She loved him then, she loved him now

She met him in a dream some way, somehow,

He is hers as she is his, their destiny had already been written

This henna on her hands tells her so,

In her hands his heart is gently rocked to and fro.

—Anonymous

Henna’s Journey

Although henna was predominantly used in ancient times as a medicine, it later emerged as a highly important part of various cultures’ celebrations, rites of passage, and protection rituals.

Each country has a different way of preparing and using dried henna, and there are myriad recipes for mixing the paste and applying it to the skin. The dried and crushed leaves can be mixed with other herbs, oils, and spices to create different hues and permanence. Black tea, coffee, cloves, indigo, lemon juice, eucalyptus, and tea tree oil are some of the familiar ingredients used.

The art form itself also varies from region to region, with each culture having differing depictions of symbols and tracery. Many of the practices overlap to some extent, but each religion or tribe has its own distinct way of applying henna for the resulting designs.

However, a key element in all of the sacred body art is that somewhere within it is a conscious or unconscious magical belief. Most of the designs protect, repel, entice, or include specific symbols to connect with a certain energy or goal—a perfect example of sympathetic magic. The skin becomes a living charm, amulet, or talisman and allows the energy of the person to flow through it, thereby creating a powerful and beautiful current.

And so henna has been used to accompany people throughout the many rites of passage in their lives, bringing colour and vitality into the occasion or functioning as a comforting (or stark) reminder of the path to be followed.

Henna in India

In India, the name of henna for skin decoration is traditionally known as mehndi, and its most common use is for festivals and special occasions such as weddings, births, funerals, and so on. It is a very important part of Indian life and is considered to be very lucky; adornment of brides’ hands and feet is almost mandatory. Mehndi incorporates intricate, lacy, floral, or paisley designs covering the hands, feet, arms, and shins; sometimes the back or chest is also decorated. The designs also incorporate spiritual or religious aspects, although the overall result is often abstract. In Indian culture, women have always been encouraged to pay particular attention to their bodies and beauty. The Kama Sutra gives clear instructions as to how they should make themselves alluring to men—amongst other things, they were taught how to tattoo themselves with henna and to stain their nails and teeth! It also mentions that a woman makes the transition from virgin to seductress when adorned with henna before her wedding.

When an Indian girl has her first menstrual period, the women celebrate her transition from child to woman with her first henna application, and she is then taught the “art of love” in preparation for her future marriage. Mehndi is listed within the Kama Sutra as one of the sixty-four arts for women, and the darker the stain and the more elaborate the design is said to be an indication of how well the young woman has been instructed in the art of love. Basically, if the design took a long time, her erotic lessons would have been more in-depth!

Henna artists in India are traditionally a part of the Nai, or Barber caste, and the practice is passed down through the generations. Many artists are also women who are unable to work outside the home, who offer exquisite handiwork for brides and festivalgoers, of which there are many, for every joyous occasion is usually accompanied by henna applications.

Henna in Africa, the Middle East, and Islam

Henna became part of the Islamic culture in or around the sixth and seventh centuries ad and spread throughout the Middle East along with the religion. As Islam forbids the use of human representation in art or decoration, the use of images bearing human faces or those of animals or birds are disallowed. So most Middle Eastern designs tend to be more abstract and less dense, featuring graceful floral and vine patterns, similar to those found in Arabic art and tile/textile designs. These are much less complex than the mehndi designs used in India. Henna is much used even to this day for the Muslim religious festivals, particularly Eid al-Adha, the Feast of Sacrifice.

Henna was first used in Morocco with the migration of the Berbers to the region, most likely from Yemen. When the Arabs invaded during the eighth century, they added the rich Berber culture to their own. Because Islam forbids the use of tattoos, women learned to use henna as a means of decoration. The designs were employed for ritual use to help protect against the evil eye and also for traditional celebrations such as weddings, births, and funerals. Traditional Berber and Moroccan designs are usually made up of bold geometric shapes, eyes, plants, and flowers, and they are undeniably beautiful in their uniqueness, full of magical symbolism. The number five is symbolic in both the Jewish and Islamic traditions and is often depicted as a hand known as a khamsa (hamsa, hamesh, or chamsa), meaning “five” in Hebrew; it is more commonly recognized as the Hand of Fatima or Hand of Miriam. The numeric symbolism is illustrated by the five digits of the hand, which in turn can remind us of the five pillars of Islam; Heh, the fifth letter of the Hebrew alphabet and part of the holy name of God; and also the five books of the Jewish Torah. This design is seen all over the Middle East on jewelry or wall hangings, or painted on the walls, and it is believed to be a powerful defence against the evil eye (see chapter 4).

