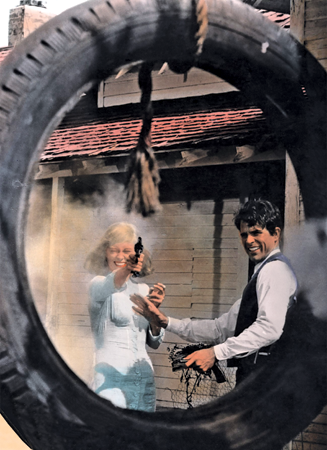

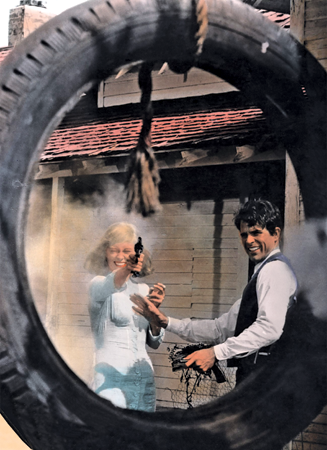

1967

Bonnie and Clyde

DIR. ARTHUR PENN

EVERETT

The terrible twosome (Faye Dunaway and Warren Beatty) use a tire for target practice.

Just before dawn on May 23, 1934, the notorious criminal Clyde Barrow and his companion, Bonnie Parker, were ambushed and shot to death by police officers while driving a stolen car near Sailes, Louisiana. It was the suitably dramatic end to an extended crime spree: For nearly two years, the couple had roamed Texas and Oklahoma, committing 13 murders and multiple robberies. In the process, they gained notoriety as a Depression-era Robin Hood and his murderous Maid Marian.

Their lurid legend was further burnished with the groundbreaking Bonnie and Clyde, starring Warren Beatty and Faye Dunaway. Anticipating other genre reinventions that later fueled the comparatively toothless Raiders of the Lost Ark and Star Wars, Bonnie and Clyde was a contemporary spin on ’30s gangster movies. To this bad-boy bedrock the filmmakers added the influence of the French new wave, exemplified by the work of François Truffaut and Jean-Luc Godard, both of whom had been approached to direct.

Prefiguring the work of Quentin Tarantino by 25 years, the film mixed farce and eroticism with unprecedented violence—particularly in the final ambush, in which Clyde and Bonnie are riddled with bullets in a scene that left nothing to the imagination. Partly as a result, the film’s studio, Warner Bros., was leery of the film—as were many critics. (The New York Times damned it as both “strangely antique, sentimental claptrap” and “reddened with blotches of violence of the most grisly sort.”)

But audiences embraced the antiheroic antics. Released at a time marked by both the acid-soaked utopian Summer of Love and mass protests against the Vietnam War, the film became a counterculture touchstone. Just as the murderous couple had become Depression-era folk heroes, so their cinematic counterparts spoke to the youth of the antiauthoritarian 1960s. In the film, for instance, Bonnie reads a poem: “If a policeman is killed in Dallas / and they have no clue to guide / if they can’t find a fiend / they just wipe their slate clean / and hang it on Bonnie and Clyde.”

JERRY TAVIN/EVERETT

Beatty didn’t direct Bonnie and Clyde, but he belied his pretty-boy status by exerting a committed, visionary, and almost obsessive control on the set. “It is all detail, detail, detail,” he once said. “That’s where the stamina comes in.” The relentless lothario showed plenty of stamina offscreen, too.

© WARNER BROS., COURTESY PHOTOFEST

Buck Barrow, Clyde Barrow, and Bonnie Parker (Gene Hackman, Beatty, and Dunaway), having just made a withdrawal at the bank. In actuality, Bonnie and Clyde robbed relatively few banks, stealing instead from gas stations and grocery stores, their haul often only five or 10 bucks.

EVERETT

Dunaway and Beatty are the height of criminal chic. The real-life Bonnie and Clyde were far less photogenic, but they did pose for photos that went public.