19

Fungi

There is some evidence that the organisms classified as fungi arose from protists along several different evolutionary lines. In fact, depending on the classification, fungi are sometimes placed within the kingdom Protista, within the kingdom Plantae, or in their own kingdom, Fungi.

Fungi are eukaryotic organisms; most exist in multicellular form, although some go through an amoeba-like stage, and others, such as yeast, exist in a unicellular form. Unlike the photosynthetic algae and plants, fungi do not photosynthesize but absorb food through their cell walls and plasma membranes.

The slime molds are different from most other fungi in that they are mobile during part of their life history. Some slime molds exist as a plasmodium, which is a multinuclear (coenocytic) mass of cytoplasm lacking cell walls. The plasmodium moves about and feeds in an amoeboid manner. The amoeboid mass is a slime mold's diploid phase.

Other slime molds have separate feeding amoebas that occasionally congregate into a pseudoplasmodium that then sprouts asexual fruiting bodies. Because they pass through an amoeba-like stage, slime molds are classified as protists by some taxonomists. Slime molds are usually found growing on such decaying organic matter as rotting logs, leaf litter, or damp soil, where these viscous, glistening masses of slime are usually white or creamy in appearance, though some are yellow or red.

During its vegetative phase, the slime mold plasmodium moves about slowly, phagocytically feeding on organic material. Under certain conditions, the plasmodium stops moving and grows fruiting bodies, from which spores are released that upon germination produce flagellated gametes. The gametes fuse, forming zygotes that lose their flagella and become amoeboid. The diploid nucleus continually undergoes mitotic divisions without any cytokinesis, and the organism develops into a multinuclear plasmodium that usually reaches a total length of 5–8 cm (2–3.15 in.).

Most fungi secrete digestive enzymes that hydrolyze nearby organic matter into minerals and compounds that can then be absorbed. Chemicals that don't get absorbed, as well as the fungal waste products, enrich the surrounding area and become available to plants and other nearby organisms.

Fungi obtain their nutrition in any of three ways, or in any combination of these three ways: as saprophytes, living on dead organic matter; as parasites, attacking living plants or animals; and in mycorrhizal associations, in which they have a symbiotic relationship with plants, usually tree or shrubs.

Fungal spores are tiny haploid cells that float through the air, dispersing the fungi to new habitats. They are relatively resistant to high and low temperatures as well as to desiccation, and can survive long periods in an unsuitable habitat. When conditions become right, however, the spores germinate and grow. They absorb food through long, thread-like hyphae. The mass of branching hyphae creates the body of the fungus, called the mycelium. Mycelia grow, spreading throughout their food source. Some hyphae are coenocytic, having many nuclei within the cytoplasm. Others are divided by septa into compartments containing one or more nuclei. The rigid cell walls of the hyphae and fruiting bodies are composed of cellulose, or other polysaccharides, although some are composed of chitin.

The mycelium constitutes the largest part of the fungal body, yet few people ever see mycelia because they are usually hidden within the source of food they are eating. Sometimes, however, they can be seen on the forest floor spreading over moist logs and dead leaves. When mycelia break into fragments, fungi can reproduce vegetatively. Each fragment may grow into a new individual fungus. Other methods of fungal reproduction involve the production of spores, which can be formed asexually or sexually. The spores are usually produced on structures that extend above the food source, where they can be blown away and travel to new environments. Slime molds send up spore-bearing fruiting bodies. The mycelia of mildew send up aerial hyphae that form spores. The fruiting bodies that most people are familiar with, those associated with such fungi as mushrooms, are huge compared to the tiny fruiting bodies that cover moldy bread and cheese.

Most fungi are either parasitic or symbiotic. Parasitism occurs when one individual benefits while the other is harmed, and symbiosis is a mutually beneficial relationship between two individuals. By far, the majority of fungal species are terrestrial and reproduce both sexually and asexually. Many have mycelia that grow in a close, intimate manner with plant roots. In such a relationship, the plant benefits by receiving nitrogen and phosphorus, while the fungus benefits by receiving nutritious carbohydrates. The remainder of this chapter discusses some of the major groups of fungi.

OOMYCOTA: WATER MOLDS

Oomycota, which means egg fungi, is a phylum in the Fungi kingdom that includes the water molds, downy mildews, and their relatives. The powdery mildew found growing on Concord grapes is also a member of this group. There are more than 500 species of these filamentous molds that absorb their food from surrounding water or soil. Oocymota also includes molds that grow on dead animals under water.

ZYGOMYCOTA

Zygomycota represents a group of mostly terrestrial fungi that, like the Oomycota, have coenocytic hyphae. They also have chitinous cell walls. Although there are over 1,000 species in this group, few people recognize any of them because they live in soils and in decaying plants and animals. Zygomycotes form gametes that meet and form a zygote.