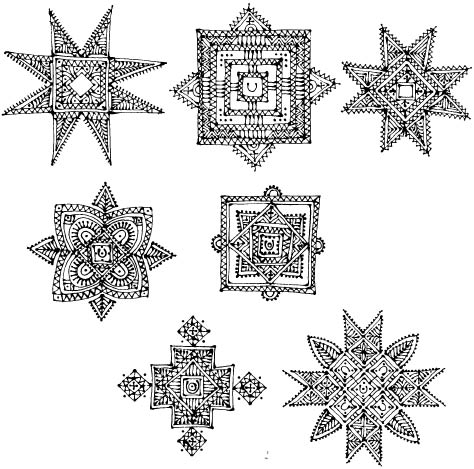

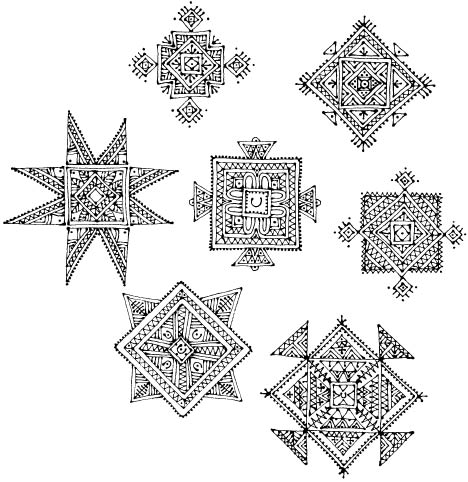

Most of the henna designs were created as charms for fertility and protection of all kinds, made up of triangular, star, or diamond shapes; these angular, geometric motifs were designed to repel negative forces by their sharp contours. One of the most simple yet powerful designs is of an eye within a heart, which is believed to protect your beloved from the covetous looks or advances of others.

© Alex Morgan, www.spellstone.com

Khamsa patterns

© Alex Morgan, www.spellstone.com

Khamsa patterns

Henna in Jewish Cultures

The documented use of henna by Jews is found in writings by the Romans. There is also some reference to the painting of hands with henna as far back as Old Testament times. Sephardic Jews used henna as decoration for their celebrations as far back as 1000 bce. Kurdish Jews used henna in their social and religious celebrations as recently as the twentieth century.

Henna Rituals in History and Beyond

Pregnancy and Childbirth

Pregnancy and childbirth were seen as two very important times when the mother and child needed as much protection and blessings as possible. It was seen as a precarious time, as it was believed in many cultures that evil spirits lurked where there was the promise of pure new life and the spilling of blood. In most of the Middle Eastern, Asian, and North African lands, traditional rituals and celebrations would accompany both the late stages of pregnancy and the process of childbirth. All of them reflect the use of sympathetic magic—using symbols, charms, spells, or talismans that bring about a positive and protective result.

In India, the eighth month of pregnancy is deemed particularly auspicious, and the athawansa ceremony is performed. On the first day of her eighth month, the mother-to-be is ritually bathed using perfumed water, and then she has mehndi applied to her feet and hands, similar to that of her wedding day. She is then richly dressed, sat on a ceremonial seat, and piled high with trinkets, sweets, and a coconut, which is a traditional part of the ritual, called “the filling of the lap.” The whole ceremony is designed to help the woman feel protected and firmly part of the community.

In Morocco and areas where the Berber people (or Amazigh) lived, before the actual birth, women would be decorated as if they were once again a bride, with henna, kohl, and a lip stain made from crushed walnut root. This was predominantly for protection, but as there was always a risk of death while giving birth, she was also prepared to be received as a bride in paradise. The area around the birthing room would also be ritually prepared by the midwife and attending women. A circle of protection would be drawn around the mother-to-be with a sword, and amulets, talismans, and incense would be placed around the room. The laboring woman would be hennaed with protective symbols to repel djinn, or malicious spirits. The Berber woman would be covered while giving birth so that evil could not see her and attempt to harm her or the baby. In India, after the birth, the woman is hennaed immediately on her finger- and toenails; this ceremony is called jalva pujani and is a ritual to purge the mother of anything negative or impure left over from the delivery of the baby. This is considered a dangerous time for both mother and child, as they need to be protected from malicious spirits and recover from the birthing process.

