to open their mouths before this great outcry. They do not see that by their tacit encouragement, their silent acquiescence, the black shadow of lawlessness in the form of lynch law is spreading its wings over the whole country.74

Disbelief upends conventional ways of understanding the world. Linking the distorted body of the lynched victim with that of the passive citizen in the above passage—whose “closed” heart and “stifled” conscience parallels the lifeless heart of the dead lynched victim whose conscience no longer exists, whose “warped” judgment parallels the contorted body of the lynched victim, whose silence and gaping mouth parallels the lynched victim’s limp face—Wells forced American readers, who stood by idly without agitating politically while their fellow compatriots were being lynched, to see themselves in jarring ways. If Americans were prepared to ask themselves the questions that such recognition might yield—Is this really what we’ve become? How can we support this?—Wells hoped that they would find a way to change.

This passage, however, also revealed Wells’s thinking about shame. If Douglass in My Bondage and My Freedom was optimistic that white males’ sense of shame at violating their masculine and racial superiority could create a space for black freedom—Covey was ashamed to let any of his friends know about the fight with Douglass, which allowed Douglass to continue plotting his escape—Wells worried that it would do exactly the opposite. The sense of character deficit that shame conjures could be paralyzing, forcing people to withdraw from critical examination rather than engage in it.75

Shame at violating the expectations that arose from the misogynistic view that women were too fragile and too traumatized to speak about the trauma they experienced kept in place, rather than exploded, these misogynistic assumptions.76 “The white people won’t stand for this sort of thing,” she wrote, “and whether they be insulted as individuals or as a race, the response will be prompt and effectual.”77 This extended across racial lines. “Even to the better class of Afro-Americans the crime of rape is so revolting,” Wells wrote, “they have too often taken the white man’s word and given lynch law neither the investigation nor condemnation it deserved.”78 Shame had a chilling effect on democratic deliberation: No one wanted to talk about rape, examine whether it truly occurred, or force the alleged victim to relive her experience because doing this would challenge the expectation of women’s lack of agency and threaten the fantasy of male chivalry. Neither lynching nor the masculine myths upon which it rested could ever fully be examined and rejected.79

THE BONDS OF INTIMACY

Jim Crow segregation is usually recalled for its tactics of political disenfranchisement, its racially based economic inequality, and the public humiliation to which it subjected Southern blacks. But it was also about the private realm, of which the policing of human intimacy was crucial. Lynching may have been predicated upon the white supremacist fantasy that black men wished to rape white women, but the existence of antimiscegenation laws made apparent that the mundane fact of interracial relationships was an egregious transgression of the deeply etched line of racial difference. Many whites took this crime to be more sinful than the so-called unspeakable crime of rape.80

Wells rendered this line of racial difference fictitious by exposing the inescapable interracial intimacy that existed beyond and against the written law. “In numerous instances where colored men have been lynched on the charge of rape,” she wrote, “it was positively known at the time of lynching, and indisputably proven after the victim’s death, that the relationship sustained between the man and woman was voluntary and clandestine, and that in no court of law could even the charge of assault have been successfully maintained.”81 Not only was interracial love voluntary, but Wells described how it was frequently instigated by women. Casting women as conscious agents in interracial encounters reversed the male fantasy of women’s passivity and undermined the racist myth of black men’s uncontrollable hypersexual desire. Wells quoted Mrs. J. C. Underwood of Ohio, who first accused an African American of raping her but eventually confessed that “he made a proposal to me and I readily consented … in fact I could have resisted, and had no desire to resist … I hoped to save my reputation by telling you a deliberate lie.”82

Furthermore, Wells depicted how human intimacy could not be completely regulated by racial segregation because intimacy was fundamental to and pervasive in everyday human interactions. Antimiscegenation laws could never stifle the brief but impossible-to-control everyday act of intimacy like the smile, which also became one reason for lynching:

The truth remains that Afro-American men do not always rape [?] white women without their consent … there are many white women in the South who would marry colored men if such an act would not place them at once beyond the pale of society and within the clutches of the law.… When men lynch the offending Afro American, [they do so] not because he is a despoiler of virtue, but because he succumbs to the smiles of white women.83

Smiling can be an invitation to friendship or an expression of flirtation; it can also sometimes be quite trivial, nothing more than a reflexive gesture of neighborliness into which one doesn’t put much thought.