ASCOMYCOTA: SAC FUNGI

The Ascomycota, or sac fungi, form another group of fungi that is widespread, although just a few species are familiar. Among this group's 30,000 or so species are the yeasts, certain bread molds, and the fungi that produce penicillin, as well as the species involved in making Roquefort and Camembert cheeses.

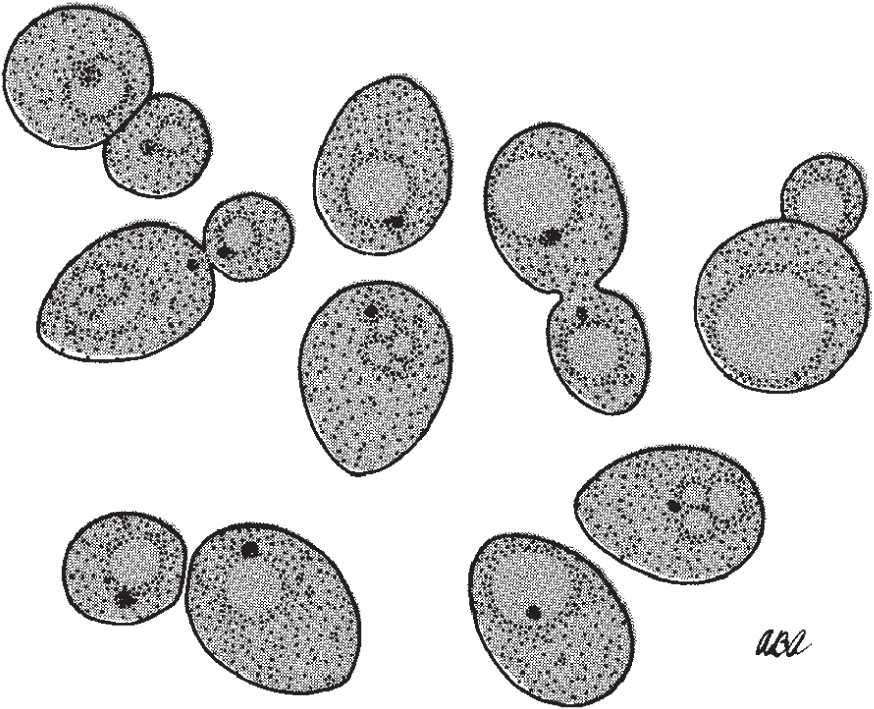

The yeasts are unicellular, but the Ascomycetes also include many multicellular types that form hyphae with perforated septa, allowing the cytoplasm and organelles such as ribosomes, mitochondria, and nuclei to flow from one cell to another (see Figure 19.1).

Asexual reproduction is common among the Ascomycetes. It occurs whenever the projections known as conidia form and the asexual conidiospores pinch off. The sexual part of the life cycle involves two hyphae growing together so that the two nuclei become housed within the same cell. When these cells, called dikaryons, develop into the fruiting bodies known as asci, which are characteristic of the Ascomycetes, the two nuclei fuse inside each ascus (singular of asci). This is the process of fertilization. Then the diploid nucleus undergoes meiosis, forming four haploid nuclei. These undergo mitosis, forming eight haploid nuclei that become the ascospores. When the ascus ruptures, the ascospores are liberated.

Figure 19.1 Yeast cells in various stages of budding.

BASIDIOMYCOTA: CLUB FUNGI

The Basidiomycota, or club fungi, include most of the common mushrooms. Their fruiting bodies are known as mushrooms (see Figure 19.2), basidia, or clubs; they are formed when two hyphae fuse. This is fertilization. A diploid nucleus is formed that undergoes meiosis, forming four haploid nuclei that move along thin extensions created by outgrowths of the cell walls. These nuclei are pushed to the edge of the club, where these basidiospores (spores) easily break off from their delicate stalks and are carried away by the slightest breeze. If they land in a suitable location, the spores germinate and grow hyphae, which form a mycelium that eventually sends up more fruiting bodies (see Figure 19.3).

Figure 19.2 The mushroom known as the common edible morel is a fruiting body of the mass of branching hyphae, called the mycelium, growing underground.

Figure 19.3 Growth of a common poisonous mushroom (Amanita).

IMPERFECT FUNGI

Theimperfect fungi represent about 25,000 fungal species for which sexual reproduction has either been lost or has yet to be observed. Without information about their sexual stages, it has not been possible to identify the characteristic structures that would help specialists classify them appropriately. Accordingly, they have all been lumped together and called imperfect. Members of this group are responsible for ringworm and athlete's foot; both are fungi that infect people without ever sprouting fruiting bodies. (For more, see the Glossary.)

MYCORRHIZAE

Mycorrhizal associations occur when the hyphae of a fungus grow around, between, and sometimes even into living plant root cells. Such associations have been found to occur in at least 90% of all the different plant families. Eighty percent of all the angiosperms (flowering plants) may have such associations. These relationships are symbiotic.