After the birth, it was common for the mother and child to be kept secluded from the world, surrounded only by her female relatives and the midwife. Seven to ten days later, depending on the culture, a naming ceremony would be held, and the child would be hennaed. In India, the baby would be decorated with solar symbols and held up to the sky to ask for the blessings of the life-giving, nurturing, and protective sun gods. It was symbolic of the child’s appearance into the world and of the mother’s new role and integration back into the life of the village community. Even after the seventh- or tenth-day celebration, the festivities continued as long as the family could afford them; female relatives would help with the running of the household while the new mother continued to rest and spend time with her baby, and this often involved more lengthy sessions of henna application, which required her to be still for several hours. She was also dismissed from household chores to allow the henna to retain its stain for as long as possible; again, this ensured adequate rest and relaxation for the mother for up to forty days after the birth. This time of transition was not only for ritual and traditional purposes but also to give the woman a chance to recuperate fully both physically and mentally, thus reducing the incidence of postpartum illness or depression.

In Morocco, multiple births were classed as particularly auspicious, and the mother was deemed to be incredibly blessed. When the baby was born, the umbilicus would be cut, the end dabbed with henna and ritually disposed of by the midwife. All these protective rituals were comforting to the mother, for she knew that she had been surrounded and protected by people she could trust and that they had done all they could to make sure the birth was as safe as possible. The newborn baby would also be protected from the evil eye by the application of henna, either by dabbing it on their face and hands or via a henna rub consisting of henna mixed with oil or butter that was then massaged all over the baby. This was often applied for the first seven days in place of washing. However, recently it has been discovered that applying henna to infants can be dangerous, as it may expose the child to a rare but possibly fatal blood disorder.

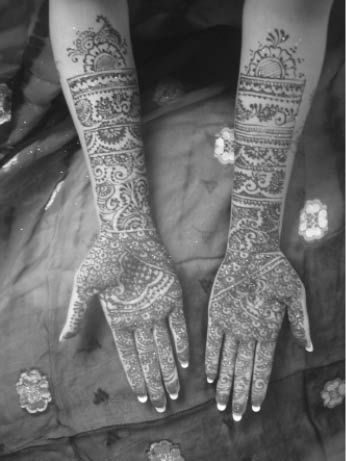

© Farah Khan

Modern mehndi

Circumcision

Boys in the Berber families were not circumcised at birth but rather at the age of four during a family celebration. It was an important and costly affair, and the family would save up for some time to prepare for the circumcision party; there was a sacrificial sheep and a fine suit of clothes for the boy to buy. All the relatives would be invited, fed, and given a gift, and if an eminent family was holding the party, the entire village would be in attendance. The day before the ritual, the women of the family would gather to watch the barber shave the boy’s head. He would leave little tufts of hair, which the women would pay the boy to cut off, all the time trilling and ululating as each piece was neatly removed. Afterwards, they would henna the boy’s hands just the same as if he were a bride. The following morning, his family would take him to the “wedding spring,” called the Tamusi, which is where brides would also be taken prior to their wedding. Here, the boy would be bathed like a bride-to-be before being taken back home for his circumcision. He would appear hennaed and painted, dressed beautifully, and maybe even laid out on a bed like a bride, awaiting his ceremony, whereby he would be admonished to be brave and not to cry during the circumcision. He would be held still while the barber or other experienced authority performed the operation with a sharp knife. The women trill as the skin is removed and the wound covered with henna and a clean bandage. The feast would then commence, followed by much celebration.

Weddings

Henna has long played a part in the beautiful celebrations of marriage held in the Middle East, India, and Africa. In India, weddings are elaborate affairs considered to be one of the most sacred rituals; the celebrations often go on for days before and after the ceremony, with henna playing a huge part. The Hindu pre-wedding ritual of the mehndi raat is one of the most important and involves a fun evening of eating, dancing, and of course henna, attended mostly by friends and relatives of the bride. The actual ritual varies from region to region and is dependent on the financial status of the bride’s family, but on the whole it is a vibrant gathering to bless and celebrate the forthcoming marriage.