Here and throughout her writings, Wells transformed desire into something untethered to racial identification. Nowhere was this more apparent than in the example of a white woman, Sarah Clark of Memphis, who “loved a black man and lived openly with him,” and “when she was indicted last spring for miscegenation she swore in court that she was not a white woman.”84 Desire was not simply a threat to standards of piety and self-control championed by some Progressives. Desire was also a creative force, unleashing the self that racial identity imprisoned in new directions and opening it to new experiences, roles, and possibilities. Strict adherence to race dictated the range of pleasures one could partake in, but adherence to pleasure could remake one’s identity, as was clear with Clark’s renouncement of her whiteness. As much as this was a form of privilege unequally enacted—as it would have been impossible for Clark’s black lover—it nonetheless was an embrace of vulnerability.85 Race created boundaries defined by hierarchy, while intimacy made one precarious—Clark’s connection to a community was much easier and less risky than the connection to her lover, who could have left her at any moment or betrayed her in a much more emotionally devastating way. Choosing the riskier of two options—rejecting whiteness and spurning her community—constituted an acceptance of the unknown along with its dangers and beautiful possibilities.86

HOPE AND THE POLITICS OF STRUGGLE

The same year that the founder of the periodical The New Republic, Herbert Croly, would crystallize in The Promise of American Life (1909) the ideal of political hope that drove the Progressive movement, the NAACP (National Association for Colored People) was founded partly as a response to government inaction toward lynching. For the American, Croly wrote, “the better future, which is promised for himself, his children, and for other Americans, is chiefly a matter of confident anticipation.… The better future is understood by him as something which fulfills itself.”87 For the NAACP and Wells, who was also one of the organization’s first signatories (though she did come to believe it to be more moderate and less radical than she had wished), hope instead straddled the line between realistically acknowledging and attending to society’s tragic limitations while dreaming of a brighter future to come. As Wells told her readers at the conclusion of A Red Record:

Think and act on independent lines in this behalf, remembering that after all, it is the white man’s civilization and the white man’s government which are on trial. This crusade will determine whether that civilization can maintain itself by itself, or whether anarchy shall prevail; whether this Nation shall write itself down a success at self government, or in deepest humiliation admit its failure complete; whether the precepts and theories of Christianity are professed and practiced by American white people as Golden Rules of thought and action, or adopted as a system of morals to be preached to, heathen until they attain to the intelligence which needs the system of Lynch Law.88

Wells, unlike Croly, had no reason to believe that progress was a given, especially where race was concerned. But, while under threat from the violent uncivil mobs that she denounced, Wells would continue using the pen and the podium to speak against a national racial problem that many Americans did not see as a serious political issue.89 She spoke to packed halls in England, worked to resuscitate the National Equal Rights League, founded the Negro Fellowship League, and unsuccessfully campaigned for an Illinois state senate seat in 1930. A similar sense of hope informed the NAACP legislative agenda of reform: It successfully persuaded the U.S. House to pass the Dyer Bill in 1922, which would have made lynching a federal crime (before it was filibustered to death in the U.S. Senate), and it was instrumental for drafting the Costigan-Wagner Bill in 1934, which would have held federal trials for law-enforcement officials who failed to act during a lynching but which floundered after the highest-ranking Democrat in office, President Franklin Delano Roosevelt, refused to lend it his support given his fear of alienating Southern Democrats, who were a crucial part of his governing coalition. Yet, Wells’s activism and the activism of the broader antilynching movement to achieve the impossible embodied a sense of hope that understood practical constraints but nonetheless consistently pushed against the boundaries of the dominant enactments of politics, which called for deferring to the logic of what existed rather than aiming toward a future that didn’t yet.