Plants benefit because the mycorrhizae mobilize nutrients by secreting enzymes that help to decompose the litter in the soil. And then, by acting as root hairs, they help to absorb the nutrients, especially nitrogen and phosphorus, by moving these nutrients from the soil into the root tissue. Mycorrhizae also secrete antibiotics that help reduce the plant's susceptibility to infection by pathogens. The mycorrhizae benefit by absorbing the chemicals and carbohydrates that constantly leak through the roots.

Many of the mushrooms seen under trees and shrubs are the fruiting bodies of the fungi that have a mycorrhizal relationship with the roots of the neighboring plants. One often sees certain species of mushrooms associated with certain species of plants because mycorrhizal relationships are quite specific.

LICHENS

Lichens are symbiotic combinations of organisms living together intimately. The species involved are always a fungus and either a chlorophyte (green algae) or a cyanobacteria (blue-green bacteria). The fungi are always either members of Ascomycetes or Basidiomycetes. Although the fungi involved in lichens are usually not found growing alone, the photosynthetic portion of the lichens sometimes does live on its own. It is clear that the fungus living in a lichen benefits from the organic compounds obtained from the photosynthesizing member of the association. The algae may obtain water and minerals from the fungus, but this part of the interaction isn't well understood.

Because lichens are so tolerant of drought, heat, and cold temperatures, they are often the most important autotrophs found on recent lava flows, as well as on the stones used to construct buildings and gravestones. Lichens are also associated with dry, exposed soils, such as those in some deserts, and they also commonly occur in cold, exposed regions.

Most lichens reproduce either by fragmentation, when pieces break off and are blown elsewhere, or by spores produced by the fungal part of the lichen. The spores are blown or washed elsewhere, where they may grow and come in contact with an appropriate algal species. This marks the beginning of another lichen.

KEY TERMS

| asci | imperfect fungi |

| Ascomycota | lichens |

| ascospores | multinuclear |

| basidia | mushrooms |

| Basidiomycota | mycelium |

| basidiospores | mycorrhizal associations |

| club fungi | Oomycota |

| clubs | parasites |

| coenocytic | plasmodium |

| conidia | pseudoplasmodium |

| conidiospores | sac fungi |

| dikaryons | saprophytes |

| flagellated gametes | septa |

| fragmentation | slime molds |

| fruiting bodies | spores |

| Fungi | water molds |

| hyphae | Zygomycota |

SELF-TEST

Multiple-Choice Questions

- Slime molds have a diploid, coenocytic, amoeboid mass that is known as a(n) __________.

- true fungus

- mushroom

- ascus

- plasmodium

- water mold

- Fungi are never __________.

- unicellular

- multicellular

- eukaryotic

- prokaryotic

- heterotrophic

- Fungi __________.

- photosynthesize

- absorb food through their hyphae

- have leaves

- have true roots

- contain chloroplasts

- Together, the mass of branching hyphae creates the body of the fungus, called a __________.

- plasmodium

- mycelium

- coenocyte

- slime mold

- lichen

- Some hyphae are coenocytic, having many nuclei within the cytoplasm, and others are divided by __________ into compartments containing one or more nuclei.

- lichens

- mycelia

- cyanobacteria

- septa

- none of the above

- Slime molds send up __________.

- mushrooms

- spore-bearing fruiting bodies

- seed-bearing structures

- leafy parts

- none of the above

- Many true fungi have mycelia that grow in a close, intimate manner with plant roots, where the plants benefit by receiving __________ and __________ while the fungus benefits by receiving nutritious __________.

- carbohydrates, nitrogen, phosphorus

- nitrogen, carbohydrates, phosphorus

- nitrogen, phosphorus, carbohydrates

- all of the above

- none of the above

- Lichens involve the close association of a __________ and a __________.

- fungus, chlorophyte

- fungus, green algae

- cyanobacteria, fungus

- blue-green bacteria, fungus

- all of the above

- When the hyphae of a fungus grow around, sometimes in between, and even within living plant root cells, the association is __________.

- mycorrhizal

- beneficial to the hyphae

- beneficial to the plant

- all of the above

- none of the above

ANSWERS

- d

- d

- b

- b

- d

- b

- c

- e

- d

Questions to Think About

- Define the shared characteristics of organisms in the kingdom Fungi, and contrast this kingdom with the others.

- List four groups of fungi. Explain their differences and yet the similarities that make them fungi rather than members of another kingdom.

- What are lichens? Are they fungi? Why?

- What are mycorrhizal associations? Who benefits from them? How and why?

- Are all fungi always multicellular? If not, when aren't they? Give specific examples.

- What part does a mushroom play in the life history of which fungi?

- Athlete's foot is caused by a fungus, yet one never sees any fruiting bodies. Why?