The mehndi party is usually held a few days before or on the eve of the actual wedding at the bride’s home or other venue. If no relative is proficient in henna art, a professional mehndi artist is hired to apply the designs to the bride’s hands and feet and perhaps smaller ones on the guests. In some areas, it is deemed auspicious for the mother or the sister-in-law of the bride to apply the first motif. The design is believed to ritualistically transform the bride-to-be from her state of virginity to that of a loving wife for her husband. Popular designs are flowers, fruits, paisley, peacocks, vines, and shells; a common practice is one of hiding the bridegroom’s name somewhere in the pattern, which he then must be clever enough to find! Sometimes the mehndi party is held at the traditional sangeet (a big pre-wedding party for bride, groom, or both), which involves lots of lighthearted banter, singing, and dancing. Before henna was introduced to India, brides would use turmeric, which produced a yellow stain. The spice would be daubed on arms, legs, and head, and then rolled all over her to give a golden glow.

After the mehndi ritual, it is customary that the bride-to-be does not leave her house until it is time for the wedding. During that time, her henna design is observed to see how dark the stain has become; according to tradition, the deeper the colour, the more her husband and in-laws will love her. The length of time the design lasts is also an auspicious sign and is regarded as a good omen that her marriage will be strong.

Weddings in Morocco are similar to those in India; the ceremonies start prior to the actual wedding and include much partying and hennaing. Men are included, and it is the perfect time for a mixture of tradition and serious celebration. The groom’s party starts with his mother presenting him with a gift of henna, an egg, and some water. The egg is broken into the henna paste, and his hands are covered while four candles are lit and placed in the bowl, which is then balanced precariously on the head of his male friends as they dance around the room until is eventually falls and smashes on the floor. Meanwhile, over at the bride’s house, she is dressed in a beautiful ensemble and sits in a throne, where she will spend the evening being pampered and hennaed. Her guests will entertain her by dancing, singing, and offering blessings while the traditional protective patterns of diamonds, triangles, and crosses are applied to her skin.

In the United Arab Emirates, weddings are often very elaborate and costly, with much preparation going towards the ceremony and the preceding rituals. It is not uncommon for the bride to spend forty days in seclusion before the wedding; during this time, she will be showered with gifts from her husband-to-be, including perfume and expensive silks and jewels. The week before the actual wedding ceremony, traditional parties are held with much dancing, singing, music, and henna. The bride’s mehndi will be applied during her laylat al-henna (“night of the henna”), where she is also pampered and massaged with oils and perfume. Mehndi is applied to her feet and hands, and her hair is ritually washed. She is accompanied by her female friends and relatives, who sing, dance, and prepare delicious food to feast upon.

© Sarah Ali Khan, HennaPro

Modern Arabic henna

The Turkish Night of the Henna is once again similar to others with a party, music, and dancing. The bride would leave her guests, and henna would be brought to her on a tray with candles placed in the paste. Her future mother-in-law would thickly henna her right hand, then the left, and then press a gold coin into the paste. The other guests would then do the same. The bride’s hands would be wrapped with the coins firmly in the henna and silk bags slipped over the wrappings. Her feet would then be hennaed in the same way, after which all the guests would join her once more for much raucous dancing and singing.

Often we only associate henna with the Indian or Middle Eastern countries mentioned previously, but its use is equally popular amongst Jewish people. The initial Jewish festivities in anticipation of a wedding begin with a betrothal party. The marriage would have been arranged by the families of the prospective bride and groom, and once the agreement is successful, they would arrange for a qadoshe, or betrothal. The day before the celebration, the family of the groom prepares a feast and delivers it to the girl’s house. The following day, the groom is led in a procession to her home, and she is brought to him and unveiled so that he and all the guests can see that he is being given the right girl. He then kisses her hand, gives her a betrothal ring, and then smashes a wine glass on the floor to seal the deal. He then leaves to celebrate with his friends while the bride’s hair, feet, and hands are hennaed and her friends dance and sing.

In addition to the qadoshe, there would also be the Night of the Henna (lel hanna) and, intriguingly, the False Night of the Henna. Both of these celebrations precede the wedding and involve much henna, food, and dancing.

The False Night of the Henna was actually a diversionary tactic to fool evil spirits into thinking that it was the real Night of the Henna. Because people believed that demons would come to a wedding and bring misfortune, infertility, and disaster to the marriage, it would be held on the Thursday before the wedding, and the real Night of the Henna would be held at the close of the Sabbath.

