1974

Chinatown

DIR. ROMAN POLANSKI

PARAMOUNT/KOBAL/ART RESOURCE, NY

Faye Dunaway (as Evelyn Mulwray) tends to the slashed schnoz of Jack Nicholson (J.J. Gittes) while contemplating, it seems, more intimate ministrations.

If Truman Capote hadn’t penned a disastrous screenplay for The Great Gatsby in the early ’70s, Chinatown might never have been made. Trying to salvage the project, producer Robert Evans asked script doctor Robert Towne to rewrite the screenplay. But Towne didn’t relish the idea of taking on F. Scott Fitzgerald. Instead, he told Evans about a film that he was writing for Jack Nicholson. It was, Towne said, the story of “how L.A. became a boomtown: incest and water.”

Towne meant the so-called rape of the Owens Valley, from which water was diverted to the dry Los Angeles desert by means of an aqueduct the city constructed in the early 1900s. Directed by Roman Polanski, Chinatown uses this historical event to fuel a labyrinthine plot that can’t be effectively summarized here. So let’s just say that it begins in 1937 Los Angeles when a mystery woman (Diane Ladd) asks J.J. Gittes (Nicholson), a sleazy detective straight out of pulp noir, to spy on her husband. Naturally, she thinks he’s cheating on her. The visit leads Gittes into a web of deception, perversion, and the mystery surrounding Los Angeles’s water supply.

In the hands of Polanski, the film took on a far darker cast than Towne had intended. The director wanted Chinatown to be “special, not just another thriller where the good guys triumph in the final reel.”

The sinister sensibility the director brought to nearly all his films was nothing if not personal. A Holocaust survivor, he had endured the murder of his pregnant wife, Sharon Tate, at the hands of the Manson family just a few years before. And his personal life remained controversial. In 1977, he was arrested for drugging and raping a 13-year-old girl in Nicholson’s hot tub, and he fled the U.S. before final sentencing.

Chinatown celebrated its 40th anniversary in 2014, yet it probably would not be made in contemporary Hollywood, according to Towne. In the ’70s, “a series of shared beliefs . . . focusing on what was wrong with the country, created a sense of communion between filmmakers and filmgoers,” he wrote. “We share no such beliefs today . . . It’s difficult to lie credibly without belief in the truth.” Chinatown remains the most iconic neo noir ever and the one that reintroduced the genre to modern audiences. “It’s film noir as the Great American Movie,” novelist Jake Hinkson tells LIFE. “It really doesn’t get any better—any darker, any truer, any sadder—than this.”

© PARAMOUNT PICTURES, COURTESY PHOTOFEST

Gittes offers Evelyn an immodest proposal.

© PARAMOUNT PICTURES, COURTESY PHOTOFEST

Evelyn is up in arms.

EVERETT

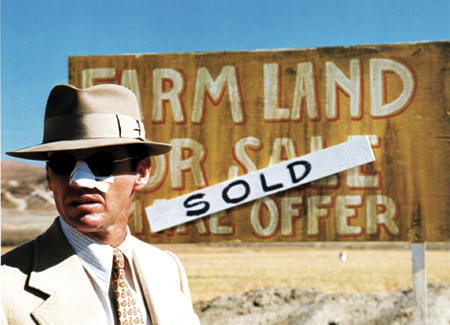

Gittes in front of the sign that reflects Chinatown’s shady water politics, based on what was known as the rape of the Owens Valley and motivated, of course, by greed. At one point, addressing John Huston as millionaire Noah Cross, Gittes asks, “How much better can you eat? What can you buy that you can’t already afford?” Cross’s reply: “The future.” Diverting the water from the valley did turn Los Angeles from a desert to a boomtown, but nature always wins in the end: The City of Angels faces an enduring drought.