EXTRALEGAL VIOLENCE AND THE AMERICAN POLITY

For Americans today, lynching appears to be a distant part of a racist American past that has been slowly, even if unevenly and incompletely, addressed over the past century. This distance has been marked even further through what has become in contemporary American politics the only tactic of grappling with historical racial injustice: the official state apology. Too radical was the prospect of giving monetary reparations to the descendants of lynching victims. So in 2005 the U.S. Senate took a symbolic route, apologizing for the federal government’s repeated historic failure to enact federal antilynching legislation.

The event was not without its irony. After all, lynching has not been eliminated from American society. The brutal murder of a fourteen-year-old African American boy, Emmett Till, in Money, Mississippi, in 1955 for smiling at a white woman at a grocery store may now be a distant memory for some, but many still remember the not-so-distant murder of Yusef Hawkins, a sixteen-year-old African American who was beaten and shot to death by a mob of white men in 1989, when he entered a white Italian-American neighborhood, Bensonhurst, in Brooklyn, New York—because the mob suspected that he was dating a local white Italian woman. Even fewer can forget what happened a decade later, in 1998, when three unabashed white supremacists in Jasper, Texas, tied a forty-nine-year-old African American man, James Byrd Jr., to the back of their pickup truck and dragged his body across asphalt for three miles. His crime: walking along the side of the road. As much as a symbolic act, lynching also still works as a powerful symbol: In 2006, several nooses were discovered hanging from trees around a public high school in Jena, Louisiana, after a black student, who was part of the 10 percent black student population there, decided to sit beneath a tree that some of his classmates had somehow deemed the exclusive property of the white student population.

It is correct to associate lynching first and foremost with racism, but the deeper problems that it reflects about American democracy still remain. We are still grappling with the issue of vigilante justice when groups like the Minutemen—citizens with no state-sanctioned authority—patrol the U.S.-Mexico border in search of Mexican migrants or when a neighborhood watchman like George Zimmerman kills an unarmed black teenager, Trayvon Martin, in Sanford, Florida, in 2012, for what he perceived as Martin’s suspicious behavior. We have also witnessed the way violence has been used as a public spectacle to police the boundaries of normative ideas about sexuality, like the 1998 violent homophobic killing of a gay Wyoming college student, Matthew Shepard, and to instill fear into populations who do not express these norms, from the Islamophobic attack on a Sikh temple in Oak Creek, Wisconsin, in 2012 by a white supremacist that left six people dead to the more recent Charleston, South Carolina, church shooting, which saw another white supremacist gun down nine African Americans at a historic black church in June 2015.

Without question—compared to the early twentieth century—the American government has taken a much more active role in addressing such violence. In the aftermath of the Civil Rights Act of 1968, many states have put into effect hate-crime laws that—in conjunction with those at the federal level—add harsher penalties for crimes committed with the intention to discriminate against people based on everything from race, gender, sexuality, disability, religion, and ethnicity. Yet one wonders whether such laws are enough when they cannot themselves alter the attitudes toward citizenship.

Wells offers some insights into what shifts might be necessary. Citizens need to acknowledge how instrumental thinking can create apathetic behavior, how popular sovereignty can lead to violence, and how injustice can exist through collective inaction. And they would need to attend to human complexity and vulnerability, all while being cognizant of the political limitations of shame and the power of human intimacy. In Wells’s view, such a practice of citizenship was strenuous, but it was necessary for all those concerned with the fate of U.S. democracy. Silence was not an option, as Wells told readers: “Can you remain silent and inactive when such things are done in our community and country? Is your duty to humanity in the United States less binding? What can you do, reader, to prevent lynching, to thwart anarchy and promote law and order throughout our land?”90