The real Night of the Henna was a fabulous affair, and although it varied from family to family, the essence was the same: celebrating and hennaing well into the night. The bride and groom would have separate parties (similar to our Western traditions of stag and hen nights) and then often meet up for an extended feast involving both families’ friends and relatives. First thing in the morning, women would bring henna to the groom’s house and mix it in large bowls and leave it to stand until the evening. When it was time for the parties to begin, the mixed henna would be carried by several of the groom’s relatives over to the bride’s house in a ceremonial procession. Musicians would follow them, and the people would sing, “The henna is coming, the henna is coming!” while children attempted to grab the bowls from the carriers. Once the henna arrived, the evening would start by the hennaing of a bridal decoy, a young girl who would fool the evil eye into thinking she was the bride. Instead of focusing their malevolence on the bride, the djinn (or spirits) would mistakenly attack the girl, who would naturally be protected by the henna and could lure them away from the wedding party. The child would sit on the bride’s lap all the while the bride was being hennaed; first, her hair was hennaed to give it a lustrous, glossy colour and shine, and then her right hand and left foot, and then vice versa, each pattern wrapped to protect it. A bowl of the henna would then be taken to the groom’s house while the rest of the bride’s guests and relatives would feast and dance and receive their own henna.

The groom’s Night of the Henna would be similar to his betrothed’s. A young boy would act as decoy for the evil eye and would sit on the groom’s lap while he was hennaed in the same way as the bride, except his side and forelocks were hennaed. Once the hand and feet designs were dried, they were wrapped in linen. Later that night, the groom’s party would make a procession to the bride’s house, where the celebrations and feasting would continue. Eventually the bride and groom would sleep, still with their henna wrappings on, while their families and friends stayed up to keep them protected until their wedding day.

Within the small Jewish Yemeni culture, the prenuptial ceremony is called hinne and is similar to other Sephardic Jewish henna rituals that represent the passage of transition for the bride-to-be from daughter to wife. About a week before the wedding, a huge party is thrown for the bride and her female friends and relatives that involves three processions, all involving a change of dress for the bride. Her clothes are amazingly elaborate and include layers of heavy jewelry that in total can weigh around ten kilograms (twenty-two pounds) and is symbolic of the burden that the bride takes on when she gets married. A headdress completes the ensemble, complete with flowers and herbs to repel the evil eye, and the young girl then begins the zaffeh procession. Her relatives and friends carry baskets of flowers and candles to light her way, and a mournful hinne song is sung about the painful separation of the bride from her family and childhood home. Then the procession breaks into spontaneous dancing, after which another costume change and dance takes place, and then the final procession. After one more change of clothes, the bride then processes to the stage for her henna ritual accompanied by her mother, who carries a basket containing dry henna. Her grandmother then adds water to make a paste, and all her family come and dab their finger into the henna, pressing it into the palm of the young bride and offering her a blessing—“May your life be filled with Torah! Good health, happiness, and love!” The evening then commences with more dancing and singing.

A fascinating article on the Jewish henna ceremony is found on the website jewishtreats.org, including the following excerpt:

According to tradition, the henna ceremony is a way of preparing the bride for her departure from her family, and the henna, pronounced in Hebrew chenah, represents the three mitzvot specifically connected to women: Challah (separating the challah), Nida (family purity) and Hadlakat Nayrot (lighting Shabbat candles).

Henna, the plant, is mentioned several times in the Bible. In particular, Rashi (Rabbi Shlomo ben Yitzchak, France, eleventh century) commented that clusters of henna flowers are a metaphor for forgiveness and absolution, showing that God forgave those who tested Him in the wilderness. So too the bride and groom are given a clean slate with which to begin their lives together.

Death and Funerals

In some regions of Kurdistan, the death of a young man or woman would often prompt the use of henna for adorning the body. If they were unmarried, they would be dressed and decorated as if for their wedding, which would afford them joy in the afterlife. Songs would be sung, and if the young person had been engaged, their bride- or groom-to-be would come, and wedding rings would be symbolically exchanged. Henna would not be worn by the female relatives for a year after the death of a young man as they observed an official mourning period.

There are, however, some slightly darker uses for mehndi, one of which is for the decoration of widows who wish to partake in the ancient tradition of sati (suttee), whereby they voluntarily—or, in some cases, are forced to—burn themselves on their husband’s funeral pyre. Often the same practice would occur if the women lost their men in battle; they would join them rather than become widows. Sati means “virtuous woman,” and historically those who took part in the ritual would be revered as goddesses and believed to ascend directly to heaven. Rajput women would traditionally leave henna handprints on the walls of their house before immolation and often dressed and decorated themselves as they had been on their wedding day. This arcane ritual has been officially banned in India since 1829, but there have been cases as recently as 2008.

War

Henna has long been associated with war. The earliest reference was to the Urgaritic fertility goddess Anath, the virgin warrior who used to henna her hands in celebration of the harvest and the victory over her enemies. There are several accounts of men being hennaed before going into battle—East Indian warriors, Kashmiri martyrs, and Iranian generals all used henna to some degree. The warriors would dip their hands in henna to remind them of their wives and loved ones at home; the Kashmiri men would be sent off to their deaths with hands hennaed by their mothers to fight the holy war. It is possible that the ancient Roman legionnaires used henna to paint their faces in an attempt to terrify their enemies, whereas the Teutonic tribes would dye their hair a flaming red using a mixture of animal fat, ashes, and henna. Catherine Cartwright-Jones mentions the use of henna by the Afghan fighters in the nineteenth century who “earned” their right to henna their fingernails when they had killed enough enemies; their leader described the practice to a traveler of the time as being similar to when “the falcon dips its talons in the blood of its prey.”[1]

It was not just the soldiers that were hennaed in times of war. Often their horses received some henna, with their manes, tails, hooves, legs, and flanks dyed and decorated with striking designs.

Festivals

Karwa Chauth

This traditionally important Indian festival is designed for married women to dedicate the entire day in honor of their husbands and to wish them long life and prosperity. It is a time of fasting to show their devotion, which is then rewarded with fine gifts from both the husband and his family. The rituals begin the day prior to the festival with the mother-in-law giving the wife sargi, which can consist of sweets, clothes, and henna. The application of the henna is an integral part of the festival, not only for good luck but, similar to the wedding mehndi, for the belief that the darker the stain, the more the woman is loved and cherished by her husband.

Ramadan and Eid al-Fitr

Ramadan is the Islamic month of fasting and abstaining from sexual and social pleasures (e.g., smoking) during the period of sunrise to sunset. During Ramadan, Muslims concentrate heavily on their spiritual life, and prayer, charity, and atonement is vitally important, which spans from the first sighting of the crescent moon until the following crescent moon. It is similar to the Christian tradition of Lent, which involves fasting for the weeks before Easter. The Muslim women traditionally forego the use of cosmetics and other external beauty aids, and so when the end of Ramadan is in sight, they begin to prepare their return to their usual routines with the appreciation of a month’s deprivation! The month of fasting ends with Eid al-Fitr (the festival to break the fast), a celebration in comparative importance to the Western Christmas or New Year. This festival lasts for three days. Eid is celebrated to thank Allah for past and future blessings received and is a time when everyone gets dressed up, enjoys festive food, and rejoices.

The women use henna to decorate and beautify themselves, and it is often a time to schedule weddings; almost everyone would have a little bit of henna—maybe just a simple design or a finger dipped in the paste. Some people would even henna their animal’s tails, paws, or ears—dogs, horses, donkeys, and goats would be adorned, much to the delight of the children.

Eid al-Adha

The Festival of Sacrifice is celebrated by Muslims to commemorate Ibrahim’s willingness to sacrifice his son Ismael as an act of obedience to Allah; God then provided a ram in place of Ismael. The festival is celebrated at the end of the yearly pilgrimage, or hajj, and used to coincide with the new growth of the henna plant in spring. Eid al-Adha traditionally involves dressing in the finest clothing and choosing a suitable domestic animal to sacrifice so that meat may be provided to all in the community. If situations do not allow for a sacrificial feast, money may be donated to ensure that food can be bought and distributed. In Islamic countries, the sacrificial animal was hennaed by the women as if it were a bride. Its hooves, tail, and head would be annointed with henna, and sometimes even a mouthful of paste was offered before the animal’s throat was slit. For Eid al-Adha, everyone got hennaed; men, women, children, animals, and even the houses are given a decorative daub before the festivities begin in earnest.

Purim

Purim is a holiday celebrated by Jews to mark the rescue of the Jewish people by Queen Esther, the wife of a Persian king, from a plot to kill them. Until the early twentieth century, Kurdish girls would be ritually bathed, hennaed, and dressed to try and emulate Esther’s beautification before she was presented to the king. Now, Purim is celebrated with colourful plays, readings from the Book of Esther, and joyous feasting, with sweets and gifts given to children and charity.

Henna for Animals

In Lebanon, springtime festivals were a traditional occurrence held in the six weeks before Eastern Orthodox Easter. They were held on successive Thursdays and attended by Christians, Jews, and Muslims, and during two of the festivals it was the animals that received decoration with henna. During the “Thursday of all the animals,” domestic and farmed livestock would effectively have a day off from work and be brought to the festival to mate and “go forth and multiply”—the owners would henna the animals’ foreheads as a blessing and to celebrate life. The last Thursday before Easter saw the gathering of several thousand people at the Shrine of Wali Zaur to receive blessings of fertility, health, and good fortune. Horses and donkeys were decorated with the blue “horse beads” of protection and bright garlands; the beautiful Arabian horses would have their tails dyed with henna, creating a swathe of vibrant red and orange.

A hennaed horse

Henna and the Djinn

Protection and Attraction

Throughout the Middle Eastern countries, the concept of the djinn has played a powerful part in their mythology, religious, and social practice, and a very common use for henna was to either placate or repel djinn.

Predating Islam, djinn were believed to be a race of entities that were part human, part fire—similar to the concept of elementals in the Western tradition. Just as God created man from clay, rendering him half man, half earth, the djinn were created before man from smokeless (or purest) fire. They are believed to be male or female, with the capacity to breed and also shapeshift. They are directly under God’s will and live in a parallel existence to humans, enjoying a social, sexual, and spiritual life, but will still be called to Judgment. In Morocco, the djinn are classified elementally, being linked to earth, air, fire, or water, and often represented by flowers or colours; in some traditions, they are attributed to the number seven and the days of the week.

Like our concept of ghosts, most djinn are predominantly invisible, but they do have a direct relationship with humankind whereby they can be manipulated or coerced into doing the will of the human, often submitting to their invocations and bribes. They can equally be benevolent or malevolent, depending on their inclination—bringing chaos and pestilence or good fortune and health in equal measure. Benevolent and helpful djinn are attracted to all things beautiful and fragrant, and in particular they like henna; when pleased, they happily bestow favors and blessings. Malevolent djinn are renowned to live wherever disease, bodily fluids, blood, or excrement are prevalent, often near rubbish heaps or cemeteries. Pregnant or menstruating women are believed to be particularly at risk from their influence, as are newborn babies. Jealous of the ability of women to get pregnant, give birth, and nurse their infants, the djinn often became incensed and consequently are a threat to both mother and baby. It is believed djinn can enter a woman via her menstrual blood, causing the kind of outbursts of anger, pain, and misery that we now call PMS.

There are a few djinn who are well known in Moroccan legend. Aisha Kandisha, a water djinn, is a particularly voracious spirit who would entrance both men and women, causing them to become so intoxicated by her that they were often driven to the brink of madness. Even today, it is not uncommon for people to be exorcised for possession by djinn, and there have always been special rituals involving the use of henna to rid the possessed of the evil influence. Women were perceived as the best intermediary between humans and djinn, and went through enormous preparation to protect themselves while they undertook the exorcism; they would ritually bathe, dress, and be hennaed in preparation.

If a woman was suffering from mental or physical imbalance or infertility, or was generally unwell, she could ask a medium to intervene or she could take part in a banishing ceremony to remove any malevolent influence. One of these rituals is known as zar and is still practiced in many Middle Eastern countries, either to banish negative spirits or influences or to allow communion with the gods or benevolent spirits. Believed to have originated in Ethiopia and brought to Egypt, the zar is a trancelike experience involving dance and a simple hypnotic music beat. Normally it is only practiced by women; modernly, it is seen as ridiculous by most men and is positively frowned upon by Islam. However, it is an important way for women to gather together and let off steam from their lives in a predominantly patriarchal society.

Similar ceremonies take place in Morocco, often in the form of henna parties, where there is much trance dancing and hennaing to dispel or placate malevolent djinn or, alternatively, to invite benevolent ones to gather. Parties might be held prior to Ramadan—the application of henna would help protect them while they fasted, when they were believed to be more vulnerable to the attention of evil djinn—or simply as a gathering to protect a mother-to-be or new mother and baby.

It is well known that good djinn are attracted to henna, and there is even a henna djinn called Malika, who apparently particularly favors star and floral patterns and loves music, flowers, and the colours blue, mauve, and yellow. She is reputed to bring great joy, love, and happiness into your life, which is certainly a very good reason to invite the henna djinn into your house!

© Sarah Ali Khan, HennaPro

A floral henna design

Children are often affected by the tricks and perils of djinn, and many mothers have used simple henna magic to keep the djinn from their doors. If a child was scared of something unseen or became very sick, it was assumed djinn were to blame; in Palestine, a mixture of salt, barley, sugar, and henna would be used to bribe the djinn to cease its devilry. The mix would be made into little pouches, and for three consecutive nights, one would be put under the child’s pillow, named for the child, the disease, and the cause of the illness, respectively. The pouches would then be thrown one by one down a well (a place where djinn often dwell), and a short petition to the spirit would be recited to ask that good health be returned to the child. Another method would be to scatter the mix in the child’s room and ask the djinn to take the barley to feed their animal, the sugar to treat their children, and the henna to decorate with, and in return the spirit should leave the child and household alone.

Another prudent exercise if you were visiting a house in Morocco and carrying henna was to leave a small amount for the household djinn—throwing a pinch in the fire or on the floor was usually sufficient to appease the spirits. To leave without making an offering was believed to be disrespectful and dangerous, and could lead to the djinn endangering or even killing a member of the household—or, if the guest had not told their host that they had henna, the djinn would attack the guest instead!

Modernly, the djinn and their antics are generally thought of as the equivalent of our fairy tales, but secretly many people still continue with offerings and prayers, just as Westerners still adhere to old superstitions such as touching wood or avoiding going under ladders.

Purification

A Trip to the Hammam

The hammam (Turkish or public baths) was the place where women could gather socially to bathe, be massaged, and apply henna to each other. It was a segregated experience and a peaceful respite from the world of men; children of both sexes were permitted to be with the women, but that was forbidden to the boys once they reached a certain age. A day at the hammam was a special event for the majority of women, and as they were obliged to attend due to religious cleanliness reasons, their menfolk had to let them go. Wealthier women were usually attended by their serving maids, who would carry the items needed for the ritual bathing, hair removal, and hennaing, which included a large bowl filled with towels, premixed henna, sugar mix or caustic lime for depilation, combs, food, drink, and the high wooden shoes called pattens that the ladies wore in the baths to avoid the puddles and other debris. Many of these items would have been given to the women by their husbands as part of their wedding gifts; the richer the men, the more beautiful and highly crafted the combs, shoes, or towels would be. The women often hennaed their hair while in the warm, steamy atmosphere of the hammam, relaxing on mattresses and pillows while the dye worked its magic.

One of the main reasons for visiting the hammam was the postmenstrual cleansing ceremony known as ghusl, which was to purify the body and spirit after the passing of blood. To assist in the purification process, the woman would remove all body hair including that of the pubic region, and there are old illustrations depicting women sugaring or applying henna to each other’s vulvas, something which often led to discreet attachments between the ladies, as homoerotic activity was not uncommon in the hammam. Depilation, as prescribed by the Prophet Muhammad, involved using a sugar mix or a caustic paste, and henna was then applied to soothe and cool the skin, especially around the tender genital area. This process often left the skin with an altered pH balance and made it very receptive to staining.

The hammam was considered to be a dangerous place to be unprotected, as djinn were attracted to water and, of course, women of reproductive age. Often the resident bath attendant would shout or clap to disperse any djinn that might be lurking in the steam; it was often believed that the djinn would enjoy the hammam at night when the other guests had departed. The use of henna was a formidable repellent for any malevolent djinn, whereas it would attract the kindly spirits, for they were partial to the beauty of the fragrant atmosphere and the beauty of the henna. The patterns applied to their bodies changed from region to region, but the premise was the same: purification and protection from infiltration by bad djinn, and the exhibition of the womens’ state of purity and strength.

Ritual Ablutions

The staining of the nails was also used in Muslim cultures from around the fifth century ad. The Prophet Muhammad was said to have encouraged the use of henna on nails, saying that if one is a woman, one must “make a difference to your nails.”

Muslim women are discouraged from using nail polish or anything that does not allow water to reach the nail bed, as it interferes with their use of ritual washing, known as wudu, which is an important part of their daily worship. So instead they often use henna, as it does not create a barrier for correct purification. This is also something that applies to Orthodox Jewish women, who also observe strict cleansing rituals.

© Sarah Ali Khan, HennaPro

Fingers stained with henna

[1] From http://www.hennapage.com/henna/encyclopedia/war/talons.html.